Abstract

In this study several investigations and tests were performed to determine the antioxidant activity and the acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory potential of Pulmonaria officinalis and Centarium umbellatum aqueous extracts (10% mass) and ethanolic extracts (10% mass and 70% ethanol), respectively. Moreover, for each type of the prepared extracts of P. officinalis and of C. umbellatum the content in the biologically active compounds – polyphenols, flavones and proanthocyanidins was determined. The antioxidant activity was assessed using two methods, namely the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay and reducing power assay. The analyzed plant extracts showed a high acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory activity in the range of 72.24–94.24% (at the highest used dose – 3 mg/mL), 66.96% and 94.03% (at 3 mg/mL), respectively correlated with a high DPPH radical inhibition – 70.29–84.9% (at 3 mg/mL). These medicinal plants could provide a potential natural source of bioactive compounds and could be beneficial to the human health, especially in the neurodegenerative disorders and as sources of natural antioxidants in food industry.

Keywords: Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity, Tyrosinase inhibitory activity, Antioxidant activity, Pulmonaria officinalis and Centarium umbellatum

1. Introduction

Plants are an overall source of antioxidant activity compounds, such as phenolic acids, flavonoids (including anthocyanins and tannins), vitamins and carotenoids that may be used as pharmacologically active products (López et al., 2007).

Acetylcholinesterase enzyme (AChE, EC 3.1.1.7) plays a major role in the activity of the central (CNS) and peripheral (PNS) nervous systems, because it catalyzes the hydrolysis of the acetylcholine neurotransmitter, thus producing choline and acetate (ACh) (Legay, 2000). Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disorder with a still unclear pathogenesis. One of the most accepted theories has been ‘‘cholinergic hypothesis”, so inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) preserves the levels of acetylcholine and improves the cholinergic function and therefore has become the standard approach in the symptomatic treatment of AD (Houghton and Howes, 2005, Vinutha et al., 2007). To date, several plants have been identified as containing acetylcholinesterase inhibitory (AChEI) activity (Adewusi et al., 2011, Adewusi et al., 2010, Fale et al., 2012, Ferreira et al., 2006).

Earlier reports have revealed that oxidative injury plays the main role in the pathogenesis of plentiful neurodegenerative diseases including stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, etc. (Senol et al., 2010).

Antioxidant activity is one of the most important properties of plant extracts, because scientists have looked for sources of natural antioxidants to be introduced in many cosmetic, pharmaceutical and food formulations. The research for the new sources of antioxidants in the past resulted in the extensive studies on medicinal plants (Malinowska, 2013).

Tyrosinase (EC 1.14.18.1) is a copper enzyme that is essential in melanin biosynthesis and it was also admitted to play complex roles in human organisms, than previously thought. Furthermore, the role of tyrosinase in neuromelanin production and damage of the neurons related to Parkinson’s disease has been extensively studied (Greggio et al., 2005). These new findings emphasize the importance of tyrosinase inhibitor’s discovery and development.

Pulmonaria officinalis (lungwort) is an herbaceous perennial plant belonging to the family Boraginaceae, widely spread in Europe, with therapeutic use in bronchitis, laryngitis, kidney and respiratory diseases as well in gastric and duodenal ulcers (Dumitru and Răducanu, 1992). The plant contains unsaturated pyrrolizidine alkaloids, therefore it is not recommended for long-term consumption (Lüthy et al., 1984).

Centarium umbellatum (common centaury) is a medicinal plant from Gentianaceae family and it has been used as a medicinal herb for over 2000 years for its bitterness as an amarum, digestive and also for treating febrile conditions, diabetes, hepatitis and gout (Tucakov, 1990). It is also known as a hypothesive, anti-spasmodic, sedative and diuretic plant (Mounsif et al., 2000).

In this study, the anti-acetylcholinesterase, anti-tyrosinase and antioxidant activity of some aqueous and ethanolic extracts prepared from two Romanian medicinal plants: P. officinalis and C. umbellatum were determined. Moreover, the total polyphenol content, flavone and proanthocyanidin content was assessed, highlighting the correlation between the values determined for these biologically active compounds and the values of acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibition, and those of antioxidant activity, as well. The aim of this study was to find new sources of anti-acetylcholinesterase and anti-tyrosinase inhibitors, useful in treating neurodegenerative diseases and also sources of natural antioxidants.

