Abstract

The objective of this review was to examine the prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) in individuals with COPD. A computer-based literature search of CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO and Embase databases was performed. Studies reporting the prevalence of OA among a cohort of individuals with COPD were included. The sample size varied across the studies from 27 to 52,643 with a total number of 101,399 individuals with COPD recruited from different countries. The mean age ranged from 59 to 76 years. The prevalence rates of OA among individuals with COPD were calculated as weighted means. A total of 14 studies met the inclusion criteria with a prevalence ranging from 12% to 74% and an overall weighted mean of 35.5%. Our findings suggest that the prevalence of OA is high among individuals with COPD and should be considered when developing and applying interventions in this population.

Keywords: COPD, osteoarthritis, prevalence, comorbidities, pulmonary rehabilitation

Introduction

COPD is characterized by symptoms of dyspnea and reduced exercise tolerance.1 It is widespread globally and destined to become the third most common cause of mortality within the next few years.2,3 COPD is a leading cause of disability.4,5 Although the primary pathophysiology is respiratory in COPD, several secondary impairments and co-occurring cardiovascular, metabolic and musculoskeletal conditions have been noted.6–14 Inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, prescribed corticosteroids, hypoxemia and hypercapnia all contribute to the extra-pulmonary manifestations such as cardiovascular compromise, osteoporosis and muscle dysfunction.15,16

An important co-occurring condition is osteoarthritis (OA), a degenerative joint disease characterized by damaged articular cartilage, bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, muscle weakness and ligamentous damage.17,18 OA is also a widely prevalent cause of disability, which is responsible for chronic pain and diminished exercise tolerance.19–21 Many risk factors for OA include age, weight, being female, ethnicity, previous joint injury or repetitive use, muscle weakness and joint laxity.22

As both COPD and OA diminish physical activity and increase the time spent in sedentary behavior,1,23 the co-occurrence of these two conditions is important as both promote decreased participation and a diminution in health-related quality of life.24–26 Notwithstanding the abovementioned information, there is very limited information regarding the prevalence of OA among those with COPD. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review to estimate the mean prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD.

Methods

The review protocol followed PRISMA guidelines27 and was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017055795).

Search strategy and study selection

A systematic computerized literature search of Medline, CINAHL, Embase and PsycINFO databases was carried out with the timescale starting from their inception up to April 2017. The keywords used to carry out the search were as follows: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (MeSH), osteoarthritis (MeSH) and prevalence (MeSH). The detailed search strategy for each database is provided in the Supplementary materials.

We included studies reporting the prevalence of OA in a cohort of individuals with COPD. Articles where individuals with COPD could not be isolated from the overall sample or where OA could not be distinguished from other comorbidities (such as rheumatoid arthritis) were excluded. Articles that reported the co-occurrence of COPD and OA without referring to the main diagnosis and comorbidity were also excluded.

Case–control, cohort, cross-sectional and interventional studies that reported the prevalence of OA as a comorbidity in a sample of individuals with COPD were included, while conference articles, editorials and non-English articles were excluded. Reviews were excluded, although their reference lists were searched manually for potentially relevant articles.

Data collection and analysis

Data extraction was performed by two reviewers (AW, DB). The data extracted were the following: full citation, type of study, country of origin of the study, sample size (of individuals with COPD), mean and SD of the age of the sample, percentage of females included, the races/ethnicities of the population examined, percentage of overweight and/or obese individuals, smoking status and percentage of OA among the sample. The three factors, age, sex and obesity, are common to both diseases. Prevalence rates of OA in individuals with COPD were calculated as weighted means, whereby the sample size of each study was multiplied by the corresponding prevalence rate and divided by the total sample size of all the studies. The overall mean prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD was the sum of the weighted means. A similar methodology was performed previously elsewhere.28

During the screening process, it was evident that some studies examined patients from the same database. To avoid the bias that might be caused by the inclusion of multiple studies of the same cohort on the calculated prevalence mean, only the larger sample size study was included.

