Abstract

Purpose

To develop a new MRI method to detect and characterize brain abscesses using the CEST contrast inherently carried by bacterial cells, namely bacCEST.

Methods

Bacteria S. aureus (ATCC #49775) and F98 glioma cells were injected stereotactically in the brains of F344 rats to form abscesses and tumors. The CEST signals of brain abscesses (n=4) and tumors (n=4) were acquired using two B1 values (i.e., 1 and 3 μT) and compared. The bacCEST signal of the brain abscesses in the rats (n=3) receiving ampicillin (i.p. 40 mg/kg twice daily) was acquired before, 4 and 10 days after the treatment.

Results

The bacCEST signal of S. aureus was characterized in vitro as a strong and broad signal in the range of 1 to 4 ppm, with the maximum contrast occurring at 2.6 ppm. The CEST signal in S. aureus-induced brain abscesses was significantly higher than that of contralateral parenchyma (P=0.003). Moreover, thanks to their different B1-independece, brain abscesses and tumors could be effectively differentiated (P=0.005) using ΔCEST(2.6ppm,3μT-1μT), defined by the difference between the CEST signal (offset=2.6ppm) acquired using B1 = 3 μT and that of 1 μT. In treated rats, bacCEST MRI could detect the response of bacteria as early as 4 days after the antibiotic treatment (P=0.035).

Conclusion

BacCEST MRI provides a new imaging method to detect, discriminate and monitor bacterial infection in deep-seated organs. Because no contrast agent is needed, such an approach has a great translational potential for detecting and monitoring bacterial infection in deep-seated organs.

Keywords: MRI, CEST, bacterial infection, brain abscess

Introduction

Brain abscess is a severe central nervous system disorder and the most common focal suppurative brain infection (1,2). While there has been a significantly reduced mortality in recent years, thanks to advances in modern neuroradiological diagnosis and neurosurgical and antimicrobial therapy (3–5), the mortality is still relatively high (19–43%) and highly dependent on etiology (6). For abscesses with an intraventricular extension, for example, mortality is up to 80%. Quick and accurate diagnosis at the earliest stage is critical to direct the appropriate treatment of brain bacterial infections. However, effective differentiation of brain abscesses from other brain disorders, such as brain tumors (cystic malignancy) and neuroinflammation, is still challenging because of their similarity in clinical symptoms, and pathologic and radiological characteristics (7). Most conventional medical imaging methods rely on either morphological changes or contrast enhancement characteristics, which are unfortunately unable to detect brain abscesses specifically. For example, in the late stage of bacterial infection, the formation of brain abscess shows MRI manifestation as a typical rim-like enhancement, which is often similar to necrotic malignant tumors, especially glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) (8). Classically, an abscess has a thin, regular enhancing capsule and a tumor is likely to have a thick or nodular capsule--but many exceptions exist and often lead to ambiguous diagnoses, indicating that more advanced imaging methods are required.

In the past decades, tremendous efforts have been made to develop specific molecular imaging methods to detect bacterial infections using computed tomography (CT) (9), MRI (10,11), fluorescence imaging (12), bioluminescence imaging (BLI) (13,14), and positron emission tomography (PET) (15,16). However these methods rely on the use of injectable contrast agents, which limit their applications in poorly perfused tissues (17). Moreover, clinical translation of new exogenous agents is challenging and may take long due to the approval process (18,19). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a non-contrast-agent based imaging technology that could overcome these difficulties and potentially improve the clinical management of bacterial infection in deep organs. In the clinic, several functional MRI methods have been reported to visualize pyogenic brain lesions or discriminate them from other neural disorders. For instance, diffusion-weighted (DWI) MRI has been suggested to differentiate brain abscess from primary, cystic, or necrotic tumors (20), based on the limited free motion of water molecules in the viscous milieu in the necrotic center of abscess cavity. Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion-weighted MRI was shown to discriminate tumor and abscess by their different relative cerebral blood volumes(8). Unfortunately, none of these MR methods are specific to bacterial infection, and unable to differentiate different brain abscesses by etiology. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is another potential method to detect bacterial infection, to differentiate bacterial infection, and even possibly to differentiate anaerobic brain abscesses from aerobic abscesses on the basis of metabolite patterns (21–25). However, MRS approaches are often limited by low detection sensitivity, and resulting low spatial and temporal resolution. Because the identification of the presence of a pathogen is crucial to determine antibiotic susceptibility patterns and tailor antibiotic treatment, a non-invasive MRI method to more specifically detect bacterial infection and identify the pathogens is still an unmet clinical need.

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) (26–29) is a recently developed MRI technique that enables the sensitive detection of a variety of molecules with exchangeable protons through the changes in water signal, providing a new pathway for molecular MR imaging. Recently, we successfully developed a “bacterial CEST” (bacCEST) MRI approach to detect bacterial infection in a tumor directly using the endogenous CEST MRI contrast generated by bacteria (30). This method requires no exogenous imaging probes, which is particularly useful for application to deep organs like brain and bone marrow where contrast agents are difficult to reach. In the current study, we aimed to expand the utility of bacCEST to the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of brain abscess formed by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), one of the most common causes of brain abscesses and other life-threatening infections (31). Using a rat brain abscess model, we show that bacCEST can detect bacterial abscesses and demonstrate the ability to differentiate brain abscess from brain tumor. Moreover, we show the feasibility of using bacCEST MRI to monitor the bacterial response to treatment.

