Abstract

Background

Glioblastoma (GBM) is difficult to treat. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) is an attractive therapeutic target for GBM; however, targeting this pathway to effectively treat GBM is not successful because the roles of PI3K isoforms remain to be defined. The aim of this study is to determine whether PIK3CB/p110β, but not other PI3K isoforms, is a biomarker for GBM recurrence and important for cell survival.

Methods

Gene expression and clinical relevance of PI3K genes in GBM patients were analyzed using online databases. Expression/activity of PI3K isoforms was determined using immunoblotting. PI3K genes were inhibited using short hairpin RNAs or isoform-selective inhibitors. Cell viability/growth was assessed by the MTS assay and trypan blue exclusion assay. Apoptosis was monitored using the caspase activity assay. Mouse GBM xenograft models were used to gauge drug efficacy.

Results

PIK3CB/p110β was the only PI3K catalytic isoform that significantly correlated with high incidence rate, risk, and poor survival of recurrent GBM. PIK3CA/p110α, PIK3CB/p110β, and PIK3CD/p110δ were differentially expressed in GBM cell lines and primary tumor cells derived from patient specimens, whereas PIK3CG/p110γ was barely detected. PIK3CB/p110β protein levels presented a stronger association with the activities of PI3K signaling than other PI3K isoforms. Blocking p110β deactivated PI3K signaling, whereas inhibition of other PI3K isoforms had no effect. Specific inhibitors of PIK3CB/p110β, but not other PI3K isoforms, remarkably suppressed viability and growth of GBM cells and xenograft tumors in mice, with minimal cytotoxic effects on astrocytes.

Conclusions

PIK3CB/p110β is a biomarker for GBM recurrence and selectively important for GBM cell survival.

Keywords: glioblastoma, PI3K isoform, PIK3CB/p110β, PI3K-isoform selective inhibitors, tumor recurrence

Importance of the study

GBM is a lethal disease and there is no known cure. Genes in the PI3K signaling pathway are frequently mutated in this cancer. PI3K inhibitors have therefore been used to treat GBMs with modest benefits in the clinic, mainly because these drugs are nonselective and highly toxic. In this work, we find that PIK3CB/p110β is more important for GBM cell survival and causes less toxicity to normal astrocytes, compared with other PI3K isoforms. These results highlight the importance of selectively targeting PIK3CB/p110β to treat GBM patients with elevated levels of this isoform. Our work will impact the GBM research field by providing new evidence for the divergent roles of PI3K isoforms in GBM recurrence and cell survival, revealing new mechanistic insights of GBM disease progression, and fostering rational design of new GBM therapies.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common brain malignancy, accounting for greater than 46% of all malignant brain tumors.1 Patients with GBM have a median survival time of 14.6 months following maximum surgical resection, ionizing radiation, and chemotherapy.2 GBM ranks as the most lethal form of all brain cancers because the 5-year overall survival for GBM patients is approximately 5%.1 After aggressive treatment, more than 90% of patients have a recurrent tumor within 2 years and live on average for 5 to 7 months.3 Recurrent GBM tends to be highly resistant to chemotherapy and radiation, and consequently no standard-of-care treatment currently exists. Hence, it is imperative to find new and effective treatments for GBM.

To identify novel therapeutic targets, we carried out an RNA interference screen in a previous study and identified 20 human kinase genes as important survival factors for U87MG GBM cells.4 Further examination using the clinical data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) led to the identification of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for GBM recurrence. One candidate biomarker is phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit β (PIK3CB), which encodes a catalytic subunit p110β of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) gene family. This family consists of kinases that transmit extracellular signals from growth factors, cytokines, and other environmental inputs into intracellular signals that regulate a multitude of signaling pathways.5

In mammals, there are 4 classes of PI3K (classes IA, IB, II, and III). Class IA PI3K consists of 3 homologous isoforms—PIK3CA, PIK3CB, and PIK3CD—that encode catalytic subunits p110α, p110β, and p110δ, respectively. These subunits bind to one p85 regulatory subunit (α, β, or γ) encoded by PIK3R1, PIK3R2, and PIK3R3 to form a heterodimer. Class IB PI3K has the fourth catalytic isoform, PIK3CG (encoding p110γ), which interacts with its regulator p101 encoded by PIK3R5. This p110γ subunit is nearly exclusively expressed in immune cells.6 Class IA PI3Ks bind to and convert membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), which is a secondary messenger that activates V-Akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT)/glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) to sustain cell survival.5

Research in exploring the role of PI3K isoforms in GBM is still in its infancy. However, results from prior studies are often contradictory and inconsistent. For instance, depletion of PIK3CB, but not of PIK3CA, inhibited the growth of U87MG cells7 and sensitized these cells to apoptosis induced by an apoptosis-inducing ligand.8 In U251 cells, PIK3CB/p110β knockdown impeded their growth in culture and in mice as a single agent,9 or together with ectopically expressed phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN).10 In contrast, PIK3CA/p110α inhibition failed to block AKT activation in U251 and U87MG cells and to synergize with PTEN to inhibit tumor cell growth.7,10 These results suggest that p110β is more important than p110α in controlling GBM cell survival. However, Hu et al found that depleting PIK3CA also reduced the levels of phosphorylated (p)AKT in U87MG cells.11 Höland et al showed that PIK-75 (a p110α-selective inhibitor), but not TGX-221 (a p110β-selective inhibitor), inhibited the growth of T98G cells, despite both inhibitors effectively blocking AKT activation.12 In all studies described above, expression of PI3K isoforms was not examined in GBM cell lines harboring different genetic mutations in PI3K signaling (eg, PTEN). In addition, most of these studies lack further corroborating evidence in clinical tumor samples. Hence, the roles of PI3K isoforms in GBM still remain to be fully defined.

Here, we report that, based on clinical data from TCGA database, PIK3CB was an important biomarker among all PI3K isoforms for predicting the incidence rate, risk, and prognosis of GBM recurrence. Further analyses in 9 GBM cell lines, 8 primary tumor cells, 6 primary glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs), and U87MG/SF-295 xenograft mouse models have established PIK3CB as a unique and critical survival factor for GBM, highlighting the importance of selectively targeting PI3K genes to treat GBM.