Assessment of study quality

Quality assessment of the included studies was undertaken according to the “checklist for prevalence studies” as suggested by the Joanna Briggs Institute.29 This tool consists of nine questions aimed at addressing the possibility of bias in the design, methods and analysis for studies that include prevalence data. The questions are self-explanatory and answers are as follows: yes, no, unclear or not applicable. Question 6 on methods was answered with “yes” if the diagnoses of both COPD and OA were based on diagnostic criteria. If the conditions (or one of them) were assessed using observer reported, or self-reported scales, then the question was answered by “no.” Question 7 on reliability of identifying the conditions was answered with “yes” only if both conditions were measured in the same way for all participants.29

Two researchers (DB, AW) conducted the quality assessment separately with any contestations being solved by discussion. The assessment of study quality had no impact on the inclusion or exclusion of the study.

Results

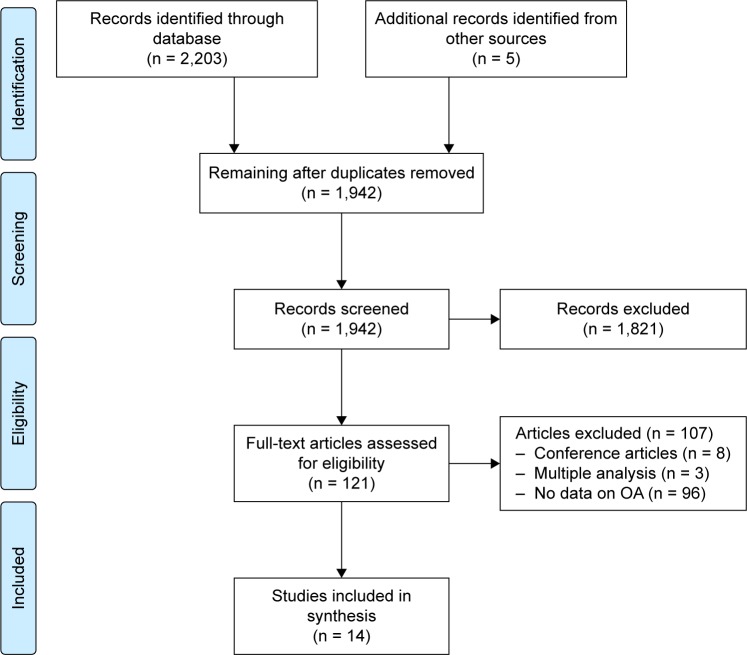

The search resulted in 2,203 articles being identified, of which 266 were duplicates. A total of 1,821 abstracts were excluded based on being unrelated to the topic.

Another 107 articles were excluded for various reasons, including the following: conference articles (eight articles); not including data on OA (92 articles); multiple analysis of the same patients (three articles). The manual search resulted in identifying five additional articles. The PRISMA flowchart from articles identified to those included is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the search and study selection.

Abbreviation: OA, osteoarthritis.

The articles included in the review and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Six studies30,33,35,38–40 were conducted on populations in the USA, and one study34 examined patients from nine countries. The remainder (published in English) were from the following: the Netherlands,31,41 UK,32,42 Korea,37 South Africa36 and Germany.43 Seven studies31,33,37–39,42,43 (50%) followed the observational cohort design; six30,32,34–36,41 were cross-sectional (43%) and only one40 (7%) was a case–control study. Studies varied in sample size39,42 (27–52,643) as well as age33,42 (59.3–76 years). In six studies,32–34,36,37,40 data on age and/or sex could not be extracted, and in five,33,36,40–42 data on obesity was unavailable. Seven studies31,33,34,36,39,41,42 out of 14 reported data on smoking status among their sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies with the timescale starting from the inception of the databases up to April 2017

| Article | Study type | Population | Method of identification | Country | Race | Mean age in years (SD) | Females | Obesity (%) | Smoking status | % OA reported | Weighted mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schnell et al30 | Cross- sectional | 995 with COPD from NHANES | Search | USA | % (95% CI): White: 84.6 (81.4–87.4); Black: 6.8 (5.1–8.9); Hispanic: 4.4 (3.0–6.3) | 62.7 (95% CI 61.7–63.8) | 60.1% | 40.3% | Ever smoked (68.9%); >10 pack-years (43%) | 54.6% | 0.54% |

