Abstract

Prolonged cold ischemia storage (CIS) is a leading risk factor for poor transplant outcome. Existing strategies strive to minimize IRI in transplanted organs, yet there is a need for novel approaches to improve outcomes of marginal allografts and expand the pool of donor organs suitable for transplantation. Aquaporins (AQPs) are a family of water channels that facilitate homeostasis, tissue injury and inflammation. We tested whether inhibition of AQP4 improves the survival of fully MHC-mismatched murine cardiac allografts subjected to 8 h CIS. Administration of a small molecule AQP4 inhibitor during donor heart collection and storage and for a short-time posttransplant improves the viability of donor graft cells, diminishes donor-reactive T cell responses and extends allograft survival in the absence of other immunosuppression. Furthermore, AQP4 inhibition is synergistic with CTLA4-Ig in prolonging survival of 8 h CIS heart allografts. AQP4 blockade markedly reduced T cell proliferation and cytokine production in vitro suggesting that the improved graft survival is at least in part mediated through direct effects on donor-reactive T cells. These results identify AQPs as a promising target for diminishing donor-specific alloreactivity and improving the survival of high-risk organ transplants.

Introduction

Ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) is an unavoidable consequence of solid organ transplantation. The negative impact of IRI on cells and tissues arise from the complex network of events including oxygen and nutrient deprivation, disruption of cellular homeostasis, reactive oxygen species generation and inflammation (1). In addition, IRI directly or indirectly enhances anti-donor cellular and humoral responses. Prolonged cold ischemia storage (CIS) is an independent risk factor for poor transplant outcome. CIS is associated with early graft loss and increased incidence of acute and chronic rejection (2–5). Patients receiving transplants subjected to long-term CIS are commonly treated with more aggressive immunosuppression. Furthermore, some solid organ allografts subjected to prolonged CIS are considered high-risk and are not transplanted, exacerbating the problem of organ shortage. Current therapeutic options specifically controlling ischemia reperfusion injury are limited to organ pretreatment and modified perfusion and preservation conditions.

Aquaporins (AQPs) are water channels that facilitate passive water transfer across the cell membrane in response to osmotic gradients. In mammals, there are 13 AQP family members (AQP0 – AQP12), with AQPs 3, 7, and 9 transporting glycerol and other small molecules in addition to water (aquaglyceroporins) (6–8). AQPs are expressed in all tissues and organs and are involved in many physiological processes including urine concentration, brain water homeostasis, angiogenesis, neural excitability and cell migration (8). Recent studies demonstrate roles of several aquaglyceroporins in innate and adaptive immunity. AQPs 3 and 7 are expressed by immature dendritic cells (DCs) and facilitate antigen uptake through micropinocytosis (9). AQP3 is expressed in T cells and macrophages and is required for chemokine-dependent cell migration (10, 11). Aquaglycerol channel AQP9 is up-regulated in activated CD8 T cells and is critical for the development of T cell memory (12).

AQP4 expression was initially described in renal collective ducts, renal epithelial cells, and brain astrocytes (13). AQP4 is also expressed by cardiomyocytes, and AQP4 deficiency results in reduced myocardial tissue damage and edema during infarct (14, 15). These findings suggest that blocking AQP4 may attenuate IRI as well as innate and adaptive immune responses following transplantation. However, the possibility of blocking water channels with the purpose of improving transplant survival has not been previously explored, largely due to the lack of reagents selectively targeting specific aquaporins.

The goal of our study was to investigate whether inhibition of AQP4 alone or in combination with other therapies can be used to prolong survival of high-risk mouse cardiac allografts. We used a small molecule inhibitor that specifically blocks AQP4, with limited inhibition of AQP1 and AQP5. To approximate a clinical situation in a mouse transplant model, donor heart allografts were subjected to 8 h of cold ischemia storage. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, blocking AQP4 during donor heart collection and storage and for a short-time posttransplant improves did not affect the early expression of inflammatory markers characteristic of IRI. Nevertheless, AQP4 inhibition improved the viability of donor graft cells after 8 h of cold ischemic storage, diminished anti-donor T cell responses and prolonged allograft survival in the absence of other immunosuppression. Furthermore, AQP4 inhibition enhanced the efficacy of CTLA4-Ig costimulatory blockade in prolonging the survival of heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS. Our results suggest that the graft prolonging effects of AQP4 blockade are at least in part mediated through the direct inhibition of donor-reactive T cell expansion and cytokine production.

