Rare Mendelian disorders increasingly contribute to our understanding of the genetic architecture of autoimmune disease and the key molecular pathways governing its pathogenesis. Early-onset autoimmune disease can arise through activating mutations in inflammatory signalling pathways or loss-of-function mutations in immunoregulatory proteins.

We investigated the molecular basis of complex autoimmunity—characterised by the onset of insulin-dependent diabetes, cytopaenias, hepatitis, enteropathy and interstitial lung disease at age 10—in a 14-year-old boy of healthy non-consanguineous British parents. Immunological analysis revealed lymphopaenia with no naive T cells and a high proportion of activated T cells (table 1). Pathogenic variants in STAT3 and FOXP3 were excluded. The clinical course was refractory to intensive immunosuppression with prednisolone, sirolimus, tacrolimus, infliximab or rituximab, necessitating haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Twenty-one months post-transplant, he is thriving off all immunosuppressive medication with complete remission of autoimmune disease (except diabetes).

Table 1.

Immunological and clinical parameters

| Parameters | Pretransplant | Post-transplant | Reference range |

| Laboratory | |||

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 9.8 | 12.4 | 13.5–17.5 |

| Leucocytes (109/L) | 1.88 | 3.47 | 150–450 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 0.17 | 1.31 | 1.2–5.2 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 1.52* | 1.79 | 1.8–8.0 |

| Monocytes (109/L) | 0.19 | 0.37 | 0.2–0.8 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 29 | 183 | 150–400 |

| CD3+ (cells/µL) | 800 | 1914 | 800–3500 |

| CD8+ (cells/µL) | 554 | 936 | 200–1200 |

| CD4+ (cells/µL) | 238 | 920 | 400–1200 |

| CD56+ (cells/µL) | 35 | 99 | 70–1200 |

| CD19+ (cells/µL) | 138 | 99 | 200–600 |

| Activated T cells (HLA-DR+ %) |

55 | 25 | N/A |

| CD4+ naive (%) | Not detected | 244 | N/A |

| CD27– IgD+ (naive) (%) | 87 | 93 | 75.2–86.7 |

| CD27+ IgD+ (memory) (%) | 9 | 4 | 4.6–10.2 |

| CD27+ IgD– (class-switched) (%) |

2 | 3 | 3.3–9.6 |

| IgM (g/L) | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.50–1.90 |

| IgG (g/L) | 6.4 | 8.2 | 5.4–16.1 |

| IgA (g/L) | 0.92 | 0.33 | 0.80–2.80 |

| Tetanus (IU/mL) | 0.93 | ND | 0.1–10 |

| Haemophilus influenzae b (mg/mL) | 1.8 | ND | 1.0–20.0 |

| Pneumococcal (mg/mL) | 10 | ND | 20–200 |

| Anti-GAD antibody (IU/mL) | >2000 | >2000 | 0–9.9 |

| Islet cell antibody | Detected | Detected | N/A |

| pANCA | Detected | Detected | N/A |

| Clinical | |||

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 38 | 84 | 95–100 |

*Peripheral neutrophils were supported pretransplant by recombinant granulocyte colony stimulating factor. Post-transplant parameters were obtained at 18 months (FBC and T-cell indices, lung function) or 21 months post-HSCT (B cell and antibody indices). Post-HSCT antibody indices were measured during concomitant subcutaneous immunoglobulin supplementation. No other autoantibodies were detected pre-HSCT or post-HSCT.

FBC, full blood count; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; GAD, glutamic acid decarboxylase; HLA-DR, human leucocyte antigen–antigen D related; HSCT, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ND, not done; pANCA, perinuclear anti neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.

