To the Editor:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a prevalent condition in children and is associated with a significant constellation of morbidities, including neurocognitive, cardiovascular, and metabolic dysfunction (1–3). Activation and propagation of multiple inflammatory pathways, altered lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress mechanisms have all been implicated in end-organ morbidity (4, 5). In two recent papers, Lim and Pack and our group have proposed that disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) may underlie the cognitive impairments associated with OSA (6, 7). As corroborative evidence, studies in mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia have shown increases in brain parenchymal water, along with alterations in aquaporin expression, indicating increased BBB permeability (8, 9). BBB permeability changes have also been inferred in adult patients with OSA (10). In this setting, it has been reported that endothelial cells secrete exosomes, and several reports show that endothelial cells can also be targeted by exosomes derived from different cell types. The tight junction complex is critically involved in the exchange of ions, solutes, and cells that travel across BBB paracellular spaces and tight junctions. Zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) is one of several protein families that are essential for tight junction formation (11), and it is now established that stressful conditions can disrupt brain endothelial tight junctions and affect cognition via exosome-related biological activities affecting the BBB (12).

To examine the potential contribution of circulating exosomes to BBB disruption in the context of pediatric OSA, we explored, using an in vitro BBB system (13), the effect of plasma-derived exosomes from children with polysomnographically determined OSA with evidence of neurocognitive deficits (NC+; n = 12); age-, sex-, ethnicity-, body mass index z-score–, apnea–hypopnea index–matched children with OSA and no evidence of cognitive deficits (NC−; n = 12); and control children without OSA or cognitive deficits (CO; n = 6). The characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 1. All subjects underwent overnight polysomnography, which was scored as per current American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines, and in the morning after the sleep study, fasting blood was drawn into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes, and plasma was immediately separated by centrifugation and stored until assay, immediately followed by cognitive test batteries (1). The presence of cognitive deficits (NC+) was defined as the presence of two or more cluster subtests that were more than 1 SD below the mean, as previously described (14). Plasma exosomes were isolated and purified as previously described (2) and fulfilled all the required criteria as specified by the current consensus of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (15).

Table 1.

Demographic and Polysomnographic Findings among Children with OSA with and without Cognitive Deficits and Control Subjects

| OSA–NC+ (n = 12) | OSA–NC− (n = 12) | CO (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 6.5 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 6.3 ± 1.7 |

| Sex, male, % | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Ethnicity, African American, % | 66.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| Body mass index z-score | 1.04 ± 0.26 | 1.06 ± 0.25 | 1.02 ± 0.29 |

| Total sleep duration, min | 478.8 ± 67.1 | 474.2 ± 66.3 | 473.2 ± 75.1 |

| Stage 1, % | 7.0 ± 3.8 | 7.2 ± 4.1 | 4.8 ± 3.7 |

| Stage 2, % | 40.1 ± 8.8 | 38.6 ± 8.9 | 35.4 ± 9.5 |

| Stage 3, % | 35.5 ± 12.8 | 37.1 ± 11.4 | 41.6 ± 14.2 |

| REM sleep, % | 18.2 ± 8.1 | 17.9 ± 9.5 | 20.2 ± 10.2 |

| Sleep latency, min | 22.4 ± 15.6 | 20.7 ± 13.9 | 24.6 ± 15.2 |

| REM latency, min | 117.7 ± 49.5 | 119.5 ± 52.4 | 118.7 ± 67.4 |

| Total arousal index, events/h of TST | 22.8 ± 11.4 | 20.9 ± 10.3 | 12.5 ± 8.6* |

| Respiratory arousal index, events/h of TST | 7.9 ± 4.2 | 8.2 ± 4.7 | 0.4 ± 0.2* |

| Obstructive apnea–hypopnea index, events/h of TST | 19.9 ± 7.1 | 19.4 ± 6.9 | 0.5 ± 0.3* |

