Abstract

Background

Hospitals are standard of care for acute illness, but hospitals can be unsafe, uncomfortable, and expensive. Providing substitutive hospital-level care in a patient’s home potentially reduces cost while maintaining or improving quality, safety, and patient experience, although evidence from randomized controlled trials in the US is lacking.

Objective

Determine if home hospital care reduces cost while maintaining quality, safety, and patient experience.

Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Participants

Adults admitted via the emergency department with any infection or exacerbation of heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or asthma.

Intervention

Home hospital care, including nurse and physician home visits, intravenous medications, continuous monitoring, video communication, and point-of-care testing.

Main Measures

Primary outcome was direct cost of the acute care episode. Secondary outcomes included utilization, 30-day cost, physical activity, and patient experience.

Key Results

Nine patients were randomized to home, 11 to usual care. Median direct cost of the acute care episode for home patients was 52% (IQR, 28%; p = 0.05) lower than for control patients. During the care episode, home patients had fewer laboratory orders (median per admission: 6 vs. 19; p < 0.01) and less often received consultations (0% vs. 27%; p = 0.04). Home patients were more physically active (median minutes, 209 vs. 78; p < 0.01), with a trend toward more sleep. No adverse events occurred in home patients, one occurred in control patients. Median direct cost for the acute care plus 30-day post-discharge period for home patients was 67% (IQR, 77%; p < 0.01) lower, with trends toward less use of home-care services (22% vs. 55%; p = 0.08) and fewer readmissions (11% vs. 36%; p = 0.32). Patient experience was similar in both groups.

Conclusions

The use of substitutive home-hospitalization compared to in-hospital usual care reduced cost and utilization and improved physical activity. No significant differences in quality, safety, and patient experience were noted, with more definitive results awaiting a larger trial.

Trial Registration NCT02864420.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4307-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: home hospital, hospital at home, hospital alternative, home-based care

INTRODUCTION

Hospitals are the standard of care for acute illness in the US, but hospital care is expensive and often unsafe, particularly for older individuals.1 While admitted, 20% suffer delirium,2 over 5% contract hospital-acquired infections,3 and many lose functional status that is never regained.4 Timely access to inpatient care is often poor: many hospital wards are typically over 100% capacity, and emergency department (ED) waits can be protracted. Moreover, hospital care is increasingly costly, accounting for about one-third of total medical expenditures, and is a leading cause of patient debt.5

A “home hospital” is home-based provision of acute services usually associated with the traditional inpatient hospital setting.6 Prior work suggests home hospital care can reduce cost, maintain quality and safety, and improve patient experience for selected acutely ill adults who require traditional hospital-level care.7–15 While home hospital care is familiar in several developed countries,16 only two non-randomized studies have been conducted in the US.

We sought to demonstrate the cost, safety, quality, and patient experience of substitutive hospital-level care in the home through a pilot randomized controlled trial.

METHODS

Study Design

This investigator-initiated study was approved by the Partners HealthCare Human Research Committee as more than minimal risk human subject research. It was registered at clinicaltrials.gov, record NCT02864420. All participants provided written informed consent. None of the study’s commercial vendors participated in design, analysis, interpretation, preparation, review, or approval.

We performed a randomized controlled trial at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH, an academic medical center) and Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital (a community hospital) between September 12, 2016, and November 13, 2016. Faulkner hospital was added in the last 3 weeks of the study to increase sample size.

