Abstract

The mitochondrial pro-apoptotic protein SMAC/Diablo participates in apoptosis by negatively regulating IAPs and activating caspases, thus encouraging apoptosis. Unexpectedly, we found that SMAC/Diablo is overexpressed in cancer. This paradox was addressed here by silencing SMAC/Diablo expression using specific siRNA (si-hSMAC). In cancer cell lines and subcutaneous lung cancer xenografts in mice, such silencing reduced cell and tumor growth. Immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy of the si-hSMAC-treated residual tumor demonstrated morphological changes, including cell differentiation and reorganization into glandular/alveoli-like structures and elimination of lamellar bodies, surfactant-producing organs. Next-generation sequencing of non-targeted or si-hSMAC-treated tumors revealed altered expression of genes associated with the cellular membrane and extracellular matrix, of genes found in the ER and Golgi lumen and in exosomal networks, of genes involved in lipid metabolism, and of lipid, metabolite, and ion transporters. SMAC/Diablo silencing decreased the levels of phospholipids, including phosphatidylcholine. These findings suggest that SMAC/Diablo possesses additional non-apoptotic functions related to regulating lipid synthesis essential for cancer growth and development and that this may explain SMAC/Diablo overexpression in cancer. The new lipid synthesis-related function of the pro-apoptotic protein SMAC/Diablo in cancer cells makes SMAC/Diablo a promising therapeutic target.

Keywords: apoptosis, cancer, mitochondria, SMAC/Diablo, phospholipid synthesis

Paradoxically, the mitochondrial pro-apoptotic protein SMAC/Diablo is overexpressed in several cancers. Silencing SMAC/Diablo expression in cancer cells and in mice lung cancer xenografts reduced cell and tumor growth and phospholipids levels. We demonstrate that SMAC/Diablo possesses a new lipid synthesis-related function essential for cancer growth, making SMAC/Diablo a promising therapeutic target.

Introduction

The canonical SMAC/Diablo (second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase/direct inhibitor of apoptosis-binding protein with low pI) isoform SMAC/Diablo-α is a pro-apoptotic mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) protein.1, 2 The N terminus of SMAC/Diablo serves as a mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS) and is cleaved to yield the mature 26 kDa protein.2 Following the induction of apoptosis, SMAC/Diablo is released into the cytosol,2, 3 where it interacts with members of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) family (cIAP1, cIAP2, and XIAP) to neutralize the inhibitory effects of IAPs on caspases and, thus, initiates apoptosis.4, 5 In interacting with IAPs, SMAC/Diablo acts as a homodimer, with contact being mediated via an N-terminal motif (Ala-Val-Pro-Ile).6 In addition, SMAC/Diablo was shown to be controlled by several other proteins, such as the Bcl-2 family of proteins,7 mitogen-activated protein kinase family members, such as Erk1/2,8 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase.9

Although there are a number of SMAC/Diablo variants generated by alternative splicing, SMAC/Diablo-α is the main IAP inhibitor.10 Another isoform, SMAC/Diablo-β, which lacks both the IAP-binding motif (IBM) and the MTS, can sensitize cells to apoptosis when overexpressed,11 suggesting that SMAC/Diablo may also serve functions that are IBM and mitochondria independent. Indeed, a cytosolic form, SMAC/Diablo-ε, which also lacks both IBM and MTS elements, is ubiquitously expressed in normal human tissues and cancer cell lines,12 is not involved in apoptosis and has been shown to be associated with tumorigenicity.13

Mice lacking SMAC/Diablo are viable, grow and mature normally, present embryonic fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and hepatocytes without any histological abnormalities, and exhibit wild-type responses to all types of apoptotic stimuli.14 As expected, overexpression of SMAC/Diablo was found to sensitize neoplastic cells to apoptotic death.15 SMAC/Diablo was found to be overexpressed in some cancers and downregulated in others. For instance, the expression levels of both SMAC/Diablo mRNA and protein were reduced in hepatocellular carcinoma cells, as compared to normal hepatic tissue,16 whereas higher levels were reported in cervical cancer,17 lung, ovarian, and prostate carcinomas, gastric carcinomas,18 renal cell carcinoma,19 and different types of sarcoma.20

The observation that SMAC/Diablo is overexpressed in cancer cells despite its role in promoting cell death suggests it might possess a new non-apoptotic function that has yet to be explored. This discrepancy is addressed here. We demonstrate that SMAC/Diablo possesses non-apoptotic functions associated with the regulation of phospholipid (PL) biosynthetic pathways essential for cancer development, such that silencing SMAC/Diablo expression reduced tumor size and altered the expression of many genes, while inducing differentiation of residual lung tumor cells to form alveoli-like structures and undergo microenvironment reorganization.

Results

Expression of SMAC/Diablo Protein in Tumors

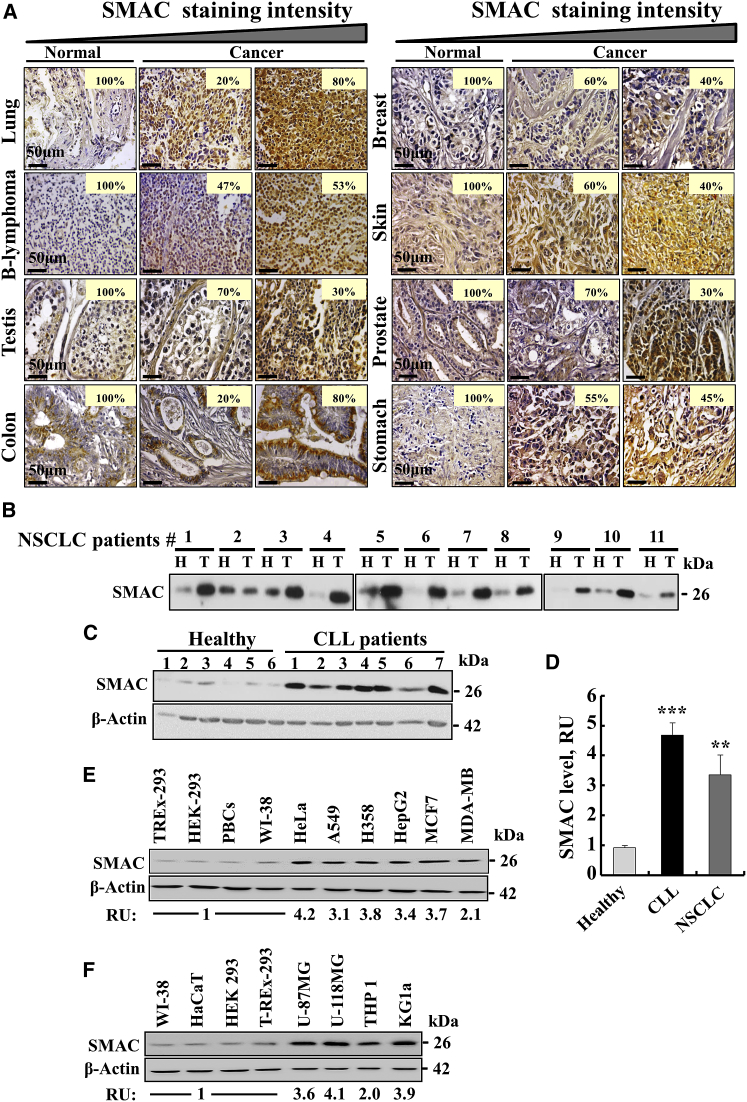

Expression levels of SMAC/Diablo in samples from 40 to 80 randomly selected normal controls or patients with different types of malignant cancer were assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) of tissue microarray slides using SMAC/Diablo-specific antibodies. Marked increases in SMAC/Diablo expression levels were observed in various cancers, including lung, B-lymphoma, testis, colon, stomach, breast, prostate, and skin (Figure 1A). No significant increases in SMAC/Diablo levels were observed in brain, ovary, uterine, bladder, cervix, uterus, esophagus, head and neck, intestinal mucous membrane, kidney, liver, or oral cavity cancer tissues (data not shown).

Figure 1.

SMAC/Diablo Is Overexpressed in Various Cell Lines and Types of Tumors

(A) Representative IHC staining of SMAC/Diablo in normal (n = 5) and cancerous (n = 20) tissue samples from tissue microarray slides (US Biomax) containing normal and cancer sections from lung, B-lymphoma, testes, colon, breast, skin, prostate, and stomach. Case % represents the percentages of patient samples that stained for SMAC/Diablo at the intensities presented in the scale at the top of the figure. (B) Representative immunoblot staining of tissue lysates of healthy (H) and tumor (T) tissues with anti-SMAC/Diablo antibodies, with each pair of samples (H, T) being derived from the same patient lung. (C) Representative immunoblots showing SMAC/Diablo expression in PBMCs derived from CLL patients or healthy donors. As a loading control, actin levels were probed using anti-β-actin antibodies. (D) Quantitative analysis of immunoblots of SMAC/Diablo expression levels in PBMCs from CLL patients, as compared to healthy donors (means ± SEM, n = 10) and in the NSCLC tumor, in comparison to healthy tissue from the same patient (means ± SEM, n = 11), presented as fold increase. (E and F) SMAC/Diablo expression levels in different cell lines, with the levels in the cancer cells being presented relative to those in the non-cancerous cells (bottom of the blot). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Levels of SMAC/Diablo expression were higher in samples of lung cancer (non-small-cell lung cancer [NSCLC]), relative to adjacent healthy tissue from the same lung (Figure 1B). Quantitative analysis showed 3.5-fold higher levels of SMAC/Diablo expression in NSCLC patient samples, relative to corresponding healthy tissue (Figure 1D). Immunoblotting analysis showed an approximately 5-fold increase in the expression of SMAC/Diablo in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients, as compared to PBMCs from healthy donors (Figures 1C and 1D).

Expression levels of SMAC/Diablo in cancerous cell lines, including HeLa, A549, H358, HepG2, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, U-87MG, U-118MG, THP1, and KG-la cells, were about 2- to 4-fold higher than in the non-cancerous TREx-293, HEK293, HaCaT, and WI-38 cell lines, as well as in primary mouse brain cells (PBCs) (Figures 1E and 1F).

