Abstract

Background

Potentially preventable admissions are a target for healthcare cost containment.

Objective

To identify rates of, characterize associations with, and explore physician decision-making around potentially preventable admissions.

Design

A comparative cohort study was used to determine rates of potentially preventable admissions and to identify associated factors and patient outcomes. A qualitative case study was used to explore physicians’ clinical decision-making.

Participants

Patients admitted from the emergency department (ED) to the general medicine (GM) service over a total of 4 weeks were included as cases (N = 401). Physicians from both emergency medicine (EM) and GM that were involved in the cases were included (N = 82).

Approach

Physicians categorized admissions as potentially preventable. We examined differences in patient characteristics, admission characteristics, and patient outcomes between potentially preventable and control admissions. Interviews with participating physicians were conducted and transcribed. Transcriptions were systematically analyzed for key concepts regarding potentially preventable admissions.

Key Results

EM and GM physicians categorized 22.2% (90/401) of admissions as potentially preventable. There were no significant differences between potentially preventable and control admissions in patient or admission characteristics. Potentially preventable admissions had shorter length of stay (2.1 vs. 3.6 days, p < 0.001). There was no difference in other patient outcomes. Physicians discussed several provider, system, and patient factors that affected clinical decision-making around potentially preventable admissions, particularly in the “gray zone,” including risk of deterioration at home, the risk of hospitalization, the cost to the patient, and the presence of outpatient resources. Differences in provider training, risk assessment, and provider understanding of outpatient access accounted for differences in decisions between EM and GM physicians.

Conclusions

Collaboration between EM and GM physicians around patients in the gray zone, focusing on patient risk, cost, and outpatient resources, may provide an avenues for reducing potentially preventable admissions and lowering healthcare spending.

KEY WORDS: potentially preventable admissions, avoidable admissions, medical decision-making, risk assessment, health care costs

INTRODUCTION

National healthcare expenditures in the United States now total $3.0 trillion annually, with 32% spent on inpatient hospital care.1 While total hospitalizations decreased by 1.2% from 2008 to 2012, hospital admissions from the emergency department (ED) increased by 5%.2–4 Given the cost of hospitalizations, potentially preventable admissions are a focus for healthcare cost containment and a marker of healthcare quality.3–5 Potentially preventable admissions are defined as conditions that can be managed with timely and effective treatment in the outpatient setting.6 Previous studies have been unable to identify objective factors associated with potentially preventable admissions, including age, sex, functional status, comorbidities, access to outpatient care, and time of arrival to the ED.6–14 Evidence suggests that physicians are better able to identify potentially preventable admissions than are objective measures and prediction tools.9, 15–19

Despite this evidence, however, physicians’ decisions regarding hospitalization are still unpredictable.8, 20–23 Disagreement between physicians about the need for hospital admission has been reported in one in five cases.22–24 Physicians’ decisions regarding admissions vary based on tolerance of risk, level of experience, and clinical gestalt.25, 26 To date, no studies of clinical decision-making have investigated decisions around potentially preventable admissions from the ED.8, 14 By understanding the decision-making process for hospital admission from the ED, we may better understand factors associated with potentially preventable admissions.23, 27, 28

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to investigate physician perspectives and decision-making regarding potentially preventable admissions. To achieve this goal, we sought to 1) determine the rates of potentially preventable admissions at our institution, 2) identify factors and patient outcomes associated with potentially preventable admissions, and 3) explore physicians’ clinical decision-making regarding potentially preventable admissions.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

This study was performed at an academic tertiary care hospital in Rochester, MN. The ED has approximately 80,000 patient visits a year, with 75 beds, including an observational unit. The hospital has 1265 beds and 11 general medicine (GM) hospital services that account for 6500 hospital admissions each year. The ED is staffed by emergency medicine (EM) physicians and residents. EM physician have admission privileges and discuss potential admissions with the medical officer of the day. Adult patients are then triaged to a GM hospital service, which includes internal medicine and family medicine. We evaluated all admissions of patients admitted to the GM services during a 14-day period in June 2014 and an additional 14-day period in November 2014. Two separate time periods were used to include a larger sampling of providers in both the EM and GM departments.