| Westerik et al31 | Retrospective cohort study | 14,603 with COPD from health records in Dutch general practices | Search | the Netherlands | Not reported | 66.5 (SD 11.5) | 46.9% | 4.4% | Not reported | 17.6% | 2.53% |

| Rai et al32 | Cross- sectional | 608 with COPD out of 1,889 from Birmingham COPD cohort study | Manual search | UK | Not reported | Age: 38–49 (11.2%); 50–59 (41.6%); 60–64; (47.2%) | 43.6% | BMI (kg/m2): underweight (<18.5) = 2.8%; normal weight (18.5–24.9) = 26.8%; overweight (25.0–29) = 35.2%; obese (30.0–39) = 29.6%; morbidly obese (>40.0) = 5.7% | Current smokers (49.7%); ex-smokers (42.8%); never smoked (7.5%) | 16.8% | 0.10% |

| Lee et al33 | Cohort study | 15,540 with COPD (55–64 years) from National Veterans Health Administration database | Manual search | USA | Not reported | 59.3 (3.1) | Not reported (mostly males) | Not reported | Not reported | 20% | 3.07% |

| Garin et al34 | Cross- sectional study | 3,339 with COPD from 41,909 adults >50 years from nine countries | Search | Nine countries: China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Finland, Spain and Poland | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 19% | Not reported | 44% | 1.45% |

| Kumbhare et al35 | Cross- sectional, observational study | 4,807 with COPD from the 2012 BRFSS, an annual random digit-dialed telephone survey | Search | USA | White, non- Hispanic (82.9%); Black, non-Hispanic (8.2%); other race, non- Hispanic (3%); multiracial, non- Hispanic (2.8%); Hispanic (1.8%) | 67.1 (SD 11.8) | 61.6% | BMI (kg/m2) categories: underweight (<18.5) = 7%; normal weight (18.5–24.9) = 29.8%; overweight (25.0–29.9) = 30.9%; obese (30.0–39.9) = 26.3%; morbidly obese (>40.0) = 6.1% | Current smokers (34.3%); ex-smokers (45.5%); never smoked (20.2%) | 61.2% | 2.9% |

| Lalkhen and Mash36 | Cross- sectional study | 140 with COPD from primary health care facilities in South Africa | Search | South Africa | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 12.1% | 0.02% |

| Park et al37,* | Retrospective cohort | 1,905 with COPD from the database of the fourth and fifth (2007–2012) KNHANES | Search | Korea | Not reported | 64.5 (10.2) | 32% | BMI (kg/m2) categories (<18.5) = 3.3%; (18.5–23.0) = 68.2%; (≥23.0) = 28.5% | Current smokers (39.6%); ex-smokers (17.6%); never smoked (42.8%) | 11.9% | 0.22% |

| Putcha et al38 | Cohort study | 3,690 African- Americans and non-Hispanic Whites among GOLD 2–4 COPD patients | Search | USA | African- Americans (23%); non- Hispanic Whites (77%) | 63.4 (8.5) | 44% | Mean BMI (SD) 28.1 (6.3) | Current smokers (40.7%) | 20.7% (calculated not reported) | 0.75% |

| Schwab et al39 | Retrospective cohort study | 52,643 with COPD from US claims database (Humana Inc., Louisville, KY, USA) | Search | USA | Not reported | 70.6 (9.6) | 55% | 19.65% | Not reported | 43.8% | 22.7% |

| Mapel et al40,** | Case–control study | 200 with COPD from 1,522 from the Managed Care Database, New Mexico | Manual search | USA | Hispanic (17.8%); non- Hispanic (82.2%) | 67.5 | 48.9% | Not reported | Current smokers (46%); ex-smokers (34%); never smoked (14.5%) | 22% (moderate- to-severe arthritis only) | 0.04% |

| Wijnhoven et al41 | Cross- sectional study | 161 with COPD from 25 primary care practices in the Netherlands | Manual search | the Netherlands | Not reported | 61 (10.3) | 44.7% | Not reported | Not reported | 23% | 0.04% |