Methods

Animals

Male and female C57BL/6J (H-2b) [B6], BALB/cJ (H-2d) [BALB/c] and SJL/J-Pde6brd1 (H2s) mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). All animals were maintained and bred in the pathogen-free facility at the Cleveland Clinic. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Cleveland Clinic.

Heart transplantation

Vascularized heterotopic cardiac transplants were performed as previously described (16, 17). BALB/c heart allografts were preserved in University of Wisconsin (UW) solution (320 mOsm, Preservation Solutions Inc., Elkhorn, WI), or in Ringer’s lactate solution (309 mOsm, Baxter International, Deerfield, IL) for 8 h at 4°C prior to transplantation into fully MHC mismatched B6 mice. For costimulatory blockade, recipients were injected i.p. with 250 µg CTLA4-Ig on days 0 and 1 posttransplant (BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH). Rejection was defined as a loss of palpable heartbeat and confirmed by laparotomy.

Aquaporin inhibitors

A small molecule inhibitor of AQP4, AER-270, was identified by high throughput screening. Briefly, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell-lines expressing N-terminal FLAG tagged human AQP1, AQP4a, AQP4b, AQP5, mouse AQP4-M23, or unrelated protein CHO-CD81 were generated using the Flp-InTM system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and subjected to hypoosmotic shock and water permeability assessment. A phosphorylated prodrug derivative of AER-270, AER-271, has >5000-fold improved water solubility compared to the parent drug (Farr et al., submitted for publication). Upon in vivo administration, AER-271 is rapidly converted to AER-270 by endogenous phosphatases.

BALB/c heart allograft donors received a single injection of AER-271 (10 mg/kg i.p.) 30 min prior to sacrifice. Collected hearts were perfused with and stored in UW or Ringer’s solution supplemented with 10 µM AER-270 for 8 h on ice. Control hearts were collected from BALB/c mice injected with PBS and stored in UW or Ringer’s solution without additives. Recipients were injected with AER-271 (10 mg/kg i.p.) every 6 h on d. 0–5 posttransplant starting at 30 min after surgery, for a total of 20 injections. Injection of PBS with a similar frequency and duration did not alter the course of heart allograft rejection compared to untreated recipients (data not shown), thus untreated recipients were used as controls in all subsequent experiments. During in vitro ELISPOT and T cell proliferation assays, 0.125 µM to 10 µM AER-270 was added to the culture media.

Flow cytometry

Fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs and PE-conjugated Annexin V were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For AQP4 detection, polyclonal goat anti-mouse/rat/human AQP4 IgG (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled donkey anti-goat IgG (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were used. Spleen or graft infiltrating cells were isolated and stained as previously described (18–20). At least 200,000 events/sample were acquired on a BD Bioscience LSRII followed by data analysis using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

ELISPOT assays

IFNγ ELISPOT assays were performed as previously described using capture and detecting anti-mouse cytokine antibody from BD Biosciences (20–22). Recipient spleen cells were stimulated with mitomycin C-treated donor BALB/c or third party SJL spleen cells for 24 h. The resulting spots were analyzed using an ImmunoSpot Series 4 analyzer (Cellular Technology, Cleveland, OH).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Portions of heart allografts were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Spleen CD4+ and CD8+ cells were purified using negative selection mouse T cell isolation kit from STEMCELL technologies (Vancouver, Canada) followed by staining for CD4, CD8 and CD44 markers and flow sorting (FACSAria, BD Biosciences). Total RNA was isolated from individual samples using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription was performed using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit, quantitative real-time PCR was done on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System instrument using Taqman Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (2×), No AmpEraseUNG (all from Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Probes and primers were from Taqman gene expression assay reagents (Applied Biosystems). Data were normalized to Mrpl 32 (Mm00777741-sH) RNA amplification and calculated relative to the expression of the target gene in heart tissue from naïve B6 mice.

T cell proliferation assay

Flat-bottom 96-well plates pre-coated with anti-mouse CD3 (clone 2C11, 2µg/ml, e-Bioscience, San Diego CA) and anti-mouse CD28 (clone 37.51, 4µg/ml, e-Bioscience) overnight at 4°C. T cells isolated from spleens of naïve B6 mice using negative selection mouse T cell isolation kit from STEMCELL technologies (Vancouver, Canada) were labeled with CFSE as previously published (23), and 0.1×106 aliquots were cultured on anti-CD3/anti-CD28 pre-coated plates at 37°C. AER-270 at 0.125 – 10 µM or DMSO diluent (equivalent to DMSO content in 10 µM AER-270 dilution) was added to the wells. Cells were harvested after 72 h and CFSE dilution was assessed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Heart allograft survival was compared between groups by Kaplan-Meier analysis. Differences between groups during recall immune responses were analyzed using a non-parametric equivalent of one-way ANOVA, the Kruskal-Wallis test. When the overall p value was <0.05, pairwise comparisons were carried out using Mann-Whitney test. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