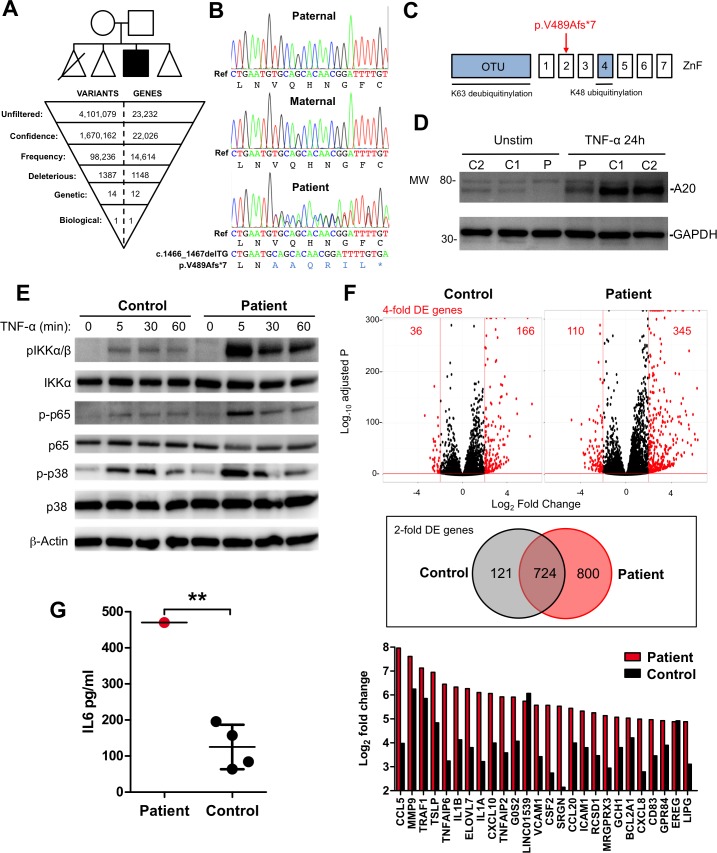

Ethical approval was granted (ref: 10/H0906/22) and written informed consent provided prior to study commencement. By whole exome sequencing of peripheral blood genomic DNA (Illumina MiSeq) and downstream bioinformatic filtering (Ingenuity Variant Analysis), we identified a single biologically plausible variant—a novel de novo heterozygous 2 bp deletion in tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, figure 1A). TNFAIP3 encodes the ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20, a negative regulator of the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway.1 A20 removes K63-linked ubiquitin chains from key adaptor proteins, replacing them with K48-linked polyubiquitin chains, to trigger proteasomal degradation and termination of the NF-κB activation cascade.2 Polymorphisms in TNFAIP3 have been linked to the development of several autoimmune diseases in genome-wide association studies.3–7 A conditional knockout of A20 in immune cells leads to the development of autoimmunity in the mouse.8 However, autoimmune phenomena were not prominent in a recently described cohort of patients with germline A20 haploinsufficiency, who instead presented with an autoinflammatory phenotype resembling Behçet’s disease.9

Figure 1.

TNFAIP3 variant identification and functional validation. (A) The family pedigree is shown (triangles are used to preserve the anonymity of healthy unaffected siblings). The first-born infant died as a result of prematurity. Whole exome sequencing data were filtered (Ingenuity Variant Analysis) by confidence (call quality ≥20; read depth ≥10; allele fraction ≥45%); frequency (ExAc allele frequency ≤0.01%); deleteriousness (nonsense/deleterious missense (SIFT/PolyPhen), splice-site disruption); genetic segregation (ie, present in patient and absent from 47 unrelated disease controls) and biological function (linked to phenotype), identifying a single heterozygous frameshift variant in TNFAIP3 (c.1466_1467TGdel). (B) Variant confirmation by Sanger sequencing. (C) The c.1466_1467TGdel variant resulted in a frameshift and premature stop codon (V489Afs*7) in the second ZnF domain and is distinct from previously described mutations in the OTU and ZnF4 domains (blue). (D) V489Afs*7 reduced basal and TNF-induced A20 protein in patient (P) versus control (C1, C2) fibroblasts (immunoblot representative of n=4 independent experiments with n=4 controls). (E) Signalling responses downstream of TNF-α stimulation in patient fibroblasts were exaggerated and prolonged compared with control (immunoblot representative of n=4 independent experiments with n=4 controls). (F) RNA-seq analysis of transcriptional response to 6-hour TNF-α stimulation in patient and control fibroblasts (stimulations performed in triplicate in a single experiment). Top panel: displayed in red are significant (FDR-corrected p≤0.01) DE transcripts regulated ≥4 fold (≥2log2-fold); middle panel: Venn diagram displaying all overlapping DE transcripts ≥2 fold (≥log2-fold); Bottom panel: top 20 significant DE transcripts in patient (red bars) versus control (black bars), demonstrating many major NF-κB target genes. (G) Levels of IL-6 quantified by ELISA in supernatants from patient and control fibroblasts stimulated with TNF-α for 24 hours (mean±SD of average values from two independent experiments in patient and n=4 controls compared by one-sample t-test; **p=0.0015). DE, differentially expressed; FDR, false discovery rate; IL-6, interleukin 6; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; OTU, ovarian tumour; PolyPhen, polymorphism phenotyping; SIFT, Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-alpha; TNFAIP3, tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 3; ZnF, zinc finger.

The c.1466_1467delTG variant—which we confirmed by capillary sequencing10 (figure 1B)—introduces a frameshift substitution of alanine for valine at position 489, generating a downstream premature stop codon (p.V489Afs*7) in the zinc finger (ZnF)2 domain of A20. This variant is absent from public databases (ExAc/dbSNP) and distinct from disease-associated mutations affecting the ovarian tumour or ZnF4 domains of A209 (figure 1C). Immunoblotting10 of patient and control dermal fibroblast lysates with an N-terminal antibody confirmed the reduced basal and TNF-α-induced expression of A20 (figure 1D).

