Abstract

The clinical phenotype in osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is attributed to the dominant negative function of mutant type I collagen molecules in the extracellular matrix, by altering its structure and function. Intracellular retention of mutant collagen has also been reported, but its effect on cellular homeostasis is less characterized. Using OI patient fibroblasts carrying mutations in the α1(I) and α2(I) chains we demonstrate that retained collagen molecules are responsible for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) enlargement and activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) mainly through the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 3 (PERK) branch. Cells carrying α1(I) mutations upregulate autophagy, while cells with α2(I) mutations only occasionally activate the autodegradative response. Despite the autophagy activation to face stress conditions, apoptosis occurs in all mutant fibroblasts. To reduce cellular stress, mutant fibroblasts were treated with the FDA-approved chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyric acid. The drug rescues cell death by modulating UPR activation thanks to both its chaperone and histone deacetylase inhibitor abilities. As chaperone it increases general cellular protein secretion in all patients' cells as well as collagen secretion in cells with the most C-terminal mutation. As histone deacetylase inhibitor it enhances the expression of the autophagic gene Atg5 with a consequent stimulation of autophagy. These results demonstrate that the cellular response to ER stress can be a relevant target to ameliorate OI cell homeostasis.

Keywords: Collagen, Osteogenesis imperfecta, Autophagy, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, Chemical chaperone, Unfolded protein response

Highlights

-

•

Retained mutant collagen activates the Unfolded Protein Response pathway.

-

•

Autophagy is consistently upregulated in fibroblasts carrying α1(I) mutations.

-

•

Autophagy is sometimes upregulated in fibroblasts carrying α2(I) mutations.

-

•

Apoptosis occurs in all mutant fibroblasts carrying type I collagen mutations

-

•

4-PBA rescues cell death by modulating UPR activation and activating autophagy.

1. Introduction

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is one of the more common of the rare hereditary skeletal dysplasias, with an incidence of 1:15–20,000 [1]. The OI phenotype, ranging from very mild osteoporosis to perinatal lethality, is characterized by reduced bone mineral density, deformed bones and frequent fractures in the absence of or in response to minor trauma [2]. Classical OI (types I to IV, based on Sillence classification) is a dominantly inherited bone dysplasia caused by mutations in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes, encoding for α1 and α2 chains of type I collagen, respectively [3]. Type I collagen is the most abundant protein of skin and bone extracellular matrix (ECM). The delay in type I collagen folding due to glycine substitution in the procollagen chains is responsible for a prolonged exposure of the chains to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) enzymes responsible for post-translational modifications [1]. Thus, in OI cells trimeric collagen molecules are synthesized with increased proline and lysine hydroxylation and hydroxylysine glycosylation [4]. The overmodification is broadly dependent on the position of the mutation along the chains. Since collagen folds in a zipper like fashion, from the C- to the N-terminal end, it was previously thought that this contributed to the severity of the phenotype of mutations at the C- terminus of the α1(I) chain. Now this outcome is understood to be influenced by the major ligand-binding region (MLBR) near the C-terminus as well as by the particular substituting amino acid [5,6]. The overmodification remains useful as a measure of delayed folding of helices containing mutant chains.

The mutated type I collagen is predominantly secreted in the ECM, but partially retained intracellularly [2]. While the detrimental effect of its presence in the ECM has been widely investigated and considered the major cause of the OI bone phenotype, its intracellular role is less well understood [2]. An accumulation of mutant collagen in the ER was detected alongside a 40% matrix insufficiency in the Brtl murine model for classical OI, carrying a heterozygous α1(I)-G349C substitution [7]. Similarly, ER enlargement was described in the dominant OI murine model Amish, carrying an α2(I)-G610C substitution and in the heterozygous Aga2 OI murine model carrying a C-terminal single nucleotide deletion responsible for a frameshift changing the last 90 amino acids of the proα1(I) [[8], [9], [10]]. Enlargement of the ER cisternae was also detected in recessive OI caused by mutations in the collagen specific chaperones FK506 binding protein 10 (FKBP10) and SERPINH1 known to be involved in collagen folding and secretion [11,12].

Ishida et al. demonstrated that monomeric proα chains are degraded by the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway, whereas procollagen aggregates, caused by the presence of C-propeptide or triple helical mutations, not impairing trimeric collagen assembly, are eliminated by autophagy [13]. Similarly, Miringian et al. observed the autophagic, but not the proteosomal degradation of mutant collagen in primary osteoblasts obtained from the Amish OI murine model [9].

The type and regulation of the cellular response to the intracellular accumulation of mutant collagen is still an open question. The unfolded protein response (UPR), an evolutionary conserved adaptive response, is generally activated to maintain the functional integrity of the ER under stress conditions (14). The UPR consists of three major signaling cascades initiated by three ER-resident proteins: ER to nucleus signaling 1 (ERN1/Ire1α), activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha kinase 3 (PERK) [14].

Earlier studies by Chessler and Lamande using fibroblasts obtained from OI patients revealed that the retained abnormal collagen is interacting with the UPR sensor BIP, pointing to the activation of the unfolded protein response [15,16]. However, BIP interaction was demonstrated only in the presence of C-propeptide mutations and not in the presence of triple helical glycine substitutions, suggesting in the latter case the activation of an as yet undefined UPR pathway [17].

When ER stress persists and the UPR fails to restore normal cell homeostasis, programmed cell death may occurs [18]. In this contest, the response to ER stress becomes an important modifier of disease severity [17]. Indeed, chemical chaperones, molecules able to help protein folding, had been proposed and used in preclinical and clinical trials to treat diseases caused by intracellular accumulation of misfolded proteins [19]. Among the chemical chaperones already approved by the FDA, although for a different indication, 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) is appealing to treat collagen-related disorders associated with ER stress [20]. Indeed 4-PBA has been successfully used for rescue the cellular phenotype of hemorrhagic stroke due to intracellular mutant collagen type IV [21]. In the OI context, we recently demonstrated a skeletal amelioration in the Chihuahua zebrafish model of classical OI following 4-PBA treatment [22].

The aim of the present study was to elucidate the effect of the intracellular retention of mutant collagen on cellular functions and to investigate whether this condition could be a valid target to rescue OI cellular homeostasis. OI patients’ fibroblasts were chosen for the analyses since they are more accessible than osteoblasts and produce a high level of type I collagen. Although OI affects mainly bone tissue, skin abnormalities were reported in patients using skin quantitative magnetic resonance microimaging and histological analysis [23,24]. Moreover similar altered pathways were identified in bone and skin in the Brtl mouse, and the same alterations were also detected in primary OI fibroblasts [[25], [26], [27]]. For our studies we selected fibroblasts from patients who carry glycine substitutions by various amino acids in different locations along the α1(I) or α2(I) chains (Table 1). Of note, two cell lines obtained from independent patients carrying an identical glycine substitution (G667R), but causing lethal (OI type II) or non-lethal (OI type III) outcome, respectively, were also available.

Table 1.

Patients fibroblasts used in the study.

| Glycine substitutiona | Genetic mutation | Protein mutationb | OI typec | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1(I) | G226S | c.1210G>A | p.G404S | III | 6 | |

| G478S | c.1966G>A | p.G656S | II | 28 | ||

| G667R | c.2533G>A | p.G845R | III | Marini p.c. | ||

| G667R | c.2533G>A | p.G845R | II | Marini p.c. | ||

| G994D | c.3515G>A | p.G1172D | II | 28 | ||

| α2(I) | G319 V | c.1226-7GA>TT | p.G409 V | II | 28 | |

| G640C | c.2188G>T | p.G730C | II/III | 29 | ||

| G697C | c.2359G>T | p.G787C | II | 28 | ||

| G745C | c.2503G>T | p.G835C | III | 30 | ||

| G859S | c.2845G>A | p.G949S | III | 6 |

p.c. personal communication

position of mutated glycine into the collagen helix considering the initial gly of the triple helix as amino acid 1.

amino acid number considering the initial methionine codon as amino acid 1.