2. Methodology

2.1. Materials

Aluminum chloride ⩾99%, Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent, potassium ferricyanide ⩾99%, trichloroacetic acid ⩾99%, ethanol and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), acetylcholinesterase from Electrophorus electricus (electric eel) (518 units/mg solid), 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) ⩾99%, acetylthiocholine iodide (AChl) ⩾99%, 3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-l-alanine (l-DOPA)⩾98%, tyrosinase from mushroom (1881 units/mg solid) and all solvents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (Sigma Aldrich, Germany), Fluka (Switzerland), Roth (Carl Roth GmbH, Germany) and distilled water was used for all the performed analyses (Millipore, Bedford, MA).

2.2. Preparation of the extracts

The plant material was purchased from a national producer (Fares Orastie) of herbal infusions in dry and already packed forms, supplied to supermarkets, drug stores and herbal shops. The aqueous extracts (10% mass) were obtained in 60 °C distilled water. Both aqueous and ethanolic extracts (10% mass and 70% ethanol) were subjected to ultrasound at room temperature, for 1 h, followed by filtration.

2.3. Determination of polyphenols content

Determination of polyphenol content was made using Folin–Ciocalteu method (Singleton et al., 1999). The polyphenol content was expressed in gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/mL of extract.

2.4. Determination of flavone content

Determination of flavone content was analyzed using aluminum chloride colorimetric method (Lin and Tang, 2007). The flavone content was expressed in μg rutin equivalent (RE)/mL of extract.

2.5. Determination of proanthocyanidins

Determination of proanthocyanidins was carried out using the vanillin assay in glacial acetic acid (Butler et al., 1982), with slight modifications. The absorbance was read at 500 nm. The results were expressed as catechin equivalents (CE)/mL of extract.

2.6. Antioxidant assays

The antioxidant activity was measured using 2 methods:

2.6.1. DPPH radical scavenging activity

The scavenging activity on the DPPH radical was determined by measuring the decrease in the DPPH maximum absorbance at 517 nm after 3 min (Bondet et al., 1997). The percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity of the samples was calculated as follows:

where AB = control absorbance and AA = sample absorbance.

2.6.2. Reducing power activity

The reducing power activity was determined according to a previously described procedure (Berker et al., 2007). Sample extracts (0.1 mL) were mixed with 2.5 mL of 200 mM/L sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 2.5 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide. The mixture was intensively shaken, then incubated at 50 °C for 20 min. In the next step, 2.5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (w/v) was added and the resulted mixture was mixed with 2.5 mL deionized water and 0.5 mL of 0.1% ferric chloride. The absorbance was spectrophotometrically measured at 700 nm.

2.7. HPLC analysis

The chromatographic measurements were performed into a complete HPLC SHIMADZU system, using a Nucleosil 100-3.5 C18 column, KROMASIL, 100 × 2.1 mm. The system was coupled to a MS detector, LCMS-2010 detector (liquid chromatograph mass spectrometer), equipped with an ESI interface. The mobile phase was sonicated in order to eliminate the dissolved air, then filtrated through a PTFE 0.2 μm membrane. The method used for measuring polyphenols was published by Alecu et al. (2015).

The mobile phase consists of formic acid (to improve ionization and resolution) in water (pH = 3.0) as solvent A and formic acid in acetonitrile (pH = 3.0) as solvent B. The polyphenolic compounds separation was performed using binary gradient elution: 0 min 5% solvent B; 0.01–20 min 5–30% solvent B; 20–40 min 30% solvent B; 40.01–50 min 30–50% solvent B; 50.01–52 min 50–5% solvent B. The flow rate was: 0–5 min 0.1 mL min−1; 5.01–15 min 0.2 mL min−1; 15.01–35 min 0.1 mL min−1; 35.01–50 min 0.2 mL min−1; 50–52 min 0.1 mL min−1.

2.8. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity

The acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity was measured using the method described by Ingkaninan et al. (2003). Briefly, 3 mL of 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 100 μL of sample solution at different concentrations (3 mg/mL, 1.5 mg/mL, 0.75 mg/mL) and 20 μL AChE (6 U/mL) solution were mixed and incubated for 15 min at 30 °C; a 50 μL volume of 3 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) was added to this mixture. The reaction was then initiated by the addition of 50 μL of 15 mM acetylthiocholine iodide (AChl). The hydrolysis of this substrate was monitored at precisely 405 nm wavelength. At this wavelength the formation of yellow 5-thio-2-nitrobenzoate anion was noticed as the result of the reaction of DTNB with thiocholine, released by the enzymatic hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine iodide.

The enzymatic activity was calculated as a percentage of the velocities compared to that of the assay using buffer instead of inhibitor (extract), based on the formula:

where E is the activity of the enzyme without test sample and S the activity of the enzyme with test sample.

