Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death from infectious disease, and the current vaccine, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), is inadequate. Nanoparticles (NPs) are an emerging vaccine technology, with recent successes in oncology and infectious diseases. NPs have been exploited as antigen delivery systems and also for their adjuvantic properties. However, the mechanisms underlying their immunological activity remain obscure. Here, we developed a novel mucosal TB vaccine (Nano-FP1) based upon yellow carnauba wax NPs (YC-NPs), coated with a fusion protein consisting of three Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) antigens: Acr, Ag85B, and HBHA. Mucosal immunization of BCG-primed mice with Nano-FP1 significantly enhanced protection in animals challenged with low-dose, aerosolized Mtb. Bacterial control by Nano-FP1 was associated with dramatically enhanced cellular immunity compared to BCG, including superior CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation, tissue-resident memory T cell (Trm) seeding in the lungs, and cytokine polyfunctionality. Alongside these effects, we also observed potent humoral responses, such as the generation of Ag85B-specific serum IgG and respiratory IgA. Finally, we found that YC-NPs were able to activate antigen-presenting cells via an unconventional IRF-3-associated activation signature, without the production of potentially harmful inflammatory mediators, providing a mechanistic framework for vaccine efficacy and future development.

Keywords: vaccines, nanoparticles, tuberculosis, adjuvant, antigen-presenting cells, immunity

In this issue of Molecular Therapy, Hart and colleagues describe a new vaccine candidate for tuberculosis based on multi-antigen fusion protein-coated nanoparticles. The work showed that mucosal boosting of systemic BCG induced superior immunity and conferred greater protection in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice than BCG alone. This new vaccine candidate, therefore, merits further development as a potential BCG-boost vaccine against tuberculosis.

Introduction

As of 2017, tuberculosis (TB) is the deadliest infectious disease worldwide,1 killing 1.8 million people annually, with an associated economic impact in the region of $12 billion.2 The outlook for the control and management of TB is mixed. For the first time in recent years, two new drugs, bedaquiline and delamanid, have been licensed,3 and newer, more effective, treatment regimens are coming to the fore.4, 5 Despite these innovations, deficits in TB control programs and the challenge of antibiotic resistance mean that there has been little change in the overall incidence of TB in the past decade.6 Indeed, the 2025 World Health Organization (WHO) global TB targets are unlikely to be met, particularly in heavily affected countries such as China and India.6

The current vaccine for TB, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), is nearly a century old. While moderately effective in infants and adolescents, the protection it offers is highly variable and it is poorly effective in adults.7 The failure of MVA85A, one of only two vaccines to reach phase 2b clinical trials in recent years, illustrates the challenges remaining in TB vaccine development.8 Generation of an effective TB vaccine represents the only route to achieving long-term control or eradication of the disease.

Nanoparticles (NPs) are a nascent and attractive platform for vaccine development due to their low toxicity, ease of manufacturing, and low cost. Many NPs are able to act simultaneously as adjuvant and antigen delivery system,9 thereby conferring benefits absent in traditional antigen-adjuvant approaches. NPs are biochemically heterogeneous and may be composed of various synthetic (e.g., polystyrene) or natural (e.g., chitosan) compounds, with important variations in charge, size, and structure. The unique physiochemical composition of each type of NP dictates their immunological properties from affecting antigen uptake and diversion to lymphoid organs, to the induction of autophagy and activation of the inflammasome. Importantly for vaccines against intracellular pathogens, some NPs can facilitate the cross-presentation of antigen, thereby eliciting cytotoxic immune responses.10, 11 Given these benefits, NPs have played a significant role in advances within infectious disease vaccine development. Testament to their potential is the recent licensing of a landmark vaccine, Mosquirix, containing nanoparticulate-scale liposomes, which is the first-ever licensed malaria vaccine.12, 13

In the present study, we use NPs produced via the emulsification of yellow carnauba (YC) palm wax with sodium myristate (NaMA). YC wax and its derivatives are classified by the European Food Standards Agency as non-toxic, and their use is licensed in a wide range of edible and cosmetic products.14 These NPs have an average diameter of ∼400 nm (ranging from 200 to 800 nm) and are anionic, with a zeta potential of approximately −75 mV, thus imparting a high colloidal stability on YC-NaMA in suspension.15, 16 YC-NaMA NPs have shown considerable promise as a vaccine antigen delivery system, stimulating potent immune responses when being used to deliver the HIV-gp140 and TB Ag85B antigens in murine vaccine studies.15, 16 However, the mechanisms responsible for these effects remain undefined.

Here, we tested a novel TB vaccine (“Nano-FP1”) composed of YC-NaMA coated with a fusion protein (FP1) consisting of the Mtb antigens Ag85B (early expression), Acr (latent expression), and HBHA (epithelium targeting). The latter antigen comprised only the heparin-binding domain and was, therefore, included not as an immunogen but as a vaccine “guide” to epithelial tissue. We show that mucosal immunization with Nano-FP1 significantly enhances protection in BCG-primed, and also BCG-naive, mice, making it an appealing vaccine for immunocompromised individuals. This protection was associated with a breadth of antigen-specific cellular and humoral immune responses at both systemic and mucosal sites. Importantly, we demonstrate for the first time that YC-NPs induce a specific interferon regulatory factor (IRF)3-biased activation signature in antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that results in a phenotypically mature yet hypo-inflammatory phenotype, corresponding with muted nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activity and prolonged type I interferon (IFN) production. These data show that NPs derived from an abundant natural product can effectively mimic the function of expensive and highly developed synthetic adjuvants and that the mucosal vaccine Nano-FP1 can play a major role in preventing TB.

Results

Adsorption of FP1 onto YC-NPs

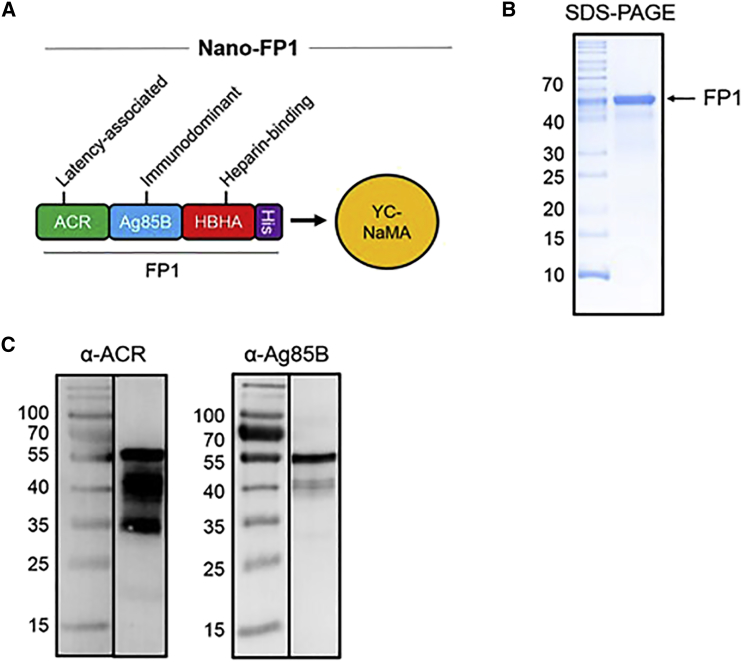

Effective carriage of antigen by YC-NaMA is integral to the success of this delivery system. Interaction of protein antigens with YC-NaMA is likely to occur, due to both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions17, 18 with the availability of hydrophobic or charged moieties on the surface of the NP and the osmolarity of the adsorption solution both playing a role in the efficiency of adsorption. First, a fusion protein (FP1; Figure 1A) was constructed that expressed three Mtb antigens with unique properties: Ag85B, a protective Th1-inducing and early-expressed antigen; Acr, an antigen expressed during latency; and a portion of HBHA, responsible for binding to host epithelium. FP1 was cloned and expressed in E. coli, followed by purification to over 97% (Figures 1B and 1C). Adsorption of FP1 onto YC-NaMA was required prior to immunization. Therefore, we tested whether FP1 bound to NPs under experimental conditions. To assess protein loading, the size of the NPs was measured pre- and post-adsorption. Moreover, after ultracentrifugation, we measured the amount of free FP1 in the supernatant, allowing quantification of the amount of bound protein. After adsorption, there was a significant increase in the mean size of YC-NaMA NPs from 324.4 ± 2.4 nm for naked NPs to 353.4 ± 3.5 nm after protein loading (paired t test, p = 0.03). Additionally, there was a significant increase in the zeta potential of the NPs from −85.3 ± 0.95 mV to −79.1 ± 1.6 mV (p = 0.003) after FP1 loading. Although size and zeta potential increased after protein loading, the polydispersity index (PDI) remained low (0.26), and the zeta potential remained strongly negative, indicating that FP1-loaded NPs retain high colloidial stability. After adsorption, NPs were separated from unbound FP1. Of the starting amount of 100 μg, ∼35 μg free FP1 was detected, indicating 65% ± 4.6% binding of FP1 to YC-NaMA NPs under experimental conditions.