Methods

Cell culture

Both rat F98 and 9L glioma cells were cultured in DMEM media (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Cultures of pathologic S. aureus (ATCC, no. 49775) were prepared by overnight growing at 37°C in 12ml of ATCC® Medium 1806 culture broth. The bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000 g for 15 minutes, washed twice in sterile PBS, and resuspended in PBS to the desired concentrations.

Animals

All animal experimental protocols are approved by Johns Hopkins Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 15 rats was used as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of animals used in the study

| Single implementation | Double | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abscess | Non-treatment | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Treatment (ampicillin) | 3 | 3 | ||

| Treatment (saline) | 3 | 3 | ||

| Tumor | F98 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 9L | 3 | 3 |

Brain abscess model

F344 Fisher rats (6-week-old, female, 100–150 g, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) were were anesthetized using a previously published procedure (32) and injected stereotactically (left frontal lobe, 3 mm lateral and 2 mm anterior of Bregma, 1.0 μL/min injection rate, injection volume= 2 μL) with 6×106 S. aureus packaged as agarose beads(33). MR imaging was performed around 9 days after the implantation, when the bacterial abscess was well circumscribed from the surrounding brain parenchyma and the extent of edema was mild (33).

Antibiotic treatment

Six rats were selected randomly into two groups to receive intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of ampicillin (40 mg/kg) or saline twice daily for 10 days. The CEST MRI was carried out before, 4 and 10 days after the treatment.

Brain tumor model

Using the same procedure described above, four F344 Fisher rats were anesthetized and stereotactically implanted with 5×104 F98 cells or 5×105 9L cells in the right frontal lobe located 3 mm lateral and 2 mm anterior to the Bregma. To directly compare the endogenous CEST contrast between tumors and bacterial abscess, two of them were also induced with S. aureus on the contralateral side. MR imaging was performed around 12 days after the tumor inoculation.

MR

All MR images were acquired on an 11.7 T Bruker Biospec horizontal bore scanner (Bruker Biosciences, Billerica, MA) equipped with a rat brain surface array RF coil (receiver) and a 72mm volume coil (T11232V3, transmitter). For each animal, T2w images were first acquired to assess the formation and extent of bacteria abscesses using a RARE sequence with a RARE factor of 20 (TR/TE=3000/100 ms), slice thickness=1 mm, acquisition matrix size=256×256, FOV=25×25 mm, and NA=2 (total acquisition time=2 min 40 sec). Z-spectral (saturation spectra as a function of irradiation frequency) images were acquired using a modified RARE sequence (TR=5.0 sec, effective TE=5 ms, RARE factor=10, slice thickness=1 mm, FOV=20×20 mm, matrix size=128×64, and NA=2) including a magnetization transfer (MT) module with saturation time (tsat) of 3 s and RF field strengths (B1) of 1μT and 3 μT with offsets swept from −5 ppm to +5 ppm (step= 0.2 ppm). The B0 inhomogeneity maps were acquired using a modified Water Saturation Shift Reference (WASSR) method (34,35) with the same parameters as used for CEST imaging except that TR=1.5 s, tsat =500 ms, B1= 0.5 μT, and offset range of −1 to 1 ppm (0.1 ppm steps). The total acquisition time was 30 min. 1H MR spectra of the volume of interest (2×2×2 mm3) were obtained using a single-voxel STEAM method (stimulated echo acquisition mode spectroscopy) with VAPOR (variable-power radiofrequency pulses with optimized relaxation delays) water suppression and outer volume suppression schemes(36), with parameters as follows: TR =3.0 s, TE =8 ms, a mixing time of 7 ms, and 256 acquisitions (total acquisition time= 12 minutes and 54 seconds). Before each spectroscopic measurement, the shimming of the volume of interest was optimized using the field-map–based automatic shimming implementation method.

Data Processing

Data processing was performed using custom-written scripts in MATLAB (Mathworks, Waltham, MA). Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn manually based on the T2w images. Mean Z-spectra, which display the ratio of the MRI water signal intensity during RF saturation (SΔω) and without saturation (S0) as a function of saturation frequency offset (Δω), were calculated after B0 correction on a per voxel basis, and CEST signals were quantified by MTRasym=(S-Δω – S+Δω)/S0(37). 1H MR spectra were manually phased, baseline corrected and referenced to NAA at 2.0 ppm in Topspin software (version 3, Bruker, Germany). A line-broadening function of 20 Hz was applied prior to Fourier transformation. Spectral peaks were assigned according to the literature(21–23,25,38).

Histology

Hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) and Gram staining were performed as described previously (39,40).

