Abstract

Tobacco use is the most common cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States; it accounts for one-third of all cancer deaths and is thought to account for half of preventable cancer deaths. We describe the Tobacco Treatment Program at a major academic cancer center. Patients and employees may access these services in a number of ways. All current smokers and recent quitters are proactively contacted and invited to participate. The services provided are tailored to the motivational level of individual patients and their immediate medical needs. The treatment pathways we present are based on our experience from the last 10 years in treating over 5,000 unique patients with around 60,000 patient visits. These pathways include behavioral counseling and pharmacotherapy, including first-line, second-line, and off-label medication use. We provide a description of our program with the goal of providing guidance and ideas to others who are developing treatment programs and providing treatment to tobacco users.

Keywords: Tobacco cessation, lung cancer, cancer prevention

Introduction

Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States.1 The nicotine in tobacco is highly addictive, and nicotine dependence is a serious impediment to tobacco cessation. There is now wide consensus on the efficacy of evidence-based tobacco cessation behavioral strategies and pharmacological treatments, expanded implementation of which would significantly decrease smoking rates and the development of tobacco-related diseases.2

It is estimated that about one-third of patients who smoked prior to their illness continue to smoke after receiving their cancer diagnosis.3 Tobacco use among cancer patients can have an adverse effect on their overall survival and quality of life.4 In addition, smoking during treatment leads to the increased incidence of serious adverse effects such as oral mucositis, pulmonary and cardiovascular complications, weight loss, impaired wound healing, and infection.5,6 Continuing to smoke has been reported to decrease the effectiveness of cancer treatment. For example, response rates by the end of radiation therapy have been reported to be lower in smokers than in nonsmokers or smokers who quit prior to treatment.7 Smoking may also reduce the efficacy of chemotherapy. An example is the finding that smoking induces the hepatic metabolism of chemotherapy drugs, thereby reducing their therapeutic effects.8 Continued smoking also increases the rate of surgical complications, an important consideration because surgery is a major treatment for cancer. The numerous effects of smoking on surgical outcomes, including increased re-intubation, aspiration/respiratory infections, increased length of stay, and wound dehiscence, are so detrimental that surgeons now often will not operate unless a smoker has been abstinent for several weeks.9

Conversely, stopping smoking prior to cancer diagnosis or treatment can improve survival outcomes.10 Among smokers in general, higher self-efficacy and increased perception of harm are positively related to success in quitting smoking.11 Several studies have shown that patients' desire and motivation to quit tobacco increases after a cancer diagnosis, particularly if their cancer is known to be causally related to tobacco use (e.g. lung, bladder, and head and neck cancers).12,13 Thus, a cancer diagnosis presents an opportunity for health care providers to offer a tobacco cessation intervention. The United States Public Health Service 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline (PHS 2008) on treating tobacco use and dependence found robust evidence that evidence-based counseling and pharmacotherapy independently improved abstinence rates in smokers and together doubled the abstinence rates of either modality alone. Results were so compelling that the use of medications and counseling together is considered standard of care for all smokers and tobacco users.2 The recommended counseling usually consists of motivational enhancement, problem solving, skills training, and social support, while the pharmacotherapy options for smoking cessation include five nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs: nicotine gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, and patch) and the non-nicotine medications bupropion sustained release [SR] (Zyban®) or extended release [XL] and varenicline (Chantix®).2

Cancer patients have unique challenges for smoking cessation: they often struggle with high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression;14 they are often older with multiple failed quit attempts; they may have complex medication regimens; and they may be experiencing side effects of illness and treatment. Many of these (in particular, stress, anxiety, and depression) are associated with smoking and smoking relapse and may respond to some treatments better than others.6 Cancer patients and their partners tend to experience cancer-related distress15 that can overwhelm their sense of coherence. As Stark et al.16 noted, cancer treatment, while holding promise of remission of the disease, often results in unmanageable anxiety that may complicate or hinder tobacco cessation. Therefore, it is recommended that comprehensive treatment of cancer include a robust treatment program for tobacco use along with identification and treatment of psychiatric symptoms and disorders.17

Although many cancer centers offer some form of tobacco cessation support, only a few cancer centers currently provide a full spectrum of tobacco cessation services to all of their patients.18,19 In order to provide high-quality individualized care for a population with comorbidities and numerous relapse challenges, it is important to implement a programmatic structure that allows for a wide range of motivational (readiness to quit) states, nicotine dependence, economic challenges, psychiatric challenges, and scheduling challenges. Here, we describe and present diagrams illustrating treatment tracks, or treatment pathways, in the Tobacco Treatment Program (TTP) at MD Anderson Cancer Center that we have developed and refined over the past 10 years. We also present basic outcome data on abstinence rates that our patients have achieved.

