Abstract

Two cases of a high-riding innominate artery, which were found during routine surgical tracheostomy. A cartilage flap was applied to cover the significant vessel to prevent the life-threatening complications. These two cases were followed up for 2 months without any adverse events. We discussed the related vascular anatomy, imaging studies and brief literature review.

Keywords: ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology; head and neck surgery; otolaryngology / ent; intensive care; emergency medicine

Background

Tracheostomy is a standard procedure in head and neck surgery and emergency medicine to secure a patient’s airway. It is quite rare to find brachiocephalic trunk extraordinarily high and directly in front of the trachea during surgical tracheostomy. Surgeons should always be aware of anatomical variants of the branches of the aortic arch, especially the high-riding innominate artery. Some of the life-threatening complications are the intraoperative bleeding or late complication, such as trachea-innominate artery fistula (TIF). In such cases, preventive techniques should be followed, such as avoiding low tracheal incision and hyperinflation of the tracheostomy tube cuff. One of the ways of minimising complications is creating a flap to protect the vessel.

Case presentation

Case 1

This was an 84-year-old woman with multiple medical problems who was admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) for recurrent aspiration pneumonia. During 3 weeks of endotracheal intubation, numerous weaning attempts failed. During a preoperative clinical examination for surgical tracheostomy, a notable pulsation was detected in the midline of lower neck. In addition, in a previous CT scan of chest with contrast, we found a high-riding innominate artery (figure 1). During the surgery, the innominate artery was seen in high position covering the site of tracheal incision between the second and the third tracheal rings (figure 2). We dissected the trachea from the cranial to the caudal aspect by lateralising the brachiocephalic trunk (video 1). In order to increase the distance between the tracheostomy site and the brachiocephalic trunk, we created a cartilage flap which was taken from the anterior wall of the trachea on the right side based (like a book). This flap was stitched with skin on the right side to protect the artery.

Figure 1.

Case 1. Axial chest CT scan with contrast showing the brachiocephalic trunk just in front of the trachea. B, brachiocephalic trunk; C, Lt common carotid artery; SC, Lt subclavian artery; T, trachea.

Figure 2.

Case 1. During the surgery, the brachiocephalic trunk was encountered in front of the trachea and completely cover the tracheostomy level between second and third tracheal rings. B, brachiocephalic trunk; T, trachea.

Video 1.

Case 1. During the surgery, after dissection the trachea and lateralising the brachiocephalic trunk.

Case 2

This was a 94-year-old woman with chronic respiratory failure who was admitted to ICU and ventilated for more than 4 weeks. Clinical examination prior to surgical tracheostomy revealed the same pulsation in the same site as we found in the first case. A chest CT scan also showed high-riding innominate artery (figure 3). This case happened only 1 week after we operated on the first case; therefore, all the same precautions were taken and the procedure was done by placing a cartilage flap (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Case 2. Sagittal chest CT scan with contrast showing the brachiocephalic trunk just in front of the trachea and reached to the first three tracheal rings. AA, aortic arch; B, brachiocephalic trunk; T, trachea.

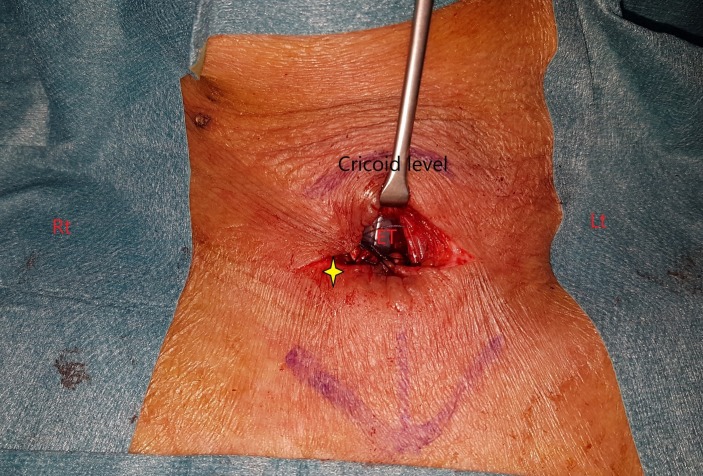

Figure 4.

Case 2. After tracheostomy. Yellow star indicates the cartilage flap which was taken from the anterior wall of the trachea then stitched with the skin on the right side. ET, endotracheal tube.

Investigations

Both patients already had chest CT scans done prior to our assessment; therefore, there was no need for further radiology investigation before surgery. However, a CT scan of the neck with contrast would be the best option in showing the overall image of high-riding innominate artery.