Statistics

All data are shown as mean ± s.d. Student’s t-tests were used for statistical analyses, and differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Endogenous CEST contrast of pathogenic Staphylococcus

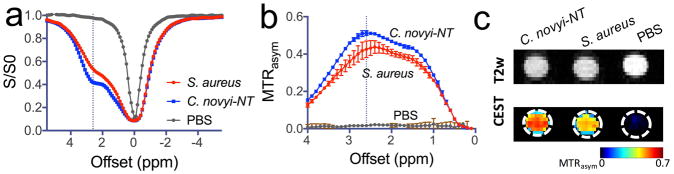

We first performed in vitro studies to confirm the CEST MRI detectability of the pathogenic bacterium S. aureus. As shown in Figure 1, S. aureus (~ 2×108 cells/ml in pH 7.4 PBS solution) exhibited CEST characteristics similar to Clostridium novyi-NT (C. novyi-NT, ~ 2×107 cells/ml in pH 7.4 PBS solution), an anaerobic gram-positive bacterial strain that has been studied previously (30). Despite the slightly different shapes of z-spectra, both bacterial strains showed a strong and broad CEST signal in the range of 1 to 4 ppm, with the maximum CEST MTRasym contrast occurring at a frequency of around 2.6 ppm. Quantitatively, based on the number of cells/ml, S. aureus showed almost 10 times less CEST contrast (MTRasym) than C. novyi-NT. In particular, the CEST contrasts were determined to be 0.2% and 2.6% per million cells for S. aureus and C. novyi-NT, respectively. Furthermore, the CEST MRI signal of S. aureus at different concentrations were measured (Figure S1), confirming the bacCEST MRI signal is dependent on viable bacteria.

Figure 1. CEST MRI detection of Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus).

a) Z-spectra and b) MTRasym plots of S. aureus and Clostridium novyi-NT and PBS; c) MRI images and CEST parametric maps at 2.6 ppm showing the test tubes containing S. aureus, C. novyi-NT and PBS. The concentrations of S. aureus and C. novyi-NT were 2×108 and 2×107 cells/ml in PBS solution (pH 7.4), respectively. All CEST data were acquired using a 3-sec long CW RF pulse (B1=3.6 μT) at 37 °C

Non-invasive detection of brain abscess in vivo using CEST MRI

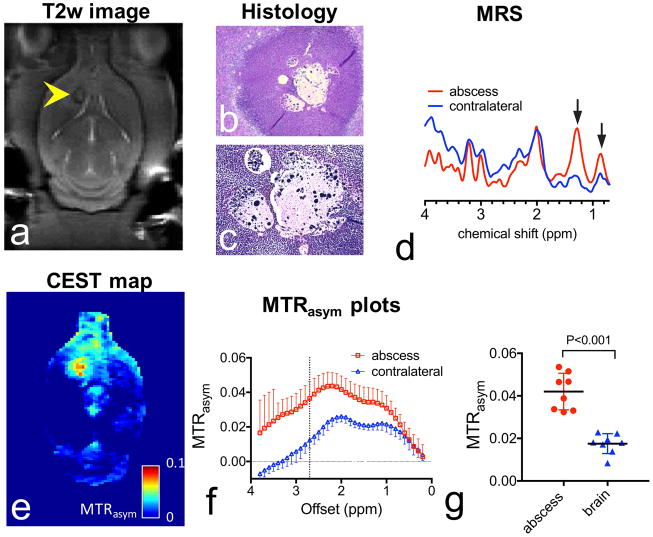

To investigate the CEST MRI detectability of brain abscess in vivo, we performed CEST studies on a rat brain abscess model. The formation of abscesses was confirmed by anatomical T2w MR images (Fig. 2a) at a time point of 12 days after implantation of S. aureus. All lesions appeared either isointense or hypointense at the rim, likely due to the formation of a collagen capsule. The formation of bacterial abscess was further confirmed by H&E staining (Fig. 2b), which shows the formation of capsules surrounded by inflammatory cell infiltration, and the presence of bacterial cells in the center of abscess was revealed by Gram staining (Fig. 2c). Strongly elevated lactate (1.33 ppm) and cytosolic amino acids/lipids (0.9 ppm) were observed on MRS (Fig. 2d), confirming the bacterial infection in these areas(21–23,25,38). The CEST parametric map (MTRasym at 2.6 ppm, Fig. 2e) showed a significantly elevated CEST signal within the area of bacterial infection. Figure 2f shows the corresponding ROI-based analysis for the abscess and contralateral brain. In this rat, the mean MTRasym (2.6 ppm) showed a marked increase from 2.34±0.33 % in the contralateral brain to 3.88±0.87 % in the abscess. A similar effect was observed in all the animals. As shown in Figure 2g, the mean MTRasym(2.6ppm) of brain abscesses (4.20 ± 0.86 %) was significantly higher than that of the contralateral brain (1.75±0.47 %) with a P <0.001 (n=8, Student t test, two-tailed, paired). It should be noted that, as shown in Figure S2, empty agarose beads completely degraded after 9 days and generated no detectable CEST signal.

Figure 2. CEST MRI of brain abscess.

a) T2w image of a representative rat brain with a bacterial abscess on the 12th day after implantation, with the lesion indicated by the yellow arrow. b) H&E stain (4x). c) Gram stain (20x). d) MR spectra of brain abscess (red) and contralateral normal brain tissue (blue) acquired using PRESS (voxel size = 2×2×2 mm3). e) CEST map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=3 μT, tsat = 3s. f) Z-spectra and g) MTRasym plots (mean± sd) of ROIs encompassing the brain abscess (red) and contralateral normal brain tissue (blue). g) Comparison of the CEST contrasts in abscess and contralateral brain (n=8).