Quantitative Analysis

We performed a comparative cohort study to investigate rates of potentially preventable admissions and to examine for associated factors. Given that physician decisions about potentially preventable admissions have been demonstrated to be better than prediction tools,9, 15–19 we defined cases of potentially preventable admissions through a physician survey. Within 24 h of a hospital admission, the admitting EM and GM physicians were asked whether they believed that the hospital admission was potentially preventable. If at least one physician determined that it was, this admission was considered a potentially preventable admission. Controls comprised all other admissions during the same time period.

To identify factors associated with potentially preventable admissions, we extracted patient data from the electronic medical record using Advanced Cohort Explorer, an advanced query tool that allows authorized users to access clinical and administrative data from multiple clinical and hospital source systems within Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. Based on reported associations from previous studies, we extracted data on age, sex, race, insurance, location of residence, admission level of care, primary care provider location, comorbid conditions (Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI]), functional status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] performance status), ED arrival time, ED arrival day, hospital admission time, and hospital admission day.13, 14, 25, 29–31 Data were manually reviewed by the primary author (LD) to calculate the CCI and ECOG performance status scores. To assess patient outcomes, we extracted data on ED length of stay, hospital length of stay, discharge level of care, 30-day revisit to the ED, 30-day readmission, and in-hospital mortality. To compare these variables between potentially preventable and control admissions, we used a chi-square test of association for categorical variables and two-sided t tests for continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.4 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). To compensate for multiple comparisons, we used a Bonferroni correction and set a p value of <0.003 as statistically significant.

Qualitative Case Study

We used a case study methodology to explore physicians’ decision-making processes regarding patient admission in cases of disagreement. Using a single case study methodology with multiple embedded units in order to compare perspectives on the specific case of interest, potentially preventable admissions,32, 33 we evaluated the clinical decision-making process at the time of hospital admission for both the EM and GM physicians.

Sampling Strategy

To define and explore potentially preventable admissions, we chose specific clinical cases in which the physicians had a difference of opinion on whether the patient’s admission was preventable. From that subset, we identified EM and GM physicians who had differing opinions and invited them to participate in a semi-structured individual interview. Thus we had two embedded units: EM physicians’ and GM physicians’ views on preventable admissions.

Interviews

The interview guide was developed in an iterative process, through literature review, discussion with the research team (consisting of EM and GM physicians), review with a qualitative methods expert, and identification of specific cases. We asked general questions about physician decision-making around the need for admission and then presented the case that the participant was involved in to generate specific discussion about admission decision rationales. The interviews lasted about 1 h and were conducted by research team members.

Data Processing and Analysis

Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. To gain a balance of perspectives, our research team included both EM and GM physicians. We used an exploratory, applied thematic analysis approach to data analysis.34 To fit with this exploratory approach, three team members (AS, MO, APS) independently reviewed a subset of the interviews (n = 5). These team members developed a code book through a process of open coding, revising the codebook through team discussion and refining the codebook through application to subsequent interviews. Once all three team members agreed on the codebook, it was applied to all interview transcripts independently and in duplicate, reconciling disagreement through group consensus. The codes and associated quotations were then analyzed by three team members (LMD, AS, MO), and initial themes were identified. These themes were discussed with a qualitative expert (APS) and content expert (DTK), and major themes were agreed upon by consensus. The team discussed comparisons between EM and GM physicians regarding the phenomenon of potentially preventable admissions. Through group review and consensus, themes were organized into larger domains that encompassed all of the major themes. Data analysis was performed simultaneously with data collection, and interviews were conducted until no new themes were identified by the research team.