AQP4 inhibition during cold ischemia storage reduces cell apoptosis in explanted donor heart

A small molecule inhibitor of AQP4, AER-270, was identified by high throughput screening. AER-270 inhibited AQP4a and AQP4b (60.5±1.4% and 55.2±1.6% inhibition, respectively) and mouse AQP4-M23 (52.0±2.0%) water permeability, with only limited inhibition of AQP1 (16.2±1.1%) and AQP5 (7.5 ±0.7%). A phosphorylated prodrug derivative of AER-270, AER-271, has >5000-fold improved water solubility compared to the parent drug (Farr et al., submitted for publication). Upon in vivo administration, AER-271 is rapidly converted to AER-270 by endogenous phosphatases. Peak plasma concentrations of AER-270 are 500 ng/ml, or 1.75 µM 20 min after i.p. injection of 10 mg/kg AER-271 into C57BL/6 mice, which then rapidly decreases to 0.5 µM by 60 min and to 0.15 µM by 2 h after injection (not shown).

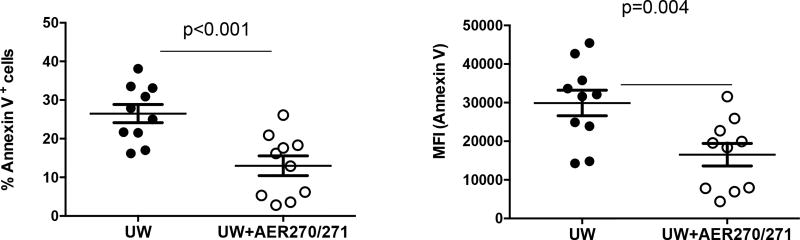

To test the effects of AQP4 inhibition during heart graft collection and storage, donor mice received single injection of AER-271 30 min prior to sacrifice. Collected hearts were perfused with and stored in UW solution supplemented with 10 µM AER-270 for 8 h on ice. AER-270/271 treatment markedly reduced cardiac cell apoptosis compared to control hearts collected from PBS-injected donors and stored in UW without additives (Figure 1).

Figure 1. AQP4 inhibition during cold ischemia storage reduces cell apoptosis in explanted donor heart.

BALB/c heart donors were injected with AER-271 0.5 h prior to organ collection. Hearts were explanted, perfused and stored on ice for 8 h in UW solution ± 10 µM AER-270. Single cell suspensions were prepared by collagenase/DNAse I digestion and analyzed for Annexin V staining by flow cytometry. The results are presented for individual hearts.

AQP4 blockade prolongs survival of heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS

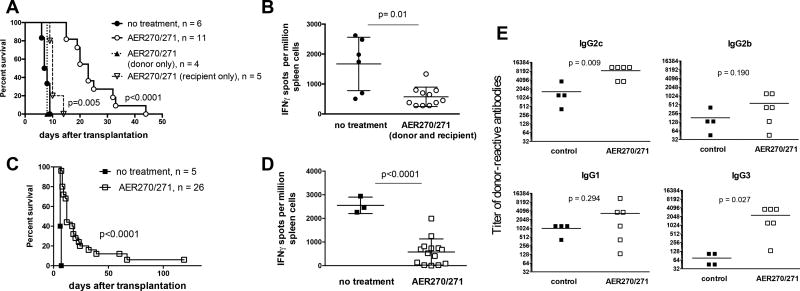

We next tested whether increased cell viability observed in AER-270/271 treated donor hearts results in improved transplant outcome. BALB/c heart allografts treated with AER-270/271 during retrieval and 8 h CIS in UW solution were transplanted into fully MHC mismatched B6 mice, followed by AER-271 recipient treatment for the first 5 days posttransplant. AQP4 inhibition significantly prolonged survival of heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS in the absence of other immunosuppression (MST of 23 vs 7.5 d, Figure 2A). AER-270/271 treatment of donor hearts in the absence of recipient treatment had no effect on allograft survival (MST of 7 d, Figure 2A), whereas B6 recipients receiving untreated BALB/c heart allografts but injected with AER-271 after transplantation revealed only modest graft prolongation (MST of 9 d, Figure 2A). Recipients treated with AER-271 had markedly reduced frequencies of IFNγ producing donor-reactive T cells at the time of rejection (Figure 2B). This was not due to the systemic lymphocyte depletion as the numbers of spleen T lymphocytes were comparable in control and AER-271 injected mice on day 3 and at the end of the treatment (16.5 ± 0.8 × 106 vs 14.0 ± 1.0 × 106 for CD4 T cells and 7.3 ± 0.3 × 106 vs 7.8 ± 0.5 × 106 for CD8 T cells). Similar improved graft survival and decreased priming of donor-reactive T cells were observed for heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS in Ringer’s lactate, a solution commonly used in rodent organ transplantation (Figure 2C–D) (24, 25). Despite impaired T cell alloimmunity, recipients treated with AER-271 developed donor-reactive IgG alloantibodies (Figure 2E).