Materials and Methods

Cells

GBM cell lines, primary GBM cells, and human astrocytes (kindly provided by Dr Scott Verbridge at Virginia Tech) were maintained and GSC lines were prepared as described previously.13

Chemicals

Compounds listed in this study were purchased from AdooQ Bioscience. All chemicals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at stock concentrations ranging from 10 to 50 mM.

Analysis of PI3K Gene Expression Using Online Databases

Gene expression analysis was described previously with modifications.4 The expression data of PI3K genes were retrieved from BioGPS, the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE), TCGA, and the Human Protein Atlas. For the data from BioGPS and CCLE, the arbitrary copy numbers of each individual PI3K mRNA in 16 tumor cell lines or 2 normal cell lines were averaged and shown. The GlioVis program collects data from the database of TCGA. The PI3K gene expression data from TCGA were retrieved using the GlioVis program. Messenger RNA levels (log2) of PI3K genes were replotted. Immunohistochemical staining images of tumor or normal tissues were retrieved from the Human Protein Atlas. The inset figures describing the staining details were cropped using Photoshop. Samples with different scales of protein staining in tumor or normal tissues were counted.

Clinical Analyses Using TCGA GBM Patient Data

GBM patient survival analyses were performed as previously described.4 In brief, clinical variables of GBM patients were retrieved from the Data Portal of TCGA (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). Gene expression data for GBM patients (AgilentG4502A071; AgilentG4502A072) were downloaded from the Pan-cancer project (syn1461183) on Synapse (http://www.synapse.org). Recurrent GBM patients were divided into high level (top 25%) and low level (bottom 25%) based on the mRNA levels of PI3K genes. Recurrent tumor rates were predicted using contingency analysis, and Fisher’s exact test was performed using JMP software (SAS Institute). The recurrence risk was determined by days to recurrence in recurrent GBM patients. A Cox proportional hazards model was performed using JMP software.

Isolation and Preparation of Primary GBM Cells and GSCs

The institutional review board at Carilion Clinic has approved the collection and use of human GBM specimens from de-identified patients in our studies. Primary GBM cells and GSCs were isolated as described previously.13 Briefly, GBM tumors were minced into small pieces. Single cells were prepared using Liberase (Roche Diagnostics). Red blood cells were removed using the red blood cell lysis solution (Miltenyi Biotec). To isolate GSCs, single tumor cells were incubated in stem cell culture media for several weeks to months. Isolated GSCs grew as spheres. When spheres were visible by naked eye, they were dissociated to single cells using TrypLE (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Healthy spheres were frozen in stem cell media with 7% DMSO.

Gene Knockdown by Short Hairpin RNAs

Short hairpin (sh)RNAs of PI3K genes were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (PIK3CA-1: RHS4884-101656238; PIK3CA-2: RHS4884-101656239; PIK3CB-1: RHS4884-101656350; PIK3CB-2: RHS4884-101656783; PIK3CA/B: RHS4884-101656236; PIK3CD-1: RHS4884-101656777; and PIK3CD-2: RHS4884-101656787). Lentiviruses of individual shRNAs were made according to the manufacturer’s instruction—5 × 105 GBM cells were seeded and transduced with lentiviruses of nonsilencing shRNA or shRNAs of PI3K isoforms. Cells were then selected with 0.25 to 0.5 μg/mL puromycin for 4 to 7 days. In some cases, cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding shRNAs. Knockdown efficiency was assessed using immunoblotting.

Immunoblotting and Quantitative Analysis of Protein Intensities

Immunoblotting was performed as described in our previous reports.4,14–16 All the antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, except anti–β-actin (ACTB) antibody, which was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The intensities of protein bands were quantified using ImageJ software. The relative intensities were obtained by dividing the intensity of each protein by those of ACTB (loading control) and total AKT, in the case of phosphorylated AKT (pAKT). For some experiments, the fold changes of proteins were obtained by dividing the intensities of experiments by those of the control.

Cell Proliferation Assays

We used the MTS viability assay14,16 and the trypan blue exclusion assay to determine cell growth. In brief, cells were plated in a 96-well plate or a 12-well plate. Cells were then treated with DMSO and chemical inhibitors at the indicated doses. After 4 days, cell viability or cell number was measured using MTS or determined using trypan blue staining followed by cell counting. Percent cell viability or growth was obtained by dividing the absorbance or live cell number of treatment groups by those of untreated groups. Values of half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) were calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

Mouse Experiments

Mouse experiments were performed based on methods described previously, with modifications.14,16 All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Tech. U87MG or SF-295 cells (2 × 106) were mixed with Matrigel Matrix (Corning) and subcutaneously injected into severe combined immunodeficient/beige mice. Six to 12 days after cell injection, mice were randomly divided into 3 groups to receive the following treatments: (i) DMSO, (ii) 40 mg/kg TGX-221, and (iii) 30 mg/kg GSK2636771. Drugs were administered daily through intraperitoneal injection for 2 weeks. During the treatment, tumors were measured daily using a caliper. On day 21 or 41, mice were euthanized and tumors were harvested. Tumor volumes (mm3) were calculated using the formula: (length × width2)/2.

Statistical Analyses

Student’s t-test was used to determine the difference of means between the control and treatment groups in gene expression analysis and mouse experiments.