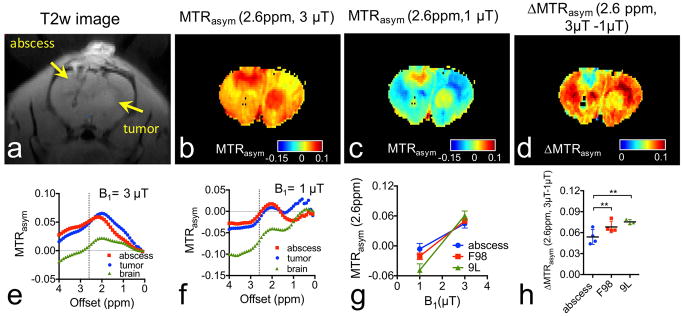

Differentiation of infection and brain tumor by B1-dependent CEST signal

As shown in Figures 3a, conventional T2w imaging is able to delineate brain abscesses and tumors, but unable to discriminate them. It can be seen in Figures 3b–c that both brain abscess and tumor exhibit markedly higher CEST signal than normal brain parenchyma at the B1 values of both 1 μT and 3 μT, in a good agreement with the hyperintense areas in the T2w image. While brain abscess and tumor cannot be differentiated directly using the CEST MRI signal acquired with a single B1 strength, we found that they can be differentiated in a statistically significant manner by their different B1 dependent CEST when acquired using B1 values of 1 μT and 3 μT. For the representative rat shown in Figure 3, the mean MTRasym increased from -0.67% and -1.77% to 5.14% to 4.82% for the brain abscess and tumor respectively (Figs. 3e and f), leading to net MTRasym increases of 5.81% and 6.59 % respectively. To highlight the brain abscess, we calculated the ΔCEST as Δ MTRasym (2.6ppm, 3μT-1μT) =MTRasym(2.6ppm, 3μT) - MTRasym (2.6ppm, 1μT). As shown in figure 3d, after this simple one-step processing, CEST MRI can differentiate brain abscess from tumor. The same effect was observed in multiple animals (Fig. 3g) and generated a significant difference between the groups of brain abscess and brain tumors (Fig. 3h, P=0.005, n=4, Student t test, two-tailed, unpaired). To confirm our approach can be used to separate brain abscess from other type of tumors, we also measured the CEST MRI contrast of rat 9L glioma tumors (Figure S4, Supporting information). As shown in Figs. 3g&h, the same trend can be found in 9L tumors, which has a net Δ MTRasym (2.6ppm, 3μT-1μT) of 7.53% (P=0.0013, n=3, Student t test, two-tailed, unpaired). It should be noted that only two rats were implanted with both tumor cells and S. aureus, while the other four rats were implanted either with tumor cells or S. aureus to generate only one lesion. The purpose of double implantation was to display the CEST contrast in both lesions, while the purpose of single implantation was to avoid the potential impact of one type lesion on the other. Our data shows that the double implantation has negligible effects on CEST contrast as compared to single implantation.

Figure 3. Differentiation of brain abscess from F98 brain tumor using dual-B1 CEST MRI.

a) T2w image showing the bacterial abscess and the tumor as indicated by arrows. b) CEST map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=3 μT. c) MTRasym map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=1 μT. d) ΔCEST map calculated from MTRasym (B1=3 μT) - MTRasym (B1=1 μT). ROI-based MTRasym plots of abscess, tumor and brain using e) B1= 3 μT and f) B1=1 μT. g) B1-dependence of CEST signal of abscesses (n=4), F98 tumors (n=4), and 9L tumors (n=3) at 2.6 ppm offset. h) Bar plots of the mean ΔMTRasym(2.6ppm, 3μT - 1μT) of abscesses (n=4), F98 tumors (n=4), and 9L tumors (n=3).