OI type based on Sillence's classification.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Human fibroblasts

Human fibroblasts from skin biopsy of OI patients, carrying mutations in COL1A1 (n = 5) or in COL1A2 (n = 5) genes, and three age matched controls were obtained after informed consent and used up to passage P10 (Table 1) [6,[28], [29], [30]]. Cells were grown at 37 °C in humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and cultured in Dulbecco Modified Eagle's Medium (D-MEM) (4.5 g/l glucose) (Lonza) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Euroclone), 4 mM glutamine (Euroclone), 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin (Euroclone). For each experiment, except where differently stated, 2.5 × 104 cells/cm2 were plated and harvested after 5 days with no media change. For drug treatment cells were incubated for 15 h with 5 mM 4-PBA (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysosome was blocked using 10 μM chloroquine (Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 h.

2.2. Steady state and chase collagen analysis

Labelling of collagen with L-[2,3,4,5-3H]-proline (PerkinElmer) was used to evaluate collagen over-modification. 2.5 × 104 fibroblasts/cm2 were plated into 6-wells-plate and grown for 24 h. Cells were then incubated for 2 h with serum-free D-MEM containing 4 mM glutamine, 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin and 100 μg/ml (+)‑sodium l-ascorbate (Sigma-Aldrich) to stimulate collagen production. For steady state experiments the labelling was performed for 18 h in the same media using 28.57 μCi of 3H-Pro/ml. For chase experiments the labeling was performed for 4 h using 47.14 μCi of 3H-Pro/ml, then the labeling media was replaced with serum-free D-MEM containing 2 mM proline (Sigma-Aldrich), 4 mM glutamine, 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin and 100 μg/ml (+)‑sodium l-ascorbate (chase media). Collagen was collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 3 and 4 h after the pulse. Collagen extraction was performed as previously reported [31]. Briefly, medium and cell lysate fractions were digested o/n with 100 ng/ml of pepsin in 0.5 M acetic acid at 4 °C. Collagen was then precipitated using 2 M NaCl, 0.5 M acetic acid. Collagen was resuspended in Laemmli buffer (62 mM Tris HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate, 0.02% bromophenol blue) and the radioactivity (counts for minute, CPM) was measured using a liquid scintillation analyzer (PerkinElmer TRI-CARB 2300 TR).

For steady state analyses equal amounts of 3H-labeled collagen from each patient cells were loaded on 6% urea-SDS gel in non-reducing condition. For chase analyses the same volume of 3H-labeled collagens from each time point was electrophoresed. The gels were fixed in 45% methanol, 9% glacial acetic acid, incubated for 1 h with enhancer (PerkinElmer, 6NE9701), washed in deionized water, and dried. 3H gel radiographs were obtained by direct exposure of dried gels to hyperfilm (Amersham) at −80 °C. The radiographs were acquired by VersaDoc 3000 (BioRad) and α1 band intensity was evaluated by Quantity One software (BioRad). For chase analyses the ratio between the collagen in the media and the total collagen (medium plus cell layer collagen) was evaluated by measuring the density of the α1(I) band to quantify the percentage of collagen secretion. Each chase experiment was run at least in duplicate.

2.3. Transmission electron microscopy analysis

For transmission electron microscopy analysis, fibroblasts from controls and patients were trypsinized and centrifuged at 1000g for 3 min. The pellet was fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in the culture medium for 2 h at room temperature. The cells were rinsed in PBS and then in H2O. Finally, the fibroblasts were fixed in 2% (w/v) OsO4 in H2O for 2 h at room temperature (RT), rinsed in distilled water and embedded in 2% agarose in H2O. The specimens were then dehydrated in acetone and finally infiltrated with Epoxy resin overnight (o/n), and polymerized in gelatin capsules at 60 °C for 24 h. Thin sections (60–70 nm thick) were cut on a Reichert OM-U3 ultramicrotome with a diamond knife and collected on 300-mesh nickel grids. The grids were stained with saturated aqueous uranyl acetate by lead citrate and observed with a Zeiss EM900 electron microscope, operated at 80 kV with objective aperture of 30 μm.

2.4. Protein lysates

Fibroblasts were washed with PBS, scraped in PBS, centrifuged at 1000g for 4 min and lysed and sonicated in RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% IGEPAL® CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris, pH 8) supplemented with protease inhibitors (13 mM benzamidine, 2 mM N-ethylmalemide, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 2 mM NaVO3). Proteins were quantified by RC DC Protein Assay (BioRad). Bovine Serum Albumine (BSA) (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as standard.

2.5. Western blot

Proteins from human fibroblasts lysates (10–50 μg) were separated on SDS-PAGE with the acrylamide percentage ranging from 6% to 15% depending on the size of the analyzed protein. The proteins were electrotransferred from the gel to a PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare) at 100 V for 2 h on ice in 19 mM Tris HCl, 192 mM glycine and 20% (v/v) methanol. The membranes were then blocked with 5% (w/v) BSA in 20 mM TrisHCl, 500 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (TBS), 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) (TBS-T) at RT for 1 h. After washing with TBS-T the membranes were incubated with 1:1000 primary antibody against the specific protein BIP (Cell Signaling), IRE1α (Cell Signaling), PERK (Cell Signaling), PDI (Cell Signaling), p-PERK (Thr980) (Cell Signaling); LC3A/B (Cell Signaling), ATG5 (Cell Signaling), ATG12 (Cell Signaling) and ATG16L1 (Cell Signaling); Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling), Cleaved Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling); ATF4 (Novus Biological); p-IRE1α (Ser724) (Novus Biological), ATF6 (Abcam); acetyl hystone H3J (ThermoFisher); in 5% BSA in TBS-T o/n at 4 °C. The appropriate secondary antibody anti-mouse (Cell Signaling), anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling) or anti-goat (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), was added at dilution of 1:2000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T for 1 h at RT. Anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1:1000 in 5% BSA in TBS-T was used for protein loading normalization. The signal was detected by ECL Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare) and images were acquired with ImageQuant LAS 4000 (GE Healthcare), using the ImageQuant LAS 4000 1.2 software. Bands intensity was evaluated by densitometry, using ImageQuant TL analysis software. For each gel, the intensity of the control band was set equal to one and the expression of the mutant samples was expressed as fold difference. For each cell line, three independent lysates were collected and technical triplicates were performed.

2.6. LC3 immunofluorescence

1.5 × 104 fibroblasts were plated on sterile glass coverslips (Marienfeld) in 24 well plate in triplicate. After 5 days, cells were treated for 6 h with 10 μM chloroquine. After the treatment, the medium was removed and cells were fixed with cold 100% CH₃OH for 15 min at −20 °C, washed 3 times with PBS and blocked 1 h in 1% BSA in PBS containing 0.3% TritonX100. Then, cells were incubated with LC3 primary antibody (Cell Signaling) diluted 1:500 in 1% BSA, 0.3% TritonX100 in PBS o/n at 4 °C. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated with secondary antibody (AlexaFluor 488 coniugated F(ab’) fragment anti- rabbit IgG, Immunological Sciences) diluted 1:2000 in 1% BSA, 0.3% Tritonx100 in PBS for 2 h at RT. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich). The samples were analyzed by TCS SP2- Leica confocal microscope (Leica). The total area of punctate signal per cell was measured by the Leica software LAS4.5.