Figure 1.

FP1 Composition and Loading onto Nanoparticles

(A–C) The Nano-FP1 vaccine consists of a fusion protein containing the Mtb antigens Acr, Ag85B, and HBHA adsorbed onto the surface of YC-NaMA nanoparticles (A). Purified FP1 was ∼55 kDa, as measured by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (B). Western blotting with specific antibody demonstrated the presence of the constituent antigens, Acr and Ag85B, within FP1 (C).

Nano-FP1 Protects against TB in BCG-Primed and BCG-Naive Animals

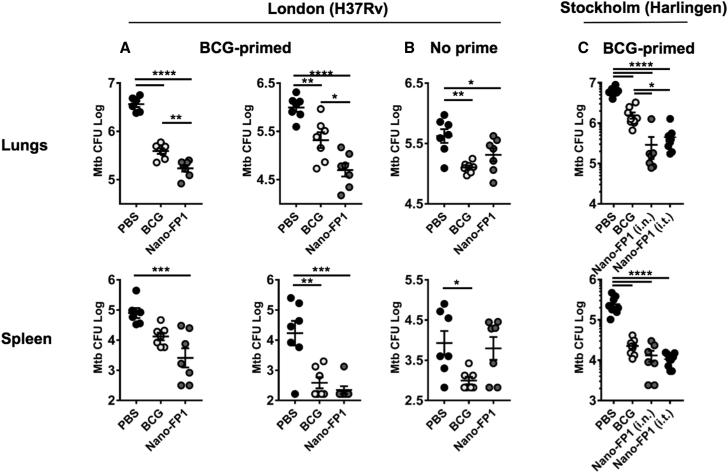

Next, FP1-loaded NPs (Nano-FP1) were tested for protective efficacy against two Mtb strains: Mtb H37Rv in London and Mtb Harlingen in Stockholm (Figure 2). Low-dose infection models are physiologically representative of natural infection, so we utilized aerosolization technology to challenge mice with Mtb. Mice were immunized via the intranasal or intratracheal (Stockholm only) routes (plus or minus subcutaneous BCG priming). After two vaccine boosts, animals were challenged via aerosolized Mtb (100–250 colony-forming units [CFUs]).

Figure 2.

Immunization with Nano-FP1 Equals or Enhances BCG-Derived Protection in Naive or Primed Animals, Respectively

(A–C) Protective efficacy of Nano-FP1 was measured in the low-dose aerosol Mtb challenge model. BCG priming (when done) was for 10 weeks, with all other experimental intervals 3 weeks apart. Three experiments in total were performed in London—2× BCG-primed background (A) and 1× unprimed (B)—and a further experiment on a BCG-primed background was performed in Stockholm (C). Immunization with BCG significantly reduced CFUs in lungs of challenged animals when compared with the PBS group in all experiments (A–C, p < 0.005). Immunization with Nano-FP1 afforded greater protection against Mtb H37Rv or Harlingen compared to immunization with BCG alone in BCG-primed (A and C, p < 0.01) or unprimed (B, p 0.04) animals. Each data point is representative of 1 animal. Lines represent mean ± SEM. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. i.n., intranasal; i.t., intratracheal.

Immunization with BCG alone led to a significantly reduced bacterial burden in the lungs in all experiments by an average of 0.7 log (p ≤ 0.005 for all experiments), compared with animals mock-immunized with PBS. BCG immunization also significantly reduced the spleen burden in 3/4 experiments by 1.2 log on average (p < 0.03 for all experiments). Strikingly, in all BCG-primed experiments, immunization with Nano-FP1 conferred significantly better protection than BCG alone (Figures 2A and 3C), reducing lung CFUs by a further 0.6 log on average, compared with BCG (p < 0.01 for all experiments). Moreover, protection in the lungs afforded by Nano-FP1 was significantly better than PBS on a BCG-naive background (Figure 2B, p = 0.04), giving comparable levels of protection as BCG. Importantly, we found that Nano-FP was also superior at preventing extra-pulmonary Mtb dissemination, as evidenced by significantly reduced Mtb CFUs in the spleens compared to BCG alone (p < 0.05). Therefore, we concluded that our vaccine could enhance protection by parenteral BCG but also offer similar levels of protection when administered in BCG-naive mice. Nano-FP1 efficacy was observed in two independent laboratories in two separate geographical locations (London and Stockholm).

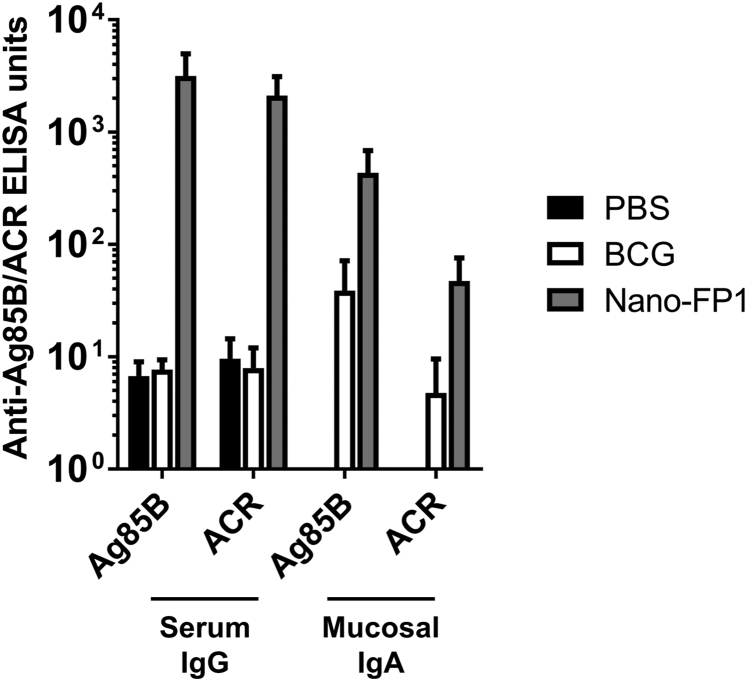

Figure 3.

Nano-FP1 Generates Antigen-Specific Antibody Responses in Blood and Mucus of Immunized Mice

ELISA of anti-Ag85B and -AcR IgG responses in sera or IgA in BAL of unimmunized animals or those immunized with BCG or Nano-FP1. Immunization with Nano-FP1 resulted in the production of high titers of fusion-protein antigen-specific IgG in the sera or of anti-Ag85B IgA in the lung mucosa. Negligible antibody responses were observed in naive mice or those immunized with BCG alone. Data represent means ± SEM of three animals per group and are representative of three separate experiments.

Nano-FP1 Induces Systemic and Mucosal Antibodies against Mtb Antigens

Given the ability of Nano-FP1 to enhance bacterial control, we hypothesized that the vaccine was broadly enhancing immunological function and first assessed whether humoral responses were being bolstered. An elegant study by Lu et al. has recently underscored the importance of antibody in controlling TB.19 Therefore, we measured antibody titers to the FP1 constituent antigens (Ag85B and Acr) in the blood and airway surface liquid of immunized animals as a measure of recognition of the Nano-FP1 vaccine by the immune system. Levels of specific immunoglobulin (Ig)G in the sera and IgA in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were assessed by ELISA and compared between the Nano-FP1, BCG, and PBS mock-immunized animal groups. Immunization with Nano-FP1 generated robust IgG and IgA responses to Ag85B in the sera and BAL (Figure 3), respectively, whereas ACR-specific responses were relatively lower, particularly in the BAL. The variable humoral responses indicate differential recognition of these FP1 component antigens but an overall boost to antigen-specific humoral immunity by Nano-FP1 when taken together. Interestingly, BCG alone induced minimal Ag85B/Acr-specific IgG or IgA responses.

