Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is generally a fatal disease with no efficacious treatment modalities. Elucidation of signaling mechanisms that will lead to the identification of novel targets for therapy and chemoprevention is urgently needed. Here, we review the role of Yes-associated protein (YAP) and WW-domain-containing Transcriptional co-Activator with a PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) in the development of PDAC. These oncogenic proteins are at the center of a signaling network that involves multiple upstream signals and downstream YAP-regulated genes. We also discuss the clinical significance of the YAP signaling network in PDAC using a recently published interactive open-access database (www.proteinatlas.org/pathology) that allows genome-wide exploration of the impact of individual proteins on survival outcomes. Multiple YAP/TEAD-regulated genes, including AJUBA, ANLN, AREG, ARHGAP29, AURKA, BUB1, CCND1, CDK6, CXCL5, EDN2, DKK1, FOSL1,FOXM1, HBEGF, IGFBP2, JAG1, NOTCH2, RHAMM, RRM2, SERP1, and ZWILCH, are associated with unfavorable survival of PDAC patients. Similarly, components of AP-1 that synergize with YAP (FOSL1), growth factors (TGFα, EPEG, and HBEGF), a specific integrin (ITGA2), heptahelical receptors (P2Y2R, GPR87) and an inhibitor of the Hippo pathway (MUC1), all of which stimulate YAP activity, are associated with unfavorable survival of PDAC patients. By contrast, YAP inhibitory pathways (STRAD/LKB-1/AMPK, PKA/LATS, and TSC/mTORC1) indicate a favorable prognosis. These associations emphasize that the YAP signaling network correlates with poor survival of pancreatic cancer patients. We conclude that the YAP pathway is a major determinant of clinical aggressiveness in PDAC patients and a target for therapeutic and preventive strategies in this disease.

Pancreatic cancer: Signaling network linked to patient survival

Yes-associated protein (YAP) signaling contributes to pancreatic cancer progression and is associated with poor patient survival. Previous studies have shown that YAP activates genes involved in cell proliferation to incite tumor growth and metastasis. Enrique Rozengurt and colleagues at University of California Los Angeles review the latest knowledge on YAP signaling and used the open access database The Human Protein Atlas to analyze the gene expression profile and prognosis of 176 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Activation of upstream or downstream elements of the YAP signaling pathway correlated with shorter survival in patients. Conversely, the activation of signaling pathways that oppose YAP signaling were associated with a more favorable prognosis. These findings highlight YAP signaling pathway components as both prognostic markers and potential targets for developing much needed therapeutic and preventative strategies.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer, of which pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) represents the most common histological subtype, is one of the most lethal human diseases, with overall 5-year survival rates of 7% and a median survival period of 4–6 months1. The incidence of this disease in the United States is estimated to increase to 53,670 new cases in 2017. Indeed, deaths due to PDAC are projected to increase dramatically, making the disease the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the USA before 20302. Novel targets and agents for therapy and chemoprevention are urgently needed and will most likely arise from a more detailed understanding of the signaling mechanisms that stimulate the promotion and progression of sub-malignant (initiated) cells into pancreatic cancer cells and from the identification of modifiable risk factors for PDAC. Identification of the molecular mechanisms of PDAC promotion and drug resistance will clearly guide the discovery of novel targets, prognostic markers, agents for therapy and prevention and will identify effective signature markers for use in specific and personalized therapeutic procedures.

PDAC arises from the evolution of precursor lesions, the most common of which are pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanINs). Progression from these noninvasive ductal lesions to in situ carcinomas and invasive cancers is associated with the accumulation of genetic alterations, including activation of mutations in the KRAS oncogene, which are widely accepted to represent an initiating event3. Accordingly, exome sequencing has established KRAS to be the most frequently mutated gene in PDAC (~95%)4, 5. The majority of all missense KRAS mutations in PDAC occur at position G12, with a G12D single amino acid substitution being the most prevalent. These mutations prevent interactions between KRAS-GTP and KRAS GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), thus leading to prolonged activation of KRAS and thereby to the activation of downstream signaling effectors, the best characterized of which are the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways6, 7. Genetically engineered mouse models that recapitulate many features of the human disease have defined a critical role for KrasG12D in the initiation and maintenance of PDAC3, 8, 9. The progression of pancreatic carcinogenesis requires stimulation of a set of signaling pathways that lead to sustained cell proliferation4. Although, a KRAS mutation is an early and necessary event in the development of PDAC, it is not sufficient to promote the complete carcinogenic process. Activation of other pathways by additional mutations, including mutations in tumor suppressor genes, such as TP53, one of the most frequently mutated genes in human cancer, CDKN2A, the gene encoding p16 and p14, and SMAD4 and/or environmental stimuli (obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus) are required for the promotion of invasive PDAC. This article highlights a striking association between a signal transduction network and the overall survival of patients with PDAC.

The hippo/yap/taz pathway and pdac

The transcriptional co-activators yes-associated protein (YAP)10 and its paralog WW-domain-containing Transcriptional co-Activator with a PDZ-binding motif (TAZ)11 are attracting intense attention as fundamental points of convergence and intersection of many signal transduction pathways that are implicated in the regulation of development, metabolism, organ-size, positional sensing, tissue regeneration and tumorigenesis12–14. Indeed, multiple products of the YAP/TEAD-regulated gene network have a major impact on these important processes, and YAP and TAZ are increasingly recognized as potent oncogenes in many cancer types15, especially in PDAC16–19. After a succinct overview of the YAP/TAZ network in PDAC, the basic tenet of this article will be to emphasize the association between the expression of each element of the network and patient overall survival. Therefore, this review integrates signal transduction and patient survival, and thus differs in focus from many recent excellent reviews on the Hippo/YAP/TAZ pathway that are available in the literature12–15, 20.