| Yeo et al42 | Observational cohort study | 27 with COPD ≥70 years from the UK primary care | Manual search | UK | Not reported | 76 (4.36) | 40.7% | Not reported | Not reported | 74% | 0.02% |

| Karch et al43 | Cohort study | 2,741 with COPD from 31 centers in Germany | Manual search | Germany | Not reported | 65.1 (8.6) | 41% | Mean BMI (SD) 27.0 (5.4) | Current smokers (24%); ex-smokers (68%); never smoked (8%) | 40.1% | 1.08% |

| Total = 101,399 | Total = 35.5% |

Notes:

The characteristics of the percentage of males and the mean age are for the overall sample in the original study (n = 2,108) not for the patients included in our analysis (n = 1,905).

The characteristics of the percentage of males and the mean age are for the overall sample in the original study (n = 1,522) not for the patients included in our analysis (n = 200). Smoking history not documented for 5.5% of the patients.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; KNHANES, Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NHANES, National Health and Nutritional Examination Study; OA, osteoarthritis; GOLD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease scale.

The prevalence of OA varied across the studies from 11.9%37 to 74%,42 and the weighted mean of the prevalence of OA varied from 0.02%36,42 to 22.7%.39 The overall weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD for the 14 identified studies was 35.5%.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The quality assessment results are illustrated in Table 2. A total of 10 articles (71%) used self-reported diagnosis to diagnose COPD and OA. In 11 studies (79%), the question regarding the adequacy of response rate was marked as not applicable as the studies were observational with information extracted from databases (Table 2).

Table 2.

The quality assessment results for the included articles starting from the inception of the databases to April 2017

| Article | 1. Sample frame appropriate to target population? | 2. Study participants sampled in an appropriate way? | 3. Sample size adequate? | 4. Study subjects and setting described in detail? | 5. Analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? | 6. Valid methods to identify condition? | 7. Condition measured in a standard, reliable way? | 8. Appropriate statistical analysis? | 9. Response rate adequate or was low response rate managed appropriately? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schnell et al30 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Westerik et al31 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Rai et al32 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Lee et al33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Not applicable |

| Garin et al34 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Kumbhare et al35 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Lalkhen and Mash36 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | No | Unclear | Not applicable |

| Park et al37 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Putcha et al38 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Schwab et al39 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Mapel et al40 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

| Wijnhoven et al41 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Yeo et al42 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Karch et al43 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Not applicable |

We calculated the weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD in 10 articles in which COPD and/or OA were self-reported and in the four studies in which COPD and/or OA were measured objectively, and noted prevalence rates of 30.7% and 37.6%, respectively.

Discussion

This is the first article that systematically examined the prevalence of OA in individuals with COPD. In a sample of more than 100,000 individuals with COPD, we noted prevalence rates ranging from 12% to 74% across the studies with a weighted average of 35.5%. The wide ranges of the prevalence rates might well be explained by the heterogeneity of the study designs, cohort characteristics, sample size and method of sampling. In some studies, COPD was diagnosed without spirometric confirmation, and in others, OA was not confirmed radiologically. Prevalence results vary quite substantially. For example, Yeo et al42 in an observational study of a cohort of only 27 older (aged >70 years) individuals with COPD drawn from a single primary care practice reported that 74% of their sample had OA. In contrast, Park et al,37 reporting on the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) study, nationally designed to assess the health of community-dwelling adults, found a prevalence rate of knee or hip joint OA (defined as Kellgren–Lawrence grade ≥2) in only 12% of individuals with COPD (n = 1,905; mean age = 65 years). The study by Schwab et al,39 mean age 70.6 years (9.6), represented the greatest contribution to the overall weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD (23%) because of its large sample size of 52,643.