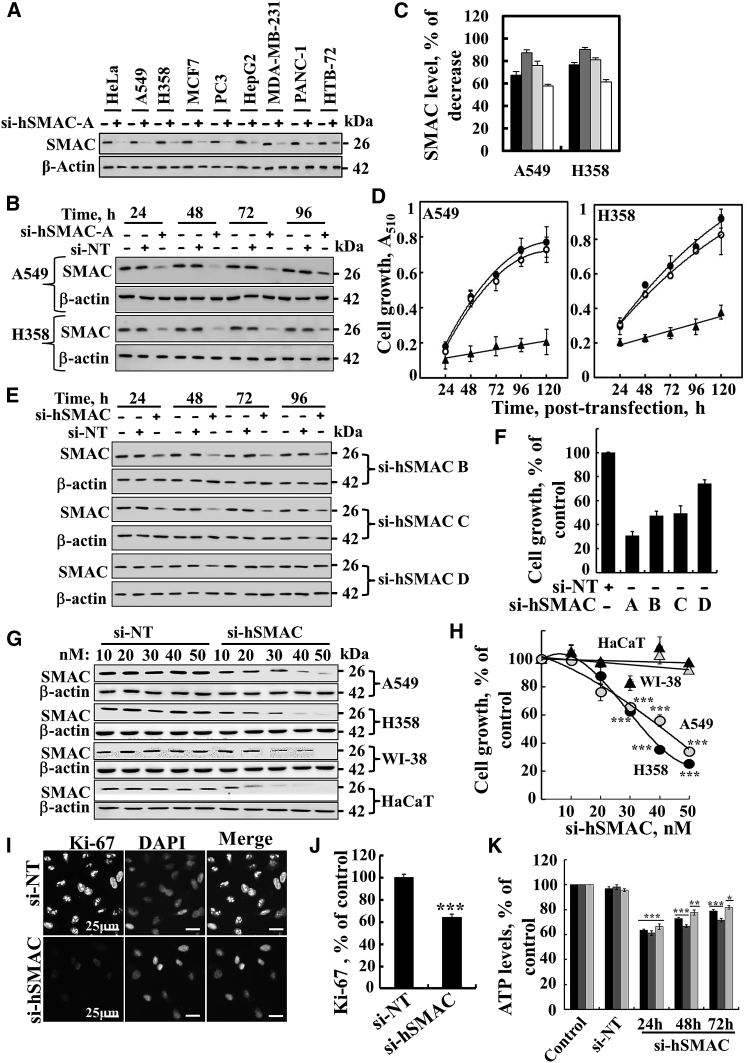

SMAC/Diablo Silencing Inhibits Cell Growth

To explore possible functions for SMAC/Diablo in cancer, its expression in a number of human-derived cancer cell lines of various origins (i.e., HeLa, A549, H358, MCF-7, PC3, HepG2, MDA-MB-231, PANC-1, and HTB-72 cells) was silenced using siRNA specific to human SMAC/Diablo (si-hSMAC-A). SMAC/Diablo expression levels were markedly decreased (80%–90%) in all tested cell lines (Figures 2A and S1A), with a maximum of 90% decrease seen after 48 hr. Ninety-six hours post-transfection this level dropped to 65% (Figures 2B, 2C, S1B, and S1C).

Figure 2.

Silencing with si-hSMAC-A Inhibits Cell Growth

(A) The indicated cancer cell lines were transfected with si-hSMAC-A (50 nM), and 48 hr post-transfection, levels of SMAC/Diablo in the cells were evaluated by immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) A549 and H358 cells were transfected with si-NT or si-hSMAC-A, and at the indicated time, cells were harvested and analyzed for SMAC/Diablo levels by immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. In (C), quantitative analysis of the immunoblot was carried out (presented as % of decreased expression) for all cell lines at 24 (black bar), 48 (light gray bar), 72 (dark gray bar), and 96 hr (white bar) post-transfection (means ± SEM, n = 3). (D) A549 and H358 cells were untreated (filled circle) or transfected with si-NT (open circle) or si-hSMAC-A (50 nM) (filled triangle), and cell growth was assayed at the indicated times using the SRB method (means ± SEM, n = 3). (E) A549 cells were transfected with si-NT or si-hSMAC B, C, or D (50 nM), and at the indicated times, cells were harvested and analyzed for SMAC/Diablo levels by immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. (F) Bar graph represents inhibition of growth of A549 cells treated with si-NT or si-hSMAC B, C, or D (50 nM) (means ± SEM, n = 3). (G and H) The A549, H358, HaCaT, and WI-38 cell lines were transfected with the indicated concentrations (10–50 nM) of si-NT or si-hSMAC-A. After 48 hr, SMAC/Diablo levels in the cells were analyzed by immunoblotting (G), and cell growth was assayed (H) (means ± SEM, n = 3). (I) si-NT- or si-hSMAC-A (50 nM)-treated A549 cells were analyzed for Ki-67 expression using specific antibodies, while nuclei were stained with DAPI. (J) Quantitative analysis of Ki-67-positive cells (means ± SEM, n = 3). (K) Quantitative analysis of Ki-67 staining intensity performed using ImageJ software (means ± SEM, n = 3). ***p < 0.001.

The effect of SMAC/Diablo silencing on cell growth was examined using the sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay. In the three cell lines tested (HeLa, A549, and H358), a 70%–80% decrease in cell proliferation was observed 120 hr post-transfection with si-hSMAC-A, the most active siRNA, whereas control cells transfected with non-targeting siRNA (si-NT) showed no significant effect on cell growth (Figures 2D and S1D).

Three other siRNAs designed to target hSMAC (B to D) were also found to inhibit SMAC/Diablo expression and cell growth to various degrees (Figures 2E and 2F). In immortalized non-cancerous cell lines, including WI38 and HaCat cells, si-hSMAC-A decreased SMAC/Diablo expression (Figure 2G), yet did not affect cell growth (Figure 2H). Lung cancer cells treated with si-hSMAC-A showed a decrease (35%) in the number of cells expressing cell proliferation factor Ki-67 (Figures 2I and 2J; Table S1). Analysis of Ki-67 staining intensity (Figure 2K) indicated a decrease of about 85% in intensity. As Ki-67 levels are increased with cell cycle progression, this decrease in expression suggests that cells treated with si-hSMAC-A do not advance in the cell cycle. Cell cycle analysis revealed an about 3-fold increase in the number of cells in S-phase in si-hSMAC-treated A549 cells relative to si-NT-treated cells (Figure S1H; Table S1), suggesting that SMAC/Diablo-depleted cells have decreased capacity to proceed in S phase. Consequently, BrdU incorporation was reduced by 35% (Figure S1I; Table S1). A positive linear correlation between the BrdU incorporation rate and the fraction of cells in S phase has been reported, with S phase arrest resulting in decreased BrdU incorporation.21

Silencing SMAC/Diablo in HeLa, A549, and H358 cells reduced cellular ATP levels by 20%–35% (Figure S1J), which may partially contribute to the inhibition of the cell growth seen. In contrast, SMAC/Diablo silencing had no effect on the overall production of reactive oxidative species (ROS), either in cells, as analyzed by 2', 7'-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence, or in mitochondria, as measured by MitoSOX Red, a mitochondrial superoxide indicator (Figure S2).

There was no significant cell death (5%–10%) of HeLa, A549, or H358 cells silenced for SMAC/Diablo expression (Figures S3A–S3C), suggesting that the decrease in cell growth was due to inhibition of cell proliferation rather than enhanced cell death. As expected, cell death was induced by selenite. Moreover, apoptosis was induced by overexpressing SMAC/Diablo or SMAC/Diablo-GFP in HeLa, A549, and H358 cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, again as expected (Figures S3D–S3F).

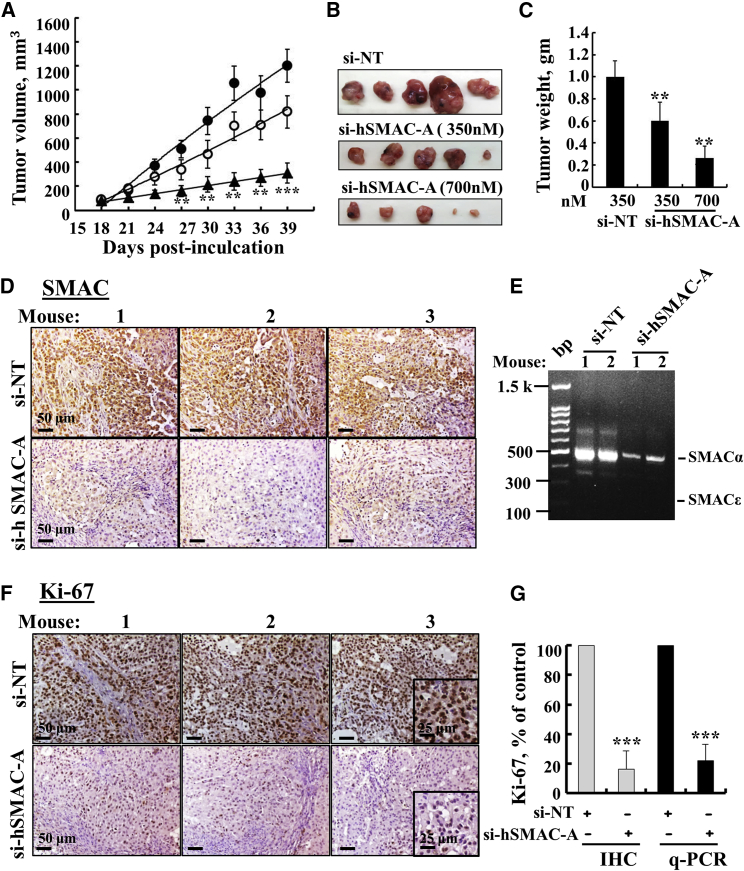

Silencing SMAC/Diablo Expression Inhibits Tumor Growth in Mice

The effect of si-hSMAC-A was tested on a subcutaneous (s.c.) tumor xenograft of A549 cells established in nude mice (Figure 3). Following tumor formation (75–90 mm3), the mice were divided into three matched groups and injected every 3 days with either si-NT (group 1) or si-hSMAC-A at 350 nM (group 2) or 700 nM (group 3). Tumor growth was followed for 39 days (Figure 3A). si-NT-treated tumor (TT) volume increased 13-fold, whereas 700 nM si-hSMAC-A treatment reduced growth markedly (Figure 3A). Comparing tumor sizes at the end-point revealed decreases of 35% and 85% in the volume of tumors treated with si-hSMAC-A at the 350 nM and 700 nM levels, respectively.