Figure 2. AQP4 blockade prolongs survival of heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS.

BALB/c heart donors were injected with AER-271 0.5 h prior to organ collection. Hearts were explanted, perfused and stored on ice for 8 h in UW (A–B) or Ringer’s (C–E) solution ± 10 µM AER-270 prior to transplantation into B6 recipients. AER-270/271 recipients received donor hearts stored with AER-270 and were injected with 10 mg/kg AER-271 i.p. every 6 h for 5 days after transplantation (open circles). Control recipients were transplanted with hearts stored without AER-270 and were not treated (closed circles). Treatment of the control recipients with i.p. injections of PBS every 6 h for 5 days posttransplant did not alter the kinetics of allograft survival (data not shown). Two additional groups either received AER-270-treated donor hearts without the recipient treatment (closed triangles) or were transplanted with untreated donor hearts but received AER-271 injections after transplantation (open inverted triangles). A, C. Heart allograft survival. P values are indicated versus untreated group. B, D. The frequencies of donor-reactive IFNγ secreting spleen cells at the time of rejection. E. The serum titers of donor-reactive IgG alloantibodies at the time of rejection. The titers of third party SJL-reactive IgG alloantibodies were < 135 for all IgG isotypes in all samples. Symbols represent data for individual recipients.

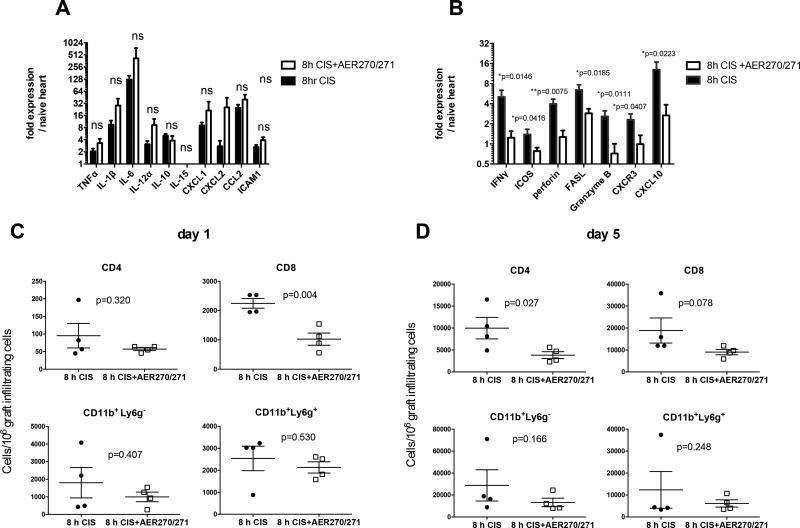

AER-270/271 treatment inhibits early CD8 T cell infiltration into heart allografts

Based on the demonstrated role of AQP4 during brain and heart ischemia (14, 26), we hypothesized that AQP4 blockade ameliorates the consequences of ischemia reperfusion injury and thus extends transplant survival. Unexpectedly, AQP4 inhibition did not alter the intragraft expression of inflammatory markers typically found in ischemia/reperfusion injury at 24 h posttranspant including cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and CCL2, and adhesion molecule ICAM-1 (Figure 3A). In contrast, AER-270/271 treatment significantly reduced expression of molecules associated with T cell activation, migration and function such as CXCR3, ICOS, IFNγ, Granzyme B, perforin, FasL, and IFNγ-induced chemokine CXCL10 (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the graft-infiltrating cells in recipients treated with AER-270/271 contained fewer CD8+ T cells compared to control heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS (Figure 3C). These data suggest that the AQP4 blockade inhibits early infiltration of endogenous memory CD8 T cells into heart allografts, an event that precedes priming of donor-reactive T cells in the spleen (27). As anticipated, the numbers of graft-infiltrating T cells increased by day 5 after transplantation. At that point, both CD4 and CD8 T cell infiltration was reduced by AER-270/271 treatment (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. AER-270/271 treatment inhibits early CD8 T cell infiltration into heart allografts.