Smoking status varied significantly across the studies. These differences add to the heterogeneity noted in cohort characteristics and may have influenced the findings of this review. There is some evidence to suggest that smoking may be associated with a lower risk of developing OA,44–46 but it is unclear as to whether this observed inverse relationship between smoking and OA is direct (caused by smoking itself) or indirect (caused by the lower body mass index [BMI] associated with smokers compared to their nonsmoker peers).47 Of note, none of the included articles in this systematic review reported the prevalence of OA by smoking status.

Obesity is a major risk factor for OA.22 The prevalence rates of obesity reported by only six studies varied quite substantially from 4.4% to 40.3%. In the study by Schwab et al,39 less than one-fifth (19.65%) of the sample were obese.

Most studies (10/14) relied on self-reported questionnaires to establish a diagnosis with only four out of 14 articles using confirmatory diagnostic tests.33,37,39,40,48,49 Although the use of objectively measured vs self-reported identification of OA could impact reporting accuracy, the difference in the prevalence of OA among self-reported questionnaires and those objectively measured was not substantial (30.7% vs 37.6%).

The prevalence of OA in COPD may exceed that of the non-COPD population. For example, among more than 4,000,000 Canadians living in British Columbia,50 the prevalence of OA in 2001 was 10.8% and in a study51 conducted in Malmo, Sweden, among 10,000 adults (56–64 years) radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis was 25.4%. In the study by Framingham52 and the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project,53 both of which enrolled healthy adults, it was 19.2% and 27.8%, respectively. Notwithstanding study variations, we report a prevalence of OA in COPD of 35.5%.

Importantly, the shared risk factors between COPD and OA such as older age and female gender may increase the possibility of the co-occurrence of both conditions. In fact, Kopec et al50 noted that age is associated with an exponential increase in OA between the age group of 20 and 50 years and a linear increase between the age group of 50 and 80 years. None of the articles in this systematic review categorized OA in COPD by the age group. The mechanism whereby OA is prevalent in COPD, whether by increased systemic inflammatory mediators, reduced skeletal muscle function or an increase in physical inactivity, remains to be established.16,54–56

The increased prevalence of OA is not likely to be confined to COPD as it has been noted to occur frequently in other chronic conditions such as asthma, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease and depression.34 However, as both COPD and OA reduce mobility, an awareness of their co-occurrence will inform management programs such as pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) which aim to improve exercise capacity and health-related quality of life. Co-occurring conditions may adversely affect PR,57–60 and in a prospective study58 of 316 outpatients enrolled in PR, musculoskeletal comorbidities were identified in 10.2% of participants. Their exact impact on referral, participation and completion remains unclear especially as patients with severe comorbidities may be excluded from enrollment in an exercise training program.58 Of interest, notwithstanding detailed guidelines and statements on PR,61,62 there are no formal guidelines on the assessment and management of those with co-occurring conditions.

As PR programs move closer to being patient rather than disease focused, exercise training using endurance, resistance, flexibility and balance will be modified to focus on the specific impairments and activity limitations. For example, in the presence of lower limb comorbidities, aquatic exercise has been reported as being equally effective as land-based exercise in improving function. McNamara et al63 randomized 53 individuals with COPD and lower limb comorbidities to receive either land-based or aquatic exercise and reported similar improvements in 6-minute walking distance in both groups and greater improvements in incremental shuttle walk as well as fatigue in the aquatic group.

The findings of this systematic review support the development of new pharmacological approaches in this patient population. Both COPD and OA are associated with chronic systemic inflammation, and increased levels of neutrophil elastase have been noted in COPD.64–67 There is emerging evidence that neutrophil elastase is associated with articular tissue destruction in inflammatory joint diseases.68 Neutrophil elastase inhibitors, already used in the management of COPD, have been shown to have protective and reparative effects on joint inflammation.69 Therefore, the development of new pharmacologic approaches that might slow tissue destruction and promote repair would be of great benefit to the population with coexisting COPD and OA.

This review is limited by the heterogeneity of study designs and cohort characteristics. A number of articles were of poor quality, and only English language articles were included. It was not possible to obtain information regarding the location and severity of OA or its clinical impact. The results may have been biased toward one large study,39 which was responsible for approximately 23% of the overall calculated weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD. The observation that the weighted mean of the prevalence of OA in COPD in eight studies30,32,36–38,40–42 out of 14 was <1% suggests that only a few studies significantly contributed to the overall calculated average prevalence rate.

