Abstract

Background

Cancer survivors are more likely to be unemployed than individuals without a cancer history, however employment participation after early-stage breast cancer has not been widely studied. The objectives of this study were to evaluate employment trajectories in a cohort of early-stage breast cancer patients and age-matched controls from diagnosis to 2-year follow-up, and identify factors associated with diminished and emerging employment participation.

Methods

As part of a larger cohort study of 1,096 early-stage breast cancer patients and same-aged women without breast cancer, data from 723 working-age (40-64 years) women (347 patients and 376 controls) were analyzed to evaluate four employment trajectories (sustained unemployment, diminished employment, emerging employment, sustained employment). Multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify factors associated with diminished employment versus sustained employment, and emerging employment versus sustained unemployment.

Results

Lower proportions of patients (71%) than controls (79%) reported full- or part-time employment at enrollment (p < 0.01). Fatigue was a significant predictor of diminished employment for both patients (OR=5.71, 95% CI =2.48-13.15) and controls (OR=2.38, 95% CI=1.21-5.28). Among patients, African-American race (OR=4.02, 95% CI=1.57-10.28) and public/uninsured insurance status (OR=4.76, 95% CI =1.34-12.38) were associated with diminished employment. Among controls, high social support was associated with emerging employment (OR=3.12, 95% CI =1.25-7.79).

Conclusions

Fatigued patients, African-American patients and publicly insured/uninsured cancer patients were more likely to experience diminished employment after two years of follow-up. Further investigation with longer follow-up is warranted to identify factors associated with these disparities in employment participation after early-stage breast cancer treatment.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Survivorship, Employment, Fatigue, Return to Work

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among women in the United States, excluding skin cancer.1 Advances in detection and treatment over the last few decades have led to increases in survival rates and life expectancy.1 More than 3 million women in the United States are living with breast cancer, and by 2024, the number of women with breast cancer is expected to rise to 4 million.2 As the population of breast cancer survivors continues to increase, it is increasingly important to address the unique needs of this growing population, including long-term health care and the return to normalcy.

Compared with other female cancers, breast cancer is more frequently diagnosed among women of working age (<65 years).1 As a result, the impact of breast cancer on employment outcomes has the potential to be substantial. During treatment, work schedule changes to accommodate provider visits and the reduced physical or mental ability to perform occupational tasks may result in a premature exit from the workforce. Furthermore, the presence of lingering side effects after surgical or adjuvant therapy may influence employment outcomes long after treatment ends.3, 4 Although cancer survivors are more likely to report unemployment than individuals without a cancer history,5-10 working after diagnosis may represent a return to normalcy for some breast cancer patients. In addition to the added benefit of employer-sponsored health insurance, paid employment has the potential to mitigate the financial stresses associated with cancer.11, 12 Moreover, for women with breast cancer, employment could play a significant role in post-diagnostic health. Health benefits associated with employment include an increased sense of purpose, higher self-esteem, and a stronger sense of social support from others, all of which have been associated with improved quality of life.13, 14

A limited number of longitudinal studies have examined employment outcomes among women diagnosed with breast cancer.15-17 Sociodemographic factors such as older age, lower education, and lower income,18, 19 treatment-related factors such as axillary lymph node dissection, chemotherapy and mastectomy,20 and psychosocial factors such as poor self-rated health and social support have been associated with poorer employment outcomes.21, 22 The purpose of this study was to: (a) evaluate two-year employment participation trajectories at 2-year follow-up in a cohort of patients after diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer and an age-matched control group without a breast cancer history, and (b) identify sociodemographic, psychosocial, and clinical factors associated with diminished and emerging employment in this cohort.

Methods

Participants

We examined data from a longitudinal prospective cohort study of women diagnosed with incident stage 0-IIA breast cancer and women without any breast cancer history (controls). The purpose of the parent study was to examine changes in quality of life over time in women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer and age-matched controls.23 Descriptions of the study population have been published elsewhere.23-26 Briefly, between 2003 and 2007, women ages 40 and older were recruited from two sites in St. Louis, Missouri, USA: Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital/Washington University School of Medicine and from Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Women with a diagnosis of first primary breast cancer were eligible for the study, and controls were identified within two weeks of a normal/benign screening mammogram and were frequency-matched by age group to patients. Women ages 40 and older were included in the study because, screening mammography was recommended for women in this age group during the study period.27 Exclusion criteria included a prior history of in situ or invasive breast cancer, receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, inability to speak and understand English, or evidence of cognitive impairment on the Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test (administered to participants 65 years of age or older).28 Computer-assisted telephone interviews were administered to study participants at four times: 4–6 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years following definitive surgical treatment (patients) or screening mammogram (controls). The study was reviewed and approved by the institution review boards at both institutions, and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

A total of 1,096 women (549 patients and 547 controls) enrolled in the study, including 826 participants who were of working age (<65 years) at the time of enrollment.23 For this exploratory, secondary data analysis of employment participation trajectories, we excluded women who reported being retired (n = 96) at enrollment. We also limited our analysis to White and African-American women because of small proportion of participants from other racial/ethnic groups (n = 7). The current study therefore includes a total of 723 study participants (347 patients and 376 controls).