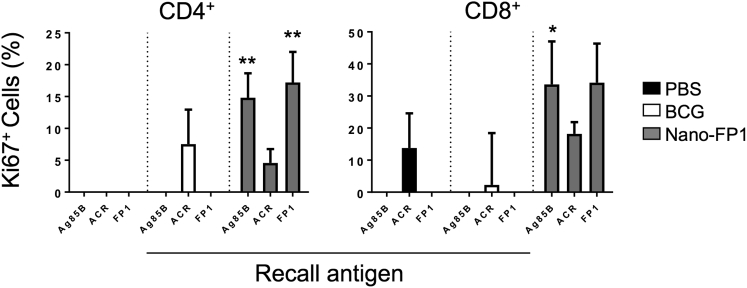

Enhanced Memory T Cell Proliferation Induced by Nano-FP1

Antibody class switching in naive B cells depends on T-dependent effector cytokines such as IFN-γ and interleukin (IL)-4. Since high IgG/IgA titers were observed after Nano-FP1 immunization, we speculated that there would be a co-occurring memory T cell response of similar magnitude. To measure memory T cell proliferation, splenocytes were pulsed with recall antigen, and the cell-cycle marker Ki67 was measured (Figure 4). As expected, no T cell proliferation was observed in the PBS control group upon exposure to recall antigen, with the exception of a small percentage of CD8+ T cells (∼7.5%) responding to Acr (possibly due to intrinsic immunomodulatory effects of Acr on APCs, as previously documented20). In the BCG vaccine group, there were modest responses to Acr in both the CD4 and CD8 compartments (<10% and <5% Ki67+, respectively) and no detectable responses to Ag85B, in keeping with studies showing that BCG induces sub-optimal antigen presentation in vivo.21 By contrast, large percentages of Ki67+ CD4+ (>15%) and Ki67+ CD8+ (>30%) T cells were detected in splenocytes from the Nano-FP1 vaccine group after stimulation with Ag85B or FP1, with values being markedly higher than those from BCG-vaccinated animals. Consistent with the levels of Acr-specific antibodies, there were muted but notable proliferative responses to Acr in the Nano-FP1 group. These data indicate that mucosal booster immunization with Nano-FP1 may lead to increased frequency of antigen-specific memory T cells compared to BCG alone.

Figure 4.

Splenocytes from Mice Immunized with Nano-FP1 Are Highly Proliferative

Spleens from immunized or control mice were stimulated with recall antigen for 6 days, and T cell proliferation was quantified by expression of Ki67, depending on expression of CD4 (left) or CD8 (right). Greater CD4 and CD8 T cell proliferation was observed in cells from the Nano-FP1 vaccine group in response to Ag85B of FP1 stimulation. Data represent mean ± SEM of pooled values from three animals and are representative of three separate experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Enhanced T Cell Cytokine Production by Nano-FP1

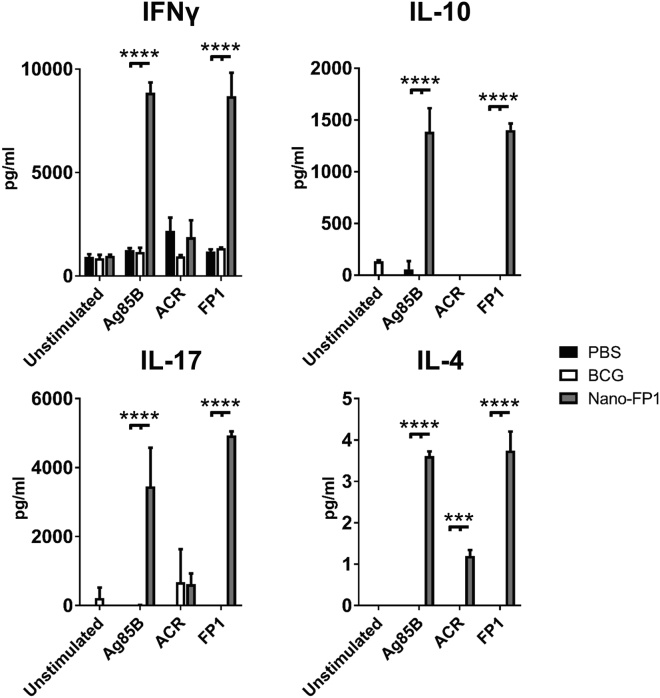

The enhanced T cell proliferative responses induced by Nano-FP1 led us to question what specific T cell phenotype was being induced by immunization. To address this, splenocytes from immunized animals were pulsed with recall antigens (Ag85B, Acr, or FP1), and levels of IFN-γ (Th1), IL-4 (Th2), IL-10 (Treg), and IL-17 (Th17) were quantified by multiplex flow cytometry. There were muted levels of all four cytokines in the BCG group in response to all recall antigens (Figure 5), which was consistent with the low levels of T cell proliferation previously detected. However, high levels of IFN-γ (>7,000 pg/mL), IL-10 (>2,000 pg/mL), and IL-17A (>3,000 pg/mL) were noted in the Nano-FP1 group in response to Ag85B and FP1, with Acr inducing more modest levels of these cytokines, although still more than BCG. These data suggested that Nano-FP1 was inducing a mixed Th1-Th17-Treg response in vivo. Both Th1 and Th17 cells have pivotal roles in protection against TB, and IL-10 is crucial for the survival of CD8+ memory T cells, suggesting a causal link between elevated IL-10 (Figure 5) and abundant CD8+ T cell proliferation in response to Ag85B.

Figure 5.

Splenocytes from Mice Immunized with Nano-FP1 Exhibit Strong Recall Cytokine Responses

Multiplex quantification of cytokine release by murine splenocytes in response to recall antigens. Splenocytes from animals immunized with Nano-FP1 showed strong cytokine responses after stimulation with Ag85B or FP1 but not Acr. Cytokine production in the PBS or BCG groups was low to minimal. Production in media alone was used as a negative control, and data represent cytokine production by splenocytes pooled from three animals per experimental group. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to test for statistical significance. ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

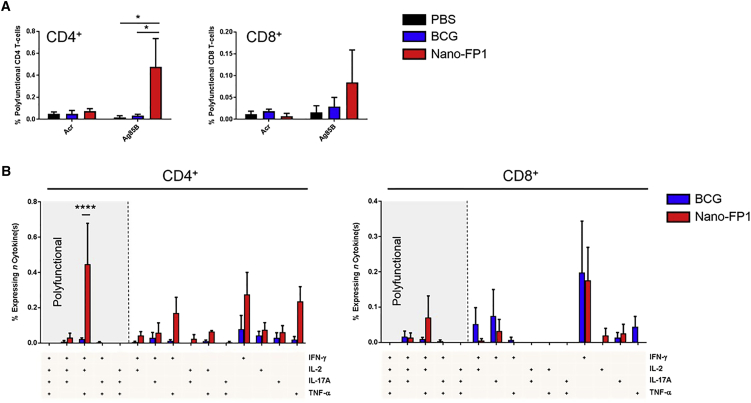

Nano-FP1 Boosts Ag85B-Specific CD4+ T Cell Polyfunctionality

Polyfunctional T cells are able to produce several effector cytokines concomitantly, and their presence during natural infection and immunization has been linked to protection against TB.22, 23 We hypothesized that Nano-FP1 was inducing a greater degree of T cell polyfunctionality that could potentiate control of Mtb compared with BCG alone. Splenocytes from immunized mice were, therefore, stimulated with the recall antigens Ag85B and Acr, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were interrogated for the presence of four effector cytokines: IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-17A, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). As can be seen in Figure 6A, mice immunized with Nano-FP1 had 0.47% polyfunctional (i.e., 3+ cytokine) CD4+ T cells in response to Ag85B, compared to only 0.03% in the BCG group (p < 0.05). In the CD8 compartment, there was a similar trend, with the Nano-FP1 group containing 0.08% polyfunctional T cells responsive to Ag85B, compared to only 0.03% in the BCG group. The responses to Acr, in line with previous observations, were more muted across all groups. Next, we probed specific Ag85B-dependent polyfunctionality in order to determine whether there were any distinct cytokine patterns between vaccine groups (Figure 6B). It was noted that Nano-FP1 strongly induced two subsets in CD4+ cells: IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+ (p < 0.05, Nano-FP1 versus BCG) and IFN-γ+TNF-α+, the former possibly representing actively proliferating (IL-2+) cells belonging to the latter subset. In CD8+ cells, there was a similar pattern; however, none of the groups reached statistical significance. Evidence suggests that IFN-γ+ IL-2+ TNF-α+ CD4+ T cells are a particularly protective subset in TB, exhibiting high proliferative capacity and resistance to exhaustion.24

Figure 6.

