Abstract

Ticks cause approximately $17–19 billion economic losses to the livestock industry globally. Development of recombinant antitick vaccine is greatly hindered by insufficient knowledge and understanding of proteins expressed by ticks. Ticks secrete immunosuppressant proteins that modulate the host's immune system during blood feeding; these molecules could be a target for antivector vaccine development. Recombinant p36, a 36 kDa immunosuppressor from the saliva of female Dermacentor andersoni, suppresses T-lymphocytes proliferation in vitro. To identify potential unique structural and dynamic properties responsible for the immunosuppressive function of p36 proteins, this study utilized bioinformatic tool to characterize and model structure of D. andersoni p36 protein. Evaluation of p36 protein family as suitable vaccine antigens predicted a p36 homolog in Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, the tick vector of East Coast fever, with an antigenicity score of 0.7701 that compares well with that of Bm86 (0.7681), the protein antigen that constitute commercial tick vaccine Tickgard™. Ab initio modeling of the D. andersoni p36 protein yielded a 3D structure that predicted conserved antigenic region, which has potential of binding immunomodulating ligands including glycerol and lactose, found located within exposed loop, suggesting a likely role in immunosuppressive function of tick p36 proteins. Laboratory confirmation of these preliminary results is necessary in future studies.

1. Introduction

Ticks are considered among the most important vectors of livestock diseases worldwide as well as major vectors of pet diseases [1]. In tropical Africa, ticks and the tick-transmissible diseases constitute a major obstacle to livestock development [2]. Like elsewhere in the world, chemical acaricides have been the mainstay of tick control in this region; however, increasing resistance to this group of insecticides threatens livestock production systems, especially small-holding sectors that rely on rearing of exotic cattle breeds that are more susceptible to tick infestation and tick-borne diseases [TBDs] [3]. Integrated tick control incorporating reduced acaricide use, breeding cattle for tick resistance, rotational grazing, and use of vaccines presents a sustainable and long-term strategy to the control of ticks and TBDs in the tropics [4].

Numerous studies have shown the potential of immunological methods to control tick infestation by targeting critical tick physiological processes. Existing antitick vaccines work by eliciting humoral and cellular responses against tick cell membrane antigens [5, 6]. Vaccines capable of quelling both the arthropod vector and disease-causing pathogens are also under development [7]. Despite clear advantages of controlling ticks through vaccination, this strategy is presently hampered by antigenic sequence variations between geographically isolated tick populations and species causing vaccine resistance in some regions [8] and lack of efficacy in others [9]. These limitations necessitate search of alternative antigens for inclusion in the next-generation tick vaccines.

Proteins found in tick saliva play critical roles during blood meal acquisition [10]. The pharmacologically active components secreted in their saliva help ticks circumvent host defenses such as haemostatic and immune responses of the host, thereby enabling blood feeding in hematophagous arthropods [11]. One such class of biological compounds is immunosuppressant proteins, which modulate the host's immune system during tick's blood feeding [12], making them suitable target in the search of novel vaccines against arthropod-transmitted diseases [13]. Low molecular weight proteins 5–36 kDa from tick saliva proteins have been shown to inhibit T-lymphocytes proliferation in vitro [14]. Active immunization of mice with Salp15, a 15 kDa secreted salivary gland protein from I. scapularis, showed substantial protection (60%) from tick-borne Borrelia [15]. Tick subolesin (SUB), the ortholog of insect and vertebrate akirins (AKR), was discovered as a tick protective antigen in Ixodes scapularis [16]. Vaccines containing conserved SUB/AKR protective epitopes have been shown to protect against tick, mosquito, and sandfly infestations, thus suggesting the possibility of developing universal vaccines for the control of arthropod vector infestations [17].

