Abstract

At the cellular level, circadian timing is maintained by the molecular clock, a family of interacting clock gene transcription factors, nuclear receptors and kinases called clock genes. Daily rhythms in pulmonary function are dictated by the circadian timing system, including rhythmic susceptibility to the harmful effects of air born pollutants, exacerbations in patients with chronic airway disease and the immune-inflammatory response to infection. Further, evidence strongly suggests that the circadian molecular clock has a robust reciprocal interaction with redox signaling and plays a considerable role in the response to oxidative/carbonyl stress. Disruption of the circadian timing system, particularly in airway cells, impairs pulmonary rhythms and lung function, enhances oxidative stress due to airway inhaled pollutants like cigarette smoke and airborne particulate matter and leads to enhanced inflammosenescence, inflammasome activation, DNA damage and fibrosis. Herein, we briefly review recent evidence supporting the role of the lung clock and redox signaling in the lungs, the role of redox signaling in inflammation, oxidative stress and DNA damage responses in lung diseases and their exacerbations. We further describe the potential for clock genes as novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the treatment of chronic lung diseases.

Keywords: Redox signaling, molecular clock, airway disease, chronotherapeutics

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Circadian rhythms are innate biological rhythms with a frequency or period close to 24h. In mammals, circadian rhythms of gene expression, cellular/organismal physiology and behavior are regulated by the Circadian Timing System. At the cellular level, circadian rhythms are driven by an autoregulatory feedback loop oscillator of interacting transcription factors, kinases and nuclear receptors commonly referred to as clock genes [1]. The molecular clock has been described in nearly every mammalian cell and is tightly linked to variations in cellular metabolism, redox signaling and oxidative stress responses [2]. This system includes a central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus that receives and responds to photic cues from the retina and uses an array of neural and neuroendocrine cues to disseminate these timing cues to targets in both the brain and periphery [3]. The SCN synchronizes the activity of downstream central and peripheral clocks in order to maximize the temporal cohesion between variables in the environment (e.g. food availability) and physiology (e.g. insulin release) [4]. The Circadian Timing System makes a substantial contribution to nearly every aspects of mammalian physiology, including pulmonary function have been reviewed recently by us [5, 6]. Herein, we briefly review recent evidence supporting the role of the lung circadian molecular clock and redox signaling in the lungs, the role of the redox system in regulation of inflammation, oxidative stress and DNA damage responses in lung diseases. We further describe the potential for clock genes as novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for the treatment of chronic lung disease.

2. The Mammalian Circadian Clock and its Role in Pulmonary Physiology

It is widely accepted that circadian rhythms in mammals are generated by a cell based and inheritable molecular clock [1]. At its core, the clock is regulated by the heterodimeric BMAL1:CLOCK activator complex at its targets. Though Bmal1 expression oscillates, Clock tends to be stably expressed in most tissues. Though both proteins have DNA binding domains, Clock has innate histone acetyltransferase activity and thus plays the most critical role in transactivation [7]. Through binding and activation at E-box promoter regions, BMAL1:CLOCK regulates the expression of both the period (Per1-3) and cryptochrome (Cry1-2) gene families. Once translated, PER and CRY form heterodimers, are phosphorylated by Casein Kinase and move to the nucleus where they repress their own transcription by blocking the activity of the BMAL1:CLOCK complex (Robinson and Reddy 2014). In addition to PER/CRY, the activator complex also drives the expression on the nuclear receptors REV-ERBα/γ and RORα/γ. REVERB and ROR stabilize the oscillator by regulating the timing and amplitude of Bmal1 expression. Clock proteins are also heavily influenced by posttranslational modifications that affect both their activity and stability [8, 9]. In addition to the primary clock proteins, the molecular oscillator also dictates the timing of tissue and cell specific genes, referred to as clock-controlled genes or CCGs [1]. These tissue/cell specific clock-regulated genetic programs are the hands of the clock, facilitating its temporal program on systems physiology. Thus, disruption of clock gene expression inevitably disturbs the timing and amplitude of these CCGs and the physiological processes which they control and has been implicated in chronic diseases [10, 11].

In healthy individuals, overall lung function exhibits a robust diurnal rhythm, with a daytime peak (12:00 h) and early morning trough (04:00 h). Diurnal variation in peak expiratory flow (PEF), peak expiratory volume (PEV) and respiration (VT and VE) have also been reported and follow the same daily patterns [12, 13]. The well-defined early morning decline in lung function coincides with increased risk of exacerbations among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma [14, 15], suggesting that the lung clock plays a considerable role in the pathophysiology of chronic lung disease [5]. We have also recently reported that lung function varies significantly across the day in mice and that these rhythms are drastically altered by inflammatory mediators and viral infection [16-23] see Fig. 1). As in many tissues, the timing of lung function likely depends on a complex interplay between both SCN-dependent cues and localized molecular clock function in lung cells [3]. Outside of these SCN-driven cues, circadian rhythms of clock gene expression have also been reported in lung tissue [24-26]. Studies suggest that molecular clock in the lung plays a critical role in optimizing the organization of cellular function and responses to environmental stimuli [27, 28]. The timing and amplitude of clock genes and CCG expression in rodent lungs is altered by oxidative stress/redox changes mediated by environmental tobacco smoke, air pollution (airborne particulate matters), hypoxia/hyperoxia, jet-lag/shift work, pro-inflammatory mediators, bacterial endotoxin, bacterial/viral infections and other stressors [16-18, 20-23, 29-36] (Fig. 1). Moreover, substantial evidence suggests that clock disruption, either global or targeted, has a profound influence on pulmonary function and lung pathophysiology, particularly in lung epithelium [5]. The implication being that that disturbance of the clock is not only a critical biomarker of the response to oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators in the lungs, but may contribute to the etiology of disease making targeting of clock function an exciting potential avenue for novel therapeutics.

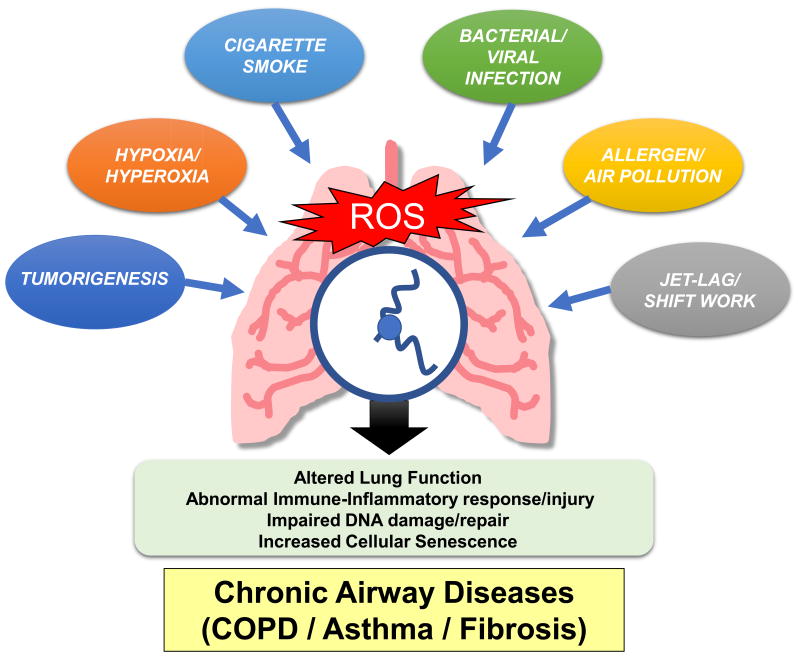

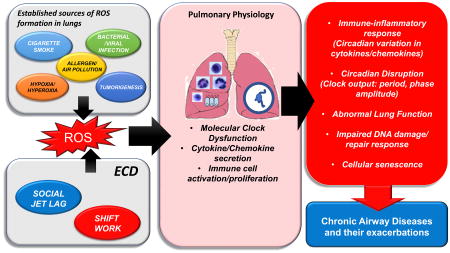

Fig. 1. Factors that contribute to molecular clock dysfunction in the lungs.