| SpO2 nadir, % | 80.3 ± 8.6 | 82.1 ± 9.0 | 94.1 ± 1.3* |

| ODI3% | 18.4 ± 7.7 | 19.0 ± 8.4 | 0.4 ± 0.2* |

| NEPSY cognitive test battery | |||

| Design copying | 9.07 ± 3.89 (2) | 9.69 ± 3.97 (0) | 9.88 ± 4.22 |

| Phonological processing | 8.26 ± 3.75 (8) | 9.16 ± 3.94 (2) | 9.66 ± 4.17 |

| Tower | 9.48 ± 3.92 (7) | 11.01 ± 3.76 (0) | 11.16 ± 4.56 |

| Speed naming | 8.44 ± 3.65 (8) | 9.22 ± 3.83 (1) | 9.96 ± 4.58 |

| Arrows | 8.37 ± 3.87 (5) | 10.22 ± 3.67 (0) | 11.66 ± 3.84 |

| Visual attention | 10.16 ± 3.53 (1) | 10.47 ± 3.89 (0) | 10.76 ± 3.87 |

| Comprehension | 9.43 ± 3.78 (3) | 10.72 ± 3.66 (0) | 10.96 ± 4.04 |

| Differential Ability Scales | |||

| Verbal | 92.18 ± 14.88 (9) | 97.88 ± 15.61 (1) | 100.25 ± 17.37 |

| Nonverbal | 95.63 ± 12.88 (5) | 100.08 ± 15.12 (1) | 103.55 ± 17.31 |

| Global | 93.91 ± 11.93 (8) | 99.23 ± 15.32 (1) | 102.82 ± 16.14 |

Definition of abbreviations: CO = control subjects; NC+ = with neurocognitive deficits; NC− = without neurocognitive deficits; NEPSY = Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment; ODI3% = oxyhemoglobin desaturation index 3%; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; SpO2 = oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry; TST = total sleep time.

All data are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. For NEPSY cognitive tests and Differential Ability Scales, the number of children who had test performance at least 1 SD below the mean is shown in parentheses.

OSA versus CO (P < 0.001).

Using an immortalized human brain microvascular endothelial cell model (hCMEC/D3; Cat# SCC066, EMD Millipore), the effects of equivalent numbers of exosomes from each subject on transcellular electrical impedance of a hCMEC/D3 monolayer were evaluated by electric cell-substrate impedance-sensing arrays. As previously described (2), exosomes were added in duplicate wells and changes in impedance across the hCMEC/D3 monolayer were continuously monitored in the electric cell-substrate impedance sensing instrument (Applied Biophysics Inc.) for up to 48 hours. Appropriate internalization of the exosomes by human brain microvascular endothelial cells was verified in a preliminary set of experiments using time-lapse confocal microscopy. Of note, the resistance across the hCMEC/D3 monolayer at confluence was measured at more than 800 Ω ⋅ cm2 (13). In addition, immunofluorescence staining of confluent hCMEC/D3 endothelial cell monolayers that were grown on 12-well cover slips for 24 hours in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum were also performed. Isolated exosomes from subjects were added individually to cover slips for 24 hours. Cells were fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 minutes at room temperature and then washed again with PBS. The cell membranes were permeabilized by incubation with 0.25% (vol/vol) Triton-X-100 in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the samples were blocked with 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin in PBS for 45 minutes at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with ZO-1 antibody (1:400; Life Technologies). Alexa 488 was used as secondary antibody (1:400; Life Technologies), and nuclear staining with DAPI (1:1000; Life Technologies) was performed. Appropriate controls and preadsorption experiments were performed to ascertain the specificity of the staining. Images were captured with a Leica SP5 Tandem Scanner Spectral 2-photon confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc.) with a 63× oil-immersion lens. For quantitative data comparisons, unpaired t tests were applied and a P value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