Results and Discussion

Expression of class I PI3K Genes in GBM

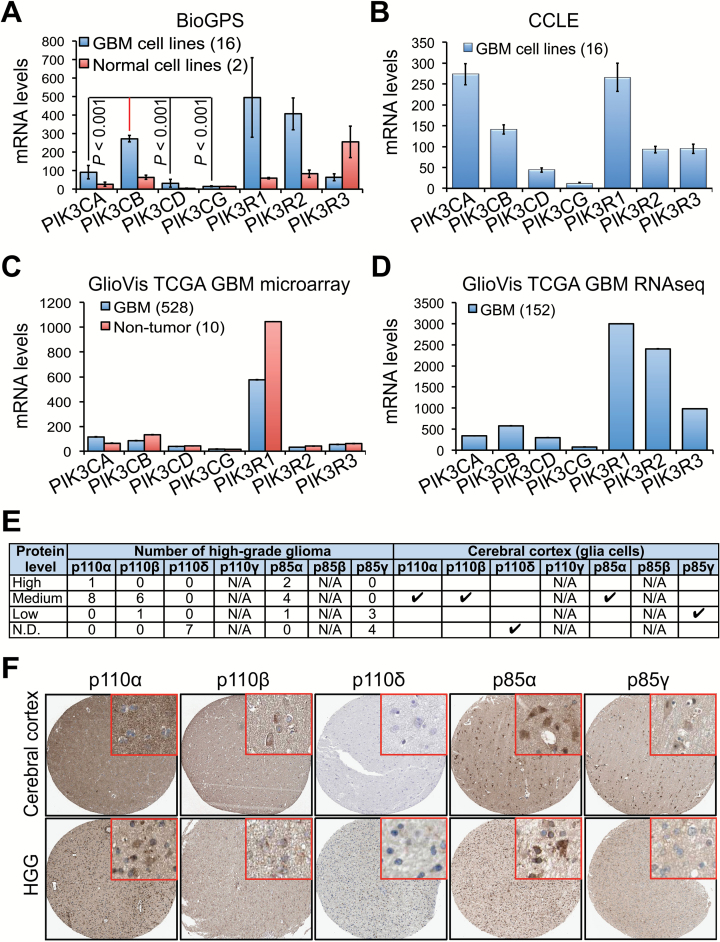

We first compared the expression levels of PI3K genes using the online programs BioGPS (Fig. 1A) and CCLE Fig. 1B). Messenger RNA levels of PIK3CB and PIK3CA were significantly higher than those of PIK3CD and PIK3CG in GBM cell lines. PIK3CG mRNA was barely detected. The mRNA levels of PI3K regulatory subunits (PIK3R1, PIK3R2, and PIK3R3) were also different. We next analyzed microarray (Fig. 1C) or RNA sequencing (Fig. 1D) data collected from hundreds of patient tissue specimens (TCGA) using the GlioVis program. Similarly, PIK3CB and PIK3CA were highly expressed, with low levels of PIK3CG in tumor tissues. While we observed a significantly lower expression of PI3K genes in 2 normal cell lines (astrocytes and human embryonic kidney 293 cells), except PIK3R3 (Fig. 1A), there was no significant difference in PI3K gene expression between GBM and non-tumor tissues (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

PIK3CB/p110β is highly expressed in GBM. (A) Messenger RNA levels of 4 PI3K catalytic and 3 regulatory subunits in 16 different GBM cell lines and 2 normal cell lines (human embryonic kidney 293 and astrocytes). Complementary DNA microarray data were retrieved from the BioGPS database. P-values denote the difference between the levels of PIK3CB and those of other PI3K genes in GBM cell lines. (B) Messenger RNA levels of PI3K genes in 16 GBM cell lines; different from those in (A). Microarray data were retrieved from CCLE. (C) Messenger RNA levels of PI3K genes in 528 primary GBM specimens and 10 non-tumor tissues. Complementary DNA microarray data were retrieved from the database of TCGA and analyzed using the GlioVis program. (D) Messenger RNA levels of PI3K genes in 152 primary GBM specimens. RNA sequencing data were retrieved from the database of TCGA and analyzed using the GlioVis program. (E) Summary of PI3K protein levels determined by immunohistochemical staining. Data were retrieved from the Human Protein Atlas database. Case numbers of high-grade gliomas (HGGs) are shown. N/A: not available. Results in normal brain are based on immunohistochemical staining of a single sample. (F) Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for p110α, p110β, p110δ, p85α, and p85γ in cerebral cortex and HGG specimens. Inset figures show the details of protein staining.

We also examined the expression of class IA PI3K proteins in normal and malignant tissues by querying data from the Human Protein Atlas. PIK3CA/p110α and PIK3CB/p110β were expressed at medium levels, whereas PIK3CD/p110δ was not detected (Fig. 1E, F). PIK3R1/p85α levels were medium or high in comparison with low or undetectable levels of PIK3R3/p85γ. Additionally, no significant difference of PI3K protein levels was detected between normal and malignant tissues (Fig. 1E). Taken together, our results demonstrate that the mRNA and protein levels of PIK3CA/p110α and PIK3CB/p110β are relatively higher than those of PIK3CD/p110δ or PIK3CG/p110γ in GBM tumor cells and tissues.