The lungs are exposed to different kinds of stressors such as environmental tobacco smoke, bacterial/viral infections, allergens, air pollutants, jet-lag/shift work, etc. that can increase the reactive oxygen species (ROS) burden and thereby alter the rhythmic expression of clock genes. Circadian disruption in the lung affects immune-inflammatory signaling (target genes/canonical pathways) resulting in altered lung function, abnormal inflammatory/immune response, impair DNA damage/repair responses, and ultimately cause chronic lung pathologies (airway disease: COPD, asthma, and fibrosis). Thus, the reciprocal interaction between redox signaling and the clock is a major target of the pulmonary exposome, contributing markedly to the impact of these factors on lung function.

3. Redox regulation of circadian molecular clock

Evidence demonstrates that the circadian clock regulates cellular redox state. For example, Wang et al. demonstrated that the redox state in the SCN in vitro and ex vivo is heavily influenced by the rhythmic expression and activity of two cofactors of cellular metabolism, both flavin adenine nucleotide (FAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) [37]. Moreover, the rhythmic levels of these co-factors in SCN neurons depends on a functional molecular clockwork in rodent SCN [37]. Additional evidence on the oscillations of NAD/NADH in the epidermis of mice [38]; total NAD levels in mouse liver and cultured myoblasts [39] and total NAD(P)H in human erythrocytes [40] demonstrates the ubiquity of the reciprocal interaction between the clock and cellular redox state. NAD+ biosynthesis depends on the synthetic enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt) which is rhythmically expressed under the control of the molecular clock [41]. It has been shown that the level of NAD+ feeds back onto the molecular clock and globally affects the proteome [8]. Additionally, NAD+ oscillation can modulate the activities of NAD-dependent protein modifying enzymes, such as SIRT1 and PARP1 that in turn can deacetylate and poly(ADP-ribosyl) late clock proteins [42, 43]. In another study, using a transient/stable cell line containing REX(x02237)VP16 (REX, a bacterial NADH binding protein, fused to the VP16 activator) and the REX binding operator (ROP), NADH oscillations was demonstrated in vitro. Here, REX was used as a NADH sensor to report intracellular dynamics of redox homeostasis in mammalian cells in real-time [44]. Nuclear FAD levels also oscillate in the liver of mice exposed to a 12:12 L:D cycle, suggesting that this rhythm depends on light input. However, the nuclear level of riboflavin kinase was cycling in the liver even during condition of constant darkness [45]. Intriguingly, Hirano et al., showed that the redox cofactor FAD stabilizes cryptochrome (CRY), modifying clock function [45]. Together, these data suggest that FAD levels oscillate and also feeds back to modulate the activity of the clock.

Peroxiredoxins (PRDXs) make up a phylogenetically ancient family of proteins that potentially evolved in direct response to the Great Oxidation Event and whose primary role is associated with H2O2 detoxification [46]. Peroxiredoxin enzymes work by reducing H2O2 to water. In this catalytic cycle, oxidized PRDX is normally re-reduced in a manner that ultimately consumes a reducing equivalent supplied by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Prior reports have established that the redox state of PRDXs oscillates in cells from humans, mice and algae, reflecting the endogenous rhythm in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)[40, 47-51]. In erythrocytes, these redox rhythms are accompanied by several other metabolic oscillations such as oxidation of hemoglobin, and cycling of NAD(P)H and ATP levels. The rhythmic hyper-oxidation state of PRDXs can be interpreted as a memory of the influx via the catalytic system and would therefore reflect underlying changes in the redox environment on the circadian scale, rather than essentially being a timekeeping mechanism [50]. Consistent with this report, mouse red blood cells from sulfiredoxin mutant mice still display rhythmic PRDX oxidation and daily decline in PRDX hyperoxidation as a result of proteasomal degradation [48]. Importantly, the phylogenetic conservation of PRDX rhythm suggests that circadian redox rhythms may be a common feature observed in all forms of aerobic life [49]. Critically, PRDX redox rhythms persist in mice with mutations that disrupt molecular clock function, indicating that they are not dependent on the clock but may still influence the oscillator to ensure proper responsiveness to environmental stimuli [52].

3.1. Role of Nrf2 in regulation of molecular clock

In addition to the aforementioned interactions, data support the role of pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) as a critical source of the redox cofactor NADPH that in turn regulates redox and transcriptional oscillations via the BMAL1:CLOCK activator complex and the redox-sensitive transcription factor Nrf2. Additionally, they identified Nrf2 and co-activator p300 as two parallel mechanisms that link redox oscillation of BMAL1:CLOCK-mediated transcriptional regulatory programs in nucleated cells [53] (Fig. 2). The impact of the cellular clock as an important regulator of redox homeostasis is supported by studies in clock mutant mouse models (e.g. ClockΔ19, Bmal1 KO) that have increased levels of ROS-associated phenotypes. Clock mutant mice also display altered activity of the antioxidant redox sensitive transcription factor Nrf2 in the lungs associated with reduced glutathione levels, increased protein oxidation and a spontaneous fibrotic phenotype in vivo. This response is seemingly due to the role of BMAL1 as a transcriptional regulator of cellular antioxidant expression via Nrf2 [54, 55]. Clock mutant mice also lack rhythmic expression of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (ahr), suggesting a role for the circadian clock in the regulation of the phase I detoxification signaling pathway [56, 57]. Genome-wide profiling showed inhibin signaling was significantly reduced in CLOCK null mice, establishing the role of circadian clock-inhibin axis in sepsis [58]. BMAL1 KO mice show signs of premature aging and shortened lifespan as a result of increased ROS levels and inflammation in fibroblasts and other tissues, which was partly rescued when animals were continuously administered the reduce glutathione (GSH)-precursor N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) [59, 60]. Together, these studies reveal that BMAL1 can presumably regulate redox-sensitive transcription factors and associated genes (i.e., rhythmic expression of Nrf2 target genes) that play an important role in cellular antioxidant defense.

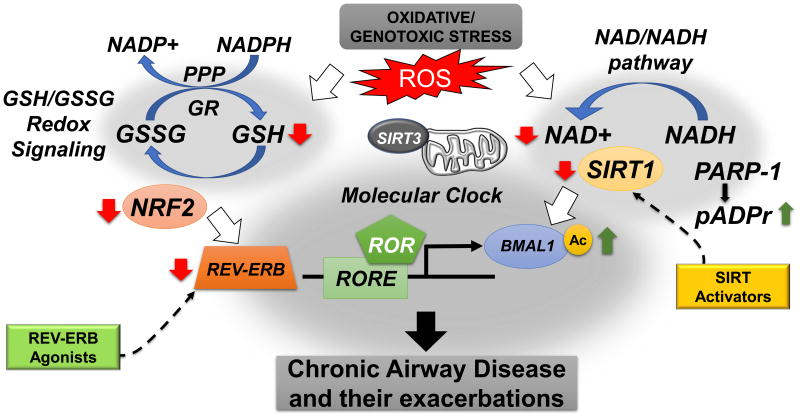

Fig. 2. Crosstalk between circadian clock and redox signaling pathways in the lung.