Figure 3.

si-hSMAC Inhibits Tumor Growth of Lung Cancer Xenografts

(A) A549 cells were inoculated into nude mice (3 × 106 cells/mouse). Tumor volumes were monitored, and on day 18, mice with similar average volumes (75–90 mm3) were divided into three groups (means ± SEM, n = 5). Xenografts were injected with si-NT (filled circle; 350 nM) or si-hSMAC-A (350 nM [open circle] or 700 nM [filled triangle]). The sizes of the xenografts were measured, and average tumor volumes were calculated and are presented as means ± SEM, **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001. Representative photographs (B) and weights (C) of dissected tumors from mouse A549 cell xenografts after treatment with si-NT or si-hSMAC-A (means ± SEM, n = 5). (D) Representative sections from si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with anti-SMAC/Diablo antibodies. (E) Expression of α- and ε-SMAC/Diablo isoforms in RNA isolated from si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs was determined using qPCR and specific primers. (F) Representative sections from si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with anti-Ki-67 antibodies. (G) Quantitative analysis of Ki-67-positive cells in IHC (gray bars) and mRNA (black bars) levels in si-NT-and si-hSMAC-A-TTs (means ± SEM, n = 3). ***p ≤ 0.001.

All mice were sacrificed 39 days post-cell-inoculation, and the tumors were excised (Figure 3B) and weighed (Figure 3C). This revealed 40% and 75% decreases in tumor weight for 350 and 700 nM si-hSMAC-A-TTs, respectively, values similar to the calculated tumor volumes (Figure 3A). Half of each tumor was excised and fixed, and paraffin sections were analyzed by IHC. si-NT-TTs were strongly immunostained with anti-SMAC/Diablo antibodies. As expected, SMAC/Diablo staining was very weak in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure 3D). Similar results were obtained using qPCR (Figure S5B). No expression of the alternative splice variant SMAC/Diablo-ε was found in the A549-derived tumors (Figure 3E), although this isoform was previously detected in healthy human tissues and in several cancer cell lines.12

The expression levels of the cell proliferation factor Ki-67, as analyzed by IHC staining or qPCR, were markedly decreased (∼80%) in the si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figures 3F and 3G; Table S1). Similar results were also obtained with breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure S4).

Silencing of SMAC/Diablo Alters the Expression of Apoptosis-Associated Proteins

TUNEL staining revealed a lack of apoptosis in either si-NT-TTs or si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure S5). As SMAC/Diablo released from mitochondria during apoptosis binds to and counters the activities of IAPs, leading to the release of bound caspases,1 we analyzed the expression levels of XIAP1, cIAP1, and cIAP2 genes, as well as levels of pro-apoptotic proteins, such as caspases 3, 8, and 9, Cyto c, and AIF. The expression levels of these genes were noticeably decreased, as revealed by qPCR (Figures S5B and S5C) and IHC (for XIAP; Figure S5D).

As found with cell culture, immunoblotting (Figures S6A and S6B), and qPCR (Figure S6C) of HeLa, A549, and H358 cells treated with si-hSMAC-A revealed decreases in the levels of expression not only of SMAC/Diablo but also of its binding protein, XIAP. SMAC/Diablo silencing also affected expression levels of apoptosis-related proteins, including caspases 3, 8, and 9, albeit in a transient manner, with increased expression being seen, followed by a decrease 96 hr post-transfection.

These results thus suggest cross-talk between the levels of expression of SMAC/Diablo and those of a variety of apoptosis-related proteins.

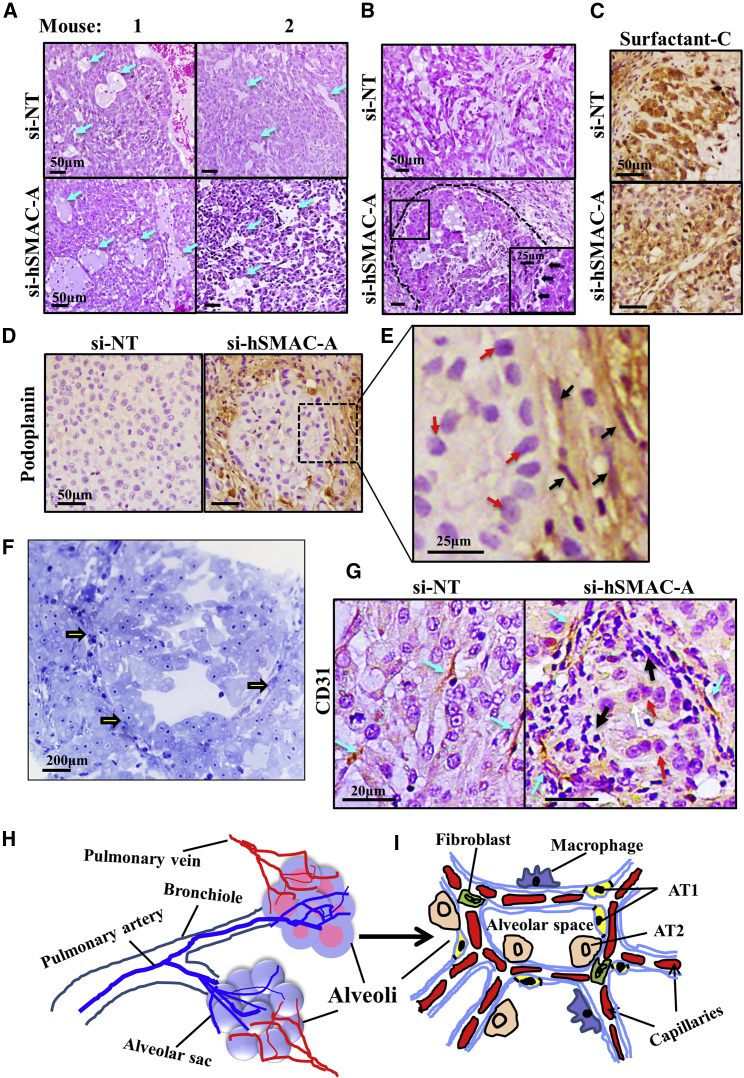

Silencing SMAC/Diablo Expression Alters Residual Tumor Morphology

H&E staining of sections from si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs demonstrated a mostly similar morphology of lung cancer tissue, including cyst-like structures (Figure 4A). However, further morphological analysis revealed that in si-hSMAC-A-TTs, the cells were organized in glandular alveolar-like clusters, surrounded by a chain of cells (Figure 4B, inset) that were not seen in si-NT-TTs (Figure 4B). These features can be interpreted as indicative of the A549 cells having undergone a differentiation process.

Figure 4.

Morphological Changes Induced in Tumors Treated with si-hSMAC

(A) Representative sections from si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with H&E. (B) Enlarged images of representative sections from si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with H&E, showing glandular-like clusters surrounded by a chain of cells (black arrows) in si-hSMAC-A-TTs. (C–E) Sections from si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with anti-prosurfactant C (C) or anti-podoplanin antibodies (D). (E) Enlarged image of representative section from si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with anti-podoplanin antibodies showing cells with elongated nuclei, AT1-like cells (black arrows), and non-stained cells, with AT2-like cells presenting big circular nuclei (red arrows). (F) Photomicrograph of si-hSMAC-A-treated tumor stained with toluidine blue. Arrows indicate glandular-like clusters surrounded by a chain of cells. (G) Representative sections from si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with anti-CD31 antibodies. Blue arrows indicate alveolar-like capillaries. Black and red arrows indicate AT1-like and AT2-like cells, respectively. (H and I) A schematic presentation of a cross-section through alveoli, with major cell types indicated.

In lung, pulmonary alveolar type I (AT1) cells are long and thin flattened squamous cells that account for ∼95% of the alveolar surface and lie adjacent to capillary endothelial cells to form the pulmonary gas exchange region. Alveolar epithelial type II (AT2) cuboidal surfactant-producing cells cover the remaining 5% of the alveolar surface.22, 23 AT2 cells can trans-differentiate into AT1 cells so as to repair damage24 and maintain normal lung architecture.25, 26, 27 To investigate this ability, we analyzed the expression of the pulmonary-associated surfactant protein C (SP-C) (Figure 4C), a component of the surface-active lipoprotein complex that is required for the proper biophysical functioning of the lung and is expressed in AT2 cells24, 25, 26 in A549 cells, considered AT2-type cells.28 No significant differences in the staining of SP-C in si-NT-TTs and si-SMAC-A-TTs were found (Figure 4C).

The expression of the AT1 cell marker podoplanin (also known as T1α or PDPN), a membranal mucin-type sialoglycoprotein,24 was also assessed. Podoplanin staining was only observed in si-hSMAC-A-TTs, with stained cells surrounding an area of cells resembling AT2 cells (Figures 4D and 4E). The podoplanin-stained cells included cells with an elongated nucleus (Figure 4E), which may represent AT1 cells. This was also shown in si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with toluidine blue, showing glandular-like clusters surrounded by a chain of cells (Figure 4F). This is in agreement with the suggestion that cells in the residual tumor had undergone differentiation into AT1-like cells. Further structural analysis revealed that the cells that had created a chain around the glandular-like structures were positively stained for the endothelial cell marker CD31 (Figures 4G and S7A–S7C) and were organized in a manner resembling lung alveoli. In contrast, in si-NT-TTs, the CD31-positive cells were flattened and randomly dispersed over the entire area of the tumor tissue (Figures 4G and S7A).

The results of the histological analysis could reflect a scenario whereby si-NT-TT CD31-positive cells are involved in the process of tumor angiogenesis, while in si-hSMAC-TTs, the cellular organization more closely resembles the normal physiological alveolar endothelial arrangement designed for O2 exchange. A schematic presentation of a cross-section through alveoli is offered for comparison with the glandular-like structures observed in the si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figures 4H and 4I).

