Abstract

Health care disparities are a well-documented concern among patients and providers who care for minority groups in the United States. In this study, focus groups were created from an original sample of 606 Black women representing three regions in the United States: the South, the Midwest, and the Virgin Islands. Composed of 10 randomly selected members each (n = 30), the focus groups provided insights into the nature of these disparities, with some suggestions for viable solutions. Participants voiced concerns about cultural taboos about discussing menopause, financial concerns, and negative experiences with health care leading to distrust in medical systems. The primary solution proposed was an increase in Black health care professionals who would have increased rapport with, empathy for, and understanding of the concerns of Black women.

Keywords: Black women, health disparities, Medicaid/Medicare, poverty, quality of care

Introduction to Disparities in Healthcare

Across most disease conditions, Black women experience more health disparities than their White counterparts. They report higher levels of stress, poverty, and marginalization (Benjamins, 2013; Dammann & Smith, 2011; Dolezsar, McGrath, Herzig, & Miller, 2014; Mathunjwa-Dlamini, Gary, Yarandi, & Mathunjwa, 2011). To appropriately assist them with accessing and using available healthcare services, researchers and practitioners must seek to better understand the experiences of Black women and determine their perceived barriers to quality health services. The elimination of health disparities among Black and other vulnerable populations will necessitate prompt and efficient diagnoses, the correct preventive and lifesaving evidence-based interventions administered in a prompt and efficient manner, and the precise administration of pharma-therapeutic medications and treatments. Of equal significance are the interactions among health care providers, the patient and family members. Listing to patients and family members, interacting with respect, and responding to their questions and concerns in a culturally and linguistically sensitive manner, are a few of the cornerstones that are linked to improving the health status of Black women, and all others in the nation (Agency for Healthcare Research, 2012).

The data in this research were derived from focus group discussions; the members of these groups represented three regions in the United States: the South, the Midwest, and the Virgin Islands. Each group consisted of 10 women (n = 30), ranging from 40 to 60 years of age, who had been randomly selected from a sample of 606 women who, for a previous study, had volunteered to participate in face-to-face individual interviews with nurse researchers. The researchers identified three recurring themes from the focus group data: (a) cultural taboos about discussing menopause, (b) financial concerns, and (c) negative experiences with health care leading to distrust in medical systems. Additional sub-categories emerged when participants discussed their previous experiences with healthcare and health care providers.

In general, the women had difficulty understanding medical terms that were used to “inform them” about their health, yet they expressed reluctance to ask health care professionals for clarification. Hence, communications between the provider and the patient were strained and seldom effective. The providers at the clinics frequented by these women were neither ethnically nor racially diverse, which may have hindered open communications and served as barriers to facilitating a culturally and linguistically clinical encounter (Koh, Gracia, & Alvarez, 2014; Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003).

Significance

Health disparities among Blacks have been well documented. According to the 2010 US population survey, more Black women live in poverty than do women of any other racial background including Whites, Asians, and Hispanics (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Black people have the highest rate of morbidity and mortality which is a result of living in poverty, experiencing prejudice and discrimination, enduring continuous stress, sexism, and racism in interactions across several societal institutions, including health care systems (Basu, 2009; Shah, Mullainathan, & Shafir, 2012; Stevens-Watkins, Perry, Pullen, Jewell, & Oser, 2014). Black women who live in poverty generally suffer the consequences of inadequate education, limited nutritional resources, and restricted health care options, and many of them work as nonprofessionals and in stressful environments (Muhammad, 2011; Perry et al., 2013). They often live in under-resourced neighborhoods where safety concerns abound, and the availability of other health-facilitating resources such as adequate neighborhood food stores, parks, and recreational options are inadequate (Quillian, 2012; Smedley et al., 2003). Numerous studies have confirmed that women experience disparities based on ethnicity. In their research, Ajrouch, Reisine, Lim, Sohn, and Ismail (2010) demonstrated that Black women experience more physiological and psychological stress than do women from other racial groups. Gibbons et al. (2014), Jagannathan, Camasso, and Sambamoorthi (2010), and Maddox (2013) all concurred that stress and poor health status are higher among Black women than among their counterparts from all other ethnic/racial backgrounds.