Protein antigens conserved across vector species could be used in developing cross-protective vaccines against multiple arthropod vectors and their associated pathogens [17, 18]. Alarcon-Chaidez et al. [19] cloned and characterized a 36 kDa immunosuppressive protein p36 from the salivary glands of partially engorged, female D. andersoni, that suppressed Con-A induced in vitro proliferation of normal murine T-lymphocytes by more than 90% [20]. Genes related to D. andersoni-derived p36 gene, such as Ra-p36, Av-p36, Hl-p36, and Rhp36, have been reported in A. variegatum [21], R. appendiculatus [22], H. longicornis [23], and R. haemaphysaloides [24]. Most proteins are, however, not sufficiently protective on their own suggesting the need for a multiantigen/chimeric vaccine that incorporates critical tick and pathogen antigenic epitopes [16, 25] to elicit synergistic antipathogen and antitick immune responses. Computational characterization and 3D structure modeling of D. andersoni p36 protein undertaken by this study is an initial step in understanding molecular basis of immune recognition which is a challenge in vaccine development [26]. The p36 conserved antigenic region predicted by this study has binding residues for ligands like glycerol and lactose which are associated with an immunomodulatory role suggesting this site may have a role in suppression of select T-cell receptor induced signaling events of D. andersoni p36 and its related proteins.

2. Methods

2.1. Sequence Characterization of Tick p36 Proteins

All tick proteins deposited in National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) protein database were retrieved and deposited in a standalone MySQL based database (https://www.mysql.com). D. andersoni p36 protein was used as reference sequence in conducting homology searches, Blastp [27] and OrthoMCL [28, 29], of tick proteins in the database.

The identified tick p36-related proteins were subjected to MEME tool search (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) to predict conserved motifs characteristic of p36 proteins. Motif search tool (http://www.genome.jp/tools/motif) then searched for function of identified common motifs in the database of known motifs. Tick p36 protein sequences were then aligned by a multiple sequence alignment tool, Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo). Phylogenetic tree construction was by maximum likelihood method [30] and evolutionary distance computed using Poisson correction method [31]. Bootstrap resampling (1000 replicates) assessed robustness of the groupings.

2.2. Identification of Antigenic Determinants in the p36 Proteins

SignalP 4.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP), TMHMM (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM), and PredGPI (http://gpcr.biocomp.unibo.it/predgpi) servers were used to determine if tick p36 proteins are preferably secretory, transmembrane, or have a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) sites, respectively. Antigenic potentials of tick p36 proteins against reference Bm86, a known antitick vaccine antigen, were evaluated by vaxijen tool (http://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/vaxijen/VaxiJen/VaxiJen.html); the model selected was parasite whose standard threshold is 0.5000. The antigenic regions of D. andersoni p36 and other p36 proteins predicted with an antigenic score above 0.7000 were mapped by online tools that predict antigenic peptides (Immunomedicine) (http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/antigenic.pl) and SVMTrip [32]. Immunogenic segments/residues of the predicted antigenic region were identified by an online Epitopia tool (http://epitopia.tau.ac.il). Sprint-Pep tool (http://sparks-lab.org/server/SPRINT) was then used to predict protein-peptide binding sites while Coach tool (https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/COACH) predicted ligands likely to bind these sites found within the region predicted as a potential p36 protein conserved site.

2.3. Structural Modeling of D. andersoni p36 Protein

Physicochemical properties of D. andersoni p36 protein were analyzed by ExPASyProtParam (https://www.expasy.org) server while its secondary structure was characterized by online tool Spider2 (http://sparks-lab.org/yueyang/server/SPIDER2). The crystal or NMR structure of tick p36 protein is currently not available in the protein data bank (PDB) (https://www.rcsb.org/pdb/). The 3D structure of D. andersoni p36 protein was developed by QUARK ab initio modeling [33] that builds 3D structure from “Scratch,” based on physical principles rather than previously solved structures. 10 models, designated as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10, were generated and validated by analyzing Verify 3D scores [34] of Ramachandran plots for each model. Based on the scores, models 2 and 9 were selected as likely 3D structures of D. andersoni p36 protein because they scored 81.41% and 88.44%, respectively, meeting Verify 3D validation tool limit of 80% of the amino acids residues scoring >=0.2 in the 3D/1D profile.