RESULTS

Quantitative Results

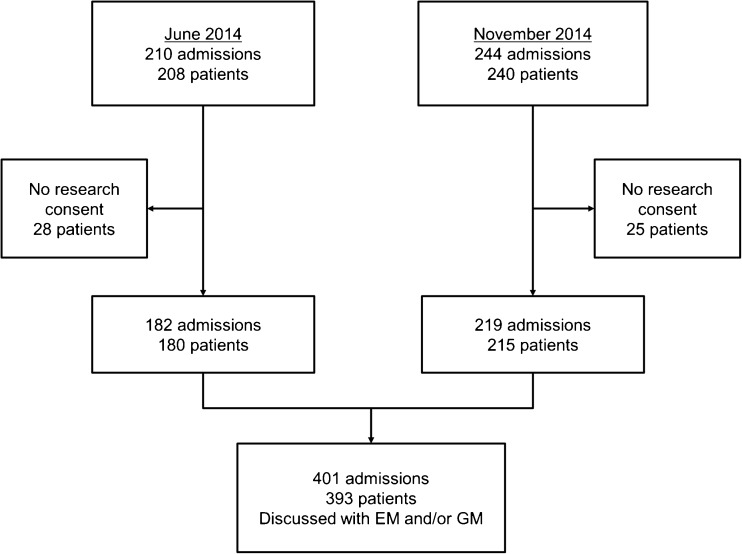

For this study, we included 396 patients, accounting for 401 admissions (Fig. 1). Responses were included for 44 EM physicians and 38 GM physicians. The overall rate of potentially preventable admissions at our institution over this period was 90/401 (22.2%) admissions. EM physicians identified 22/401 (5.5%) admissions and GM physicians identified 76/401 (19%) admissions as potentially preventable, with slight agreement (Cohen’s κ = 0.10). There was no difference in agreement on primary admission diagnosis between potentially preventable and control admissions (78.8% vs. 79.1%, p = 0.82).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included patient admissions. During the study period, there were a total of 448 patients with 454 admissions. Fifty-three patients did not consent to research and were excluded, resulting in a total of 393 patients with 401 admissions.

Comparing potentially preventable admissions to control admissions, there was no significant difference in patient age, sex, race, insurance, location of residence, admission level of care, primary care provider location, CCI, ECOG performance status, ED arrival time, ED arrival day, hospital admission time, or hospital admission day (Table 1). Potentially preventable admissions had shorter length of stay than control admissions (2.1 vs. 3.6 days, p < 0.001). There were no differences between potentially preventable and control admissions for other patient outcomes, including ED length of stay, discharge level of care, 30-day revisit to the ED, 30-day readmission to the hospital, or in-hospital mortality (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient and Admission Characteristics Associated with Potentially Preventable Admissions

| Potentially Preventable (N = 90) |

Control (N = 311) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 60.7 (20.9) | 64.9 (19.1) | 0.074 |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| Female | 52 (58%) | 144 (46%) | 0.072 |

| Race, no. (%) | 0.111 | ||

| White | 76 (84%) | 283 (91%) | |

| Non-white | 14 (16%) | 28 (9%) | |

| Insurance, no. (%) | 0.790 | ||

| Government | 62 (69%) | 223 (72%) | |

| Non-government | 27 (30%) | 83 (27%) | |

| Uninsured | 1 (1%) | 5 (2%) | |

| Location of residence, no. (%) | 0.374 | ||

| Local (surrounding counties) | 73 (81%) | 238 (77%) | |

| Regional (<120 miles) | 6 (7%) | 36 (12%) | |

| National | 11 (12%) | 33 (11%) | |

| International | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Admission level of care, no. (%) | 0.332 | ||

| Assisted living | 1 (1%) | 18 (6%) | |

| Home with assistance | 10 (11%) | 34 (11%) | |

| Home without assistance | 70 (78%) | 231 (74%) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 9 (10%) | 28 (9%) | |

| Primary care provider (PCP) location, no. (%) | 0.178 | ||

| External | 23 (26%) | 104 (33%) | |

| Internal | 63 (70%) | 201 (65%) | |

| No PCP or unknown | 4 (4%) | 6 (2%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 1.84 (2.27) | 1.9 (2.12) | 0.831 |

| ECOG score on admission, no. (%) | 0.773 | ||

| 0 | 3 (3%) | 10 (3%) | |

| 1 | 31 (34%) | 103 (33%) | |

| 2 | 35 (39%) | 118 (38%) | |

| 3 | 21 (23%) | 74 (24%) | |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 6 (2%) | |

| ED arrival time, no. (%) | 0.499 | ||

| Day | 42 (47%) | 167 (54%) | |

| Evening | 32 (36%) | 97 (31%) | |

| Night | 16 (18%) | 47 (15%) | |

| ED arrival day, no. (%) | 0.789 | ||

| Weekday | 67 (74%) | 238 (77%) | |

| Weekend | 23 (26%) | 73 (24%) | |

| Hospital admission time, no. (%) | 0.840 | ||

| Day | 30 (33%) | 106 (34%) | |

| Evening | 35 (39%) | 111 (36%) | |

| Night | 25 (28%) | 94 (30%) | |

| Hospital admission day, (no. %) | 0.963 | ||

| Weekday | 68 (76%) | 232 (75%) | |

| Weekend | 22 (24%) | 79 (25%) |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Table 2.