Methods

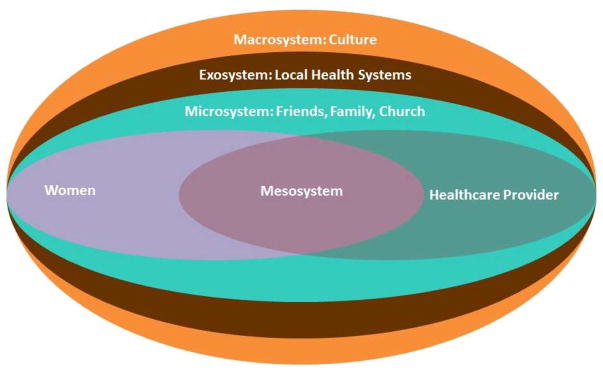

The Ecological Model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) was used to guide this research. The model proposed that five levels of a system interact to generate an environment that impacts the lives of people, their families and communities. The ontogenic (individual) development; the microsystem (family, friends, and church); the mesosystem (combined effects of microsystem and exosystem); the exosystem (community); and the macrosystem (cultural influences; see Figure 1).The ecological systems theory provides a useful approach for unraveling the many systems layers that impact the health status and well-being of Black women, and the culture within which they live. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at three universities: Case Western Reserve University (Ohio), University of Florida (Florida), and the University of the Virgin Islands (Virgin Islands). The demographic data were derived from studies originally conducted in the rural Southern United States (n = 206), the urban Midwest (n = 200), and the Virgin Islands (n = 200), consisting of Black women ranging from 40 to 60 years of age (Mathunjwa-Dlamini et al., 2011). For this study, focus group participants were randomly selected from the initial group of 606 based on location; discussions during the focus groups (representing rural Southern, urban Midwest, and Virgin Islands with 10 women in each group; n = 30) were recorded by the researchers who used three tape recorders to help assure that we had accurately and completely recorded the data.

Figure 1.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model modified for study of women and the healthcare system. Adapted from “The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design,” by U. Bronfenbrenner, 1979. Copyright 1979 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Each focus group lasted for 90 minutes at which time the same set of six questions were presented to the women by the lead researcher who was assisted by two other moderators. At each of the three settings, one or two of the moderators were indigenous to the geographical. Our sensitivity to cultural and language nuances, health beliefs and practices, was evidenced by this approach, which served to be useful. In addition, special attention was given to the group process and special efforts were made to help assure that all of the women had an adequate chance to express their thoughts and feelings. We necessary, the moderators probed, asked questions that would help to clarify the topic. At times, the moderators would ask the women to provide examples.

We prepared for data analysis by independently reviewing the transcribed focus group data no fewer than three times. Each researcher generated code/themes that were referenced to quotations, the specific narratives in the texts. The analyses was conducted in three phases. In phase one, the data were clustered under the six research questions. Phase two included the integration of other codes that might not have been integrated under the six questions, but was of significance to the women as determined by the researchers who continued to read and re-read the transcribed data. The third phase was primarily focused on validation and confirmation of the accuracy and appropriate coding of the data. When there were questions about codes and quotations, the researchers independently reviewed the data and then engaged in a discussion until the concerns were resolved as dictated by the data (Richards, 2005).

Each participant was compensated $20 for her time, and the groups were conducted at locations in the women’s communities in Florida, Ohio, and the Virgin Islands such as a library, a community center, or a nearby university. Six health-related questions aimed at learning about participants’ knowledge of menopause, self-care, stress, depression, and other health-related behaviors guided discussion in the focus groups. Despite these structured questions, the researchers recognized several prominent themes that were generated from the data and are reported in this research.

How would you describe your general health?

What barriers do you face when trying to receive health care?

What is your knowledge about menopause?

How do you manage menopause?

How do you deal with stress and its related consequences?

How can you improve your health?