The two selected models had their atomic structures refined by ModRefiner [35] after which their respective generated Ramachandran plots were validated by RAMPAGE (http://mordred.bioc.cam.ac.uk/~rapper/rampage.php) and ProQ (https://proq.bioinfo.se/ProQ/ProQ.html). The validation scores guided selection of model 2 as the best 3D structure of D. andersoni p36 protein. PDBsum (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/cgi-bin/pdbsum/GetPage.pl?pdbcode=index.html) was used to check location of predicted conserved antigenic region in the 3D structure of D. andersoni p36 protein.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of p36 Proteins from Ixodid Ticks

The study identified 32 homologs of D. andersoni p36 protein among 6 ixodid (hard) tick species (Table 1). These included p36 genes reported in earlier studies from R. appendiculatus, A. variegatum, H. longicornis, and Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides tick species as well as those found by this study in Amblyomma sculptum and Amblyomma aureolatum. Among these homologs, 4 co-orthologs which are potential orthologs of D. andersoni p36 protein were identified in R. appendiculatus species (Table 1). Occurrence of p36 protein across a range of tick species may be related to a biological function for this protein in tick feeding [36]. Several p36 immunosuppressant protein sequences were found in a single tick species suggesting functional and structural redundancy in which a tick expresses multiple similar proteins in minute quantities during feeding [37]. Such redundancy may render saliva proteins less immunogenic, as reported with cystatins [38].

Table 1.

Tick proteins related to D. andersoni p36 protein.

| Tick species | NCBI accession number |

Sequence similarity searches | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blastp homology search | OrthoMCL Search | |||||||

| Protein description% identityAlignmentE ValueBit score lengthaa | ||||||||

| D. andersoni | AAF03683.1 | p36∗ | 100 | 220 | 1.00E − 165 | 459 | Reference | Bergman et al., 2000 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP82151.1 | Da-p36 family member | 37.72 | 228 | 2.00E − 034 | 124 | Co-ortholog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP81510.1 | Da-p36 family member | 37.8 | 209 | 3.00E − 034 | 123 | Co-ortholog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP87204.1 | Da-p36 family member | 37.81 | 201 | 3.00E − 033 | 120 | Co-ortholog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP86350.1 | Da-p36 family member | 35.82 | 201 | 6.00E − 032 | 116 | Co-ortholog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| A. variegatum | BAD11807.1 | Da-p36 | 35.04 | 234 | 1.00E − 029 | 111 | In-paralog | Roller et al., 2004 |

| R. h. haemaphysaloides | ABB90890.1 | Rhh-ISP partial | 36.71 | 158 | 2.00E − 027 | 103 | In-paralog | Xiang et al., 2005 |

| A. sculptum | JAU03129.1 | Hypothetical protein partial | 35.06 | 231 | 1.00E − 026 | 103 | In-paralog | Eliane et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP81944.1 | Da-p36 family member | 32.3 | 226 | 2.00E − 024 | 97.4 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP88013.1 | Da-p36 family member partial | 31.58 | 228 | 2.00E − 024 | 97.4 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| A. sculptum | JAU02613.1 | Hypothetical protein partial | 27.65 | 217 | 2.00E − 016 | 74.3 | In-paralog | Eliane et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP85022.1 | Hypothetical protein | 25.11 | 231 | 7.00E − 016 | 72.8 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| A. sculptum | JAU02539.1 | partial Da-p36 family member | 32 | 175 | 2.00E − 015 | 70.9 | In-paralog | Eliane et al., 2016 |

| A. variegatum | DAA34595.1 | Da-p36 like | 27.95 | 229 | 3.00E − 015 | 70.9 | In-paralog | Ribeiro et al., 2011 |

| A. aureolatum | JAT98922.1 | Hypothetical protein partial | 31.65 | 218 | 4.00E − 015 | 70.5 | In-paralog | Martins et al., 2016 |