Employment outcomes

We evaluated employment trajectories at 2-year follow-up. At each interview, study participants were asked whether they were currently “Employed Full-time”, “Employed Part-time”, “Unemployed/Unable to work,” “Homemaker,” or “Retired.” Participants who reported full- or part-time work were classified at Employed. We created four categories to classify the employment trajectories of study participants: 1) sustained employment (Employed at each time point); 2) diminished employment (Employed at Time1 but not at any of the other time points); 3) emerging employment (Unemployed/Unable to work/Homemaker at Time1 and Employed at Time4); and 4) sustained unemployment (Unemployed/Unable to work/Homemaker at each time point). The primary outcome measures of this study were diminished employment and emerging employment at 2-year follow-up.

Sociodemographic, psychosocial and patient characteristics

Interviews included questions about participants’ age, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education level, and insurance status. Comorbidity was determined based on the Charlson comorbidity index.29, 30 At each interview, quality of life was measured using the eight subscales of the RAND 36-Item Health Survey.31-33 We used the vitality subscale of the RAND-36 to measure participants’ fatigue. The vitality subscale is comprised of four items asking how patients felt “during the past 4 weeks.” Standardized scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater vitality (i.e., lower scores reflecting more fatigue). We used two questions to determine depression history at enrollment: “Has a doctor ever told you that you had depression?” and “Have you ever been treated for depression with medication or psychotherapy?” An affirmative response to either question indicated a history of depression. The 19-item Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey was used to assess social support, with higher scores (range from “none of the time” [1] to “all the time” [5]) indicating more social support.34 All patients underwent surgery (lumpectomy or mastectomy), and medical record review confirmed patients’ receipt of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or endocrine therapy (which is prescribed for patients with estrogen-receptor positive tumors) during follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the distribution of sociodemographic, psychosocial and patient characteristics by diagnostic group (patients versus controls). We performed chi-square analyses and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine differences between diagnostic groups by sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics. Chi-square tests and ANOVAs were also conducted to examine sociodemographic, psychosocial and patient (receipt of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy) characteristics in association with the trajectory of employment.

We used two multivariable logistic regression models to estimate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for characteristics associated with employment trajectory at the 2-year follow-up. In the first model, we evaluated the associations between participant characteristics and diminished employment (versus sustained employment). In the second model, we evaluated the associations between participant characteristics and emerging employment (versus sustained unemployment). Potential model covariates, based on the literature17, 35-39, included age (continuous), race (African-American or White), marital status (married/partnered or not married/partnered), socioeconomic status (income less than $50,000 and high school graduate education or less, income less than $50,000 and greater than high school education, or income greater than or equal to $50,000), insurance type (public/uninsured/unknown or private), number of comorbidities (two or more, one, or none), social support (continuous), vitality (median split of RAND36 vitality subscale), depression history (yes or no), and treatment during study (patients only: surgery only, surgery and chemotherapy, surgery and radiation, surgery and chemotherapy and radiation), and endocrine therapy during study (patients only: yes or no). Adjusted odds ratios were estimated separately for patient and control groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

The study sample included a total of 347 patients and 376 controls. Descriptive characteristics of the sample by diagnosis group are reported in Table 1. The average age at baseline for both diagnostic groups was 52 years (median age = 52 years; range 40-64 years). Lower proportions of patients than controls had private insurance and reported full- or part-time employment at enrollment. A significant difference in socioeconomic status was observed between the groups with a greater proportion of controls reporting annual household income at or above $50,000 than controls. A higher proportion of patients scored below the median of the RAND36 vitality subscale than controls, and the mean social support score for patients was significantly higher than the score for controls. We found no significant differences in any of the other baseline characteristics between the patient and control groups (Table 1). Only five patients experienced recurrence of their breast cancer during follow-up.

Table1.

Characteristics of the study population at enrollment by diagnostic group (n = 723)

| Patients (n = 347) |

Controls (n = 376) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P valuea | |

| Age (years) | 52.3 | 6.2 | 51.6 | 6.1 | 0.12 |

| Social Support | 4.4 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 0.8 | <0.01 |