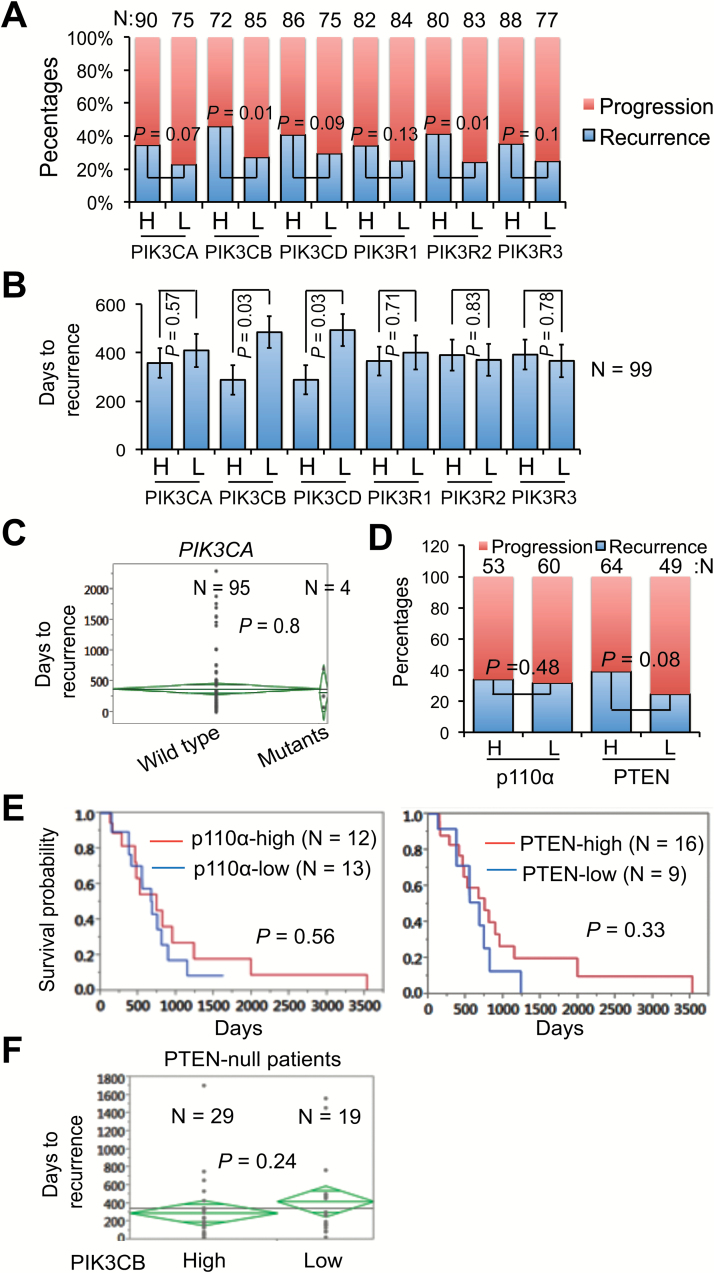

Clinical Relevance of class IA PI3K Genes with GBM Recurrence

Next, we sought to determine the clinical relevance of class IA PI3K genes with tumor recurrence. The PIK3CG isoform was minimally detected in GBM (Fig. 1), and therefore was excluded in further analyses. Based on the expression and clinical data from more than 500 GBM patients in the database of TCGA, we divided the patients who had progressive disease (eg, tumor recurrence, drug resistance, tumor-related neurological disorders, death) into high (H) and low (L) expression groups of class IA PI3K genes. As shown in Fig. 2A, the percentage of tumor recurrence (blue bars) was consistently higher in H groups than in L groups. Among all class IA PI3K genes, only PIK3CB and PIK3R2 displayed a statistically significant difference between H and L groups (P = 0.01, respectively), suggesting that patients have greater chances of tumor recurrence if PIK3CB or PIK3R2 levels are high. To determine recurrence risk, we measured days to tumor recurrence in 99 recurrent GBM patients. We found that H group patients developed another tumor much faster than L group patients in class IA PI3K genes except for PIK3R2 and PIK3R3 (Fig. 2B). However, statistical analyses only detected a significant difference between H and L groups of PIK3CB or PIK3CD (P = 0.03, respectively). Furthermore, we determined the correlation of class IA PI3K genes and recurrence-associated patient survival using Cox univariate analysis or multivariate analysis crossed with temozolomide (TMZ), a frontline chemotherapy agent for GBM.17 The hazard ratio (chance of death) for patients with high levels of PIK3CB or PIK3CD was 3.61 or 4.23, respectively (P < 0.05; Table 1). In contrast, the hazard ratios of other genes were low (from 0.46 to 1.52) with no statistical significance (P > 0.05). No significant changes in hazard ratios were found in PI3K genes when TMZ was used as a covariate, consistent with the fact that recurrent GBMs are resistant to chemotherapy.3 In all clinical analyses presented above, only PIK3CB showed a strong and statistically significant correlation with the incidence rate, risk, and patient survival of GBM recurrence.

Fig. 2.

Levels of PIK3CB/p110β correlate with the incidence rate, risk, and survival of recurrent GBMs. (A) Correlation of PI3K mRNAs and GBM recurrence rate. GBM patients from the database of TCGA were divided into 2 groups with either high (H) or low (L) levels of PI3K mRNAs. Percentages of patients with recurrence-free progression (Progression) or recurrent tumors (Recurrence) are shown. Recurrence rate is defined as the percentage of patients with recurrent tumors over patients with a progressed disease. P-values denote the difference of patients with recurrent tumors that express high or low levels of PI3K mRNAs. Sample sizes (N) in each group are shown. (B) Correlation of PI3K mRNAs and recurrence risk. Recurrence risk is defined as days to recurrence after surgery. Ninety-nine GBM patients with recurrent tumors were analyzed. (C) PIK3CA mutations and recurrence risk. (D) Correlations between protein levels of p110α or PTEN and recurrence rates. (E) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of p110α or PTEN protein levels in recurrent GBMs. Data were retrieved from the database of TCGA. Recurrent GBMs were divided into high or low groups depending on the levels of p110α or PTEN proteins. (F) Correlation of PIK3CB mRNA levels with recurrence risk in PTEN-null patients. Data were retrieved from the database of TCGA.

Table 1.

Correlation of PI3K gene expression and the survival of recurrent GBMs

| Gene Symbol | Recurrence-Associated Survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox Univariate | Cox Multivariate with TMZ | |||

| Hazard Ratio | P-value | Hazard Ratio | P-value | |

| PIK3CA | 1.42 | 0.10 | 1.42 | 0.10 |

| PIK3CB | 3.61 | 0.02 | 3.63 | 0.02 |

| PIK3CD | 4.23 | 0.01 | 4.35 | 0.01 |

| PIK3CG | 1.52 | 0.48 | 1.52 | 0.48 |

| PIK3R1 | 1.31 | 0.60 | 1.33 | 0.58 |

| PIK3R2 | 0.46 | 0.25 | 0.45 | 0.24 |

| PIK3R3 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

Note: Hazard ratios denote the chance of death. P-values determine the statistical significance of hazard ratios.

Genetic mutations in PTEN and PIK3CA have been reported previously.18 We then retrieved genome-sequencing data of 99 recurrent GBM patients from TCGA. We found that 4 patients carried mutations in PIK3CA. However, progression to recurrence in patients with wild type PIK3CA was similar to that in patients with mutant PIK3CA (P = 0.8; Fig. 2C). We also analyzed the reverse phase protein array data from the database of TCGA. Protein levels of PIK3CA/p110α and PTEN failed to correlate with the incidence rate of tumor recurrence (Fig. 2D) or the survival of recurrent GBM patients (Fig. 2E). We next tested whether PIK3CB cooperates with PTEN deficiency in GBM recurrence. We found no difference of recurrence risk in PTEN-null patients with high or low levels of PIK3CB (Fig. 2F), suggesting that PIK3CB is independent of PTEN deficiency in tumor recurrence. Taken together, our results demonstrate that PIK3CB is an important biomarker for GBM recurrence, compared with other PI3K isoforms and PTEN.