| A. aureolatum | JAT98921.1 | Hypothetical protein | 30.19 | 212 | 3.00E − 013 | 65.5 | In-paralog | Martins et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP85729.1 | Da-p36 family member | 26.24 | 221 | 4.00E − 013 | 65.1 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP85564.1 | Da-p36 family member | 25.47 | 212 | 2.00E − 012 | 63.5 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP82143.1 | Da-p36 family member | 23.31 | 236 | 2.00E − 011 | 60.1 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP86306.1 | Da-p36 family member | 25.74 | 237 | 3.00E − 011 | 60.1 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP81863.1 | Da-p36 family member | 27.14 | 210 | 6.00E − 011 | 59.3 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| A. variegatum | DAA34748.1 | Da-p36 like | 29.24 | 171 | 1.00E − 010 | 57.8 | In-paralog | Ribeiro et al., 2011 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP78061.1 | Da-p36 family member | 26.23 | 244 | 3.00E − 009 | 54.3 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP86680.1 | Da-p36 family member | 27.72 | 202 | 7.00E − 009 | 53.5 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP88255.1 | Da-p36 family member | 26.73 | 202 | 2.00E − 008 | 52 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP85730.1 | Da-p36 family member | 24.82 | 141 | 2.00E − 008 | 51.2 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| H. longicornis | BAG11660.1 | Isp-p36 | 31.78 | 107 | 1.00E − 007 | 50.1 | In-paralog | Nakajima et al., 2008 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP81735.1 | Da-p36 family member | 24.58 | 240 | 6.00E − 004 | 38.9 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP86324.1 | Da-p36 family member | 24.24 | 198 | 0.001 | 38.1 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| A. sculptum | JAU02519.1 | Hypothetical protein partial | 33.7 | 92 | 0.001 | 36.6 | In-paralog | Eliane et al., 2016 |

| A. variegatum | DAA34145.1 | ISP-p36 partial | 28.95 | 76 | 0.002 | 36.6 | In-paralog | Ribeiro et al., 2011 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP81446.1 | Da-p36 family member | 25.74 | 237 | 0.011 | 35 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

| R. appendiculatus | JAP86032.1 | Da-p36 family member | 25.18 | 139 | 0.019 | 34.3 | In-paralog | De castro et al., 2016 |

aaAmino acid; ∗reference p36 protein in D. andersoni.

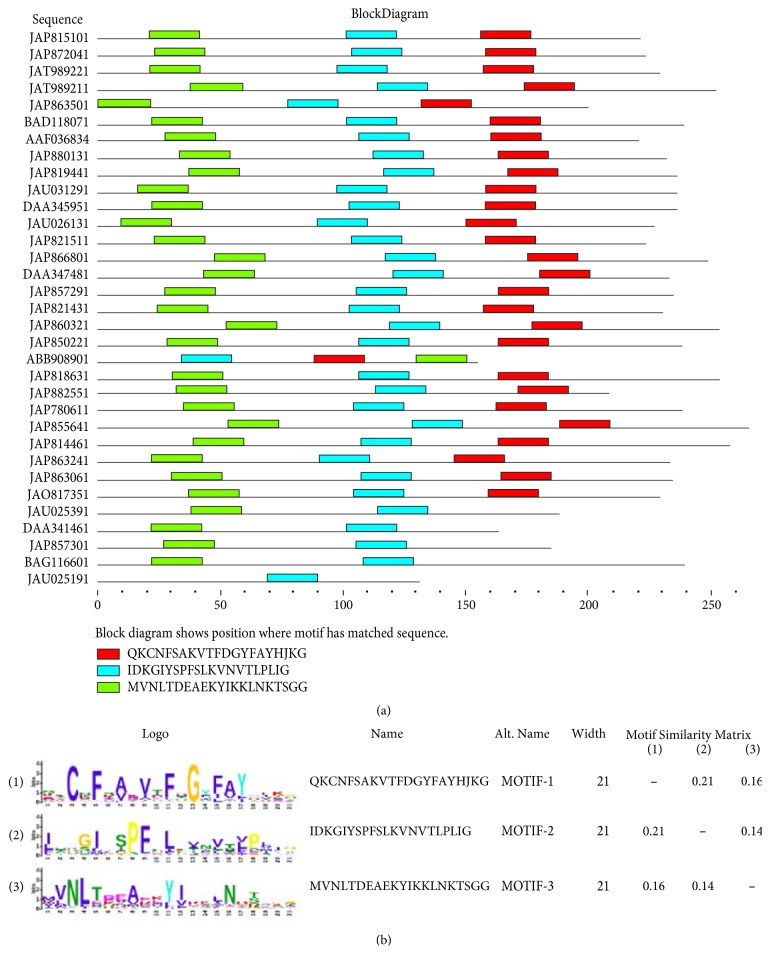

The tick p36 proteins have 3 potential common motifs designated as 1, 2, and 3 with motif 2 being the only one conserved among p36 proteins (Figure 1). Motif 2 is located between amino acid positions “107–127” in the reference D. andersoni p36 protein. This motif 2 may be associated with a functional domain, possibly a role in immunomodulatory activity of tick p36 proteins [39]. The 3 common motifs were not found in the motif database and could be representing an orphan protein family [40].