Oscillation of NAD+ play an important role in modulating the functions of NAD+-dependent enzymes such as SIRT1, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1). These molecules part take in the posttranslational modification of clock proteins (e.g. BMAL1, PER2). Moreover, NAD+ affects mitochondrial metabolism via SIRT3 activation. It has been shown that the level and/or activity of the redox-sensitive transcription factor (NRF2) and other antioxidant enzymes that regulate protection against oxidative stress response oscillate in a rhythmic manner both in vitro and in vivo. This includes glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione reductase (GR), catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxiredoxins (PRXs) (which peaks during the day). Recently, it has been shown that pentose phosphate pathways (PPP), a key pathway in NADPH metabolism, also affects circadian oscillations in a redox-dependent manner. Nrf2 plays a vital role in the interplay between redox and circadian oscillations (in human cells, mouse tissues and flies). The GSH systems is catalyzed by the enzyme GPx which allows reaction of two GSH molecules with H2O2 to form H2O and the oxidized form of GSH, glutathione disulfide (GSSG). The next step in this reaction is catalyzed by GR which requires NADPH as a hydrogen donor that comes from the PPP signaling. Oxidative stress-mediated increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) can directly or indirectly affect both the NAD recovery pathway and GSH/GSSG redox signaling in the lungs. Increased oxidative burden in the lungs (e.g. elevated ROS) can lead to a reduction in SIRT1 and Nrf2, both vital contributors to clock function. Modulating the activity of clock regulators at particular times using novel chronopharmacological agents (e.g. REV-ERB agonists (SR9009, SR9011, GSK4112) and SIRT activators (SRT1720, SRT2183) may attenuate or even reverse molecular clock dysregulation during chronic airway disease such as COPD, asthma and fibrosis.

Another report revealed that deletion of Bmal1 in mice increases neuronal oxidative damage and impairs the expression of several redox defense genes such as aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), indicating that Nrf2-independent oscillations of redox defense genes play an essential role in protection against redox-induced neurodegeneration [61]. There is evidence that circadian oscillation in mitochondrial respiration occur in mouse liver, skin and myotubes. These oscillations coincide with BMAL1-dependent rhythms of mitochondrial biogenesis, protein expression and morphology [38, 39, 62]. Conditional-liver BMAL1 KO mice show reduced and arrhythmic respiration, swollen mitochondria and increases in ROS levels, whereas these phenotypes were partly rescued when the mitochondrial fission 1 protein was overexpressed, suggesting an important role of BMAL1 during regulation of mitochondrial quality control [62]. Another report where they have used these genetically engineered mouse models [63] both at the level of physiologic and genetic (Bmal1/Per2) disruption of circadian rhythms can cooperate with Kras and p53 to promote lung tumorigenesis. This study highlights the importance of cell-autonomous circadian clock control of cellular processes considered hallmarks of cancer that are known to promote cellular transformation and tumor progression [33]. It has been suggested that the appearance of tumors in lung and liver of mice exposed to dichloromethane is linked to altered patterns of clock and clock-controlled gene expression (e.g. Npas2, Anrtl, Nfil3, Dbp, Nr1d1, Nr1d2, Tef, Per3, and Bhehe40) and associated rhythms of metabolism, in a tissue specific manner [64].

3.2. Sirtuins and redox regulation of molecular clock

In addition to the aforementioned pathways, the clock also regulates the levels of NAD production through its influence on the activity of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which is under the transcriptional control of BMAL1:CLOCK complex [41, 65]. Circadian clock-dependent cycles of cellular NAD+ levels can drive mitochondrial oxidative metabolism via sirtuins (i.e. SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT6) and regulate rhythm patterns of oxidative enzyme expression, mitochondrial metabolism and cellular respiration [39, 41, 65, 66]. Thus, several different canonical pathways that depend on the bioavailability of NAD+ as a co-factor play a vital role in modulating both mitochondrial oxidative metabolism (mitochondrial ROS production) and clock function [39, 54, 62, 67]. It has been shown that high fat diet exposure, both during gestation and early post-natal life, reduces Sirtuin levels (Sirt1 and Sirt3), alters cellular redox status (reduced NAD+ levels and NAD/NADH ratio) in concert with altered clock function and activates downstream lipogenic transcription factors (Srebp1c) to developmentally prime the lipogenic pathway [68]. Further, it was reported that PER2 regulates Sirt1 expression during aging. Sirt1-deficient mice show a premature aging phenotype and increased acetylation of histone H4K16 in the Per2 promotor resulting in an open chromatin state leading to increased Per2 transcription; that in turn represses Sirt1 transcription through binding to E-box sites in the Sirt1 promoter [69].

There is a pressing need to develop novel in vivo models of lung inflammatory diseases using clock gene mutant mice (CLOCK, BMAL1, Cry1/2, Per1/2, Rev-Erbα/β KO) and conditional KO mice (lung myeloid or epithelial cell-specific) to better understand their roles in modulating chronic lung pathologies. This is feasibly due to availability of promising genetic and pharmacological tools that are already being tested in different mouse models. Knockout of both REV-ERB isoforms in mouse liver results in compromised expression of circadian clock genes and increased dyslipidemia [70, 71]. REV-ERBα modulates oxidative capacity by regulating mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle [67, 72]. Overall, these studies from clock gene deletion/mutant mice underscore the role of CCGs in linking circadian rhythms, redox regulation to critical cellular processes such as inflammation, mitochondrial metabolism and glucose/lipid homeostasis as they impart their role during pathogenesis of chronic airway diseases.

4. Involvement of molecular clock in redox regulation of inflammation, oxidative stress, DNA damage in relation to lung function/diseases

4.1. Molecular clock and NF-κB

There is a considerable evidence in the literature that show that the severity of immune-inflammatory responses vary across the 24 h day and, conversely, that disruption of the clock has been linked to altered immune responses and inflammatory disease [73, 74]. The novel role of the molecular clock in modulating immune inflammatory signaling pathways, including toll-like receptor 4 and 9, repressing chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and IL-6 expression has been documented [19, 31, 36, 75]. Clock proteins bind to the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (nf-κb) and regulate its transcriptional activity; and CLOCK KO mice showed reduced NF-κB-activation [76]. In a neonatal hyperoxia mouse model, oxidative stress activates REV-ERBα promoter activity through the nf-κb and Nrf2 binding site, thereby regulating redox-mediated oxidative stress and inflammation [35].

4.2. Molecular clock, PARP-1 and DNA damage

Prior studies have shown that both bacterial and viral infections alter the timing and amplitude of clock gene abundance in the lung; likely due to altered expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, bacterial colonization and impaired viral clearance [16, 18-20, 30-32, 34]. Tobacco smoke exposure also causes lung molecular clock disruption as a result of impaired DNA damage/repair signaling associated with carbonyl stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) and a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) as seen in patients with COPD [77-82]. Lungs of patients with COPD show reduced SIRT1 levels/activity and BMAL1 levels associated with clock dysfunction in the lungs [17, 22]. Recent studies clearly demonstrates the role of NAD in modulating circadian clock mediated DNA damage responses through the SIRT1-PARP1 [Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1] axis [83]. This is well supported by data revealing that oxidative stress induced DNA damage responses, utilize NAD+, lead to altered SIRT1 and PARP1 activity. Increased PARP1 activity triggers SIRT1-induced phase advances by decreasing SIRT1 activity in response to reduced NAD+ levels [83]. In a related study, computational modelling was used to suggest that PARP1 reduces SIRT1 activity via competitive binding and sequestration of the critical co-factor NAD+. This competitive inhibition is likely due to protein acetylation in conjunction with phosphorylation that is consistent with earlier report [84]. Previously, we have shown that the SIRT1-PARP1 axis is affected during cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress, leading to increased pro-inflammatory responses, DNA damage, autophagy and cellular senescence [85, 86]. Furthermore, we have shown that oxidants can reduce SIRT1 activity/levels and activate PARP1 independently, though they share the same cofactor NAD+ [87]. It is possible that SIRT1-PARP1 may play an essential role in regulating clock function during chronic inflammatory lung diseases via post-translational modifications. Hence, oxidant-induced clock dysfunction in the lungs may exacerbate prior susceptibility to oxidative DNA damage and cellular senescence during the pathogenesis of chronic airway diseases caused by inhaled toxicants like cigarette smoke.