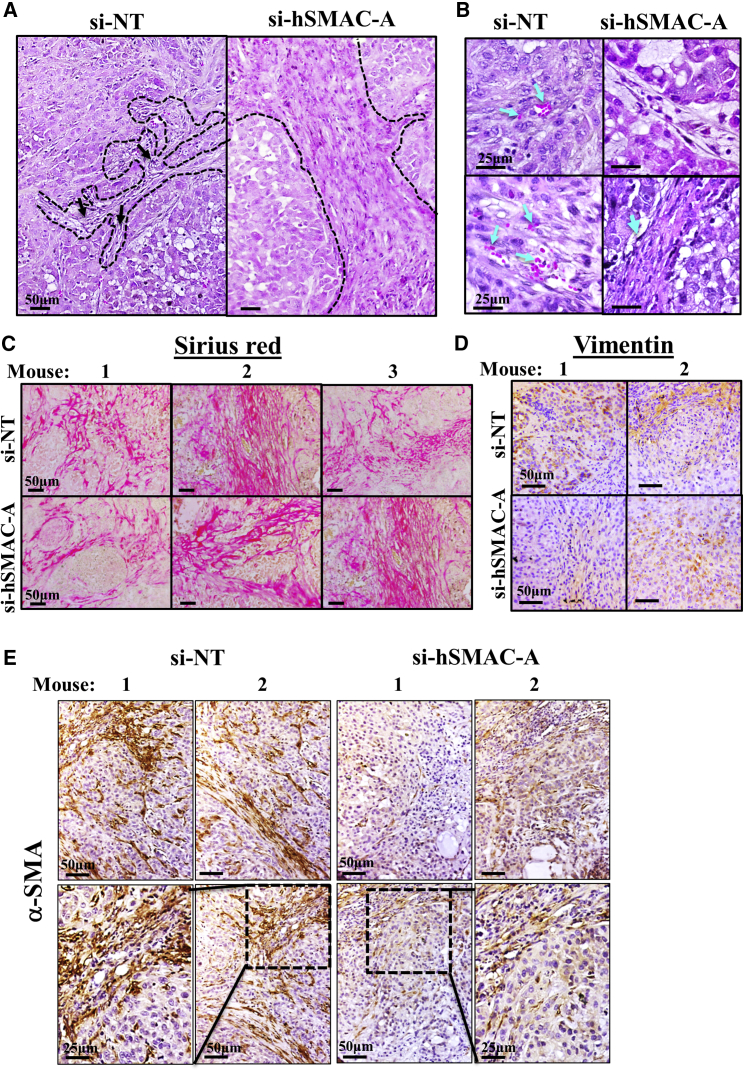

Further support for this view comes from analysis of the formation of stroma in H&E-stained si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure 5). While the stromal structures in si-NT-TTs were thin, appeared fragile-like, and were dispersed throughout the tissue, in si-hSMAC-A-TTs, massive fibrotic structures resembling scar tissue could be seen (Figure 5A). In addition, the stromal structures in si-NT-TTs were enriched with vascular formations associated with angiogenesis that were barely noticeable in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Staining of Stromal Markers in si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs

Representative sections from si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with H&E showing stromal structures (A) and vascular formation with red blood cells (blue arrows) in si-NT-TTs but not si-hSMAC-TTs (B). Representative sections from si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs stained with Sirius red (C), vimentin (D), and anti-α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) antibodies (E).

Sirius red and vimentin staining of collagen and intermediate filaments, respectively, is associated with tumor-stromal activity.29 The similar staining with Sirius red and vimentin in si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figures 5C and 5D) is indicative of no significant differences in mesenchymal cell presence and collagen production in the si-NT- and si-SMAC-A-TTs. In contrast, staining for α-SMA, a myofibroblast and cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) marker, was observed mainly in si-NT-TTs and was significantly reduced in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure 5E), suggesting reduced myofibroblast infiltration and/or CAFs. These results demonstrate distinctions in mesenchymal cell activity associated with tumorigenicity and scar stromal formation (associated with normal wound healing) between si-NT- and si-hSMAC-TTs.

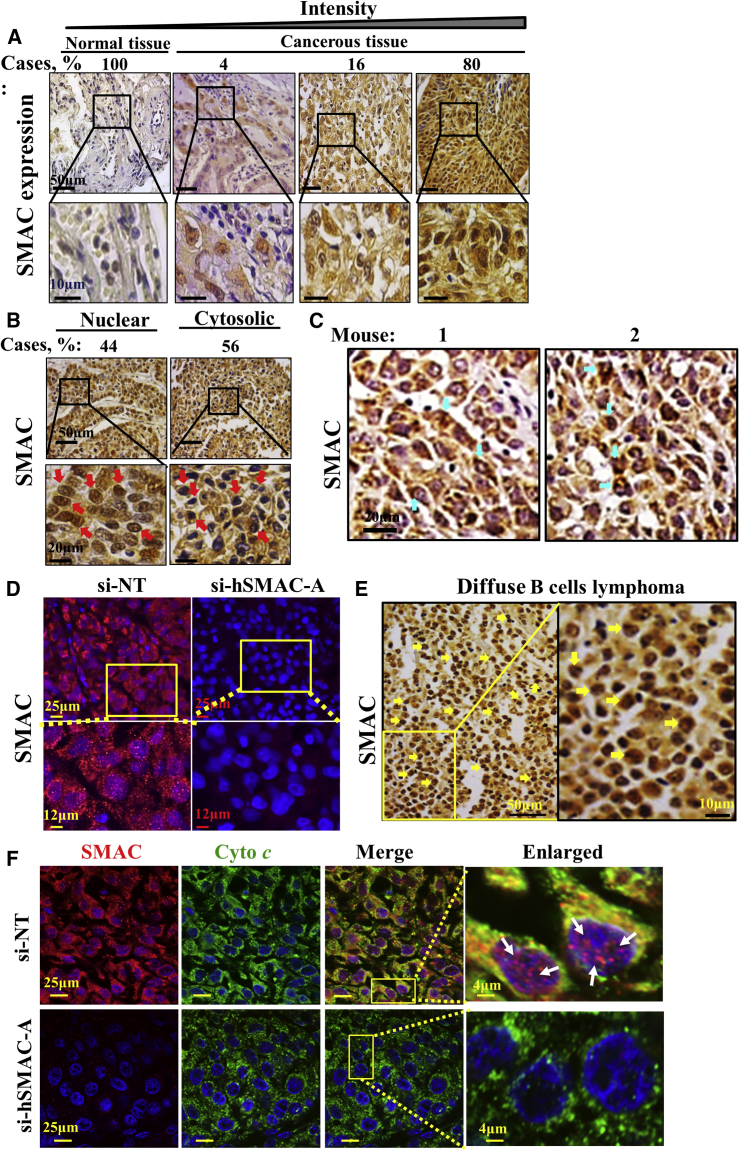

Overexpressed SMAC/Diablo Is Found in the Nucleus and Cytosol

Interestingly, we noted that although SMAC/Diablo is known as a mitochondrial protein, high levels were also detected in the nucleus and cytosol of NSCLC tissue microarray samples (Figure 6A). IHC analysis revealed that SMAC/Diablo was found in the nucleus in ∼50% of the samples (Figure 6B). Nuclear localization of SMAC/Diablo was also detected in si-NT-TTs by IHC (Figure 6C) and immunofluorescent staining (Figure 6D). However, analysis of various types of cancer (Figure 1) detected nuclear localization of SMAC/Diablo, in addition to NSCLC, only in diffuse B-lymphoma (Figure 6E). Cytosol-localized SMAC/Diablo was also found in NSCLC tumors overexpressing SMAC/Diablo (Figures S7D and S7E).

Figure 6.

Nuclear and Mitochondrial Localization of SMAC/Diablo

(A) IHC staining of SMAC/Diablo expression in normal and cancerous lung tissues from tissue microarray slides (US Biomax). The percentage indicates the proportion of samples (n = 70) stained with the indicated intensity. (B) Representative IHC images showing nuclear localization of SMAC/Diablo in lung cancer tissue. (C) Representative sections from si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs derived from A549 cells stained with anti-SMAC/Diablo antibodies. Blue arrows point to positive immunostaining of the SMAC/Diablo in nuclei. (D) Immunofluorescent SMAC/Diablo and DAPI staining of representative sections from si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs. (E) Representative IHC staining of B-lymphoma from tissue microarray slides stained with anti-SMAC/Diablo antibodies. Yellow arrows point to positive immunostaining of the protein in nuclei. (F) Representative immunofluorescence staining of sections from si-NT-TTs and si-hSMAC-A-TTs showing co-localization of SMAC/Diablo (red) and cytochrome c (green) in the mitochondria and of SMAC/Diablo, with DAPI (blue) staining of nuclei. White arrows in the enlarged image point to SMAC in the nucleus.

The subcellular localization of SMAC/Diablo in si-NT-TTs was further analyzed by immunofluorescent staining using anti-Cyto c antibodies as mitochondria markers and confocal microscopy (Figure 6F). The results show high co-localized staining of SMAC/Diablo and Cyto c in si-NT-TTs, as reflected in the merged images. Here too, SMAC/Diablo was found in the nucleus. As expected, no SMAC/Diablo was detected in si-hSMAC-A-TTs.

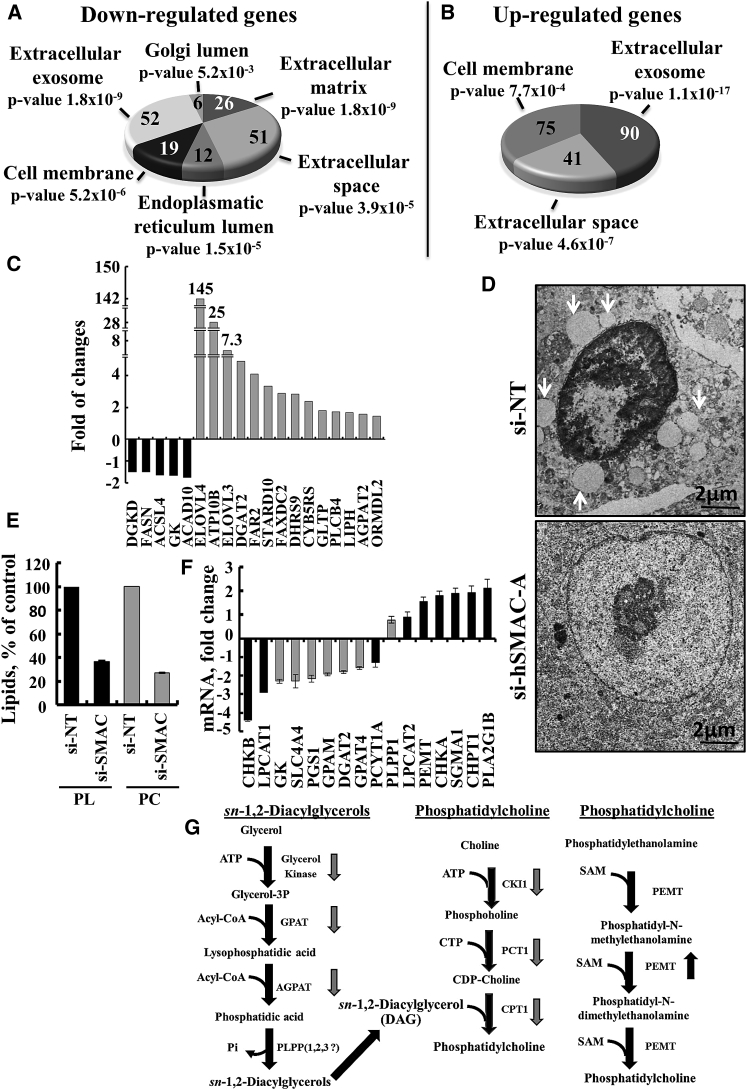

NGS and Functional Analysis of si-NT- and si-hSMAC-TTs

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was used to investigate changes in patterns of gene expression in si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure 7; Tables S4–S6). Such analysis revealed 848 genes, half of which are human (428; 50.5%) and half of which are murine (420; 49.5%), that displayed significant changes (≥1.5-fold change, adjusted p value < 0.05). As si-hSMAC-A is human specific, any effect on mouse gene expression must be mediated by the human tumor cells. Here, we only analyzed the altered expression of human genes in the tumor. The effect of silencing human SMAC/Diablo on the microenvironment of host mouse cells in the tumor is beyond the scope of the present study.