Figure 1.

(a) Occurrence of tandem motifs among p36 proteins. Motif 2 is conserved across all homologs; (b) motifs sequence logo analysis.

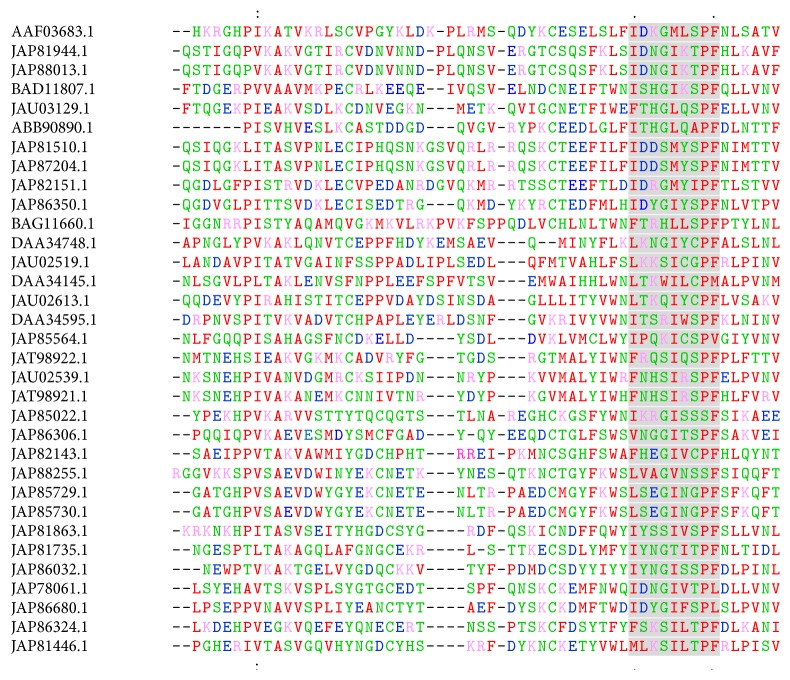

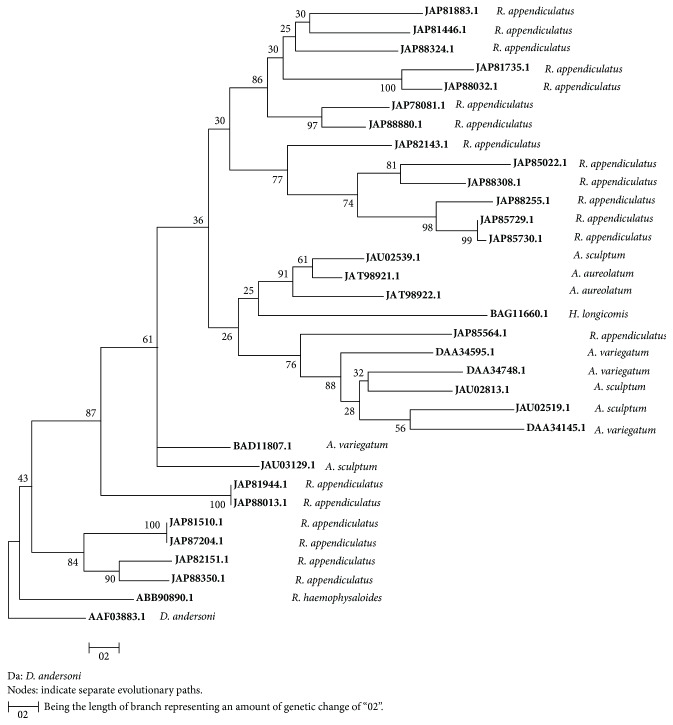

Alignment of tick p36 proteins revealed a conserved region occurring between amino acid positions “107–115” (“IDKGMLSPF”) in the reference D. andersoni p36 protein (Figure 2). This region that coincides with location of conserved motif 2 has polar amino acid residue serine (S) and charged residues lysine (K) and aspartate (D), which are associated with potential active sites [41]. Phylogenetic tree (Figure 3) showed that, among homologs with higher amino acid percentage similarity and E-scores, D. andersoni was closely related to homologs from R. haemophysaloides and R. appendiculatus as compared to homolog from A. variegatum indicating more recent ancestry between Dermacentor and Rhipicephalus than with Amblyomma genera as inferred by phylogeny [42].

Figure 2.

Multiple alignment of p36 homologous amino acid sequences showing likely conservation region. In the case of reference D. andersoni p36 protein, the conserved region “IDKGMLSPF” is located at positions “107–115.” (:) and (.): marks conservation between groups of strongly or weakly similar properties, respectively. Note. Amino acids colour according to physicochemical properties: red is for small hydrophobic, blue for acidic, magenta for basic, and green for hydroxyl/sulfhydryl/amine amino acid residues. Highlighted region shows conservation in tick p36 proteins.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relatedness between p36 proteins. Bootstrap resampling (1000 replicates) was employed to validate the robustness of the groupings yielded.

3.2. Identification and Characterization of Antigenic Regions in the p36 Proteins

