Abstract

Does intuition favor prosociality, or does prosocial behavior require deliberative self-control? The Social Heuristics Hypothesis (SHH) stipulates that intuition favors typically advantageous behavior – but which behavior is typically advantageous depends on both the individual and the context. For example, non-zero-sum cooperation (e.g. in social dilemmas like the Prisoner's Dilemma) typically pays off because of the opportunity for reciprocity. Conversely, reciprocity does not promote zero-sum cash transfers (e.g. in the Dictator Game, DG). Instead, DG giving can be long-run advantageous because of reputation concerns: social norms often require such behavior of women but not men. Thus, the SHH predicts that intuition will favor social dilemma cooperation regardless of gender, but only favor DG giving among women. Here I present meta-analytic evidence in support of this prediction. In 31 studies examining social dilemma cooperation (N=13,447), I find that promoting intuition increases cooperation to a similar extent for both men and women. This stands in contrast to the results from 22 DG studies (analyzed in Rand et al., 2016) where intuition promotes giving among women but not men. Furthermore, I show using meta-regression that the interaction between gender and intuition is significantly larger in the DG compared to the cooperation games. Thus, I find clear evidence that the role of intuition and deliberation varies across both setting and individual as predicted by the SHH.

Keywords: cooperation, dual-process, social heuristics, altruism

Humans regularly help others, even when doing so is personally costly. Such prosocial behavior is central to the success of human societies. Therefore, explaining why people are willing to incur such costs is a central question in social psychology. In recent years, there has been considerable interest in understanding the underpinnings of prosociality from a dual-process perspective (for a review, see Zaki & Mitchell, 2013). Dual-process models conceptualize decisions as arising from the interaction of cognitive processes that are relatively automatic, intuitive, and effortless, and cognitive processes that are relatively controlled, deliberative, and effortful (Gilovich, Griffin, & Kahneman, 2002; Sloman, 1996).

The Social Heuristics Hypothesis (SHH, Rand et al., 2014) has been proposed as a theoretical framework for understanding prosociality from a dual-process perspective. The SHH proposes that (i) intuition favors behaviors which are typically long-run payoff-maximizing, while (ii) deliberation leads to the behavior which is payoff-maximizing in the current situation. Of particular interest is “pure” prosociality in one-shot anonymous interactions (or, more broadly, interactions where future consequences are insufficient to outweigh the costs of being prosocial). Here, it is always self-interested to act selfishly, and thus deliberation is predicted to favor selfishness in these settings. Generating predictions regarding intuition, on the other hand, requires understanding which behaviors are optimal in more typical scenarios that involve future consequences – consequences created by, for example, repeated interactions (Trivers, 1971), reputation effects (Nowak & Sigmund, 2005), or the threat of sanctions (Fehr & Gächter, 2002); for a review see Rand & Nowak, 2013.

Which behavior is predicted to be favored by intuition, therefore, may vary across situations and across individuals (based on which behavior is typically advantageous for a given individual in a given situation). Here, we consider the interaction between two forms of such variation. With respect to situational factors, we consider differences in typically advantageous behavior between situations that involve multi-lateral non-zero-sum cooperation (i.e. social dilemmas such as the Prisoner's Dilemma) versus unilateral zero-sum transfers (i.e. giving in the Dictator Game, sometimes referred to as behavioral “altruism”). With respect to individual differences, we consider differences in typically advantageous behavior between men and women.

Because social dilemma cooperation involves non-zero-sum interactions, it can be payoff-maximizing to cooperate because of the chance for repeated interactions: If my cooperating with you today makes you more likely to cooperate with me tomorrow, reciprocity can lead long-run self-interest to favor cooperation (Fudenberg & Maskin, 1986). As a result, the SHH predicts that intuition should typically favor cooperation. This prediction is demonstrated formally by a mathematical model showing that, when repeated interactions are sufficiently common, strategies which intuitively cooperate and then use deliberation to switch to defection when in 1-shot anonymous settings are favored by evolution, learning, and strategic reasoning (Bear, Kagan, & Rand, 2017; Bear & Rand, 2016). The power of reciprocity to incentivize cooperation is a basic feature of social interaction, and thus its force does not vary based on gender. As a result, the SHH predicts that gender will not moderate the relationship between intuition and cooperation.