2.7. Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)

To analyze apoptosis the FACS Annexin V/Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (Invitrogen) was used following manufacturer instruction. As positive control for the activation of apoptosis cells were treated with 20 μM thapsigargin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h in serum-free D-MEM. Samples were analyzed by Cell Sorter S3 (Biorad), 1 × 104 events for each sample, measuring the fluorescence emission at 510–540 nm and >565 nm.

2.8. Protein secretion

OI patients' fibroblasts were plated in 24 well plate and after 5 days without changing the medium were labeled with 5 uCi/ml [35S] EXPRESS35S Protein Labeling Mix (PerkinElmer) in D-MEM without l-methionine, l-cystine, and l-glutamine for 1 h at 37 °C. Total proteins from medium and cell layer were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. Proteins were washed with acetone twice and resuspended in 60 mM Tris HCl, pH 6.8, 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate. The radioactivity (counts for minute, CPM) of the samples was measured using a liquid scintillation analyzer (TRI-CARB 2300 TR). The percentage of protein secretion was calculated based on the ratio between the CPM in the media and the CPM in medium and cell layer, evaluated in 5 technical replicates.

2.9. Expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from patients fibroblasts using TriReagent (Sigma–Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's protocol. DNase digestion was performed using the Turbo DNA Free Kit (Ambion, Applied Biosystems), and RNA integrity was verified on agarose gel. cDNA was synthetized and qPCR was performed on the Mx3000P Stratagene thermocycler using commercially available TaqMan primers and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). All reactions were performed in triplicate. Expression level for ATG5 (ThermoFisher, Hs00169468_m1) was evaluated. GAPDH (ThermoFisher, Hs99999905_m1) and ACTB (ThermoFisher, HS99999903) were used as normalizer. Relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

2.10. XBP1 splicing analyses

cDNA from control and patients cells was used as a template for PCR amplification across the region of the XBP1 cDNA (NM_005080.3) containing the intronic target of IRE1α ribonuclease using 0.3 μM sense (nt 396-425; 5′-TCA GCT TTT ACG AGA GAA AAC TCA TGG CCT-3′) and antisense primers (nt 696-667; 5′-AGA ACA TGA CTG GGT CCA AGT TGT CCA GAA-3′). Following a 30 min incubation at 50 °C, reactions were cycled 30 times at 94 °C, 60 °C and 72 °C for 30 s at each temperature. Reaction products were electrophoresed on 7% TBE acrylamide gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

2.11. Statistic analysis

Statistic differences between patients and controls were evaluated by two-tailed Student's test. Technical triplicates were performed, except when otherwise specified, and values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Mutant overmodified type I collagen causes ER cisternae enlargement

Electrophoretic analysis of 3H-proline labeled type I collagen obtained from patient and control primary fibroblasts was used to demonstrate increased glycosylation level associated with glycine substitutions (Fig. 1A). Steady-state collagen gels revealed the typical delayed broader and/or double α(I) bands in both media and cell lysates obtained from cells carrying the α1-G478S, α1-G667RII, α1-G667RIII, α1-G994D, α2-G319 V, α2-G745C, α2-G640C and α2-G697C mutations. In agreement with the collagen folding direction, from C- to N-terminus, only the cells carrying an N-terminal mutation, the α1-G226S, produced normal migrating collagen chains (Fig. 1A). The exception to the C-/N-terminal rule is represented by α2-G859S fibroblasts where normal migrating α bands were detected, likely given the proximity of the mutated residue to a highly flexible region more permissive for folding [32].

Fig. 1.

Mutations in type I collagen genes lead to collagen overmodifications and ER enlargement. (A) Electrophoretic analyses of type I collagen extracted from patients' fibroblasts with dominant OI. Fibroblasts were labeled with 3H-Proline for 18 h. Type I collagen was extracted from cell layer (upper panel) and medium (lower panel) fractions and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Representative radiographs are shown. A typical broadening or doubling of the α(I) bands in both fractions is observed in all cells except the very N-terminal mutation α1-G226S and the α2-G859S. (B) Transmission electron microscopy analysis of OI fibroblasts revealed the presence of ER enlargement (*) and of cellular vacuolization (arrow). N = nucleus. Magnification 20,000×.

Electron microscopy imaging performed on cells representative for α1 and α2 mutations revealed ER dilatation and the presence of large vacuoles, resembling autophagosome vesicles, since double membrane and presence of residual material were occasionally detectable (Fig. 1B).

3.2. Retained mutant procollagen activates the unfolded protein response

Expression of chaperones and proteins involved in the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway was evaluated (Supplementary Table 1). The expression of BIP, the best characterized activator of the UPR sensors, was increased in 3 out of 5 cells carrying mutations in the collagen I α1 chain and in 3 out of 5 cells with mutations in the collagen I α2 chain (Fig. 2A-B). Interestingly, upregulation of BIP was detected in α1-G667RII associated with a lethal phenotype, while its expression was normal in α1-G667RIII cells from a patient with a moderate severe phenotype (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Mutations in type I collagen genes activates the unfolded protein response in OI patients' fibroblasts. Western blot analyses of the collagen chaperone PDI and of proteins involved in the UPR (BIP, PERK, p-PERK, ATF4, ATF6, IRE1α and p-IRE1α) in cells with mutations in the α1 (A) and α2 chains (B). UPR resulted activated in all patients fibroblasts except in α2-G640C. (C) RT-PCR amplification of XBP1 mRNA from control and patients cells. The spliced XBP1-1s form of XBP1 transcript is found in patients cells with α1-G667RIII, α1-G994D, α2-G319V,α2-G697C, α2-G745C and α2-G859S mutations. Complete splicing is detected in control fibroblasts treated with thapsigargin (Thap). OI type II: lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. OI type III: non-lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. C-: negative control. * p < 0.05.

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), which catalyzes the formation and isomerization of disulfide bonds and it is known to interact with single collagen α chains, was upregulated in all α1(I) mutated cells, with the exception of the α1-G667RII (Fig. 2A). By contrast, in the α2(I) mutated cells PDI expression was unchanged (Fig. 2B).

The activation of the UPR sensors PERK and IRE1α by phosphorylation and of ATF6 by proteolytic cleavage was then investigated. p-PERK/PERK ratio was increased in all mutant fibroblasts with α1(I) and α2(I) mutations independently from the location/type of the mutation, with the exception of α2-G640C (Fig. 2A–B). Consistently, the expression of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), the effector in the PERK pathway, was increased with the exception of the most N-terminal α1-G226S line (Fig. 2A–B).

The IRE1α branch was activated in the α1(I) mutated cells α1-G667RIII and α1-G994D and in all cells with mutations in α2, with the exception of α2-G640C, as demonstrated by the level of p-IRE1αI and by the IRE1α- mediated splicing of XBP1 (Fig. 2A, B, C).

No difference in the level of cleaved ATF6 was detectable in any cells (Fig. 2A-B).

Based on our data, mutant collagen synthesis and intracellular retention cause disruptions of ER homeostasis and determine the activation of the unfolded protein response in OI fibroblasts with mutations in both the α1 and α2 chains. The α2-G640C cells represent the only exception to this rule being characterized by the presence of overmodified collagen without UPR activation.