Outcome and follow-up

Patients had been followed up for 2 months without any surgical complications.

Discussion

The most frequent surgical intervention performed by ENT surgeons in ICU patients would be the surgical tracheostomy for those with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Many of these ICU patients will have complex medical problems requiring long-term, high-dependency care. Surgical tracheostomy for ICU patients is generally regarded as a minor surgical procedure, although with rare complications.

Holmgren has emphasised that open tracheostomy is the safest way to stabilise the airway,1 but there are also several methods of percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy that cause less damage to the surrounding tissues.2 The disadvantages of percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy are a lack of a clear view of the tissues and the difficulty of surgical intervention in case of severe bleeding. The brachiocephalic (innominate) artery is the largest branch of the arch of the aorta. It runs posterior to the centre of the manubrium sternum, across the trachea from left to right, lying at first in front of the trachea and then on its right side. It divides at the level of the right sternoclavicular joint into the right common carotid and the right subclavian arteries.3

Usually, the brachiocephalic trunk is located on the right side of the trachea and the left common carotid artery is on the left,4 but during tracheostomy, these vessels should not be encountered. In children, the brachiocephalic trunk may be found higher up, which can result in complications during surgical tracheostomy.4 Conoyer described a cadaveric case in which the right common carotid artery crossed the midline neck anterior to the trachea,5 and Lterezote showed another one in which the brachiocephalic trunk lay in front of it.6 They emphasised that such anatomical variants could have severe consequences in operations on the anterior neck if the surgeon was not aware of them. In 1879, Korte reported the first patient in whom a tracheostomy was complicated by erosion of a major blood vessel. The brachiocephalic artery is the most commonly eroded vessel.7 Bleeding can also occur from the carotid artery, brachiocephalic vein and the aortic arch.8 9

In our patients, we had to be aware of the potentially life-threatening complication of massive haemorrhage because of the unusual position of their brachiocephalic trunk.

TIF is a life-threatening late complication of tracheostomy that usually presents itself with acute and massive tracheal bleeding. The pathomechanism of TIF is thought to be pressure necrosis by the elbow, tip or highly inflated cuff of tracheostomy tubes. High-riding innominate artery is believed to be at significant risk of TIF when the artery is compressed by the elbow of the tracheostomy tube. Without prompt surgical intervention, the outcome of this complication is grave. Therefore, a high index of suspicion should be maintained in any patient with tracheostomy and subsequent haemoptysis.10 Premonitory minimal tracheal bleeding and pulsation of the tracheostomy tube synchronous with the heartbeats have been reported as warning signs of massive haemorrhage from TIF.11 12 However, pulsation of the tracheostomy tube has been noted in only 5% of patients who were later found to have had a TIF.13 Approximately, 50% of patients with TIF have relatively minor bleeding that stops spontaneously before the diagnosis.13 When TIF is suspected, the patient must be immediately transported to the operation room (OR), and careful fibreoptic bronchoscopy should be performed simultaneously with slow cuff deflation, followed by gradual withdrawal of the tracheostomy tube. Cooper,14 however, suggested that rigid rather than fibreoptic bronchoscopy should be performed, not only to examine the source of bleeding but also to control against possible sudden haemorrhage by compressing the bleeding innominate artery against the sternum. Angiography is rarely helpful, is not recommended and may delay definitive diagnosis and treatment.15 If brisk haemorrhage occurs, tracheostomy tube cuff hyperinflation as a first step may temporarily control the bleeding.13 When the suspicion of a fistula is high, an orotracheal tube should be inserted with the intent to advance it distally past the tracheostomy site and TIF, while simultaneously removing the tracheostomy tube. This manoeuvre will secure the airway in the case of sudden bleeding, which could make visualisation for placement of the endotracheal tube difficult. This will also provide an airway during diagnostic bronchoscopy. If overinflation of the tracheostomy tube cuff or endotracheal tube cuff as a first manoeuvre fails to control the bleeding, the orotracheal tube should be positioned distal to the bleeding site, and digital compression of the innominate artery through the tracheostomy tract must be performed.16 With an index finger inserted through the tracheostomy tract in the pretracheal fascial plane, the innominate artery must be bluntly dissected from the trachea and compressed against the sternum. This digital compression should be maintained during transport of the patient to the OR until surgical control of the bleeding is accomplished. Although this manoeuvre is only a temporary measure, it successfully stops bleeding in approximately 90% of patients.13 However, immediate surgical repair is the only life-saving procedure.10

During a review of the literature, Bjork flap was found to be an excellent manoeuvre to protect the high-riding innominate artery. The manoeuvre consists of suturing an inverted U-shaped flap of the trachea to the skin edge.17 In this way, we cover the vessel and protect it from the tracheostomy tube pressure and make space between the trachea and the artery. In our two cases, the innominate artery was mainly seen in lateral location to the trachea; therefore, we modified this flap partially by changing its base to the right side, so that it covered the vessel completely.