Conclusion

Accurate information on the prevalence of OA in COPD is limited by the heterogeneity of studies. However, it is a frequently co-occurring condition that an awareness of which will inform the way health care providers manage symptoms, mobility, participation and health-related quality of life in the COPD population.

Supplementary materials

Search strategies for each database

Search strategy for Medline and PsycINFO databases

lung diseases, obstructive/or bronchitis/or pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive/or bronchitis, chronic/or pulmonary emphysema/

COPD.tw

(chronic obstruct* pulmonary diseas* or chronic obstruct* respiratory diseas*).tw

1 or 2 or 3

osteoarthritis/or osteoarthritis, hip/or osteoarthritis, knee/or osteoarthritis, spine/

(osteoarthr* or arthr* or joint* degenerat*).tw

5 or 6

morbidity/or prevalence/

(common* or frequen* or comorbid* or multimorbid* or epidemio* or prevalen*).tw

8 or 9

4 and 7 and 10

Search strategy for Embase database

chronic obstructive lung disease/or obstructive airway disease/

copd.tw

(chronic obstruct* pulmonary diseas* or chronic obstruct* respiratory diseas*).tw

1 or 2 or 3

osteoarthritis/or arthritis/or degenerative disease/or osteoarthropathy/or experimental osteoarthritis/or hand osteoarthritis/or hip osteoarthritis/or knee osteoarthritis/or spondylosis/

(osteoarthr* or arthr* or joint* degenerat*).tw

5 or 6

prevalence/or epidemiological data/or epidemiology/

morbidity/

(common* or frequen* or comorbid* or multimorbid* or epidemio* or prevalen*).tw

8 or 9 or 10

4 and 7 and 11

Search strategy for CINAHL database

-

S1

(MH “Lung Diseases, Obstructive+”) OR (MH “Bronchitis”) OR (MH “Emphysema”) OR (MH “Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive+”) OR (MH “Bronchitis, Chronic”)

-

S2

COPD

-

S3

chronic obstruct* pulmonary diseas* OR chronic obstruct* respiratory diseas*

-

S4

S1 OR S2 OR S3

-

S5

(MH “Osteoarthritis, Hip”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis, Knee”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis+”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis, Spine+”) OR (MH “Osteoarthritis, Wrist”)

-

S6

osteoarthr* OR arthritis OR arthrosis OR joint* degenerat*

-

S7

S5 OR S6

-

S8

(MH “Prevalence”) OR (MH “Morbidity+”)