|

| |||||

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | P valuea | |

|

| |||||

| Race | 0.06 | ||||

| African-American | 68 | (19.6) | 96 | (25.5) | |

| White | 279 | (80.4) | 280 | (74.5) | |

| Marital status | 0.56 | ||||

| Married/partnered | 218 | (62.8) | 244 | (64.9) | |

| Not married/partnered | 129 | (37.2) | 132 | (35.1) | |

| Socioeconomic status | <0.01 | ||||

| <$50,000 income, ≤HS graduate | 58 | (16.7) | 55 | (14.6) | |

| <$50,000 income, >HS graduate | 98 | (28.2) | 71 | (18.9) | |

| ≥$50,000 income | 191 | (55.0) | 250 | (66.5) | |

| Insurance status | 0.05 | ||||

| Public/uninsured/unknown | 71 | (20.5) | 56 | (14.9) | |

| Private | 276 | (79.5) | 320 | (85.1) | |

| Employment status | <0.01 | ||||

| Employed | 245 | (70.6) | 297 | (79.0) | |

| Not Employed | 102 | (29.4) | 79 | (21.0) | |

| Comorbidity | 0.86 | ||||

| 2+ | 36 | (10.4) | 36 | (9.6) | |

| 1 | 61 | (17.6) | 71 | (18.9) | |

| 0 | 250 | (72.1) | 269 | (71.5) | |

| Vitality score | <0.001 | ||||

| Below median | 193 | (55.6) | 101 | (26.9) | |

| At or above median | 154 | (44.1) | 275 | (73.1) | |

| History of depression | 0.90 | ||||

| Yes | 147 | (42.4) | 161 | (42.8) | |

| No | 200 | (57.6) | 215 | (57.2) | |

| Treatment during study | N/A | ||||

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiation | 74 | (21.3) | |||

| Surgery + radiation | 146 | (42.1) | |||

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 39 | (11.2) | |||

| Surgery only | 88 | (25.4) | |||

| Endocrine therapy during study | N/A | ||||

| Yes | 216 | (62.2) | |||

| No | 131 | (37.8) | |||

p-values derived from one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Bold type indicates statistical significance.

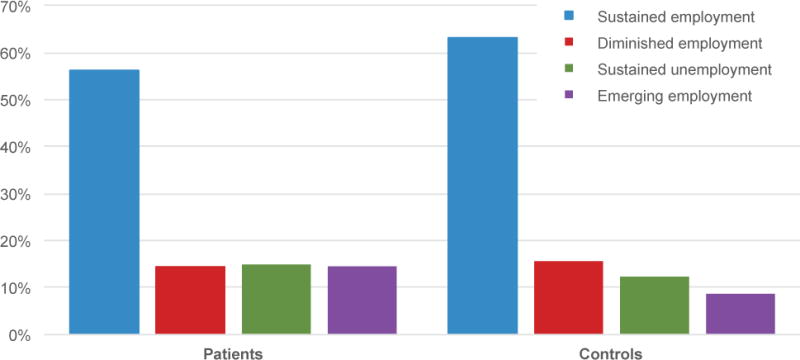

Table 2 and Figure 1 show the characteristics of employment participation trajectories of the study sample by diagnostic group. The proportion of women with sustained employment participation after two years was 56% in the patient group and 63% in the control groups. There were no significant differences in employment trajectories between the two diagnostic groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Employment trajectories of the study population by diagnostic group (n = 723)

| Patients (n = 347) |

Controls (n = 376) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | P valuea | |

| Employment trajectory | 0.05 | ||||

| Sustained employment | 195 | (56.2) | 238 | (63.3) | |

| Diminished employment | 50 | (14.4) | 59 | (15.7) | |

| Sustained unemployment | 52 | (15.0) | 46 | (12.2) | |

| Emerging employment | 50 | (14.4) | 33 | (8.8) | |

Chi-square p-value

Figure 1.

Employment trajectories by diagnostic group

Univariate characteristics of women who were employed at enrollment are presented in Table 3. Of the 245 patients who were employed at enrollment, 50 (20%) experienced diminished employment during follow-up. Among patients, diminished employment participation was more likely to occur for women were African-American, had public/uninsured/unknown insurance status, and a reported vitality score below the median. A total of 59 (out of 297, 20%) controls experienced diminished employment. Similar to patients, African-American race and a vitality score below the median were associated with diminished employment. Different from the patient group, low socioeconomic status was also associated with diminished employment among controls.

Table 3.

Univariate characteristics by employment trajectory among women employed at enrollment (n = 542)

| Patients | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Sustained Employment (n = 195) |

Diminished Employment (n = 50) |

Sustained Employment (n = 238) |

Diminished Employment (n = 59) |

|||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P valuea | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P valuea | |