2.9. Tyrosinase inhibition assay

The tyrosinase (EC1.14.1.8.1, Sigma) activity was spectrophotometrically measured using 3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-l-alanine (l-DOPA) as substrate (Liang et al., 2012). Tyrosinase aqueous solution (100 μL, 0.5 mg/mL), plant extract (100 μL, 50 μL, 25 μL) and 1850 μL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) were mixed and incubated for 15 min at 30 °C. Next, 10 mM l-DOPA solution (50 μL) was added and the absorbance at 475 nm was measured for 3 min. The same reaction mixture having the plant extract replaced by the equivalent amount of phosphate buffer, served as blank. The percentage inhibition of tyrosinase activity was calculated as follows:

where ΔAcontrol is the change of absorbance at 475 nm without a test sample, and ΔAsample is the change of absorbance at 475 nm with a test sample.

2.10. Statistical analysis

The tests were carried out in triplicate and the software Microsoft Office Excel 2007 was used for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the one-tailed paired Student’s test, on each pair of interest. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. The determination of total polyphenolic, flavone and proanthocyanidin contents

The total polyphenol, proanthocyanidin and flavone contents from the analyzed extracts are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Compounds content (polyphenols, flavones, proanthocyanidins) from the tested extracts.

| Sample | Polyphenols (μg GAE/ mL) | Proanthocyanidins (μg CE/mL) | Flavones (μg RE/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonaria officinalis (lungwort) | Aqueous extract (10% mass) | 486.60 ± 2.12 | 41.83 ± 3.25 | 104.28 ± 3.25 |

| 70% ethanolic extract (10% mass) | 576.62 ± 6.32 | 61.5 ± 6.23 | 272.81 ± 9.21 | |

| Centarium umbellatum (common centaury) | Aqueous extract (10% mass) | 560.11 ± 8.59 | 43 ± 5.23 | 160.75 ± 5.12 |

| 70% ethanolic extract (10% mass) | 656.61 ± 7.56 | 63.33 ± 2.63 | 496.28 ± 8.91 | |

One can see that the polyphenols and the proanthocyanidins are in similar amounts in both studied plants, higher amounts in ethanolic extracts than in aqueous and somewhat higher in C. umbellatum extracts than in P. officinalis extracts. The analyzed extracts showed higher flavones content especially in ethanolic extracts, the highest value being found in C. umbellatum ethanolic extract −496.28 μg RE/mL rutin.

The flavonoids constitute a prominent group of secondary metabolites in these plants that may possess biological activity and have beneficial effects on human health as antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, anti-cholesterolemic, antioxidant and anti-cancer agents (Abirami et al., 2014).

P. officinalis was revealed to possess a high amount of polyphenols (and an increased antioxidant activity (Ivanova et al., 2005). Literature related to the preliminary screening of antioxidant activity for the P. officinalis isolated extracts used in cosmetics industry showed a high value for antioxidant activity that could be correlated to the high content of the flavonoids (Malinowska, 2013).

3.2. Antioxidant activity determination

3.2.1. DPPH radical scavenging activity

The DPPH free radical is a stable free radical, that has been widely accepted as a tool for estimating the free radical-scavenging activity of antioxidant (Nagai et al., 2003). In the DPPH test, the antioxidants were able to reduce the stable DPPH radical to the yellow-colored diphenylpicryhydrazine. The effect of antioxidant on DPPH radical scavenging was conceived to their hydrogen-donating ability (Chen et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2011).