Patient Outcomes and Associations with Potentially Preventable Admissions

| Potentially Preventable (N = 90) | Control (N = 311) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED length of stay (h), mean (SD) | 4.4 (1.6) | 4.6 (2.2) | 0.386 |

| Hospital length of stay (days), mean (SD) | 2.1 (2.1) | 4.0 (4.6) | <0.001 |

| Discharge level of care, no. (%) | 0.609 | ||

| Home | 70 (78%) | 226 (73%) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 15 (17%) | 62 (20%) | |

| Other facility | 5 (6%) | 19 (6%) | |

| Died | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | |

| 30-Day revisit to ED, no. (%) | 17 (19%) | 54 (17%) | 0.826 |

| 30-Day readmission, no. (%) | 19 (21%) | 55 (18%) | 0.624 |

| In-hospital mortality, no. (%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 0.849 |

Qualitative Case Study

Nineteen attending physicians were interviewed—ten EM physicians ranging from 1 to 32 years (median 11 years) in practice, and nine GM physicians ranging from 1 to 30 years (median 5 years) in practice. EM and GM providers highlighted multiple themes within the domains of provider, patient, and system factors.

Provider Factors

Admission decisions were affected by provider factors, including differences in provider roles, risk–benefit assessment, and outpatient access.

Provider Roles

Participants identified a difference in provider roles leading to different perspectives on preventable admissions, wherein the EM physician triages and the GM physician manages patients. A case that highlighted this difference in provider roles was an 84-year-old woman who presented with acute left facial droop and was brought by ambulance to the ED, where the stroke team was contacted. A CT of her head was normal and her symptoms resolved in the ED. She was admitted for further work-up for poor oral intake and failure to thrive. The EM physician completed the stroke evaluation and admitted the patient to a GM hospital service for work-up and management of her failure to thrive.

An EM physician explained, “[EM physicians] are trained to look at the most severe things first. [GM physicians] are trained to address the most common things first.” Another EM physician said, “We do not make a differential diagnosis in EM; we do risk stratification,” and “Our training is different. We think in terms of worst-case scenarios.” Another EM physician agreed: “We view our role to rule out life-threatening etiologies. Inpatient medicine service is looking at a more holistic approach to managing things over a long term.” Another EM physician similarly stated, “I think of the worst things first and like to rule them out. If I couldn’t, that would stress me out. I think that’s why they [EM and GM] are different specialties.”

A GM physician noted the difference in provider roles: “Their job is not to be a diagnostician, but to evaluate, stabilize, and triage.” Another stated, “The main role of the emergency room is to triage. The main role of the internist is to diagnose and treat.” This was summarized by a GM physician: “I have not really done their job and they have not really done my job. The perception of risk and what needs to be done to manage, may be different.” Therefore, provider factors, including provider roles in triage and management, impact the clinical decision-making for hospital admission.

Risk–Benefit Assessment

Another provider factor that affects clinical decision-making for hospital admission is the difference in assessment of risk and benefit. This difference was most apparent in cases where an admission decision was not clear-cut, what both groups of providers called the “gray zone.” Gray zone decisions revealed that EM physicians place greater risk on sending patients home, whereas GM physicians place higher risk on admitting patients to the hospital. A case in point involved a young woman with chronic dyspnea and with a previous extensive work-up at an outside hospital, who presented to the ED upon arriving in town for a prearranged outpatient evaluation scheduled for the following day. She was admitted and discharged the next day, but she missed her first outpatient appointment and was upset about the hospital bill.