Participants

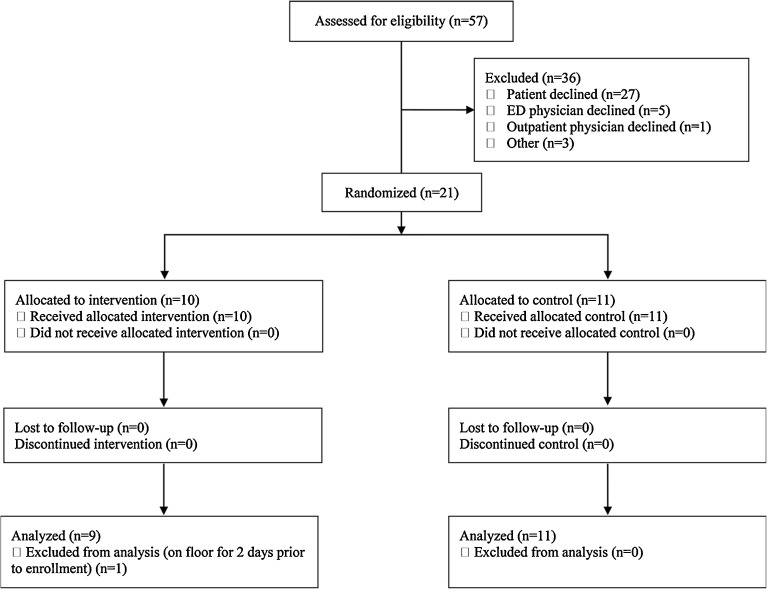

Participants were recruited in the ED. Participants were initially pre-screened by a research assistant to ensure they were adults, were not presenting for trauma or psychiatric evaluation, and lived within our catchment area. After the decision by the ED attending was made to admit a patient, s/he would call the triage attending as per usual protocol to discuss admission. If the patient at hand met inclusion and had no exclusion criteria, and the ED attending was in agreement, then the admission could be held so the home hospital team could assess the patient for eligibility, interest, and consent (Fig. 1). The goal of enrollment was minimal disruption to the ED, for which we tracked various process measures (online eTable 1), demonstrating minimal delays in the ED because of the study protocol.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram. One patient in the home group was excluded from analysis. This patient was a pre-specified “n of one” attempt at a separate model of early transfer to home hospital after stabilization in the traditional hospital

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants were eligible for home hospital if they resided within our catchment area, had capacity to consent, were 18 years old or older, and had a primary diagnosis of any infection, heart failure exacerbation, COPD exacerbation, or asthma exacerbation.

Participants were ineligible to enroll if they were undomiciled, lacked utilities, were in police custody, screened positive for domestic violence,17 or resided in a facility that provided on-site medical care. Participants were also ineligible if peripheral intravenous access could not be obtained in the ED, they required routine administration of intravenous narcotics, they had an acute concomitant condition (e.g., hemorrhage), they could not independently ambulate to a bedside commode, or, as deemed by the home hospital attending, they were likely to require a procedure not available in the home hospital program (e.g., computed tomography, endoscopy, surgery). Patients were also excluded if they were considered at high risk for clinical deterioration based on already validated general and disease-specific risk algorithms (online eAppendix 1). No exclusion was made based on insurance status.

Randomization

After meeting criteria and providing written informed consent, participants were randomized to usual care admission or home hospital admission by research study staff. Randomization was stratified by condition with randomly selected block sizes between 4 and 6 with allocation concealment via sealed envelopes. Given the nature of the study, blinding of patients, study staff, and physicians was not possible.

Intervention

All patients received at a minimum one daily visit from an attending general internist and two daily visits from a home health registered nurse, with additional visits performed as needed. Also tailored to patient need, participants could receive medical meals and the services of a home health aide, social worker, physical therapist, and/or occupational therapist.

Home hospital could provide oxygen therapy, respiratory therapies (e.g., nebulizer), intravenous medications via infusion pump (Smiths Medical, St. Paul, MN), in-home radiology, and point-of-care blood diagnostics. All patients had continuous monitoring of heart rate, respiratory rate, telemetry, movement, falls, and sleep via a small skin patch (physIQ, Chicago, IL; VitalConnect, San Jose, CA). Monitoring was performed through machine-based algorithms, and clinical staff reviewed any alarms produced by these algorithms as part of their clinical care. Participants communicated with their home hospital team via telephone, encrypted video, and encrypted short message service (Everbridge, Burlington, MA). The physician was available 24 hours a day for urgent issues and visits. Criteria for discharge were by design left to the discretion of the home hospital attending. We mandated no treatment pathways or algorithms. Follow-up after discharge was by design no different than usual care.

Participants randomized to the control group received usual care in the hospital, also from an attending general internist, with the addition of the aforementioned skin patch (placed while in the ED). Hospital staff was unaware of the patch’s purpose.

