Abstract

Background

Despite recommendations from professional organizations supporting early hospice enrollment for patients with cancer, little research exists regarding end-of-life (EOL) practices for patients with malignant glioma (MG). We evaluated rates and correlates of hospice enrollment and hospice length of stay (LOS) among patients with MG.

Methods

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare-linked database, we identified adult patients who were diagnosed with MG from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2011 and who died before December 31, 2012. We extracted sociodemographic and clinical data and used univariate logistic regression analyses to compare characteristics of hospice recipients versus nonrecipients. We performed multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine predictors of hospice enrollment >3 or >7 days prior to death.

Results

We identified 12437 eligible patients (46% female), of whom 7849 (63%) were enrolled in hospice before death. On multivariable regression analysis, older age, female sex, higher level of education, white race, and lower median household income predicted hospice enrollment. Of those enrolled in hospice, 6996 (89%) were enrolled for >3 days, and 6047 (77%) were enrolled for >7 days. Older age, female sex, and urban residence were predictors of longer LOS (3- or 7-day minimum) on multivariable analysis. Median LOS on hospice for all enrolled patients was 21 days (interquartile range, 8–45 days).

Conclusions

We identified important disparities in hospice utilization among patients with MG, with differences by race, sex, age, level of education, and rural versus urban residence. Further investigation of these barriers to earlier and more widespread hospice utilization is needed.

Keywords: end-of-life care, health care disparities, hospice, malignant glioma, palliative care

Importance of the study

We present an analysis of end-of-life care for patients with malignant glioma as determined by analysis of SEER-Medicare data. Of the >12000 patients included in this study, we found that over 60% enrolled in hospice before death, and the vast majority of those met length-of-stay landmarks of 3 and 7 days, which are associated with higher quality end-of-life care. We explore predictors of hospice utilization and length of stay, including demographic and socioeconomic factors. This work not only highlights an understudied component of malignant glioma care, but also demonstrates potential disparities in care that warrant additional study.

Approximately 23000 Americans are diagnosed with primary malignant tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) each year; more than 90% of these tumors originate in the brain (primary malignant brain tumors).1 The majority (80%) of these tumors are World Health Organization (WHO) grades III–IV malignant glioma (MG), with a disease course characterized by high symptom burden, rapid progression, and low survival rates.2 Glioblastoma, the most common primary malignant brain tumor in adults, is an aggressive, relentlessly progressive, and uniformly fatal disease, with a median survival of approximately 15 months, and 5-year overall survival rate of only 5%.3 Despite the poor prognosis and rapid physical decline experienced by patients with MG, a critical knowledge gap exists regarding end-of-life (EOL) care among patients with MG.4 To date, the proportion of patients with MG who receive hospice services and their hospice length of stay (LOS) are unknown. Understanding the patterns and predictors of hospice use in this population may inform future efforts to improve the quality of EOL care for patients with MG. Further, the use of aggressive antineoplastic therapies in the terminal stages of cancer may lead to increased toxicities as well as costs, with minimal expected benefits to patients’ survival or quality of life.5 Thus, appropriate use of hospice and palliative care services has the potential to improve patient outcomes, prevent unwanted suffering, and reduce health care costs at EOL.

Hospice is a medical service focused on EOL care that benefits both patients and families.6–8 Family members of patients who receive hospice services report greater satisfaction with care, higher quality of death for the patient, and improved psychological outcomes compared with families of patients who do not receive hospice care.6 Unfortunately, patients often are admitted to hospice too late to derive many of these benefits.9 Estimates suggest that nearly 15% of patients with cancer enroll in hospice in the last 3 days of life.9,10 Overall, the median LOS for patients with cancer enrolled in hospice is only about 2 to 3 weeks.10–13 Thus, the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend hospice enrollment prior to death as a metric for high quality cancer care, and quality improvement initiatives have begun tracking 3- and 7-day hospice LOS.14 Despite these recommendations and the mounting evidence of the benefits of hospice for patients with cancer, little is known about hospice use among MG patients.