EM physicians are more likely to accept the risk of hospital admission over the risk of clinical decline at home. An EM physician reflected on a case: “In hindsight, it’s always very easy to say that it was a total waste of resources, but you don’t know, because the same patient can go in both directions. If you have 100 patients, and 99 you admit and nothing happens, and one has something happen, should you trade the 99 for the one?” Another agreed: “You might need to keep [the patient] in the hospital overnight to ensure they have a positive, as opposed to a negative, trajectory.” This was also evident when an EM physician was asked why GM might view an admission decision differently, and commented: “[The patient] did not have a life-threatening diagnosis and did not deteriorate. The patient ended up with complete benign presentation, basically lack of bad outcome.”

GM physicians are more likely to view hospital admission as high risk when the patient requires no further intervention while in the hospital, in view of the risk of infection and delirium and the cost of hospitalization. One GM physician explained patient cost: “[Patients] do not understand the difference between observation admission and hospital admission…When they find out they were charged $77/h and for every pill administered, this sometimes alters their expectations.” This was summarized by a GM physician: “I think if you are an admitting physician, your default is going to be to try to do less. However, if you are an ER doctor and you have a patient that is on the border line, it is on you. [A GM physician’s] default is they don’t need to be admitted, whereas the ER is going to admit them. I think that is a huge part of the discrepancy.”

Outpatient Access

A final difference in provider factors affecting clinical decision-making around potentially preventable admissions was access to outpatient resources. This was illustrated in the case of a previously healthy 68-year-old man who presented to the ED with new dyspnea on exertion. A chest x-ray demonstrated a large right-sided pleural effusion. There was concern for malignancy, and he was admitted for evaluation. The EM physician noted that “If you find cancer on an x-ray, and a patient does not have an oncologist, there is no way to resolve that in the emergency department without appropriate referral mechanisms.” The GM physician similarly remarked that “the [EM] physician did not have ready access to have [the patient] plugged in. I had the resources to be able to get the patient’s follow-up, and [the EM physician] did not.”

An EM physician explained, “[GM physicians] know resources better than we know resources.” An EM physician noted that they would prefer having GM physicians provide their expertise in real time so that admissions could be avoided. Another provided an example of a patient with a rheumatologic disease: “[The GM physician] might say, if they were to see the patient, that they would start steroids and see them again in a week. Then it makes sense for us to do the same thing. Having access to some of that expertise would be helpful.”

GM physicians agreed that EM physicians should not be expected to know how to arrange for subspecialty care in the outpatient setting. Another GM physician agreed, reflecting on a time when an EM physician called for advice, asking, “What do you think we can do for this patient? Is there some way to keep this patient out of the hospital?” This physician noted that this communication helped “facilitate the process of getting some of those gray area patients expedited outpatient follow-up and avoiding admission.” This was summarized by a GM physician: “There will always be some sort of conflict or area where we disagree in the gray zone. I think that is the most challenging part, and I think that our communication helps best with that.”

Patient Factors

Patient factors affecting differences in clinical decision-making between EM and GM included patient acuity and diversity. A case highlighting this difference involved an 80-year-old man with benign prostate hypertrophy who presented to the ED with fever of 39.2 C and dysuria, and was found to have a urinary tract infection. He was hemodynamically stable. He was treated with 2 L of intravenous fluid and antibiotics and was admitted to the hospital. He remained stable overnight and was discharged the next day.

As an EM physician observed, “We operate on different populations.” The patients in the ED have higher acuity and are more diverse than those in the hospital; ED patients will need intensive care and emergency surgery more often than patients on the GM service. Another EM physician went on to explain, “What [GM physicians] don't understand is that our patient population is different. The fact that [the patient] got to the emergency department, they are a high-risk pool. We’re not talking about the same patient population anymore.”

Patients seen by GM physicians are often less acutely ill. One GM physician described an interaction with an EM physician regarding the case of an 80-year-old woman with abdominal pain: “If I were to see this patient, there is no way I would send to her to the CT scan. The [EM physician] explained that the group of patients self-selected to present to the emergency room is inherently different than the group of patients that present to clinic. This is a very valid point. [EM physicians] are seeing a sicker group, a different population. They are seeing the bad stuff or the rare stuff.” Again, a GM physician pointed out the difference in patient acuity: “The ED tends to be busy with very acute patients who have rapid needs, versus in the hospital, where they are somewhat stabilized”. Another GM physician explained the difference in patient type; “The breadth of patients we see on the hospital ward are different than the breadth of patients seen in the ED. [EM physicians] also admit patients to the ICU (intensive care unit).” Both specialties noted that the difference in patient acuity and type affects clinical decision-making.