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | 52.0 (6.1) | 53.3 (5.9) | 0.16 | 51.6 (6.1) | 51.4 (6.2) | 0.82 |

| Social support score | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.7) | 0.42 | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.8) | 0.86 |

|

| ||||||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | P valuea | No. (%) | No. (%) | P valuea | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | <0.001 | <0.01 | ||||

| White | 176 (90.3) | 35 (70.0) | 199 (83.6) | 38 (64.4) | ||

| African-American | 19 (9.7) | 15 (30.0) | 39 (16.4) | 21 (35.6) | ||

| Marital status | 0.05 | 0.36 | ||||

| Married/partnered | 134 (68.7) | 27 (54.0) | 168 (70.6) | 38 (64.4) | ||

| Not married/partnered | 61 (31.3) | 23 (46.0) | 70 (29.4) | 21 (35.6) | ||

| Live alone | 0.79 | 0.74 | ||||

| Yes | 32 (16.4) | 9 (18.0) | 40 (16.8) | 11 (18.6) | ||

| No | 163 (83.6) | 41 (82.0) | 198 (83.2) | 48 (81.4) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | 0.23 | 0.01 | ||||

| <$50,000 income, ≤HS graduate | 20 (10.3) | 9 (18.0) | 15 (6.3) | 9 (15.3) | ||

| <$50,000 income, >HS graduate | 43 (22.0) | 13 (26.0) | 38 (16.0) | 15 (25.4) | ||

| ≥$50,000 income | 132 (67.7) | 28 (56.0) | 185 (77.7) | 35 (59.3) | ||

| Insurance | <0.01 | 0.10 | ||||

| Public/uninsured/unknown | 12 (6.2) | 11 (22.0) | 13 (5.5) | 7 (11.9) | ||

| Private | 183 (93.8) | 39 (78.0) | 225 (94.5) | 52 (88.1) | ||

| Comorbidity | 0.88 | 0.26 | ||||

| 2+ | 16 (8.2) | 4 (8.0) | 12 (5.0) | 6 (10.2) | ||

| 1 | 33 (16.9) | 10 (20.0) | 39 (16.4) | 12 (20.3) | ||

| 0 | 146 (74.9) | 36 (72.0) | 187 (78.6) | 41 (69.5) | ||

| Vitality score | <0.001 | <0.01 | ||||

| Below median | 89 (45.6) | 38 (76.0) | 45 (18.9) | 21 (35.6) | ||

| At or above median | 106 (54.4) | 14 (24.0) | 193 (81.1) | 38 (64.4) | ||

| History of depression | 0.40 | 0.35 | ||||

| Yes | 73 (37.4) | 22 (44.0) | 89 (37.4) | 26 (44.1) | ||

| No | 122 (62.6) | 28 (56.0) | 149 (62.6) | 33 (55.9) | ||

| Treatment during study | 0.73 | |||||

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiation | 44 (22.6) | 13 (26.0) | ||||

| Surgery + radiation | 89 (45.6) | 20 (40.0) | ||||

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 12 (6.2) | 5 (10.0) | ||||

| Surgery only | 50 (25.6) | 12 (24.0) | ||||

| Endocrine therapy during study | 0.28 | |||||

| Yes | 133 (68.2) | 30 (60.0) | ||||

| No | 62 (31.8) | 20 (40.0) | ||||

p-values derived from one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Bold type indicates statistical significance.

In Table 4, we summarize the univariate characteristics of women who were not employed at enrollment. Approximately 49% of patients (50/102) and 41% of controls (33/79) experienced new employment during follow-up. Surgical patients who were treated with both chemotherapy and radiation and surgical patients treated with only chemotherapy were more likely to experience new employment than patients treated with surgery alone. Patients treated with endocrine therapy were less likely to experience new employment. Among controls, higher socioeconomic status, private insurance status, the absence of comorbidities, age, and social support were associated with new employment.

Table 4.

Univariate characteristics by employment trajectory among women not employed at enrollment (n = 181)

| Patients | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Sustained Unemployment (n = 52) |

Emerging Employment (n = 50) |

Sustained Unemployment (n = 46) |

Emerging Employment (n = 33) |

|||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P value* | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P value* | |

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | 53.3 (7.0) | 51.8 (6.2) | 0.24 | 53.3 (6.1) | 50.0 (5.1) | <0.01 |

| Social support score | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.8) | 0.61 | 3.8 (1.0) | 4.4 (0.7) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| No. (%) | No. (%) | P valuea | No. (%) | No. (%) | P valuea | |

|

| ||||||

| Race | 0.58 | 0.35 | ||||

| White | 36 (69.2) | 32 (64.0) | 23 (50.0) | 20 (60.6) | ||

| African-American | 16 (30.8) | 18 (36.0) | 23 (50.0) | 13 (39.4) | ||

| Marital status | 0.98 | 0.61 | ||||

| Married/partnered | 29 (55.8) | 28 (56.0) | 21 (45.6) | 17 (51.5) | ||

| Not married/partnered | 23 (44.2) | 22 (44.0) | 25 (54.4) | 16 (48.5) | ||

| Live alone | 0.92 | 0.24 | ||||

| Yes | 10 (19.2) | 10 (20.0) | 12 (26.1) | 5 (15.2) | ||

| No | 42 (80.8) | 40 (80.0) | 34 (73.9) | 28 (84.8) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | 0.36 | 0.02 | ||||

| <$50,000 income, ≤HS graduate | 18 (34.6) | 11 (22.0) | 24 (52.2) | 7 (21.2) | ||