To address the consequence of this reduced A20 expression, we performed functional experiments in patient and control dermal fibroblasts. Initially, we stimulated these cells with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) and analysed downstream signalling events by immunoblot (figure 1E). We observed exaggerated and prolonged phosphorylation of components of the NF-κB pathway, which would be expected to enhance NF-κB-dependent transcriptional effects. In keeping with this prediction, RNA sequencing (Illumina NextSeq-500) revealed a significant global increase in both the range and magnitude of TNF-α-stimulated differential gene expression (fold-change ≥2; false discovery rate-adjusted p≤0.01, figure 1F). We also confirmed enhanced expression of the key NF-κB target gene interleukin 6 (IL-6) at the protein level by ELISA (p=0.0015, figure 1G). In these respects, the molecular consequences of the p.V489Afs*7 variant were indistinguishable from reported pathogenic A20 mutations,9 although owing to the lack of leucocyte material, we were not able to extend our analysis to inflammasome activation.

Here we provide novel validation of considerable existing evidence that implicates TNFAIP3 in autoimmune pathogenesis. This case expands the clinical spectrum of A20 haploinsufficiency.9 As A20 regulates multiple innate and adaptive signalling pathways,1 it is logical that patients with inactivating mutations in A20 might manifest pathological features of autoimmunity and/or autoinflammation. Finally, we report that correction of the molecular defect within the haematopoietic cell compartment could represent a viable treatment option for severe clinical manifestations.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient and their family for their trust and assistance. They are grateful to colleagues in St. James’ Hospital, Leeds and Great North Children’s Hospital, Newcastle for providing clinical care. They thank R. Harry, N. Maney, J. Isaacs and A. Pratt for the kind gift of reagents.

Footnotes

CJAD, ED and RT contributed equally.

Contributors: CJAD, KRE and SH: designed research. MFT, JT, VZ, MAS, AJC and SH: clinical investigation and phenotyping. CJAD, ED, RT, AG, JDPW and DJS: performed experiments. CJAD, ED, RT, AJS, KRE and SH: analysed and interpreted data. CJAD and AJS: performed statistical analysis; CJAD and SH: wrote the manuscript. All authors: reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding: CJAD was supported by the Academy of Medical Sciences (AMS-SGCL11), the British Infection Association and the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR); JDPW, DJS, KRE and SH were supported by the Sir Jules Thorn Trust (12/JTA); AG was supported by the Bubble Foundation; AJS was supported by the MRC-Arthritis Research UK Centre for Integrated research into Musculoskeletal Ageing (CIMA) and NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: NHS North East-Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 REC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: RNA-Seq data have been submitted to GEO (ref: GSE95078). Details of Sanger sequencing primers and the Ingenuity Variant Analysis bioinformatic filtering strategy are available on request.

References

- 1. Catrysse L, Vereecke L, Beyaert R, et al. A20 in inflammation and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol 2014;35:22–31. 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wertz IE, Newton K, Seshasayee D, et al. Phosphorylation and linear ubiquitin direct A20 inhibition of inflammation. Nature 2015;528:370–5. 10.1038/nature16165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet 2008;40:1059–61. 10.1038/ng.200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Musone SL, Taylor KE, Lu TT, Tt L, et al. Multiple polymorphisms in the TNFAIP3 region are independently associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet 2008;40:1062–4. 10.1038/ng.202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fung EY, Smyth DJ, Howson JM, et al. Analysis of 17 autoimmune disease-associated variants in type 1 diabetes identifies 6q23/TNFAIP3 as a susceptibility locus. Genes Immun 2009;10:188–91. 10.1038/gene.2008.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lodolce JP, Kolodziej LE, Rhee L, et al. African-derived genetic polymorphisms in TNFAIP3 mediate risk for autoimmunity. J Immunol 2010;184:7001–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Musone SL, Taylor KE, Nititham J, et al. Sequencing of TNFAIP3 and association of variants with multiple autoimmune diseases. Genes Immun 2011;12:176–82. 10.1038/gene.2010.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tavares RM, Turer EE, Liu CL, et al. The ubiquitin modifying enzyme A20 restricts B cell survival and prevents autoimmunity. Immunity 2010;33:181–91. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou Q, Wang H, Schwartz DM, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in TNFAIP3 leading to A20 haploinsufficiency cause an early-onset autoinflammatory disease. Nat Genet 2016;48:67–73. 10.1038/ng.3459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Duncan CJ, Mohamad SM, Young DF, et al. Human IFNAR2 deficiency: Lessons for antiviral immunity. Sci Transl Med 2015;7:307ra154 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]