Methods

The TTP was developed in 2006 by faculty in the Department of Behavioral Science and other departments within the institution. The TTP is funded through annual proceeds from the State of Texas 1998 tobacco settlement funds20 and offers tobacco-cessation services, including behavioral counseling and tobacco-cessation pharmacologic treatments, at no cost to all our patients and employees who are current tobacco users or have quit within the past 12 months (recent quitters). The treatment strategies used within the program were developed to meet (and in some cases exceed) the standards established by the Public Health Service of the United States Department of Health and Human Services (the PHS 2000 and, later, updated 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence).21,2 Importantly, the TTP has also served as a natural laboratory for developing clinical innovations, many of which have now been incorporated into our program.

TTP Entry Points

At its outset, the program relied on provider referrals, but we now use an aggressive approach to recruitment. For all cancer patients, smoking/tobacco use status is recorded in the electronic health record by providers during any clinical or preclinical evaluation. Our staff pull this information into our database daily, where patients are identified as “current tobacco users” if they have any regular use of tobacco products and as “recent quitters” if they have quit within the last 12 months. Current tobacco users and recent quitters are then called proactively by program staff in 4 call attempts. The purpose of the call is to assess the most appropriate level of intervention based on their current circumstances, motivation (readiness to quit and interest in treatment), and level of cancer treatment intensity.22 While the program continues to highly encourage providers to discuss tobacco status with their patients and make referrals, it no longer relies on provider referrals as the only entry point. In addition, patients and employees may self-refer.

TTP Treatment Pathways

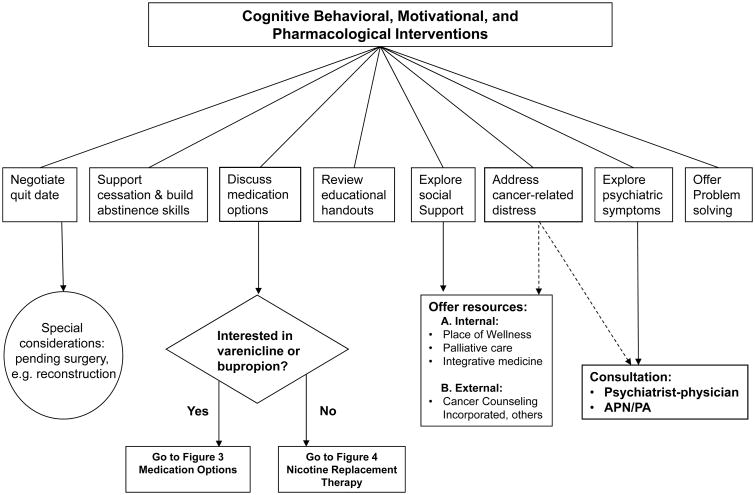

At the onset of the program, TTP clinical staff and addiction psychiatrist developed a series of treatment pathways to help guide treatment choices such that the unique needs of our cancer patients could be met. Those pathways were modified annually to incorporate the most recently published literature and clinical staff feedback based on our treatment experiences, with the aim of providing the most effective treatment. The pathways channel patients into three alternative treatment options; Figure 1 summarizes those options.

Figure 1. Tobacco Treatment Program.

Patients who are not reached by phone as well as those who are reached but are not ready to quit tobacco use are sent self-help materials. Patients who are interested in quitting tobacco use and opt to do telephone-only counseling are sent educational materials and are scheduled for a call with a licensed therapist. In addition to the phone-only counseling option, these patients can opt to get over-the-counter pharmacological treatments or prescription medications through their physicians. In contrast, patients who are able and interested in attending an in-person visit receive a full evaluation, as described below and as shown in Figure 2. The active management and evaluation of first-line prescription medications and nicotine replacement strategies are detailed in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Medications are used as monotherapies or in combination.

Figure 2. Outpatient & Inpatient Counseling.