| <$50,000 income, >HS graduate | 20 (38.5) | 22 (44.0) | 9 (19.6) | 9 (27.3) | ||

| ≥$50,000 income | 14 (26.9) | 17 (34.0) | 13 (28.3) | 17 (51.5) | ||

| Insurance | 0.85 | 0.02 | ||||

| Public/uninsured/unknown | 24 (46.2) | 24 (48.0) | 26 (56.5) | 10 (30.3) | ||

| Private | 28 (53.8) | 26 (52.0) | 20 (43.5) | 23 (69.7) | ||

| Comorbidity | 0.40 | 0.05 | ||||

| 2+ | 10 (19.2) | 6 (12.0) | 14 (30.4) | 4 (12.1) | ||

| 1 | 10 (19.2) | 8 (16.0) | 13 (28.3) | 7 (21.2) | ||

| 0 | 32 (61.6) | 36 (72.0) | 19 (41.3) | 22 (66.7) | ||

| Vitality score | 0.57 | 0.23 | ||||

| Below median | 35 (67.3) | 31 (62.0) | 23 (50.0) | 12 (36.4) | ||

| At or above median | 17 (32.7) | 19 (38.0) | 23 (50.0) | 21 (63.6) | ||

| History of depression | 0.32 | 0.31 | ||||

| Yes | 29 (55.8) | 23 (46.0) | 29 (63.0) | 17 (51.5) | ||

| No | 23 (44.2) | 27 (54.0) | 17 (37.0) | 16 (48.5) | ||

| Treatment during study | 0.01 | |||||

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiation | 6 (11.5) | 11 (22.0) | ||||

| Surgery + radiation | 26 (50.0) | 11 (22.0) | ||||

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 7 (13.5) | 15 (30.0) | ||||

| Surgery only | 13 (25.0) | 13 (26.0) | ||||

| Endocrine therapy during study | 0.05 | |||||

| Yes | 32 (61.5) | 21 (42.0) | ||||

| No | 20 (38.5) | 29 (58.0) | ||||

p-values derived from one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Bold type indicates statistical significance.

Diminished Employment Participation

Table 5 presents adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for diminished employment at 2-year follow-up. African-American race and public or uninsured insurance status were significantly associated with diminished employment participation among patients, after adjusting for age, marital status, socioeconomic status, vitality score, comorbidity, social support, treatment type, and endocrine therapy during study (Table 5). In both patients and controls, we observed a significant increase in risk for diminished employment among women who scored below the median on the vitality subscale. Only one of the five patients with recurrence reported diminished employment.

Table 5.

Logistic regression for the relationship between selected characteristics and diminished employment

| Patients ORa (95% CI) |

Controls ORb (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Continuous | 1.02 (0.97, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) |

| Race | ||

| African-American | 4.02 (1.57, 10.28) | 2.40 (1.00, 5.03) |

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/partnered | 0.98 (0.40, 2.40) | 1.07 (0.51, 2.24) |

| Not married/partnered | Reference | Reference |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||

| <$50,000 income, ≤HS graduate | 1.43 (0.46, 4.42) | 2.22 (0.76, 6.48) |

| <$50,000 income, >HS graduate | 0.77 (0.28, 2.08) | 1.75 (0.61, 4.99) |

| ≥$50,000 income | Reference | Reference |

| Insurance status | ||

| Public/uninsured/unknown | 4.76 (1.34, 12.38) | 1.75 (0.61, 4.99) |

| Private | Reference | Reference |

| Vitality Score | ||

| Below median | 5.71 (2.48, 13.15) | 2.38 (1.21, 4.68) |

| At or above median | Reference | Reference |

| Comorbidity | ||

| 2+ | 0.75 (0.22, 2.59) | 1.56 (0.50, 4.86) |

| 1 | 0.96 (0.39, 2.40) | 0.84 (0.37, 1.93) |

| None | Reference | Reference |

| Social support | ||

| Continuous | 1.00 (0.55, 1.82) | 1.24 (0.81, 1.90) |

| Treatment during study | ||

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiation | 1.62 (0.58, 4.51) | |

| Surgery + radiation | 0.99 (0.41, 2.42) | |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 1.47 (0.36, 6.05) | |

| Surgery only | Reference | |

| Endocrine therapy during study | ||

| Yes | 0.62 (0.29, 1.33) | |

| No | Reference |

Adjusted for age, race, marital status, socioeconomic status, insurance status, vitality score, comorbidity, social support, treatment type, and endocrine therapy during study. Bold type indicates statistical significance.

Adjusted for age, race, marital status, socioeconomic status, insurance status, vitality score, comorbidity, and social support. Bold type indicates statistical significance.

Emerging Employment Participation

We observed a greater likelihood for emerging employment participation in controls who reported higher levels of social support. We did not observe any significant associations with emerging employment among patients (Table 6), and four of the patients with recurrence reported sustained unemployment at follow-up.

Table 6.