The situation is different, however, for Dictator Game giving. Because this form of giving is zero-sum, repetition does not create an incentive to give – giving money to someone and having them give it back to you makes you no better off than if you had just kept all the money in the first place. Thus, the only way that altruistic giving can be long-run payoff-maximizing is insomuch as giving is perceived positively (and/or not giving is perceived negatively) by others, and thereby influences their actions towards the altruistic giver in future non-zero-sum interactions.

Critically, a large literature on gender norms indicates that women are expected to be (and disproportionately occupy roles that mandate being) communal and unselfish (i.e. altruistic), whereas men are expected to be (and often occupy roles that benefit from being) agentic and independent (Eagly, 1987; Heilman & Okimoto, 2007). Thus, women experience reputational benefits from unilateral giving (and sanctions for not giving) much more so than men, such that unilateral giving may typically be long-run payoff maximizing – and thus favored by intuition – for women but not men. As a result, in contrast to social dilemma cooperation, the SHH leads to the prediction that gender is likely to be a moderator of the relationship between intuition and DG giving (see Supplementary Materials Section 1 for further discussion of gender and social dilemma cooperation).

Consistent with this prediction regarding DG giving, Study 1 from Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro, and Barcelo (2016) (hereafter RBECB) presented a meta-analysis of 22 experiments which showed that promoting intuition led to more DG giving relative to promoting deliberation among women, but had no significant effect among men. Furthermore, Study 2 showed that this relationship was moderated by self-identification with sex roles, such that women consistently gave more than men when intuition was promoted, but when deliberation was promoted, women who more strongly identified with traditionally masculine attributes (e.g. dominance, independence) reduced their giving (i.e. gave amounts similar to what was given by men).

However, the SHH prediction regarding a lack of interaction between gender and intuition in social dilemma cooperation has yet to be tested. Here, I evaluate this prediction using meta-analysis of 1-shot incentivized economic game experiments involving social dilemma cooperation in which the use of intuition versus deliberation was experimentally manipulated. I then compare the moderating role of gender in these cooperation decisions versus giving decisions in the DG using meta-regression.

Method

I take advantage of a dataset collected for a recent meta-analysis of cognitive processing and cooperation (Rand, 2016) which did not explore gender. This dataset included 51 studies involving social dilemma cooperation (referred to as “pure” cooperation in Rand, 2016): 1-shot anonymous games in which it is always payoff-maximizing to not cooperate, but where it could be payoff-maximizing to cooperate if the game had been repeated. Specifically, this included decisions in the 1-shot Prisoner's Dilemma, Public Goods Game, and Trust Game player two (“trustee” – cooperating can be payoff-maximizing for player one in the Trust Game, and so is not included). In these experiments, cognitive processing mode was manipulated via time constraints (intuition increased by applying time pressure, deliberation increased by applying time delay), cognitive load (intuition increased by having participants complete a cognitively demanding task while playing the game), ego depletion (intuition increased by having participants complete a cognitively demanding task prior to playing the game), and intuition inductions (intuition increased by writing about a time in one's life when intuition worked well/careful reasoning worked poorly or being directly instructed to use intuition, deliberation increased by writing about a time in one's life when intuition worked poorly/deliberation worked well or being directly instructed to deliberate). Importantly, there were no indications of publication bias in this dataset, using either small-study effect tests (Egger's or Begg's test) or using the p-curve test for “p-hacking” (Simonsohn, Nelson, & Simmons, 2014), and there is no danger of publication bias regarding the gender-related questions considered in the current paper, since none of the original papers from which the data came analyzed gender or the interaction between gender and cognitive processing. For further details about the construction of the underlying dataset, see Rand, 2016.