Data Sources and Outcomes

For both groups, we interviewed patients on admission, at discharge, and at 30-days post-discharge. On admission, patients reported their sociodemographics (Table 1) and completed assessments of frailty (PRISMA-7; > 2 indicates frailty),18 cognitive impairment (Ascertain Dementia-8; > 1 indicates cognitive impairment),19 depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2; > 2 indicates depression),20 emotional support (PROMIS Emotional Support 4a; > 17 indicates better than average support),21 health literacy (BRIEF health literacy screening tool; > 17 indicates adequate literacy),22 quality of life (EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale),23 and functional status scores [activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)]. We supplemented sociodemographic data with the hospitals’ electronic health record (EHR) for items such as insurance status.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Home (n = 9) | Control (n = 11) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 65 (28) | 60 (29) | 0.49 |

| Female, n (%) | 2 (22) | 8 (73) | 0.07 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.84 | ||

| White | 4 (44) | 5 (45) | |

| Latino | 4 (44) | 3 (27) | |

| Black | 1 (11) | 3 (27) | |

| Partner status, n (%) | 0.41 | ||

| Partnered | 5 (56) | 6 (55) | |

| Divorced/widowed | 3 (33) | 3 (27) | |

| Single | 1 (11) | 2 (18) | |

| Primary language, n (%) | 0.62 | ||

| English | 6 (67) | 9 (82) | |

| Spanish | 3 (33) | 2 (18) | |

| Insurance, n (%) | 0.17 | ||

| Private | 6 (67) | 3 (27) | |

| Medicare | 3 (33) | 5 (45) | |

| Medicaid | 0 | 3 (27) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.06 | ||

| > 4-year college | 3 (33) | 1 (9) | |

| 4-year college | 1 (11) | 6 (55) | |

| < 4-year college | 1 (11) | 3 (27) | |

| High school | 1 (11) | 1 (9) | |

| < High school | 3 (33) | 0 | |

| Employment, n (%) | 0.33 | ||

| Employed | 5 (56) | 4 (36) | |

| Unemployed | 0 | 3 (27) | |

| Retired | 4 (44) | 4 (36) | |

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | 0.55 | ||

| Never | 4 (44) | 3 (27) | |

| Current | 0 | 2 (18) | |

| Prior | 5 (56) | 6 (55) | |

| PRISMA (0–7), median (IQR) | 2 (1) | 3 (3) | 0.86 |

| Ascertain dementia-8 (0–8), median (IQR) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0.08 |

| Health literacy (4–20), median (IQR)† | 20 (7) | 18 (10) | 0.57 |

| Medication count, median (IQR) | 8 (13) | 10 (14) | 0.93 |

| Comorbidity count, median (IQR)‡ | 7 (7) | 6 (7) | 0.14 |

| Code status: Full code, n (%) | 6 (67) | 10 (91) | 0.28 |

| Yes, surprised if died in 1 year, n (%) | 5 (56) | 8 (73) | 0.64 |

| EuroQol VAS (0–100), median (IQR) | 75 (10) | 65 (25) | 0.05 |

| ADLs (0–6), median (IQR) | 6 (0) | 5 (2) | 0.07 |

| IADLs (0–8), median (IQR) | 8 (2) | 5 (5) | 0.34 |

| PHQ-2 (0–6), median (IQR) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0.04 |

| PROMIS emotional support (4–20), median (IQR) | 20 (2) | 20 (1) | 0.93 |

| Hospital admission in last 6 months, n (%) | 4 (44) | 4 (36) | 1 |

| Emergency department visit in last 6 months, n (%) | 5 (56) | 3 (27) | 0.36 |

Abbreviations: ADLs, activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; IQR, interquartile range; PHQ-2, Patient Health Quesitonnaire-2 (measure of depression); PRISMA, Program of Research to Integrate Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy (measure of frailty); PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; VAS, visual analog scale

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables

†Brief health literacy screener, 4–12: limited; 13–16: marginal; 17–20: adequate

‡Count of patient’s chronic comorbidities

Our primary outcome was direct cost of the acute care episode, calculated as the sum of non-physician labor, supplies, monitoring equipment, medications, labs, radiology, and transport directly attributed to the patient’s care (online eAppendix 2). Both groups used an identical cost calculation, except for transport (not applicable to the hospital group) and non-physician labor. In the home group, we multiplied non-physician labor hours by the hourly direct rate to obtain cost; in the control group, we multiplied non-physician labor hours by the hourly unit-based direct rate (this is our institution’s best-practice in estimating labor and derived directly from their internal accounting system). Administrative costs are considered indirect costs and were not included.