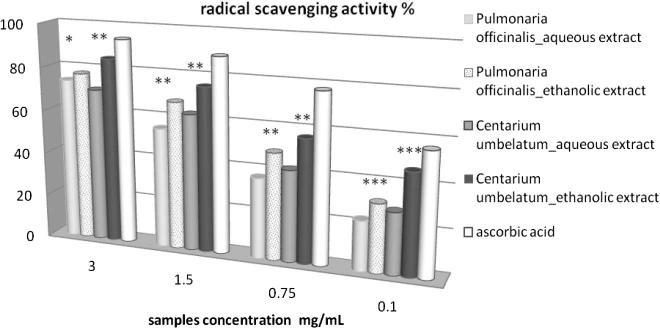

Significant correlation (p < 0.05) was found between antioxidant activity (determined by DPPH, and reducing power) and total polyhenol and flavone contents, indicating considerable contribution of these compounds to the total antioxidant activity observed for these plant extracts. This result is also supported by some previous reports (Malinowska, 2013, Jacobo-Velazquez and Cisneros-Zevallos, 2009). Thus, the extracts with the highest flavone contents were also proved to have the highest antioxidant activity, in both of the used methods. Therefore, by DPPH assay Centarium umbellatum ethanolic extract was found to have the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity value – 84.9% (at 3 mg/mL) and determinations developed on it also revealed the highest flavone content – 496.28 ± 8.91 μg RE/mL. In the case of P. officinalis ethanolic extract the DPPH radical scavenging activity value was found to be of 75.47% (at 3 mg/mL), which also showed a high content of flavones – 272.8 ± 9.21 μg RE/mL. The ethanolic plant extracts proved an increased inhibition activity on the DPPH free radical, than the aqueous plant extracts. The DPPH radical scavenging activity percent decrease proportionally with the concentration of the analyzed sample (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Radical scavenging activity % p < 0.05 compared the activity of the ethanolic extracts with that of the aqueous extracts ∗∗p < 0.01 compared the activity of the ethanolic extracts with that of the aqueous extracts; ∗∗∗p < 0.001 compared the activity of the ethanolic extracts with that of the aqueous extracts; ∗p < 0.05 compared polyphenol content of extracts with radical scavenging activity; ∗p < 0.05 compared flavone content of extracts with radical scavenging activity.

Flavonoid and phenolic acids have been intensively studied for their free radical scavenging and antioxidant properties. Flavonoids are reported to possess strong free radical scavenging activities based on their ability to act as hydrogen or electron donors and chelate transition metals (Le et al., 2007). Antioxidant properties of phenolic compounds are directly linked to their structure. Phenolics contain at least one aromatic ring bearing one or more hydroxyl groups and are therefore able to quench free radicals by forming resonance-stabilized phenoxyl radicals (Siler et al., 2014).

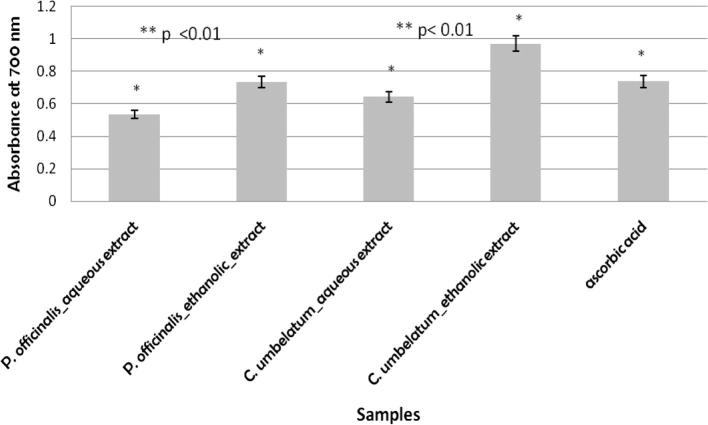

3.2.2. Reducing power activity

In this assay, the Fe3+–Fe2+ transformation in the presence of the extracts was assessed. The reducing power of extracts and ascorbic acid, used as reference compound, were assayed and the results are shown in Fig. 2. Aqueous extracts have showed lower reducing power activity than ascorbic acid. In our work a correlation between reducing power activity of extracts and polyphenol and flavone content of them can be observed as in other studies (Kim et al., 2008, Malheiro et al., 2012).

Figure 2.

Reducing power of Pulmonaria officinalis and Centarium umbellatum and aqueous and ethanolic extracts ∗p < 0.05 compared polyphenol content of extracts with reducing power ∗p < 0.05 compared flavone content of extracts with reducing power ∗∗p < 0.01 compared the activity of the ethanolic extracts with that of the aqueous extracts.

The obtained results for antioxidant activity determination by reducing power method are correlated with the results obtained by the DPPH method. Thus, most pronounced antioxidant activity was observed in the C. umbellatum ethanolic extract followed by P. officinalis ethanolic extract, as can be seen in Fig. 2. The other results demonstrated that Centaurium erythraea leaf extract exhibited high antioxidant capacity correlated with a high proanthocyanidin levels (Sefia et al., 2011).

3.3. HPLC analysis

The HPLC–MS method has been applied for the evaluation of polyphenolic profiles in the case of different plant extract samples. Using the SIM mode (selected ion monitoring) the corresponding peaks of gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, rutin, sinapic acid, hyperoside, ferulic acid, naringin, hesperidin, rosmarinic acid, myricetin, luteolin, quercetin, apigenin, kaempferol and isorhamnetin fragment ions were obtained.