I had access to raw data with gender information for 31 of the social dilemma studies from Rand, 2016, with combined N=13,447 (these 31 studies contained 84.8% of the total N in Rand, 2016; see Supplementary Materials Table S1 for study list and details). I take percentage of the endowment spent on cooperating as my measure of cooperation. I code gender as 0=male, 1=female, and code cognitive processing manipulations as 0=more deliberative condition, 1=more intuitive condition. All main effects, interactions, and simple effects are calculated using linear regressions taking cooperation as the dependent variable and the appropriate combination of these gender and cognitive processing variables as independent variables. As in Rand, 2016, my main analyses exclude participants who were non-compliant with the cognitive processes manipulations (i.e. did not answer quickly enough in the time pressure condition, answered too quickly in the time delay condition, or did not write long enough responses in the recall induction), but I also include secondary analyses including all participants (an intent-to-treat analysis) to ensure that any results observed are not driven by selection effects (for extended discussion of selection effects and non-compliance, see Bouwmeester et al., 2017 and Rand, 2017).

All analyses consider the overall effect across all studies using random effects meta-analysis implemented using the metan function in Stata/SE 14.2, which uses the standard DerSimonian & Laird method to estimate between studies variance. See Supplementary Materials Section 2 for analysis of heterogeneity in effect size across studies.

Results

Random effects meta-analysis finds a significant main effect of cognitive processing manipulation, such that participants in the more intuitive condition spent 8.2 percentage points (95% CI [4.9, 11.4], Z=4.97, p<.0001) more of their endowment on cooperation than participants in the more deliberative condition (including non-compliance participants, effect size 5.9 percentage points, 95% CI [2.9, 9.0], Z=3.83, p=.0001); and a significant main effect of gender, such that women spent 3.7 percentage points (95% CI [2.2, 5.2], Z=4.88, p<.0001) more than men (including non-compliance participants, effect size 3.5 percentage points, 95% CI [2.1, 4.8], Z=4.93, p<.0001).