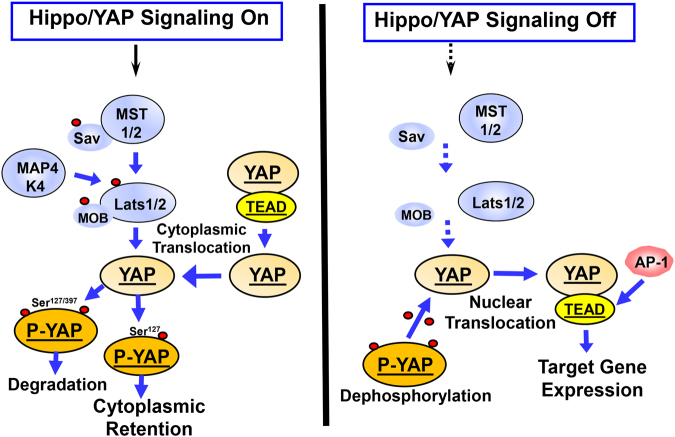

It is widely recognized that a major factor in the regulation of YAP/TAZ activity is the Hippo pathway, which was originally identified in Drosophila12. Canonical Hippo signals are transduced through a serine/threonine kinase cascade, wherein Mst1/2 kinases, in complex with Sav1, phosphorylate and activate Lats1/2 in complex with its regulatory protein MOB1/2 (Fig. 1). In addition to Mst1/2, Hppy/MAP4Ks were identified as alternative kinases that phosphorylate Lats1/221. In turn, Lats1/2 phosphorylates YAP and TAZ, two major downstream effectors of the Hippo pathway and novel sensors of the mevalonate and glycolytic pathways13, 22, 23. Structurally, YAP and TAZ share nearly half of their overall amino acid sequences, and have very similar topologies and highly conserved residues that are located within a consensus sequence that is phosphorylated by Lats1/2 (HXRXXS). The phosphorylation of YAP by Lats1/2 at Ser-127 and Ser-397 (and equivalent residues in TAZ) restricts its cellular localization to the cytoplasm and reduces the protein’s stability (Fig. 1). When the Hippo pathway is not functional, YAP and TAZ are dephosphorylated and translocated to the nucleus where they bind to and activate a number of transcription factors, primarily the TEA-domain DNA-binding transcription factors (TEAD 1–4). In this manner, nuclear YAP and TAZ promote the expression of multiple genes (Fig. 1). Accordingly, YAP and TAZ display a degree of functional redundancy15, 20 but also differ in a number of ways. For example, YAP negatively regulates TAZ, while TAZ expression levels do not modulate YAP levels24. TAZ is more unstable than YAP, thus these oncogenic proteins often are differentially expressed in different cancer cell types25. Therefore, activation of the tumor suppressor Hippo pathway in response to multiple environmental cues, including cell/cell contacts, cell polarity and mechanical tension, potently inhibits the transcriptional co-activator activity of YAP and TAZ and leads to the degradation of TAZ12, 15, 26–28.

Fig. 1.

Hippo signaling phosphorylates YAP and regulates its nuclear/cytoplasmic distribution. When Hippo signaling is active (e.g., in response to cell density, polarity signals, or mechanical cues) the Mst1/2 kinases, in complex with Sav1, phosphorylate and activate Lats1/2 in complex with its regulatory protein MOB1/2. In addition to Mst1/2, MAP4Ks act as alternative kinases that phosphorylate Lats1/2. In turn, Lats1/2 phosphorylates YAP on highly conserved residues (in red) located within a consensus sequence that is phosphorylated by Lats1/2 (HXRXXS). The phosphorylation of YAP at Ser-127 promotes its cytoplasmic retention, whereas phosphorylation at Ser-397 induces degradation. When the Hippo pathway is off, YAP is dephosphorylated and translocated into the nucleus where YAP binds and activates the TEAD transcription factors and stimulates the expression of multiple genes. Additional details are provided in the text

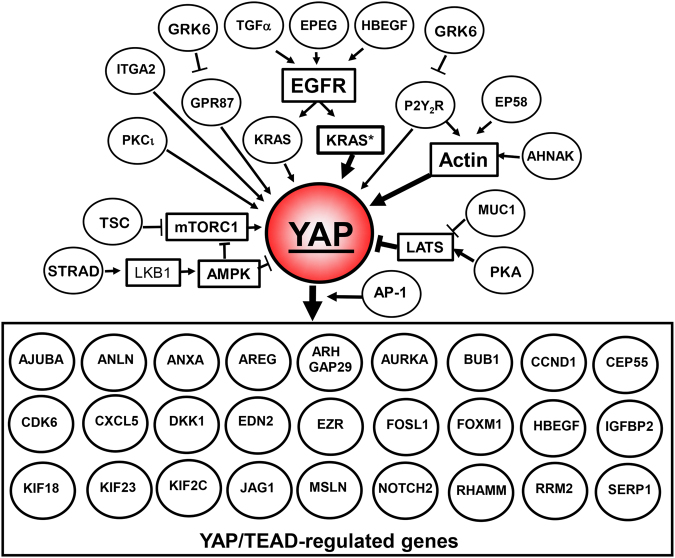

By contrast, multitude upstream pathways positively control YAP/TAZ transcriptional co-activator activity. These include signals mediated by ligand-activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), tyrosine kinase receptors, integrins and mechanical cues (Fig. 2). A variety of signaling pathways that are activated by these receptors, including PI3K, mTOR, PKD, and Rho/actin cytoskeleton, feed into the YAP/TAZ pathway12, 15, 26–28. For example, a recent study with human PDAC cells demonstrated that crosstalk between insulin/IGF-1 receptor and GPCR systems29, 30 regulates YAP localization, phosphorylation, and transcriptional co-activator activity through PI3K and PKD31. Accordingly, recent studies with other cell types demonstrated that PI3K inhibits the activity of the Hippo pathway32, 33, thereby promoting YAP activity. Other studies have demonstrated that PKD, a key node downstream of GPCRs34, 35, stimulates the nuclear localization of YAP and the activation of YAP/TEAD-regulated gene expression, most likely by stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton28. Thus, extracellular stimuli can control YAP/TAZ activity via inhibition of the Hippo pathway and/or stabilization of the actin cytoskeleton, thereby regulating a complex program of gene expression (Fig. 2). A recent report indicated that in addition to YAP and TAZ, the TEAD transcription factors also shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm and that environmental stress promotes the cytoplasmic translocation of TEAD via p38 MAPK in a Hippo-independent manner, thus identifying an additional level of regulation36.

Fig. 2.

YAP is at the epicenter of a signaling network. Growth factors (TGFα, EPEG, and HBEGF) induce EGFR signaling leading to KRAS activation, which in turn, stimulates YAP activation and increased expression. Other tyrosine kinase receptors, a specific integrin (ITGA2), multiple GPCRs, an inhibitor of Hippo pathway (MUC1) and actin polymerization via multiple pathways also stimulate YAP activity. Activation of YAP stimulates its coupling with TEAD, thereby promoting the expression of multiple YAP/TEAD-regulated genes that were identified in screens in different cell types. Reference to the study or studies connecting each gene to YAP/TAZ, as well as further details concerning the network are in the text

The YAP/TAZ pathway assumes an added importance in PDAC because YAP is also a key downstream target of KRAS signaling16 that is required for acinar-to-ductal metaplasia (ADM) and PanIN progression into PDAC in genetically engineered mouse models16, 17. YAP is also a major mediator of pro-oncogenic mutant p53, resistance to RAF/MEK inhibitors and chemotherapy in PDAC37, 38, and TAZ supports development of pancreatic cancer39. Conversely, mutants that render p53 as a super suppressor of pancreatic cancer act via inactivation of Yap40. It is of interest that pancreas-specific deletion of Yap did not affect normal pancreatic development and endocrine functions, but blocked the progression of KrasG12D –induced evolution of PanINs to overt PDAC16.

In addition to the rapid regulation of YAP activity via phosphorylation and localization, additional pathways and epigenetic events regulate the level of YAP/TAZ protein expression. In this regard, the RAS pathway promotes YAP1 stability independent of the Hippo pathway through down regulation of the ubiquitin ligase complex substrate recognition factors SOCS5/6, thereby increasing YAP stability41. A recent study demonstrated that eIF5A (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 5A), which is up-regulated by KRAS in PDAC and in KC mice (i.e., mice harboring a Kras G12D), increases the tyrosine kinase PEAK1. In turn, the eIF5A/PEAK1 axis enhances the expression of YAP42. It is also relevant that YAP and mTORC1 form an amplification loop that enhances the expression of YAP protein. Specifically, YAP stimulates mTORC1 via down regulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and increases amino acid (leucine) transport43. In turn, the activation of mTORC1 leads to the accumulation of YAP through impaired autophagy44. The positive feedback loop between YAP and mTORC1 increases YAP activity and expression.