Figure 7.

Differentially Expressed Genes and Subcellular Morphological Alterations Induced by Reductions in SMAC/Diablo Levels

NGS data analysis showing selected downregulated (A) and upregulated (B) genes associated with the extracellular matrix, including cell-secreted collagen and proteoglycans, exosomes, and proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi lumen associated with vesicle formation. The number of genes and p values are indicated for each category. (C) Changes (as revealed by NGS) in the expression of genes associated with lipid transport, synthesis, and degradation in si-hSMAC-A-TTs, represented as fold change, relative to their expression in si-NT-TTs (means ± SEM, n = 3). (D) Representative electron microscopic images of si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-treated A549 xenograft sections. Arrows points to lamellar bodies. (E) The levels of PC and phospholipids (PL) in si-hSMAC-A-TTs, relative to si-NT-TTs (means ± SEM, n = 3), determined as described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods. (F) Changes in the expression of mRNA (qPCR) of enzymes associated with phosphatidylcholine synthesis in si-hSMAC-A-TTs, relative to si-NT, presented as fold change (means ± SEM, n = 3). (G) Schematic representation of diacylglycerols (a) and phosphatidylcholine synthesis (b and c) pathways, with down- and upregulated genes identified by arrows.

Of the human genes whose expression was modified following SMAC/Diablo silencing, 186 were upregulated and 242 were downregulated. Functional analysis (Gene Ontology system, DAVID) of gene expression in si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs revealed differential expression of genes associated with key functions and pathways related to tumorigenicity (Figure 7; Tables S4–S6). The major functional groups where changes were seen are presented below.

Genes Associated with Membranes, Organelles, and Extracellular Matrix

The expression of about 200 genes associated with cell membrane, exosomes, and extracellular matrix and proteins found in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi lumen were altered. While genes associated with cell membrane, extracellular exosomes and extracellular matrix were found to be both up- and downregulated, genes associated with the ER and Golgi lumen were only downregulated (Figures 7A and 7B; Table S4). Some of these results were validated by qPCR (Figure S8).

Genes Associated with Lipid Transport, Synthesis, and Regulation

Alterations in the membranal system could reflect that membrane components, such those involved in PL synthesis, were impaired upon SMAC/Diablo reduction. Indeed, si-hSMAC-A-TTs showed alterations in the expression levels of genes associated with the transport, synthesis, and regulation of lipids (Figure 7C; Table S5). These included the elongation of long chain fatty acids protein 4 (ELOV4;145-fold), ELOV3 (7-fold), and ATP10B (25-fold), which mediates the transport of PLs from the outer to the inner leaflet of various membranes, StARD10, involved in the transfer of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) between membranes, LIPH lipase, catalyzing the production of 2-acyl lysophosphatidic acid, and phospholipase C, cleaving PLs, that were all upregulated. At the same time, glycerol kinase (GK), diacylglycerol (DAG) kinase delta (DGKD), which phosphorylates DAG to produce phosphatidic acid, and acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACAD10), that participate in the beta-oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria, were all decreased in si-SMAC-TT (Figure 7C; Table S5). In addition, the expression of SLC44A4 that mediates choline transport was increased in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure S8A).

Genes Associated with Transporters of Metabolites and Ions and with Cell Metabolism

Another interesting group of differentially expressed genes includes those related to the transport of metabolites and ions (Figures S8A and S8B; Table S5). In si-hSMAC-A-TTs, downregulated genes included several members of the solute carrier family (SLC), which mediate sodium/bicarbonate and sodium/potassium/calcium co-transport, the organic anion transporter, which transports the prostaglandins PGD2, PGE1, PGE2, and the mitochondrial iron transporter. Other genes downregulated in si-hSMAC-A-TTs are associated with lung maturation, including sodium bicarbonate co-transporters (SLC4A4, NBC), and the sodium- and chloride-dependent glycine transporter 1 (SLC6A9).

Upregulated genes included the H+/sucrose symporter, genes involved in the regulation of lipid metabolism, the thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) transporter, a cation/proton anti-porter, and those encoding several channels for K+, Na+, and Cl− (Figure S8A; Table S5). Increased levels of anoctamin-1 (ANO1), a voltage-sensitive calcium-activated chloride channel that regulates trans-epithelial anion transport that is essential for lung airway physiology,30 of the Ca2+-activated potassium channel KCNN4, and of a two-pore potassium (K2P) channel KSNK1, which are involved in airway surface liquid hydration,31 were noted. The same is true for the epithelial Na+ channel (α-ENaC/SCNN1A), a critical factor during the perinatal period of lung development, involved in clearance of lung fluid.32

Metabolism-related genes whose expression was altered in sh-hSMAC-A-TTs included dehydrogenases and deaminases responsible for mediating the conversion of oxaloacetate to phosphoenolpyruvate, alcohol dehydrogenase, hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and adenosine deaminase, all of which were downregulated (Figure S8B; Table S5). Upregulated genes encoded for enzymes involved in nucleotide synthesis (cytidine deaminase, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase, calcium-activated nucleotidase 1), amino acid metabolism (peptidyl arginine deiminase, glutamic pyruvate transaminase), oligosaccharide biosynthesis, and protein glycosylation (glycosyltransferases, fucosyltransferases, beta-galactoside alpha-2,3-sialyltransferase, polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase) (Figure S8B; Table S5). Most of the transporters and metabolism-related proteins with modified expression in the si-hSMAC-A-TTs have already been reported to be associated with several cancers, in addition to the lung cancer analyzed here (Table S5).

Genes Associated with Inflammation and the Tumor Microenvironment

The si-hSMAC-A-TTs also showed a reduction in the expression of genes associated with inflammation and the tumor microenvironment, including cytokines, chemokines, their related receptors, and intracellular proteins associated with inflammatory and immune responses (Table S6). Selected results were confirmed by qPCR (Figure S8C). These included cytokine interleukin (IL)-6, known to be involved in tumorigenicity and the activation of transcription factors, such as STAT3, associated with oncogenicity.33 In addition, the results of NGS and qPCR analysis showed a reduction in the levels of nitric oxide synthase 1 (NOS1), an essential factor for tumorigenicity and angiogenesis, and of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) (Table S5; Figure S8C).34 Similar staining of si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs with the macrophage-specific F4/80 antibody was seen (Figure S8D).

A conclusion that can be drawn from these results is that upregulation of SMAC/Diablo expression in tumor cells may be associated with an increase in inflammatory activity that is essential for tumorigenicity, invasiveness, metastasis, and angiogenesis.

Ultrastructure and Lipid Synthesis in si-NT- and si-hSMAC-TTs

As SMAC/Diablo silencing resulted in morphological changes (Figure 4), we analyzed the subcellular ultrastructure of si-NT- and si-hSMAC-TTs using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figures 7D and S9A). In si-NT-TTs, a massive amount of intracellular vesicles of different sizes and densities, such as large vesicles containing surfactant-accumulating lamellar bodies and others, were seen. Such vesicles were not observed in the si-hSMAC-TTs (Figures 7D and S9A).

In addition, the major DNA form in the nucleus of cells in si-NT-TTs was darkly staining heterochromatin, while in si-SMAC-TTs, the DNA was mainly found as euchromatin and not readily stained (Figure 7D). Interestingly, euchromatin is prevalent in cells that are active in the transcription of many genes, while heterochromatin is most abundant in cells that are less active. This may be associated with cell differentiation processes. Moreover, the sizes of nuclei in si-hSMAC-A-TTs were almost twice those in si-NT-TTs (Figures 7D, S9A, and S9B; Table S1). The large nuclei in si-NT-TTs could result from membrane fluidity and/or osmolality changes, as reflected in the modified expression of transporters (Figure S8A; Table S5).

Finally, we analyzed the amounts of total PLs and specifically PC in si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TT lipid extracts (Figure 7E). Total PLs and PC levels were decreased by 47% and 37%, respectively, in si-hSMAC-A-TTs. These results are in agreement with the findings that SMAC/Diablo silencing resulted in alterations in the expression levels of genes associated with the transport, synthesis, and regulation of lipids (Figure 7C; Table S5). Therefore, using qPCR, we analyzed the levels of genes encoding enzymes associated with DAG synthesis, such as GK, and the mitochondrial proteins glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 1 and 4 (GPAM1, GPAM4). All were found to be decreased in si-SMAC-TTs (Figure 7F). In addition, levels of mRNA encoding enzymes involved in PC synthesis were also decreased (Figure 7F), whereas those encoding other enzymes associated with PC synthesis from PE, namely PE N-methyltransferase (PEMT), choline/ethanolamine kinase A (CHKA), and cholinephosphotransferase 1 (CHPT1), and phospholipase A2 (PLA2G1B), were increased. These results are presented in the PC and DAG synthesis pathways depicted in Figure 7G.