-

S9

common* or frequen* or comorbid* or multimorbid* or epidemi*

-

S10

S8 OR S9

-

S11

S4 AND S7 AND S10

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López-Campos JL, Tan W, Soriano JB. Global burden of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(1):14–23. doi: 10.1111/resp.12660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisner MD, Iribarren C, Blanc PD, et al. Development of disability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: beyond lung function. Thorax. 2011;66(2):108–114. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.137661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agusti À, Soriano J. COPD as a systemic disease. COPD. 2008;5(2):133–138. doi: 10.1080/15412550801941349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agusti AG, Noguera A, Sauleda J, Sala E, Pons J, Busquets X. Systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(2):347–360. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00405703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabit R, Bolton CE, Edwards PH, et al. Arterial stiffness and osteoporosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(12):1259–1265. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-067OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wouters E. Introduction: systemic effects in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(suppl 46):1s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00000103a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holguin F, Folch E, Redd SC, Mannino DM. Comorbidity and mortality in COPD-related hospitalizations in the United States, 1979 to 2001. Chest J. 2005;128(4):2005–2011. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holguin F. Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):962–969. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00012408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schols AM, Broekhuizen R, Weling-Scheepers CA, Wouters EF. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):53–59. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cielen N, Maes K, Gayan-Ramirez G. Musculoskeletal disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2014/965764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatila WM, Thomashow BM, Minai OA, Criner GJ, Make BJ. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):549–555. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-148ET. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corsonello A, Incalzi RA, Pistelli R, Pedone C, Bustacchini S, Lattanzio F. Comorbidities of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2011;17:S21–S28. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000410744.75216.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes P, Celli B. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2009;33(5):1165–1185. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maltais F, Decramer M, Casaburi R, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(9):e15–e62. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0373ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105(1):185–199. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haq I, Murphy E, Dacre J. Osteoarthritis. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79:377–383. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.933.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das S, Farooqi A. Osteoarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(4):657–675. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Dieppe PA, et al. Osteoarthritis: new insights. Part 1: the disease and its risk factors. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(8):635–646. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-8-200010170-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bijlsma J, Berenbaum F, Lafeber F. Osteoarthritis: an update with relevance for clinical practice. Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2115–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heidari B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Caspian J Intern Med. 2011;2:205–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forss KS, Stjernberg L, Hansson EE. Osteoarthritis and fear of physical activity – the effect of patient education. Cogent Med. 2017;4(1):1328820. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown DW, Pleasants R, Ohar JA, et al. Health-related quality of life and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in North Carolina. N Am J Med Sci. 2010;2(2):60. doi: 10.4297/najms.2010.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Machado GP, Gignac MA, Badley EM. Participation restrictions among older adults with osteoarthritis: a mediated model of physical symptoms, activity limitations, and depression. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59(1):129–135. doi: 10.1002/art.23259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis MA, Ettinger WH, Neuhaus JM, Mallon KP. Knee osteoarthritis and physical functioning: evidence from the NHANES I Epidemiologic Followup Study. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(4):591–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Prisma Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reijnders JS, Ehrt U, Weber WE, Aarsland D, Leentjens AF. A systematic review of prevalence studies of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23(2):183–189. doi: 10.1002/mds.21803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnell K, Weiss CO, Lee T, et al. The prevalence of clinically-relevant comorbid conditions in patients with physician-diagnosed COPD: a cross-sectional study using data from NHANES 1999–2008. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westerik JA, Metting EI, van Boven JF, Tiersma W, Kocks JW, Schermer TR. Associations between chronic comorbidity and exacerbation risk in primary care patients with COPD. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0512-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rai KK, Jordan RE, Siebert WS, et al. Birmingham COPD Cohort: a cross-sectional analysis of the factors associated with the likelihood of being in paid employment among people with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:233. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S119467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee TA, Pickard AS, Bartle B, Weiss KB. Osteoarthritis: a comorbid marker for longer life? Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(5):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garin N, Koyanagi A, Chatterji S, et al. Global multimorbidity patterns: a cross-sectional, population-based, multi-country study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;71(2):205–214. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumbhare S, Pleasants R, Ohar JA, Strange C. Characteristics and prevalence of asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):803–810. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-554OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lalkhen H, Mash R. Multimorbidity in non-communicable diseases in South African primary healthcare. S Afr Med J. 2015;105(2):134–138. doi: 10.7196/samj.8696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park HJ, Leem AY, Lee SH, et al. Comorbidities in obstructive lung disease in Korea: data from the fourth and fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1571. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S85767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Putcha N, Han MK, Martinez CH, et al. the COPDGene® Investigators Comorbidities of COPD have a major impact on clinical outcomes, particularly in African Americans. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1(1):105. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.1.1.2014.