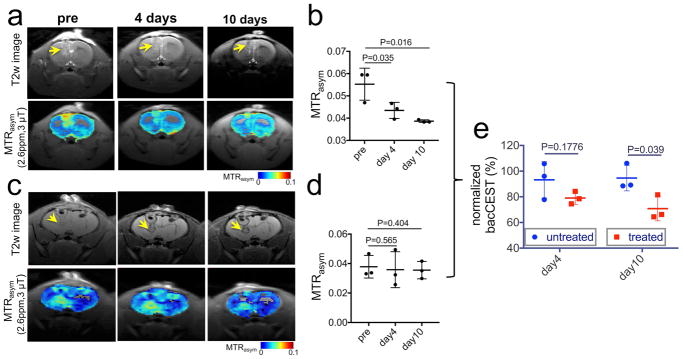

Monitor the response of bacteria to antibiotic treatment

Because the intensity of bacCEST is proportional to cell numbers, it can potentially be used to monitor the inhibition of a treatment on the targeted bacterial cells. To demonstrate it, we performed a longitudinal CEST MRI study on a group of brain abscess-bearing rats (n=3) before and after antibiotic treatment. As reflected by the area of the hyperintense region in T2w images (Fig. 4a), the size of abscess decreased slightly on day 4 (from 20.4 ±4.1% to 16.4±3.8%, P=0.2624), followed by a striking reduction to 12.7 ±1.6% on day 10 (P=0.035). In contrast, the CEST map showed not only a shrinking of hyperintense areas but also a marked decrease in CEST signal in these areas starting on the fourth day after the treatment. For example, using the ROIs drawn based on T2w hyperintense areas, the mean MTRasm (2.6ppm, 3 μT) dropped from 4.69± 0.74% (day 0) to 3.95±0.74% (day 4) and 3.83 ±1.06% (day 10), respectively. As shown in Figure 4b, the statistical analysis clearly showed a significant decrease of CEST signal on day 4 and day 10, i.e., P=0.035 and 0.016 (n=3, Student t test, two-tailed, paired), respectively. In contrast, the CEST MRI of abscesses in animals receiving no treatment remains mostly unchanged (Figure 4c), confirming that the decreased CEST MRI signal in the treatment group is due to the response to treatment. To compare the longitudinal bacCEST signal changes between the treated and untreated groups, the bacCEST signals of each rat at different time points were normalized by its signal on day 0 (before treatment). As shown in Figure 4e, there was a significant difference between the bacCEST signals of treated and untreated animals on day 10 (P=0.039, Student t test, two-tailed, unpaired) but not on day 4 (P=0.1776, Student t test, two-tailed, unpaired). Furthermore, gram stained brain sections from cohorts with and without antibiotic treatment (Figure S4) confirm the absence of any viable bacteria at the end of antibiotic treatment compared to the untreated animals, where abundant viable bacteria were visualized. It should be noted that the quantitative analysis depends highly on the choice of ROI because a clear inhomogeneity was present on all CEST maps.

Figure 4. CEST MRI monitoring the treatment response of bacteria.

a) T2w images showing the location of bacterial abscesses (arrows) and the corresponding CEST maps (overlaid on T2w images) of a representative ampicillin-treated brain-abscess-bearing rat at different time points. b) Scatter plots of mean ROI MTRasym values of abscesses of three rats at different time points after the antibiotic treatment. c) T2w images and CEST maps of a representative untreated brain-abscess-bearing rat at different time points. d) Scatter plots of mean ROI MTRasym values of abscesses of three rats at different time points after the antibiotic treatment. e) Comparison of the bacCEST signal of treated and untreated rats at day 4 and day 10. The bacCEST signals were normalized by the signal on day 0.

Discussion

In the current study, we successfully expanded the principle of bacCEST, an endogenous CEST contrast for detecting the bacterial strain C. novyi-NT (30), to the detection of the pathogenic bacterium S. aureus. Our in vitro results showed that, similar to C. novyi-NT, S. aureus also has a broad CEST contrast over a frequency range from 0.5 ppm to 4 ppm, with the maximum CEST contrast in terms of MTRasym occurring around 2.6 ppm, indicating that bacCEST strategy can potentially be used for detecting different types of bacteria. We consider the apparent endogenous CEST contrast as the sum of CEST signals of all proton-exchangeable components of bacteria, such as cellular carbohydrates, peptides and proteins, and metabolites (30). Thus, the maximum in the MTRasym spectrum is only an apparent maximum and may vary in vivo due to the fact that the magnetization transfer and relaxation properties are significantly different in different tissues (41), which can affect the shape of Z-spectra significantly. It is interesting that S. aureus has a CEST pattern similar to C. novyi-NT, but about 10 times less CEST contrast, tentatively attributed to the difference in the cell shape and biochemical components between these two strains. For example, S. aureus is round-shaped bacterium with the diameter ~ 1 μm (42), while C. novyi is rod-shaped with cell dimensions of 0.5–1.6 by 1.6–18 μm(43), indicating the cell volume of the later could be up to 70 times bigger than the former. The difference in CEST signal may allow the differentiation of different bacterial strains based on the relative CEST signal, which however requires further investigation. Nevertheless, the endogenous bacCEST signals of S. aureus allow the direct detection of its bacterial abscesses formed in the rat brain without the need for any exogenous contrast agents.

Compared to those agent-based molecular imaging approaches, bacCEST is a non-agen-based contrast method, which can greatly improve the applicability in poorly-perfused lesions such as brain abscesses in middle and later stages. The results of this study suggest that bacCEST MRI might be used to differentiate S. aureus abscesses from brain tumors without the need for injecting any imaging agents. While both S. aureus and tumor exhibited strongly elevated CEST contrast, they had different B1-dependent CEST properties, attributed to the difference in the combined effect of their constituent protons with multiple exchange rates. It can be reasoned from our data that pathogens with different overall exchange rates could be differentiated by the same approach. However, such claims would need to be established for individual bacterial and tumor types. In the future, more sophisticated CEST methods (44,45) may be used to improve the ability to differentiate different pathogens based on the differences in their CEST properties including offsets and exchange rates.

Another potential clinical utility of the bacCEST is to monitor the effect of bacterial treatment response. Early detection of the response of brain abscess to an antibiotic treatment is crucial for treatment planning and adjusting. Very often, surgical excision of the abscess foci is immediately required when the antibiotic treatment is ineffective and neurologic deterioration occurs(46). Conventional MRI is unable to directly detect the treatment response, and especially abscesses may enlarge initially when the antibiotic treatment is effective (47). The bacCEST MRI has the potential to provide a new means to monitor the treatment response before any morphological changes can be observed. Our results show that the relative bacCEST contrast decreases significantly after the rats were treated with antibiotics for four days, earlier than the changes observed in T2w image, which didn’t show noticeable morphological changes until day 10. Our study demonstrates that the relative changes in the bacCEST contrast has potential as an imaging biomarker for the inhibition and clearance of bacteria from the infection sites after the administration of treatment in deeply seated organs such as brain, and predicting the therapeutic outcomes. While our study was demonstrated using an 11.7T high-field small animal scanner, the bacCEST contrast at 2.6 ppm is expected to be translatable to clinical MRI scanner (i.e., 3T). It has been recently demonstrated that most metabolites except the amine protons of glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) could be detected at 3T(48). Moreover, it has been shown that CEST technologies can be quickly translated from high-field small animal scanners (e.g., 4.7T, 9.4T or 11.7T) to clinical scanners (i.e., 3T) (49–51), and from rodent models to patients (51,52). Hence, it is expected to have potential for quick translation to the clinic, especially when no imaging agent is required.