Nano-FP1 Induces High T Cell Polyfunctionality

Spleens from (n = 1–3) immunized or control mice were stimulated with recall antigen for 4 hr under Golgi blockade and then assessed for the production of four effector cytokines: IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-17A, and TNF-α. (A) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing 3 or more cytokines. (B) CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing specific combinations of cytokines in response to Ag85B re-stimulation. Data are derived from three independent experiments. Error bars depict means ± SEM. Significance was tested between groups by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test* p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001.

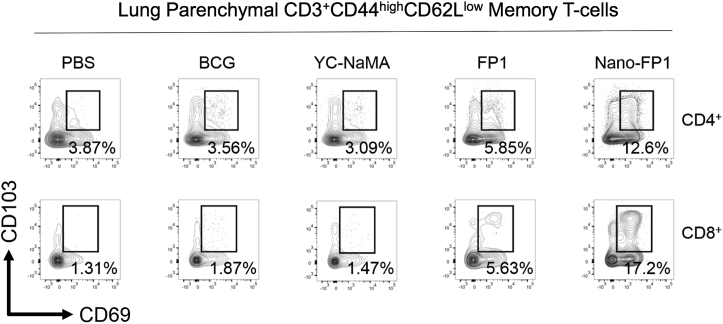

Pulmonary Seeding of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells after Nano-FP1 Immunization

Tissue-resident memory T cells (Trms) are lymphoid cells that do not circulate in the blood or lymphatic system. It has been reported that pulmonary Trms are efficiently induced by mucosal immunization with BCG or viral vectors expressing Mtb antigens and that these Trms offer rapid protection against Mtb infection.25, 26 Thus, we hypothesized that Nano-FP1, as a mucosal vaccine, was inducing this cell type. To test this, lungs from immunized mice were harvested and assessed for memory T cells (CD44highCD62Llow) expressing the Trm markers CD69 and CD103. To exclude for the possibility of these T cells being directed against the NP itself, YC-NaMA alone was also administered as a control. As shown in Figure 7, parenteral BCG alone was unable to induce an appreciable level of either CD4+ or CD8+ Trms, in line with other studies. Similarly, YC-NaMA had no effect on levels of CD69+CD103+ cells. FP1 alone was able to increase CD4+ Trms to 5.58% and CD8+ Trms to 5.63%, likely reflecting the high avidity of Ag85B for cognate T cell receptors (TCRs) even in the absence of adjuvant. Most strikingly, the complete Nano-FP1 vaccine was able to induce 12.6% CD4+ Trms and 17.2% CD8+ Trms. Although the TCR specificity of these cells remains to be elucidated, these are likely to be directed to FP1, given the fact that YC-NaMA is non-proteinaceous and lacks the intrinsic ability to induce Trms. Taken together, these data firmly suggest that Nano-FP1 can induce mucosal, tissue-resident memory T cells alongside lymphoid organ counterparts.

Figure 7.

Nano-FP1 Immunization Leads to Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in the Lungs

Lungs from immunized mice were perfused, and then memory T cells (CD44hiCD62Llo) were assessed for co-expression of CD69 and CD103 in tandem. Percentages of Trm are indicated in the relevant plots. Plots are representative and derived from n = 3 pooled mice per group.

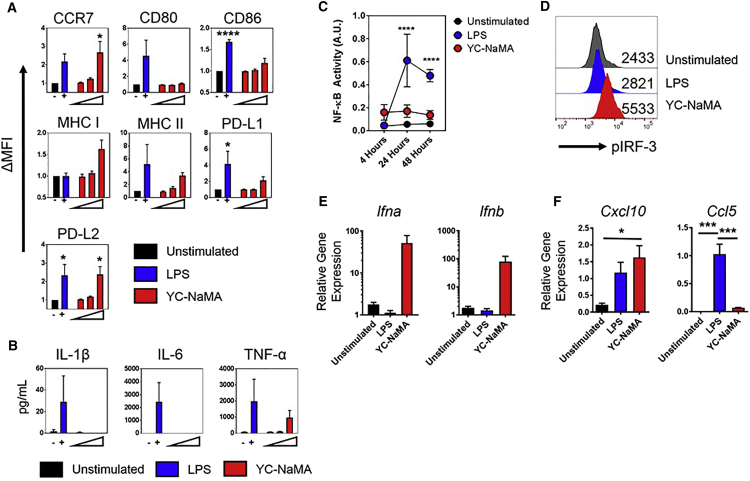

YC-NaMA NPs Activate APCs via IRF-3

The evidence thus far firmly established the ability of Nano-FP1 to enhance the bacterial control and immunogenicity afforded by the BCG vaccine, bolstering immunological parameters classically associated with protection against TB. However, despite the use of YC-NaMA in several experimental vaccines, its mode of action has hitherto remained unknown. Professional APCs such as macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and B cells are known to orchestrate the adaptive immune system, and we theorized that the NP component of Nano-FP could be acting as an adjuvant and inducing APC maturation, thus providing a mechanism for enhanced B and T cell immunogenicity and, ultimately, bacterial control. To test this, APCs were pulsed with YC-NaMA, and a comprehensive panel of activation markers was measured. We found that YC-NaMA was able to induce upregulation of numerous surface markers associated with APC activation (Figure 8A), including CCR7 (p < 0.05) and PD-L2 (p < 0.05). There was also a strong trend for upregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I, MHC class II, and modest upregulation of CD86 and PD-L1. Intriguingly, under the same conditions, YC-NaMA was unable to induce any detectable IL-1β or IL-6, with only weak TNF-α production, compared to the positive control lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

YC-NaMA Induces an IRF-3-Associated APC Activation Profile

Macrophages were assessed for various parameters of activation. (A) Macrophages were stimulated for 48 hr with 0.1, 1, or 10 μg/mL YC-NaMA or LPS and assessed for surface phenotype by flow cytometry. (B) Cytokine levels in the supernatants were determined by ELISA. (C) Macrophages expressing an alkaline phosphatase NF-κB reporter were pulsed with YC-NaMA (10 μg/mL) or LPS for indicated times and then assessed for reporter activity by reading optical density. (D) Phosflow detection of IRF-3 phosphorylation at 4 hr post-stimulation. (E) qRT-PCR of Ifna and Ifnb 24 hr post-stimulation, relative to housekeeping gene Actb. (F) qRT-PCR of Ccl5 and Cxcl10 at 24 hr post-stimulation, relative to housekeeping gene Actb.Data are derived from one (D), three (A–C), or four (E and F) independent experiments. Error bars depict means ± SEM. Significance was tested against the unstimulated control (A–C) or against other groups (F) by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (A, B, and F) or two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-test (C) *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001, ***p < 0.0001.

Since TLR-dependent inflammatory cytokine production is typically driven by MyD88-dependent NF-κB activation, whereas maturation markers are more dependent on TRIF-dependent IRF-3 activation causing an autocrine type I IFN loop,27, 28 we inferred that YC-NaMA was inducing an IRF-3-biased activation profile in APCs. Using a macrophage NF-κB reporter cell line, we found that, while LPS induced strong NF-κB-dependent gene transcription (p < 0.0001, 24 hr and 48 hr, LPS versus unstimulated cells), there was no significant induction of this pathway by YC-NaMA (Figure 8C), explaining the lack of inflammatory cytokines. However when IRF-3 was tested for activation by phosphorylation on serine 396, YC-NaMA strikingly induced almost double the level of phosphorylation observed in the positive control (LPS mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]: 2,821; YC-NaMA MFI: 5,533) (Figure 8D). Type I IFN production explicitly requires IRF-3/IRF-7 activation, and accordingly, we observed sustained and potent Ifna and Ifnb gene transcription (∼100-fold above Actb) due to YC-NaMA stimulation at 24 hr post-stimulation, at which point even LPS was not inducing either of these genes. To confirm our model of APC activation by YC-NaMA, we measured transcriptional levels of the chemokines RANTES (Ccl5) and IP-10 (Cxcl10) (Figure 8F). RANTES requires dual IRF-3/NF-κB cooperation within its promoter,29 whereas IP-10 is a classic interferon-stimulated gene induced by autocrine IFN-β.30 In accordance with our hypothesis, YC-NaMA induced significantly more IP-10 transcripts than unstimulated cells (p < 0.01) but diminished RANTES transcripts compared to LPS (p < 0.001). Collectively, these findings strongly support a novel mechanism of activity in which YC-NaMA is not immunologically inert but activates IRF-3 to drive maturation marker expression without the accompanying inflammation associated with NF-κB signaling, leading to enhanced cellular and humoral immunity.