Heart allograft procedure and treatments were performed as in Figure 2B, and grafts were collected at 24 h posttransplant. A–B. Intragraft expression of ischemia/reperfusion injury markers (A) and factors associated with T cell activation (B) were determined by real time RT-PCR. C–D. Graft-infiltrating cells were isolated at 24 h (C) or on day 5 (D) posttranplant and analyzed by flow cytometry. N = 4 animals/group. The experiments were performed twice with similar results.

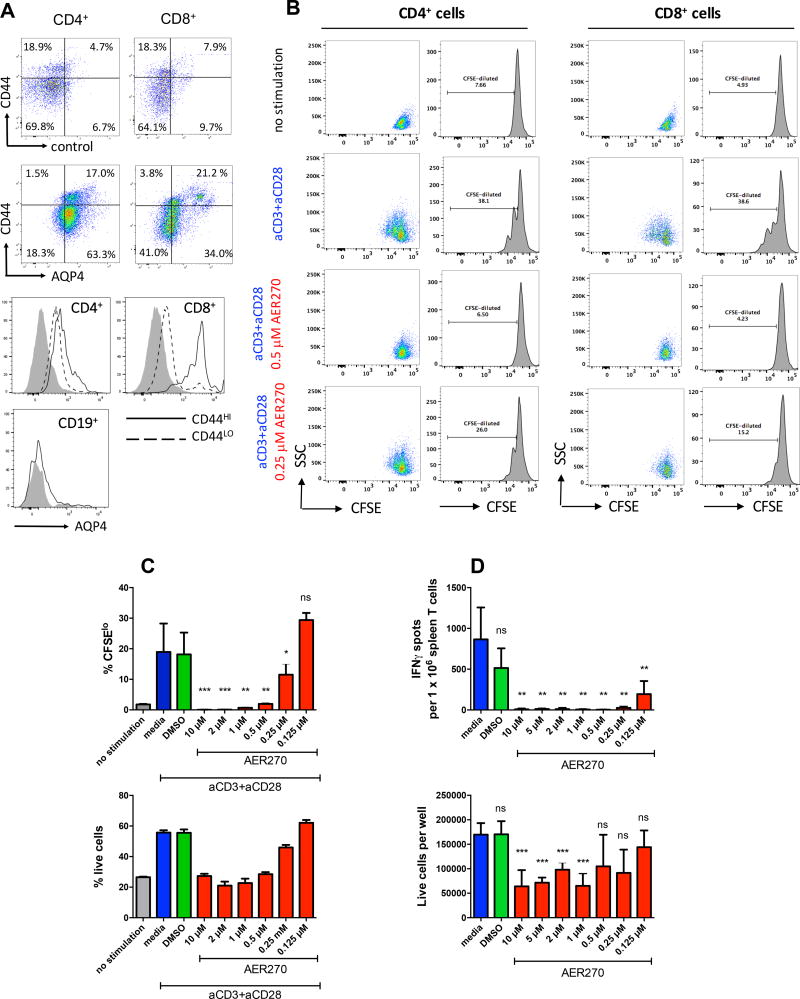

AQP4 blockade by AER-270/271 directly inhibits T cell proliferation and effector functions

Flow cytometry analysis of naïve B6 splenocytes revealed AQP4 expression on both CD4 and CD8 T cells, but not on B cells (Figure 4A). In both CD4 and CD8 subsets, CD44hi effector/memory T cells expressed higher levels of AQP4 compared to CD44lo naïve T cells. AQP4 expression was also detected on a proportion of CD11b+ and CD11c+ spleen cells (data not shown).

Figure 4. AQP4 blockade by AER-270/271 directly inhibits T cell proliferation and effector functions.

A. Flow cytometry analysis of AQP4 expression on CD4+, CD8+ and CD19+ mouse spleen cells. Representative dot plots (top) and histograms (bottom) are shown for three independent experiments. Control stainings were performed with secondary anti-goat IgG antibody in the absence of primary goat anti-AQP4 (top row dot plots and shaded histograms). B–C. Spleen T cells isolated from naïve B6 mice were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAb for 72 h. CFSE dilution was evaluated by flow cytometry. B. Representative histograms and dot plots shown after gating on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. C. Percent of CFSElo cells (top). Cell viability was assessed by acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining and expressed as percent of live cells (bottom). D. Spleen cells isolated from B6 recipients of BALB/c heart allografts on d. 7 posttransplant were tested in a recall IFNγ ELISPOT assay against mitomycin C treated BALB/c stimulator cells. Top – IFNγ spots per 1 × 106 plated cells. Bottom – the numbers of live cells per well at the end of 24 h culture. ns – not significant, p>0.05; * - p<0.05; ** - p<0.01; *** - p<0.001. All experiments were performed at least twice with similar results.