4.3. Molecular clock disruption, infection and chronic inflammatory disease

The molecular clock clearly drives circadian rhythms of in vivo sensitivity to infectious agents. It has been reported that survival in response to endotoxin (LPS) challenge was reduced in BMAL1 KO mice relative to wild-type littermates [73]. Endotoxin causes circadian clock disruption in macrophages via ROS, thus supporting redox regulation of the molecular clock in inflammatory cells. Peritoneal macrophages isolated from Bmal1 KO and Per1-3 TKO (triple KO) mice displayed altered balance between nitric oxide, and ROS release accompanied by increased uptake of oxidized low density lipids and increased adhesion and migration compared to wild-types [88]. Bmal1 KO mice infected with herpes and influenza virus show increased virus replication, and dissemination, indicating that severity of acute infection is influenced by the clock [89]. The above findings are comparable to previous reports showing that both IAV and hepatitis C virus infection alter the phase and amplitude of clock gene expression [16, 90]. Asthma is a chronic lung inflammatory condition that clearly shows a circadian signature. Asthmatics develop worse symptoms during the night and/or early in the mornings which follows a circadian pattern that correlate with their lung physiology, airway caliber and inflammatory response [12-15]. It has also been shown that human airway cells from 2 independent asthmatic cohorts show considerable downregulation of clock gene expression [18]. Additionally, deletion of the Bmal1 locus exacerbates viral bronchiolitis (extensive asthma-like airway changes, mucus production and increased airway resistance) and increases susceptibility in a Sendai virus (SeV) virus-/influenza virus-induced asthma model that correlates with impaired control of viral replication. These data support a role for Bmal1 in the development of asthmatic airway disease via the regulation of lung antiviral responses [18]. This observation coincides with our study which revealed that influenza A virus (IAV) alters clock function via a Bmal1-dependent pathway [16]. Recently, using an ovalbumin model of allergic asthma in Bmal1 myeloid cell specific (BMAL1-LysM-/-) KO mice, it was demonstrated that there is a significant role for BMAL1 in allergic asthma, as these conditional KO mice show marked increases in lung inflammation, eosinophils, and IL-5 levels. These data suggest that Bmal1 is a potent negative regulator in myeloid cells [21]. Further, it was shown that there is a time-of-day dependent variation in IL-33 mediated IL-6, IL-13 and TNFα production in bone marrow-derived mast cells from wild-type mice that was abolished in Clock mutant mice. Additionally, CLOCK can bind to the promoter region of interleukin 1 receptor-like protein ST2 and Clock deletion leads to down-regulation of ST2 expression in mast cells [91]. Prior studies demonstrate circadian variation in airway leukocytes and eosinophils by using induced sputum, correlating eosinophil activation and levels of circulating inflammatory mediators with airway obstruction and reversibility [92]. Together, this evidence suggests that the molecular clock plays a key role in regulating the activity of various immune-inflammatory cells during asthmatic responses. Thus, molecular clock may modulate the inflammasome pathways or vice-versa leading to persistent immune-inflammatory responses in airway diseases.

4.4. Molecular clock disruption and pro-fibrotic responses (transient to permanent remodeling)

It is now known the role of BMAL1 in the signal transduction and cellular activities of TGF-β1-mediate lung fibrogenesis [93]. TGF-β1 treatment in vitro (lung epithelial cells and fibroblasts) or in vivo using a mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis (adenovirus-TGF-β1-infected mice) leads to upregulation of BMAL1 expression. Knockdown of BMAL1 with siRNA blocked fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation in normal human lung fibroblasts, suggesting BMAL1 is required for TGF-β1-induced signal transduction and pro-fibrotic activities in the lung [93]. In contrast, we have shown that BMAL1 KO mice infected with IAV displayed detriments in behavior, survival, increased lung inflammation and enhanced pro-fibrotic responses [16]. It is possible that viral infection can trigger pro-fibrotic growth factors and their receptors in mouse lung macrophages and fibroblasts, stimulating pro-fibrotic responses in BMAL1 KO mice independent of TGF-β1 induced fibrogenesis [94]. BMAL1 deficient cells (MEFs) demonstrate a greater degree of susceptibility to infection by two major respiratory viruses including Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza virus type 3 (PIV3) that belong to the family Paramyxoviridae, further supporting the role of BMAL1 in cellular viral immunity [34]. Each of these models of lung disease are coincident with, and as suggested above, enhanced by molecular clock dysfunction. Particularly as this influence on the clock relates to changes in cellular redox signaling and metabolism, a response that may underlie the influence of clock dysfunction on the intensity and duration of disease. It remains to be seen whether pharmacological activation of the clock by redox modulating agents using clock-targeting agents constitutes a viable therapeutic approach for treating chronic lung diseases and their exacerbations.

5. Targets and Chronotherapeutics

Mounting experimental evidence suggests that the timing system may be exploited as a novel therapeutic target for multiple conditions, including obesity, malignancy and chronic lung disease. Several potent small molecule effectors of clock function have been identified [95-97] Further, compounds known to affect cellular physiology through redox signaling, such as the SIRT agonists, have also been shown to indirectly affect the clock via intracellular redox changes (Fig. 2 and Table 1). It is likely that advances in our understanding of these compounds and their targets will hasten the use of chronopharmacological compounds for the treatment of pulmonary conditions [98]. A recent study of drugs widely used for the treatment of asthma and COPD (Advair Diskus, Combivent; and ProAir HFA) revealed that their effects may be mediated by changes in CCG expression [99]. Further, this study indicated that more than 50% of all (top-selling) pharmaceutical drugs target clock gene expression and/or their enzymatic activity, with many of these drugs having direct influence in pulmonary physiology (see Table 1). Though promising, there remains a considerable gap in our understanding of clock-dependent physiological functions in the lungs which are affected by intracellular redox changes, the influence of these compounds on the lung clock and the true value of clock-targeting therapeutics for chronic airway disease.

Table 1. Redox Modulating Agents, Molecular Targets and Chronopharmacological Agents for Therapy.

| Molecular Target | Disease Models | Compounds | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| REV-ERBα/β | Influenza, Cigarette smoke, LPS | SR9009, GSK4112 | 16, 17, 105 |

| REV-ERBα | THP-1 cells stimulated with LPS | GSK4112 analog (GSK2945) | 19 |

| BMAL1 | Cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity | Selenium [L-methyl-selenocysteine] | 107 |

| BMAL1 | Xenografted tumor model | Paclitaxel | 108 |

| CLOCK | Bleomycin | Sulforaphane (Nrf2 activator) | 55 |

| SIRT1-BMAL1 | Cigarette smoke, LPS | SRT1720 (Sirt1 Activator) | 17, 22 |

Though several novel clock-related targets have been suggested which are affected by intracellular redox changes, likely candidates include the nuclear receptor REV-ERBα/β, the core clock protein BMAL1 and the Sirtuin (SIRT1, 2) family of deacetylases. Small molecule modulators are available for each and evidence suggests that all three may be targeted for the treatment of chronic airway disease [5]. Several novel compounds that regulate the timing and amplitude of clock gene expression either directly or indirectly via SIRT1 activation have been studied (Table 1). Our lab and others have shown that SIRT1 agonists can improve certain abnormalities seen in COPD and may be protective in a mouse model of emphysema [17, 22].

Treatment with the SIRT1 activator SRT 1720/SRT 2183 altered clock-dependent transcription and decreased H3K9/K14 acetylation [100]. Further, Sirtinol attenuated expression of REV-ERBα and BMAL1 and inhibited LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine release from PBMCs [22]. Finally, the effects of SIRT1 agonist depend on the presence of BMAL1. Experiments in conditional lung epithelium-specific BMAL1 KO reveal that SIRT1 agonists failed to attenuate cigarette smoke induced lung injurious responses [17]. Thus, it is through increased SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of BMAL1, and perhaps PER2, that SIRT1 activator produce their beneficial influence on lung injurious responses to oxidative/carbonyl stress. It is also possible that SIRT1 regulates the activity of other clock components, including the nuclear receptor and repressor, REV-ERBα, which itself stands as a promising target for chronopharmacological treatment of chronic airway disease.