3.3. OI fibroblasts react to cellular stress by upregulating autophagy

Since autophagy is the first cell response to dysfunctional cellular components [[33], [34], [35]], its activation in OI fibroblasts, consequent to the presence and/or intracellular accumulation of mutated collagen, was evaluated. By Western blotting experiments we observed that the expression level of ATG5-12 complex, necessary for autophagosome elongation, was significantly increased in the cell lines α1-G226S, α1-G667RII and α1-G667RIII and the expression of ATG16, which together with ATG5-12 promotes elongation and closures of the autophagosome, was increased in all cells with mutations in α1(I), whereas no upregulation was detected in α2(I) cells (Fig. 3A-B). However, the levels of ATG5-12 and ATG16 are not always correlated to autophagy activation [36]. The terminal fusion of an autophagosome with its target membrane involves LC3-I processing to LC3-II due to the conjugation with phosphatidylethanolamine. The measurements of static and dynamic LC3IIA/B levels in the absence/presence of chloroquine were performed to monitor autophagy (Fig. 3). In static conditions the expression of LC3-II was upregulated in α1-G226S, α1-G478S and α1-G667RII cells (Fig. 3A) while following chloroquine treatment the level of LC3-II increased in all the α1 mutated lines indicating a general accumulation of LC3 due to the block in autophagic flux (Fig. 3C). In α2(I) fibroblasts a LC3-II accumulation was detected in untreated α2-G319V, α2-G697C and α2-G859S (Fig. 3B) and confirmed under dynamic conditions for α2-G697C and α2-G859S (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

OI cells react to cellular stress by activating autophagy. (A–B) Western blot analyses of proteins involved in the autophagic pathway (ATG5-12, ATG16L1, LC3-I/LC3-II) in OI fibroblasts with mutations in COL1A1 (A) and COL1A2 (B) genes. Protein components involved in the formation of the autophagosome are upregulated in patients with α1(I) mutations. The terminal autophagic marker LC3 is upregulated in the majority of cases. (C-D) LC3 Western blot analyses in the presence of chloroquine in OI fibroblasts with mutations in COL1A1 (C) and COL1A2 (D) genes. The terminal marker of autophagy evaluated in dynamic conditions is increased in all patients’ cells except in α2-G640C and α2-G745C. OI type II: lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. OI type III: non-lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. * p < 0.05.

To independently validate the activation of the autophagic pathway, LC3 immunofluorescence was analyzed in OI fibroblasts in the presence of chloroquine. The LC3 signal was significantly increased compared to controls in α1-G478S, α1-G667RIII, α1-G667RII, α1-G994D, α2-G697C, and α2-G859S cells while it remained unchanged in α2-G640C (Fig. 4), in agreement with the Western blot data.

Fig. 4.

Autophagy activation in OI cells. Autophagy was evaluated in control and OI fibroblasts α1-G478S, α1-G667RIII, α1-G667RII, α1-G994D, α2-G640C, α2-G697C and α2-G859S by LC3 immunofluorescence in the presence of chloroquine. Representative confocal images of WT and mutant fibroblasts incubated with LC3 antibody are shown. Quantitation of the total area of punctate signal per cell confirms the activation of autophagy. DAPI (nuclei) in blue and LC3 in green. Magnification 40×, zoom 4×. OI type II: lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. OI type III: non-lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. * p < 0.05.

3.4. Cellular stress causes activation of apoptosis

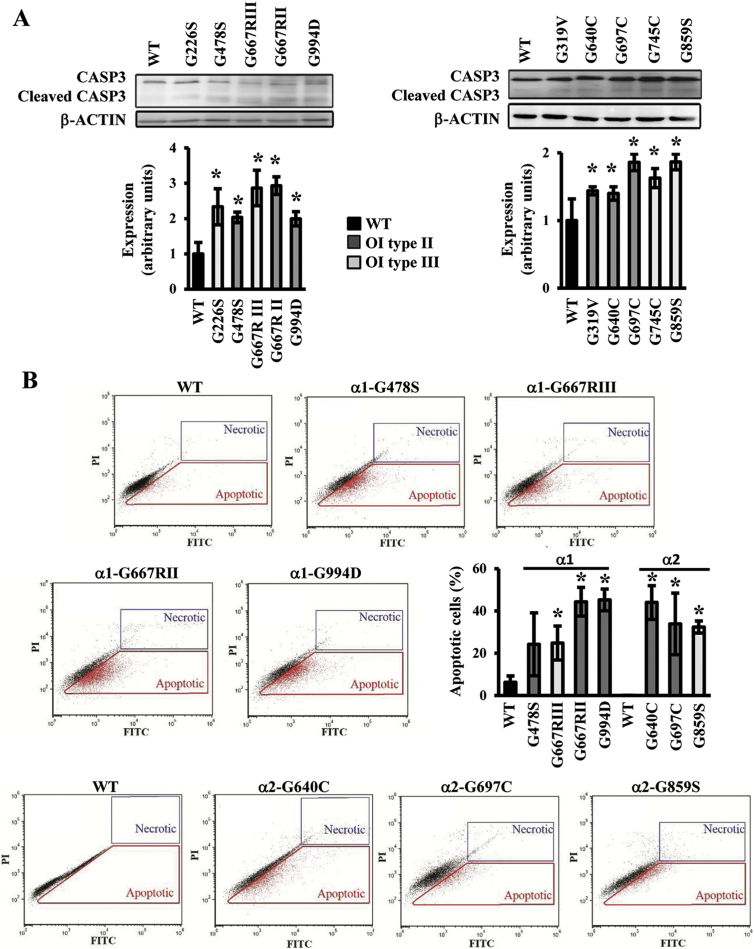

Given that the persistence of ER stress could activate apoptosis as an extreme cellular response to stress, we investigated the level of cleaved caspase 3 showing in all OI mutant cells an increased level of this executioner protease, indicative of apoptosis occurrence (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Activation of apoptosis in OI patients cells. (A) Western blot analyses of the terminal marker of apoptosis cleaved caspase 3. (B) FACS analysis detection of apoptotic cells by concurrent staining with annexin V (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI). The fraction of apoptotic events in the cells is shown in representative plots and quantified in the histogram as mean ± SEM. Apoptosis is activated in all tested OI patients cells. OI type II: lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. OI type III: non-lethal osteogenesis imperfecta. * p < 0.05.

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) of annexin V/dead positive cells confirmed the activation of apoptosis in the OI fibroblasts. A higher percentage of apoptotic cells compared to controls was detected in α1-G478S (p = 0.269), α1-G667RIII (p = 0.046), α1-G667RII (p = 0.004), α1-G994D (p = 0.002) and α2-G640C (p = 0.032), α2-G697C (p = 0.046) and α2-G859S (p = 0.008) (Fig. 5B).

3.5. The chemical chaperone 4-PBA ameliorates OI fibroblasts homeostasis

To evaluate if the alleviation of the stress could ameliorate OI patient cells homeostasis, controls and patients fibroblasts were treated with 4-PBA, a well-known chemical chaperone that is FDA-approved as ammonia scavenger for urea cycle disorders [37]. The effect of the drug was evaluated by Western blotting measuring the expression p-PERK, as marker for UPR, and the activation of caspase 3, as signature for apoptosis. The levels of these markers were compared in treated versus untreated cells and in treated OI cells versus untreated controls. None of the selected markers were significantly changed in WT cells after 4-PBA treatment (Supplementary Table 2).