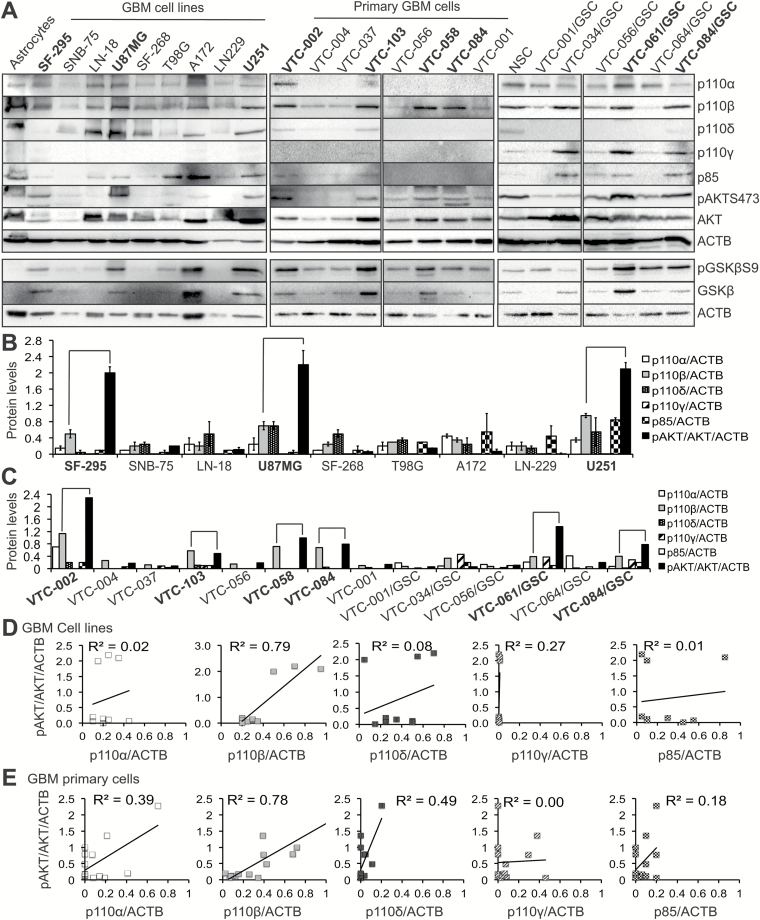

PI3K Catalytic Isoforms and AKT Activation in GBM

To help clarify the roles of PI3K catalytic isoforms in AKT activation, we determined their expression in 9 GBM cell lines with different genetic backgrounds (PTEN deficiency, Supplementary Figure S1), 8 lines of primary GBM cells, and 6 lines of GSCs.13 Based on the results from 2 sets of immunoblotting (left panel, Fig. 3A and Supplementary Figure S1), we found that p110α, p110β, and p110δ were expressed in astrocytes and all GBM cell lines at different levels, while p110γ was undetectable. Consistent results were found in primary GBM cells and GSCs (middle and right panels, Fig. 3A), except that p110α and p110δ levels were low in primary cells and p110δ was merely detected in GSCs. Intriguingly and unexpectedly, p110γ was expressed at a relatively high level in several lines of GSCs (right panel, Fig. 3A). This might be caused by different culture conditions for primary GBM cells or GSCs. We also measured the levels of p85 using an antibody that recognizes all p85 isoforms. We found that p85 was expressed in GBM at relatively low levels (Fig. 3A). Quantification of protein band intensities verified the differential expression of PI3K isoforms in GBM cells (Fig. 3B–C).

Fig. 3.

Levels of p110β protein strongly correlate with AKT activation. (A) Immunoblotting of 4 PI3K catalytic subunits, p85, pAKTS473 (phosphorylated AKT at serine 473), AKT, pGSK3βS9 (phosphorylated GSK3β at serine 9), GSK3β, and actin (ACTB) in human astrocytes, 9 GBM cell lines, 8 primary GBM cells, neural stem cells, and 6 GSC lines. Four catalytic subunits are shown. Primary cells and GSCs were derived from freshly dissected tumor tissues. ACTB is the loading control. Quantitative analyses of protein band intensities in cell lines (B) or primary cells (C) using ImageJ software. Intensity of each protein was normalized to those of ACTB to obtain relative intensities. To determine the extent of AKT activation, intensities of pAKT were divided by those of AKT and further normalized by the fold changes of ACTB in GBM cell lines compared with astrocytes. Error bars were obtained from 2 independent sets of experiments. The other set of immunoblots is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Cells with corresponding high levels of p110β and pAKT (connected by lines) are highlighted in bold. A linear regression model was used to determine the correlation between pAKT/AKT/ACTB and p110s/ACTB in GBM cell lines (D) or primary cells (E). R2 values denote the correlations of p110s and pAKT.

Among all 4 PI3K catalytic subunits, p110β was consistently expressed at high levels in some GBM cells (Fig. 3A, highlighted in bold). We therefore tested whether levels of p110β, but not other PI3K isoforms, correlated with AKT activation. Based on band intensities of p110 isoforms and pAKT normalized by total AKT and β-actin (Fig. 3B–C), high levels of p110β in GBM cell lines, primary cells, and GSC cells coincided with a robust activation of AKT and GSK3β (a downstream target of AKT) except VTC-034/GSCs and A172. In contrast, expression of other p110 isoforms failed to show this trend. VTC-034/GSCs expressed high levels of p110β, but low levels of pAKT and phosphorylated GSK3β (pGSK3β). The levels of GSK3β and pGSK3β were high in p110β-low A172 cells, possibly due to the uneven loading of total proteins.

Next, we used a linear regression model to quantitatively measure the correlations between levels of p110s and pAKT. We found that p110β levels in GBM cell lines showed the strongest correlation with pAKT levels (R2 = 0.79), whereas no or low correlations (Fig. 3D) were found between pAKT and other PI3K genes. Similar results were obtained in primary GBM cells and GSCs (Fig. 3E). Levels of pAKT were not significantly greater in PTEN-deficient cells than in PTEN–wild type cells (P = 0.06; Supplementary Figures S1 and S2A). While p110β levels were higher in PTEN-deficient cells (Supplementary Figure S2B), the correlation between p110β and pAKT decreased in PTEN-deficient cells (R2 = 0.66; Supplementary Figure S2C). These results suggest that p110β does not cooperate with PTEN deficiency to activate AKT in GBM. Together, our results suggest that PIK3CB/p110β is more important than other PI3K isoforms and PTEN in activating downstream AKT/GSK3β in GBM.