Discussion

The Paradox of Overexpression of the Pro-apoptotic Protein SMAC/Diablo in Cancer

We (Figure 1) and others16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 35 have demonstrated overexpression of SMAC/Diablo in many types of cancer. This is unexpected in view of the pro-apoptotic activity of the protein, which promotes caspase activation by binding IAPs.1, 2 We showed here that silencing SMAC/Diablo expression in various cell lines inhibited their growth, while in lung cancer xenografts, such expression inhibited tumor growth and resulted in the formation of glandular/alveoli-like morphological structures, indicative of cancer cell differentiation. These results reveal a novel non-apoptosis-related function for SMAC/Diablo in cancer associated with lipid synthesis. This function is essential for cancer cell growth and tumor development and thus may be a new target for cancer therapy.

As SMAC/Diablo is a promoter of cell death, we asked how cancer cells tolerate increased SMAC/Diablo expression and what benefits SMAC/Diablo overexpression offer cancer cells. Although the precise answers to these questions are unclear, as SMAC/Diablo is located in the mitochondria (Figure 6F), its death-inducing activity is prevented. Our data show that SMAC/Diablo is required for the growth of cancerous but not of non-cancerous cells in culture and for tumor growth. Moreover, our results directly implicate SMAC/Diablo as an important regulator of lipid transport and synthesis, as discussed below.

SMAC/Diablo-silencing resulted in reduction of Ki-67, a cellular marker of proliferation,36 both in culture (Figures 2I and 2J; Table S1) and in tumors (Figures 3F and 3G; Table S1). Ki-67 protein is detected during all cell cycle phases, other than resting G0 phase. During S phase, Ki-67 protein levels markedly increased, with these levels being maintained in interphase and M phase.37 In addition, cells treated with si-hSMAC were arrested in S phase, reflected by inhibition of BrdU incorporation and decreased DNA content in the si-hSMAC-TTs (Table S1). The presence of SMAC/Diablo in the nucleus and its function in PL synthesis (Figures 6B, 6C, and 6F; Table S1; discussed below) is in agreement with the observation that during the S phase, the levels of PLs inside the nucleus were reduced.38

SMAC/Diablo silencing in tumors resulted in widely altered expression of genes associated with the extracellular matrix, exosomes, and proteins in the ER and Golgi lumen associated with vesicle formation (Figures 7A, 7B, and 7D; Table S4). These changes may indicate a role for SMAC/Diablo in vesicular trafficking, exosome release, and extracellular matrix deposition. Exosome cargo can include factors serving as extracellular messengers, mediating cell-cell communication, and facilitating cancer progression and metastasis,39, 40 as well as those involved in regulating stromal activity and the cancer microenvironment. Indeed, SMAC/Diablo silencing also affected several factors associated with stromal activity (Figure 5; Table S4). si-hSMAC-A-TTs showed reduced expression of genes associated with inflammation, including cytokines, chemokines, and their related receptors, as well as intracellular proteins associated with inflammatory and immune responses (Table S6). Alterations in the expression of these genes are mainly associated with reduced tumorigenicity and invasiveness.

SMAC/Diablo silencing was also associated with modified expression of transporters of metabolites and ions and enzymes involved in metabolism (Figures S8A and S8B; Table S5). These include dehydrogenases and deaminases related to cholesterol, lipid, and nucleotide synthesis, amino acid metabolism, oligosaccharide biosynthesis, and protein glycosylation. Thus, the inhibition of cell and tumor growth may result from metabolic dysregulation. In this respect, most of the affected genes were reported to be associated with various cancers, and here, we showed the connection with lung cancer (Table S4).

Morphological Changes Leading to the Appearance of Glandular/Alveoli-like Structure in Tumors Silenced for SMAC/Diablo Expression

Morphological analysis of A549-derived tumor sections clearly demonstrated structural reorganization into glandular/alveoli-like clusters in si-hSMAC-A-TTs. Cancerous A549 cells are considered as AT2-like cells.28 AT2 cells are the main source for renewal of distal lung epithelium and may either regenerate into AT2 cells or differentiate into AT1 cells.24 The expression of the putative AT1 cell marker podoplanin24 and alterations in cell morphology to present elongated nuclei in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figures 4D and 4E) support the notion that A549 AT2-like cells undergo differentiation into AT1 cells upon reduction of SMAC/Diablo expression. Moreover, these AT1-like cells were arranged in the periphery of alveoli-like structure in close to the endothelial cells visualized by CD31 staining (Figure 4G). In contrast, the organization of endothelial cells in si-NT-TTs typically reflected ongoing tumor angiogenesis. These findings suggest that reduction in of SMAC/Diablo expression triggered AT2 differentiation into AT1 cells and to morphological reorganization into lung alveoli-like structures (Figure 4H).

Cancer progression is associated with stromal activity,41 characterized by increased deposition of collagen isoforms, laminin and fibronectin, and heparan-sulfate production, as well as of extracellular matrix (ECM) degradative enzymes and metalloproteinases (MMPs). Reduction of SMAC/Diablo levels in tumors also altered stromal formation (Figure 5). As expected for tumors, si-NT-TTs showed a thin network, dispersed throughout the tumor and enriched with vascular formations, with both supporting tumor development (Figures 5A and 5B). On the other hand, massive fibrotic structures, resembling scar tissue, were found in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure 5A). These stromal structural differences between SMAC/Diablo expressing and non-expressing tissues may result from decreased expression of α-SMA, a CAF marker (Figure 5E). These, along with fibroblast activity (as revealed by vimentin and Sirus red staining), indicate a non-cancerous stromal activity in si-hSMAC-TTs, such as wound healing scar formation.

Finally, ultrastructural analysis of si-NT- and si-hSMAC-A-TTs clearly demonstrated marked changes in intracellular organelles, including the nucleus (Figures 7D and S9). These changes included decreases in intracellular vesicles of different sizes and densities, such surfactant-accumulating lamellar bodies and other vesicle types, in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figures 7D and S9). Lamellar bodies are secretory organelles found in AT2 cells that store pulmonary surfactant and are composed of 60%–70% PC.42 As discussed below, our results suggest that the morphological changes observed in si-hSMAC-A-TTs are associated with SMAC/Diablo function in PL synthesis.

SMAC/Diablo Overexpression in Cancer Regulates Lipid Synthesis

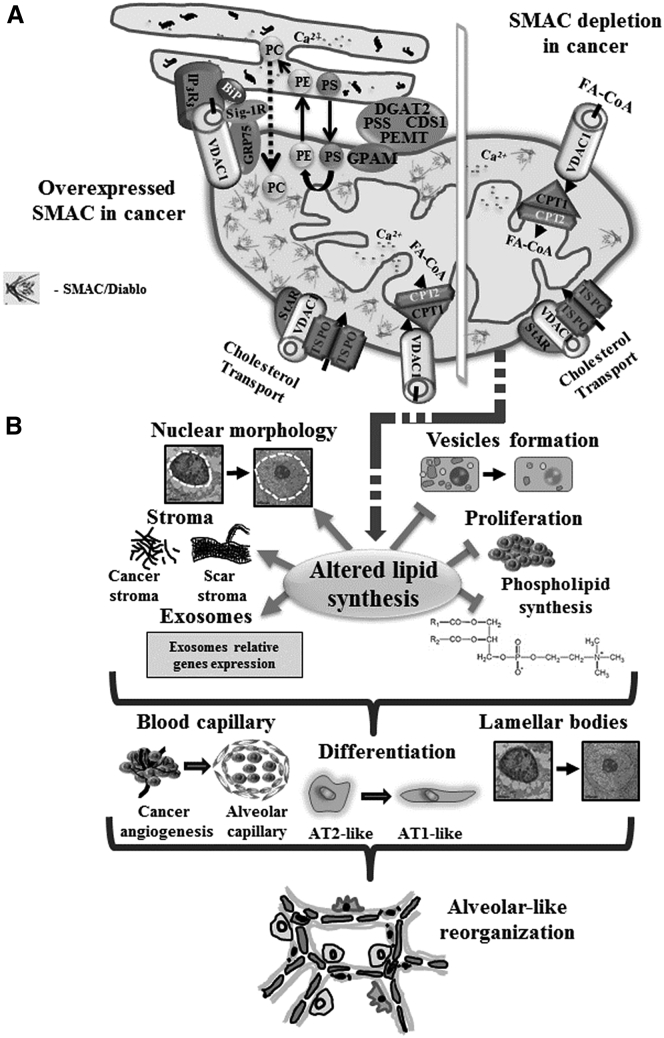

Our results show that the expression levels of many genes associated with the formation of vesicles mediating intra- and extra-cellular transport and related to organelles, such as the ER and Golgi, and of exosomes were modified (Figures 7A and 7B; Table S4). In addition, the expression levels of genes encoding several enzymes associated with cholesterol and lipid transport, synthesis, degradation, and regulation, were modified (Figures 7C and 7F). These included StARD10, related to lipid transfer, LIPH lipase, phospholipase C, acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase, ELOV4 and ELOV3, and ATP10B (P4-ATPase), a PL flippase that can alter cell shape and which inhibits cell adhesion and spreading, and thus may be associated with the morphological changes induced by SMAC/Diablo silencing. Moreover, analysis of PL and specifically, of PC content, showed a significant decrease (40%–50%) in si-hSMAC-A-TTs, relative to si-NT-TTs (Figure 7E). PC is synthesized via two major distinct pathways, the de novo or cytidine diphosphate (CDP)-choline (Kennedy) pathway, and the PE methyl transferase (PEMT) pathway, involving triple methylation of PE carried out by a single enzyme, PEMT.43 The enzymes involved in PC biosynthesis are located at the mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs), where transport between the ER and mitochondria takes place (Figure 8). Our results show a decrease in the expression of key enzymes in the Kennedy pathway, and increased PEMT expression (Figure 7G). SMAC/Diablo at the IMS may affect PL synthesis via the phosphatidylserine decarboxylase (PISD), an inner mitochondrial membrane enzyme facing the IMS. PISD catalyzes the conversion of PS to PE with the release of CO2,44 upon which PE is converted to PC in the ER (Figure 8). In this respect, a connection between mitochondrial lipid metabolism and the differentiation program of breast cancer cells, involving modulation of synthesis of mitochondrial PE, has been recently presented.45

Figure 8.