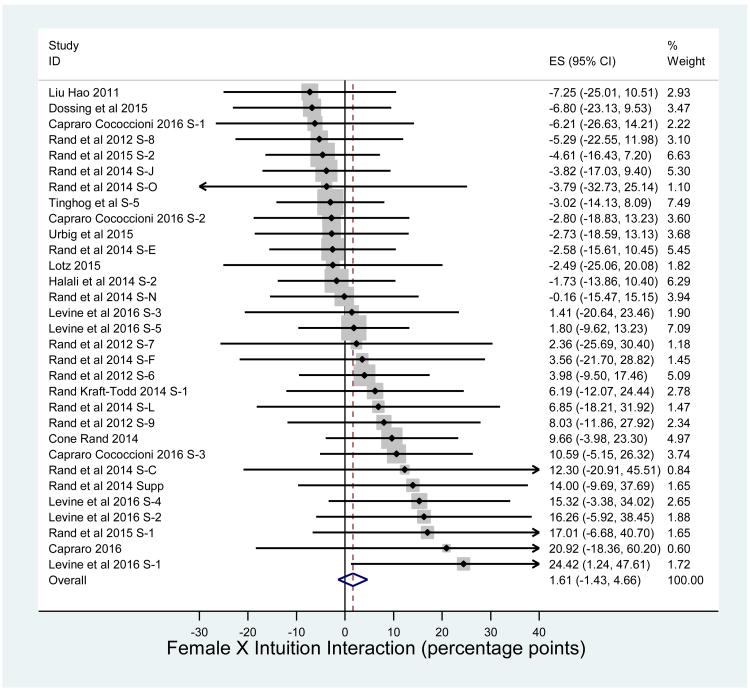

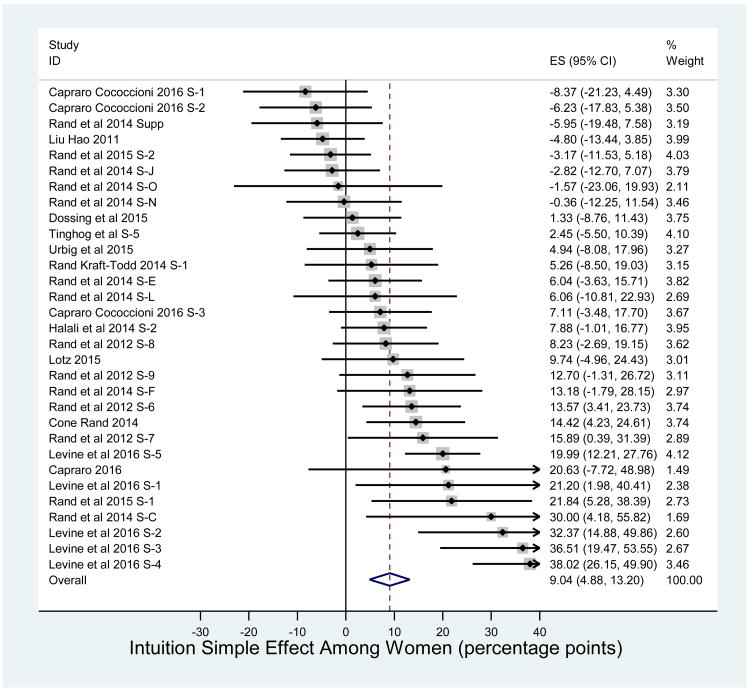

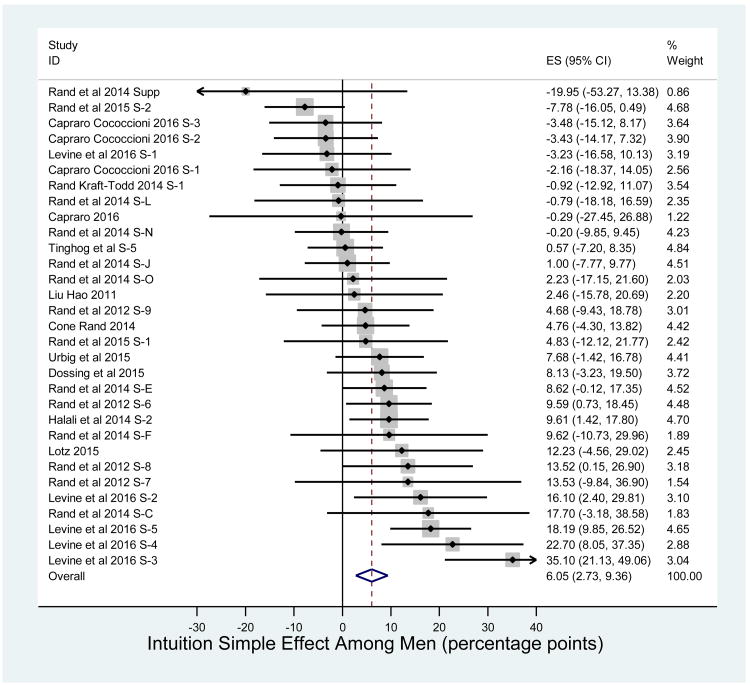

Critically, as predicted, random effects meta-analysis did not find a significant interaction between gender and promoting intuition, interaction effect size 1.6 percentage points, 95% CI [-1.4, 4.7], Z=1.04, p=.29 (Figure 1) (including non-compliant participants, interaction effect size 1.1 percentage points, 95% CI [-1.6, 3.9], Z=.80, p=.43). Instead, there is a roughly equally sized positive effect of intuition on cooperation among women, effect size 9.0 percentage points, 95% CI [4.9, 13.2], Z=4.26, p<.0001 (Figure 2) (including non-compliant participants, effect size 7.1 percentage points, 95% CI [3.3, 10.8], Z=3.69, p<.0001); and among men, effect size 6.2 percentage points, 95% CI [2.7, 9.4], Z=3.57, p<.0001 (Figure 3) (including non-compliant participants, effect size 5.0 percentage points, 95% CI [2.2, 7.8], Z=3.45, p=.001). Thus, in contrast to the results observed for DG giving in RBECB, I find that intuition promotes social dilemma cooperation among men and women to a similar extent. (Although strategic cooperation is not the focus of the current paper, there is also no interaction between gender and intuition in strategic cooperation games; see Supplemental Materials Section 3.)