Discussion

The use of BCG as a worldwide TB vaccine is unlikely to be discontinued. While it offers only limited protection against Mtb, it has the significant advantage of providing cross-protection against non-mycobacterial pathogens. BCG can enhance responses to pathogens such as C. albicans, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae via so-called “trained immunity” involving epigenetic priming of myeloid cells;31 accordingly, clinical trials have highlighted the role of BCG in lowering infant mortality independently of effects on TB.32 Given this situation, a novel TB vaccine would likely be used as a “booster” to pre-existing immunity offered by BCG.

In this study, we developed a novel fusion protein (FP1) and complexed this with YC-NaMA NPs: a cheap, abundant and safe source of NPs. The resultant vaccine, Nano-FP1, was tested in vivo via mucosal immunization and showed enhanced protection against the H37Rv and Harlingen Mtb strains in mice that were BCG primed. This increase in bacterial control was found in both the lungs and the spleen. Protection was associated with multi-system immunological activity. Remarkably, however, we also observed protection in BCG-naive mice. TB is the biggest killer of HIV-infected individuals globally, yet the use of BCG in this population or in otherwise immunocompromised individuals carries the risk of vaccine-induced disease; hence, there are safety concerns associated with this practice.33 Since Nano-FP1 is a subunit vaccine containing no live organisms, it has potential applications within this and other immunocompromised at-risk groups.

T cells are indispensable for protection against Mtb. Mice lacking CD4+ T cells succumb to Mtb-mediated lethality,34 and CD8+ T cells may provide a rapid response to pulmonary infection by directing cytotoxicity against infected macrophages.35 Our experiments showed that, in the Nano-FP1 booster group, exposure to recall antigen triggered a higher proliferative response (Ki67+) in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared to mice receiving BCG alone. This implies a higher number of central antigen-specific T cells in these animals or T cells with overall higher proliferative capacity. Since failure of the host to eradicate Mtb is linked with T cell exhaustion and terminal differentiation,36, 37 these data hold promise for Nano-FP1 as an effective vaccine.

Th1 and Th17 cells, in particular, have been implicated in protection against TB, and we observed elevated levels of both signature cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-17) in the spleens of Nano-FP1 immunized mice, compared to the levels seen with BCG immunization alone. Besides its conventional role in macrophage priming, IFN-γ can be advantageous during TB disease by acting in a regulatory role in antagonizing tissue-destructive neutrophils.38 Interestingly, we also noted elevated levels of IL-10, a cytokine classically associated with Treg and Tr1 subsets. While typically regarded as detrimental in TB, recent evidence from cellular analysis of granulomas in Mtb-infected cynomolgus macaques has shown that granulomas containing a mixture of both Th1/Th17 effector cells and IL-10+ regulatory T cells are strongly associated with sterilization,39 and Th1 cells that co-produce IL-10 are, in fact, more effective at licensing macrophages to kill intracellular pathogens.40 Levels of the cardinal Th2 cytokine, IL-4, were also elevated in recall groups; however, these levels are so negligible as to be physiologically irrelevant. By inducing cytokines associated with diverse helper T cell subsets, Nano-FP1 could be inducing a desirable and protective cellular profile while limiting collateral immune-mediated tissue destruction.

Alongside enhanced proliferative responses, we also found that mucosal delivery of Nano-FP1 led to the accumulation of lung parenchymal CD69+CD103+ memory T cells. Trm cells are an intriguing effect for any TB vaccine, since they offer the possibility of swift and specific control of Mtb before it can establish a microenvironment favorable to its own survival. The delay in T cell-mediated immunity during the early stages of infection has been described as a “bottleneck”41 in which T cells must egress from the lymph node to the lung tissue,42 and Trms are a potential solution to this problem. Investigating the TCR repertoire of Nano-FP1-induced Trms could further elucidate mechanisms of vaccine efficacy.

The role of T cell polyfunctionality in TB is controversial. While some studies have shown a role for these cells in protection, other studies have shown that T cells expressing multiple cytokines correlate with disease as opposed to protection. However, there is evidence that T cells expressing multiple cytokines are adequately primed, since detrimental conditions such as myeloid PD-L1 expression,43 inadequate antigen dose,44 and metabolic impairment45 can inhibit their generation. Therefore, in the context of vaccination at least, polyfunctional T cells are likely to be an indicator of optimal T cell priming. It has been suggested that the classical Th1 cytokines IFN-γ and TNF-α have distinct roles in the control of pulmonary Mtb and its extra-pulmonary dissemination, respectively.46 Since we observed enhanced levels of both cytokines co-expressed in polyfunctional CD4+ T cells (IFN-γ+IL-2+TNF-α+) in the Nano-FP1 group, this provides a possible explanation for enhanced protection in both lungs and spleen.

Nano-FP1 was able to enhance anti-Ag85B and anti-Acr IgG in the serum and IgA in the mucosa. The latter is indicative of engagement with the mucosal immune system and, therefore, confirms the success of our immunization route. Whether these humoral responses are protective or merely indicative of strong immune engagement remains unclear. Within a polyclonal antibody response, there is likely to be heterogeneity with regard to protective capability. Though considered an intracellular pathogen, Mtb can be found extracellularly during infection, thus raising the possibility of antibody involvement in immunity. Further work is necessary to elucidate the role of antibody—and, particularly, glycosylation of the Fc region—in protection against disease.

Interestingly, YC-NaMA was found to be a robust activator of the IRF-3-IFN signaling axis. The autocrine IFN loop in DCs has been noted to underpin the activity of chitosan as a particulate adjuvant.47 In this sense, the biological activity of YC-NaMA also strongly resembles that of the adjuvant MPLA. MPLA activates TLR-4 with a TRIF-IRF-3 bias,48 meaning that it can induce T cell responses without potentially pathological inflammation. MPLA required 3 decades of research and development to progress to use in humans,49 and we show here that similar effects can be achieved with a natural product from YC palm trees. We propose that the unconventional activation of APCs by YC-NaMA leads to vigorous T and B cell responses while maintaining the safety profile of the particle. In uncovering the biological activity of YC-NaMA, there is a case of “immunological irony,” in that Mtb exploits the IRF-3-IFN cascade to suppress cytokine production during natural infection.50 Here, we have used this as a tool to improve protection against the pathogen. Further work is needed to clarify the cellular targets of YC-NaMA NPs and investigate how its immunomodulatory functions can be modified to further enhance protection against TB.

The TB vaccine pipeline is relatively well stocked at the pre-clinical and early developmental stages but suffers from a high vaccine failure rate, leaving limited progression of vaccines to phase 3 clinical trials. Traditional vaccine approaches such as live attenuated or protein-adjuvant vaccines are still in development. However, recent years have seen a rise in the development of vaccines utilizing new technologies such as “improved BCG” vaccines, double-attenuated MTB vaccines, and virally vectored vaccine delivery platforms. The former two aim to target a “sweet spot” between immunogenicity and virulence. The feasibility of this approach is debatable and raises certain questions, particularly with regard to safety and preventing the return of virulence. These vaccines, unlike Nano-FP1, would not be safe to use in immunocompromised patients, nor would they be safe to use via the mucosal route, thus highlighting a benefit of our approach. Likewise, immunity generated by virally vectored vaccines can be often be inhibited by antiviral response. The pairing of the traditional (protein + adjuvant) with new technology (NPs) enabled us to design a vaccine that avoids the limitations found in some other approaches to TB vaccine development.