4-PBA treatment decreased the p-PERK/PERK level in 4 out of 5 cell lines with mutations in α1 chain, reaching values comparable to controls in α1-G667RIII and in α1-G994D (Fig. 6A). A normalization of the PERK activation did not occur in the α1-G667RII (Fig. 6A). Regarding cells with mutations in the α2 chain, 4-PBA decreased the level of p-PERK/PERK to controls value in α2-G697C and α2-G745C (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

4-PBA ameliorates OI fibroblasts homeostasis. To alleviate the stress and to ameliorate OI patients' cells homeostasis, fibroblasts with mutations in COL1A1 (A) and COL1A2 (B) genes were treated with 5 mM 4-PBA for 15 h. The effect of the drug was evaluated following by Western blotting the expression of p-PERK, as markers for UPR, and the expression of cleaved caspase 3, as signature for apoptosis. The levels of these proteins were compared in treated versus untreated cells and in treated OI cells versus untreated controls. 4-PBA treatment mainly restores control values for what concern the activation of the UPR sensor PERK and the activation of the terminal caspase 3 in cells with mutations in the α1 collagen chain. The treatment on α2 mutated cells was effective on α2-G697C and α2-G745C. * p < 0,05 mutant fibroblasts respect to control fibroblasts. # p < 0,05 treated fibroblasts respect to untreated mutant fibroblasts. § p < 0,05 treated fibroblasts respect to untreated control fibroblasts.

Interestingly, the level of cleaved caspase 3 was decreased with respect to untreated cells reaching normal levels in all treated α1 cells, with the exception of the very N-terminal one α1-G226S (Fig. 6A), and in α2-G640C and α2-G859S (Fig. 6B).

Thus, 4-PBA treatment generally restored control values for pPERK/PERK and of the terminal caspase 3 in most of the cells with mutations in the α1 collagen chain. The treatment of α2 mutated cells was effective for these parameters in α2-G697C and α2-G745C.

3.6. 4-PBA stimulates protein secretion and autophagy

In order to understand the molecular basis of the positive 4-PBA action on mutant cellular homeostasis we investigated in our system the chaperone and histone deacetylase inhibitory activity of the drug.

Upon 4-PBA administration protein secretion was increased in all OI cells (Fig. 7A), compared to severely reduced secretion in basal condition (with the exception of the α1-G640C), as evaluated by protein labeling with 35S-l-methionine and 35S-l-cysteine.

Fig. 7.

4-PBA ameliorates OI fibroblasts homeostasis by stimulating protein secretion. (A) After 4-PBA treatment OI patients' fibroblasts were labeled with [35S] EXPRESS35S Protein Labeling Mix for 1 h and total proteins were extracted from medium and cell layer. Determination of the total counts incorporated in cell layer and medium revealed that 4-PBA increases protein secretion in all cells lines. (B) Collagen secretion was evaluated by incubating the cells for 4 h with 47.14 μCi of 3H-Pro/ml, and extracting the collagen from both medium and cell layer fractions at the indicated time points. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE and the ratio between the densitometric value of collagen α1(I) in the media and the total collagen α1(I) (collagen present in medium and in cell layer) was evaluated and shown in the plot. Collagen secretion is delayed in all mutant cells tested compared to controls. Collagen intracellular retention was significant in α1-G994D cells. 4-PBA increased collagen secretion in α1-G994D cells.

To analyze specifically type I collagen secretion, chase experiments with 3H-Pro metabolic labeling were performed and delayed secretion of collagen in all the analyzed OI fibroblasts was shown (Fig. 7B). 4-PBA treatment was able to clearly enhance collagen secretion in the α1-G994D fibroblasts, the cells with the most C-terminal mutation and the one with the strongest intracellular retention.

Since epigenetic modifications play a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression to maintain cell homeostasis [38], and since 4-PBA has a known effect on histone modifications [39], histone H3 acetylation was investigated. 4-PBA increased the level of the H3 modification in all control and mutant cells with the exception of the α1-G478S (Fig. 8A). This increase was associated with the upregulation of the expression of the autophagic gene ATG5 with the only exception of α1-G478S, as shown by qPCR data (Fig. 8B, Supplementary Fig. 1). Importantly mRNA data were supported by protein data which revealed increased LC3-II levels in all α1 and α2 cells treated with 4-PBA clearly indicating a stimulation of autophagy (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

4-PBA ameliorates OI fibroblasts homeostasis by stimulating autophagy. (A) Histone H3 acetylation was investigated by Western blot analyses. 4-PBA increased the level of the H3 modification in all cells with the exception of the α1-G478S. (B) The expression of the autophagic gene ATG5, evaluated by qPCR, was increased by the treatment in all cells with the exception of α1-G478S. (C) LC3 Western blot analyses in the presence of chloroquine revealed increased LC3-II levels in all α1 and α2 cells after the 4-PBA treatment, clearly indicating a stimulation of autophagy.

Thus in the analyzed OI fibroblasts 4-PBA, stimulating both protein secretion and autophagy, helps the clearance of the engorged cells with positive effects on cell homeostasis and a reduction of cell death.

4. Discussion

The symptoms of skeletal dysplasias have been previously attributed to the dominant negative effect of structural abnormal collagen on extracellular matrix. Only recently, the cellular malfunction caused by mutated proteins retention in the endoplasmic reticulum has been demonstrated to play a key role in modulating the phenotype severity in several diseases including skeletal disorders due to mutations in ECM molecules such as the fibrillar collagen types II and X [17,40]. Here, we utilize fibroblasts from 10 OI patients producing structurally abnormal type I collagen, 5 each with glycine substitutions in the α1(I) and α2(I) chains, to investigate the effect of its intracellular retention (Table 1). Type I collagen is the major protein component of the ECM of bone and skin and is the most abundant protein synthesized by fibroblasts. We demonstrated the activation of the PERK UPR branch, with increased p-PERK/PERK ratio and increased expression of its downstream effector ATF4 (Fig. 2A-B). The activation of the UPR branch mediated by PERK has been described in the Amish murine model for dominant OI, carrying the α2(I)-G610C substitution [9], in the OI Dachshund dog homozygous for a defect in HSP47 [41], and in human OI type XIV patients lacking the expression of TRIC-B [42]. However, we also demonstrated the activation of the IRE1α UPR branch, especially, though not exclusively, in fibroblasts with α2(I) substitutions, which has not been previously reported in OI. Both PERK and IRE1α are type I transmembrane proteins sharing similar ER luminal domain structure and cytosolic Ser/Thr kinase domain, thus what determines the activation of one or the other or both pathways is difficult to dissect. The type and duration of intracellular insult as well as the structural differences between IRE and PERK lumen sensing domain were hypothesized as possible modulators of their response to cell stress [43]. Interestingly, the activation of IRE1α is reported to occur first following an ER insult favoring cytoprotective response, and to be attenuated during persistent ER stress, whereas PERK signaling, including translational inhibition and proapoptotic activation, is maintained and associated with cell death. Based on this observation, we can speculate that a prolonged presence of higher amount of mutated collagen due to α1 mutations, 75% compared to 50% mutant molecules when the mutation is in α2, is causing a more severe stress following misfolded protein retention. The ER lumen domain of the three UPR sensors PERK, Ire1α and ATF6 is associated with BIP, the major ER chaperone that upon ER stress is released to favor proper protein folding [44]. The puzzling behavior of BIP in OI cells has contributed to confusion concerning UPR activation as consequence of aberrant type I collagen. Immunoprecipitation studies demonstrated that retained mutant procollagen in OI primary fibroblasts is bound by BIP in presence of C-propeptide mutations, but not in presence of mutations in the triple helical domain [15,16]. Western blot analyses of primary osteoblasts from the OI Aga2 mouse model, harboring a proα1(I) C-terminal frameshift and from the α2(I)-G610C mouse revealed an upregulation of BIP in the former, but not in the latter. Interestingly, we found that BIP was upregulated in 3 of 5 helical mutations in α1(I) and α2(I) chains (Fig. 2A-B). It is possible that the use of fibroblasts, and the different type/position of substitution may explain the diverse response compared with the Amish model. In addition, based on the IRE1 crystal structure and detailed kinetic studies of BIP interaction with various UPR sensors, it has been proposed that other regulatory mechanisms or components in addition to BIP are involved in UPR activation following ER stress [45,46].