Results

The researchers identified several recurring themes that emerged from the focus groups, and these were categorized as (a) cultural taboos about discussing menopause, (b) financial concerns, and (c) negative experiences with health care leading to distrust in medical systems. In practice, these themes were manifested by fear of being rejected by the healthcare providers; discomfort when discussing menopause; flawed communications; and provider-patient conflicts about health practices and beliefs. Participants reported lack of guidance, interactions influenced by racial bias, observations of providers’ work-related stress, and financial issues as significant barriers to health. Although the women often did not fully grasp providers’ recommendations, they were reluctant to ask questions. Participants believed that communication would be enhanced if their health care providers were also Black, and that better communication would improve healthcare overall. Several participants emphasized the importance of family support and spiritual aspects for Black patients.

Themes Reflecting Barriers to Healthcare

Barriers to health care were embedded in the narratives from the three focus groups, and three clear themes emerged: (a) cultural taboos about discussing menopause, (b) financial concerns, and (c) negative experiences with health care leading to distrust in medical systems. Researchers reviewed the narratives, and grouped responses into the categories. These themes are discussed in the following sections.

Cultural Taboos About Discussing Menopause

Several of the participants reported lack of communication and guidance from their mothers or caregivers. Their accounts suggested that topics related to women’s reproductive health were inappropriate to discuss with others. This led to ignorance about those health issues that are a natural part of every woman’s life; consequently, some women in the focus groups experienced needless anxiety over normal life changes. The following exchange illustrates the prevalence of a void in mother-daughter communications regarding menopause:

I don’t remember my Mama talking about this [menopause].

I don’t remember my Mama talking about it [menopause] either.

The lack of communication from mothers to daughters about women’s health concerns carried over into adulthood, as observed in the discomfort the women felt when talking about such issues in the focus groups. The women avoided using the term menopause, instead opting for this or it, as seen in the above quotations. There was greater comfort with the use of colloquialisms (e.g., on-the-change): “[My mother never discussed] mood swings, tired feelings, depression, on-the-change.” The participants felt a general awkwardness when talking about menopause; some laughed uncomfortably and others shifted frequently in their seats. Participants seemed unsure how to go about voicing their concerns, indicating that the mother’s discomfort with female health issues had been passed on to the next generation.

Financial Issues: Health Insurance and Other Resources

Among each of the groups, there was considerable discussion about the influence of financial issues on the quality of care received. Almost all participants shared the view that quality of care was directly related to the type of insurance one has, with most participants having had firsthand experience with Medicare and Medicaid. A repeatedly voiced concern was that Medicare and Medicaid recipients are often individuals who struggle to get by on restricted incomes, leaving limited resources for extra expenses, such as transportation to medical appointments and medical expenses that are not covered by insurance.

With advancing age, there is an increased likelihood of having medical conditions that require services that go beyond the expertise of general practitioners, necessitating referrals to specialists; the recipients often perceived such referrals as being given the “run-around,” just one consequence of a shaky foundation of trust.

The system is all screwed up as far as the funding; the older people, they may have worked all their years and now they’re on Social Security and Medicare but still, it’s not enough because that money isn’t designated there for them. Doctors give them the run around because they’re older, so by the time those people have to go three or four places, they’re out of gas, they just can’t go anymore.

Other participants shared that ability to pay for healthcare affects the way providers handle patients, and ultimately affects whether individuals seek care in a timely fashion. There was considerable disillusionment with Medicaid/Medicare benefits. Participants mentioned that hospitalized Medicaid/Medicare recipients experienced lower quality care and a more hostile environment compared to that enjoyed by “paying” hospitalized patients.

On Medicaid/Medicare? They’re not really concerned about you. They put you off in the other end of the hospital over there because that’s what they [Medicaid and Medicare] pay for. They don’t pay for you to be in the big part of the hospital where the other people are; there’s a special place where they put you if you’re on Medicaid, Medicare, you know.

We have a lot of them [patients] that don’t have insurance, and they’re scared to come to a hospital where they can get treatment and stuff because they don’t have insurance.