In this retrospective study, we sought to evaluate the rates and correlates of hospice use among patients with MG utilizing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare database. In addition to describing the proportion of MG patients enrolled in hospice and their LOS in hospice, we also aimed to identify predictive factors for overall hospice enrollment and hospice LOS. By describing the use of hospice services among patients with MG and identifying factors associated with hospice enrollment, findings from this work have the potential to inform future investigations seeking to enhance EOL care for patients with MG.

Methods

Data Source

The SEER database includes information about incident cancer cases from 17 affiliated cancer registries, covering approximately 26% of the US population. These data include information for patients between January 1, 1973 and December 31, 2012. The Medicare-linked database contains information from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for patients with cancer15 and includes information about the use of hospice services by patients enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare. The study was determined to be exempt by the Partners HealthCare institutional review board.

Study Sample

We used the SEER-Medicare database to retrospectively identify patients 18 years of age or older who were diagnosed with MG (histology of anaplastic astrocytoma, glioblastoma, or anaplastic oligodendroglioma) and subsequently passed away between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2012. We excluded the 13.7% of patients who did not have fee-for-service Medicare insurance, as well as those patients who were diagnosed with MG after entering hospice, or who were diagnosed with MG at autopsy.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We obtained data about patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics from the linked SEER-Medicare dataset. We collected baseline patient demographic information, including age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and urban versus rural residence. To estimate household income and level of education, we used patient zip codes to identify county of residence, and we linked this information to county-level median income and education data. As malignant gliomas do not have a recognized staging system, we did not collect additional extent of disease information. We also collected treatment characteristics, including extent of surgical resection (dichotomized into biopsy or subtotal resection versus gross total resection) and whether patients received radiation therapy.

Outcome Measures

To characterize differences in hospice use, we evaluated the following: enrollment in hospice prior to death (yes vs no), LOS in hospice (continuous variable, measured in days), LOS in hospice >3 days (yes vs no), and LOS in hospice >7 days (yes vs no). We defined enrollment in hospice prior to death as any patient who received inpatient, outpatient, or home-based hospice services, but excluding palliative care consultation as a sole indicator of hospice use, at any time between their date of MG diagnosis and date of death. We defined death while enrolled in hospice as any patient whose month and year of death matched the month and year of hospice termination. We calculated LOS in hospice by measuring days from hospice enrollment until death. We used hospice enrollment 3 days or less and 7 days or less prior to death as potential measures of suboptimal EOL care.14

Statistical Analysis

We performed all analyses using SAS version 9.4. We separated patients into 2 groups based on whether they enrolled in hospice prior to death. We used descriptive statistics to evaluate baseline features of each of these cohorts and univariate logistic regression analyses to compare socioeconomic, demographic, and treatment characteristics between hospice recipients and nonrecipients. We performed multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine predictors of hospice enrollment with regard to >3- or >7-day duration of hospice care prior to death. We included the following variables: age at diagnosis, sex (male or female), race (white, black, Hispanic, Asian, all others), marital status (married, unmarried, or unknown), extent of surgery (biopsy/subtotal resection, gross total resection, or unknown), treatment with radiation (received, not received, or unknown), median household income by zip code, residence in a rural zip code (yes or no), and level of education (percentage of adults age ≥25 y with a high school education, based on zip code and assessed at the county level). We chose these variables based on previously described predictors of hospice utilization in patients with cancer and prognostic factors for patients with MG.16–20 We used a Kaplan–Meier analysis to summarize duration of hospice enrollment for all patients.

Results

Table 1 displays patient characteristics. The total sample size of 12437 included 7849 patients (63.1%) enrolled in hospice prior to death and 4588 (36.9%) not enrolled in hospice prior to death. In both cohorts, the majority of patients were male, white, and married and lived in nonrural zip codes. Hospice recipients were older than nonhospice recipients, with mean age at diagnosis of 72.01 years (SD 9.84) in the hospice cohort compared with 67.90 years (SD 12.03) in the nonhospice group (P < 0.0001). Hospice recipients were also more likely than nonhospice recipients to be female, white, and unmarried. Seventy-seven percent of hospice claims filed were for inpatient services, while the remainder were either for home or non-acute inpatient care (eg, nursing facility).