When UPR fails to reduce the ER overload, autophagy, a highly conserved cellular process regulating the turnover of cytoplasmic materials via a lysosome-dependent pathway, may be activated [47]. Indeed, in OI fibroblasts the prolonged stress caused by the continuous synthesis and intracellular accumulation of mutant collagen causes autophagy upregulation (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Our observation is in agreement with the literature data which identify autophagy as the preferential degradation pathway to eliminate over-glycosylated trimeric procollagen I molecules [9,13,48]. Autophagy is significantly activated in all mutant COL1A1 cells, but only in two mutant COL1A2 cells. Considering the stoichiometric composition of type I collagen, it may be that a minimal threshold of mutant molecules is required to activate autophagy, although we cannot exclude a role for the type/position of the α2(I) mutation in modulating autophagy, since 2 of the 5 α2(I) mutations increased this degradation pathway (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Autophagy has a well-known cytoprotective role in various disorders and its cell protective role in presence of ER stress has been as well reported [47,49,50]. The failure of autophagy to rescue cellular homeostasis in OI cells sets in motion the path to apoptotic death (Fig. 5). Similarly, the intracellular accumulation of abnormal proα1(I) in the Aga2 OI mouse induces caspases-12 and 3 activation, leading to osteoblast apoptosis [10], while in the Amish mouse model upregulation of the general stress response protein CHOP was detected, promoting apoptosis [9]. It is interesting that we detected apoptosis even in the α1-G226S fibroblasts, which have minimal overglycosylation because of the N-terminal location of this glycine substitution. G226 is located in close proximity to a HSP47 binding site, which has recently been reported to play a role in collagen sorting from the ER [5,51]. Thus, it is tempting to hypothesize that autophagy and apoptosis of G226S cells may reflect an effect on collagen sorting, since the collagen structure and modifications are minimally altered. The demonstration of apoptosis in α2-G640C cells is more puzzling, since neither UPR nor autophagy activation were detected. We can speculate that the substituting cysteine might form detrimental disulphide bonds between procollagen molecules or other ER resident proteins, impairing mutant collagen secretion from the ER. Of note, among the available OI fibroblasts we had the opportunity to analyze cells carrying an identical α1-G667R substitution, but isolated from patients with markedly different phenotypes, severe OI type III (α1-G667RIII) or lethal OI type II (α1-G667RII). The α1-G667RIII cells, but not the G667RII, showed upregulation of PDI, a chaperone favoring collagen chain recognition and folding, and of IRE1α, the more cytoprotective UPR transducer (Fig. 2A). These data may be relevant to the mechanism of their phenotypic variability. Especially in the α1(I) chain, patients with identical substitution of the same glycine residue may have lethal or non-lethal phenotypes, which is problematic for genetic counselling. In the Brtl OI mouse model, the α1(I) G349C substitution generates distinct moderate and lethal outcomes. Using bone and skin samples, we excluded that Brtl phenotype variability was due to differences in collagen structure, physical properties or interaction between mutant collagen helices [7]. Instead, using microarray and proteomic analysis, we found different intracellular responses to mutant collagen retention in the two phenotypes [25,26]. Similarly, we have confirmed in patients cells that the ability to manage cell stress can affect cellular homeostasis in the presence of identical mutations. No specific differences in cellular homeostasis were identified between the other lethal and non-lethal cells carrying different mutations.

Chemical chaperones have been used to alleviate cellular stress in several conditions with perturbed ER homeostasis. This is an appealing approach since several molecules with chaperone function are FDA-approved for other indications and already have a good safety record [[52], [53], [54]]. The chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyric acid (4-PBA) is FDA-approved for urea cycle disorders based on its ammonia scavenger activity [37]. 4-PBA is also able to increase ER folding capacity by facilitating proper folding and decreasing the accumulation and aggregation of misfolded proteins in the ER lumen [20]. Interestingly, amelioration of the cellular phenotype upon 4-PBA treatment was previously reported in dermal fibroblasts with COL4A2 mutations [21]. Here, 4-PBA treatment of cells with α1(I) mutations decreased or/and normalized PDI and p-PERK/PERK expression and decreased apoptosis (Fig. 6). Only fibroblasts carrying the α1-G226S and α2-G859C OI mutations showed no effect on apoptosis (Fig. 6). This may be related to the proximity of these substitutions to the HSP47 binding sites on collagen. The overall effect of 4-PBA on cells with α2(I) mutations was more subtle than for α1(I) mutations, pointing to a possible effect of the mutant chain itself. Both stress and apoptotic markers were decreased in cells with α2-G697C and α2-G745C mutations (Fig. 6B). Not surprisingly, no effect was found in α2-G640C, in which no UPR was detected in the basal state and for which the molecular basis of apoptosis need to be further evaluated. The molecular basis of 4-PBA effect on our in vitro system is related to both chaperone and autophagy effects. Following drug administration, we saw an increase of general protein secretion in all cells, which had been severely reduced in untreated cells, perhaps related to effects of mutant collagen on the general ER folding machinery (Fig. 7A). In the cells with the most C-terminal mutation, we also detected improved collagen secretion (Fig. 7B). We conclude that 4-PBA facilitates the ER folding machinery, impaired in stress condition, ameliorating cell homeostasis as demonstrated by the reduced PERK and apoptosis activation. This effect may also account for the amelioration in collagen secretion although probably in a mutation dependent manner. Our recent corroborative data in the Chihuahua (Chi/+) zebrafish model for classical OI displayed an increased amount of type I collagen in the Chi/+ tail upon tail clip and regrowth in the presence of 4-PBA [22].

Treated mutant fibroblasts showed a significant increase of LC3II expression, highlighting a role for 4-PBA as autophagic inducer and suggesting a complementary process of autophagy may favor the degradation of retained unfolded proteins [55]. Indeed 4-PBA-mediated autophagy upregulation has been recently described in hepatocyte cells [56] and induction of autophagy rescued the bone matrix deposition by cultured osteoblasts of the OI Amish model [9]. Moreover, autophagy was reported to play an essential role in protecting cells against the toxicity of TGF-β induced type I procollagen accumulation in the ER [57]. Furthermore, inhibition of autophagy by specific inhibitors or RNAi-mediated knockdown of an autophagy-related gene significantly stimulated accumulation of aggregated procollagen trimers in the ER, while its activation with rapamycin resulted in reduction of aggregates [13,50].

The question to be addressed was how 4-PBA could act as autophagy inducer in our in vitro model. Since the upregulation of ATG5 expression following 4-PBA administration was previously reported in human macrophages infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis we investigated the other known function of 4-PBA as histone deacetylase inhibitor [39,58]. We found that 4-PBA-increased levels of histone H3 acetylation (Fig. 8A) was associated with significantly increased expression of the autophagic gene ATG5 (Fig. 8B). Although mRNA or protein expression levels are not considered appropriate indicators for monitoring autophagy, ATG5 upregulation associated with increased autophagy (Fig. 8C) suggests that a transcriptional regulation of autophagic genes may be activated by 4-PBA histone deacetylase inhibitory activity.

Our study identified ER stress and autophagy as two potential targets for OI treatment. The data suggest that chaperone activity and autophagy may act as critical modifiers of the severity of collagen I disease. Manipulation of cellular pathways to modulate the OI phenotype may be easier than targeting the structural abnormalities in matrix, and may produce significant amelioration in clinical severity.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Effect of 4-PBA on the expression of ATG5 normalized to β-actin (ACTB) evaluated by qPCR.