And something else too, with the Medicaid/Medicare, you got a lot of them up there now saying, “Well we don’t take Medicaid/Medicare.”

To me it’s more of a money thing than anything.

Yeah, and I think it all boils down to money because I think that doctors, that they’re not really concerned you know, about the patients. Like the ones that are on Medicaid and stuff like that; they sweep us through like that [snaps fingers].

Group participants pointed out that the problem went beyond health insurance, implying that health care for Black women was inadequate independent of payer:

Well, they do us like that too. I have good insurance, and I have still had problems with doctors.

Whether you are Medicare, Medicaid, or totally financially able, you want a service, and you want to be treated that way [with concern and respect].

Other participants commented that health insurance has its own limits due to inadequate coverage for the necessities that support quality of care.

But you know it’s the way that the system works. When you don’t have money, it is [a problem]. And a lot of older people are not getting the care they need to because a lot of them are on Medicaid [or] Medicare, and Medicare doesn’t really pay anything. Say for instance, I was old and I need a chair, a wheelchair. Well, if Medicare doesn’t cover that chair, [or if they only cover] up to a certain amount, then I can’t get it.

As the above comments elucidate, insurance concerns were at the forefront of many focus group participants’ minds. Medicaid/Medicare was a recurring theme; repeated references were made to the dilemma of living on a fixed income and having medical expenses that were not covered by insurance, whether private insurance or Medicaid/Medicare. Furthermore, Medicaid and Medicare were perceived to be stigmatizing, resulting in substandard treatment in health care facilities.

In addition to concerns about paying for direct health care services, participants voiced concern about deficits with other resources. These included finding transportation to and from appointments; managing basics like hygiene; navigating inaccessible parking, curbs, doorways, and stairs; self-advocacy when dealing with healthcare providers; budgeting; and finding assistance with procuring needed goods and services. One participant addressed this broader issue, remarking that some healthcare difficulties arose from the lack of family or community support to assist in the logistics of getting from home to the clinic.

They (patients) do get sicker because they can’t go or they don’t have other people to take them to get them to where they need to go.

Negative Experiences with Healthcare Systems and Health Care Providers

Almost all participants indicated that they themselves or someone in their community had had a negative experience with health care delivery. We categorized these experiences as (a) unsatisfactory interactions with health care providers, (b) confidentiality concerns, (c) being excluded from a plan of care and/or having information withheld from them, (d) fear of retribution, (e) observing unprofessional behavior, and (f) receiving inferior care because of race.

Unsatisfactory interactions with health care providers

Providers’ disengagement and a sense of non-caring surfaced in the group discussions. Some doctors never touched their patients. The women had intense emotional reactions, reporting that they have been routinely treated like untouchables. This troublesome non-verbal communication, in which the doctor or nurse seemed to avoid touching the patient, was problematic when the patient had initiated the visit due to major concerns about injuries or illness and left feeling that the doctor had not conducted a thorough, hands-on examination. The women concurred that, in these situations, it was particularly difficult to follow the recommendations of the doctor because they believed the doctor was not making suggestions with complete information.

When the doctor come in he’d cross his leg, and say “How you doing; you doing fine? Well, is there anything bothering you?” “Well,” I’d say, “my back is still bothering me.” He’d say, “Well, it’ll get better. Sign this paper. Take this.” That doctor did not put his hands on me. Never touched me!

Unwillingness to touch a patient created an air of unpleasantness with undertones of racial stereotyping. The unspoken message was that the patient was subhuman, revolting, or contaminated in some way.

Some of them [doctors] look at you like you crazy. They don’t even speak.

They (doctors) are not interested, you have to tell them.

Doctors just look at you and say, “Well, I don’t see anything wrong with you.” And then you just walk away. Why I would want to go to them if they’re not going to do anything for me?

The resulting care was considered to be inadequate, and the patient’s health status likely did not improve. Part of the problem, according to some of the women, was due to the minimal amount of time doctors and nurses spent caring for their patients.

They only keep them [patients] like two days in there, you know that? Say, ok then, everything has been taken care of in two days. Two weeks later, she [mother of the participant] was back again with the same problem. Well, how can you take good care of a person when they only have like two days in there and the doctor runs in there and runs out?