Table 1.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of hospice recipients versus nonhospice recipients

| Characteristic | Hospice Recipients (n = 7849) | Nonhospice Recipients (n = 4588) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 72.01 (9.84) | 67.90 (12.03) | <0.0001 |

| Female (%) | 3820 (48.7) | 1879 (41.0) | <0.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| White | 6779 (86.4) | 3666 (79.9) | |

| Black | 342 (4.4) | 278 (6.1) | |

| Hispanic | 511 (6.5) | 398 (8.7) | |

| Asian | 200 (2.6) | 218 (4.8) | |

| All others* | 17 (0.2) | 28 (0.6) | |

| Marital Status (%) | 0.0072 | ||

| Married | 4732 (60.3) | 2873 (62.6) | |

| Unmarried | 2920 (37.2) | 1583 (34.5) | |

| Unknown | 197 (2.5) | 132 (2.9) | |

| Rural zip code (%) | 1088 (13.9) | 671 (14.6) | 0.2358 |

| Median household income by zip (SD) | 48 449.34 (11 132.61) | 48 583.52 (11 380.53) | 0.5198 |

| Surgery | 0.0003 | ||

| Biopsy/subtotal resection (%) | 5837 (74.4) | 3308 (72.1) | |

| Gross total resection (%) | 1854 (23.6) | 1213 (26.4) | |

| Unknown (%) | 158 (2.0) | 67 (1.5) | |

| Radiation Therapy | 0.0005 | ||

| Received (%) | 4791 (61) | 2962 (64.6) | |

| Not received (%) | 2836 (36.1) | 1507 (32.9) | |

| Unknown (%) | 222 (2.8) | 119 (2.6) |

*Including unknown race.