Expression level of proteins involved in the UPR, autophagy and apoptosis in OI fibroblasts with mutations in COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes as determined by Western blot analyses.

Expression level of p-PERK/PERK and cleaved caspase 3 in OI fibroblasts with mutations in COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes after the treatment with 4-PBA as determined by Western blot analyses.

Funding

This work was supported by Fondazione Cariplo [grant No. 2013-0612], Telethon [grant No. GGP13098] and the European Community, FP7, ‘Sybil’ project [grant No. 602300] to AF; and by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro [Start-up grant No. 12710] and the European Commission [grant No. PCIG10-GA-2011-303806] to SS.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Patrizia Vaghi, Centro Grandi Strumenti, University of Pavia, Italy, for technical assistance with confocal microscopy, Mr. Angelo Gallanti for technical assistance with cell culture and Prof. Ivana Scovassi for the careful reading of the manuscript.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found, in online version.

Contributor Information

Roberta Besio, Email: roberta.besio@unipv.it.

Giusy Iula, Email: giusy.iula01@universitadipavia.it.

Nadia Garibaldi, Email: nadia.garibaldi01@universitadipavia.it.

Lina Cipolla, Email: lina.cipolla@igm.cnr.it.

Simone Sabbioneda, Email: simone.sabbioneda@igm.cnr.it.

Marco Biggiogera, Email: marco.biggiogera@unipv.it.

Joan C. Marini, Email: marinij@mail.nih.gov.

Antonio Rossi, Email: antrossi@unipv.it.

Antonella Forlino, Email: aforlino@unipv.it.