They (doctors) don’t take the time to find out [about your problem].

The moderator attempted to clarify the lack of interest in Black female patients’ concerns by asking, “So you think they [health care providers] don’t know or they don’t take the time to find out [about patients’ needs]?” The women exclaimed in unison, “They don’t take the time to find out!” “They’re not interested!” “You have to tell them!”

A few of women recognized that sometimes what could be perceived as disinterest actually arose from the way patients were scheduled in the clinic, which placed severe limits on the amount of time a doctor could devote to each patient.

They schedule four or five people for the same time, and that is not what we need. We need them to at least talk with us; they get you, and then you’re out of there in fifteen minutes.

Just like you said, the doctors don’t sit down and talk to them [patients] face-to-face.

Confidentiality concerns

Several participants feared or had experienced breaches of confidentiality. Indiscretion by providers and staff can have far-reaching consequences socially and economically, especially in small communities in which ethical practices may be difficult to enforce among all staff members.

Another, I guess another situation too—it’s a small community and people think that their confidences are not kept.

Confidentiality? People look at your record—they call their friends. People violate confidentiality: “Blah, blah”—[they go talking about] your business all in the streets.

Well, the doctor wrote ‘bipolar’ on my chart and somebody told my job—that pissed me off!

They were afraid of discussing their health concerns with their providers because of the potential consequences of private information being divulged.

Exclusion

Many participants expressed frustration about feeling left out of the information loop, both for their own care and for the care of loved ones. Some participants commented that doctors never discussed their observations. Not only does this present a serious block in the communication process, it decreases patients’ likelihood of seeking health services in the future or adhering to a proposed treatment plan.

Some doctors don’t even tell you [what your diagnosis is]. You get your mood swings, and you’re thinking, “Oh I’ll go through it.” But medicine is out there that’s helping these other people [White women], and we’re sitting here [enduring the pain] alone.

Concerns were expressed that some health care professionals do not encourage patient input into the plan of care, which participants perceived as providers’ implicit belief that the patient was inferior, incompetent, or too ignorant to comprehend.

I went to the doctor [and] I said, “I got this lump. [It’s been there] about six months.” He said, “Why did you wait so long?” [I responded,] “Well, I’m going to tell you—I can’t have no surgery.” He said, “Well you don’t tell me what to do. I’m the doctor; I’m going to make all these decisions for you.”

In addition to being excluded from or having information withheld about their own care, participants also described negative experiences when trying to help sick relatives. Many women felt that health care providers perceived them as nuisances at best when they tried to advocate for loved ones, and providers refused to adequately explain the health problems of and plans of care for their family members.

You know, some of them [doctors and nurses] won’t tell you the things that you really need to know. When family members act as advocates for their ill relative, tensions often develop.

Many felt they were not being listened to compassionately, and even when a doctor or nurse listened, the women felt they were not being understood.

Fear of retribution

Problems develop when patients are reluctant to voice concerns themselves, yet are more worried about consequences if their family or friends voice concerns in their behalf. Retribution is greatly feared by those who are in vulnerable positions as patients who depend on staff for essential and appropriate care. Silence becomes a coping strategy to avoid maltreatment by healthcare professionals—especially by nursing staff who provide continuous care.

And then I’ve heard a lot of patients say [that they tell their friends and relatives], “Hey, don’t say nothing [about poor care being received in the hospital], don’t say nothing ‘cause, you know, I’ve got to stay in here when you leave and they [the hospital staff] might mistreat me.” And I say, “They better not mistreat you! You’re the patient; you’re not supposed to be mistreated.” But they’re afraid they’ll be mistreated or somebody will do something vengeful against them and they say, “Don’t say nothing!”

A woman related an unpleasant situation that occurred in the hospital when her brother spoke up for the needs of another patient who shared the same hospital room as their father. She felt that the man in the adjoining bed to her father would have been shamefully neglected had her brother not spoken up. Unfortunately, she relates, her brother was rebuffed for his concern; their father was put in a separate room where the staff’s inattentiveness would be less likely to be observed.