Under the optimum chromatographic conditions the compounds of interest were fairly resolved. Values for polyphenolic compounds in samples of plant extracts obtained with this method are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

HPLC–MS values of polyphenol compounds in plant extracts.

| Compound [M/z]-name | Pulmonaria officinalis L. water (μg/mL) | Pulmonaria officinalis L. 70% ethanol (μg/mL) | Centarium umbellatum water (μg/mL) | Centarium umbellatum 70% ethanol (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin 301 | − | + | 0.35 | − |

| Rutin 609 | 0.20 | 8.76 | 11.08 | 14.09 |

| Kaempferol 285 | + | + | + | + |

| Isorhamnetin 315 | − | + | + | + |

| Naringin 579 | − | − | + | − |

| Hyperoside 463 | 0.54 | 3.97 | 0.66 | 2.26 |

| Gallic acid 169 | 0.97 | − | 1.07 | − |

| Syringic acid 197 | − | − | 45.96 | 16.11 |

| p-Coumaric acid 163 | 0.46 | − | 0.95 | − |

| Caffeic acid 179 | 12.94 | 3.36 | 8.03 | + |

| Ferulic acid 193 | + | − | 0.31 | − |

| Rosmarinic acid 359 | 41.94 | 124.59 | 2.99 | 2.71 |

| Chlorogenic acid 353 | 3.53 | 3.03 | 11.99 | 12.53 |

| Luteolin 285 | − | + | + | + |

| Apigenin 269 | − | + | + | + |

− under the limit of detection; + under the limit of quantification.

The P. officinalis ethanolic extract contains high concentrations of the rosmarinic acid (124.59 μg/mL), hyperoside and rutin and P. officinalis aqueous extract contains caffeic acid (12.94 μg/mL). The C. umbellatum aqueous extract contains high contents of syringic acid (45.96 μg/mL) and caffeic acid, whereas chlorogenic and rosmarinic acids are in similar amounts in both extracts. Rutin and hyperoside were proved to be present in great amounts in C. umbellatum ethanolic extract.

The method was applied to C. umbellatum extracts, using the SCAN mode for the identification of polyphenols and erythrocentaurin, trihydroxyxanthone, 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxyxanthone, p-coumaroylquinic acid, oleanolic acid and sakuranin. Previous studies have identified a number of different xanthones and xanthone glycosides in the members of genus Centarium (Valentao et al., 2001, Ross et al., 2011). Phytochemical studies of centauries revealed the presence of phenolics (xanthones, phenolic acids and their derivatives) as main constituents (Valentao et al., 2001). The main phenolic compounds from C. erythraea were several esters of hydroxycinnamic acids, namely p-coumaric, ferulic and sinapic acids (Valentao et al., 2001), while the phenolic compounds developed in P. officinalis extracts were quercetin and kaempferol (Malinowska, 2013).

3.4. Acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibition activity

Herbal medicines have been used for improving cognitive functions and for the treatment of memory loss. Our study investigates enzyme inhibitory potential of two medicinal plants from Romania – P. officinalis and C. umbellatum – for which there are no data in the literature at present. The obtained results regarding the acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory activity of these plant aqueous and ethanolic extracts are presented in the Table 3, Table 4. The results are similar for the two tested plant extracts. The ethanolic extracts exhibit acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory activity more pronounced than the aqueous extracts, the inhibition values being >70% for the samples’ highest concentration (3 mg/mL). The highest inhibition value was obtained for the C. umbellatum ethanolic extract (94.24% – AChE inhibition and 74.39% – tyrosinase inhibition) and the highest content of flavones 496.28 ± 8.91 μg RE/mL was also determined in the same extract. The highest inhibition of the ethanolic extract could be due to the presence of high contents of flavone.

Table 3.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of extracts.

| Sample | AChE inhibition % |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mg/mL | 1.5 mg/mL | 0.75 mg/mL | ||

| Pulmonaria officinalis | Aqueous extract (10% mass) | 72.24 ± 7.12 ⁎ | 62.12 ± 6.23⁎ | 43.61 ± 2.57⁎ |

| 70% ethanolic extract (10% mass) | 87.72 ± 2.35 ⁎ | 69.21 ± 3.56 ⁎ | 50.70 ± 6.54⁎ | |

| Centarium umbellatum | Aqueous extract (10% mass) | 92.28 ± 7.24⁎ | 70.21 ± 6.28⁎ | 58.85 ± 6.89⁎ |

| 70% ethanolic extract (10% mass) | 94.24 ± 6.35⁎ | 72.36 ± 6.25⁎ | 64.27 ± 5.59⁎ | |

| Galanthamine | – | – | 99.98 ± 2.02 | |

| Caffeic acid | – | 62.67 ± 7.32 | 42.19 ± 6.57 | |

| Rosmarinic acid | – | 52.89 ± 6.93 | 30.64 ± 5.46 | |

| Rutin | – | 59.46 ± 3.65 | 31.23 ± 2.57 | |

| Chlorogenic acid | – | 75.34 ± 2.39 | 54.11 ± 5.24 | |

Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples of three independent experiments.

p < 0.05, compared the activity of the ethanolic extracts with that of the aqueous extracts.