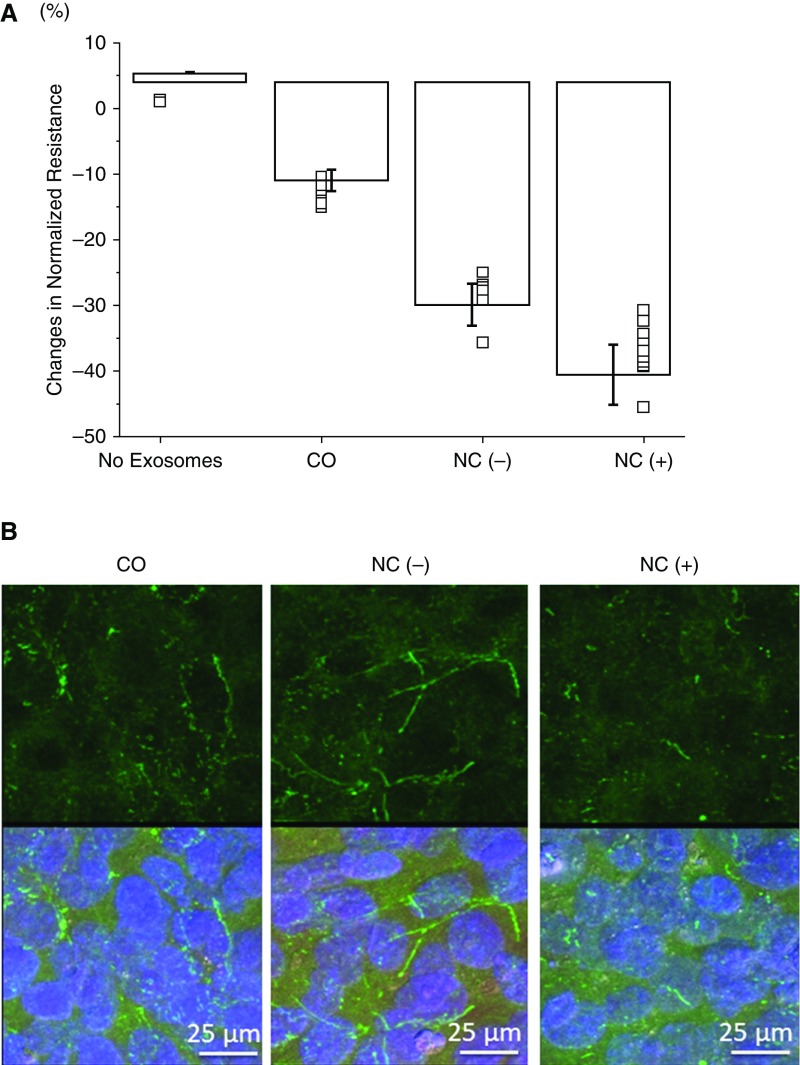

Plasma-derived exosomes from both OSA groups elicited significant declines in BBB transendothelial impedance compared with CO (Figure 1A; P < 0.001). Furthermore, the declines in impedance induced by NC+ exosomes were significantly larger than those of NC− (P < 0.01). In addition, ZO-1 immunostaining revealed significant and consistent disruption continuity of this tight junction protein in hCMEC/D3 cells treated with exosomes from NC+, but not when exosomes from the other 2 groups were added (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Changes in human brain microvascular endothelial cell model/D3 monolayer cell impedance after in vitro administration of plasma exosomes from children with obstructive sleep apnea with (NC+; n = 12), and without (NC−; n = 12) neurocognitive deficits and control subjects (CO; n = 6). Data are shown as mean ± SD. (B) Representative confocal microscope images (n = 6/group) of ZO-1 (zonula occludens-1) immunoreactivity (green) in human brain microvascular endothelial cell model/D3 cells treated with exosomes from CO, NC−, and NC+ subjects for 24 hours. Cells were also stained with DAPI (blue). The upper panel shows ZO-1 staining alone; the lower panel shows ZO-1 and DAPI staining together. The continuity of ZO-1 in NC− and CO is apparent but was always absent in NC+ cells.

Current findings show for the first time that circulating exosomes in children with OSA are capable of disrupting the integrity of the BBB, as illustrated by reduced impedance across the BBB, as well as increased discontinuity of ZO-1 along the cell membrane. Furthermore, the adverse effects of plasma exosomes on the BBB are accentuated in children with OSA who also manifest evidence of cognitive deficits. Although these studies are clearly descriptive in nature, and did not identify which elements of the exosome cargo underlie the functionally deleterious effects on the BBB, we postulate that differentially expressed cargo elements, such as microRNAs (2, 16), may play a mechanistic role in the emergence of such neurocognitive deficits by disrupting the BBB and by inducing the activation and propagation of pathophysiological cascades that ultimately foster astroglial and microglia inflammation and proliferation, increased reactive oxygen species formation, and ultimately increased neuronal cell losses, particularly in vulnerable brain regions (17).