Schematic Representation of the Effects of SMAC/Diablo Depletion on Tumor Morphology and Properties

(A) A schematic representation of mitochondria in lung cancer cells is provided, with proposed functions of overexpressed SMAC/Diablo in the regulation and maintenance of phospholipid synthesis highlighted. The major site of phospholipid synthesis is at ER-mitochondria contact sites (MAM), shown with key proteins indicated. These include the inositol 3 phosphate receptor type 3 (IP3R3), the sigma 1 receptor (Sig1R) (a reticular chaperone), binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP), the ER HSP70 chaperone, glucose-regulated protein 75 (GRP75), and others.55 Key enzymes of lipid biosynthesis, such as diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2 (DGAT2), phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT), phosphatidyl serine synthase (PSS), and phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase 1 (CDS1), are all present in high concentrations at MAMs,56, 57 indicating a role for this structure in lipid biosynthesis and trafficking. Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 1, mitochondrial (GPAM), is located in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM) at the MAM. Phosphatidylserine (PS) is produced in the ER but needs to be transferred to the mitochondria, where it is converted into phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). PE is then translocated back to the ER, where it is converted into phosphatidylcholine (PC). Also indicated are the transfer of acyl-CoA across the OMM via VDAC1 to the IMS, where they are converted into acylcarnitine by CPT1a for further processing by β-oxidation, and the cholesterol transport complex composed of Star, VDAC1, and TSPO. (B) SMAC/Diablo depletion using specific si-SMAC leads to a decrease in vesicle formation and inhibition of cell proliferation and phospholipid synthesis. SMAC/Diablo depletion also alters nuclear morphology, stromal structure, and cancer microenvironment, and the expression of genes associated with the cell membrane, exosomes, and ER- and Golgi-related proteins. These lead to changes in blood capillary organization, AT2-like cells’ differentiation into AT1-like cells, and reduced lamellar body formation. Finally, these alterations lead to morphological changes reflected in the formation of glandular/alveoli-like structures.

Another important finding is the decrease in SLC44A4 expression in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figure S8A). SLC44A4 is found in both the plasma and mitochondrial membranes, where it transports choline with high affinity in a Na+-independent manner.46 SLC44A4 supplies choline for the synthesis of PC. Therefore, SLC44A4 is physiologically relevant for membrane synthesis during cell growth or repair, and given its role in PL production, for the generation of lung surfactants. Enhanced choline transport was reported in cancer cells, where it was proposed to play a role in the elevation of PC. Indeed, enhancement of total choline levels is one of the most widely established characteristics of cancer cells.47 The aberrant choline metabolism seen in cancer cells is strongly correlated with their malignant progression.48 Accordingly, members of the SLC44 family were proposed as novel molecular targets for cancer therapy.46 In cancer, in addition to increased cellular transport of choline, there is often increased expression of choline kinase (CK), and hence, increased phosphorylation of choline.49 All of these enzymes and transporters were downregulated in si-hSMAC-A-TTs (Figures 7F and S8A).

SMAC/Diablo Nuclear Localization and Effects of Its Depletion on Nuclear Structure, Division, and Function

The presence of PLs in chromatin and the nuclear matrix and the roles of nuclear PLs in the structural organization of chromatin and nucleic acid synthesis have been demonstrated.50 As intra-nuclear PLs regulate DNA replication,38 changes seen in the expression of many genes upon silencing SMAC/Diablo expression (Tables S4–S6) may result from the decrease in PL levels in the cell (Figure 7; Table S1) and thus, in the nucleus. Further studies are required to evaluate the relationship between high SMAC/Diablo expression levels in cancer and its function in regulating nuclear PL levels and their regulation of DNA replication.38

Interestingly, SMAC/Diablo has been shown to interact with two nuclear proteins, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), also known as the oxygen-independent β subunit of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1β) and the Mastermind-like transcriptional co-activator MAML2.51 To execute their transcriptional function, HIFs must form a heterodimer between an oxygen-dependent α subunit (HIF-1α or HIF-2α) and an oxygen-independent subunit (HIF-1β). The HIF-2α-ARNT dimer is involved in cellular adaptation to the oxygen stress related to tumor growth and progression. ARNT also is required for nuclear localization of the transcriptional repressors NPAS1 and NPAS3.52 MAML2, as a transcriptional co-activator, plays an important role in Notch signaling, regulating multiple developmental pathways.53 MAML2 binds to proteins as a cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP).

Thus, as nuclear SMAC/Diablo binds HIF-1β (ARNT) and MAML2, it may compete with HIF-1α, HIF-2α, NPAS1, or NPAS3 binding to ARNT. Similarly, by binding MAML2, SMAC/Diablo interferes with interactions of MAML2 with CBP. These effects of SMAC/Diablo were diminished upon silencing SMAC/Diablo expression. This, together with SMAC/Diablo-mediated regulation of PL synthesis and given how nuclear PLs control nuclear structure and function, explains why silencing SMAC/Diablo expression would affect multiple signaling pathways.

The novel findings presented in this study, showing that reduced SMAC/Diablo expression in cancer cells leads to changes in the expression of genes associated with the cell membrane, vesicle formation, ER- and Golgi-related proteins, cell ultrastructure, and PL transport and synthesis, are integrated and presented in a schematic model (Figure 8). In summary, the results presented here show that SMAC/Diablo, overexpressed in many cancers, performs additional non-apoptotic function(s) contributing to cancer cell survival. Reducing SMAC/Diablo expression inhibited the growth of cancer cells, both in culture and in tumors. Moreover, residual si-SMAC-treated lung tumors showed tissue reorganization, with the formation of alveolar-like structures, upon differentiation of the AT2-like tumor cells into AT1-like cells. It appears as if SMAC/Diablo silencing leads to the reactivation of “memories” of physiological and morphological features of alveoli, including reorganization of the host endothelial cells (Figures 4F and S6). The hundreds of genes shown to be differentially expressed in si-hSMAC-TTs are associated with a wide variety of cellular and tissue morphological traits and functions, indicative of the non-apoptotic functions of SMAC/Diablo, essential for tumorigenesis.

Considering that large fractions of patients are insensitive to various therapies, including targeted therapies, such as immunotherapy and angiogenesis inhibition,54 developing novel therapeutic strategies is a crucial need. The role of SMAC/Diablo in the PL synthesis that is vital for cancer cell growth and function is thus a potential target for the development of new therapeutic approaches for cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

See the Supplemental Materials and Methods for detailed experimental procedures.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Thirteen cell lines representing different cancers and five non-cancerous cell lines or primary cultures were grown in the appropriate medium and maintained in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2, as described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods. Human SMAC/Diablo-specific siRNA (si-hSMAC-A; sense 5′-AAGCGGUGUUUCUCAGAATTGtt-3′ and anti-sense 5′-AACAAUUCUGAGAAACCCGCtt-3′) and three other SMAC/Diablo-targeting siRNAs (B–D), as well as non-targeting siRNA (si-NT) were designed (see Supplemental Materials and Methods) and synthesized by Genepharma (Suzhou, China). Cells were seeded (150,000 cells/well) in 6-well culture plates, cultured to 40%–60% confluence, and transfected with 10–100 nM si-NT or si-hSMAC using the JetPRIME transfection reagent (Illkirch, France), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

SRB Cell Proliferation Assay

Twenty-four hours post-transfection with si-NT or si-hSMAC, cells (10,000/well) were counted and seeded in 96-well plates. After an additional 48, 72, or 96 hr, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 10% trichloroacetic acid, and stained with SRB. SRB was extracted from the cells using 100 mM Tris-base, and absorbance at 510 nm was determined using an Infinite M1000 plate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Xenograft Experiments

Lung cancer A549 (3 × 106) or breast cancer MDA-MB231 (3 × 106) cells were s.c. inoculated into the hind leg flanks of 6-week-old athymic male nude mice. When the tumor volume reached 75–90 mm3, the mice were randomized into 2 or 3 groups and treated with si-NT or si-hSMAC mixed with JetPEI reagent, which was injected into the established s.c. tumors (350 or 700 nM, final concentration) every 3 days. At the end of the experiments, the mice were sacrificed and the tumors were excised and processed for IHC or frozen in liquid nitrogen for immunoblotting and RNA isolation, as described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods. Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

IHC, Immunofluorescence, and Immunoblotting

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of si-NT- or si-hSMAC-TTs were stained with H&E or probed with appropriate antibodies by IHC or immunofluorescent staining (see Supplemental Materials and Methods).

TUNEL Assay

Fixed tumor sections were processed for a TUNEL assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (see Supplemental Materials and Methods).

Lipid Extraction and Analysis

Lipid extractions from si-NT-TTs and si-SMAC-TTs and quantitative analyses of PLs and PC were carried out as described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

RNA Preparation, qPCR, and NGS

Total RNA was isolated from si-NT- or si-hSMAC-A-TTs, and the cDNA generated was subjected to NGS analysis or qPCR as described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Patient-Derived Samples

CLL blood samples were obtained from Soroka University Medical Center from patients not receiving any treatment, while PBMCs were isolated as described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods. Fresh cancerous and non-cancerous lung tissue, specimens were obtained from the same lung cancer patients and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen until analyzed for SMAC/Diablo expression. The studies were approved by the Soroka University Medical Center Advisory Committee.

Statistics and Data Analysis

Statistical significance is reported at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, or ***p < 0.001.