Conclusion

In this study, we exploited the endogenous CEST contrast from bacteria cells to non-invasively detect bacterial infection by S. aureus abscesses in the brain and to differentiate them from brain tumors by their different CEST-B1 dependence. Moreover, we demonstrated its potential application in monitoring the responses of bacteria to antibiotic treatments. The present technology doesn’t require the injection of imaging probes, making it highly clinically translatable, especially suitable for monitoring the effectiveness of an antibiotic treatment in deeply seated organs.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. CEST MRI signal of S. aureus at different concentrations using both B1 strengths. a) Z spectra and b) MTRasym plots of S. aureus ( 2×108 cells/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) acquired using B1 of 1.2 and 3.6 μT; c) CEST MRI signal at 2.6 ppm of S. aureus at different concentrations ranging from 2×106 to 2×109 cells/mL in PBS (pH 7.4). CEST MRI was performed on a 9.4 T Bruker vertical bore scanner using a 3-sec long CW RF pulse at 37 °C.

Figure S2. CEST MRI of rat brains implanted with both bacteria and empty agarose beads. a) left: T2w image showing the bacterial abscess and needle track as indicated by arrows, middle: MTRasym map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=1 μT, and right: MTRasym map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=3 μT. b) MTRasym plots (mean± sd) of ROIs encompassing the brain abscess, agarose beads (the area along needle track) and contralateral normal brain tissue. c) Comparison of the mean CEST contrasts of abscess, agarose beads (the area along needle track), and contralateral normal brain tissue (n=3).

Figure S3. CEST MRI of 9L brain tumors. a) T2w image showing the tumor as indicated by the arrow. b) CEST map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=3 μT. c) MTRasym map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=1 μT. d) ΔCEST map calculated from MTRasym (B1=3 μT) - MTRasym (B1=1 μT). ROI-based MTRasym plots of abscess, tumor and brain using e) B1= 3 μT and f) B1=1 μT. g) B1-dependence of CEST signal of tumors and normal brain at 2.6 ppm offset (n=3).

Figure S4. Gram stain of brain abscesses from a representative ampicillin-treated rat (a,c) and a control rat (b, d). No viable bacteria can be found in the abscesses in the treated animal, confirming the effectiveness of the ampicillin treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R03EB021573, R01CA211087, R21CA215860, and R01EB015032.