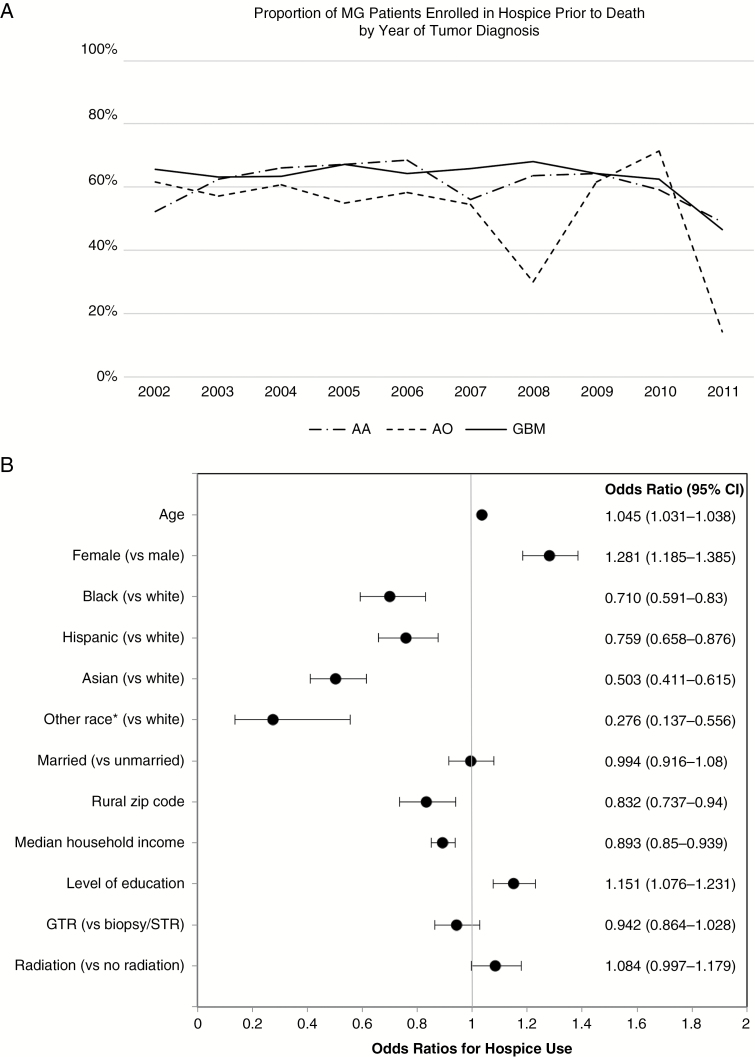

To evaluate patterns of hospice use over the decade studied, we explored the proportion of patients in our cohort who received hospice services prior to death within each of the disease groups (Fig. 1A). The proportion of patients receiving hospice was relatively stable per year for glioblastoma and anaplastic astrocytoma diagnoses, with the exception of the last 2 years of the studied period, which likely reflects that patients had not yet approached end of life by our study cutoff date of December 31, 2012. Notably, hospice use for anaplastic oligodendroglioma was generally lower than the other 2 included pathologies but was overall stable as well, aside from some moderate fluctuation and a similar decrease in usage near the study end. Overall, 92.7% of patients who enrolled in hospice died on hospice.

Fig. 1.

Hospice utilization and associated factors. (A) Proportion of malignant glioma patients enrolled in hospice prior to death by year of diagnosis. (B) Odds ratios and 95% CIs for potential predictors of hospice utilization in patients with malignant glioma. *Including unknown race.

To determine factors associated with hospice utilization, we performed multivariable logistic regression modeling (Fig. 1B). The odds of hospice enrollment prior to death were higher for patients who were older (odds ratio [OR] 1.045, 95% CI: 1.031–1.038), female (1.281, 1.185–1.385), and better educated (1.151, 1.076–1.231). Compared with white patients, the odds of hospice enrollment were significantly lower for black (OR 0.710, 95% CI: 0.591–0.83), Hispanic (0.759, 0.658–0.876), Asian (0.503, 0.411–0.615), and “all other” races, including unknown race (0.276, 0.137–0.556). The odds of hospice enrollment were lower with increasing household income (0.893, 0.85–0.939) and residing in a rural zip code (0.832, 0.737–0.94). Although marital status was associated with hospice utilization in univariate analysis, hospice enrollment in married patients was no longer significantly different from unmarried patients when controlling for all other covariates.

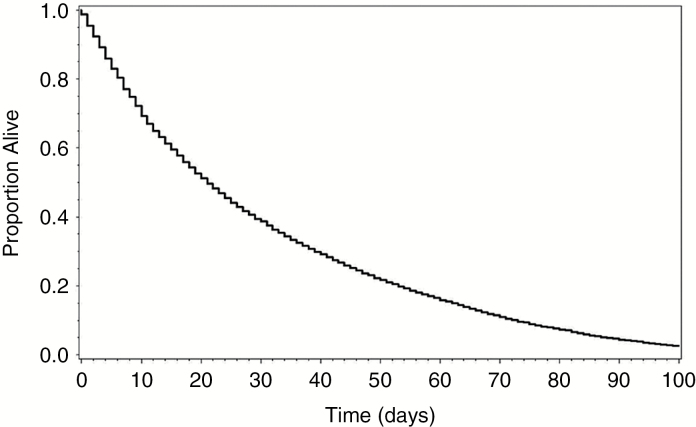

Hospice LOS for the entire cohort (n = 7849) was estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival from the time of hospice enrollment, with results shown in Fig. 2. Median LOS in hospice was 21 days, with interquartile range of 8–45 days.

Fig. 2.

Hospice length-of-stay. Kaplan–Meier curve demonstrating length of hospice services prior to death for patients with malignant gliomas.