Author Contributions

A.P., T.A., Y.K., and R.J. designed and performed the research and analyzed the data; V.S.-B. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Israel Science Foundation (307/13) and by Phil and Sima Needleman and Yafa and Ezra Yerucham research funds. We thank the Genomics unit at the Grand Israel National Center for Personalized Medicine (G-INCPM) for their assistance with library preparation and sequencing and the Bioinformatics Core Facility at the National Institute for Biotechnology in the Negev, Ben-Gurion University.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Materials and Methods, nine figures, and six tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.12.020.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Verhagen A.M., Ekert P.G., Pakusch M., Silke J., Connolly L.M., Reid G.E., Moritz R.L., Simpson R.J., Vaux D.L. Identification of DIABLO, a mammalian protein that promotes apoptosis by binding to and antagonizing IAP proteins. Cell. 2000;102:43–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du C., Fang M., Li Y., Li L., Wang X. Smac, a mitochondrial protein that promotes cytochrome c-dependent caspase activation by eliminating IAP inhibition. Cell. 2000;102:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng Y., Lin Y., Wu X. TRAIL-induced apoptosis requires Bax-dependent mitochondrial release of Smac/DIABLO. Genes Dev. 2002;16:33–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.949602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiozaki E.N., Shi Y. Caspases, IAPs and Smac/DIABLO: mechanisms from structural biology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:486–494. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verhagen A.M., Vaux D.L. Cell death regulation by the mammalian IAP antagonist Diablo/Smac. Apoptosis. 2002;7:163–166. doi: 10.1023/a:1014318615955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chai J., Du C., Wu J.W., Kyin S., Wang X., Shi Y. Structural and biochemical basis of apoptotic activation by Smac/DIABLO. Nature. 2000;406:855–862. doi: 10.1038/35022514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi H., Bhalla K., Wang H.G. Bax plays a pivotal role in thapsigargin-induced apoptosis of human colon cancer HCT116 cells by controlling Smac/Diablo and Omi/HtrA2 release from mitochondria. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1483–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X.D., Borrow J.M., Zhang X.Y., Nguyen T., Hersey P. Activation of ERK1/2 protects melanoma cells from TRAIL-induced apoptosis by inhibiting Smac/DIABLO release from mitochondria. Oncogene. 2003;22:2869–2881. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chauhan D., Li G., Hideshima T., Podar K., Mitsiades C., Mitsiades N., Munshi N., Kharbanda S., Anderson K.C. JNK-dependent release of mitochondrial protein, Smac, during apoptosis in multiple myeloma (MM) cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17593–17596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adrain C., Creagh E.M., Martin S.J. Apoptosis-associated release of Smac/DIABLO from mitochondria requires active caspases and is blocked by Bcl-2. EMBO J. 2001;20:6627–6636. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts D.L., Merrison W., MacFarlane M., Cohen G.M. The inhibitor of apoptosis protein-binding domain of Smac is not essential for its proapoptotic activity. J. Cell Biol. 2001;153:221–228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Ruiz G.U., Victoria-Acosta G., Vazquez-Santillan K.I., Jimenez-Hernandez L., Muñoz-Galindo L., Ceballos-Cancino G., Maldonado V., Melendez-Zajgla J. Ectopic expression of new alternative splice variant of Smac/DIABLO increases mammospheres formation. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014;7:5515–5526. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimshaw M.J., Cooper L., Papazisis K., Coleman J.A., Bohnenkamp H.R., Chiapero-Stanke L., Taylor-Papadimitriou J., Burchell J.M. Mammosphere culture of metastatic breast cancer cells enriches for tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R52. doi: 10.1186/bcr2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okada H., Suh W.K., Jin J., Woo M., Du C., Elia A., Duncan G.S., Wakeham A., Itie A., Lowe S.W. Generation and characterization of Smac/DIABLO-deficient mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:3509–3517. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3509-3517.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kashkar H., Seeger J.M., Hombach A., Deggerich A., Yazdanpanah B., Utermöhlen O., Heimlich G., Abken H., Krönke M. XIAP targeting sensitizes Hodgkin lymphoma cells for cytolytic T-cell attack. Blood. 2006;108:3434–3440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bao S.T., Gui S.Q., Lin M.S. Relationship between expression of Smac and Survivin and apoptosis of primary hepatocellular carcinoma. HBPD INT. 2006;5:580–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arellano-Llamas A., Garcia F.J., Perez D., Cantu D., Espinosa M., De la Garza J.G., Maldonado V., Melendez-Zajgla J. High Smac/DIABLO expression is associated with early local recurrence of cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:256. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shintani M., Sangawa A., Yamao N., Kamoshida S. Smac/DIABLO expression in human gastrointestinal carcinoma: association with clinicopathological parameters and survivin expression. Oncol. Lett. 2014;8:2581–2586. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kempkensteffen C., Hinz S., Christoph F., Krause H., Magheli A., Schrader M., Schostak M., Miller K., Weikert S. Expression levels of the mitochondrial IAP antagonists Smac/DIABLO and Omi/HtrA2 in clear-cell renal cell carcinomas and their prognostic value. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2008;134:543–550. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoo N.J., Kim H.S., Kim S.Y., Park W.S., Park C.H., Jeon H., Jung E.S., Lee J.Y., Lee S.H. Immunohistochemical analysis of Smac/DIABLO expression in human carcinomas and sarcomas. APMIS. 2003;111:382–388. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2003.t01-1-1110202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao P., Fu J.L., Yao B.Y., Jia Y.R., Zhou Z.C. S phase cell percentage normalized BrdU incorporation rate, a new parameter for determining S arrest. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2014;27:215–219. doi: 10.3967/bes2014.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason R.J. Biology of alveolar type II cells. Respirology. 2006;11(Suppl):S12–S15. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fehrenbach H. Alveolar epithelial type II cell: defender of the alveolus revisited. Respir. Res. 2001;2:33–46. doi: 10.1186/rr36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barkauskas C.E., Cronce M.J., Rackley C.R., Bowie E.J., Keene D.R., Stripp B.R., Randell S.H., Noble P.W., Hogan B.L. Type 2 alveolar cells are stem cells in adult lung. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:3025–3036. doi: 10.1172/JCI68782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotton D.N., Fine A. Lung stem cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;331:145–156. doi: 10.1007/s00441-007-0479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rock J.R., Hogan B.L. Epithelial progenitor cells in lung development, maintenance, repair, and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011;27:493–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anversa P., Kajstura J., Leri A., Loscalzo J. Tissue-specific adult stem cells in the human lung. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1038–1039. doi: 10.1038/nm.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mao P., Wu S., Li J., Fu W., He W., Liu X., Slutsky A.S., Zhang H., Li Y. Human alveolar epithelial type II cells in primary culture. Physiol. Rep. 2015;3:e12288. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kubo N., Araki K., Kuwano H., Shirabe K. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6841–6850. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rock J.R., O’Neal W.K., Gabriel S.E., Randell S.H., Harfe B.D., Boucher R.C., Grubb B.R. Transmembrane protein 16A (TMEM16A) is a Ca2+-regulated Cl- secretory channel in mouse airways. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:14875–14880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao K.Q., Xiong G., Wilber M., Cohen N.A., Kreindler J.L. A role for two-pore K+ channels in modulating Na+ absorption and Cl− secretion in normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2012;302:L4–L12. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00102.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustafa S.B., Isaac J., Seidner S.R., Dixon P.S., Henson B.M., DiGeronimo R.J. Mechanical stretch induces lung α-epithelial Na(+) channel expression. Exp. Lung Res. 2014;40:380–391. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2014.934410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dutta P., Sabri N., Li J., Li W.X. Role of STAT3 in lung cancer. JAK-STAT. 2015;3:e999503. doi: 10.1080/21623996.2014.999503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Augsten M., Sjöberg E., Frings O., Vorrink S.U., Frijhoff J., Olsson E., Borg Å., Östman A. Cancer-associated fibroblasts expressing CXCL14 rely upon NOS1-derived nitric oxide signaling for their tumor-supporting properties. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2999–3010. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibata T., Mahotka C., Wethkamp N., Heikaus S., Gabbert H.E., Ramp U. Disturbed expression of the apoptosis regulators XIAP, XAF1, and Smac/DIABLO in gastric adenocarcinomas. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 2007;16:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.pdm.0000213471.92925.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scholzen T., Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J. Cell. Physiol. 2000;182:311–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruno S., Darzynkiewicz Z. Cell cycle dependent expression and stability of the nuclear protein detected by Ki-67 antibody in HL-60 cells. Cell Prolif. 1992;25:31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1992.tb01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maraldi N.M., Santi S., Zini N., Ognibene A., Rizzoli R., Mazzotti G., Di Primio R., Bareggi R., Bertagnolo V., Pagliarini C. Decrease in nuclear phospholipids associated with DNA replication. J. Cell Sci. 1993;104:853–859. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.3.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujita Y., Yoshioka Y., Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicle transfer of cancer pathogenic components. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:385–390. doi: 10.1111/cas.12896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Minciacchi V.R., Freeman M.R., Di Vizio D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;40:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dvorak H.F. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parra E., Pérez-Gil J. Composition, structure and mechanical properties define performance of pulmonary surfactant membranes and films. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2015;185:153–175. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs R.L., Zhao Y., Koonen D.P., Sletten T., Su B., Lingrell S., Cao G., Peake D.A., Kuo M.S., Proctor S.D. Impaired de novo choline synthesis explains why phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase-deficient mice are protected from diet-induced obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22403–22413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vance J.E., Steenbergen R. Metabolism and functions of phosphatidylserine. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005;44:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keckesova Z., Donaher J.L., De Cock J., Freinkman E., Lingrell S., Bachovchin D.A., Bierie B., Tischler V., Noske A., Okondo M.C. LACTB is a tumour suppressor that modulates lipid metabolism and cell state. Nature. 2017;543:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nature21408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inazu M. Choline transporter-like proteins CTLs/SLC44 family as a novel molecular target for cancer therapy. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2014;35:431–449. doi: 10.1002/bdd.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Glunde K., Serkova N.J. Therapeutic targets and biomarkers identified in cancer choline phospholipid metabolism. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:1109–1123. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.7.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glunde K., Jacobs M.A., Bhujwalla Z.M. Choline metabolism in cancer: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2006;6:821–829. doi: 10.1586/14737159.6.6.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glunde K., Bhujwalla Z.M., Ronen S.M. Choline metabolism in malignant transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:835–848. doi: 10.1038/nrc3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alessenko A.V., Burlakova E.B. Functional role of phospholipids in the nuclear events. Bioelectrochemistry. 2002;58:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5394(02)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J., Huo K., Ma L., Tang L., Li D., Huang X., Yuan Y., Li C., Wang W., Guan W. Toward an understanding of the protein interaction network of the human liver. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:536. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teh C.H., Lam K.K., Loh C.C., Loo J.M., Yan T., Lim T.M. Neuronal PAS domain protein 1 is a transcriptional repressor and requires arylhydrocarbon nuclear translocator for its nuclear localization. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:34617–34629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604409200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McElhinny A.S., Li J.L., Wu L. Mastermind-like transcriptional co-activators: emerging roles in regulating cross talk among multiple signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2008;27:5138–5147. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arbiser J.L., Bonner M.Y., Gilbert L.C. Targeting the duality of cancer. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2017;1:23. doi: 10.1038/s41698-017-0026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Filadi R.Z.E., Pozzan T., Pizzo P., Fasolato C. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria connections, calcium cross-talk and cell fate: a closer inspection. In: Agostinis P., Afshin S., editors. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Health and Disease. Springer; 2012. pp. 75–106. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Flis V.V., Daum G. Lipid transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013;5:a013235. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schenkel L.C., Bakovic M. Formation and regulation of mitochondrial membranes. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2014;2014:709828. doi: 10.1155/2014/709828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.