System Factors

System factors affecting clinical decision-making include time pressures and competing demands. This was highlighted in the case of a 44-year-old man with heart failure who presented with shortness of breath. Both the EM and GM physician noted the difference in the amount of time available to assess the patient, resulting in different clinical decisions. The EM physician had planned for admission and started diuretic therapy. By the time the GM physician received the patient for admission, the patient had improved.

An EM physician explained the difference in time pressure: “The inpatient team has had more data, most importantly being time.” Another EM physician highlighted that “chest pain in the emergency department is difficult to risk-stratify, but after 6 h of observation, risk stratification becomes significantly easier. When the patient has had time for three negative troponins and normal electrolytes, it is significantly easier.” When discussing the reason for a discrepancy in the decision for admission, a GM provider noted, “I had the beauty of hindsight, and [EM physicians] don’t.” Another GM physician agreed: “It becomes a little retrospective.” As one GM physician summarized, “As a hospitalist, I don’t think we give the ED enough credit. It’s really easy to be a Monday morning quarterback.”

An EM physician went on to explain competing demands in the ED: “If the patient is bordering for going home or coming in, those are the patients that I want to spend the least time on, because that is at the expense of patients who are really sick.” A GM physician agreed: “The ED tends to be busy, tends to be with very acute patients who have rapid needs, versus in the hospital, for these patients, not always but at least partially worked up, and hopefully somewhat stabilized, and so it isn’t as much urgency or time pressure to complete everything.” Another GM physician concurred: “It’s easier for [GM physicians] to think about patients in the long term. Emergency medicine has to make decisions quickly compared to us. We have sometimes days to make a decision whether the patient can go home; they need to make the decision more quickly. Our timelines are different.” The difference in perspectives on admission decisions is influenced by the system factors of time pressures and competing demands.

DISCUSSION

Potentially preventable admissions are a source of increased cost to the health system, and have been identified as a marker of healthcare quality.15 In this study, physicians identified one in five hospital admissions as potentially preventable. We found no significant associations between potentially preventable admissions and patient or admission characteristics. Potentially preventable admissions had shorter length of hospital stay than control admissions. EM and GM physicians identified several patient, system, and provider factors that affected decisions regarding hospital admission, most notably the difference in provider roles, risk–benefit assessment, and knowledge of outpatient access. These differences highlight possible opportunities for future exploration of physician decision-making with regard to identifying potentially preventable admissions.

The results of this study are consistent with those of previous studies that were unable to identify objective markers to aid in identification of potentially preventable admissions.7–9 No association was found for patient age, consistent with a study by Chan et al., who posited that previous associations with age may have suffered from confounding.7, 8, 10, 13, 14 Other patient-related factors, including access to primary care, functional status, and comorbidities, also showed no association with potentially preventable admissions.14, 17, 21, 31 Similarly, no association was identified for system-related factors, such as time or day of presentation to the ED or length of stay in the ED.8, 10 Outcomes such as readmission rate and mortality also were not affected.8 This study thus reinforces the results of previous studies demonstrating that physicians are best able to identify potentially preventable hospitalizations without negatively impacting patient outcomes.9, 15–19