Figure 1.

Effect size (i.e. raw regression coefficient) for interaction between gender (0=male, 1=female) and cognitive processing mode (0=more deliberative, 1=more intuitive) for each social dilemma cooperation experiment. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Gray squares indicate weight placed on each study by random effects meta-analysis.

Figure 2.

Effect size on social dilemma cooperation of promoting intuition among women for each experiment. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Gray squares indicate weight placed on each study by random effects meta-analysis.

Figure 3.

Effect size on social dilemma cooperation of promoting intuition among men for each experiment. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Gray squares indicate weight placed on each study by random effects meta-analysis.

To show that this difference in gender interaction effect sizes is itself significant, I use random effects meta-regression on the combined dataset of the 31 social dilemma cooperation studies analyzed here and the 22 DG studies analyzed in RBECB.

In order to compare prosociality levels across the different types of games, I follow the normalization procedure of Peysakhovich, Nowak, and Rand (2014), whereby giving 50% of the endowment in the DG is “as cooperative” as contributing 100% of the endowment in the cooperation games (i.e. I multiply DG giving values by 2). The logic behind this renormalization is that the normative (and socially optimal) action in the DG is to give half – thus giving half in the DG corresponds to being maximally prosocial, like contributing everything in a Public Goods Game. However, my results are not contingent on this normalization – see Supplementary Materials Section 4 for details.

Furthermore, I use cooperation game interaction effect sizes including non-compliant participants (i.e. using the more conservative intent-to-treat analysis), because non-compliant participants were included in the effect sizes calculated in RBECB (although all meta-regression results reach equivalent levels of significance if non-compliant participants are excluded from the cooperation data).

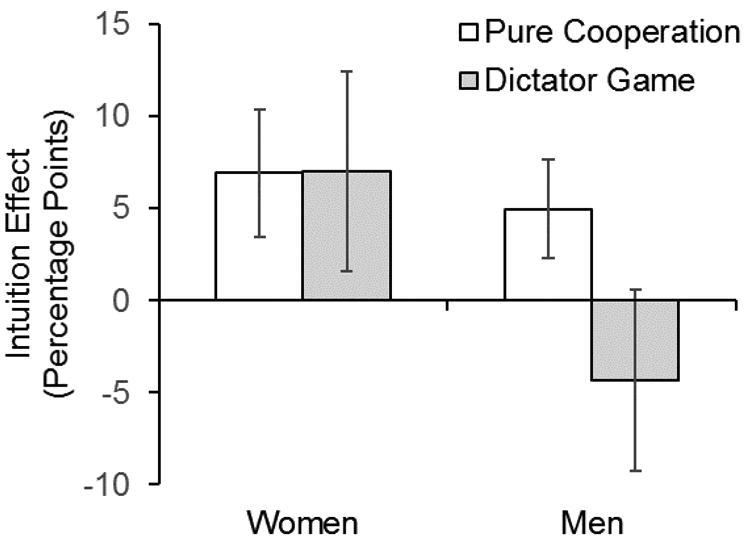

Random effects meta-regression shows that the gender-intuition interaction effect size was significantly larger in the DG studies compared to the cooperation studies (9.9 percentage points larger, t=2.99, p=.004). Decomposing the interaction by gender (Figure 4), I find that, among men, the intuition effect was significantly smaller in the DG compared to the cooperation games (9.3 percentage points smaller, t=-3.26, p=.002); among women, conversely, there was no significant difference in intuition effect size between the DG and the cooperation games (.1 percentage points difference, t=.02, p=.99).