Recent studies have demonstrated that amplification and overexpression of YAP could substitute for mutant Kras in murine cancers19, 45. These findings raise the important notion that YAP not only acts downstream of Kras but also that hyper-activation and expression of YAP can circumvent the need for Kras mutant expression in PDAC3, 19. An important feature of PDAC is the recruitment of immune-suppressive leukocytes, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor-associated macrophages, that contribute to immune evasion3. Recently, YAP has been shown to play a critical role in promoting an immunosuppressive microenvironment via the production of multiple cytokines in PDAC46 and in other cancers47. Thus, there is substantial evidence from preclinical studies indicating that YAP/TAZ is at the epicenter of a signaling network that is of crucial importance in the development of PDAC. Our next objective is to focus on the importance of the YAP/TAZ pathway in human PDAC.

Clinical significance of yap: a prognostic marker in pdac

To assess the significance of the YAP pathway in human PDAC, we will discuss the importance of YAP as a prognostic marker of survival in patients with PDAC. A number of studies have indicated that YAP and TAZ are overactive in tumor samples from PDAC patients, as judged by their expression and or localization18, 19, 39. Furthermore, a recent report identified YAP expression as an independent prognostic marker for the overall survival of PDAC patients and its association with liver metastasis48. If YAP plays a critical role in the survival of PDAC patients, it is plausible that upstream and downstream elements of the network, as well as regulators of YAP activity that have been identified in a variety of cells, are also likely to be associated with survival of patients with PDAC, and can serve as prognostic markers. Given its important translational implications, we explored this proposition using a recently published interactive open-access database (www.proteinatlas.org/pathology) to perform correlation analyses based on mRNA expression levels of genes of the YAP pathway in PDAC tissue and the clinical outcome (survival) of the patients49. The data in the Pathology Atlas is based on the integration of publicly available data from The Cancer Genome Atlas and data generated within the framework of the Human Protein Atlas and analyzed transcriptomics and survival in 176 PDAC patients. The results are presented in the form of Kaplan–Meier plots and only differences in survival with a high statistical significance (p < 0.001) are taken into consideration. We also performed additional searches of the literature for studies using different patient cohorts that validate the conclusions drawn from the Pathology Atlas.

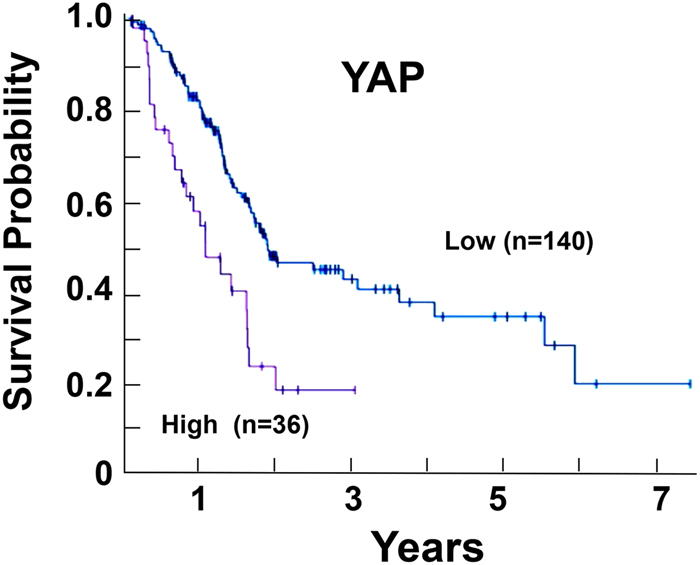

As expected, increased expression of YAP is associated significantly with an unfavorable prognosis (survival) in PDAC patients who were included in the Pathology Atlas49. Antibody staining, which is also included in the Pathology Atlas, is consistent with the mRNA expression data and is in agreement with other studies39, 48, localizes YAP/TAZ to the cancer cells. As illustrated in the Kaplan–Meier plot in Fig. 3, none of the patients of the population with higher levels of YAP mRNA expression (n = 36) survived for 5 years, although 32% of the population (n = 140) with lower levels of YAP mRNA survived for 5 years or more. In agreement with a recent report using a different cohort of patients48, an increase in the expression of YAP is an unfavorable prognostic marker for survival in patients with PDAC.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier plots for YAP expression in PDAC. The image was reproduced from the Human Protein Atlas (version 17) available at www.proteinatlas.org. The link is: http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000137693YAP1/pathology/tissue/pancreatic±cancer.

Molecules downstream and upstream of yap are unfavorable prognostic markers in pdac

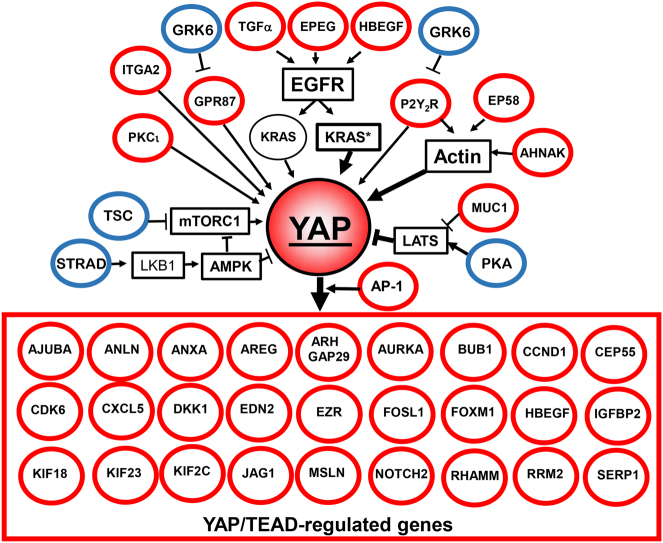

As indicated in previous sections, YAP and TAZ constitute points of convergence of multiple upstream pathways and in turn, regulate the expression of multiple genes. In most cases, the regulation of gene expression by YAP/TAZ/TEAD occurs via distal enhancer elements50. We performed a correlation analysis between mRNA expression of genes that are downstream targets of YAP/TAZ in a variety of cell types and survival of PDAC patients by mining the data that are available in the recently available Pathology Atlas49. As highlighted in Fig. 4, multiple YAP/TEAD-regulated genes are significantly associated (p < 0.001) with unfavorable prognosis in PDAC49. These include AJUBA50, ANLN51, ANXA350, AREG28, ARHGAP1952, ARHGAP2953, AURKA19, BUB119, 50, CCNA250, CCND150, 54, CDK650, 55, CEP5550, CXCL531, 47, 50, DKK150, 56, EDN250, 57, EZR50, 58, FOXM159, HBEGF50, IGFBP260, JAG150, 61, KIF2C50, KIF18B50, KIF2350, MSLN50, 62, NOTCH263, PRMT550, RRM250, SERP150, RHAMM23, and ZWILCH50. Each reference identifies the study or studies that connected the expression of the corresponding gene to YAP/TAZ/TEAD activity. In addition, independent studies using different patient populations demonstrated that the expression of YAP/TAZ/TEAD-regulated genes, including ANLN64, AREG65, CCND166, DKK167, EZR58, FOSL168, FOXM169, MSLN70, RHAMM71, RRM272, and SERP173, is associated with shorter survival in patients with PDAC.

Fig. 4.