Interestingly, REV-ERB has many hats; acting as a core repressor in the molecular clock, a critical regulator of metabolic/inflammatory gene expression and a metabolic sensor [101]. REV-ERBα/β act as repressors by recruiting HDAC3/NCOR to REV-ERB/ROR response elements in target promotors [102, 103]. REV-ERB has been shown to have both DNA binding dependent and independent repressor activity [103]. As a component of the molecular clock, REV-ERBα binds to ROR response elements (ROREs; see Fig. 2), where it competes with the activator RORα/γ to regulate the timing and amplitude of Bmal1 expression. Small molecules that target REV-ERB have been identified and characterized [101, 104]. These synthetic ligands for REV-ERBα (e.g. GSK4112, SR9011, SR9009) can regulate inflammation, improve respiratory function and normalize sleep/wake rhythm in patients with asthma and COPD [72, 101]. Most-recently, we have shown that treatment with REV-ERBα agonists can attenuate immune/inflammatory markers of cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation both in vitro using small airway epithelial cells/mouse lung fibroblasts and in vivo using mouse models of both acute and sub-chronic smoke exposure [105]. Although promising, none of these compounds have been developed for clinical use and are widely considered useful as experimental compounds for pre-clinical analysis. It is likely that similar compounds, with greater efficacy, reduced dosage requirements and limited adverse effects will be developed to Phase I clinical trials in the near future.

Additional small molecule effectors of oscillator function have been shown to target various components of the core clock, leading to altered timing and amplitude of clock and clock-controlled gene expression (Table 1). These molecules may also have promise as adjunct therapy in conjunction with steroids or (β2–adrenoreceptor agonists [97]. RORα/γ agonists and inverse agonists have been shown to have anti-inflammatory and anti-autoimmune effects, reducing proinflammatory cytokine expression and release, TH17 cell differentiation and auto-antibody production [106]. At present, none of the available ROR agonists or inverse agonists have been examined as putative therapy for chronic lung disease. Finally, it has been reported that selenium, a trace metal found in most commercial rodent diets and many foods, increases BMAL1 levels and activity [107]. Rodents provided a diet high in selenium displayed greater levels of BMAL1 in liver and showed resistance to mortality following exposure to chemotherapeutic drugs [107]. These effects are specific to peripheral oscillators, as selenium did not affect the timing or amplitude of BMAL1 expression in the SCN. Though yet to be developed for clinical trial, these pre-clinical studies strengthen the rationale for the usefulness of chronopharmacological drugs, particularly as add-on therapy in combination with steroids/(β2-adrenoreceptor agonists (standard therapy for chronic airway diseases) for the treatment of inflammation in chronic airway disease where redox changes occur.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

There is now a fairly impressive body of evidence to support a robust reciprocal relationship between redox signalling and molecular clock function (Fig. 2). Circadian rhythms of nicotinamide (NAD) oxidation, Nrf2, glutathione reduction and peroxiredoxin activity have all been reported in mammals. Further, environmental exposomes that increase oxidative stress and produce premature cellular senescence and DNA damage responses in the lungs also result in molecular clock dysfunction. For example, oxidative/carbonyl stress reduces SIRT1 expression in the lungs leading to changes in the acetylation and degradation of the clock protein BMAL1 and PER2. Data suggest that these post-translational modifications can further enhance lung inflammation and cellular senescence. Thus, the timing system may act under normal circumstances as a rheostatic modulator of lung inflammatory and oxidative stress responses that when challenged (as in response to oxidative/carbonyl stress) can also act to increase the amplitude and duration of pro-inflammatory impact on lung function. The influence of oxidative stress on the clock through redox signalling supports the assertion that clock function may be utilized as a novel biomarker of lung pathophysiology. As discussed, studies have linked clock function to nf-κb, TLR4, GSH, NAD/NADH and Nrf2 signalling pathways in lung tissue [2].

The identification of novel clock targeting compounds has paved the way for exiting discoveries in the area of chronopharmacology for chronic lung disease. Clock-targeting compounds may soon be used to normalize/attenuate lung inflammatory and pro-senescence responses and/or enhance the efficacy of glucocorticoids and β2-agonists. The development and application of these drugs in pre-clinical models to reduce lung inflammation, DNA damage and cellular senescence in lung tissue should lead to new and effective clinical therapies. At the same time, these drugs will allow us to probe the detailed and complex mechanisms that define the intersection between clock function, redox signalling and inflammatory/injurious response to exposomes/environmental exposures. It is hopeful that these tools will not only open the door to new basic discoveries, but also provide much needed help for the treatment of debilitating lung diseases and their exacerbations.

Highlights.

Circadian rhythm is regulated by intrinsic molecular clock

Redox regulation of molecular clock (Bmal1, Rev-erbα, Per2) occurs in lung cells

Molecular clock plays a key role in redox regulation of cellular functions

Molecular clock plays a functional role in pulmonary pathophysiology

Molecular Clock can be targeted by chronotherapeutics in lung diseases

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those authors whose excellent contribution in the field could not be cited here because of space limitations.

Funding Sources: This study was supported by the NIH 1R01HL085613, 1R01HL133404, 1R01HL137738 and 1R56ES027012 (to I. Rahman).

Abbreviations

- BMAL1

brain and muscle ARNT-like 1

- CCG

clock-controlled genes

- CLOCK

circadian locomoter output cycles protein kaput

- CRY

Cryptochrome

- KO

knock-out

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized)

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced)

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- Rev-Erbα (Nr1d1)

nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 1

- PER

period

- ROR

Retinoid-Related Orphan Receptor

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SCN

suprachiasmatic nucleus

- SIRT

sirtuin

Footnotes

Akhilesh B. Reddy, David M. Pollock and Martin E. Young

Conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Author contributions: I.K.S. and M.T.S. prepared figures and table; I.K.S., M.T.S., and I.R. drafted this review article; I.K.S., M.T.S., and I.R. edited and revised this review article; I.K.S., M.T.S., and I.R. approved final version of this review article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Robinson I, Reddy AB. Molecular mechanisms of the circadian clockwork in mammals. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(15):2477–83. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Putker M, O'Neill JS. Reciprocal Control of the Circadian Clock and Cellular Redox State - a Critical Appraisal. Mol Cells. 2016;39(1):6–19. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Menaker M, Murphy ZC, Sellix MT. Central control of peripheral circadian oscillators. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23(5):741–6. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mereness AL, Murphy ZC, Forrestel AC, Butler S, Ko C, Richards JS, Sellix MT. Conditional Deletion of Bmal1 in Ovarian Theca Cells Disrupts Ovulation in Female Mice. Endocrinology. 2016;157(2):913–27. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundar IK, Yao H, Sellix MT, Rahman I. Circadian molecular clock in lung pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2015;309(10):L1056–75. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00152.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sundar IK, Yao H, Sellix MT, Rahman I. Circadian clock-coupled lung cellular and molecular functions in chronic airway diseases. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53(3):285–90. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0476TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahar S, Sassone-Corsi P. The epigenetic language of circadian clocks. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;(217):29–44. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-25950-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakahata Y, Kaluzova M, Grimaldi B, Sahar S, Hirayama J, Chen D, Guarente LP, Sassone-Corsi P. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling and circadian control. Cell. 2008;134(2):329–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirayama J, Sahar S, Grimaldi B, Tamaru T, Takamatsu K, Nakahata Y, Sassone-Corsi P. CLOCK-mediated acetylation of BMAL1 controls circadian function. Nature. 2007;450(7172):1086–90. doi: 10.1038/nature06394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans JA, Davidson AJ. Health consequences of circadian disruption in humans and animal models. Progress in molecular biology and translational science. 2013;119:283–323. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396971-2.00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Peek CB, Affinati A, Maury E, Bass J. Circadian clocks and metabolism. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2013;(217):127–55. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-25950-0_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D. Diurnal variability of peak expiratory flow. J Asthma. 2002;39(5):363–73. doi: 10.1081/jas-120004029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchanan GF. Timing, sleep, and respiration in health and disease. Progress in molecular biology and translational science. 2013;119:191–219. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-396971-2.00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skloot GS. Nocturnal asthma: mechanisms and management. Mt Sinai J Med. 2002;69(3):140–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnes PJ. Circadian variation in airway function. Am J Med. 1985;79(6A):5–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundar IK, Ahmad T, Yao H, Hwang JW, Gerloff J, Lawrence BP, Sellix MT, Rahman I. Influenza A virus-dependent remodeling of pulmonary clock function in a mouse model of COPD. Sci Rep. 2015;4:9927. doi: 10.1038/srep09927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang JW, Sundar IK, Yao H, Sellix MT, Rahman I. Circadian clock function is disrupted by environmental tobacco/cigarette smoke, leading to lung inflammation and injury via a SIRT1-BMAL1 pathway. Faseb J. 2014;28(1):176–94. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-232629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehlers A, Xie W, Agapov E, Brown S, Steinberg D, Tidwell R, Sajol G, Schutz R, Weaver R, Yu H, Castro M, Bacharier LB, Wang X, Holtzman MJ, Haspel JA. BMAL1 links the circadian clock to viral airway pathology and asthma phenotypes. Mucosal Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibbs JE, Blaikley J, Beesley S, Matthews L, Simpson KD, Boyce SH, Farrow SN, Else KJ, Singh D, Ray DW, Loudon AS. The nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha mediates circadian regulation of innate immunity through selective regulation of inflammatory cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(2):582–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106750109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbs J, Ince L, Matthews L, Mei J, Bell T, Yang N, Saer B, Begley N, Poolman T, Pariollaud M, Farrow S, DeMayo F, Hussell T, Worthen GS, Ray D, Loudon A. An epithelial circadian clock controls pulmonary inflammation and glucocorticoid action. Nature medicine. 2014;20(8):919–26. doi: 10.1038/nm.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaslona Z, Case S, Early JO, Lalor SJ, McLoughlin RM, Curtis AM, O'Neill LAJ. The circadian protein BMAL1 in myeloid cells is a negative regulator of allergic asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017;312(6):L855–L860. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00072.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao H, Sundar IK, Huang Y, Gerloff J, Sellix MT, Sime PJ, Rahman I. Disruption of Sirtuin 1-Mediated Control of Circadian Molecular Clock and Inflammation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53(6):782–92. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0474OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebel S, Gerstmayer B, Kuhl P, Borlak J, Meurrens K, Muller T. The kinetics of transcriptomic changes induced by cigarette smoke in rat lungs reveals a specific program of defense, inflammation, and circadian clock gene expression. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2006;93(2):422–31. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbs JE, Beesley S, Plumb J, Singh D, Farrow S, Ray DW, Loudon AS. Circadian timing in the lung; a specific role for bronchiolar epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):268–76. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oishi K, Sakamoto K, Okada T, Nagase T, Ishida N. Antiphase circadian expression between BMAL1 and period homologue mRNA in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and peripheral tissues of rats. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1998;253(2):199–203. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oishi K, Sakamoto K, Okada T, Nagase T, Ishida N. Humoral signals mediate the circadian expression of rat period homologue (rPer2) mRNA in peripheral tissues. Neuroscience letters. 1998;256(2):117–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00765-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levi F, Schibler U. Circadian rhythms: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:593–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly DF, Westgate EJ, FitzGerald GA. Peripheral circadian clocks in the vasculature. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(8):1694–705. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.144923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavadini G, Petrzilka S, Kohler P, Jud C, Tobler I, Birchler T, Fontana A. TNF-alpha suppresses the expression of clock genes by interfering with E-box-mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(31):12843–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701466104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haspel JA, Chettimada S, Shaik RS, Chu JH, Raby BA, Cernadas M, Carey V, Process V, Hunninghake GM, Ifedigbo E, Lederer JA, Englert J, Pelton A, Coronata A, Fredenburgh LE, Choi AM. Circadian rhythm reprogramming during lung inflammation. Nature communications. 2014;5:4753. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller M, Mazuch J, Abraham U, Eom GD, Herzog ED, Volk HD, Kramer A, Maier B. A circadian clock in macrophages controls inflammatory immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(50):21407–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906361106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen KD, Fentress SJ, Qiu Y, Yun K, Cox JS, Chawla A. Circadian gene Bmal1 regulates diurnal oscillations of Ly6C(hi) inflammatory monocytes. Science. 2013;341(6153):1483–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1240636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papagiannakopoulos T, Bauer MR, Davidson SM, Heimann M, Subbaraj L, Bhutkar A, Bartlebaugh J, Vander Heiden MG, Jacks T. Circadian Rhythm Disruption Promotes Lung Tumorigenesis. Cell Metab. 2016;24(2):324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majumdar T, Dhar J, Patel S, Kondratov R, Barik S. Circadian transcription factor BMAL1 regulates innate immunity against select RNA viruses. Innate Immun. 2017;23(2):147–154. doi: 10.1177/1753425916681075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang G, Wright CJ, Hinson MD, Fernando AP, Sengupta S, Biswas C, La P, Dennery PA. Oxidative stress and inflammation modulate Rev-erbalpha signaling in the neonatal lung and affect circadian rhythmicity. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2014;21(1):17–32. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato S, Sakurai T, Ogasawara J, Takahashi M, Izawa T, Imaizumi K, Taniguchi N, Ohno H, Kizaki T. A Circadian Clock Gene, Rev-erbalpha, Modulates the Inflammatory Function of Macrophages through the Negative Regulation of Ccl2 Expression. J Immunol. 2014;192(1):407–17. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang TA, Yu YV, Govindaiah G, Ye X, Artinian L, Coleman TP, Sweedler JV, Cox CL, Gillette MU. Circadian rhythm of redox state regulates excitability in suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Science. 2012;337(6096):839–42. doi: 10.1126/science.1222826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stringari C, Wang H, Geyfman M, Crosignani V, Kumar V, Takahashi JS, Andersen B, Gratton E. In vivo single-cell detection of metabolic oscillations in stem cells. Cell Rep. 2015;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peek CB, Affinati AH, Ramsey KM, Kuo HY, Yu W, Sena LA, Ilkayeva O, Marcheva B, Kobayashi Y, Omura C, Levine DC, Bacsik DJ, Gius D, Newgard CB, Goetzman E, Chandel NS, Denu JM, Mrksich M, Bass J. Circadian clock NAD+ cycle drives mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in mice. Science. 2013;342(6158):1243417. doi: 10.1126/science.1243417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Neill JS, Reddy AB. Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature. 2011;469(7331):498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature09702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramsey KM, Yoshino J, Brace CS, Abrassart D, Kobayashi Y, Marcheva B, Hong HK, Chong JL, Buhr ED, Lee C, Takahashi JS, Imai S, Bass J. Circadian clock feedback cycle through NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis. Science. 2009;324(5927):651–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1171641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, Reinke H, Dibner C, Kreppel F, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Schibler U. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell. 2008;134(2):317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asher G, Reinke H, Altmeyer M, Gutierrez-Arcelus M, Hottiger MO, Schibler U. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 participates in the phase entrainment of circadian clocks to feeding. Cell. 2010;142(6):943–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang G, Zhang Y, Shan Y, Yang S, Chelliah Y, Wang H, Takahashi JS. Circadian Oscillations of NADH Redox State Using a Heterologous Metabolic Sensor in Mammalian Cells. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(46):23906–23914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.728774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirano A, Braas D, Fu YH, Ptacek LJ. FAD Regulates CRYPTOCHROME Protein Stability and Circadian Clock in Mice. Cell Rep. 2017;19(2):255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loudon AS. Circadian biology: a 2.5 billion year old clock. Curr Biol. 2012;22(14):R570–1. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Causton HC, Feeney KA, Ziegler CA, O'Neill JS. Metabolic Cycles in Yeast Share Features Conserved among Circadian Rhythms. Curr Biol. 2015;25(8):1056–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho CS, Yoon HJ, Kim JY, Woo HA, Rhee SG. Circadian rhythm of hyperoxidized peroxiredoxin II is determined by hemoglobin autoxidation and the 20S proteasome in red blood cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(33):12043–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edgar RS, Green EW, Zhao Y, van Ooijen G, Olmedo M, Qin X, Xu Y, Pan M, Valekunja UK, Feeney KA, Maywood ES, Hastings MH, Baliga NS, Merrow M, Millar AJ, Johnson CH, Kyriacou CP, O'Neill JS, Reddy AB. Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms. Nature. 2012;485(7399):459–64. doi: 10.1038/nature11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoyle NP, O'Neill JS. Oxidation-reduction cycles of peroxiredoxin proteins and nontranscriptional aspects of timekeeping. Biochemistry. 2015;54(2):184–93. doi: 10.1021/bi5008386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Neill JS, van Ooijen G, Dixon LE, Troein C, Corellou F, Bouget FY, Reddy AB, Millar AJ. Circadian rhythms persist without transcription in a eukaryote. Nature. 2011;469(7331):554–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou M, Wang W, Karapetyan S, Mwimba M, Marques J, Buchler NE, Dong X. Redox rhythm reinforces the circadian clock to gate immune response. Nature. 2015;523(7561):472–6. doi: 10.1038/nature14449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rey G, Valekunja UK, Feeney KA, Wulund L, Milev NB, Stangherlin A, Ansel-Bollepalli L, Velagapudi V, O'Neill JS, Reddy AB. The Pentose Phosphate Pathway Regulates the Circadian Clock. Cell Metab. 2016;24(3):462–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J, Moulik M, Fang Z, Saha P, Zou F, Xu Y, Nelson DL, Ma K, Moore DD, Yechoor VK. Bmal1 and beta-cell clock are required for adaptation to circadian disruption, and their loss of function leads to oxidative stress-induced beta-cell failure in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(11):2327–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01421-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pekovic-Vaughan V, Gibbs J, Yoshitane H, Yang N, Pathiranage D, Guo B, Sagami A, Taguchi K, Bechtold D, Loudon A, Yamamoto M, Chan J, van der Horst GT, Fukada Y, Meng QJ. The circadian clock regulates rhythmic activation of the NRF2/glutathione-mediated antioxidant defense pathway to modulate pulmonary fibrosis. Genes & development. 2014;28(6):548–60. doi: 10.1101/gad.237081.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richardson VM, Santostefano MJ, Birnbaum LS. Daily cycle of bHLH-PAS proteins, Ah receptor and Arnt, in multiple tissues of female Sprague-Dawley rats. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1998;252(1):225–31. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanimura N, Kusunose N, Matsunaga N, Koyanagi S, Ohdo S. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated Cyp1a1 expression is modulated in a CLOCK-dependent circadian manner. Toxicology. 2011;290(2-3):203–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang CY, Hsieh MJ, Hsieh IC, Shie SS, Ho MY, Yeh JK, Tsai ML, Yang CH, Hung KC, Wang CC, Wen MS. CLOCK modulates survival and acute lung injury in mice with polymicrobial sepsis. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2016;478(2):935–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kondratov RV, Kondratova AA, Gorbacheva VY, Vykhovanets OV, Antoch MP. Early aging and age-related pathologies in mice deficient in BMAL1, the core componentof the circadian clock. Genes & development. 2006;20(14):1868–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1432206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kondratov RV, Vykhovanets O, Kondratova AA, Antoch MP. Antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine ameliorates symptoms of premature aging associated with the deficiency of the circadian protein BMAL1. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1(12):979–87. doi: 10.18632/aging.100113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Musiek ES, Lim MM, Yang G, Bauer AQ, Qi L, Lee Y, Roh JH, Ortiz-Gonzalez X, Dearborn JT, Culver JP, Herzog ED, Hogenesch JB, Wozniak DF, Dikranian K, Giasson BI, Weaver DR, Holtzman DM, Fitzgerald GA. Circadian clock proteins regulate neuronal redox homeostasis and neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5389–400. doi: 10.1172/JCI70317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobi D, Liu S, Burkewitz K, Kory N, Knudsen NH, Alexander RK, Unluturk U, Li X, Kong X, Hyde AL, Gangl MR, Mair WB, Lee CH. Hepatic Bmal1 Regulates Rhythmic Mitochondrial Dynamics and Promotes Metabolic Fitness. Cell Metab. 2015;22(4):709–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson EL, Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Bronson R, Crowley D, Brown M, Jacks T. The differential effects of mutant p53 alleles on advanced murine lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(22):10280–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Andersen ME, Black MB, Campbell JL, Pendse SN, Clewell HJ, Iii, Pottenger LH, Bus JS, Dodd DE, Kemp DC, McMullen PD. Combining transcriptomics and PBPK modeling indicates a primary role of hypoxia and altered circadian signaling in dichloromethane carcinogenicity in mouse lung and liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Astarita G, Kaluzova M, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1. Science. 2009;324(5927):654–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1170803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Masri S, Rigor P, Cervantes M, Ceglia N, Sebastian C, Xiao C, Roqueta-Rivera M, Deng C, Osborne TF, Mostoslavsky R, Baldi P, Sassone-Corsi P. Partitioning circadian transcription by SIRT6 leads to segregated control of cellular metabolism. Cell. 2014;158(3):659–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Woldt E, Sebti Y, Solt LA, Duhem C, Lancel S, Eeckhoute J, Hesselink MK, Paquet C, Delhaye S, Shin Y, Kamenecka TM, Schaart G, Lefebvre P, Neviere R, Burris TP, Schrauwen P, Staels B, Duez H. Rev-erb-alpha modulates skeletal muscle oxidative capacity by regulating mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy. Nature medicine. 2013;19(8):1039–46. doi: 10.1038/nm.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bruce KD, Szczepankiewicz D, Sihota KK, Ravindraanandan M, Thomas H, Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC, Hanson MA, Byrne CD, Cagampang FR. Altered cellular redox status, sirtuin abundance and clock gene expression in a mouse model of developmentally primed NASH. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861(7):584–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2016.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang RH, Zhao T, Cui K, Hu G, Chen Q, Chen W, Wang XW, Soto-Gutierrez A, Zhao K, Deng CX. Negative reciprocal regulation between Sirt1 and Per2 modulates the circadian clock and aging. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28633. doi: 10.1038/srep28633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cho H, Zhao X, Hatori M, Yu RT, Barish GD, Lam MT, Chong LW, DiTacchio L, Atkins AR, Glass CK, Liddle C, Auwerx J, Downes M, Panda S, Evans RM. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-alpha and REV-ERB-beta. Nature. 2012;485(7396):123–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bugge A, Feng D, Everett LJ, Briggs ER, Mullican SE, Wang F, Jager J, Lazar MA. Rev-erbalpha and Rev-erbbeta coordinately protect the circadian clock and normal metabolic function. Genes & development. 2012;26(7):657–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.186858.