Logistic regression for the relationship between selected characteristics and emerging employment

| Patients ORa (95% CI) |

Controls ORb (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Continuous | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) | 0.91 (0.82, 1.01) |

| Race | ||

| African-American | 1.00 (0.30, 3.35) | 4.75 (0.59, 38.59) |

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/partnered | 1.04 (0.31, 3.50) | 0.11 (0.01, 1.05) |

| Not married/partnered | Reference | Reference |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||

| <$50,000 income, ≤HS graduate | 0.39 (0.08, 1.86) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.65) |

| <$50,000 income, >HS graduate | 0.61 (0.16, 2.40) | 0.37 (0.04, 3.54) |

| ≥$50,000 income | Reference | Reference |

| Insurance status | ||

| Public/uninsured/unknown | 1.51 (0.50, 4.59) | 0.24 (0.05, 1.15) |

| Private | Reference | Reference |

| Vitality Score | ||

| Below median | 0.74 (0.26, 2.06) | 1.53 (0.44, 5.32) |

| At or above median | Reference | Reference |

| Comorbidity | ||

| 2 | 0.77 (0.20, 3.00) | 0.29 (0.05, 1.79) |

| 1 | 0.79 (0.21, 2.91) | 0.38 (0.09, 1.55) |

| 0 | Reference | Reference |

| Social support | ||

| Continuous | 1.01 (0.55, 1.86) | 3.12 (1.25, 7.79) |

| Treatment during study | ||

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiation | 1.74 (0.46, 6.63) | |

| Surgery + radiation | 0.56 (0.17, 1.86) | |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 2.36 (0.67, 8.27) | |

| Surgery only | Reference | |

| Endocrine therapy during study | ||

| Yes | 0.53 (0.21, 1.38) | |

| No | Reference |

Adjusted for age, race, marital status, socioeconomic status, insurance status, vitality score, comorbidity, social support, treatment type, and endocrine therapy during study

Adjusted for age, race, marital status, socioeconomic status, insurance status, vitality score, comorbidity, and social support

Discussion

In this study of early-stage breast cancer patients and age-matched controls, we observed that African-American patients were four times more likely to experience diminished employment participation during the two years after definitive surgical treatment than white patients. We also observed that insurance status was associated with diminished employment as patients with public, uninsured, or unknown status were 4.7 times more likely to experience diminished employment participation than patients with private insurance. In both patients and controls, fatigue was associated with diminished employment; although the association among controls was of lower magnitude than that of patients.

Our study focused on early-stage breast cancer patients, a population that has an excellent prognosis for disease-free survival.40 Although our sample included patients with stages 0-II breast cancer, only five patients experienced a recurrence over the 2-year follow-up, and we did not find any significant associations between employment participation outcomes and adjuvant therapies like chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormonal therapy. Fatigue, however, was a significant predictor of diminished employment participation in both patient and control groups. Cancer-related fatigue is among the most common and debilitating symptoms in breast cancer patients. With significant impacts that can last long after treatment, our results support prior findings that fatigue can be a barrier to both continued employment and return to work after cancer.22, 36, 41-45

Our findings that African-American race was independently associated with diminished employment participation are consistent with two prior U.S. longitudinal investigations of the relationship between race/ethnicity and employment after breast cancer. In these studies that included employed, insured women with newly diagnosed breast cancer, African-American patients were less likely than white patients to return to work at nine months14, and at 18 months after chemotherapy, radiation, or surgical treatment.35 In our study, neither surgery alone nor surgery combined with adjuvant therapies was associated with employment participation outcomes in our multivariable analyses. Nonetheless, our findings that sociodemographic factors (race and insurance status), but not type of treatment received, were associated with diminished employment participation contrast with some, but not all, studies that have evaluated associations between treatment and employment outcomes among breast cancer survivors.17, 36, 38, 46-53

A strength of our study is that we examined employment patterns among women who were unemployed at time of enrollment. With regard to emerging employment participation in patients, we did not observe any significant associations with any sociodemographic, psychosocial or clinical factors. In contrast, among controls, we observed a greater likelihood for emerging employment participation among women who reported higher levels of social support. The physical burden of cancer may affect patients’ employment seeking behaviors. Furthermore, social support, while necessary, may not be sufficient to overcome functional limitations in patients who would like to work, whereas controls may not have these same functional limitations, and those controls with support may be better enabled to seek employment over time. However, given the relatively small sample sizes of the sustained unemployment referent groups (patient group n = 22; control group n = 18), associations should be interpreted with caution. Still, previous research has indicated a role for psychosocial factors in long-term employment outcomes after cancer.44, 54, 55