YAP signaling is associated with unfavorable prognosis for PDAC. Multiple YAP/TEAD-regulated genes are associated with unfavorable survival of PDAC patients (indicated in red). Growth factors (TGFα, EPEG, and HBEGF), a specific integrin (ITGA2), GPCRs (P2Y2R, GPR87) or an inhibitor of the Hippo pathway (MUC1) that stimulate YAP activity are also associated with unfavorable survival in PDAC. Conversely, YAP inhibitory pathways, including STRAD/LKB-1, PKA/LATS, and TSC/mTORC1 are associated with a favorable prognosis (indicated in blue). The key feature is that each component of the network has an impact on survival of PDAC patients, as derived from the Pathology Atlas49, as well as additional references cited in the text. An unfavorable prognosis for PDAC is in red and a favorable prognosis for PDAC is in blue. All prognostic associations are highly statistically significant (p < 0.001). Further details are in the text

It is important to emphasize that the protein products of YAP/TEAD-regulated genes that are associated with PDAC survival regulate a set of fundamental biological processes in cancer development. For example, AREG, HBEGF, CCND1, and RRM2 stimulate cell proliferation; AURKA, BUB1, CEP55, KIF23, and ZWILCH participate in mitosis;68, 74 YAP cooperates with FOXM1 to promote chromosome instability59, and CXCL5 mediates communication between cancer cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells47, which contributes to the immunosuppressive microenvironment characteristic of PDAC. Other YAP/TEAD-regulated gene products are involved in the regulation of developmental pathways, including NOTCH, DKK1/WNT, and the Hippo pathway itself via AJUBA75. AURKA also inhibits LKB1/AMPK signaling thereby leading to YAP activation (see below). Furthermore, proteins that are encoded by the YAP-regulated genes EZR and IGFBP2 (ezrin and IGFBP2, respectively) promote metastasis and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in pancreatic cancer cells76. In turn, EMT contributes to the loss of cell polarity and thus to inhibition of the Hippo pathway, thereby reinforcing YAP activation. It is also of interest that the expression of some YAP/TEAD-regulated genes, including CTGF (encoding for connective tissue growth factor) have not been identified as prognostic markers of PDAC, but are likely to play a role in pancreatic carcinogenesis77.

In addition to AREG (amphiregulin) and HBEGF (heparin-binding EGF), which stimulate YAP/TEAD signaling via autocrine/paracrine stimulation of EGFR78 as part of positive feedback loops, other EGFR ligands, including TGFα and epiregulin (EPEG) that stimulate YAP activity are also associated with shorter overall survival in PDAC (Fig. 4). Similarly, the increased expression of MET79, ITGA280, IQGAP181, EZR82, MUC183, PRKC84, and YES185 which enhance YAP co-transcriptional activity through different mechanisms, is associated with shorter survival in patients with PDAC (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the activator protein-1 (AP-1, dimer of JUN and FOS proteins) factors have been shown to potentiate YAP/TAZ/TEAD-dependent gene expression via enhancers rather than promoters50. In line with the notion that YAP/TAZ is at the center of a signaling network that is associated with patient survival, the expression of FOSL1, a component of AP-1, is also strongly associated (p < 0.001) with an unfavorable prognosis in PDAC, as has also been shown recently in an independent report68.

GPCR signaling is one of the major upstream signals that regulate YAP/TAZ activation in a variety of systems, including PDAC31. In this context, the expression of genes encoding the lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptor GPR8786, the purinergic GPCR P2Y2R87 and the GPCR agonist EDN2 (endothelin 2)57, a downstream target of YAP, are also associated with an unfavorable prognosis in PDAC. A recent independent study confirmed that overexpression of GPR87 is correlated with a poor prognosis in PDAC88. By contrast, the expression of GRK6, which phosphorylates GPCRs thus opposing their signaling output89, is associated with a favorable survival prognosis in PDAC (Fig. 4).

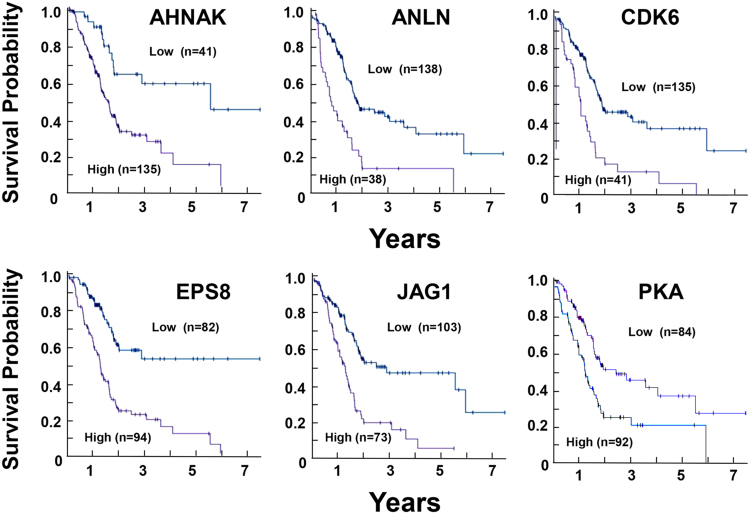

As mentioned above, the organization of the actin cytoskeleton is a master regulator of YAP/TAZ nuclear localization and activity90, 91. Interestingly, a number of proteins that are encoded by YAP/TEAD-regulated genes also influence the organization of the actin cytoskeleton, suggesting the existence of feedbacks loops. The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway substrate 8 (Eps8), a regulator of actin remodeling that is up-regulated in >70% of PDACs and induces YAP translocation to the nucleus and transcriptional activation92, is associated with an unfavorable prognosis in PDAC49. ANLN and AHNAK, proteins that are implicated in actin cytoskeleton organization93 and thus, potentially in YAP regulation, are also associated with unfavorable survival in PDAC. Indeed, AHNAK, ANLN, CDK6, EPS8, and JAG1 are among the genes with the highest significance associated with unfavorable prognoses in PDAC (Kaplan–Meier plots in Fig. 5; p < 4.1e−6) and are all either upstream or downstream of YAP/TEAD (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5.

Kaplan–Meier plots for gene expression of the YAP signaling network in PDAC. Images were reproduced from the Human Protein Atlas (version 17) available at www.proteinatlas.org. The links to the specific genes shown are as follows: AHNAK, http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000124942AHNAK/pathology/tissue/pancreatic±cancer, ANLN, http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000011426ANLN/pathology/tissue/pancreatic±cancer CDK6, http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000105810-CDK6/pathology/tissue/pancreatic±cancer EPS8, http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000151491-EPS8/pathology/tissue/pancreatic±cancer JAG1, http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000101384-JAG1/pathology/tissue/pancreatic±cancer PKA, http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000072062-PRKACA/pathology/tissue/pancreatic±cancer

Pathways that oppose yap signaling are favorable prognostic markers in pdac

In recent years, it has become apparent that, in addition to the cascade of Hippo kinases, other important pathways also inhibit YAP/TAZ functions. AMP–activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a well-known sensor of cellular energy that is activated when ATP concentrations decrease and 5′-AMP concentrations increase94. AMPK opposes YAP activity at different levels, including direct phosphorylation of YAP at Ser-94, a key residue for the interaction between YAP and TEAD35, 95. The tumor suppressor LKB-1/STK11 is the major kinase for phosphorylating the AMPK activation loop at Thr-17296. Interestingly, STE20-related adaptor (STRAD), a co-factor that allosterically stimulates LKB-1 activity and thus promotes AMPK activity, is a favorable prognostic marker in pancreatic cancer (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the protein kinases of the MARK family (e.g., MARK1) that also function downstream of LKB-1 and repress YAP activity97 are also associated with a favorable prognosis in pancreatic cancer.

A number of other studies have indicated that the cAMP/PKA pathway also inhibits YAP activity98, at least in part via stimulation of LATS kinases99. Accordingly, expression of PKA is associated with a favorable prognosis in PDAC, presumably via inhibition of YAP function (Fig. 4).