In summary, we show that Nano-FP1 is an effective mucosal TB vaccine that can induce a wide array of immunological benefits but also, most importantly, can offer improved protection against Mtb, when compared with the current vaccine BCG. The data herein illustrate the advantages of using a YC-NaMA-based nanoparticulate antigen delivery system and highlight the potential for repurposing these NPs toward other vaccines and therapeutics. Future work will involve exploiting the immunological mechanism(s) responsible for the activity of Nano-FP1 and optimizing the route of delivery to augment Nano-FP1 vaccine efficacy.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

All mice used in this study were used according to the UK national legislation (Animals in Scientific Procedures Act, 1986) and the Swedish Board of Agriculture and Swedish Animal Protection agency requirements - djurskyddslagen 1988:534; djurskyddsförordningen 1988:539; djurskyddsmyndigheten DFS 2004:4), as well as the local guidelines (St George’s University, London, UK; and Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden).

Vaccines

YC-NaMA NPs from Particle Sciences (Bethlehem, PA, USA) were supplied as a 10% w/v stock solution in water. FP1 was provided by Lionex (Braunschweig, Germany) and was composed of an N-terminal histidine tag, Acr (Rv2031c), Ag85B (Rv1886c), and the heparin-binding site of HBHA (Rv0475). FP1 was expressed in E. coli and purified via nickel ion chromatography. Purified FP1 was characterized by SDS-PAGE and probed for presence of constituent antigens using western blotting and anti-Ag85B/Acr antibody. Endotoxin content of purified FP1 was <7 IU/mg. Vaccines were formulated for 1 hr at room temperature prior to the addition of poly(I:C) (Sigma) immediately before immunization. Experimental animals received 10 μg FP1 in 0.1% w/v YC-NaMA and 20 μg poly(I:C) (Sigma) per immunization. Poly(I:C) was chosen as an adjuvant for its ability to stimulate Tc1 and Th1 responses.51

Bacteria

M. bovis BCG (strain Pasteur) and Mtb strains H37Rv and Harlingen were grown in 7H11 broth (Becton Dickinson) supplemented with OADC (Becton Dickinson) and enumerated on Mycobacteria Selectatab (Kirchner) selective 7H11 agar plates according to standard microbiological techniques. Animals were challenged via the aerosol route with ∼100 CFUs Mtb H37Rv per animal using a 3-jet Collison nebulizer (BGI) controlled by an AeroMP (Biaera Technologies), at St George’s, London, UK, or with ∼250 CFU using the In-Tox Products device (Small Animal Exposure System), at Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

NPs

YC-NaMA (Particle Sciences, USA) are lipidic NPs produced as previously described16 by emulsifying the wax of the YC palm with sodium myristate. Particle size and charge were determined using a NanoZS Zetasizer (Malvern, UK). A minimum of three readings were taken, and average NP size and zeta potential pre-, and post-protein adsorption were then calculated for quantification of protein adsorption. NPs and FP1 were incubated for 1 hr at room temperature, and the mixture was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min, after which free FP1 in supernatant was quantified by ELISA using a known concentration of FP1 as a standard.

Mice, Immunizations, and Sample Collection

Eight week-old C57BL/6J females were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Cambridge, UK). BCG-primed animals were immunized with 100 μL 2 × 105 CFU of BCG 10 weeks prior to vaccine boosting. For immunizations, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane followed by delivery of either 40 μL PBS or 40 μL Nano-FP1 vaccine via the intranasal or intratracheal routes. Animals received two vaccine boosts 3 weeks apart and were then challenged via the aerosol route with Mtb 3 weeks after the final boost. Three animals from each experimental group were culled immediately prior to challenge, and blood, spleens, and BAL were collected for immunogenicity testing. The remaining animals were sacrificed 3 weeks after challenge for organ CFU enumeration.

APC Activation

Macrophages (J774.1 cell line) were cultured in complete DMEM media (10% fetal calf serum [FCS], 10 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol—all from Sigma). For surface maturation, cells were stimulated for 48 hr with either lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 100 ng/mL, Sigma) or YC-NaMA (0.1, 1, or 10 μg/mL) and stained with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780 (eBioscience), and Fc receptors were blocked with TruStain fcX anti-mouse CD16/32 (BioLegend). Cells were then stained in flow cytometry buffer (PBS with 0.5% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide) with the following antibodies for 30 min at 4°C: CCR7-PerCP/Cy5.5, CD80-APC, CD86-PE/Cy7, H-2-FITC, I-A/I-E-Brilliant Violet 510, PD-L1-Brilliant Violet 421, and PD-L2-PE (all from BioLegend), followed by acquisition on a BD FACSCanto II and analysis on FlowJo v10 software. Compensation was performed by UltraComp Compensation Beads (eBioscience). Culture supernatants were tested for cytokines by ELISA in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Ready-Set-Go ELISA, eBioscience). Phosphorylation of IRF-3 was tested on cells fixed with 90% methanol, as previously described.52 For reporter assays, an NF-κB alkaline phosphatase reporter cell line (InvivoGen) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ELISAs

Serum IgG and mucosal IgA against Ag85B and Acr were measured by ELISA. Purified Ag85B and Acr from Lionex (Braunschweig, Germany) were used for ELISA plate coating (2 μg/mL). After blocking (PBS 1% BSA), mouse sera or lavage was diluted in PBS 1% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20, and added in 10-fold dilution series to a final dilution of 1:10,000 (sera) or 5-fold dilution series to 1:2,500 (BAL). Specific antibody was detected (1 hr at 37°C) with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG/A (Sigma) and OPD substrate (Sigma). Samples in triplicate were read at 482 nm on a plate reader (Tecan Infinite 200 Pro). Relative antibody titers were defined as the reciprocal of the dilution at the cutoff value, with cutoff values determined using the Frey method.53 Levels of FP1 were assessed as described earlier, where FP1 was used to coat plates (varying concentrations) and peroxidase-conjugated anti-His tag antibody (Sigma) was used to detect FP1 binding to the plate. The amount of FP1 present was calculated using a standard curve consisting of known concentrations of FP1.

T Cell Proliferation and Cytokines

Splenocytes were isolated from spleens homogenized by mechanical disruption through a 70-μm strainer (BD Biosciences). Erythrocytes were lysed by brief incubation with ACK Lysis Buffer (Invitrogen). Cells were seeded in technical duplicates in complete RPMI (10% FCS, 10 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol) at 1.5 × 106 cells per well and stimulated with 5 μg/mL recall antigen or 1 μg/mL α-CD3 antibody (BioLegend) for 6 days before supernatant recovery for cytokine quantification. For Ki67 staining, cells were stained with viability dye under Fc receptor blockade. Cells were stained with the following antibodies at optimized dilutions: CD4-PerCP/Cy5.5, CD8a-Brilliant Violet 510, and CD90.2-Brilliant Violet 421—all from BioLegend) for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized for 30 min at 4°C using the Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience), followed by intracellular staining (45 min, 4°C) using Ki67-APC (BioLegend). Cells were washed extensively and then acquired immediately on a BD FACSCanto II instrument. Compensation was done by using beads. Analysis was performed using FlowJo V10. Fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls were used to determine gating boundaries, and duplicate values were averaged within experiments, followed by background subtraction from an unstimulated control sample. Cells were gated by size (forward scatter [FSC]/side scatter [SSC]); singularity (area/width); viability (eFluor 780low); and CD90.2, CD4, CD8, and Ki67 expression. Levels of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-17 in culture supernatants were measured using the mouse LegendPlex kit (BioLegend), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were acquired on a BD FACSCalibur, and data were analyzed using the proprietary data analysis software (BioLegend).

T Cell Polyfunctionality

T cell polyfunctionality was assessed as previously reported,54 with minor modifications. Briefly, 1.5 × 106 splenocytes were seeded in complete RPMI in duplicate and stimulated with 5 μg/mL recall antigen in the presence of 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (Sigma). Some cells were additionally stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 100 ng/mL, Sigma) and ionomycin sulfate (20 μg/mL, Sigma). After 4 hr, cells were stained with viability dye under Fc receptor blockade as described earlier. Cells were fixed with BD Cytofix for 30 min at 4°C, followed by permeabilization in flow cytometry buffer containing 0.5% saponin (Sigma). Cells were incubated with an antibody cocktail (CD3-FITC, CD4-PerCP/Cy5.5, CD8α-Brilliant Violet 510, IFN-γ-Brilliant Violet 421, IL-2-PE, IL-17A-PE/Cy7, and TNF-α-APC—all from BioLegend) for 45 min at 4°C. Cells were extensively washed and then immediately acquired on a BD FACSCanto II. Compensation was performed as described earlier.