Footnotes

The authors are supported by NIH grant HL130984 (L.K.-G.).

Author Contributions: A.K. performed experiments, analyzed data, and drafted components of the manuscript; D.G. participated in the conceptual framework of the project, provided critical input in all phases of the experiments, analyzed data, and edited versions of the manuscript; L.K.-G. provided the conceptual framework of the project, analyzed data, drafted components, and finalized the manuscript and is responsible for the financial support of the project and the manuscript content; and all authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201708-1636LE on October 20, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Hunter SJ, Gozal D, Smith DL, Philby MF, Kaylegian J, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Effect of sleep-disordered breathing severity on cognitive performance measures in a large community cohort of young school-aged children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:739–747. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2099OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khalyfa A, Kheirandish-Gozal L, Khalyfa AA, Philby MF, Alonso-Álvarez ML, Mohammadi M, et al. Circulating plasma extracellular microvesicle microrna cargo and endothelial dysfunction in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:1116–1126. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0323OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koren D, Dumin M, Gozal D. Role of sleep quality in the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:281–310. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S95120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea: oxidative stress, inflammation, and much more. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:369–375. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1190PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavie L. Oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea and intermittent hypoxia--revisited--the bad ugly and good: implications to the heart and brain. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;20:27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim DC, Pack AI. Obstructive sleep apnea and cognitive impairment: addressing the blood-brain barrier. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kheirandish-Gozal L, Khalyfa A, Gozal D. Exosomes, blood brain barrier, and cognitive dysfunction in pediatric sleep apnea. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2017;15:261–267. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim LJ, Martinez D, Fiori CZ, Baronio D, Kretzmann NA, Barros HM. Hypomyelination, memory impairment, and blood-brain barrier permeability in a model of sleep apnea. Brain Res. 2015;1597:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baronio D, Martinez D, Fiori CZ, Bambini-Junior V, Forgiarini LF, Pase da Rosa D, et al. Altered aquaporins in the brains of mice submitted to intermittent hypoxia model of sleep apnea. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;185:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilicarslan R, Alkan A, Sharifov R, Akkoyunlu ME, Aralasmak A, Kocer A, et al. The effect of obesity on brain diffusion alteration in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:768415. doi: 10.1155/2014/768415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guillemot L, Paschoud S, Pulimeno P, Foglia A, Citi S. The cytoplasmic plaque of tight junctions: a scaffolding and signalling center. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778(3):601–613. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood MJ, O’Loughlin AJ, Samira L. Exosomes and the blood-brain barrier: implications for neurological diseases. Ther Deliv. 2011;2:1095–1099. doi: 10.4155/tde.11.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolff A, Antfolk M, Brodin B, Tenje M. In vitro blood-brain barrier models: an overview of established models and new microfluidic approaches. J Pharm Sci. 2015;104:2727–2746. doi: 10.1002/jps.24329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gozal D, Crabtree VM, Sans Capdevila O, Witcher LA, Kheirandish-Gozal L. C-reactive protein, obstructive sleep apnea, and cognitive dysfunction in school-aged children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:188–193. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1519OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lötvall J, Hill AF, Hochberg F, Buzás EI, Di Vizio D, Gardiner C, et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: a position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3:26913. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.26913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalyfa A, Zhang C, Khalyfa AA, Foster GE, Beaudin AE, Andrade J, et al. Effect on intermittent hypoxia on plasma exosomal microRNA signature and endothelial function in healthy adults. Sleep. 2016;39:2077–2090. doi: 10.5665/sleep.6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philby MF, Macey PM, Ma RA, Kumar R, Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Reduced regional grey matter volumes in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44566. doi: 10.1038/srep44566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]