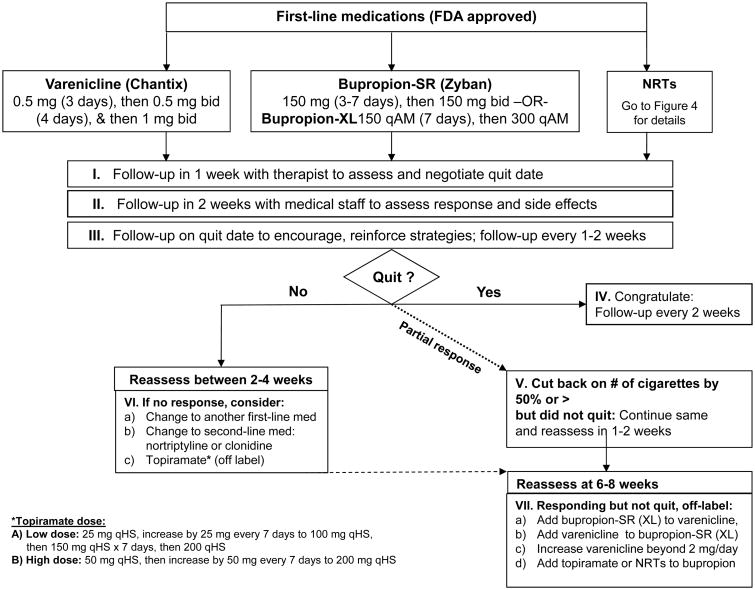

Figure 3. Medication Options.

Figure 4. Nicotine Replacement Therapies (NRTs).

TTP Assessment

As part of the initial clinical evaluation, all newly registered patients are scheduled for a 90- to 120-minute appointment. At this initial appointment, our support staff obtain vital signs, weight, and carbon monoxide (CO) level in expired breath (measured using a CO breathalyzer). The CO level serves as a biologic marker for cigarette consumption. The patient then completes a battery of computerized assessments, followed by meetings with a therapist and with a prescribing clinician.

The computerized questionnaire takes 30 minutes on average to complete; it has built-in skip patterns to minimize repetitive items between questionnaires, where applicable. It contains the following standardized screens:

smoking/tobacco use in the last 30 days with timeline follow-back method (TLFB)23

nicotine dependence based on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)24

alcohol use disorders using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)25

depressive symptomatology screen based on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)26

negative affect symptoms on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)27

nicotine withdrawal symptoms on the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale (WSWS),28 which evaluates affective and other symptoms of nicotine withdrawal, including anger, concentration, hunger, anxiety, sleep, and sadness

psychiatric disorders using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ),29 which assesses disorders and symptoms of depression, anxiety, panic attacks, insomnia, and alcohol use.

After completing the assessment battery, tobacco users have a roughly 45-minute face-to-face interview with a therapist. TTP therapists are trained in motivational interviewing, have mental health counseling experience, and are at a master's or PhD level. The therapist records medical and psychiatric history, current medical/cancer treatments, psychosocial history, substance use history, tobacco use history, and prior attempts at quitting tobacco use. Subsequently, the therapist communicates a summary of the relevant information to the medical clinician, who then meets with the patient to determine and prescribe the most appropriate cessation medication. TTP medical clinicians constitute an addiction psychiatrist, physician assistant, or advanced practice nurse, in addition to a registered nurse.

TTP Cognitive Behavioral and Motivational Interventions

Individual and group counseling, whether in person or by telephone, have both been shown to be efficient and effective in helping tobacco users achieve and maintain abstinence; in addition, counseling efficacy increases with treatment duration and intensity.2 TTP patients who are interested in the phone-only option receive an initial phone session with a therapist that can last up to 45 minutes, followed by 3-4 phone follow-up sessions of 15-30 minutes. Phone-only patients can convert anytime to the more intensive program. The level of counseling (duration and intensity) depends on factors such as the patient's level of nicotine dependence, pending or scheduled cancer treatments (surgeries, chemotherapy, or radiation), comorbid psychiatric disorders, and available social support.