As mentioned above, mTORC1 is part of an amplification loop that leads to YAP expression and enhanced activity. The heterodimer of the tumor suppressors TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis 2, also known as tuberin) and TSC1 (tuberous sclerosis 1, also known as hamartin) opposes mTORC1 signaling100, 101 by acting as a GTPase-activator protein for the small G protein Rheb, a potent activator of mTORC1 signaling in its GTP-bound state102, 103. Importantly, increased expression of TSC2 and TSC1 is associated with a favorable prognosis for patients with PDAC (Fig. 4).

Targeting the yap signal transduction pathway

As a result of the developments discussed in this article, there is intense interest in targeting YAP/TAZ in PDAC therapy and chemoprevention. Although inhibition of the activity of transcription factors or their co-activators is a challenging strategy, recent preclinical and epidemiological evidence suggest new approaches for targeting the YAP/TAZ signal transduction pathway.

Many studies have shown that the mevalonate pathway is markedly up-regulated in several epithelial cancers via mutant p5395, 104, 105 and Akt/mTORC195. Statins are specific inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-methylglutaryl (HMG) CoA reductase106 which is the rate-limiting enzyme in the generation of mevalonate, the first step in the biosynthesis of isoprenoids leading to farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GG-PP) and cholesterol. Transfer of the geranylgeranyl moiety to a COOH-terminal cysteine of Rho GTPases is critical for their function in signal transduction. In turn, active Rho (i.e., Rho-GTP) is essential for YAP/TAZ activation via actin cytoskeletal organization. Statins, which are usually well tolerated and generally safe, are used to treat hypercholesterolemia and prevent cardiovascular diseases. Although initially inconsistent, mounting epidemiological studies indicate that the use of statins is associated with a reduced risk and beneficial effects in PDAC107–111, especially in men110, 111. For example, a recent large study demonstrated that statin use was associated with a 34% reduced risk of PDAC, with a stronger association in male subjects110. In addition to their potential use in primary prevention, statins have also been shown to improve the survival of patients after resection of primary PDAC tumors, indicating a possible role of statins in the prevention of secondary PDAC107, 108, 112. Of great interest, a high-throughput screen of compounds capable of altering the subcellular localization of YAP led to the identification of statins as potential YAP inhibitors via the inhibition of Rho113. An independent study that examined the regulation of the expression of the receptor for hyaluronan-mediated motility (RHAMM) also led to the discovery that statins inhibit YAP/TAZ activity23. Consequently, statins provide a plausible strategy for targeting YAP/TAZ function and thus, an explanation for the mechanism by which these drugs appear to exert beneficial effects in PDAC. In view of these considerations, prospective clinical trials targeting YAP/TAZ with statins in primary or secondary PDAC chemoprevention are needed.

Metformin (1,1-dimethylbiguanide hydrochloride) is the most widely prescribed drug for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) worldwide94, 114. Epidemiological studies suggest that administration of metformin may reduce cancer incidence and mortality in diabetic patients115. A recent meta-analysis indicated that metformin improved survival in PDAC patients with resection and patients with locally advanced tumors, but not in patients with metastatic PDAC116. In mechanistic studies, we demonstrated that metformin potently stimulated AMPK activation in intact human PDAC cells that were cultured with physiological concentrations of glucose in the medium117, 118, and inhibited mTORC1, ERK and mitogenic signaling via AMPK at low concentrations117–119. Metformin also inhibited the growth of PDAC xenografts29, 120 and the development of PanINs and PDAC in KC mice121. As indicated above, AMPK, a well-known sensor of cellular energy94, opposes YAP function via direct phosphorylation of YAP at Ser-94122, 123 as well as by phosphorylation of HMG-CoA reductase at Ser-872, which inhibits mevalonic acid synthesis124. These studies imply a connection between cellular energy status, lipid metabolism, AMPK and YAP/TAZ function. Because statins and metformin interfere with YAP function through different mechanisms, it is plausible that a combination of these agents additively or synergistically may suppress YAP/TAZ activity and thereby exerts cancer-preventive activity at low concentrations of each agent.

As indicated in Fig. 4, YAP/TAZ leads to an increase of the Notch pathway, which is likely to contribute to the oncogenic effects of YAP/TAZ. Indeed, pharmacological inhibitors of Notch activation reduced PDAC xenograft growth in preclinical models125 but were not effective in PDAC patients with advanced disease126. Upstream of YAP, inhibitors of EGFR have already shown a small favorable effect in PDAC127, however, other pathways can bypass EGFR. mTORC1 is part of an amplification loop that leads to YAP expression and enhanced activity, and the heterodimer of TSC2 and TSC1 which opposes mTORC1 signaling100, 101, is associated with a favorable prognosis for patients with PDAC. A number of mTOR inhibitors are available but their efficacy decreases with time and YAP provides one route for escape128. There is a clear need for further studies using combinations of drugs that target the YAP network at different levels to determine their possible anticancer activity.

A number of small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including dasatinib and pazopanib, induce YAP/TAZ phosphorylation and cytoplasmic degradation and reduce their nuclear translocation, suggesting another approach for restraining YAP/TAZ activity129. Although these inhibitors frequently induce drug resistance via enhancement of compensatory pathways130 these tyrosine kinase inhibitors could be considered as part of a combinatorial strategy.

A number of laboratories have searched for compounds that inhibit the nuclear localization of YAP and/or the interaction of YAP with TEAD131. Verteporfin (trade name Visudyne), a member of the porphyrin family, is used in photodynamic therapy of ophthalmological diseases to destroy new abnormal vessels with few side effects. Verteporfin, without light activation, has been reported to inhibit YAP/TEAD complex formation, thereby acting as a suppressor of cell growth132–134. However, in addition to its putative inhibitory effect on YAP/TEAD function, verteporfin also induces protein cross-linking via a non-enzymatic mechanism135, 136. Thus, verteporfin provides a plausible strategy for interfering with YAP/TEAD function within cells, but it has additional cellular effects and therefore its specificity as a YAP/TEAD antagonist has been questioned.

Mammalian Vestigial-like 4 (VGLL4) is a tumor suppressor that does not bind directly to DNA but competes with YAP for binding TEADs137, 138. A peptide capable of mimicking the function of VGLL4 suppressed tumor growth in vitro and in vivo, implying that disrupting the YAP-TEAD interaction by a VGLL4-mimicking peptide may be a therapeutic strategy for inhibiting YAP-mediated cell proliferation137. However, this approach has limitations, including the permeability of the peptide across the plasma membrane and its stability. Importantly, crystal structures of YAP/TEAD139 and TAZ/TEAD140 complexes have been solved, opening new avenues for computational modeling of compounds that disrupt these molecular complexes within intact cells141, 142.

Conclusion and implications

PDAC is generally a fatal disease with no efficacious treatment modalities. It is important that strategies to prevent the disease be explored, especially since its incidence is projected to increase markedly in the next decade. YAP and TAZ, the major downstream targets of the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway (Fig. 1), are also regulated by a multitude of other inputs, including KRAS (Fig. 2). The data discussed in this article indicate that not only YAP (Fig. 3) but also many components of the YAP network are associated with overall survival in PDAC (Fig. 4). Indeed, multiple downstream targets of YAP/TAZ/TEAD are associated with unfavorable survival of PDAC patients. Similarly, multiple components that stimulate YAP activity, including AP-1 which synergizes with YAP (FOSL1) and growth factors (TGFα, EPEG, and HBEGF), GPCRs (P2Y2R, GPR87), a specific integrin (ITGA2) or an inhibitor of the Hippo pathway (MUC1), are all convincingly associated with unfavorable survival in PDAC (Fig. 4). In sharp contrast, increased expression of YAP inhibitory pathways (LKB-1, PKA, TSC) portends a favorable prognosis. All of these associations which have been derived from the recently published interactive open-access database (www.proteinatlas.org/pathology) that allows genome-wide exploration of the impact of individual proteins on survival outcomes, emphasize that increased expression of the YAP signaling web correlates with poorer survival of patients with PDAC. This analysis convincingly supports the notion that the YAP network is a target for therapeutic and preventive strategies in PDAC. The association of patient survival to the YAP/TAZ signaling network strongly suggests a need for novel combinatorial strategies for targeting the YAP network in PDAC, one of the most lethal diseases.