For analysis, FlowJo software v10 was used, and cells were gated by size (FSC/SSC), singularity (area/width), viability (eFluor 780low), and then T cell lineage (CD3+). Boolean gating was then used to determine individual cytokine combinations, using FMO and biological (PMA/ionomycin) staining controls to determine gating boundaries. Data were analyzed in Microsoft Excel by averaging technical duplicates, subtracting background cytokine production in unstimulated cells, and then applying a positivity threshold of 0.01%, as recommended by NIH guidelines.55 A gating strategy and representative data are shown in Figure S1.

RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

Macrophages (1 × 106 per condition) were stimulated for 24 hr and then lysed in RNeasy RLT lysis buffer (QIAGEN). mRNA was extracted by using the RNeasy Mini RNA Isolation Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA concentration was then measured by NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was synthesized using Superscript II (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and dNTPs (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. qPCR was performed using a SYBR Green (QIAGEN) ΔΔ-CT method56 relative to the housekeeping gene Actb. The following primers were used: Ifna (F): 5′-ATGGCTAGGCTCTGTGCTTTCCT-3′; Ifna (R): 5′-AGGGCTCTCCAGACTTCTGCTCTG-3′; Ifnb (F): 5′-ATGGTGGTCCGAGCAGAGAT-3′; Ifnb (R): 5′-CCACCACTCATTCTGAGGCA-3′; Ccl5 (F) 5′-AGATCTCTGCAGCTGCCCTCA-3′ (R) 5′-GGAGCACTTGCTGCTGGTGTAG-3′; Cxcl10 (F) 5′-GCCGTCATTTTCTGCCTCA-3′ (R) 5′-CGTCCTTGCGAGAGGGATC-3′; Actb (F): 5′- CCCTAAGGCCAACCGTGAAA-3′; Actb (R): 5′-GTCTCCGGAGTCCATCACAA-3′.

Lung T Cell Analysis

Lavaged lungs were perfused by extensively flushing the right cardiac ventricle with PBS. Excised tissue was then cut into ∼1-mm pieces, followed by incubation for 45 min in RPMI containing 1 mg/mL collagenase and 0.5 mg/mL DNase I (Roche). Cells were passed through a 40-μm strainer (BD Biosciences) and stained with viability dye under Fc receptor blockade, followed by staining with CD3-APC, CD4-PerCP/Cy5.5, CD8α-Brilliant Violet 510, CD44-FITC, CD62L-PE, CD69-PE/Cy7, and CD103-Brilliant Violet 421. Cells were gated as for proliferation, but also on the CD44highCD62Llow population.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests used are stated in the figure legends. GraphPad Prism 7 software was used for analysis of the results.

Author Contributions

P.H., A.C., and G.D. did all the pathogenic TB work and co-wrote the paper. S.H. did the in vitro immunogenicity of nanoparticles experiments. R.S., W.O., and M.S. designed, expressed, and provided the FP1 fusion protein. J.B. and M.R. performed the validation protection experiment at Karolinska Institute, Solna, Sweden. M.P. helped with data analysis. R.R. conceived the work and co-wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

W.O., R.S., and M.S. are employed by Lionex, GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Community H2020 (grant number 643558). We would like to acknowledge the provision of Yc-NaMA nanoparticles by Particle Sciences (Lubrizol) on a collaborative basis.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes one figure and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.016.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.World Health Organization. (2017). Global tuberculosis report 2017. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/.

- 2.World Health Organization. (2017). Global public goods for health - a reading companion. http://www.who.int/trade/distance_learning/gpgh/en/.

- 3.Migliori G.B., Pontali E., Sotgiu G., Centis R., D’Ambrosio L., Tiberi S., Tadolini M., Esposito S. Combined use of delamanid and bedaquiline to treat multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:E341. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson R., Diacon A.H., Everitt D., van Niekerk C., Donald P.R., Burger D.A., Schall R., Spigelman M., Conradie A., Eisenach K. Efficiency and safety of the combination of moxifloxacin, pretomanid (PA-824), and pyrazinamide during the first 8 weeks of antituberculosis treatment: a phase 2b, open-label, partly randomised trial in patients with drug-susceptible or drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Lancet. 2015;385:1738–1747. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray S., Mendel C., Spigelman M. TB Alliance regimen development for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016;20:38–41. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houben R.M.G.J., Menzies N.A., Sumner T., Huynh G.H., Arinaminpathy N., Goldhaber-Fiebert J.D., Lin H.H., Wu C.Y., Mandal S., Pandey S. Feasibility of achieving the 2025 WHO global tuberculosis targets in South Africa, China, and India: a combined analysis of 11 mathematical models. Lancet Glob. Health. 2016;4:e806–e815. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fine P.E.M. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet. 1995;346:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tameris M.D., Hatherill M., Landry B.S., Scriba T.J., Snowden M.A., Lockhart S., Shea J.E., McClain J.B., Hussey G.D., Hanekom W.A., MVA85A 020 Trial Study Team Safety and efficacy of MVA85A, a new tuberculosis vaccine, in infants previously vaccinated with BCG: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1021–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60177-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregory A.E., Titball R., Williamson D. Vaccine delivery using nanoparticles. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013;3:13. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harding C.V., Song R. Phagocytic processing of exogenous particulate antigens by macrophages for presentation by class I MHC molecules. J. Immunol. 1994;153:4925–4933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovacsovics-Bankowski M., Clark K., Benacerraf B., Rock K.L. Efficient major histocompatibility complex class I presentation of exogenous antigen upon phagocytosis by macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:4942–4946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.4942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffman S.L., Vekemans J., Richie T.L., Duffy P.E. The march toward malaria vaccines. Vaccine. 2015;33(Suppl 4):D13–D23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.07.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.European Medicines Agency (2015). First malaria vaccine receives positive scientific opinion from EMA. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2015/07/news_detail_002376.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1.