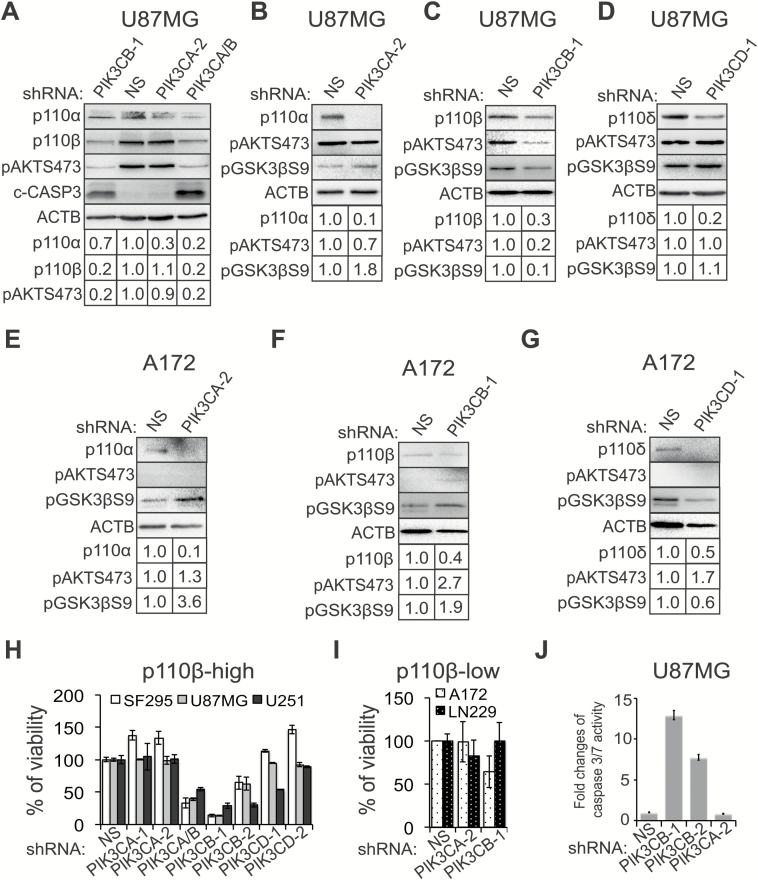

PI3K Catalytic Isoforms and GBM Cell Survival

We employed an shRNA-mediated knockdown to investigate whether PIK3CB/p110β is more important than other PI3K isoforms in promoting GBM cell survival. shRNAs of PIK3CA and PIK3CB decreased the levels of p110α and p110β by 70% and 80%, respectively (Fig. 4A). A nonselective shRNA that targets both PIK3CA and PIK3CB also efficiently depleted p110α and p110β. shRNAs of PIK3CB/p110β (ie, PIK3CB-1 or PIK3CA/B; Fig. 4A and 4C) significantly reduced levels of pAKTS473 and pGSK3βS9 in p110β/pAKT-high U87MG cells, whereas shRNAs of PIK3CA (Fig. 4B) or PIK3CD (Fig. 4D) did not inhibit AKT/GSK3β signaling. Inhibition of class IA PI3K catalytic isoforms increased, rather than decreased, the levels of pAKT and pGSK3β in p110β/pAKT-low A172 cells (Fig. 4E–G).

Fig. 4.

PIK3CB/p110β is important for the survival of GBM cells. (A) Knockdown of PIK3CA and PIK3CB in U87MG cells. Cells were treated with nonsilencing (NS) or shRNAs of PIK3CA and/or PIK3CB as indicated. pAKTS473 and cleaved caspase-3 (c-CASP3) that shows levels of apoptosis were also detected. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software. (B‒D) AKT/GSK3β signaling in U87MG cells with knockdown of PIK3CA, PIK3CB, or PIK3CD. (E‒G) AKT/GSK3βS9 signaling in A172 cells with depletion of PIK3CA, PIK3CB, or PIK3CD. (H) Cell viability in p110β-high GBM cell lines (U87MG, SF-295, and U251) upon depletion of PIK3CA, PIK3CB, or PIK3CD. Cell viability was determined using the MTS assay. (I) Viability of A172 and LN229 cells upon depletion of PIK3CA or PIK3CB. (J) Apoptosis in U87MG cells when PIK3CA or PIK3CB was knocked down. Apoptosis was measured using the caspase-3/7 activity assay. Error bars represent standard deviations from 3 independent experiments. Actin (ACTB) is the loading control for immunoblotting.

We next monitored cell survival by depleting PIK3CA, PIK3CB, or PIK3CD using 2 different shRNAs in p110β/pAKT-high SF-295, U87MG, and U251 cells. shRNAs of PIK3CB (PIK3CA/B, PIK3CB-1, and PIK3CB-2) caused a significant reduction of viability in these cells, whereas shRNAs of other PI3K isoforms had no or limited effect (Fig. 4H). In contrast, depletion of PI3K isoforms in p110β/pAKT-low A172 and LN229 cells failed to repress cell growth (Fig. 4I). Knockdown of p110 proteins in these cells was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4A–G and Supplementary Figure S3). Blocking PIK3CB/p110β in U87MG cells activated apoptosis as indicated by the elevated levels of cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 4A) and increased activity of caspase-3/7 (Fig. 4J). Our results together demonstrate that PIK3CB/p110β is selectively important for the survival of GBM cells highly expressing this protein.

Based on the above results, we hypothesized that p110β protein levels correlate with GBM patient survival. We divided 8 patient samples into low or high groups according to the levels of p110β and pAKT proteins (Fig. 3A) and compared their clinical survival rates. We found that p110β/pAKT-high patients had a much shorter lifespan than p110β/pAKT-low patients (P = 0.011; Supplementary Table S1), similar to the results of p110β mRNAs (Table 1). These results led us to further hypothesize that p110β/pAKT-high cells grow faster than p110β/pAKT-low cells. By using the MTS assay, which determined the cell number (R2 = 1.0; Supplementary Figure S4A), we verified that p110β/pAKT-high VTC-002 and VTC-103 cells grew more rapidly than p110β/pAKT-low VTC-056 cells (Supplementary Figure S4B). These results underscore the importance of PIK3CB/p110β in GBM cell survival and growth.