Table 4.

Tyrosinase inhibitory activities of extracts.

| Sample | Tyrosinase inhibition % |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mg/mL | 1.5 mg/mL | 0.75 mg/mL | ||

| Pulmonaria officinalis | Aqueous extract (10% mass) | 56.96 ± 5.21⁎ | 43.62 ± 6.23⁎ | 30.56 ± 6.56⁎ |

| 70% ethanolic extract (10% mass) | 71.69 ± 8.23⁎ | 59.36 ± 3.56⁎ | 46.52 ± 3.23⁎ | |

| Centarium umbellatum | Aqueous extract (10% mass) | 69.05 ± 6.63⁎ | 46.21 ± 6.28⁎ | 38.76 ± 5.67⁎ |

| 70% ethanolic extract (10% mass) | 74.39 ± 7.89⁎ | 65.36 ± 3.64⁎ | 54.36 ± 4.36⁎ | |

| Kojic acid | 98.7 ± 4.23 | 94.2 ± 2.87 | 89.7 ± 5.24 | |

| Ellagic acid | – | 45.77 ± 1.71 | 25.42 ± 1.52 | |

| Quercetin | – | 62.60 ± 3.65 | 33.45 ± 2.59 | |

| Chlorogenic acid | – | 58.09 ± 2.31 | 41.45 ± 2.83 | |

| Rutin | – | 47.23 ± 6.54 | 32.30 ± 1.37 | |

Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples of three independent experiments.

p < 0.05, compared the activity of the ethanolic extracts with that of the aqueous extracts.

Present in large amounts in the two studied plants flavonoids have miscellaneous favorable, biochemical, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, anti-cancer, anti-genotoxic activity as well (Castañeda-Ovando et al., 2009). There are few reports on acetylcholinesterase/butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of flavonoids, assigned as the main strategy for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. On the other hand, flavonoids as polyphenolic substances have been known for their strong antioxidant activity, a major factor for the AD treatment (Tareq et al., 2009).

Polyphenols are responsible for reducing the incidence of certain age related neurological disorders including macular degeneration and dementia (Bastianetto et al., 2000). Rosmarinic acid present in high amounts in P. officinalis extracts and in lower amounts in C. umbellatum extracts, explains their antioxidant activity and acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity (Fale et al., 2009). Present in large amounts in aqueous extracts from both studied plants caffeic acid acts as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumor and anti-metastatic agent (Chung et al., 2004). Chlorogenic acid and rutin, both identified in C. umbellatum extracts, develop anti-oxidative activities associated with free radical scavenging (Almeida et al., 2009). Syringic acid – present in C. umbellatum extracts – has strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects (Levites et al., 2001), and it was found to exert neuroprotective effect by inhibiting oxidative stress. Thus syringic acid improves behavioral dysfunctions in a mouse model of Parkinson disease (Rekha et al., 2014).

4. Conclusions

In this study two medicinal plants from Romania, P. officinalis and C. umbellatum were evaluated – for first time – for their acetylcholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory effects, as well as for their antioxidant activity. The phytochemical analysis of extracts has showed high contents of biologically active compounds: polyphenols, flavones, proanthocyanidins, compounds that give antioxidant and antiradical properties of plants and probably, potential inhibitor on enzymes studied. So, the C. umbellatum extracts showed the high acetylcholinesterase inhibitory effects – 94.24%, high tyrosinase inhibitory effects – 94.03%, and high antioxidant activities 84.9% DPPH radical scavenging activity, as well as high flavone content. The P. officinalis extracts showed slightly lower acetylcholinesterase inhibitory effects – 87.7%, tyrosinase inhibitory effects – 73.69%, antioxidant activities – 75.47% DPPH radical scavenging activity, also corresponding to lower flavone content. Based on these presented data, our study suggests that these medicinal plants are promising candidates useful for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia, Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease. The two tested medicinal plants are great sources of natural antioxidants for food industry.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Romanian National Center for Program Management – PN 09-360101/2012 project.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abirami A., Nagarani G., Siddhuraju P. In vitro antioxidant, anti-diabetic, cholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory potential of fresh juice from Citrus hystrix and C. maxima fruits. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2014;3:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Adewusi A.E.B., Moodley N., Steenkamp V. Medicinal plants with cholinesterase inhibitory activity: a review. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010;9:8257–8276. [Google Scholar]