- 14.EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources Added to Food (ANS) Scientific opinion on the re-evaluation of carnauba wax (E 903) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2012;10:2880. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stylianou E., Diogo G.R., Pepponi I., van Dolleweerd C., Arias M.A., Locht C., Rider C.C., Sibley L., Cutting S.M., Loxley A. Mucosal delivery of antigen-coated nanoparticles to lungs confers protective immunity against tuberculosis infection in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014;44:440–449. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arias M.A., Loxley A., Eatmon C., Van Roey G., Fairhurst D., Mitchnick M., Dash P., Cole T., Wegmann F., Sattentau Q., Shattock R. Carnauba wax nanoparticles enhance strong systemic and mucosal cellular and humoral immune responses to HIV-gp140 antigen. Vaccine. 2011;29:1258–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lundqvist M., Stigler J., Elia G., Lynch I., Cedervall T., Dawson K.A. Nanoparticle size and surface properties determine the protein corona with possible implications for biological impacts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14265–14270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gessner A., Waicz R., Lieske A., Paulke B., Mäder K., Müller R.H. Nanoparticles with decreasing surface hydrophobicities: influence on plasma protein adsorption. Int. J. Pharm. 2000;196:245–249. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu L.L., Chung A.W., Rosebrock T.R., Ghebremichael M., Yu W.H., Grace P.S., Schoen M.K., Tafesse F., Martin C., Leung V. A functional role for antibodies in tuberculosis. Cell. 2016;167:433–443.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siddiqui K.F., Amir M., Gurram R.K., Khan N., Arora A., Rajagopal K., Agrewala J.N. Latency-associated protein Acr1 impairs dendritic cell maturation and functionality: a possible mechanism of immune evasion by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;209:1436–1445. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jagannath C., Lindsey D.R., Dhandayuthapani S., Xu Y., Hunter R.L., Jr., Eissa N.T. Autophagy enhances the efficacy of BCG vaccine by increasing peptide presentation in mouse dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2009;15:267–276. doi: 10.1038/nm.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Day C.L., Abrahams D.A., Lerumo L., Janse van Rensburg E., Stone L., O’rie T., Pienaar B., de Kock M., Kaplan G., Mahomed H. Functional capacity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cell responses in humans is associated with mycobacterial load. J. Immunol. 2011;187:2222–2232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seder R.A., Darrah P.A., Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection: implications for vaccine design. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:247–258. doi: 10.1038/nri2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woodworth J.S., Aagaard C.S., Hansen P.R., Cassidy J.P., Agger E.M., Andersen P. Protective CD4 T cells targeting cryptic epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resist infection-driven terminal differentiation. J. Immunol. 2014;192:3247–3258. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perdomo C., Zedler U., Kühl A.A., Lozza L., Saikali P., Sander L.E., Vogelzang A., Kaufmann S.H., Kupz A. Mucosal BCG vaccination induces protective lung-resident memory T cell populations against tuberculosis. MBio. 2016;7:e01686-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01686-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu Z., Wong K.W., Zhao H.M., Wen H.L., Ji P., Ma H., Wu K., Lu S.H., Li F., Li Z.M. Sendai virus mucosal vaccination establishes lung-resident memory CD8 T cell immunity and boosts BCG-primed protection against TB in mice. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1222–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen H., Tesar B.M., Walker W.E., Goldstein D.R. Dual signaling of MyD88 and TRIF is critical for maximal TLR4-induced dendritic cell maturation. J. Immunol. 2008;181:1849–1858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoebe K., Janssen E.M., Kim S.O., Alexopoulou L., Flavell R.A., Han J., Beutler B. Upregulation of costimulatory molecules induced by lipopolysaccharide and double-stranded RNA occurs by Trif-dependent and Trif-independent pathways. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:1223–1229. doi: 10.1038/ni1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Génin P., Algarté M., Roof P., Lin R., Hiscott J. Regulation of RANTES chemokine gene expression requires cooperativity between NF-kappa B and IFN-regulatory factor transcription factors. J. Immunol. 2000;164:5352–5361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holm C.K., Jensen S.B., Jakobsen M.R., Cheshenko N., Horan K.A., Moeller H.B., Gonzalez-Dosal R., Rasmussen S.B., Christensen M.H., Yarovinsky T.O. Virus-cell fusion as a trigger of innate immunity dependent on the adaptor STING. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:737–743. doi: 10.1038/ni.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinnijenhuis J., Quintin J., Preijers F., Joosten L.A., Ifrim D.C., Saeed S., Jacobs C., van Loenhout J., de Jong D., Stunnenberg H.G. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:17537–17542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins J.P., Soares-Weiser K., López-López J.A., Kakourou A., Chaplin K., Christensen H., Martin N.K., Sterne J.A., Reingold A.L. Association of BCG, DTP, and measles containing vaccines with childhood mortality: systematic review. BMJ. 2016;355:i5170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hesseling A.C., Schaaf H.S., Henekom W.A., Beyers N., Cotton M.F., Gie R.P., Marais B.J., van Helden P., Warren R.M. Danish bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine-induced disease in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;37:1226–1233. doi: 10.1086/378298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders B.M., Frank A.A., Orme I.M., Cooper A.M. CD4 is required for the development of a protective granulomatous response to pulmonary tuberculosis. Cell. Immunol. 2002;216:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00510-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lalvani A., Brookes R., Hambleton S., Britton W.J., Hill A.V.S., McMichael A.J. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiley W.W., Shafiani S., Wittmer S.T., Tucker-Heard G., Moon J.J., Jenkins M.K., Urdahl K.B., Winslow G.M., Woodland D.L. Distinct functions of antigen-specific CD4 T cells during murine Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19408–19413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006298107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jayaraman P., Jacques M.K., Zhu C., Steblenko K.M., Stowell B.L., Madi A., Anderson A.C., Kuchroo V.K., Behar S.M. TIM3 mediates T cell exhaustion during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005490. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nandi B., Behar S.M. Regulation of neutrophils by interferon-γ limits lung inflammation during tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:2251–2262. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gideon H.P., Phuah J., Myers A.J., Bryson B.D., Rodgers M.A., Coleman M.T., Maiello P., Rutledge T., Marino S., Fortune S.M. Variability in tuberculosis granuloma T cell responses exists, but a balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines is associated with sterilization. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004603. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jankovic D., Kullberg M.C., Feng C.G., Goldszmid R.S., Collazo C.M., Wilson M., Wynn T.A., Kamanaka M., Flavell R.A., Sher A. Conventional T-bet(+)Foxp3(-) Th1 cells are the major source of host-protective regulatory IL-10 during intracellular protozoan infection. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:273–283. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffiths K.L., Ahmed M., Das S., Gopal R., Horne W., Connell T.D., Moynihan K.D., Kolls J.K., Irvine D.J., Artyomov M.N. Targeting dendritic cells to accelerate T-cell activation overcomes a bottleneck in tuberculosis vaccine efficacy. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13894. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf A.J., Desvignes L., Linas B., Banaiee N., Tamura T., Takatsu K., Ernst J.D. Initiation of the adaptive immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis depends on antigen production in the local lymph node, not the lungs. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:105–115. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pen J.J., Keersmaecker B.D., Heirman C., Corthals J., Liechtenstein T., Escors D., Thielemans K., Breckpot K. Interference with PD-L1/PD-1 co-stimulation during antigen presentation enhances the multifunctionality of antigen-specific T cells. Gene Ther. 2014;21:262–271. doi: 10.1038/gt.2013.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiu Y.L., Shan L., Huang H., Haupt C., Bessell C., Canaday D.H., Zhang H., Ho Y.C., Powell J.D., Oelke M. Sprouty-2 regulates HIV-specific T cell polyfunctionality. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:198–208. doi: 10.1172/JCI70510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao E., Maj T., Kryczek I., Li W., Wu K., Zhao L., Wei S., Crespo J., Wan S., Vatan L. Cancer mediates effector T cell dysfunction by targeting microRNAs and EZH2 via glycolysis restriction. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:95–103. doi: 10.1038/ni.3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakai S., Kauffman K.D., Sallin M.A., Sharpe A.H., Young H.A., Ganusov V.V., Barber D.L. CD4 T cell-derived IFN-γ plays a minimal role in control of pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and must be actively repressed by PD-1 to prevent lethal disease. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005667. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carroll E.C., Jin L., Mori A., Muñoz-Wolf N., Oleszycka E., Moran H.B.T., Mansouri S., McEntee C.P., Lambe E., Agger E.M. The vaccine adjuvant chitosan promotes cellular immunity via DNA sensor cGAS-STING-dependent induction of type I interferons. Immunity. 2016;44:597–608. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mata-Haro V., Cekic C., Martin M., Chilton P.M., Casella C.R., Mitchell T.C. The vaccine adjuvant monophosphoryl lipid A as a TRIF-biased agonist of TLR4. Science. 2007;316:1628–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1138963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casella C.R., Mitchell T.C. Putting endotoxin to work for us: monophosphoryl lipid A as a safe and effective vaccine adjuvant. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:3231–3240. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8228-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Novikov A., Cardone M., Thompson R., Shenderov K., Kirschman K.D., Mayer-Barber K.D., Myers T.G., Rabin R.L., Trinchieri G., Sher A., Feng C.G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis triggers host type I IFN signaling to regulate IL-1β production in human macrophages. J. Immunol. 2011;187:2540–2547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Apostólico J.S., Lunardelli V.A., Yamamoto M.M., Souza H.F., Cunha-Neto E., Boscardin S.B., Rosa D.S. Dendritic cell targeting effectively boosts T cell responses elicited by an HIV multiepitope DNA vaccine. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:101. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bending D., Giannakopoulou E., Lom H., Wedderburn L.R. Synovial regulatory T cells occupy a discrete TCR niche in human arthritis and require local signals to stabilize FOXP3 protein expression. J. Immunol. 2015;195:5616–5624. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frey A., Di Canzio J., Zurakowski D. A statistically defined endpoint titer determination method for immunoassays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1998;221:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim M.Y., Van Dolleweerd C., Copland A., Paul M.J., Hofmann S., Webster G.R., Julik E., Ceballos-Olvera I., Reyes-Del Valle J., Yang M.S. Molecular engineering and plant expression of an immunoglobulin heavy chain scaffold for delivery of a dengue vaccine candidate. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017;15:1590–1601. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roederer M., Nozzi J.L., Nason M.C. SPICE: exploration and analysis of post-cytometric complex multivariate datasets. Cytometry A. 2011;79:167–174. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.21015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.