During the follow-up counseling sessions, whether in person or by phone, TTP therapists work with patients to negotiate a quit date, as shown in Figure 2, or reconcile barriers to quitting through a motivational approach. Special considerations are made for cancer patients who need an emergent cancer treatment for which continued smoking would have immediate adverse effects (e.g. reconstructive surgery or stem cell transplantation). These patients may need to quit tobacco as soon as possible and sometimes have to be abstinent up to 4-6 weeks before receiving a reconstructive surgical intervention. Therapists assist patients in building and maintaining abstinence skills and help them develop problem-solving and coping skills that can be utilized before and after quitting. Patients are also evaluated and treated for baseline psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Patients who present with or develop symptoms and disorders associated with nicotine withdrawal, such as depression, anxiety, anger, craving, excessive hunger, difficulties with concentration, sadness, and sleep disturbance, that may pose barriers to cessation are referred to the program's addiction psychiatrist for further evaluation and treatment.

Patients who are unable to set a quit date or who struggle to maintain abstinence are engaged in motivational approaches to address ambivalence and barriers to quitting. Therapists also assist patients in exploring alternative behavior change options, such as a trial quit attempt or setting tobacco scheduled reduction goals, which may ultimately lead to patients being able to set a quit date (Figure 2).

TTP Pharmacotherapy

Pharmacotherapy has been shown to significantly increase abstinence, with a doubling of abstinence rates across large trials, when combined with minimal counseling.30 Several studies and meta-analyses have confirmed the efficacy of bupropion, varenicline, and NRTs alone or in combination for tobacco cessation in the general population.31 The TTP utilizes these medications as first-line therapies, as detailed in Figures 3 and 4. The PHS 2008 guideline2 includes evidence for the efficacy of clonidine and nortriptyline, which are not FDA approved for tobacco cessation, but can be used as second-line agents for treating tobacco abuse and are used as such at the TTP. Topiramate is also used (off label) at the TTP for treatment of smoking cessation as it has been shown to have efficacy compared to placebo.32 The PHS 2008 guideline lists five first-line NRTs that effectively increase long-term abstinence: a gum, an oral inhaler, a lozenge, a nasal spray, and a patch. The nicotine patch delivers a steady amount of nicotine and is used in the TTP as one of the first-line NRTs for cigarette smokers (Figure 4-A). The amount of time that patients receive any particular dose level can be increased or reduced on an individual basis.

The TTP also treats patients who use tobacco products other than cigarettes, including cigars, pipes, smokeless tobacco, and more recently, e-cigarettes. By default, patients initially receive the higher dose of FDA-approved NRTs. However, if a patient prefers, bupropion or varenicline can be used; several papers have reported that these are efficacious for smokeless tobacco.33-35

Prior to the consultation visit, each cancer patient's medical record is reviewed by a medical professional (nurse, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner) in order to gather information or contraindications that may affect tobacco cessation medication choices (either bupropion, varenicline, or NRTs; Figure 3). At week 2 following initiation of pharmacotherapy, patients receive a phone call for a brief follow-up by a nurse, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner to assess for treatment response and side effects (Figure 3). At any time point, those who develop side effects or who have not responded (i.e., have not quit or reduced their tobacco use by 50% or more) can be switched to a different first-line or a second-line medication (clonidine or nortriptyline).

Patients who are yet to achieve abstinence are re-evaluated between weeks 2 and 4. If they have reduced their tobacco use by 50% or more (have shown a partial response) to pharmacotherapy, their pharmacological regimen may be augmented with a second NRT. The TTP favors and uses by default nicotine gum and lozenges rather than other NRTs as add-ons to the patch, owing to their relatively low cost and ease of use (Figure 4-A & B). Patients who show a partial response are reassessed at weeks 6-8. If they have not quit using tobacco at that point but remain motivated to do so, their treatment may be augmented by additional medications (e.g. addition of bupropion to varenicline or vice versa, addition of topiramate or NRTs to bupropion, or increase in varenicline dosage above 2 mg/day; Figure 3).

During this initial 10-week period, patients receive smoking cessation medications free of charge as part of the program. In the subsequent 3-month period, patients are provided another 3-month prescription to fill on their own (as maintenance medication, if they were on bupropion or varenicline and did quit). All patients receive follow-up assessments of their smoking status every 3 months through 1 year from the end of the active treatment phase. These assessments are completed by phone and are typically initiated by non-clinical support staff.