We also used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate predictors of length of stay in hospice of greater than 3 and 7 days (Table 2). In the entire cohort of 7849 patients enrolled in hospice, 6996 patients (89.1%) were enrolled more than 3 days before death, and 6047 patients (77.0%) were enrolled in hospice more than 7 days before death. There were higher odds of a short stay in hospice, defined as enrollment in hospice within 3 days of death or within 7 days of death, in patients who were younger, male, and/or residing in a rural area. Although race, education, and household income were predictors of hospice enrollment, they were not associated with LOS in hospice greater than 3 and 7 days. There was no significant change in the proportion of patients with at least 3- or 7- day enrollment over the years studied.

Table 2.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with length of stay in hospice in patients with malignant glioma

| Timing of Hospice Enrollment | ||

|---|---|---|

| >3 Days Before Death, n = 6996 (89.1%) | >7 Days Before Death, n = 6047 (77.0%) | |

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.987 (0.979–0.995) | 0.990 (0.984–0.996) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Female | 1.332 (1.145–1.549) | 1.279 (1.144–1.429) |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Black | 1.112 (0.774–1.597) | 1.079 (0.826–1.408) |

| Hispanic | 1.349 (0.980–1.859) | 1.001 (0.807–1.242) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Unmarried | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Married | 1.007 (0.859–1.181) | 0.952 (0.846–1.071) |

| Rural zip code | 1.298 (1.023–1.647) | 1.245 (1.043–1.487) |

| Median household income | 1.094 (0.994–1.204) | 1.025 (0.956–1.100) |

| Level of education | 1.069 (0.942–1.214) | 1.094 (0.995–1.203) |

| Surgery | ||

| Biopsy/subtotal resection | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Gross total resection | 1.076 (0.903–1.282) | 1.084 (0.953–1.234) |

| Radiation Therapy | ||

| Not received | 1.000 | 1.00 |

| Received | 1.006 (0.859–1.179) | 1.000 (0.889–1.124) |

Discussion

In this large, retrospective study utilizing SEER-Medicare data, we found that over 60% of patients with MG enrolled in hospice prior to death, a proportion that was relatively stable over time. Importantly, we also identified certain patient characteristics, such as age and sex, that are associated with whether patients receive hospice services prior to death. In addition, for those patients who received hospice services, we found that most were enrolled in hospice greater than 7 days prior to death, yet nearly 25% only received hospice care for under a week. Notably, we identified similar characteristics, such as age and sex, that were associated with whether patients received hospice services greater than 3 or 7 days prior to death. Thus, our findings provide valuable new insights about the rates and correlates of hospice use among patients with MG.

Despite recommendations from professional organizations to track hospice use among patients with cancer,14 little research exists with regard to current EOL practices for patients with MG. Previous studies have demonstrated rates and correlates of hospice use among a broad range of non-CNS cancer types.21–27 Although one prior study investigated late referrals to home hospice in patients with primary malignant brain tumors,16 no studies to date have described overall patterns and predictors of hospice referral in this population. As MGs are extremely aggressive cancers with a dismal prognosis, EOL care is of utmost importance for patients. Notably, we found that over 60% of patients with MG received hospice prior to death, which was relatively stable over the decade studied. Although treatments evolved over this interval, this highlights the ingrained practice pattern of hospice referral before end of life for a majority of MG patients regardless of therapies received. This hospice enrollment rate is similar to those seen in other cancer populations.8,28 Similarly, this matches the self-reported rate of hospice use among neuro-oncology providers surveyed regarding palliative care practices; the majority of neuro-oncology clinicians in the US and Canada (63%) reported referring more than 50% of their patients to hospice for EOL care; 44% of respondents reported referring >75% of their patients with MG to hospice.29