Figure 4.

Effect size of promoting intuition on social dilemma cooperation versus DG giving for men versus women. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Furthermore, these results are all robust to excluding the 20 studies that used time constraints (10.4 percentage point larger gender-intuition interaction effect in the DG, t=2.60, p=.014; among men, 12.8 percentage point smaller intuition effect in the DG, t=-3.12, p.004; among women, 1.8 percentage point smaller intuition effect in the DG, t=-.39, p=.70). This is important because a much larger fraction of the cooperation studies used time constraints compared to the DG studies, and RBECB found some suggestive (although non-significant) evidence that there was less of a gender interaction among time constraint studies.

Discussion

Here I have presented meta-analytic evidence that intuition favors prosociality for women regardless of whether there is a potential for mutual benefit, whereas intuition only favors prosociality for men in the context of social dilemma cooperation (where such a mutual benefit is possible) and not DG giving (which is zero-sum). Taken together, these findings validate the moderation predictions of the SHH. My results also fit nicely with the observation that there are consistent gender differences in DG giving but not cooperation (Croson & Gneezy, 2009), and help to elucidate the cognitive basis for this difference in where gender differences appear.

The lack of interaction between gender and intuition for social dilemma cooperation reported here is at odds with the results of Espinosa & Kovářík, 2015, who analyzed a small subset of the data I consider here (2 of the 31 studies included in my analysis) and did find gender moderation. The fact that no such moderation effect emerges from the much larger dataset used here suggests that their earlier finding was spurious, and highlights the importance of meta-analysis and large multi-lab datasets, particularly when examining interaction effects.

Finally, the results reported here suggest that, despite within-individual correlations between altruism and cooperation (Capraro, Jordan, & Rand, 2014; Peysakhovich et al., 2014; Yamagishi et al., 2013) and the ability of habituating to cooperation vs defection to influence subsequent altruism (Peysakhovich & Rand, 2016; Stagnaro, Arechar, & Rand, 2016), there are fundamental differences in the cognition and daily-life forces that shape altruism versus cooperation. Further empirical exploration of, and theoretical development regarding, these differences is an important direction for future work on prosociality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge funding from the Templeton World Charity Foundation (grant no. TWCF0209), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency NGS2 program (grant no. D17AC00005), and the National Institutions of Health (grant no. P30-AG034420), useful discussion from Jesse Graham, and copyediting by SJ Language Services.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bear A, Kagan A, Rand DG. Co-Evolution of Cooperation and Cognition: The Impact of Imperfect Deliberation and Context-Sensitive Intuition. Proc Roy Soc B. 2017;284(1851) doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear A, Rand DG. Intuition, deliberation, and the evolution of cooperation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016;113(4):936–941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517780113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester S, Verkoeijen PP, Aczel B, Barbosa F, Bègue L, Brañas-Garza P, et al. Espín AM. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Registered Replication Report: Rand, Greene, and Nowak (2012): 2017. 1745691617693624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capraro V. Unpublished data 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Capraro V, Cococcioni G. Rethinking spontaneous giving: Extreme time pressure and ego-depletion favor self-regarding reactions. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27219. doi: 10.1038/srep27219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capraro V, Jordan JJ, Rand DG. Heuristics guide the implementation of social preferences in one-shot Prisoner's Dilemma experiments. Scientific Reports. 2014;4:6790. doi: 10.1038/srep06790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone J, Rand DG. Time Pressure Increases Cooperation in Competitively Framed Social Dilemmas. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e115756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croson R, Gneezy U. Gender Differences in Preferences. Journal of economic literature. 2009;47(2):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Døssing F, Piovesan M, Wengstrom E. Cognitive Load and Cooperation. Review of Behavioral Economics. 2017;4(1):69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-role Interpretation. Mahwah, New Jersey: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa MP, Kovářík J. Prosocial behavior and gender. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2015;9:88. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Gächter S. Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature. 2002;415(6868):137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudenberg D, Maskin ES. The Folk Theorem in Repeated Games with Discounting or with Incomplete Information. Econometrica. 1986;54(3):533–554. [Google Scholar]