Consistent with the AQP4 presence on T cells, AER-270 directly inhibited CD4 and CD8 T cell proliferation induced by anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mAb (Figure 4B–C). To test whether AQP4 blockade affects recall responses by previously activated alloreactive T cells, we isolated spleen cells from B6 recipients of BALB/c heart allografts and tested them by IFNγ ELISPOT assay against BALB/c alloantigens (Figure 4D). AER-270 inhibited IFNγ production by previously primed T cells in a range of concentrations (0.125–10 µM). After 24 h culture, AER-270 reduced the numbers of live cells at 1–10 µM, but not at 0.125–0.5 µM indicating that IFNγ inhibition was not entirely due to the decreased cell viability.

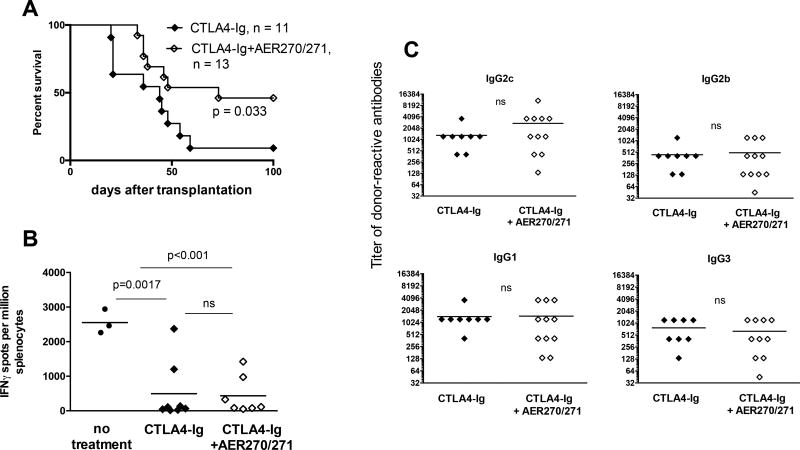

AQP4 inhibition is synergistic with CTLA4-Ig to prolong the survival of heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS

We have previously reported that subjecting mouse heart allografts to 8 h CIS interfered with graft-prolonging effects of costimulatory blockade, mainly due to reactivation of endogenous memory CD8 T cells (17). We therefore tested whether a short peritransplant treatment with AQP4 inhibitor improves the efficacy of CTLA4-Ig in these settings. Consistent with our previous findings, the majority of B6 recipients rejected 8 h CIS BALB/c heart allografts despite CTLA4-Ig treatment, with only one out of 11 grafts surviving beyond 100 days (MST of 44 d). The addition of AQP4 blockade to CTLA4-Ig treatment significantly improved the transplant outcome with long-term survival in 6 out of 13 recipients (MST of 73 d). At the time of graft rejection (or at sacrifice on d. 100 if rejection did not occur earlier), recipients treated with CTLA4-Ig alone or with the combination of AER-270/271 and CTLA4-Ig had comparable low frequencies of donor-reactive IFNγ producing spleen cells but similar serum titers of donor-reactive IgG alloantibodies (Figure 5B–C).

Figure 5. AQP4 inhibition synergizes with CTLA4-Ig to prolong the survival of heart allografts subjected to 8 h CIS.

BALB/c heart allografts were collected, perfused and stored for 8 h ± 10 µM AER-270 as described for Figure 2. B6 recipients transplanted with AER-270-treated hearts were injected with CTLA4-Ig (250 µg i.p. on days 0 and 1) and with AER-271 (10 mg/kg i.p. every 6 h for 5 days posttransplant, open diamonds). Recipients transplanted with untreated donor hearts received only CTLA4-Ig treatment (closed diamonds). A. Heart allograft survival. B. The frequencies of donor-reactive IFNγ secreting spleen cells at the time of rejection. C. The serum titers of donor-reactive IgG alloantibodies at the time of rejection. The titers of third party SJL-reactive IgG alloantibodies were < 135 for all IgG isotypes in all samples. Symbols represent data for individual recipients. ns – p > 0.05.