Importantly, we found that median LOS in hospice in our study was 3 weeks. However, nearly a quarter of MG hospice recipients enrolled in hospice in the last week of life, and 11% spent 3 or fewer days in hospice prior to death. These are lower than the percentage of short hospice stays previously noted in the oncology literature, where reports suggest that 14.3% of patients with cancer enroll in hospice within 3 days of death, with significant variability by cancer type in the percentage of hospice enrollees with short stays.9,12,13 Concordant with this finding, previous studies also have demonstrated a pattern of earlier hospice referral for patients with CNS tumors and longer stays in hospice compared with other solid tumors.12,13 The reasons for longer hospice LOS for patients with MG are largely unknown, but may be related to the aggressive nature of these tumors, which may prompt earlier EOL care discussions between patients and clinicians. Alternatively, prognosis may be more reliably predicted for patients with MG than other cancer types, thereby resulting in earlier EOL discussions and hospice referrals. Moreover, perhaps cultural/training differences exist between neuro-oncologists and other solid tumor oncologists, and this warrants further investigation. Thus, although we found high rates of hospice enrollment among patients with MG, additional research is needed to better understand the reasons for these higher rates of hospice enrollment while also continuing to develop strategies to improve EOL care for patients with MG.

We found lower odds of hospice enrollment for younger, male, less educated, nonwhite, and rural-dwelling patients. Prior studies of disparities in hospice utilization have demonstrated that substantial barriers to hospice access exist for racial and ethnic minorities. Although the cause of this disparity is not entirely understood, studies suggest that cultural differences and socioeconomic factors may play a role.30–33 Rural residence, male sex, and younger age have an established association with decreased hospice utilization in other cancer populations.21,34,35 We also found higher risk of shorter hospice LOS in male, younger, and rurally based patients. Previous studies have shown that hospice LOS for minorities is generally equal to or longer than that for whites18,31; similarly, we found no association between race and duration of hospice use.

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis of factors associated with hospice services is limited to factors available in the SEER–Medicare-linked database. Thus, we lack information about patient preferences, functional impairments, physician characteristics, and other factors that may potentially influence hospice use. Second, our study population is restricted to patients with fee-for-service Medicare living within areas included in the SEER program of population-based cancer registries. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to patients outside of this population. In addition, the SEER-Medicare database only allows for assessment of socioeconomic variables such as level of education and income based on zip code of residence and assessed at the county level. In contrast to the bevy of literature demonstrating reduced access to and/or utilization of palliative care services and hospice for low-income patients,17,36–38 we found that the odds of hospice enrollment were lower with increasing household income. While it is possible that this is a true association due to unclear factors in this patient population, we suspect that this is an artifact of the SEER-Medicare data’s reliance upon county-level income data rather than individual income data.

Our study highlights important disparities in hospice utilization among patients with MG. We found differences by race, sex, age, level of education, and rural versus urban residence. We also describe important predictors of a suboptimal short stay in hospice (≤3 days or ≤7 days), including younger age, male sex, and rural place of residence. We hope our findings will motivate additional research investigating ways to enhance EOL care for patients with MG. A better understanding of the barriers to earlier and more widespread hospice utilization for MG patients will facilitate the development of tailored interventions aimed at improving EOL care for this population with unique EOL care needs.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Cancer Institute Paul Calabresi Career Development Award for Clinical Oncology (K12)/K12CA090354-13 (to J.T.J.).

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Liao P et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2007–2011. Neuro Oncol. 2014; 16(Suppl 4):iv1–iv63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walbert T. Integration of palliative care into the neuro-oncology practice: patterns in the United States. Neurooncol Pract. 2014;1(1):3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Catt S, Chalmers A, Fallowfield L. Psychosocial and supportive-care needs in high-grade glioma. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(9):884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. The health impact of health care on families: a matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(3):465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Godkin MA, Krant MJ, Doster NJ. The impact of hospice care on families. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1983;13(2):153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1888–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue?J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3860–3866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miesfeldt S, Murray K, Lucas L, Chang CH, Goodman D, Morden NE. Association of age, gender, and race with intensity of end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):548–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO’s Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America September 2015; https://http://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2015_Facts_Figures.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2017.