Most tick p36 proteins were predicted as secretory with signal peptide cleavage site at position 21-22 (Supplementary Table S1 and Figure S1). Secretory proteins are favoured candidates for vaccine development as they are easily accessible microbial antigens to the immune system [43]. D. andersoni p36 protein and most p36 variants were predicted as antigenic with several homologs having antigenicity score above 0.7000 (Table 2, Supplementary Table S1), surpassing the vaxijen tool threshold of 0.5000. JAP81944.1, a homolog in R. appendiculatus had antigenicity score of 0.7701, comparably higher than that of Bm86 (0.7681), the constituent antigen of Tickgard and Gavac™ commercial tick vaccines. Whether this theoretically predicted immunogenicity can confer protection against tick infestation there is need to be evaluated empirically through an immunization/tick challenge set up.

Table 2.

Conserved motif 2 of tick p36 proteins mapped as a potential antigenic/binding site region.

| Tick species | NCBI accession number | Antigenic score | Conserved Motif 2 location | Antigenic region antigenic peptide tool/SVM Trip tool |

Mapped immunogenic segments of Motif 2 Epitopia tool |

Mapped Binding sites of Motif 2 Sprint pep tool |

Predicted ligands for Motif 2 Coach tool |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. andersoni | AAF03683.1 | 0.5880 | 107–127 | 95–128 | IDKGMLSPFNLSATVKFPLIP | IDKGMLSPFNLSATVKFPLIP | Lactose, Glycerol, NAG-(4-1)GAL, Sucrose |

|

| |||||||

| R. appendiculatus | JAP81944.1 | 0.7701 | 117–137 | 108–137 | IDNGIKTPFHLKAVFSFPITG | IDNGIKTPFHLKAVFSFPITG | - |

|

| |||||||

| R. appendiculatus | JAP88013.1 | 0.7379 | 113–133 | 104–133 | IDNGIKTPFHLKAVFSFPITG | IDNGIKTPFHLKAVFSFPITG | - |

|

| |||||||

| R. appendiculatus | JAP81510.1 | 0.7258 | 102–122 | 94–133 | IDDSMYSPFNIMTTVAFPLIG | IDDSMYSPFNIMTTVAFPLIG | B-Octylglucoside |

|

| |||||||

| R. appendiculatus | JAP86350.1 | 0.7072 | 78–98 | 74–110 | IDYGIYSPFNLVTPVQFPLMG | IDYGIYSPFNLVTPVQFPLMG | Alpha-D-Mannose, Alpha-D-Lactose, B-Octylglucoside |

Bold sections: tick p36 conserved region residues mapped as potentially antigenic/binding sites.