References

- 1.Forlino A., Marini J.C. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet. 2016;387:1657–1671. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00728-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forlino A., Cabral W.A., Barnes A.M., Marini J.C. New perspectives on osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:540–557. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sillence D.O., Senn A., Danks D.M. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Med. Genet. 1979;16:101–116. doi: 10.1136/jmg.16.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taga Y., Kusubata M., Ogawa-Goto K., Hattori S. Site-specific quantitative analysis of overglycosylation of collagen in osteogenesis imperfecta using hydrazide chemistry and SILAC. J. Proteome Res. 2013;12:2225–2232. doi: 10.1021/pr400079d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeney S.M., Orgel J.P., Fertala A., McAuliffe J.D., Turner K.R., Di Lullo G.A., Chen S., Antipova O., Perumal S., Ala-Kokko L. Candidate cell and matrix interaction domains on the collagen fibril, the predominant protein of vertebrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:21187–21197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709319200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marini J.C., Forlino A., Cabral W.A., Barnes A.M., San Antonio J.D., Milgrom S., Hyland J.C., Korkko J., Prockop D.J., De Paepe A. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum. Mutat. 2007;28:209–221. doi: 10.1002/humu.20429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forlino A., Kuznetsova N.V., Marini J.C., Leikin S. Selective retention and degradation of molecules with a single mutant alpha1(I) chain in the Brtl IV mouse model of OI. Matrix Biology: Journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2007;26:604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daley E., Streeten E.A., Sorkin J.D., Kuznetsova N., Shapses S.A., Carleton S.M., Shuldiner A.R., Marini J.C., Phillips C.L., Goldstein S.A. Variable bone fragility associated with an Amish COL1A2 variant and a knock-in mouse model. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25:247–261. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirigian L.S., Makareeva E., Mertz E.L., Omari S., Roberts-Pilgrim A.M., Oestreich A.K., Phillips C.L., Leikin S. Osteoblast malfunction caused by cell stress response to procollagen misfolding in a2(I)-G610C mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. JBMR. 2016;31:1608–1616. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lisse T.S., Thiele F., Fuchs H., Hans W., Przemeck G.K., Abe K., Rathkolb B., Quintanilla-Martinez L., Hoelzlwimmer G., Helfrich M. ER stress-mediated apoptosis in a new mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. PLoS Genet. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiansen H.E., Schwarze U., Pyott S.M., AlSwaid A., Al Balwi M., Alrasheed S., Pepin M.G., Weis M.A., Eyre D.R., Byers P.H. Homozygosity for a missense mutation in SERPINH1, which encodes the collagen chaperone protein HSP47, results in severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alanay Y., Avaygan H., Camacho N., Utine G.E., Boduroglu K., Aktas D., Alikasifoglu M., Tuncbilek E., Orhan D., Bakar F.T. Mutations in the gene encoding the RER protein FKBP65 cause autosomal-recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishida Y., Nagata K. Autophagy eliminates a specific species of misfolded procollagen and plays a protective role in cell survival against ER stress. Autophagy. 2009;5:1217–1219. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.8.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hetz C., Chevet E., Oakes S.A. Proteostasis control by the unfolded protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:829–838. doi: 10.1038/ncb3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chessler S.D., Byers P.H. BiP binds type I procollagen pro alpha chains with mutations in the carboxyl-terminal propeptide synthesized by cells from patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:18226–18233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamande S.R., Chessler S.D., Golub S.B., Byers P.H., Chan D., Cole W.G., Sillence D.O., Bateman J.F. Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated quality control of type I collagen production by cells from osteogenesis imperfecta patients with mutations in the pro alpha 1 (I) chain carboxyl-terminal propeptide which impair subunit assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:8642–8649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boot-Handford R.P., Briggs M.D. The unfolded protein response and its relevance to connective tissue diseases. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:197–211. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0877-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsang K.Y., Chan D., Bateman J.F., Cheah K.S. In vivo cellular adaptation to ER stress: survival strategies with double-edged consequences. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:2145–2154. doi: 10.1242/jcs.068833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen F.E., Kelly J.W. Therapeutic approaches to protein-misfolding diseases. Nature. 2003;426:905–909. doi: 10.1038/nature02265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iannitti T., Palmieri B. Clinical and experimental applications of sodium phenylbutyrate. Drugs in R&D. 2011;11:227–249. doi: 10.2165/11591280-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray L.S., Lu Y., Taggart A., Van Regemorter N., Vilain C., Abramowicz M., Kadler K.E., Van Agtmael T. Chemical chaperone treatment reduces intracellular accumulation of mutant collagen IV and ameliorates the cellular phenotype of a COL4A2 mutation that causes haemorrhagic stroke. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:283–292. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gioia R., Tonelli F., Ceppi I., Biggiogera M., Leikin S., Fisher S., Tenedini E., Yorgan T.A., Schinke T., Tian K. The chaperone activity of 4PBA ameliorates the skeletal phenotype of Chihuahua, a zebrafish model for dominant osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017;26:2897–2911. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashinsky B.G., Fishbein K.W., Carter E.M., Lin P.C., Pleshko N., Raggio C.L., Spencer R.G. Multiparametric classification of skin from osteogenesis imperfecta patients and controls by quantitative magnetic resonance microimaging. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balasubramanian M., Sobey G.J., Wagner B.E., Peres L.C., Bowen J., Bexon J., Javaid M.K., Arundel P., Bishop N.J. Osteogenesis imperfecta: ultrastructural and histological findings on examination of skin revealing novel insights into genotype-phenotype correlation. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2016;40:71–76. doi: 10.3109/01913123.2016.1140253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forlino A., Tani C., Rossi A., Lupi A., Campari E., Gualeni B., Bianchi L., Armini A., Cetta G., Bini L. Differential expression of both extracellular and intracellular proteins is involved in the lethal or nonlethal phenotypic variation of BrtlIV, a murine model for osteogenesis imperfecta. Proteomics. 2007;7:1877–1891. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bianchi L., Gagliardi A., Gioia R., Besio R., Tani C., Landi C., Cipriano M., Gimigliano A., Rossi A., Marini J.C. Differential response to intracellular stress in the skin from osteogenesis imperfecta Brtl mice with lethal and non lethal phenotype: a proteomic approach. J. Proteome. 2012;75:4717–4733. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bianchi L., Gagliardi A., Maruelli S., Besio R., Landi C., Gioia R., Kozloff K.M., Khoury B.M., Coucke P.J., Symoens S. Altered cytoskeletal organization characterized lethal but not surviving Brtl+/− mice: insight on phenotypic variability in osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;24:6118–6133. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mottes M., Gomez Lira M., Zolezzi F., Valli M., Lisi V., Freising P. Four new cases of lethal osteogenesis imperfecta due to glycine substitutions in COL1A1 and genes. Mutations in brief no. 152. Online. Hum. Mutat. 1998;12:71–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:1<71::AID-HUMU16>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomez-Lira M., Sangalli A., Pignatti P.F., Digilio M.C., Giannotti A., Carnevale E., Mottes M. Determination of a new collagen type I alpha 2 gene point mutation which causes a Gly640 Cys substitution in osteogenesis imperfecta and prenatal diagnosis by DNA hybridisation. J. Med. Genet. 1994;31:965–968. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.12.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venturi G., Tedeschi E., Mottes M., Valli M., Camilot M., Viglio S., Antoniazzi F., Tato L. Osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical, biochemical and molecular findings. Clin. Genet. 2006;70:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valli M., Mottes M., Tenni R., Sangalli A., Gomez Lira M., Rossi A., Antoniazzi F., Cetta G., Pignatti P.F. A de novo G to T transversion in a pro-alpha 1 (I) collagen gene for a moderate case of osteogenesis imperfecta. Substitution of cysteine for glycine 178 in the triple helical domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:1872–1878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makareeva E., Mertz E.L., Kuznetsova N.V., Sutter M.B., DeRidder A.M., Cabral W.A., Barnes A.M., McBride D.J., Marini J.C., Leikin S. Structural heterogeneity of type I collagen triple helix and its role in osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:4787–4798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green D.R., Levine B. To be or not to be? How selective autophagy and cell death govern cell fate. Cell. 2014;157:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yin Z., Pascual C., Klionsky D.J. Autophagy: machinery and regulation. Microb Cell. 2016;3:588–596. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.12.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galluzzi L., Baehrecke E.H., Ballabio A., Boya P., Bravo-San Pedro J.M., Cecconi F., Choi A.M., Chu C.T., Codogno P., Colombo M.I. Molecular definitions of autophagy and related processes. EMBO J. 2017;36:1811–1836. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barth S., Glick D., Macleod K.F. Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J. Pathol. 2010;221:117–124. doi: 10.1002/path.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matoori S., Leroux J.C. Recent advances in the treatment of hyperammonemia. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015;90:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Portela A., Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fass D.M., Shah R., Ghosh B., Hennig K., Norton S., Zhao W.N., Reis S.A., Klein P.S., Mazitschek R., Maglathlin R.L. Effect of inhibiting histone deacetylase with short-chain carboxylic acids and their hydroxamic acid analogs on vertebrate development and neuronal chromatin. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;2:39–42. doi: 10.1021/ml1001954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gawron K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in chondrodysplasias caused by mutations in collagen types II and X. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2016;21:943–958. doi: 10.1007/s12192-016-0719-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindert U., Weis M.A., Rai J., Seeliger F., Hausser I., Leeb T., Eyre D., Rohrbach M., Giunta C. Molecular consequences of the SERPINH1/HSP47 mutation in the dachshund natural model of osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:17679–17689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.661025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabral W.A., Ishikawa M., Garten M., Makareeva E.N., Sargent B.M., Weis M., Barnes A.M., Webb E.A., Shaw N.J., Ala-Kokko L. Absence of the ER Cation Channel TMEM38B/TRIC-B disrupts intracellular calcium homeostasis and dysregulates collagen synthesis in recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. PLoS Genet. 2016;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DuRose J.B., Tam A.B., Niwa M. Intrinsic capacities of molecular sensors of the unfolded protein response to sense alternate forms of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:3095–3107. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-01-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J., Ni M., Lee B., Barron E., Hinton D.R., Lee A.S. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP is required for endoplasmic reticulum integrity and stress-induced autophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1460–1471. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou J., Liu C.Y., Back S.H., Clark R.L., Peisach D., Xu Z., Kaufman R.J. The crystal structure of human IRE1 luminal domain reveals a conserved dimerization interface required for activation of the unfolded protein response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:14343–14348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606480103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrara M., Prischi F., Nowak P.R., Ali M.M. Crystal structures reveal transient PERK luminal domain tetramerization in endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. EMBO J. 2015;34:1589–1600. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogata M., Hino S., Saito A., Morikawa K., Kondo S., Kanemoto S., Murakami T., Taniguchi M., Tanii I., Yoshinaga K. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:9220–9231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawasaki K., Ushioda R., Ito S., Ikeda K., Masago Y., Nagata K. Deletion of the collagen-specific molecular chaperone Hsp47 causes endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:3639–3646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.592139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levine B., Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bartolome A., Guillen C., Benito M. Autophagy plays a protective role in endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated pancreatic beta cell death. Autophagy. 2012;8:1757–1768. doi: 10.4161/auto.21994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ishikawa Y., Ito S., Nagata K., Sakai L.Y., Bachinger H.P. Intracellular mechanisms of molecular recognition and sorting for transport of large extracellular matrix molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016;113:E6036–E6044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609571113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Makareeva E., Aviles N.A., Leikin S. Chaperoning osteogenesis: new protein-folding disease paradigms. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Briggs M.D., Bell P.A., Wright M.J., Pirog K.A. New therapeutic targets in rare genetic skeletal diseases. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2015;3:1137–1154. doi: 10.1517/21678707.2015.1083853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ashburn T.T., Thor K.B. Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:673–683. doi: 10.1038/nrd1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galluzzi L., Bravo-San Pedro J.M., Levine B., Green D.R., Kroemer G. Pharmacological modulation of autophagy: therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:487–511. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nissar A.U., Sharma L., Mudasir M.A., Nazir L.A., Umar S.A., Jr., Sharma P.R., Vishwakarma R.A., Tasduq S.A. Chemical chaperone 4-phenyl butyric acid (4PBA) reduces hepatocellular lipid accumulation and lipotoxicity through induction of autophagy. J. Lipid Res. 2017;58:1855–1868. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M077537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim S.I., Na H.J., Ding Y., Wang Z., Lee S.J., Choi M.E. Autophagy promotes intracellular degradation of type I collagen induced by transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:11677–11688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rekha R.S., Rao Muvva S.S., Wan M., Raqib R., Bergman P., Brighenti S., Gudmundsson G.H., Agerberth B. Phenylbutyrate induces LL-37-dependent autophagy and intracellular killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Autophagy. 2015;11:1688–1699. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1075110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Effect of 4-PBA on the expression of ATG5 normalized to β-actin (ACTB) evaluated by qPCR.

Expression level of proteins involved in the UPR, autophagy and apoptosis in OI fibroblasts with mutations in COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes as determined by Western blot analyses.

Expression level of p-PERK/PERK and cleaved caspase 3 in OI fibroblasts with mutations in COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes after the treatment with 4-PBA as determined by Western blot analyses.

Transparency document.