Upstream of YAP, EGFR inhibitors have already shown a small favorable effect in PDAC127, however, other pathways, including other tyrosine kinase receptors, can bypass EGFR and thus stimulate YAP leading to drug resistance. As indicated above, statins and metformin interfere with YAP function through different mechanisms, and recent epidemiological studies indicate that their administration is associated with beneficial effects in PDAC143, 144. Downstream of YAP, inhibitors of NOTCH pathway activation have shown activity in preclinical models, but were not pursued further because they did not exert any response in advanced PDAC patients. Thus, there are drugs, some of which are FDA-approved and in clinical use, that target the YAP network at different levels, thus providing a rationale for designing combinatorial strategies in both preclinical settings and in future clinical trials for PDAC. Furthermore, there are major efforts to develop potent compounds that disrupt YAP/TEAD and TAZ/TEAD molecular complexes within intact cancer cells.

Given the strong correlation of the YAP signaling network with patient survival that is demonstrated in this article, it is conceivable that a combination of these drugs will suppress YAP/TAZ activity synergistically and thereby exert cancer-preventive activity at low concentrations of each agent, a proposition that warrants further experimental, preclinical and clinical work.

Acknowledgements

E.R. is supported by NIH Grants P01CA163200, R01DK100405, and P30DK41301 and by a Department of Veterans Affair Grant 1I01BX001473 and funds from the endowed Ronald S. Hirschberg Chair of Pancreatic Cancer Research. G.E. is supported by P01CA163200 and funds from the Hirschberg Foundation of Pancreatic Cancer Research. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Authors' contributions

E.R. and G.E. developed the concept; E.R. prepared the manuscript; G.E. and J.S.S. edited the manuscript, J.S.S. and E.R. prepared the illustrations. All authors approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Enrique Rozengurt, Phone: +1 310 794 6610, Email: erozengurt@mednet.ucla.edu.

James Sinnett-Smith, Email: jsinnett@mednet.ucla.edu.