While we were unable to identify associations with objective markers, we characterized a difference in clinical decision-making between EM and GM physicians regarding the need for hospital admission.8, 20, 24–26, 28, 35–37 Factors that affected decisions on potentially preventable admissions fit into the three major domains of patient, provider, and system factors, aligning with a similar study exploring factors influencing the quality of healthcare.38 Commonly used quality improvement methods begin with root cause analysis, and the domains and themes identified in this study can drive quality improvement efforts aimed at addressing potentially preventable admissions.39 When exploring reasons for differences in decisions, we found the difference to be most notable in cases where patients were considered to be in the “gray zone”, when there was no clear decision for hospital admission.28, 40 Patients were often in this gray zone when risk and benefit appeared to be equal, or outpatient evaluation was unclear. In these cases, EM physicians best estimated the risk–benefit between risk of potential clinical decline at home and potential outpatient evaluation in order to determine the need for hospital admission.22, 41, 42 After the decision for hospital admission had already been made by the EM physician, the GM physicians would then assess the risk–benefit of hospitalization and potential for outpatient evaluation from the GM perspective.22, 41, 42 At this point, where patient care transitions from EM to GM, EM physicians can best attest to risk of clinical decline at home, whereas GM physicians can best attest to optimal inpatient or outpatient management.22, 27, 28, 35, 42

Previous studies have shown that this point of transition from EM to GM physicians provides an opportunity for improvement in patient care.23, 27 When GM physicians participate in the care of patients in the ED, patients benefit by having adjustments to management plans and lower rates of hospitalization.23, 27 However, previous studies involved the transitioning of care from EM to GM while patients remained in the ED.23, 27 Instead of transitioning care, collaboration of care may offer more information and therefore the ability to better assess the need for hospitalization for patients in the gray zone.23, 27, 43 For example, EM physicians are able to offer expertise in stabilization and risk of decompensation at home, while GM physicians are able to offer expertise in optimal inpatient versus outpatient management. This collaboration benefits the patient by providing an individualized and comprehensive management strategy that incorporates both providers’ perspectives. This will enable a greater number of potential hospitalizations to be identified as preventable before the admission occurs, thus providing the opportunity to avoid unnecessary hospitalization.23, 27

There were limitations to this study. Only those patients who were admitted to the hospital were evaluated, and patients discharged from the ED were not included. Further research should compare outcomes between potentially preventable admissions and patients discharged from the ED. We also did not include patients admitted from clinic, which could be another source of potentially preventable admissions.

CONCLUSIONS

Physicians determined that one in five hospital admissions were potentially preventable, representing a possible source of unnecessary healthcare cost. Collaboration between EM and GM physicians around patients in the “gray zone,” focusing on the risk of deterioration at home, the risk of hospitalization, the cost to the patient, and the presence of outpatient resources, may provide an avenue for reducing potentially preventable admissions and lowering healthcare expenditures.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors each declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD. 2016. [PubMed]

- 2.Weiss AJ, Wier LM, Stocks C, Blanchard J. Overview of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2011: Statistical Brief #174. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006-. 2014. [PubMed]

- 3.Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, et al. The Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States. Rand Health Q. 2013;3(2):3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fingar KR, Barrett ML, Elixhauser A, Stocks C, Steiner CA. Trends in Potentially Preventable Inpatient Hospital Admissions and Emergency Department Visits: Statistical Brief #195. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006-. 2015. [PubMed]