Results

From the program's inception in January 2006 through the end of May 2016, we have served over 5,000 unique patients and conducted over 60,000 clinic visits. We analyzed a cohort of patient data between January 2006 and August 2013, consisting of 4,111 new patients, attending approximately 35,000 follow-up appointments, from more than 50 clinical departments. The outcome data analysis, completed in 2013, was based on 2,779 individuals (out of 4111) who had reached the 9-month follow-up time point from the completion of an initial consultation visit. We found that more than 40% of patients enrolled in the TTP presented at baseline with at least one or more current mental health disorder as assessed by the PHQ, including anxiety, depression, panic disorder, or alcohol abuse. Our overall follow-up rates are based on the number of patients in the respondent-only group divided by the number of patients who had initiated treatment. Those follow-up rates are relatively high at each time point: at 3 months, 89% (2,479/2,779); at 6 months, 82% (2,282/2,779); and at 9 months, 75% (2,085/2,779). Among patients who responded to the 9-month call, the self-reported smoking abstinence rate was about 47%. These outcomes are not based on intent-to-treat, owing to the removal of treatment non-initiators and interview non-completers from the denominator. Using the assumption that all of those who did not respond to the 9-month call had relapsed, the abstinence rate for treatment initiators was about 38%. Although counting non-responders as relapsers is a very conservative assumption, this abstinence rate compares favorably to program-based observational studies using similar assessment methods and is higher than reported outcomes for individuals with cancer who smoke.36 In addition to those patients who reported being abstinent from tobacco use, those who did not quit reported a reduction in average cigarettes per day from a mean of 11 cigarettes per day (SD + 10.6) to a mean of 5 (SD + 8.0) cigarettes per day at the end of active treatment, which occurred around 10 weeks from the first consultation date.

About 10% of our patients come in for in-person follow-up visits, allowing us to measure CO in exhaled breath as a biologic marker of abstinence. In a recent data analysis among those who had come to one or more follow-ups in person we found 90% concordance between CO measure and self-reported abstinence rates (unpublished data 2016), which strengthens the validity of the self-reporting of abstinence among our patients.

Discussion

The treatment pathways that we have developed and refined over the past 10 years, illustrated in Figures 1 through 4, are a comprehensive approach of providing counseling, pharmacotherapy, and regular follow-up to support tobacco cessation in cancer patients. Our patients' abstinence and smoking reduction outcomes are comparatively high and support these unique paradigms for treatment. It is important to note that a cancer diagnosis can be a “teachable moment” that propels a patient to quit immediately, seek help to quit, or maintain abstinence. Several studies have shown that patients' desire and motivation to quit tobacco increases after a cancer diagnosis, particularly if their cancer is known to be causally related to tobacco use (e.g. lung cancer, bladder, and head and neck cancer).12,13 Thus, a cancer diagnosis presents an opportunity for health care providers to help by offering a tobacco cessation intervention.

There are numerous tobacco cessation strategies and medications available to help the average tobacco user quit. However, it is important to note that many of our patients are facing possible life-threatening diagnoses and often experience high levels of distress. We have found that established treatment pathways can help guide tobacco cessation treatment plans, especially in the care of this more complex and treatment-resistant population of smokers (i.e. cancer patients). Within these pathways, attention to patients' particular challenges and circumstances allow development of individualized treatment plans. TTP leadership and staff have iteratively developed those treatment pathways for ergonomic and evidence-based treatment of patients with multiple comorbidities and relapse challenges at our center; these pathways can be used by other cancer centers as a template for developing their own tobacco treatment programs.

Our results and recommendations are limited in being observational, based on a naturalistic cohort analysis at a single institution; on the other hand, they are based on a vast experience in treating over 5,000 unique patients thus far. We would underscore that these pathways are not empirically tested or based on controlled randomized trials; they are better thought of as an example of experiential implementation of evidence-based treatment, demonstrating a compelling effect in a challenging population. Our goal for those pathways is to serve as an example of how a mature program might approach treatment of tobacco dependence within a cancer center. A strength of this program is the provision of free services predicated on the existence of settlement funds (since many smokers are from a low socioeconomic status or have no health insurance). Once the settlement monies end, it will be a challenge to identify other funding streams to provide the robust services that are not covered under insurance coverage for tobacco cessation, which can vary by insurer and over time. Therefore, a major limitation of this paper is the generalizability of this structure to programs that do not have access to large funding sources and cannot provide free services. However, several elements of the program, such as brief counseling and basic medication prescribing can be delivered within the currently available insurance coverage for tobacco cessation treatment thus can be adapted across institutional settings.