Additional study strengths include its longitudinal design and inclusion of a control group of age-matched women. Our use of a control group allowed us to account for contextual factors, such as social and economic conditions, that may have had an influence on employment participation during the study period. Our study also has several limitations. First, this study was an exploratory, secondary analysis of existing data, and we were underpowered to detect differences between groups in adjusted models (e.g., patients with emerging employment versus sustained unemployment). Also, there were differences in the baseline characteristics between patients and controls, including differences in employment status and fatigue at enrollment; there also may be differences in unmeasured variables. Our study sample included women aged 40 and over, and results may not be generalizable to younger breast cancer patients. Although we collected information about participant’s inability to work, participants were not asked why they were unable to work. Our questionnaire captured critical information about socioeconomic factors, psychosocial factors such as social support, and clinical factors such as adjuvant therapies. However, we did not assess participants’ intentions to continue or discontinue employment during follow-up. We also did not collect information on employment status prior to breast cancer diagnosis and thus were unable to provide insight about how pre-diagnosis patterns correlated with post-diagnosis patterns. We combined full and part-time employment without differentiation, and although part-time workers may have been more likely to continue or resume employment than full-time workers, the small sample of part-time workers (14%) in our study sample prohibited us from investigating potential differences between the full- and part-time employment. Finally, we lacked detailed information about the type of employment (e.g. professional occupations versus service occupations) that would allow us to assess whether employment after treatment was influences by contextual factors such as job autonomy, schedule flexibility, physically demanding tasks, and organizational policies. These modifiable workplace factors could influence employment outcomes among early-stage breast cancer patients and should be considered in future studies.

Conclusions

In summary, fatigue, African-American race, non-private insurance status were associated with diminished employment participation among early-stage breast cancer patients two-years after surgical treatment. Future studies should examine facilitators and barriers to employment participation after breast cancer treatment, particularly among vulnerable subgroups. Moreover, because employment in the United States is associated with income and access to high-quality health care, research that investigates the relationships between employment participation and health-related outcomes (quality of life and adherence to treatment and screening guidelines) among breast cancer patients is needed. Early-stage breast cancer patients have a more favorable prognosis than late-stage patients, and future examinations into employment participation outcomes after treatment will be important for early-stage breast cancer research in the United States as the number of survivors increases in the coming decades.

Acknowledgments

Funding Information

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute and Breast Cancer Stamp Fund (R01 CA102777; PI: D.B. Jeffe) and supported in part by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Grant to the Healthier Workforce Center of the Midwest (U19 OH008868; PI: D. Rohlman) and the National Cancer Institute Postdoctoral Training in Cancer Prevention and Control (T32 CA190194; PI: G. Colditz) and the Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA91842; PI: T. Eberlein) to the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Funding Sources

National Cancer Institute and Breast Cancer Stamp Fund (R01 CA102777; PI: D.B. Jeffe)

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Healthier Workforce Center of the Midwest (U19 OH008868; PI: D. Rohlman)

National Cancer Institute Postdoctoral Training in Cancer Prevention and Control (T32CA190194; PI: G. Colditz)

National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support (P30 CA91842; PI: T. Eberlein)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Christine Ekenga: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing–original draft, and writing–review and editing.

Maria Pérez: Methodology, software, validation, investigation, data curation, and writing–review, project administration, and editing.

Julie Margenthaler: Methodology, investigation, resources, writing–review and editing