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Solt LA, Wang Y, Banerjee S, Hughes T, Kojetin DJ, Lundasen T, Shin Y, Liu J, Cameron MD, Noel R, Yoo SH, Takahashi JS, Butler AA, Kamenecka TM, Burris TP. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by synthetic REV-ERB agonists. Nature. 2012;485(7396):62–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Curtis AM, Fagundes CT, Yang G, Palsson-McDermott EM, Wochal P, McGettrick AF, Foley NH, Early JO, Chen L, Zhang H, Xue C, Geiger SS, Hokamp K, Reilly MP, Coogan AN, Vigorito E, FitzGerald GA, O'Neill LA. Circadian control of innate immunity in macrophages by miR-155 targeting Bmal1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(23):7231–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501327112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cermakian N, Lange T, Golombek D, Sarkar D, Nakao A, Shibata S, Mazzoccoli G. Crosstalk between the circadian clock circuitry and the immune system. Chronobiology international. 2013;30(7):870–88. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2013.782315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Silver AC, Arjona A, Walker WE, Fikrig E. The circadian clock controls toll-like receptor 9-mediated innate and adaptive immunity. Immunity. 2012;36(2):251–61. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spengler ML, Kuropatwinski KK, Comas M, Gasparian AV, Fedtsova N, Gleiberman AS, Gitlin II, Artemicheva NM, Deluca KA, Gudkov AV, Antoch MP. Core circadian protein CLOCK is a positive regulator of NF-kappaB-mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(37):E2457–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206274109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tuder RM, Kern JA, Miller YE. Senescence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9(2):62–3. doi: 10.1513/pats.201201-012MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salminen A, Kauppinen A, Kaarniranta K. Emerging role of NF-kappaB signaling in the induction of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) Cell Signal. 2012;24(4):835–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aoshiba K, Zhou F, Tsuji T, Nagai A. DNA damage as a molecular link in the pathogenesis of COPD in smokers. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(6):1368–76. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00050211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rodier F, Munoz DP, Teachenor R, Chu V, Le O, Bhaumik D, Coppe JP, Campeau E, Beausejour CM, Kim SH, Davalos AR, Campisi J. DNA-SCARS: distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 1):68–81. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WA, Munoz DP, Raza SR, Freund A, Campeau E, Davalos AR, Campisi J. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(8):973–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu ZH, Shi Y, Tibbetts RS, Miyamoto S. Molecular linkage between the kinase ATM and NF-kappaB signaling in response to genotoxic stimuli. Science. 2006;311(5764):1141–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1121513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luna A, Aladjem MI, Kohn KW. SIRT1/PARP1 crosstalk: connecting DNA damage and metabolism. Genome Integr. 2013;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/2041-9414-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luna A, McFadden GB, Aladjem MI, Kohn KW. Predicted Role of NAD Utilization in the Control of Circadian Rhythms during DNA Damage Response. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11(5):e1004144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yao H, Sundar IK, Gorbunova V, Rahman I. P21-PARP-1 pathway is involved in cigarette smoke-induced lung DNA damage and cellular senescence. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hwang JW, Chung S, Sundar IK, Yao H, Arunachalam G, McBurney MW, Rahman I. Cigarette smoke-induced autophagy is regulated by SIRT1-PARP-1-dependent mechanism: implication in pathogenesis of COPD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;500(2):203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Caito S, Hwang JW, Chung S, Yao H, Sundar IK, Rahman I. PARP-1 inhibition does not restore oxidant-mediated reduction in SIRT1 activity. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2010;392(3):264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.12.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang Y, Pati P, Xu Y, Chen F, Stepp DW, Huo Y, Rudic RD, Fulton DJ. Endotoxin Disrupts Circadian Rhythms in Macrophages via Reactive Oxygen Species. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Edgar RS, Stangherlin A, Nagy AD, Nicoll MP, Efstathiou S, O'Neill JS, Reddy AB. Cell autonomous regulation of herpes and influenza virus infection by the circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(36):10085–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601895113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Benegiamo G, Mazzoccoli G, Cappello F, Rappa F, Scibetta N, Oben J, Greco A, Williams R, Andriulli A, Vinciguerra M, Pazienza V. Mutual antagonism between circadian protein period 2 and hepatitis C virus replication in hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kawauchi T, Ishimaru K, Nakamura Y, Nakano N, Hara M, Ogawa H, Okumura K, Shibata S, Nakao A. Clock-dependent temporal regulation of IL-33/ST2-mediated mast cell response. Allergol Int. 2017;66(3):472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.alit.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Panzer SE, Dodge AM, Kelly EA, Jarjour NN. Circadian variation of sputum inflammatory cells in mild asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(2):308–12. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dong C, Gongora R, Sosulski ML, Luo F, Sanchez CG. Regulation of transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-beta1)-induced pro-fibrotic activities by circadian clock gene BMAL1. Respir Res. 2016;17:4. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0320-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Anikina AG, Shkurupii VA, Potapova OV, Kovner AV, Shestopalov AM. Expression of profibrotic growth factors and their receptors by mouse lung macrophages and fibroblasts under conditions of acute viral inflammation in influenza A/H5N1 virus. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2014;156(6):833–7. doi: 10.1007/s10517-014-2463-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen Z, Yoo SH, Park YS, Kim KH, Wei S, Buhr E, Ye ZY, Pan HL, Takahashi JS. Identification of diverse modulators of central and peripheral circadian clocks by high-throughput chemical screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(1):101–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118034108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.He B, Chen Z. Molecular Targets for Small-Molecule Modulators of Circadian Clocks. Curr Drug Metab. 2016;17(5):503–12. doi: 10.2174/1389200217666160111124439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen Z, Yoo SH, Takahashi JS. Small molecule modifiers of circadian clocks. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2013;70(16):2985–98. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1207-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kathale ND, Liu AC. Prevalence of cycling genes and drug targets calls for prospective chronotherapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(45):15869–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418570111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang R, Lahens NF, Ballance HI, Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB. A circadian gene expression atlas in mammals: implications for biology and medicine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(45):16219–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408886111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bellet MM, Nakahata Y, Boudjelal M, Watts E, Mossakowska DE, Edwards KA, Cervantes M, Astarita G, Loh C, Ellis JL, Vlasuk GP, Sassone-Corsi P. Pharmacological modulation of circadian rhythms by synthetic activators of the deacetylase SIRT1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(9):3333–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214266110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kojetin DJ, Burris TP. REV-ERB and ROR nuclear receptors as drug targets. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2014;13(3):197–216. doi: 10.1038/nrd4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang Y, Fang B, Emmett MJ, Damle M, Sun Z, Feng D, Armour SM, Remsberg JR, Jager J, Soccio RE, Steger DJ, Lazar MA. GENE REGULATION. Discrete functions of nuclear receptor Rev-erbalpha couple metabolism to the clock. Science. 2015;348(6242):1488–92. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Butler AA, Burris TP. Segregation of Clock and Non-Clock Regulatory Functions of REV-ERB. Cell Metab. 2015;22(2):197–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sitaula S, Billon C, Kamenecka TM, Solt LA, Burris TP. Suppression of atherosclerosis by synthetic REV-ERB agonist. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2015;460(3):566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.03.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sundar IK, Rashid K, Sellix MT, Rahman I. The nuclear receptor and clock gene REV-ERBalpha regulates cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.157. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Solt LA, Banerjee S, Campbell S, Kamenecka TM, Burris TP. ROR inverse agonist suppresses insulitis and prevents hyperglycemia in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinology. 2015;156(3):869–81. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hu Y, Spengler ML, Kuropatwinski KK, Comas-Soberats M, Jackson M, Chernov MV, Gleiberman AS, Fedtsova N, Rustum YM, Gudkov AV, Antoch MP. Selenium is a modulator of circadian clock that protects mice from the toxicity of a chemotherapeutic drug via upregulation of the core clock protein. BMAL1, Oncotarget. 2011;2(12):1279–90. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tang Q, Cheng B, Xie M, Chen Y, Zhao J, Zhou X, Chen L. Circadian Clock Gene Bmal1 Inhibits Tumorigenesis and Increases Paclitaxel Sensitivity in Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77(2):532–544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]