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwab P, Dhamane AD, Hopson SD, et al. Impact of comorbid conditions in COPD patients on health care resource utilization and costs in a predominantly Medicare population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:735. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S112256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mapel DW, Hurley JS, Frost FJ, Petersen HV, Picchi MA, Coultas DB. Health care utilization in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a case-control study in a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(17):2653–2658. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wijnhoven HA, Kriegsman DM, Hesselink AE, De Haan M, Schellevis FG. The influence of co-morbidity on health-related quality of life in asthma and COPD patients. Respir Med. 2003;97(5):468–475. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2002.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yeo J, Karimova G, Bansal S. Co-morbidity in older patients with COPD – its impact on health service utilisation and quality of life, a community study. Age Ageing. 2006;35(1):33–37. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karch A, Vogelmeier C, Welte T, et al. COSYCONET Study The German COPD cohort COSYCONET: Aims, methods and descriptive analysis of the study population at baseline. Respir Med. 2016;114:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Järvholm B, Lewold S, Malchau H, Vingård E. Age, bodyweight, smoking habits and the risk of severe osteoarthritis in the hip and knee in men. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20(6):537–542. doi: 10.1007/s10654-005-4263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mnatzaganian G, Ryan P, Norman P, Davidson D, Hiller J. Smoking, body weight, physical exercise, and risk of lower limb total joint replacement in a population-based cohort of men. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(8):2523–2530. doi: 10.1002/art.30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandmark H, Hogstedt C, Lewold S, Vingard E. Osteoarthrosis of the knee in men and women in association with overweight, smoking, and hormone therapy. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58(3):151–155. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.3.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang K, Shin J, Lee J, et al. Association between direct and indirect smoking and osteoarthritis prevalence in Koreans: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010062. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radeos M, Cydulka R, Rowe B, Barr R, Clark S, Camargo C. Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among patients in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27(2):191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barr R, Herbstman J, Speizer F, Camargo C., Jr Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nurses. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:965–971. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Berthelot JM, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of osteoarthritis in British Columbia, Canada. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(2):386e93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turkiewicz A, Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Engstrom G, et al. Prevalence of knee pain and knee OA in southern Sweden and the proportion that seeks medical care. Rheumatology. 2014;54(5):827–835. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Felson D. The epidemiology of knee osteoarthritis: Results from the framingham osteoarthritis study. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1990;20(3):42–50. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(90)90046-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, et al. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(1):172–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schols AM, Buurman WA, Van den Brekel AS, Dentener MA, Wouters EF. Evidence for a relation between metabolic derangements and increased levels of inflammatory mediators in a subgroup of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1996;51(8):819–824. doi: 10.1136/thx.51.8.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim HC, Mofarrahi M, Hussain SN. Skeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3(4):637. doi: 10.2147/copd.s4480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Yelin EH, et al. COPD as a systemic disease: impact on physical functional limitations. Am J Med. 2008;121(9):789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crisafulli E, Costi S, Luppi F, et al. Role of comorbidities in a cohort of patients with COPD undergoing pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax. 2008;63(6):487–492. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.086371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crisafulli E, Gorgone P, Vagaggini B, et al. Efficacy of standard rehabilitation in COPD outpatients with comorbidities. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(5):1042–1048. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00203809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh JR, McKeough ZJ, Morris NR, et al. Metabolic disease and participant age are independent predictors of response to pulmonary rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2013;33(4):249–256. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31829501b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Franssen F, Rochester C. Comorbidities in patients with COPD and pulmonary rehabilitation: do they matter? Eur Respir Rev. 2014;23(131):131–141. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spruit M, Singh S, Garvey C, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rochester C, Vogiatzis I, Holland A, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1373–1386. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-1966ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McNamara RJ, McKeough ZJ, McKenzie DK, Alison JA. Water-based exercise in COPD with physical comorbidities: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(6):1284–1291. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00034312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Groutas W, Dou D, Alliston K. Neutrophil elastase inhibitors. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2011;21(3):339–354. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.551115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rahmati M, Mobasheri A, Mozafari M. Inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis: A critical review of the state-of-the-art, current prospects, and future challenges. Bone. 2016;85:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sokolove J, Lepus C. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: latest findings and interpretations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5(2):77–94. doi: 10.1177/1759720X12467868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Torres J, Cordoba-Lanus E, López-Aguilar C, et al. C-reactive protein levels and clinically important predictive outcomes in stable COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(5):902–907. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00109605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wright H, Moots R, Bucknall R, Edwards S. Neutrophil function in inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Rheumatology. 2010;49(9):1618–1631. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muley M, Reid A, Botz B, Bölcskei K, Helyes Z, McDougall J. Neutrophil elastase induces inflammation and pain in mouse knee joints via activation of proteinase-activated receptor-2. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;173(4):766–777. doi: 10.1111/bph.13237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]