References

- 1.Brouwer MC, van de Beek D. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of brain abscesses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2017;30(1):129–134. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouwer MC, Tunkel AR, McKhann GM, 2nd, van de Beek D. Brain abscess. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):447–456. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1301635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeshita M, Kagawa M, Izawa M, Takakura K. Current treatment strategies and factors influencing outcome in patients with bacterial brain abscess. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140(12):1263–1270. doi: 10.1007/s007010050248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seydoux C, Francioli P. Bacterial brain abscesses: factors influencing mortality and sequelae. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15(3):394–401. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang SY, Zhao CS. Review of 140 patients with brain abscess. Surg Neurol. 1993;39(4):290–296. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(93)90008-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito N, Aoki K, Sakurai T, Ito K, Hayashi M, Hirata Y, Sato K, Harashina J, Akahata M, Iwabuchi S. Linezolid treatment for intracranial abscesses caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus--two case reports. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2010;50(6):515–517. doi: 10.2176/nmc.50.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mamelak AN, Mampalam TJ, Obana WG, Rosenblum ML. Improved management of multiple brain abscesses: a combined surgical and medical approach. Neurosurgery. 1995;36(1):76–85. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199501000-00010. discussion 85–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdogan C, Hakyemez B, Yildirim N, Parlak M. Brain abscess and cystic brain tumor: discrimination with dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion-weighted MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29(5):663–667. doi: 10.1097/01.rct.0000168868.50256.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gemmel F, Dumarey N, Welling M. Future diagnostic agents. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39(1):11–26. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoerr V, Tuchscherr L, Huve J, Nippe N, Loser K, Glyvuk N, Tsytsyura Y, Holtkamp M, Sunderkotter C, Karst U, Klingauf J, Peters G, Loffler B, Faber C. Bacteria tracking by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Biol. 2013;11:63. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaim AH, Wischer T, O’Reilly T, Jundt G, Frohlich J, von Schulthess GK, Allegrini PR. MR imaging with ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide particles in experimental soft-tissue infections in rats. Radiology. 2002;225(3):808–814. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2253011485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ning X, Lee S, Wang Z, Kim D, Stubblefield B, Gilbert E, Murthy N. Maltodextrin-based imaging probes detect bacteria in vivo with high sensitivity and specificity. Nat Mater. 2011;10(8):602–607. doi: 10.1038/nmat3074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuklin NA, Pancari GD, Tobery TW, Cope L, Jackson J, Gill C, Overbye K, Francis KP, Yu J, Montgomery D, Anderson AS, McClements W, Jansen KU. Real-time monitoring of bacterial infection in vivo: development of bioluminescent staphylococcal foreign-body and deep-thigh-wound mouse infection models. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(9):2740–2748. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2740-2748.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez RJ, Weening EH, Frothingham R, Sempowski GD, Miller VL. Bioluminescence imaging to track bacterial dissemination of Yersinia pestis using different routes of infection in mice. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bleeker-Rovers CP, Vos FJ, Wanten GJ, van der Meer JW, Corstens FH, Kullberg BJ, Oyen WJ. 18F-FDG PET in detecting metastatic infectious disease. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(12):2014–2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang SJ, Lee YJ, Lim S, Kim KI, Lee KC, An GI, Lee TS, Cheon GJ, Lim SM, Kang JH. Imaging of a localized bacterial infection with endogenous thymidine kinase using radioisotope-labeled nucleosides. Int J Med Microbiol. 2012;302(2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kogan F, Hariharan H, Reddy R. Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) Imaging: Description of Technique and Potential Clinical Applications. Curr Radiol Rep. 2013;1(2):102–114. doi: 10.1007/s40134-013-0010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanda T, Fukusato T, Matsuda M, Toyoda K, Oba H, Kotoku J, Haruyama T, Kitajima K, Furui S. Gadolinium-based Contrast Agent Accumulates in the Brain Even in Subjects without Severe Renal Dysfunction: Evaluation of Autopsy Brain Specimens with Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectroscopy. Radiology. 2015;276(1):228–232. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanda T, Matsuda M, Oba H, Toyoda K, Furui S. Gadolinium Deposition after Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging. Radiology. 2015;277(3):924–925. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu X-X, Li B, Yang H-F, Du Y, Li Y, Wang W-X, Zheng H-J, Gong Q-Y. Can diffusion-weighted imaging be used to differentiate brain abscess from other ring-enhancing brain lesions? A meta-analysis. Clinical radiology. 2014;69(9):909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himmelreich U, Accurso R, Malik R, Dolenko B, Somorjai RL, Gupta RK, Gomes L, Mountford CE, Sorrell TC. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus brain abscesses: rat and human studies with 1H MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2005;236(1):261–270. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361040869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai PH, Ho JT, Chen WL, Hsu SS, Wang JS, Pan HB, Yang CF. Brain abscess and necrotic brain tumor: discrimination with proton MR spectroscopy and diffusion-weighted imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(8):1369–1377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dev R, Gupta RK, Poptani H, Roy R, Sharma S, Husain M. Role of in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the diagnosis and management of brain abscesses. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(1):37–42. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199801000-00008. discussion 42–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garg M, Misra MK, Chawla S, Prasad KN, Roy R, Gupta RK. Broad identification of bacterial type from pus by 1H MR spectroscopy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003;33(6):518–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2003.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg M, Gupta RK, Husain M, Chawla S, Chawla J, Kumar R, Rao SB, Misra MK, Prasad KN. Brain abscesses: etiologic categorization with in vivo proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2004;230(2):519–527. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302021317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS. A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST) J Magn Reson. 2000;143(1):79–87. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Zijl PC, Yadav NN. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn’t? Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(4):927–948. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu G, Song X, Chan KW, McMahon MT. Nuts and bolts of chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR in biomedicine. 2013;26(7):810–828. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Zijl P, Sehgal AA. Proton Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) MRS and MRI. eMagRes. 2016;5:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu G, Bettegowda C, Qiao Y, Staedtke V, Chan KW, Bai R, Li Y, Riggins GJ, Kinzler KW, Bulte JW, McMahon MT, Gilad AA, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, van Zijl PC. Noninvasive imaging of infection after treatment with tumor-homing bacteria using Chemical Exchange Saturation Transfer (CEST) MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(6):1690–1698. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brouwer MC, Coutinho JM, van de Beek D. Clinical characteristics and outcome of brain abscess: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82(9):806–813. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staedtke V, Bai RY, Sun W, Huang J, Kibler KK, Tyler BM, Gallia GL, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Zhou S, Riggins GJ. Clostridium novyi-NT can cause regression of orthotopically implanted glioblastomas in rats. Oncotarget. 2015;6(8):5536–5546. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flaris NA, Hickey WF. Development and characterization of an experimental model of brain abscess in the rat. Am J Pathol. 1992;141(6):1299–1307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim M, Gillen J, Landman BA, Zhou J, van Zijl PC. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(6):1441–1450. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu G, Gilad AA, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC, McMahon MT. High-throughput screening of chemical exchange saturation transfer MR contrast agents. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2010;5(3):162–170. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liimatainen T, Hakumaki JM, Kauppinen RA, Ala-Korpela M. Monitoring of gliomas in vivo by diffusion MRI and (1)H MRS during gene therapy-induced apoptosis: interrelationships between water diffusion and mobile lipids. NMR in biomedicine. 2009;22(3):272–279. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu G, Liang Y, Bar-Shir A, Chan KW, Galpoththawela CS, Bernard SM, Tse T, Yadav NN, Walczak P, McMahon MT, Bulte JW, van Zijl PC, Gilad AA. Monitoring enzyme activity using a diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(41):16326–16329. doi: 10.1021/ja204701x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SH, Chang KH, Song IC, Han MH, Kim HC, Kang HS, Han MC. Brain abscess and brain tumor: discrimination with in vivo H-1 MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 1997;204(1):239–245. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bettegowda C, Dang LH, Abrams R, Huso DL, Dillehay L, Cheong I, Agrawal N, Borzillary S, McCaffery JM, Watson EL, Lin KS, Bunz F, Baidoo K, Pomper MG, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Zhou S. Overcoming the hypoxic barrier to radiation therapy with anaerobic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(25):15083–15088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036598100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dang LH, Bettegowda C, Huso DL, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Combination bacteriolytic therapy for the treatment of experimental tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):15155–15160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251543698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanisz GJ, Odrobina EE, Pun J, Escaravage M, Graham SJ, Bronskill MJ, Henkelman RM. T1, T2 relaxation and magnetization transfer in tissue at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(3):507–512. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Touhami A, Jericho MH, Beveridge TJ. Atomic force microscopy of cell growth and division in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(11):3286–3295. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3286-3295.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatheway CL. Toxigenic clostridia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3(1):66–98. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu J, Chan KW, Xu X, Yadav N, Liu G, van Zijl PC. On-resonance variable delay multipulse scheme for imaging of fast-exchanging protons and semisolid macromolecules. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(2):730–739. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zu Z, Xu J, Li H, Chekmenev EY, Quarles CC, Does MD, Gore JC, Gochberg DF. Imaging amide proton transfer and nuclear overhauser enhancement using chemical exchange rotation transfer (CERT) Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(2):471–476. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu CH, Chang WN, Lui CC. Strategies for the management of bacterial brain abscess. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13(10):979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Black P, Graybill JR, Charache P. Penetration of brain abscess by systemically administered antibiotics. J Neurosurg. 1973;38(6):705–709. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.38.6.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JS, Xia D, Jerschow A, Regatte RR. In vitro study of endogenous CEST agents at 3 T and 7 T. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2016;11(1):4–14. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Zijl PC, Jones CK, Ren J, Malloy CR, Sherry AD. MRI detection of glycogen in vivo by using chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging (glycoCEST) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(11):4359–4364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700281104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones CK, Schlosser MJ, van Zijl PC, Pomper MG, Golay X, Zhou J. Amide proton transfer imaging of human brain tumors at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56(3):585–592. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhu H, Jones CK, van Zijl PC, Barker PB, Zhou J. Fast 3D chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging of the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(3):638–644. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wen Z, Hu S, Huang F, Wang X, Guo L, Quan X, Wang S, Zhou J. MR imaging of high-grade brain tumors using endogenous protein and peptide-based contrast. NeuroImage. 2010;51(2):616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dixon WT, Hancu I, Ratnakar SJ, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE, Alsop DC. A multislice gradient echo pulse sequence for CEST imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(1):253–256. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Togao O, Keupp J, Hiwatashi A, Yamashita K, Kikuchi K, Yoneyama M, Honda H. Amide proton transfer imaging of brain tumors using a self-corrected 3D fast spin-echo dixon method: Comparison With separate B0 correction. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(6):2272–2279. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Heo HY, Jiang S, Lee DH, Bottomley PA, Zhou J. Highly accelerated chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) measurements with linear algebraic modeling. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76(1):136–144. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y, Heo HY, Lee DH, Jiang S, Zhao X, Bottomley PA, Zhou J. Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging with fast variably-accelerated sensitivity encoding (vSENSE) Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(6):2225–2238. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heo HY, Zhang Y, Lee DH, Jiang S, Zhao X, Zhou J. Accelerating chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MRI by combining compressed sensing and sensitivity encoding techniques. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(2):779–786. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. CEST MRI signal of S. aureus at different concentrations using both B1 strengths. a) Z spectra and b) MTRasym plots of S. aureus ( 2×108 cells/mL in PBS, pH 7.4) acquired using B1 of 1.2 and 3.6 μT; c) CEST MRI signal at 2.6 ppm of S. aureus at different concentrations ranging from 2×106 to 2×109 cells/mL in PBS (pH 7.4). CEST MRI was performed on a 9.4 T Bruker vertical bore scanner using a 3-sec long CW RF pulse at 37 °C.