- Adewusi A.E.A., Steenkamp V. In vitro screening for acetylcholinesterase inhibition and antioxidant activity of medicinal plants from southern Africa. Asia Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011;4:829–835. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alecu A., Albu C., Litescu S.C., Eremia S.A.V., Radu G.L. Phenolic and anthocyanin profile of Valea calugareasca red wines by HPLC–PDA–MS and MALDI–TOF analysis. Food Anal. Methods. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Almeida I.F., Fernandes E., Lima J.L., Valentao P., Andrade P.B., Seabra R.M., Costa P.C., Bahia M.F. Oxygen and nitrogen reactive species are effectively scavenged by Eucalyptus globulus leaf water extract. J. Med. Food. 2009;12:175–183. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2008.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastianetto S., Zheng W.-H., Quirion R. Involvement of its flavonoid constituents and protein kinase C the Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) protects and rescues hippocampal cells against nitric oxide-induced toxicity. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:2268–2277. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berker K., Guclu K., Tor I., Apak R. Comparative evaluation of Fe(III) reducing power-based antioxidant capacity assays in the presence of phenanthroline, batho-phenanthroline, tripyridyltriazine (FRAP), and ferricyanide reagents. Talanta. 2007;72:1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondet V., Brand-Williams W., Berset C. Kinetics and mechanisms of antioxidant activity using the DPPH• free radical method. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 1997;30:609. [Google Scholar]

- Butler L.G., Price M.L. Vanilin assay for proanthocyanidins (condensed tannins) modification of the solvent for estimation of the degree of polymerization. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1982;30:1087–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda-Ovando A., Pacheco-Hernández D., Páez-Hernández E., Rodríguez J.A., Galán Vidal C.A. Chemical studies of anthocyanins: a review. Food Chem. 2009;113:859–871. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Xie M.Y., Nie S.P., Li C., Wang Y.X. Purification, composition analysis and antioxidant activity of a polysaccharide from the fruiting bodies of Ganoderma atrum. Food Chem. 2008;107:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chung T.W., Moon S.K., Chang Y.C., Ko J.H., Lee Y.C., Cho G., Kim S.H., Kim J.G., Kim C.H. Novel and therapeutic effect of caffeic acid and caffeic acid phenyl ester on hepatocarcinoma cells: complete regression of hepatoma growth and metastasis by dual mechanism. FASEB J. 2004;18:1670–1681. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2126com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitru E., Răducanu D. Ed. Stiintifică; Bucuresti: 1992. Terapie naturistă. [Google Scholar]

- Fale P.L.B., Borges C., Madeira P.J.A., Ascensão L., Eduarda M., Araújo M., Florêncio M.H., Serralheiro M.L.M. Rosmarinic acid, scutellarein 4′-methyl ether 7-O-glucuronide and (16S)-coleon E are the main compounds responsible for the antiacetylcholinesterase and antioxidant activity in herbal tea of Plectranthus barbatus (“falso boldo”) Food Chem. 2009;114:798–805. [Google Scholar]

- Fale P.L.A., Amaral F., Amorim Madeira P.J., Sousa Silva M., Florencio M.H., Frazao F.N., Serralheiro M.L.M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition, antioxidant activity and toxicity of Peumus boldus water extracts on HeLa and CaCo-2 cell lines. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:2656–2662. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A., Proenc C., Serralheiro M.L.M., Araujo M.E.M. The in vitro screening for acetylcholinesterase inhibition and antioxidant activity of medicinal plants from Portugal. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;108:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E., Bergantino E., Carter D., Ahmad R., Costin G.E., Hearing V.J., Clarimon J., Singleton A., Eerola J., Hellstrom O., Tienari P.J., Miller D.W., Beilina A., Bubacco L., Cookson M.R. Tyrosinase exacerbates dopamine toxicity but is not genetically associated with Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:246–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton P.J., Howes M.J. Natural products and derivatives affecting neurotransmission relevant to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Neurosignals. 2005;14:6–22. doi: 10.1159/000085382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingkaninan K., Temkitthawon P., Chuenchon K., Yuyaem T., Thongnoi W. Screening for acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity in plants used in Thai traditional rejuvenating and neurotonic remedies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003;89:261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova D., Gerova D., Chervenkov T., Yankova T. Polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of Bulgarian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;96:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo-Velazquez D.A., Cisneros-Zevallos L. Correlations of antioxidant activity against phenolic content revisited: a new approach in data analysis for food and medicinal plant. J. Food Sci. 2009;74:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M.Y., Seguin P., Ahn J.K., Kim J.J., Chun S.C., Kim E.H., Seo S.H., Kang E.Y., Kim S.L., Park Y.J., Ro H.M., Chung I.M. Phenolic compound concentration and antioxidant activities of edible and medicinal mushrooms from Korea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:7265–7270. doi: 10.1021/jf8008553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le K., Chiu F., Ng K. Identification and quantification of antioxidants in Fructus lycii. Food Chem. 2007;105:353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Legay C. Why so many forms of acetylcholinesterases? Microsc. Res. Tech. 2000;49:56–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000401)49:1<56::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levites Y., Weinreb O., Maor G., Youdim M.B., Mandel S. Green tea polyphenol (l)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents, N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6 tetrahydropyridine – induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration. J. Neurochem. 2001;78:1073–1082. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Lim J.H., Kim S.H., Kim D.S. Dioscin: a synergistic tyrosinase inhibitor from the roots of Smilax China. Food Chem. 2012;134:1146. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.Y., Tang C.Y. Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid contents in selected fruits and vegetables, as well as their stimulatory effects on mouse splenocyte proliferation. Food Chem. 2007;101:140–147. [Google Scholar]