Discussion

Our study was prompted by recent findings that AQP4 is expressed on cardiac myocytes and is protective during ischemic cardiac tissue injury (14). Treatment of donor hearts with the AQP4 inhibitor during collection, perfusion and storage significantly reduced the rate of cellular apoptosis. This is consistent with the demonstration that AQP4 deficiency improves myocyte survival in acute myocardial IRI (14). In combination with a short-course peritransplant AER-271 administration, the improved viability of donor heart tissue resulted in significantly improved allograft survival despite extended CIS. Notably, the survival of untreated donor hearts subjected to 8 h CIS was only modestly albeit significantly prolonged despite the recipient treatment after transplantation (Figure 2A). Thus, inhibition of donor heart cell death during prolonged CIS is a necessary mechanism of the observed graft prolongation. In a pilot experiment, we assessed whether AQP4 blockade improves viability of human heart tissue. Addition of AER-270 to UW storage solution reduced apoptotic cell death in small left ventricle fragments from discarded human hearts incubated on ice for 8 h (data not shown) suggesting that AQP4 blockers might be a beneficial component of organ preservation solutions in the future.

Unexpectedly, AQP4 inhibition did not alter the expression of typical IRI markers such as proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules. However, AER-270/271 treatment ameliorated another important consequence of prolonged CIS. Previous studies by our group indicate that following transplantation of 8h CIS heart allografts, endogenous memory CD8 T cells rapidly infiltrate into and expand within the graft tissue and precipitate costimulatory-blockade resistant rejection (17, 27, 28). AQP4 blockade not only inhibited early CD8 T cell infiltration and activation within the graft, but also improved the efficacy of CTLA4-Ig treatment in recipients of 8 h CIS heart allografts (Figure 5).

Another unexpected finding was that the priming of IFNγ producing donor-reactive T cells in the spleen was markedly inhibited by AER-270/271 treatment. Furthermore, recipient treatment with AER-271 for the first 5 days after transplantation was critical for improved graft survival (Figure 2A) underscoring the importance of modulating anti-donor immune responses. Analysis of spleen and lymph node cells following AER-271 administration did not reveal systemic lymphocyte depletion (data not shown), and in vitro T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion were inhibited by AER-271 (Figure 4) suggesting that intact AQP4 function is required for T cell activation, expansion and/or effector functions.

Despite reduced T cell priming, AER-270/271 treated recipients developed high serum titers of IgG DSA by the time of rejection suggesting that combining AQP4 inhibitors with B cell targeting therapies (such as Rituximab) may further extend allograft survival. As B cells do not express AQP4, our future studies will address the effect of AQP4 inhibition of CD4 helper T cells and test for possible changes in the DSA response.

Our results do not rule out the possibility that in vivo AER-271 treatment may affect other hematopoietic or non-hematopoietic cell subsets thus contributing to allograft prolongation. In fact, we detected AQP4 expression in CD11c+ and CD11b+ cell subsets by flow cytometry (data not shown). Ongoing studies will test the potential role of AQP4 in antigen presenting cells and innate effector cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages, in the context of transplantation.

Our study provides the first demonstration that AQP4 is expressed on CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes, and that inhibition of AQP4 modulates T cell activation and function. These findings identify a new direction for future studies in transplant therapy. The potency of short-term AQP4 inhibition in a robust model of heart allograft rejection makes it a promising strategy for improving survival of marginal organ transplants in combination with other forms of immunosuppression.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by NIH grants 1P01 AI087586 and 1R01 AI113142-01A1 (A.V.) and RO1 AI40459 (R.L.F.).