PI3K Isoform-Selective Inhibitors as a New Treatment for GBM

The results described above strongly suggest that selectively inhibiting PI3K isoforms, particularly PIK3CB/p110β, is a more effective therapeutic approach. To test this, we measured the cytotoxicity of isoform-selective PI3K inhibitors at various doses in p110β/pAKT-high U87MG and SF-295 as well as p110β/pAKT-low A172 and LN229 GBM cells. To provide a better comparison among these inhibitors, we determined their IC50 values. Consistent with the results of shRNA-mediated knockdown (Fig. 4), p110β inhibitors GSK2636771 and TGX-221 significantly suppressed the growth of p110β-high U87MG and SF-295 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). Their values of IC50 were below 20 μM. In contrast, these 2 compounds had no or modest effect on the viability of A172 and LN229 cells with IC50 values of 46.1 to 140.6 μM, respectively. Inhibitors of p110α, p110δ, or p110γ showed no selective cytotoxicity. For instance, PIK-75 (a p110α inhibitor) induced a remarkable growth inhibition in all 4 GBM cells expressing different levels of p110α with IC50 values from 0.1 to 0.3 μM, whereas another p110α inhibitor, BYL719, inhibited cell viability more strongly in p110α-low SF-295 and LN229 cells than in p110α-high U87MG and A172 cells (Fig. 5B). The p110δ inhibitor CAL101 exhibited no growth inhibition in all 4 GBM cells and PI3065 effectively suppressed the viability in p110δ-high U87MG and p110δ-low LN229 cells with an IC50 of 5.1 and 8.7 μM, respectively (Fig. 5C). The 110γ inhibitor CZC24832 promoted, rather than inhibited, the growth of U87MG and A172 (Supplementary Figure S5). Similar results were found in other p110α- or δ-selective inhibitors (ie, HS173 and IC87114; Supplementary Table S2). To exclude the possibility of a direct effect of p110β inhibitors on mitochondria rather than cell viability, we counted cell number using the trypan blue exclusion assay. Consistent results were observed (Supplementary Figure S6). We also tested primary GBM cells expressing different levels of p110β/pAKT. Congruently, TGX-221 exhibited a stronger cytotoxicity to p110β-high VTC-103 than to p110β-low VTC-001 cells with an IC50 of 13.4 or 32.7 μM, respectively (Fig. 5D). BYL719 (Fig. 5E) was more potent than CAL101 (Fig. 5F) in repressing the growth of VTC-001 and VTC-103 cells where p110α and p110δ were barely detected (Fig. 3A, middle panel). Possibly because of low levels of pAKT/pGSK3β, TGX-221 failed to inhibit the viability of p110β-high VTC-034/GSCs (Supplementary Figure S7). Consistently, constitutive activation of PI3K/AKT signaling by a PIK3CA mutant E545K antagonized TGX-221–induced growth inhibition in U87MG cells (Supplementary Figure S8). Hence, PI3K/AKT signaling activated by p110β determines the sensitivity of p110β-high GBM cells to p110β inhibitors.

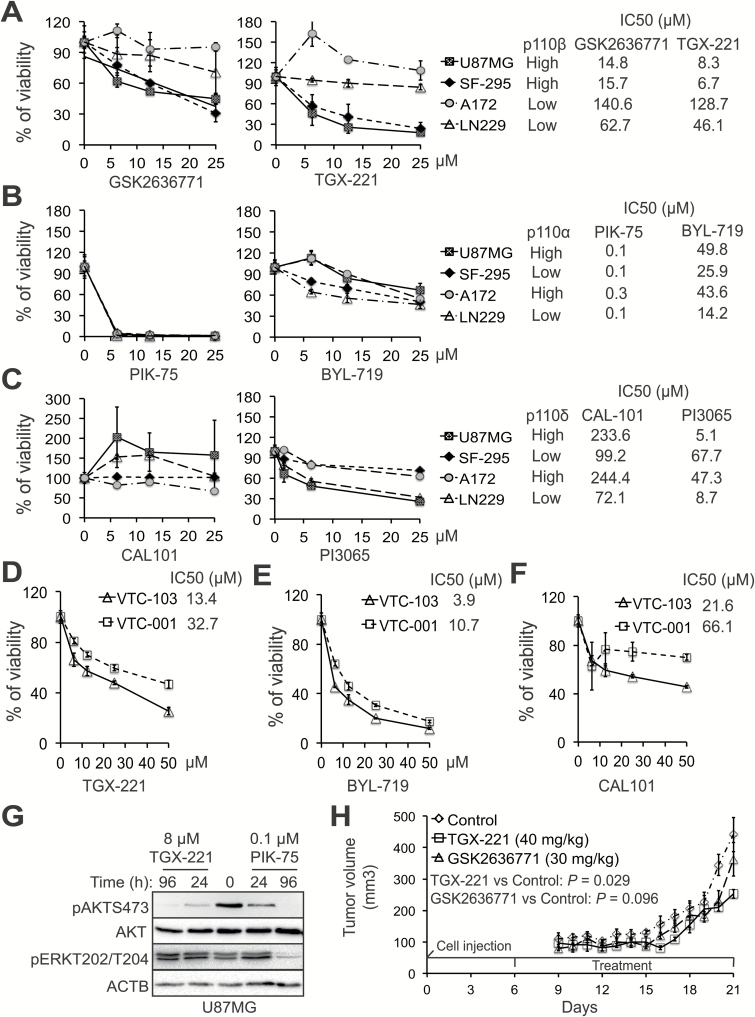

Fig. 5.

PIK3CB/p110β inhibitors selectively suppress the growth of p110β-high GBM cells in vitro and in vivo. Four GBM cell lines that express different levels of class I PI3K genes were treated with selective inhibitors of p110β (A), p110α (B), or p110δ (C). Cell viability was measured using the MTS viability assay. IC50 values (μM) of inhibitors are shown. Cytotoxic effect of TGX-221 (D), BYL719 (E), or CAL101 (F) was measured in primary p110β-high or p110β-low GBM cells. IC50 values are shown. (G) Activity of AKT and ERK in U87MG cells treated with TGX-221 or PIK-75 for 24 or 96 hours. (H) The growth of U87MG xenografts in mice treated with TGX-221 (40 mg/kg, i.p./daily) or GSK2636771 (30 mg/kg, i.p./daily). Error bars represent standard errors from 4 or 5 tumors. Significance of means between the control group and the treatment group (P-values of t-test) are shown. The time points of cell injection and treatment are indicated.