They [the hospital staff] said we were making trouble…they moved him [father of participant] into a room by himself. Other patients may also need help. Well, my brother had to tell the lady [nurse] that she needed to clean up the man next to him because they had left him in it [soiled sheets], and it was another Black man.

Unprofessional behavior

Some participants emphasized that work-related stress in the hospital environment may be one of the factors that prevented Blacks from receiving quality care. They observed that stressful and strained interactions among the providers themselves, along with the continuous demands associated with patient care, contribute to inadequate treatment for Blacks.

Some of the nurses get mad with the doctor for hollering at them or something and then the nurses want to take it out on the patients or something, I don’t know.

‘Cause they [Blacks] don’t trust people, and you see why. You know because you’re Black you think, “Ok, they [providers] don’t understand, they don’t listen to you.” You don’t trust them and, you know, if you hear somebody talking about you, you know, this is supposed to be the nurse. You know she shouldn’t be talking about you; she should be your advocate. She should be speaking up for you. And if she’s not, then who do you have speaking for you if you don’t have your family?

Receiving inferior care because of race

Many participants’ comments directly or indirectly indicated concerns about the quality of their health care being influenced by providers’ attitudes about race.

The nurse calls to see if I am okay. They [my healthcare providers] know me—they care about me—and my children. [The nurse] said, “Now you call me whenever you need me.” [The nurse] touch me—hugged me one time. Speaks to me in the streets. Gives me good medicine—not that cheap kind.

Interestingly, the reference to the cheap kind (i.e., generic medications) suggested that the women perceived these medications to be inferior to brand name medications. Thus, many participants perceived prescriptions for generic medications to undermine their dignity and worth, and to be an underhanded way for providers to offer inferior care because they were Black.

Another woman described her experiences with public health clinics and the attitudes and behaviors of staff at these clinics. Public health clinics bear the stigma of being the health care choice of last resort, used primarily by unstable, undesirable people.

Yeah, they turn up their nose at you, like they don’t want to touch you ‘cause you go to some of these [public health] clinics. Some of them look at you like you’re crazy, like you might have AIDS or something. You got to tell them all, “Hey, I don’t have no AIDS; you can touch me! Touch me!”

Racial stereotyping, in this case, was evidenced by the assumption that all Blacks are potential AIDS-carriers and untouchable. Effective communication with the patient was blocked.

Another woman described feeling like her providers treated her differently during admission because she happened to come alone that day.

They assume because you may be older and you got gray hair or you’re elderly and you’re alone at the time when you’re admitted, that you don’t have family or friends. That’s with Black people. They just assume all these things.

Solutions Proposed by Participants

In all focus groups, the participants indicated that there was a serious need for more Black health providers who could better understand the needs and concerns of Black women. One woman observed that a common background would facilitate communication immensely.

We [Black women] have many health problems that are not being addressed. We need more minority providers. I think you will get the right information when you get the right people talking to you. The surveys and things is not always accurate for Black women.

Other women emphasized the importance of shopping around for the right doctor—one who is willing and able to develop rapport with the patient; this was repeatedly reaffirmed by the women in all focus groups.

You have to be assertive. You have to leave doctors.

You need to shop for doctors like you do for your food.

It gets to a point where you have to care about yourself; you really have to basically want to take care of yourself.

Summary and Solutions

The Black women in the focus groups from the South, Midwest, and United States Virgin Islands have provided rich insights into the nature of the healthcare disparities they have experienced. Their primary concerns revolved around cultural taboos about discussing menopause, financial issues, and negative experiences with health care. They described frustrated attempts at communication on many fronts, beginning with their own mothers and ending with healthcare professionals. Early discomfort with discussing women’s health issues combined with later perceptions of racial prejudice from health care providers translated into barriers to open and frank discussions about treatment options. The participants also believed the quality of their care was affected by payee: insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. Across the three regions, they were united in a general distrust of the healthcare system.