Figure S2. CEST MRI of rat brains implanted with both bacteria and empty agarose beads. a) left: T2w image showing the bacterial abscess and needle track as indicated by arrows, middle: MTRasym map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=1 μT, and right: MTRasym map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=3 μT. b) MTRasym plots (mean± sd) of ROIs encompassing the brain abscess, agarose beads (the area along needle track) and contralateral normal brain tissue. c) Comparison of the mean CEST contrasts of abscess, agarose beads (the area along needle track), and contralateral normal brain tissue (n=3).

Figure S3. CEST MRI of 9L brain tumors. a) T2w image showing the tumor as indicated by the arrow. b) CEST map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=3 μT. c) MTRasym map at 2.6 ppm acquired using B1=1 μT. d) ΔCEST map calculated from MTRasym (B1=3 μT) - MTRasym (B1=1 μT). ROI-based MTRasym plots of abscess, tumor and brain using e) B1= 3 μT and f) B1=1 μT. g) B1-dependence of CEST signal of tumors and normal brain at 2.6 ppm offset (n=3).

Figure S4. Gram stain of brain abscesses from a representative ampicillin-treated rat (a,c) and a control rat (b, d). No viable bacteria can be found in the abscesses in the treated animal, confirming the effectiveness of the ampicillin treatment.