To test the specificity of PI3K inhibitors, we monitored the activity changes of AKT and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in U87MG cells treated with TGX-221 or PIK-75. ERK is another important cell survival pathway in GBM.19 TGX-221 induced a stronger inhibition of AKT activity than PIK-75 in 24 hours, although both drugs completely blocked AKT phosphorylation in 96 hours. We also found that PIK-75 significantly suppressed the activation of ERK at 96 hours in contrast to no inhibition of ERK by TGX-221 (Fig. 5G). Hence, TGX-221 is more selective than PIK-75 in inhibiting AKT. We also determined the cytotoxicity of drugs that target all PI3K isoforms (pan PI3K inhibitors) or PI3K/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) duo inhibitors. The pan PI3K inhibitors BKM120 and ZSTK474 blocked the viability of pAKT-high U87MG and pAKT-low LN229 without affecting the growth of pAKT-high SF-295 and pAKT-low A172 cells (Supplementary Figure S9). PI3K/mTOR duo inhibitors (PKI587 and LY294002) nonselectively blocked the growth of all 4 GBM cells (Supplementary Table S2).

We also determined the cytotoxicity of PI3K inhibitors to human astrocytes. We found that p110β inhibitors GSK2636771 and TGX-221 (IC50 = 110.4 and 291 μM, respectively) and the p110δ inhibitor CAL101 (IC50 = 122 μM) were much less toxic to astrocytes than other PI3K inhibitors (IC50 values ranging from 0.1 to 21.9 μM; Supplementary Table S3). Because p110β-high astrocytes expressed low levels of pAKT/pGSK3β (Fig. 3A), astrocytes did not respond effectively to p110β inhibitors (Supplementary Table S3).

To determine the therapeutic potential of p110β inhibitors in vivo, we used U87MG and SF-295 subcutaneous xenograft models. With a 2-week period of daily treatment (from day 6 to day 20), TGX-221 (40 mg/kg) significantly decreased the U87MG tumor volumes compared with the control vehicle with a P-value of 0.029 (Fig. 5H). The other p110β inhibitor, GSK2636771 (30 mg/kg), exhibited a marginal inhibition of tumor growth (P = 0.096; Fig. 5H). Similarly, TGX-221 significantly reduced the growth of SF-295 tumors (P = 0.036; Supplementary Figure S10).

Taken together, our results demonstrate that p110β inhibitors selectively suppress the survival/growth of p110β-high GBM cells with minimal/limited cytotoxicity to normal brain cells. Our in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrate that both TGX-221 and GSK2636771 inhibit GBM cell viability and retard tumor growth. Hence, p110β inhibitors have important clinical implications for GBM.

Implications in GBM Recurrence

GBM recurrence is inevitable, mostly because recurrent GBMs are refractory to TMZ, a DNA alkylating agent that induces DNA damage and cell death. Circumventing TMZ resistance will greatly improve clinical outcomes, thereby reducing chances of tumor recurrence. PI3K inhibitors have shown a promising effect on sensitizing GBM cells to TMZ.20 However, these chemical compounds are pan PI3K or PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitors, which often yield significant side effects as discussed above.21 Our research demonstrates that PIK3CB defines GBM patients with higher chances of tumor recurrence. In line with the modest efficacy of the p110β inhibitor GSK2636771 in mice, it is therefore necessary to test the drug effect of a combination of p110β inhibitors and TMZ (or other therapies, such as radiation) in treating GBM.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Neuro-Oncology online.

Funding

This work is supported by start-up funds from Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and a research grant from the Elsa U. Pardee Foundation to Z.S.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all members of the Sheng and Kelly laboratories for their advice and guidance on this project. The authors also thank patients with GBM at Carilion Clinic for their donation of tissue samples to our research.

References

- 1. Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Xu J et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2009–2013. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(Suppl 5):v1–v75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumor and Radiotherapy Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gallego O. Nonsurgical treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(4):e273–e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Varghese RT, Liang Y, Guan T, Franck CT, Kelly DF, Sheng Z. Survival kinase genes present prognostic significance in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7(15):20140–20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thorpe LM, Yuzugullu H, Zhao JJ. PI3K in cancer: divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(1):7–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Jones RG et al. Function of PI3Kgamma in thymocyte development, T cell activation, and neutrophil migration. Science. 2000;287(5455):1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wee S, Wiederschain D, Maira SM et al. PTEN-deficient cancers depend on PIK3CB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(35):13057–13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Opel D, Westhoff MA, Bender A, Braun V, Debatin KM, Fulda S. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibition broadly sensitizes glioblastoma cells to death receptor- and drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):6271–6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pu P, Kang C, Zhang Z, Liu X, Jiang H. Downregulation of PIK3CB by siRNA suppresses malignant glioma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2006;5(3):271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen H, Mei L, Zhou L et al. PTEN restoration and PIK3CB knockdown synergistically suppress glioblastoma growth in vitro and in xenografts. J Neurooncol. 2011;104(1):155–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hu P, Li B, Zhang W et al. AcSDKP regulates cell proliferation through the PI3KCA/Akt signaling pathway. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Höland K, Boller D, Hagel C et al. Targeting class IA PI3K isoforms selectively impairs cell growth, survival, and migration in glioblastoma. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanabur P, Guo S, Simonds GR et al. Patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells respond differentially to targeted therapies. Oncotarget. 2016;7(52):86406–86419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo S, Liang Y, Murphy SF et al. A rapid and high content assay that measures cyto-ID-stained autophagic compartments and estimates autophagy flux with potential clinical applications. Autophagy. 2015;11(3):560–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pohlmann ES, Patel K, Guo S, Dukes MJ, Sheng Z, Kelly DF. Real-time visualization of nanoparticles interacting with glioblastoma stem cells. Nano Lett. 2015;15(4):2329–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Murphy SF, Varghese RT, Lamouille S et al. Connexin 43 inhibition sensitizes chemoresistant glioblastoma cells to temozolomide. Cancer Res. 2016;76(1):139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reardon DA, Rich JN, Friedman HS, Bigner DD. Recent advances in the treatment of malignant astrocytoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(8):1253–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455(7216):1061–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dunn GP, Rinne ML, Wykosky J et al. Emerging insights into the molecular and cellular basis of glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2012;26(8):756–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prasad G, Sottero T, Yang X et al. Inhibition of PI3K/mTOR pathways in glioblastoma and implications for combination therapy with temozolomide. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(4):384–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fruman DA, Rommel C. PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(2):140–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.