We did not include physician labor because this is customarily separate from traditional hospital costs, and BWH does not utilize a direct care model such as home hospital (e.g., physicians at BWH always work with residents or physician assistants). The attending physician-to-patient ratios for home hospital and BWH are capped at 1:4 and 1:16, respectively. However, the BWH attending physician is assisted by 3 day-time and 2 night-time residents, in effect requiring more physicians per patient than in home hospital. In addition, at nearby academic medical centers that do have direct care models (i.e., no resident or mid-level provider assistance), attendings typically see eight patients and still require overnight attending coverage.

We secondarily studied utilization, safety, quality, and patient experience during the acute care episode. Utilization measures included laboratory orders, radiology studies, consultations, and length of stay, all derived from the EHR (Table 2). Safety measures included adverse events (e.g., falls and standard hospital-acquired conditions), delirium (captured by the Confusion Assessment Method,2 already documented every 8 h at BWH as part of usual care), and the unexpected return to hospital rate (intervention arm only; Table 3). Quality measures included pertinent Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) inpatient quality measures (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in a patient with heart failure of reduced ejection fraction), pain scores, physical activity [exertion (any movement at least as vigorous as slow walking, 0.02 g’s), steps, and upright posture], and sleep. All measures were derived from the EHR, except falls, physical activity, and sleep, which were observed via the skin patch. We considered hospital-acquired disability to be any reduction in a patient’s ADLs or IADLs between admission and discharge.24 Patient experience measures included the Care Transitions Measure (CTM) 3, Picker patient experience questionnaire,25 recommending the hospital experience, and global experience (Table 4). Experience measures were recorded during the 30-day interview.

Table 2.

Patient Utilization

| Measure | Home (n = 9) | Control (n = 11) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay, median days (IQR) | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 0.79 |

| IV medication during admission, n (%) | 6 (67) | 9 (82) | 0.62 |

| Imaging during admission, n (%) | 1 (11) | 5 (45) | 0.16 |

| Consultant session during admission, n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (45) | 0.04 |

| Lab orders per admission, median (IQR) | 6 (6) | 19 (22) | < 0.01 |

| PT/OT session during admission, n (%) | 1 (11) | 3 (27) | 0.59 |

| Disposition, n (%) | 0.08 | ||

| Routine | 7 (78) | 5 (45) | |

| Home Health | 2 (22) | 6 (55) | |

| Primary care visit by 14 days post-discharge, n (%) | 7 (78) | 4 (36) | 0.09 |

| 30-day readmission, n (%) | 1 (11) | 4 (36) | 0.32 |

| 30-day ED presentation, n (%) | 1 (11) | 2 (18) | 1 |

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; IV, intravenous; OT, occupational therapy; PT, physical therapy

Table 3.

Patient Safety

| Measure, n (%) | Home (n = 9) | Control (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Fall | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Delirium | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| DVT/PE | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| New pressure ulcer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Thrombophlebitis at peripheral IV site | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| CAUTI | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Clostridium difficile | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| New MRSA | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| New arrhythmia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Hypokalemia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Acute kidney injury | 0 (0) | 1 (9) |

| Transfer back to hospital | 0 (0) | n/a |

| Mortality during admission | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| > 3 medications added to medication list | 0 (0) | 1 (9) |

| 30-day mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; DVT/PE, deep venous thromboembolism/pulmonary embolism; IV, intravenous; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; n/a, not applicable

Table 4.

Quality, Physical Activity, and Experience

| Measure | Home (n = 9) | Control (n = 11) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of care† | |||

| Pain score (0–10), median (IQR) | 1.5 (4) | 1.4 (4.9) | 1 |

| Inappropriate medication use, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (9) | 1 |

| Foley use, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Restraint use, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Activity each day | |||

| Physical activity, minutes, median (IQR) | 209 (90) | 78 (44) | < 0.01 |

| Sleep, hours, median (IQR) | 5.4 (1.9) | 4.1 (3.0) | 0.33 |

| Steps, median (IQR)‡ | 1820 (3300) | 159 (508) | 0.06 |

| Upright posture, hours, median (IQR) | 4.8 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.8) | < 0.01 |

| Patient experience | |||

| Care transitions measure-3 (3–12), median (IQR) | 12 (0) | 12 (3) | 0.21 |

| Picker questionnaire (0–15), median (IQR) | 15 (4) | 13 (4) | 0.18 |

| Global satisfaction (0–10), median (IQR)§ | 10 (1) | 10 (2) | 0.67 |

| Recommend hospital (0–4), median (IQR)‖ | 4 (0) | 4 (0) | 1 |

Abbreviations: ADLs, activities of daily living; ED, emergency department; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; IQR, interquartile range; IV, intravenous; OT, occupational therapy; PT, physical therapy

*Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for categorical variables

†Standard inpatient quality measures for pneumonia and heart failure (e.g., beta blocker for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, smoking cessation counseling) were achieved equally in both groups and are omitted because of space constraints

‡Two older patients in the home group shuffled while walking, resulting in a step count of almost zero being registered. These outliers drove the large IQR

§Scale: 0 = the worst possible hospital; 10 = the best possible hospital

‖Scale: 0 = definitely would not recommend; 4 = definitely would recommend

We additionally measured cost and utilization in the 30-day post-discharge period using the same cost-accounting method. We tracked readmissions, ED visits, primary care visits, and specialist visits. As we only had access to records from Partners HealthCare (the health system that includes BWH), we asked participants whether they received any health care outside of our health system and added those to the cost estimates. This occurred in only two patients who received a single primary care visit each outside of Partners.

Sample Size Considerations

From previous quasi-experimental data, home hospital reduced the payer (not provider) cost of admission by 20–30% with baseline payments of $7480 (SD $8112).7, 8 To achieve at least 80% power with a type I error rate of 5%, we required 30 patients per arm to detect a 60% relative reduction in costs. While this was an optimistic effect size based on the literature, we anticipated smaller variance based on our local data and randomized design.

We had limited funding and could only continue our pilot for at most 2.25 months. Thus, irrespective of enrollment, we a priori planned to stop the pilot when funds were depleted.

Statistical Methods

Given our small sample size and, in the case of cost, skewed data, we used non-parametric tests to compare home hospital and usual care, presenting results as median and interquartile range (IQR). We compared characteristics of participants in both groups with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for dichotomous and categorical variables. We present cost data as percent change from control given the sensitive nature of these data.

All tests for significance used a two-sided p value of 0.05. We performed all analyses in SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 57 patients were assessed for entry into the study; 21 were enrolled and randomized (Figure; details of those declined/lost, online eTable 2). Twenty-seven patients declined enrollment; six physicians declined to allow their patients to enroll. All patients enrolled received their allocated treatment and were followed until 30-days post discharge. One patient in the home group was excluded from analysis. This patient was a pre-specified “n of one” attempt at a separate model of early transfer to home hospital after stabilization in the traditional hospital. As a result, this patient had been in the hospital for 2 full days prior to enrollment. While we learned valuable lessons about this model, this patient is not comparable to the other home hospital patients.

The nine patients randomized home had a median age of 65 years (IQR, 28), 22% were female, 44% White, and 56% partnered (Table 1). Most (67%) spoke English as their primary language, 67% had private insurance, 56% were employed, and 33% had less than a high school education. The 11 patients randomized to control were not statistically different, although they trended toward younger (median age 60 years [IQR 29]), more often female (73%), more English-speaking (82%), less privately insured (27%), more educated (55% with college degree), and more unemployed (27%).

Patients’ clinical characteristics were similar between groups (Table 1). In the home group, patients had mild frailty (2/7 [IQR, 2]), unlikely dementia and depression (AD-8 0/8 [IQR, 0], PHQ2 0/6 [IQR, 0]), excellent functional status (ADLs 6/6 [IQR, 0] and IADLs 8/8 [IQR, 2]), high health literacy (19.5 [IQR, 7]), and excellent social support (20/20 [IQR, 2]). Patients reported moderately high quality of life (75/100 [IQR, 10]. Patients in the control group had significantly more depression.

Despite reassuring self-reported characteristics, patients in both groups were chronically ill and frequently used care. In the last 6 months, 44% of home group patients had been admitted; 56% had visited the ED. Home group patients had seven (IQR, 7) chronic comorbidities and took eight (IQR, 13) chronic medications.

Cost and Utilization

Median direct cost of the acute care episode for home patients was 52% (IQR, 28%; p = 0.05) lower than for control patients.

Median length of stay was 3.0 days in both groups (p = 0.8; Table 2). During the care episode, home patients had fewer laboratory orders (6 vs. 19; p < 0.01) and received consultations less often (0% vs. 27%; p = 0.04), with a trend toward less imaging. Each day, home patients received a median of one physician visit (range: 1 to 3) and two nurse visits (range: 2 to 4).