- 12. Wang X, Knight LS, Evans A, Wang J, Smith TJ. Variations among physicians in hospice referrals of patients with advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(5):e496–e504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, Ache K, Casarett DJ. Hospice admissions for cancer in the final days of life: independent predictors and implications for quality measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(28):3184–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campion FX, Larson LR, Kadlubek PJ, Earle CC, Neuss MN. Advancing performance measurement in oncology: quality oncology practice initiative participation and quality outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3 Suppl):31s–35s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, Mentnech RM, Kessler LG. Potential for cancer related health services research using a linked Medicare-tumor registry database. Med Care. 1993;31(8):732–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diamond EL, Russell D, Kryza-Lacombe M et al. Rates and risks for late referral to hospice in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(1):78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fairfield KM, Murray KM, Wierman HR et al. Disparities in hospice care among older women dying with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(1):14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Park NS, Carrion IV, Lee BS, Dobbs D, Shin HJ, Becker MA. The role of race and ethnicity in predicting length of hospice care among older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(2):149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alvarez de Eulate-Beramendi S, Alvarez-Vega MA, Balbin M, Sanchez-Pitiot A, Vallina-Alvarez A, Martino-Gonzalez J. Prognostic factors and survival study in high-grade glioma in the elderly. Br J Neurosurg. 2016; 30(3):330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lacroix M, Abi-Said D, Fourney DR et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J Neurosurg. 2001;95(2):190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Barriers to hospice care among older patients dying with lung and colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown AJ, Sun CC, Prescott LS, Taylor JS, Ramondetta LM, Bodurka DC. Missed opportunities: patterns of medical care and hospice utilization among ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(2):244–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sammon JD, McKay RR, Kim SP et al. Burden of hospital admissions and utilization of hospice care in metastatic prostate cancer patients. Urology. 2015;85(2):343–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sanoff HK, Chang Y, Reimers M, Lund JL. Hospice utilization and its effect on acute care needs at the end of life in medicare beneficiaries with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(3):e197–e206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shin JA, Parkes A, El-Jawahri A et al. Retrospective evaluation of palliative care and hospice utilization in hospitalized patients with metastatic breast cancer. Palliat Med. 2016;30(9):854–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Odejide OO, Cronin AM, Earle CC, LaCasce AS, Abel GA. Hospice use among patients with lymphoma: impact of disease aggressiveness and curability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016; 108(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, Riley AW, King L, Smith TJ. Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):195–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Temel JS, McCannon J, Greer JA et al. Aggressiveness of care in a prospective cohort of patients with advanced NSCLC. Cancer. 2008;113(4):826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walbert T, Puduvalli V, Taphoorn MJB, Taylor A, Jalali R. International patterns of palliative care in neuro-oncology: a survey of physician members of the Asian Society for Neuro-Oncology, the European Association of Neuro-Oncology, and the Society for Neuro-Oncology. Neuro-Oncology Practice. 2015; 0:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Greiner KA, Perera S, Ahluwalia JS. Hospice usage by minorities in the last year of life: results from the National Mortality Followback Survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(7):970–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fishman J, O’Dwyer P, Lu HL et al. Race, treatment preferences, and hospice enrollment: eligibility criteria may exclude patients with the greatest needs for care. Cancer. 2009;115(3):689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ngo-Metzger Q, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. Ethnic disparities in hospice use among Asian-American and Pacific Islander patients dying with cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):139–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang H, Qiu F, Boilesen E et al. Rural-urban differences in costs of end-of-life care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Rural Health. 2016;32(4):353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sharma N, Sharma AM, Wojtowycz MA, Wang D, Gajra A. Utilization of palliative care and acute care services in older adults with advanced cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O’Mahony S, McHenry J, Snow D, Cassin C, Schumacher D, Selwyn PA. A review of barriers to utilization of the Medicare hospice benefits in urban populations and strategies for enhanced access. J Urban Health. 2008;85(2):281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lyckholm LJ, Coyne PJ, Kreutzer KO, Ramakrishnan V, Smith TJ. Barriers to effective palliative care for low-income patients in late stages of cancer: report of a study and strategies for defining and conquering the barriers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2010;45(3):399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Riggs A, Breuer B, Dhingra L et al. Hospice enrollment after referral to community-based, specialist-level palliative care: incidence, timing, and predictors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(2):170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]