The primary solution proposed and repeated across all focus groups was the need for an increase in Black healthcare professionals who would have increased rapport with, empathy for, and understanding of the concerns of Black women. Additional recommendations gleaned from this research were (a) making health care more affordable, available, and accessible for all people, (b) emphasizing cultural competence as a primary and essential component of health care, (c) improving communication skills of health professionals, and (d) humanizing systems of health care delivery for all people. In addition, we have provided two recommendations that are gleaned from this research, and grounded in the landmark study by the Institute of Medicine in the book, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare (Smedley et al., 2003) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (Koh et al., 2014):

Bias, stereotyping, prejudice, and clinical uncertainty when manifested by healthcare professionals may be a major contributing factor to poor health outcomes among Black women and other minority groups. If patient-provider funded program, along with ethnic/racial diversity among health professionals, perhaps relationship consistency and provider-patient trust would increase, and communications would be strengthened.

The Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services provides a series of 14 essentials that are related to improving healthcare through the implementation of these standards. The standards were designed to address healthcare organizations and systems, but they are equally useful for independent practitioners. By placing emphasis on the culture and language, the standards, when implemented, are intended to the quality of care for all people, including Black women (Koh et al., 2014; Smedley et al., 2003).

References

- Ajrouch KJ, Reisine S, Lim S, Sohn W, Ismail A. Situational stressors among African-American women living in low-income urban areas: The role of social support. Women & Health. 2010;50(2):159–175. doi: 10.1080/03630241003705045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu R. High ambient temperature and mortality: A review of epidemiologic studies from 2001 to 2008. Environmental Health. 2009;8(40):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR. Comparing measures of racial/ethnic discrimination, coping, and associations with health-related outcomes in a diverse sample. Journal of Urban Health. 2013;90(5):832–848. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9787-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dammann KW, Smith C. Food-related environmental, behavioral, and personal factors associated with body mass index among urban, low-income African-American, American Indian, and Caucasian women. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2011;25(6):e1–e10. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.091222-QUAN-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Disparities in health care quality among minority women: Findings from the 2011 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports. 2012 Oct; (AHRQ Publication No. 12-0006-3-EF). Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/nhqrdr11/nhqrminoritywomen11.htm.

- Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJ, Miller SB. Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: A comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychology. 2014;33(1):20–34. doi: 10.1037/a0033718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Kingsbury JH, Weng CY, Gerrard M, Cutrona C, Wills TA, Stock M. Effects of perceived racial discrimination on health status and health behavior: A differential mediation hypothesis. Health Psychology. 2014;33(1):11–19. doi: 10.1037/a0033857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannathan R, Camasso MJ, Sambamoorthi U. Experimental evidence of welfare reform impact on clinical anxiety and depression levels among poor women. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(1):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh HK, Gracia JN, Alvarez ME. Culturally and linguistically appropriate services–Advancing health with CLAS. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(3):198–201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1404321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathunjwa-Dlamini TR, Gary FA, Yarandi HA, Mathunjwa MD. Personal characteristics and health status among southern rural African-American menopausal women. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association. 2011;22(2):59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox T. Professional women’s well-being: The role of discrimination and occupational characteristics. Women & Health. 2013;53(7):706–729. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2013.822455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad RD. Separate and unsanitary: African american women railroad car cleaners and the women’s service section, 1918–1920. Journal of Women’s History. 2011;23(2):87–111. doi: 10.1353/jowh.2011.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillian L. Segregation and poverty concentration: The role of three segregations. American Sociological Review. 2012;77(3):354. doi: 10.1177/0003122412447793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards L. Handling qualitative data: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shah AK, Mullainathan S, Sharif E. Some consequences of having too little. Science. 2012;338(6107):682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1222426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, D.C: The National Academics Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Watkins D, Perry B, Pullen E, Jewell J, Oser CB. Examining the associations of racism, sexism, and stressful life events on psychological distress among african-american women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20(4):561–569. doi: 10.1037/a0036700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. People below poverty level by selected characteristics: 2009 (Table 713) 2012 Retrieved on January 3, 2013 from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0712.pdf.