Reference List

- 1.van Meijgaard J, Fielding JE. Estimating benefits of past, current, and future reductions in smoking rates using a comprehensive model with competing causes of death. [Accessed September 26, 2016];Prev Chronic Dis. 9:E122. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110295. PM:22765931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update, Clinical Practice Guideline Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsons A, Daley A, Begh R, Aveyard P. Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balduyck B, Sardari NP, Cogen A, et al. The effect of smoking cessation on quality of life after lung cancer surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(6):1432–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen AM, Chen LM, Vaughan A, et al. Tobacco smoking during radiation therapy for head-and-neck cancer is associated with unfavorable outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(2):414–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gritz ER, Fingeret MC, Vidrine DJ, Lazev AB, Mehta NV, Reece GP. Successes and failures of the teachable moment: Smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106(1):17–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Browman GP, Wong G, Hodson I, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:159–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301213280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dresler CM, Gritz ER. Smoking, smoking cessation and the oncologist. Lung Cancer. 2001;34(3):315–23. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00333-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gronkjaer M, Eliasen M, Skov-Ettrup LS, et al. Preoperative smoking status and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2014;259(1):52–71. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182911913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking--50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schnoll RA, James C, Malstrom B. Longitudinal predictors of continued tobacco use among patients diagnosed with cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25/30:214–21. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2503_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gritz ER, Nisenbaum R, Elashoff R, Holmes EC. Smoking behavior following diagnosis in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Causes and Control. 1991;2:105–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00053129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gritz ER, Carr CR, Rapkin D, et al. Predictors of long-term smoking cessation in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 1993;2:261–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valentine AD. Depression, anxiety, and delirium. In: Pazdur R, Coia L, Hoskins WJ, Wagman L, editors. Cancer management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 10th. The Oncology Group; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 855–99. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gustavsson-Lillius M, Julkunen J, Keskivaara P, Hietanen P. Sense of coherence and distress in cancer patients and their partners. Psychooncology. 2007;16:1100–10. doi: 10.1002/pon.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark D, House A. Anxiety in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1261–7. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karam-Hage M, Cinciripini PM, Gritz ER. Tobacco use and cessation for cancer survivors: an overview for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):272–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.21231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meert A, Mayer C, Milani M, Beckers J, Razavi D. Smoking cessation interventions among cancer patients. Bulletin du Cancer. 2006;4:363–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan G, Schnoll RA, Alfano CM, et al. National Cancer Institute Conference on Treating Tobacco Dependence at Cancer Centers. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3):178–82. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobacco Prevention and Control Program. Texas Tobacco Settlement Information. DSHS Mental Health and Substance Abuse Division. [Accessed August, 2016];2011 http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/tobacco/settlement.shtm.

- 21.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical practice guideline. Respiratory Care. 2000;53(9):1217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabius V, Karam-Hage M, Blalock JA, Cinciripini PM. Meaningful use “provides a meaningful opportunity”. Cancer. 2013;20:464–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente GM. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsch SK, Smith SS, Wetter DW, Jorenby DE, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Development and validation of the Wisconsin Smoking Withdrawal Scale. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7(4):354–61. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stead LF, Lancaser T. Does a combination of smoking cessation medication and behavioural support help smokers to stop? [Accessed August, 2016];Cochrane Reviews. 2012 Dec 12; http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD008286/does-a-combination-of-smoking-cessation-medication-and-behavioural-support-help-smokers-to-stop.

- 31.Mills EJ, Wu P, Lockhart I, Thorlund K, Puhan M, Ebbert JO. Comparisons of high-dose and combination nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, and bupropion for smoking cessation: a systematic review and multiple treatment meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2012;44(6):588–97. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2012.705016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oncken C, Arias AJ, Feinn R, et al. Topiramate for smoking cessation: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(3):288–96. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain R, Jhanjee S, Jain V, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial of varenicline for smokeless tobacco dependence in India. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(1):50–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebbert JO, Fagerstrom K. Pharmacological interventions for the treatment of smokeless tobacco use. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(1):1–10. doi: 10.2165/11598450-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aggarwal A, Jain M, Jiloha RC. Varenicline for smokeless tobacco dependence. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56(1):50. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.62414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzales DH, Rennard SI, Billing CB, Reeves K, Watsky E, Gong J. A pooled analysis of varenicline, an alpha 4 beta 2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist vs bupropion, and placebo for smoking cessation. SRNT. 2006:45–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]