- Gilovich T, Griffin D, Kahneman D. Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment. Cambridge University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Halali E, Bereby-Meyer Y, Meiran N. Between Self-Interest and Reciprocity: The Social Bright Side of Self-Control Failure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014;143(2):745–754. doi: 10.1037/a0033824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilman ME, Okimoto TG. Why are women penalized for success at male tasks?: The implied communality deficit. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92(1):81–92. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine E, Barasch A, Rand D, Berman J, Small D. Unpublished data 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Liu CJ, Hao F. An application of a dual-process approach to decision making in social dilemmas. American Journal of Psychology. 2011;124(2):203–212. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.124.2.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz S. Spontaneous Giving Under Structural Inequality: Intuition Promotes Cooperation in Asymmetric Social Dilemmas. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0131562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA, Sigmund K. Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature. 2005;437(7063):1291–1298. doi: 10.1038/nature04131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peysakhovich A, Nowak MA, Rand DG. Humans Display a ‘Cooperative Phenotype’ that is Domain General and Temporally Stable. Nature Communications. 2014;5:4939. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peysakhovich A, Rand DG. Habits of Virtue: Creating Norms of Cooperation and Defection in the Laboratory. Management Science. 2016;62(3):631–647. [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG. Cooperation, fast and slow: Meta-analytic evidence for a theory of social heuristics and self-interested deliberation. Psychological Science. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0956797616654455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG. Reflections on the Time-Pressure Cooperation Registered Replication Report. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1745691617693625. 1745691617693625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG, Brescoll VL, Everett JAC, Capraro V, Barcelo H. Social heuristics and social roles: Intuition favors altruism for women but not for men. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2016;145(4):389–396. doi: 10.1037/xge0000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG, Greene JD, Nowak MA. Spontaneous giving and calculated greed. Nature. 2012;489(7416):427–430. doi: 10.1038/nature11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG, Kraft-Todd GT. Reflection Does Not Undermine Self-Interested Prosociality. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;8:300. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG, Newman GE, Wurzbacher O. Social context and the dynamics of cooperative choice. Journal of Behavioral decision making. 2015;28(2):159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG, Nowak MA. Human Cooperation. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2013;17(8):413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand DG, Peysakhovich A, Kraft-Todd GT, Newman GE, Wurzbacher O, Nowak MA, Green JD. Social Heuristics Shape Intuitive Cooperation. Nature Communications. 2014;5:3677. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsohn U, Nelson LD, Simmons JP. P-curve: A key to the file-drawer. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2014;143(2):534–547. doi: 10.1037/a0033242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloman SA. The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychological bulletin. 1996;119(1):3. [Google Scholar]

- Stagnaro MN, Arechar AA, Rand DG. From Good Institutions to Good Norms: Top-Down Incentives to Cooperate Foster Prosociality But Not Norm Enforcement. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.01.017. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2720585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tinghög G, Andersson D, Bonn C, Böttiger H, Josephson C, Lundgren G, et al. Johannesson M. Intuition and cooperation reconsidered. Nature. 2013;497(7452):E1–E2. doi: 10.1038/nature12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivers R. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1971;46(1):35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Urbig D, Terjesen S, Procher V, Muehlfeld K, van Witteloostuijn A. Come on and take a free ride: Contributing to public goods in native and foreign language settings. Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2015 doi: 10.5465/amle.2014.0338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi T, Mifune N, Li Y, Shinada M, Hashimoto H, Horita Y, et al. Simunovic D. Is behavioral pro-sociality game-specific? Pro-social preference and expectations of pro-sociality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2013;120(2):260–271. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki J, Mitchell JP. Intuitive Prosociality. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(6):466–470. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.