Donna Jeffe: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing–original draft, writing– review and editing, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2015-2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2014-2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez M, Schootman M, Hall LE, Jeffe DB. Accelerated partial breast irradiation compared with whole breast radiation therapy: a breast cancer cohort study measuring change in radiation side-effects severity and quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;162:329–342. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4121-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nekhlyudov L, Walker R, Ziebell R, Rabin B, Nutt S, Chubak J. Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: results from a multisite study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2016;10:1104–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guy GP, Jr, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3749–3757. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paalman CH, van Leeuwen FE, Aaronson NK, et al. Employment and social benefits up to 10 years after breast cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:81–87. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Boer AM, Taskila T, Ojajärvi A, van Dijk FH, Verbeek JM. Cancer survivors and unemployment: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. JAMA. 2009;301:753–762. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zajacova A, Dowd JB, Schoeni RF, Wallace RB. Employment and income losses among cancer survivors: Estimates from a national longitudinal survey of American families. Cancer. 2015;121:4425–4432. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rottenberg Y, Jacobs JM, Ratzon NZ, et al. Unemployment risk 2 years and 4 years following gastric cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ratzon NZ, Uziely B, de Boer AG, Rottenberg Y. Unemployment Risk and Decreased Income Two and Four Years After Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis: A Population-Based Study. Thyroid. 2016;26:1251–1258. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon LG, Beesley VL, Mihala G, Koczwara B, Lynch BM. Reduced employment and financial hardship among middle-aged individuals with colorectal cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2017;26:e12744–n/a. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul C, Boyes A, Hall A, Bisquera A, Miller A, O’Brien L. The impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment on employment, income, treatment decisions and financial assistance and their relationship to socioeconomic and disease factors. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016;24:4739–4746. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3323-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timperi AW, Ergas IJ, Rehkopf DH, Roh JM, Kwan ML, Kushi LH. Employment status and quality of life in recently diagnosed breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:1411–1420. doi: 10.1002/pon.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley CJ, Wilk A. Racial differences in quality of life and employment outcomes in insured women with breast cancer. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2013;8:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0316-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2011;77:109–130. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Muijen P, Weevers NLEC, Snels IAK, et al. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: a systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2013;22:144–160. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassett M, O’Malley A, Keating N. Factors influencing changes in employment among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:2775–2782. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blinder V, Eberle C, Patil S, Gany FM, Bradley CJ. Women With Breast Cancer Who Work For Accommodating Employers More Likely To Retain Jobs After Treatment. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36:274–281. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee MK, Kang HS, Lee KS, Lee ES. Three-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Factors Associated with Return to Work After Breast Cancer Diagnosis. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paalman CH, van Leeuwen FE, Aaronson NK, et al. Employment and social benefits up to 10 years after breast cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. British Journal of Cancer. 2016;114:81–87. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duijts SFA, van der Beek AJ, Bleiker EMA, Smith L, Wardle J. Cancer and heart attack survivors’ expectations of employment status: results from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:640. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4659-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch BM, Mihala G, Beesley VL, Wiseman AJ, Gordon LG. Associations of health behaviours with return to work outcomes after colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:865–870. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2855-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeffe DB, Perez M, Liu Y, Collins KK, Aft RL, Schootman M. Quality of life over time in women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ, early-stage invasive breast cancer, and age-matched controls. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:379–391. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson T, Rodebaugh TL, Perez M, Schootman M, Jeffe DB. Perceived social support change in patients with early stage breast cancer and controls. Health Psychol. 2013;32:886–895. doi: 10.1037/a0031894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Perez M, Schootman M, Aft RL, Gillanders WE, Jeffe DB. Correlates of fear of cancer recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1551-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Perez M, Schootman M, et al. A longitudinal study of factors associated with perceived risk of recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ and early-stage invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:835–844. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0912-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leitch AM, Dodd GD, Costanza M, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of breast cancer: update 1997. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 1997;47:150–153. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.47.3.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Econ. 1993;2:217–227. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730020305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouknight R, Bradley C, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:345–353. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balak F. Return to work after early-stage breast cancer: a cohort study into the effects of treatment and cancer-related symptoms. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:267–272. doi: 10.1007/s10926-008-9146-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blinder V. Employment after a breast cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of ethnically diverse urban women. J Community Health. 2012;37:763–772. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jagsi R, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term employment of survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1854–1862. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drolet M. Not working 3 years after breast cancer: predictors in a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8305–8312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen J. Breast cancer survivors at work. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:777–784. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318165159e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahn E. Impact of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on work-related life and factors affecting them. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:609–616. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carlsen K. Self-reported work ability in long-term breast cancer survivors. A population-based questionnaire study in Denmark. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:423–429. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.744877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tevaarwerk AJ, Lee JW, Sesto ME, et al. Employment outcomes among survivors of common cancers: the Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns (SOAPP) study. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice. 2013;7:191–202. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0258-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamminga SJ, Bültmann U, Husson O, Kuijpens JLP, Frings-Dresen MHW, de Boer AGEM. Employment and insurance outcomes and factors associated with employment among long-term thyroid cancer survivors: a population-based study from the PROFILES registry. Quality of Life Research. 2016;25:997–1005. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1135-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blinder V, Patil S, Eberle C, Griggs J, Maly RC. Early predictors of not returning to work in low-income breast cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140:407–416. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnsson A. Predictors of return to work ten months after primary breast cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2009;48 doi: 10.1080/02841860802477899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drolet M, Maunsell E, Brisson J, Brisson C, Mâsse B, Deschênes L. Not Working 3 Years After Breast Cancer: Predictors in a Population-Based Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:8305–8312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drolet M, Maunsell E, Mondor M, et al. Work absence after breast cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2005;173:765–771. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eaker S, Wigertz A, Lambert PC, Bergkvist L, Ahlgren J, Lambe M. Breast cancer, sickness absence, income and marital status. A study on life situation 1 year prior diagnosis compared to 3 and 5 years after diagnosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fantoni S. Factors related to return to work by women with breast cancer in northern France. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:49–58. doi: 10.1007/s10926-009-9215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnsson A. Predictors of return to work ten months after primary breast cancer surgery. Acta Oncol. 2009;48:93–98. doi: 10.1080/02841860802477899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, Nahar AM, Mohd Taib NA, Su TT. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(Suppl 3):S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S3-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnsson A. Factors influencing return to work: a narrative study of women treated for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2010;19:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beesley VL, Vallance JK, Mihala G, Lynch BM, Gordon LG. Association between change in employment participation and quality of life in middle-aged colorectal cancer survivors compared with general population controls. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1354–1360. doi: 10.1002/pon.4306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]