Median direct costs for the acute care plus 30-day post-discharge period for home patients was 67% (IQR, 77%; p < 0.01) lower, with non-significant trends toward less use of home health services, fewer readmissions, and improved follow-up with their primary care clinicians within 14 days of discharge (Table 2).

Safety, Quality, and Activity

No adverse safety events and no transfers back to hospital occurred in home patients (Table 3). One control patient had nosocomial acute kidney injury. Neither group used indwelling urinary catheters or restraints.

Pain scores were similar in both groups (Table 3). Both groups were similarly provided pneumococcal vaccination, influenza vaccination, smoking cessation counseling, and the CMS heart failure measures (e.g., beta blocker for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) when applicable.

Home patients had more minutes of physical activity per day (median minutes, 209 [IQR, 90] vs. 78 [IQR, 44]; p < 0.01), spent more time upright (median hours per day, 4.8 [IQR, 1.4] vs. 2.7 [IQR, 1.8]; p < 0.01), and had a trend toward more sleep (Table 4).

There was a trend toward more hospital acquired disability in the control group: ADLs and IADLs were respectively worse at discharge in 9% and 18% of the control group vs. 0% and 0% of the home group.

Patient Experience

Patients in the home and control group reported high global satisfaction and would always recommend their experience to others (Table 4). Home patients had a trend toward better Picker experience scores.

DISCUSSION

In this small two-site pilot study, providing care to acutely ill adults at home compared to the traditional hospital reduced cost, decreased utilization, and improved physical activity, without appreciably changing quality, safety, or patient experience. We also observed trends toward reduced hospital-acquired disability, readmission, and disposition to home health services among home hospital patients.

The goal of the home hospital model is to get the “right care to the right patient at the right time.” Home hospital reduces cost, for example, because it reduces nursing labor (similar patient:nurse ratio, but 2 visits at home versus 24 h care in the hospital), reduces utilization (fewer laboratory draws and consultations), likely improves follow-up with primary care, and possibly reduces readmission (online eAppendix 2 for cost details). It delivers care in a more patient-centered manner: patients can be surrounded by their family and friends, eat their own food, move around in their own home, and sleep in their own bed, with the supports of the home hospital team. The home is also an ideal place to empower patients and caregivers around self-management during and after the episode. Performing medication reconciliation with the medicine cabinet in sight and dietary education in a patient’s kitchen are powerful touch points. Discharge without home health or in a timely manner was also likely facilitated, as the home hospital team had greater confidence in a patient’s ability to function at home because they were already in the home setting.

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial of home hospital performed in the US. Importantly, what constitutes a “home hospital” is highly variable both nationally and internationally.26, 27 Our model involves a physician in the home, delivers twice-daily nurse visits and 24-h physician coverage, provides acute care similar to that received in a traditional hospital to acutely ill patients who otherwise would have been admitted, and offers cutting edge connectivity (continuous monitoring, video, and texting). This differs from most home-based models in its ability to handle high patient acuity and enmesh physician medical decision-making with a patient-tailored care team. Careful patient selection also minimized risk.

Previous work corroborates our findings. Others providing substitutive care to acutely ill patients have shown reduced cost (20–30%) and decreased utilization, all while maintaining or improving on quality, safety, and patient experience.7, 8 Two randomized controlled trials in Italy for patients presenting with COPD and heart failure exacerbations echo these findings and demonstrated reductions in readmission.9, 28 An older randomized controlled trial in Australia found a 51% reduction in cost.13, 29 Our findings regarding physical activity build on other work.15, 24 Our study included patients of a somewhat younger median age than others.

Our study has limitations. First, our small sample size resulted in unequal groups and insufficient ability to adjust for some clinically important differences between them. In a larger trial, we would expect these differences to be decreased. Second, the small sample size left us underpowered to detect significant differences for many of our secondary outcomes. However, this study was designed as a pilot, and it is notable that even with our small sample size we were able to detect statistically significant differences in our primary outcome and several secondary outcomes because of the large effect sizes. Third, we only recruited from two, albeit distinct sites, limiting generalizability. For example, our cost calculations may be less valid at an institution with different staffing structures and patient to clinician ratios. Fourth, 63% of patients declined to participate, approximately the inverse of prior work (online eTable 2).7 This was likely due to our robust randomization scheme, which only allowed us to approach patients just before “rolling upstairs,” a time when most patients had already mentally prepared for traditional admission. It may also be reflective of a patient culture that is not yet comfortable with home hospitalization. On the other hand, this approach greatly minimized selection bias between the enrolled patients in the two arms of the study.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite important incremental improvements in traditional hospitals, the structure and care delivered are still very reminiscent of hospitals 50 years ago. Some hospital structures have persisted for over 100 years. Reimagining the best place to care for select acutely ill adults holds enormous potential.