Abbreviations

- AQP

aquaporin

- CIS

cold ischemia storage

- DC

dendritic cell

- IRI

ischemia/reperfusion injury

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors of this manuscript have conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. George W. Farr, Paul R. McGuirk and Marc F. Pelletier are employees of Aeromics, Inc, Cleveland, OH. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Slegtenhorst BR, Dor FJ, Rodriguez H, Voskuil FJ, Tullius SG. Ischemia/reperfusion Injury and its Consequences on Immunity and Inflammation. Curr Transplant Rep. 2014;1(3):147–154. doi: 10.1007/s40472-014-0017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucek MM, Aurora P, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, Trulock EP, Christie J, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: tenth official pediatric heart transplantation report--2007. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2007;26(8):796–807. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debout A, Foucher Y, Trebern-Launay K, Legendre C, Kreis H, Mourad G, et al. Each additional hour of cold ischemia time significantly increases the risk of graft failure and mortality following renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2015;87(2):343–349. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salahudeen AK, Haider N, May W. Cold ischemia and the reduced long-term survival of cadaveric renal allografts. Kidney Int. 2004;65(2):713–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tullius SG, Reutzel-Selke A, Egermann F, Nieminen-Kelha M, Jonas S, Bechstein WO, et al. Contribution of prolonged ischemia and donor age to chronic renal allograft dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(7):1317–1324. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1171317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borgnia M, Nielsen S, Engel A, Agre P. Cellular and molecular biology of the aquaporin water channels. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:425–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishibashi K, Hara S, Kondo S. Aquaporin water channels in mammals. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2009;13(2):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s10157-008-0118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verkman AS, Anderson MO, Papadopoulos MC. Aquaporins: important but elusive drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(4):259–277. doi: 10.1038/nrd4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Baey A, Lanzavecchia A. The role of aquaporins in dendritic cell macropinocytosis. J Exp Med. 2000;191(4):743–748. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hara-Chikuma M, Chikuma S, Sugiyama Y, Kabashima K, Verkman AS, Inoue S, et al. Chemokine-dependent T cell migration requires aquaporin-3-mediated hydrogen peroxide uptake. J Exp Med. 2012;209(10):1743–1752. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu N, Feng X, He C, Gao H, Yang L, Ma Q, et al. Defective macrophage function in aquaporin-3 deficiency. FASEB J. 2011;25(12):4233–4239. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-182808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cui G, Staron MM, Gray SM, Ho PC, Amezquita RA, Wu J, et al. IL-7-Induced Glycerol Transport and TAG Synthesis Promotes Memory CD8+ T Cell Longevity. Cell. 2015;161(4):750–761. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verkman AS. Aquaporins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 13):2107–2112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.079467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutkovskiy A, Stenslokken KO, Mariero LH, Skrbic B, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Hillestad V, et al. Aquaporin-4 in the heart: expression, regulation and functional role in ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107(5):280. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warth A, Eckle T, Kohler D, Faigle M, Zug S, Klingel K, et al. Upregulation of the water channel aquaporin-4 as a potential cause of postischemic cell swelling in a murine model of myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2007;107(4):402–410. doi: 10.1159/000099060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. In vivo helper functions of alloreactive memory CD4+ T cells remain intact despite donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD40 ligand therapy. J Immunol. 2004;172(9):5456–5466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su CA, Iida S, Abe T, Fairchild RL. Endogenous memory CD8 T cells directly mediate cardiac allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(3):568–579. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayasoufi K, Fan R, Fairchild RL, Valujskikh A. CD4 T Cell Help via B Cells Is Required for Lymphopenia-Induced CD8 T Cell Proliferation. J Immunol. 2016;196(7):3180–3190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorbacheva V, Fan R, Li X, Valujskikh A. Interleukin-17 promotes early allograft inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(3):1265–1273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q, Chen Y, Fairchild RL, Heeger PS, Valujskikh A. Lymphoid sequestration of alloreactive memory CD4 T cells promotes cardiac allograft survival. J Immunol. 2006;176(2):770–777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casey KA, Fraser KA, Schenkel JM, Moran A, Abt MC, Beura LK, et al. Antigen-independent differentiation and maintenance of effector-like resident memory T cells in tissues. J Immunol. 2012;188(10):4866–4875. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang QW, Rabant M, Schenk A, Valujskikh A. ICOS-Dependent and -independent functions of memory CD4 T cells in allograft rejection. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(3):497–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayasoufi K, Yu H, Fan R, Wang X, Williams J, Valujskikh A. Pretransplant antithymocyte globulin has increased efficacy in controlling donor-reactive memory T cells in mice. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2013;13(3):589–599. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanchard JM, Pollak R. Techniques for perfusion and storage of heterotopic heart transplants in mice. Microsurgery. 1985;6(3):169–174. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920060308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JJ, Hockenheimer S, Bickerstaff AA, Hadley GA. Murine renal transplantation procedure. J Vis Exp. 2009;(29) doi: 10.3791/1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manley GT, Fujimura M, Ma T, Noshita N, Filiz F, Bollen AW, et al. Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2000;6(2):159–163. doi: 10.1038/72256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schenk AD, Nozaki T, Rabant M, Valujskikh A, Fairchild RL. Donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells infiltrate cardiac allografts within 24-h posttransplant in naive recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(8):1652–1661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schenk AD, Gorbacheva V, Rabant M, Fairchild RL, Valujskikh A. Effector functions of donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells are dependent on ICOS induced during division in cardiac grafts. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(1):64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]