- López V., Akerreta S., Casanova E., García-Mina J.M., Cavero R.Y., Calvo M.I. In vitro antioxidant and anti-rhizopus activities of Lamiaceae herbal extracts. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2007;62:151–155. doi: 10.1007/s11130-007-0056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüthy J., Brauchli J., Zweifel U., Schmid P., Schlatter C. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids in medicinal plants of Boraginaceal: Borago officinalis L. and Pulmonaria officinalis L. Pharm. Acta Helv. 1984;59:242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malheiro R., Sa O., Pereira E., Aguiar C., Baptista P., Pereira J.A. Arbutus unedo L. leaves as source of phytochemicals with bioactive properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012;37:473–478. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowska P. Effect of flavonoids content on antioxidant activity of commercial cosmetic plant extracts. Herb Pol. 2013;59:63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mounsif H., Liliane L., Jean B.M., Badiaa L. Experimental diuretic effects of Rosmarinus offfcinalis and Centaurium erythraea. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000;71:465–472. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(00)00184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T., Inoue R., Inoue H., Suzuki N. Preparation and antioxidant properties of water extract of propolis. Food Chem. 2003;80:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rekha K.R., Selvakumarb G.P., Sivakamasundaria R.I. Effects of syringic acid on chronic MPTP/probenecid induced motor dysfunction, dopaminergic markers expression and neuroinflammation in C57BL/6 mice. Biomed. Aging Pathol. 2014;4:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ross S.A., El-Shanawany A., Mohamed G.A., Nafady A.M., Ibrahim S.R., Radwan M.M. Antifungal activity of xanthones from Centaurium spicatum (Gentianaceae) Planta Med. 2011;77:43. [Google Scholar]

- Sefia M., Fetouia H., Lachkara N., Tahraouib A., Lyoussib B., Boudawarac T., Zeghala N. Centaurium erythrea (Gentianaceae) leaf extract alleviates streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress and -cell damage in rat pancreas. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;135:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senol F.S., Orhan I., Yilmaz G., Cicek M., Sener B. Acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, and tyrosinase inhibition studies and antioxidant activities of 33 Scutellaria L. taxa from Turkey. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010;48:781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siler B., Zivkovic S., Banjanac T., Cvetkovic J., Nestorovic Zivkovic J., Ciric A., Sokovic M., Mišic D. Centauries as underestimated food additives: antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. Food Chem. 2014;147:367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton V.L., Orthofer R., Lamuela-Raventos R.M. Methods Enzymol. 1999;299:152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Tareq M., Khan H., Orhan I., Şenol F.S., Kartal M., Şener B., Dvorská M., Šmejkal K., Slapetova T. Cholinesterase inhibitory activities of some flavonoid derivatives and chosen xanthone and their molecular docking studies. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009;181:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucakov, J., 1990. Healing with plants – phytotherapy. Rad, Belgrade (Serbian).

- Valentao P., Fernandes E., Carvalho F., Andrade P.B., Seabra R.M., Bastos M.L. Antioxidant activity of Centaurium erythraea infusion evidenced by its superoxide radical scavenging and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:3476–3479. doi: 10.1021/jf001145s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinutha B., Prashanth D., Salma K., Sreeja S.L., Pratiti D., Padmaja R., Radhika S., Amit A., Venkateshwarlu K., Deepak M. Screening of selected Indian medicinal plants for acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;109:359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., He L., Hu M. Optimized ultrasonic-assisted extraction of flavonoids from Prunella vulgaris L. and evaluation of antioxidant activities in vitro. Innovation Food Sci. Emerg. 2011;12:18–25. [Google Scholar]