Imaging studies to evaluate the brachiocephalic (innominate) artery, specifically CT angiography, ultrasonography and MR angiogram of the neck and upper chest, are indicated when there is any suspected anomaly especially vascular one such as a high-riding innominate artery. This anatomical variant is presumed in cases where there is a notable pulsation at the anterior lower neck. This sign indicates a vascular malformation. However, not all patients can undergo preoperative imaging study. Depending on circumstances, surgeons would be forced to perform tracheostomy without any imaging study. Therefore, these kind of major vessel variations are extremely important as potential risk for tracheostomy in any situation. If potential risk is recognised, even digital examination during operation can enable to detect anomaly of major vessels.

Learning points.

Surgical tracheostomy is not always a safe procedure.

Imaging studies to evaluate any vascular anomalies should be considered before surgical tracheostomy, when there are suspected clinical signs such as a notable pulsation at the anterior lower neck.

During the surgical tracheostomy, when unusual vessels are encountered, we must protect them by creating various types of flaps (cartilage, muscle and/or thyroid) to avoid further complications such as an erosion of these vessels by the pressure of a tracheostomy tube.

Footnotes

Contributors: H.A.Dalati is the surgeon and is responsible for the planning, reporting and follow-up of the cases. M.S.Jabbr was responsible for reporting and design. J.Kassouma reviewed the study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Holmgren EP, Bagheri S, Bell RB, et al. Utilization of tracheostomy in craniomaxillofacial trauma at a level-1 trauma center. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;65:2005–10. 10.1016/j.joms.2007.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mieth M, Schellhaaß A, Hüttner FJ, et al. Tracheotomietechniken. Der Chirurg 2016;87:73–85. 10.1007/s00104-015-0116-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warwick R, Williams PL. Gray’s anatomy. 35th Br. edn Philadelphia: Saunders, 1973;1:443–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang J. Klinische anatomie der halswirbelsäule: 13 tabellen. Thieme, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conoyer BM, Varvares MA, Cooper MH. Right common carotid artery crossing the midline neck anterior to the trachea: a cadaver case report. Head Neck 2008;30:1253–6. 10.1002/hed.20765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iterezote AM, Medeiros AD, Barbosa Filho RC, et al. Variación anatómica del tronco braquicefálico y arteria carótida común en disecciones de cuello. Int J Morphol 2009;27:601–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silen W, Spieker D. Fatal hemorrhage from the innominate artery after tracheostomy. Ann Surg 1965;162:1005–12. 10.1097/00000658-196512000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brantigan CO. Delayed major vessel hemorrhage following tracheostomy. J Trauma 1973;13:235–7. 10.1097/00005373-197303000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peres LC, Mamede RC, de Mello Filho FV. Rupture of the aorta due to a malpositioned tracheal cannula in a 4-month-old baby. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1996;34(1-2):175–9. 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01252-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright CD. Management of tracheoinnominate artery fistula. Chest Surg Clin N Am 1996;6:865–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapural L, Sprung J, Gluncic I, et al. Tracheo-innominate artery fistula after tracheostomy. Anesth Analg 1999;88:777–80. 10.1213/00000539-199904000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelman JJ, Aro M, Weiss SM. Tracheo-innominate artery fistula. J Am Coll Surg 1994;179:626–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones JW, Reynolds M, Hewitt RL, et al. Tracheo-innominate artery erosion: Successful surgical management of a devastating complication. Ann Surg 1976;184:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper JD. Trachea-innominate artery fistula: successful management of 3 consecutive patients. Ann Thorac Surg 1977;24:439–47. 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)63438-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood DE, Mathisen DJ. Late complications of tracheotomy. Clin Chest Med 1991;12:597–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Utley JR, Singer MM, Roe BB, et al. Definitive management of innominate artery hemorrhage complicating tracheostomy. JAMA 1972;220:577–9. 10.1001/jama.1972.03200040089018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinley CE. A Technique of tracheostomy. Can Med Assoc J 1965;92:79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]