The potentially conserved motif 2 in p36 protein was predicted as a likely epitope-rich antigenic region with binding residues for glycerol and lactose ligands which are associated with an immunomodulatory role [44, 45]. To facilitate tick feeding a single tick saliva protein ligand may bind receptors on several immune cell types in the vertebrate host; alternatively, multiple tick saliva proteins may bind to a common receptor [37].

3.3. 3D Structure of D. andersoni p36 Protein

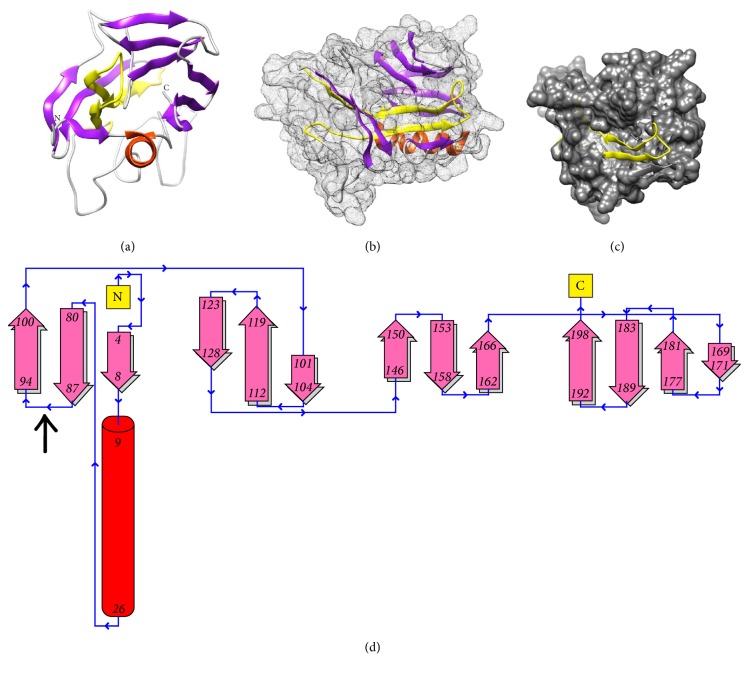

D. andersoni p36 protein has an instability index of 35.53 and GRAVY score of −0.324 classifying it as a stable, globular protein [46]. The protein's high aliphatic index of 86.41 is associated with increase in thermostability of globular protein [47]. The stable secondary structures alpha-helix (α) and beta-sheets (β) comprised approximately 55% of D. andersoni p36 protein amino acid sequence (Supplementary Figure S2). The predicted conserved immunogenic region “74–107” in processed secretory D. andersoni p36 protein had several segments within loop regions where epitopes are generally found [48]. The combination of α-helixes and β-structures through loops with specific geometric arrangements with respect to each is responsible in forming conserved structural motifs [49, 50].

Based on Verify 3D [34] scores of the 10 models designated as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 generated for D. andersoni p36 protein; models 2 and 9 were selected for further validation as they passed tool limit of 80% of the amino acids residues scoring >=0.2 in the 3D/1D profile (Supplementary Table S2). Comparison of validation scores of the selected models 2 and 9 (Table 3, Supplementary Figures S3 and S4) identified model 2 as the best 3D structure of D. andersoni p36 protein.

Table 3.

Validation of 3D structures for models 2 and 9 of D. andersoni p36 protein.

| Number | Validation tool | Parameter monitored | Limit | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | Model 9 | ||||

| (1) | ProQPsiPred | LGscore | LG score > 1.5 fairly good model LG score > 2.5 very good model LG score > 4 extremely good model |

LGscore 2.797 | LGscore 2.366 |

| MaxSub | MaxSub > 0.1 fairly good model MaxSub > 0.5 very good model MaxSub > 0.8 extremely good model |

MaxSub 0.208 | MaxSub 0.055 | ||

|

| |||||

| (2) | ProQJPred | LGscore | LG score > 1.5 fairly good model LG score > 2.5 very good model LG score > 4 extremely good model |