- 5.Moy E, Chang E, Barrett M. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Potentially preventable hospitalizations - United States, 2001-2009. MMWR Suppl. 2013;62(3):139–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995;274(4):305–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530040033037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peck JS, Benneyan JC, Nightingale DJ, Gaehde SA. Predicting emergency department inpatient admissions to improve same-day patient flow. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(9):E1045–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean NC, Jones JP, Aronsky D, et al. Hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: variability among physicians in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;59(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graff L, Mucci D, Radford MJ. Decision to hospitalize: objective diagnosis-related group criteria versus clinical judgment. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(9):943–52. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(88)80677-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leegon J, Jones I, Lanaghan K, Aronsky D. Predicting hospital admission for Emergency Department patients using a Bayesian network. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2005:1022. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sun Y, Heng BH, Tay SY, Seow E. Predicting hospital admissions at emergency department triage using routine administrative data. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(8):844–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruger JP, Lewis LM, Richter CJ. Identifying high-risk patients for triage and resource allocation in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25(7):794–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts MV, Baird W, Kerr P, O'Reilly S. Can an emergency department-based Clinical Decision Unit successfully utilize alternatives to emergency hospitalization? Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):89–96. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32832f05bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan T, Arendts G, Stevens M. Variables that predict admission to hospital from an emergency department observation unit. Emerg Med Australas. 2008;20(3):216–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable Admissions on a General Medicine Service: Prevalence, Causes and Comparison with AHRQ Prevention Quality Indicators-A Cross-Sectional Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597–601. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3615-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaghasiya MR, Murphy M, O'Flynn D, Shetty A. The emergency department prediction of disposition (EPOD) study. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2014;17(4):161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aenj.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors Influencing Hospital Admission of Non-critically Ill Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department: a Cross-sectional Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):37–44. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3438-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh P, Doyle D, McQuillen KK, et al. Comparison of the evaluations of a case-based reasoning decision support tool by specialist expert reviewers with those of end users. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9(2):74–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marriott D, Turner Z, Robin N, Singh S. To admit or not to admit? The suitability of critical care admission criteria. Crit Care. 2011;16(Supp1 1):511. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnato AE, Hsu HE, Bryce CL, et al. Using simulation to isolate physician variation in intensive care unit admission decision making for critically ill elders with end-stage cancer: a pilot feasibility study. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(12):3156–63. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f40d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNulty JE, Hampers LC, Krug SE. Primary care and emergency department decision making. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(11):1266–70. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.11.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmonds RL, Shaw A, Purdy S. Factors influencing professional decision making on unplanned hospital admission: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(604):e750–6. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X658278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chadaga SR, Shockley L, Keniston A. Hospitalist-led medicine emergency department team: associations with throughput, timeliness of patient care, and satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):562–6. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coates D, Rawstorne S, Benger J. Can emergency care practitioners differentiate between an avoided emergency department attendance and an avoided admission? Emerg Med J. 2012;29(10):838–41. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2011-200484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calder LA, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, et al. Mapping out the emergency department disposition decision for high-acuity patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):567–576.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu KH, Chen IC, Li CJ, Li WC, Lee WH. The influence of physician seniority on disparities of admit/discharge decision making for ED patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(8):1555–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briones A, Markoff B, Kathuria N, et al. A model of a hospitalist role in the care of admitted patients in the emergency department. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):360–4. doi: 10.1002/jhm.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence S, Sullivan C, Patel N, Spencer L, Sinnott M, Eley R. Admission of medical patients from the emergency department: An assessment of the attitudes, perspectives and practices of internal medicine and emergency medicine trainees. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(4):391–8. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hollander JE, Sease KL, Sparano DM, Sites FD, Shofer FS, Baxt WG. Effects of neural network feedback to physicians on admit/discharge decision for emergency department patients with chest pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zohar M, Hadas Z, Modan B. Factors affecting the decision to admit mental patients in a community hospital. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175(5):301–5. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilber ST, Blanda M, Gerson LW. Does functional decline prompt emergency department visits and admission in older patients? Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(6):680–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2014.

- 33.Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers. Qual Rep. 2008;13(4):544–59. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guest G, MacQueesn KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovacs G, Croskerry P. Clinical decision making: an emergency medicine perspective. Academic Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(9):947–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krol D. An Internist’s Experience As The Emergency Room Doctor. Available at: https://www.dailydosemd.com/internists-experience-emergency-room-doctor/. Accessed December 4, 2017.

- 37.Calder LA, Arnason T, Vaillancourt C, Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Forster AJ. How do emergency physicians make discharge decisions? Emerg Med J. 2015;32(1):9–14. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosadeghrad AM. Factors influencing healthcare service quality. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(2):77–89. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kautz JM, Armistead NS, Starr SR. Quality Improvement. In: Skochelak SE, Hawkins RE, Lawson LE, Starr SR, Borkan JM, Gonzalo JD, editors. Health Systems Science. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 68–80. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorrindo T, Goldfarb E, Chevalier L, et al. Interprofessional differences in disposition decisions: results from a standardized web-based patient assessment. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(8):808–11. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emerman CL. National reporting of emergency department length of stay: challenges, opportunities, and risks. JAMA. 2012;307(5):511–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Connor E, Gatien M, Weir C, Calder L. Evaluating the effect of emergency department crowding on triage destination. Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1865-1380-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pollack CV, Jr, Amin A, Talan DA. Emergency medicine and hospital medicine: a call for collaboration. Am J Med. 2012;125(8):826.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]