This randomized controlled pilot of substitutive home hospital care demonstrates improvements in cost, utilization, and physical activity while likely maintaining quality, safety, and experience, with more definitive results awaiting a larger trial.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 31 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the home hospital clinicians who cared for the home hospital patients.

The authors also graciously acknowledge the various departments at Brigham Health who were instrumental to the success of the home hospital program: Cardiology, Emergency Medicine, General Internal Medicine and Primary Care, Hospital Medicine, Pharmacy, Laboratory, and Population Health.

Financial Support

Partners HealthCare Population Health Management provided funding support for the home hospital clinical program.

Dr. Levine received funding support from an Institutional National Research Service Award from (T32HP10251) and the Ryoichi Sasakawa Fellowship Fund.

The NIH had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Prior Presentations

Society of General Internal Medicine—national conference; Washington, DC, 2017. Awarded Lipkin Award.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the mobile acute care of the elderly (MACE) service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990–996. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210–220. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National and State Healthcare-Associated Infections Progress Report. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/hai/surveillance/progress-report/index.html. Accessed 10 December 2017.

- 4.Counsell SR, Holder CM, Liebenauer LL, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: a randomized controlled trial of acute care for elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1572–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, MD; 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf. Accessed December 10, 2017. [PubMed]

- 6.Leff B. Defining and disseminating the hospital-at-home model. CMAJ. 2009;180(2):156–157. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leff B, Burton L, Mader SL, et al. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(11):798–808. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cryer L, Shannon SB, Van Amsterdam M, Leff B. Costs for “hospital at home” patients were 19 percent lower, with equal or better outcomes compared to similar inpatients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(6):1237–1243. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tibaldi V, Isaia G, Scarafiotti C, et al. Hospital at home for elderly patients with acute decompensation of chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caplan GA, Sulaiman NS, Mangin DA, Aimonino Ricauda N, Wilson AD, Barclay L. A meta-analysis of “hospital in the home”. Med J Aust. 2012;197(9):512–519. doi: 10.5694/mja12.10480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;180(2):175–182. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. In: Shepperd S, et al., editors. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016. p. CD007491. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Board N, Brennan N, Caplan GA. A randomised controlled trial of the costs of hospital as compared with hospital in the home for acute medical patients. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;24(3):305–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2000.tb01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caplan GA, Coconis J, Board N, Sayers A, Woods J. Does home treatment affect delirium? A randomised controlled trial of rehabilitation of elderly and care at home or usual treatment (The REACH-OUT trial) Age Ageing. 2006;35(1):53–60. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caplan GA, Coconis J, Woods J. Effect of hospital in the home treatment on physical and cognitive function: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(8):1035–1038. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.8.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montalto M. The 500-bed hospital that isn’t there: the Victorian Department of Health review of the Hospital in the Home program. Med J Aust. 2010;193(10):598–601. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb04070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, Bair-Merritt MH. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5):439–445.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raîche M, Hébert R, Dubois M-F. PRISMA-7: a case-finding tool to identify older adults with moderate to severe disabilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005;65(4):559–564. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ader DN. Developing the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(Suppl 1):S1–S2. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000260537.45076.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng Y-S, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agmon M, Zisberg A, Gil E, Rand D, Gur-Yaish N, Azriel M. Association between 900 steps a day and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):272. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkinson C. The picker patient experience questionnaire: development and validation using data from in-patient surveys in five countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(5):353–358. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng J, Montalto M, Leff B. Hospital at home. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25(1):79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Purdey S, Huntley A. Predicting and preventing avoidable hospital admissions: a review. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2013;43(4):340–344. doi: 10.4997/jrcpe.2013.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aimonino Ricauda N, Tibaldi V, Leff B, et al. Substitutive “hospital at home” versus inpatient care for elderly patients with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(3):493–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caplan GA, Ward JA, Brennan NJ, Coconis J, Board N, Brown A. Hospital in the home: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 1999;170(4):156–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 31 kb)