Guido Eibl, Email: geibl@mednet.ucla.edu.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. Cancer J. Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, et al. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ying H, et al. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2016;30:355–385. doi: 10.1101/gad.275776.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones S, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biankin AV, et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491:399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant KL, Mancias JD, Kimmelman AC, Der CJ. KRAS: feeding pancreatic cancer proliferation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014;39:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hingorani SR, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hingorani SR, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sudol M, et al. Characterization of the mammalian YAP (Yes-associated Protein) gene and its role in defining a novel protein module, the WW domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:14733–14741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanai F, et al. TAZ: a novel transcriptional co-activator regulated by interactions with 14-3-3 and PDZ domain proteins. EMBO J. 2000;19:6778–6791. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meng Z, Moroishi T, Guan KL. Mechanisms of hippo pathway regulation. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1–17. doi: 10.1101/gad.274027.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santinon G, Pocaterra A, Dupont S. Control of YAP/TAZ activity by metabolic and nutrient-sensing pathways. Trends Cell. Biol. 2016;26:289–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanconato F, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S. YAP/TAZ at the roots of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2016;29:783–803. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moroishi T, Hansen CG, Guan KL. The emerging roles of YAP and TAZ in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2015;15:73–79. doi: 10.1038/nrc3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, et al. Downstream of mutant KRAS, the transcription regulator YAP is essential for neoplastic progression to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra42–ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber R, et al. YAP1 and TAZ control pancreatic cancer initiation in mice by direct up-regulation of JAK–STAT3 signaling. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:526–539. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang S, et al. Active YAP promotes pancreatic cancer cell motility, invasion and tumorigenesis in a mitotic phosphorylation-dependent manner through LPAR3. Oncotarget. 2015;6:36019–36031. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapoor A, et al. Yap1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic Kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2014;158:185–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varelas X. The Hippo pathway effectors TAZ and YAP in development, homeostasis and disease. Development. 2014;141:1614–1626. doi: 10.1242/dev.102376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng Y, et al. Identification of Happyhour/MAP4K as alternative Hpo/Mst-like kinases in the hippo kinase cascade. Dev. Cell. 2015;34:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enzo E, et al. Aerobic glycolysis tunes YAP/TAZ transcriptional activity. EMBO J. 2015;34:1349–1370. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z, et al. Interplay of mevalonate and Hippo pathways regulates RHAMM transcription via YAP to modulate breast cancer cell motility. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E89–E98. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319190110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finch-Edmondson ML, et al. TAZ protein accumulation is negatively regulated by YAP abundance in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:27928–27938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.692285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi H, et al. An imbalance in TAZ and YAP expression in hepatocellular carcinoma confers cancer stem cell–like behaviors contributing to disease progression. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4985–4997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 2013;27:355–371. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Straßburger K, Tiebe M, Pinna F, Breuhahn K, Teleman AA. Insulin/IGF signaling drives cell proliferation in part via Yorkie/YAP. Dev. Biol. 2012;367:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Sinnett-Smith J, Stevens JV, Young SH, Rozengurt E. Biphasic regulation of Yes-associated Protein (YAP) cellular localization, phosphorylation, and activity by G protein-coupled receptor agonists in intestinal epithelial cells: a novel role for protein kinase D (PKD) J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:17988–18005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.711275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kisfalvi K, Eibl G, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Metformin disrupts crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptor and insulin receptor signaling systems and inhibits pancreatic cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6539–6545. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J, Kisfalvi K. Crosstalk between Insulin/Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors and G protein-coupled receptor signaling systems: a novel target for the antidiabetic drug metformin in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:2505–2511. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao F, et al. Insulin receptor and GPCR crosstalk stimulates YAP via PI3K and PKD in pancreatic cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017;15:929–941. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Adhesion to fibronectin regulates Hippo signaling via the FAK–Src–PI3K pathway. J. Cell. Biol. 2015;210:503–515. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan R, Kim NG, Gumbiner BM. Regulation of Hippo pathway by mitogenic growth factors via phosphoinositide 3-kinase and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:2569–2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216462110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rozengurt E, Rey O, Waldron RT. Protein kinase D signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13205–13208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rozengurt E. Protein kinase D signaling: multiple biological functions in health and disease. Physiology. 2011;26:23–33. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00037.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin KC, et al. Regulation of Hippo pathway transcription factor TEAD by p38 MAPK-induced cytoplasmic translocation. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2017;19:996–1002. doi: 10.1038/ncb3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin L, et al. The Hippo effector YAP promotes resistance to RAF- and MEK-targeted cancer therapies. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:250–256. doi: 10.1038/ng.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Agostino S, et al. YAP enhances the pro-proliferative transcriptional activity of mutant p53 proteins. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:188–201. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie D, et al. Hippo transducer TAZ promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition and supports pancreatic cancer progression. Oncotarget. 2015;6:35949–35963. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mello SS, et al. A p53 super-tumor suppressor reveals a tumor suppressive p53-Ptpn14-Yap axis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:460–473.e466. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hong X, et al. Opposing activities of the Ras and Hippo pathways converge on regulation of YAP protein turnover. EMBO J. 2014;33:2447–2457. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strnadel J, et al. eIF5A-PEAK1 signaling regulates YAP1/TAZ protein expression and pancreatic cancer cell growth. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1997–2007. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hansen CG, Ng YLD, Lam WLM, Plouffe SW, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway effectors YAP and TAZ promote cell growth by modulating amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Cell. Res. 2015;25:1299–1313. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang N, et al. Regulation of YAP by mTOR and autophagy reveals a therapeutic target of tuberous sclerosis complex. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:2249–2263. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shao DD, et al. KRAS and YAP1 converge to regulate EMT and tumor survival. Cell. 2014;158:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murakami S, et al. Yes-associated protein mediates immune reprogramming in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2017;36:1232–1244. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang G, et al. Targeting YAP-dependent MDSC infiltration impairs tumor progression. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:80–95. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salcedo Allende MT, et al. Overexpression of Yes associated protein 1, an independent prognostic marker in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, correlated with liver metastasis and poor prognosis. Pancreas. 2017;46:913–920. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uhlen, M. et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science357, eaan2507 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Zanconato F, et al. Genome-wide association between YAP/TAZ/TEAD and AP-1 at enhancers drives oncogenic growth. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2015;17:1218–1227. doi: 10.1038/ncb3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Calvo F, et al. Mechano-transduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodelling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer associated fibroblasts. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2013;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/ncb2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Porazinski S, et al. YAP is essential for tissue tension to ensure vertebrate 3D body shape. Nature. 2015;521:217–221. doi: 10.1038/nature14215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qiao Y, et al. YAP regulates actin dynamics through ARHGAP29 and promotes metastasis. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mizuno T, et al. YAP induces malignant mesothelioma cell proliferation by upregulating transcription of cell cycle-promoting genes. Oncogene. 2012;31:5117–5122. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie Q, et al. YAP/TEAD-mediated transcription controls cellular senescence. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3615–3624. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park HW, et al. Alternative Wnt signaling activates YAP/TAZ. Cell. 2015;162:780–794. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schütte U, et al. Hippo signaling mediates proliferation, invasiveness, and metastatic potential of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Transl. Oncol. 2014;7:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Piao J, et al. Ezrin protein overexpression predicts the poor prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2015;98:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiler SME, et al. Induction of chromosome instability by activation of Yes-associated protein and forkhead box M1 in liver cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:2037–2051. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xin M, et al. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor signaling by Yap governs cardiomyocyte proliferation and embryonic heart size. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:ra70–ra70. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tschaharganeh DF, et al. Yes-associated protein up-regulates Jagged-1 and activates the Notch pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1530–1542.e1512. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ren YR, Patel K, Paun BC, Kern SE. Structural analysis of the cancer-specific promoter in mesothelin and in other genes overexpressed in cancers. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:11960–11969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.193458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu N, et al. The Hippo signaling functions through the Notch signaling to regulate intrahepatic bile duct development in mammals. Lab. Invest. 2017;97:843–853. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2017.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Idichi T, et al. Regulation of actin-binding protein ANLN by antitumor miR-217 inhibits cancer cell aggressiveness in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:53180–53193. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang L, et al. Expression of amphiregulin predicts poor outcome in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2016;11:60. doi: 10.1186/s13000-016-0512-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bachmann K, et al. Cyclin D1 is a strong prognostic factor for survival in pancreatic cancer: analysis of CD G870A polymorphism, FISH and immunohistochemistry. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015;111:316–323. doi: 10.1002/jso.23826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Han Sx, et al. Serum dickkopf-1 is a novel serological biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19907–19917. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vallejo A, et al. An integrative approach unveils FOSL1 as an oncogene vulnerability in KRAS-driven lung and pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14294. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dai J, Yang L, Wang J, Xiao Y, Ruan Q. Prognostic value of FOXM1 in patients with malignant solid tumor: a meta-analysis and system review. Dis. Markers. 2015;2015:352478. doi: 10.1155/2015/352478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Winter JM, et al. A novel survival-based tissue microarray of pancreatic cancer validates MUC1 and mesothelin as biomarkers. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheng XB, Sato N, Kohi S, Koga A, Hirata K. Receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility is associated with poor survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J. Cancer. 2015;6:1093–1098. doi: 10.7150/jca.12990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Itoi T, et al. Ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2 mRNA expression in pretreatment biopsies obtained from unresectable pancreatic carcinomas. J. Gastroenterol. 2007;42:389–394. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma Q, Wu X, Wu J, Liang Z, Liu T. SERP1 is a novel marker of poor prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients via anti-apoptosis and regulating SRPRB/NF-κB axis. Int. J. Oncol. 2017;51:1104–1114. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.4111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang S, Zhang L, Chen X, Chen Y, Dong J. Oncoprotein YAP regulates the spindle checkpoint activation in a mitotic phosphorylation-dependent manner through up-regulation of BubR1. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:6191–6202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.624411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jagannathan R, et al. AJUBA LIM proteins limit hippo activity in proliferating cells by sequestering the hippo core kinase complex in the cytosol. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016;36:2526–2542. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00136-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu H, et al. Silencing IGFBP-2 decreases pancreatic cancer metastasis and enhances chemotherapeutic sensitivity. Oncotarget. 2017;8:61674–61686. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Neesse A, et al. CTGF antagonism with mAb FG-3019 enhances chemotherapy response without increasing drug delivery in murine ductal pancreas cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12325–12330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300415110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wagner M, et al. Transgenic overexpression of amphiregulin induces a mitogenic response selectively in pancreatic duct cells. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1898–1912. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tao L, Xiang D, Xie Y, Bronson RT, Li Z. Induced p53 loss in mouse luminal cells causes clonal expansion and development of mammary tumours. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14431. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wong KF, Liu AM, Hong W, Xu Z, Luk JM. Integrin α2β1 inhibits MST1 kinase phosphorylation and activates Yes-associated protein oncogenic signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:77683–77695. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anakk S, et al. Bile acids activate YAP to promote liver carcinogenesis. Cell Rep. 2013;5:1060–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quan C, Yan Y, Qin Z, Lin Z, Quan T. Ezrin regulates skin fibroblast size/mechanical properties and YAP-dependent proliferation. J. Cell. Commun. Signal. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12079-017-0406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alam M, et al. MUC1-C represses the crumbs complex polarity factor CRB3 and downregulates the hippo pathway. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016;14:1266–1276. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Y, et al. PKC[iota] regulates nuclear YAP1 localization and ovarian cancer tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2017;36:534–545. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rosenbluh J, et al. β-catenin driven cancers require a YAP1 transcriptional complex for survival and tumorigenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1457–1473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tabata Ki, Baba K, Shiraishi A, Ito M, Fujita N. The orphan GPCR GPR87 was deorphanized and shown to be a lysophosphatidic acid receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;363:861–866. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khalafalla FG, et al. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor prompts human cardiac progenitor cell activation by modulating hippo signaling. Circ. Res. 2017;121:1224–1236. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang L, et al. Overexpression of G protein-coupled receptor GPR87 promotes pancreatic cancer aggressiveness and activates NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol. Cancer. 2017;16:61. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0627-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li L, et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinases of the GRK4 protein subfamily phosphorylate inactive G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCRs) J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:10775–10790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.644773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dupont S, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474:179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aragona M, et al. A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Giampietro C, et al. The actin-binding protein EPS8 binds VE-cadherin and modulates YAP localization and signaling. J. Cell. Biol. 2015;211:1177–1192. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Benaud C, et al. AHNAK interaction with the annexin 2/S100A10 complex regulates cell membrane cytoarchitecture. J. Cell. Biol. 2004;164:133–144. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell. Metab. 2005;1:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kuzu OF, Noory MA, Robertson GP. The role of cholesterol in cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:2063–2070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hezel AF, Bardeesy N. LKB1; linking cell structure and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2008;27:6908–6919. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mohseni M, et al. A genetic screen identifies an LKB1/PAR1 signaling axis controlling the Hippo/YAP pathway. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2014;16:108–117. doi: 10.1038/ncb2884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yu FX, et al. Protein kinase A activates the Hippo pathway to modulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1223–1232. doi: 10.1101/gad.219402.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim M, et al. cAMP/PKA signalling reinforces the LATS–YAP pathway to fully suppress YAP in response to actin cytoskeletal changes. EMBO J. 2013;32:1543–1555. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tee AR, et al. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 and -2 gene products function together to inhibit mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-mediated downstream signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:13571–13576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202476899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Garami A, et al. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Y, et al. Rheb is a direct target of the tuberous sclerosis tumour suppressor proteins. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2003;5:578–581. doi: 10.1038/ncb999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Freed-Pastor WilliamA, et al. Mutant p53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via the mevalonate pathway. Cell. 2012;148:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Clendening JW, et al. Dysregulation of the mevalonate pathway promotes transformation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:15051–15056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910258107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science. 2001;292:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1059344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Jeon CY, et al. The association of statin use after cancer diagnosis with survival in pancreatic cancer patients: a SEER-medicare analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0121783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu BU, et al. Impact of statin use on survival in patients undergoing resection for early-stage pancreatic cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1233–1239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chen MJ, et al. Statins and the risk of pancreatic cancer in Type 2 diabetic patients—A population-based cohort study. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;138:594–603. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Walker EJ, Ko AH, Holly EA, Bracci PM. Statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer: results from a large, clinic-based case-control study. Cancer. 2015;121:1287–1294. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carey FJ, et al. The differential effects of statins on the risk of developing pancreatic cancer: a case–control study in two centres in the United Kingdom. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013;58:3308–3312. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2778-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lee HS, et al. Statin use and its impact on survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Medicine. 2016;95:e3607. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sorrentino G, et al. Metabolic control of YAP and TAZ by the mevalonate pathway. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2014;16:357–366. doi: 10.1038/ncb2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Witters LA. The blooming of the French lilac. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:1105–1107. doi: 10.1172/JCI14178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gandini S, et al. Metformin and cancer risk and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis taking into account biases and confounders. Cancer Prev. Res. 2014;7:867–885. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Li X, Li T, Liu Z, Gou S, Wang C. The effect of metformin on survival of patients with pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5825. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06207-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sinnett-Smith J, Kisfalvi K, Kui R, Rozengurt E. Metformin inhibition of mTORC1 activation, DNA synthesis and proliferation in pancreatic cancer cells: dependence on glucose concentration and role of AMPK. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013;430:352–3527. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Soares HP, Ni Y, Kisfalvi K, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Different patterns of Akt and ERK feedback activation in response to rapamycin, active-site mTOR inhibitors and metformin in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ming M, et al. Dose-dependent AMPK-dependent and independent mechanisms of berberine and metformin inhibition of mTORC1, ERK, DNA synthesis and proliferation in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kisfalvi K, Moro A, Sinnett-Smith J, Eibl G, Rozengurt E. Metformin inhibits the growth of human pancreatic cancer xenografts. Pancreas. 2013;42:781–785. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31827aec40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chen K, et al. Metformin suppresses cancer initiation and progression in genetic mouse models of pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2017;16:131. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0701-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mo JS, et al. Cellular energy stress induces AMPK-mediated regulation of YAP and the Hippo pathway. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2015;17:500–510. doi: 10.1038/ncb3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang W, et al. AMPK modulates Hippo pathway activity to regulate energy homeostasis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2015;17:490–499. doi: 10.1038/ncb3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Omkumar RV, Darnay BG, Rodwell VW. Modulation of Syrian hamster 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase activity by phosphorylation. Role of serine 871. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6810–6814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mizuma M, et al. The gamma secretase inhibitor MRK-003 attenuates pancreatic cancer growth in preclinical models. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1999–2009. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.De Jesus-Acosta A, et al. A phase II study of the gamma secretase inhibitor RO4929097 in patients with previously treated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Invest. New. Drugs. 2014;32:739–745. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0083-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ko AH, et al. A multicenter, open-label phase II clinical trial of combined MEK plus EGFR inhibition for chemotherapy-refractory advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016;22:61–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Muranen T, et al. ERK and p38 MAPK activities determine sensitivity to PI3K/mTOR inhibition via regulation of MYC and YAP. Cancer Res. 2016;76:7168–7180. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Oku Y, et al. Small molecules inhibiting the nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ for chemotherapeutics and chemosensitizers against breast cancers. FEBS Open Bio. 2015;5:542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.fob.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Rozengurt E, Soares HP, Sinnet-Smith J. Suppression of feedback loops mediated by PI3K/mTOR induces multiple overactivation of compensatory pathways: an unintended consequence leading to drug resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2477–2488. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Santucci M, et al. The Hippo pathway and YAP/TAZ–TEAD protein–protein interaction as targets for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:4857–4873. doi: 10.1021/jm501615v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Liu-Chittenden Y, et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD–YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1300–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Perra A, et al. YAP activation is an early event and a potential therapeutic target in liver cancer development. J. Hepatol. 2014;61:1088–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Al-Moujahed A, et al. Verteporfin inhibits growth of human glioma in vitro without light activation. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:7602. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07632-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Konstantinou EK, et al. Verteporfin-induced formation of protein cross-linked oligomers and high molecular weight complexes is mediated by light and leads to cell toxicity. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:46581. doi: 10.1038/srep46581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 136.Zhang H, et al. Tumor-selective proteotoxicity of verteporfin inhibits colon cancer progression independently of YAP1() Sci. Signal. 2015;8:ra98–ra98. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aac5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Jiao S, et al. A peptide mimicking VGLL4 function acts as a YAP antagonist therapy against gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:166–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhang Y, et al. VGLL4 selectively represses YAP-dependent gene induction and tumorigenic phenotypes in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:6190. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06227-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Li Z, et al. Structural insights into the YAP and TEAD complex. Genes Dev. 2010;24:235–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.1865810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kaan HYK, et al. Crystal structure of TAZ-TEAD complex reveals a distinct interaction mode from that of YAP–TEAD complex. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:2035. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kaan HYK, Sim AYL, Tan SKJ, Verma C, Song H. Targeting YAP/TAZ-TEAD protein-protein interactions using fragment-based and computational modeling approaches. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0178381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Pobbati AV, et al. Targeting the central pocket in human transcription factor TEAD as a potential cancer therapeutic strategy. Structure. 2015;23:2076–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Amin S, et al. Metformin improves survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and pre-existing diabetes: a propensity score analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1350–1357. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mei Z, et al. Effects of statins on cancer mortality and progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95 cohorts including 1,111,407 individuals. Int. J. Cancer. 2017;140:1068–1081. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]