LGscore 2.914 | LGscore 2.231 |

| MaxSub | MaxSub > 0.1 fairly good model MaxSub > 0.5 very good model MaxSub > 0.8 extremely good model |

MaxSub 0.219 | MaxSub 0.046 | ||

|

| |||||

| (3) | Rampage tool | Favoured region residues Allowed region residues Outlier region residues |

156 (79.2%) 26 (13.2%) 15 (7.6%) |

152 (77.2%) 24 (12.2%) 21 (10.7%) |

|

The predicted 3D structure of D. andersoni p36 protein (Figures 4(a) and 4(b)) is a ball-like structure comprised of 1 alpha-helix and several antiparallel beta-strands. The region predicted as a likely conserved antigenic region “74⋯107” in D. andersoni p36 protein is not only located in between the alpha-helix and beta-strands but also occurs within the potentially groove region of the predicted 3D structure and further has its loop exposed on the protein surface (Figure 4(c)). Ligands bind in the largest cleft in over 83% of the proteins [51]; thus presence of the predicted conserved antigenic region within this potential groove may be associated with immunosuppressive function of D. andersoni p36 protein, as internal cavities in proteins are important structural elements that may produce functional motions such as ligand binding [52].

Figure 4.

(a, b) D. andersoni p36 protein predicted 3D structure ribbon and space field model; (c) predicted antigenic region “74–107,” in 3D structure of D. andersoni p36 protein. (d) Topology of D. andersoni p36 protein showing the likely predicted conserved exposed loop. Yellow: predicted conserved antigenic region “74–107”; red: α-helix secondary structure; purple: β-strands secondary structure. ↑: predicted exposed loop region “87–94” (“DKGMLSPF”) in D. andersoni p36, showing conservation in alignment of tick p36 proteins.

Potentially exposed loop region “87⋯94” (Figure 4(d)) in predicted 3D structure of D. andersoni p36 protein coincides with its likely conserved alignment region “107⋯115” after cleavage of signal peptide at amino acid position 21-22. This suggested loop region might be associated with binding site of D. andersoni p36 protein. The ligands predicted with potential to bind on this site include fatty acid glycerol and sugars like lactose. The hydroxyl group of polar amino acid residue serine (S), hydrophobic amino acid residue leucine (L), and charged amino acids lysine (K) and aspartic acid (D) found in this region could, respectively, have a role in binding of these ligands [53]. Immunomodulator ligands predicted with potential of binding at this site include fatty acid glycerol and sugars like lactose. There is need for future studies to evaluate whether immunomodulator ligands have a role in suppression of select T-cell receptor (TCR) induced signaling events in D. andersoni p36 protein mode of action [44, 45].

Collectively results from this in silico study provide further insight into potential characters of p36 protein, which is vital in exploiting the proteins as targets for developing improved next-generation cross-protective tick control approaches. In an effort to determine exact role of these proteins in tick feeding process, it is necessary for future laboratory and animal studies to confirm these preliminary predictive findings.

4. Conclusion

The p36 immunosuppressive proteins from ticks exhibit antigen traits worth evaluating in future experimental in vitro and in vivo trials. This includes potential conservation across several tick species and presence of a likely conserved antigenic region that may be bound by immunomodulator ligands such as glycerol and lactose. A further study is necessary on suitability of this potentially conserved region in development of a multi/chimeric antitick vaccine that incorporates critical antigenic regions. The predicted 3D model of D. andersoni p36 protein may be used as a template to model structures of other orphan proteins related to p36. This work is a step towards developing cross-protective next-generation antitick vaccines, as the results expand our knowledge of p36 tick saliva protein and lay ground for future studies to determine their exact role in tick feeding process, which is useful in designing blockade approaches targeting these proteins.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank CGIAR Fund Donors (http://www.cgiar.org/who-we-are/cgiar-fund/fund-donors-2) for supporting the study.

Disclosure

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sector.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: protein targeting pathway and antigenic potential of tick p36 proteins. Supplementary Table S2: Verify 3D validation scores of models generated for D. andersoni p36 protein. Supplementary Figure S1: D. andersoni p36 protein signal peptide cleavage site location. Supplementary Figure S2: Spider2 tool secondary structure characterization of D. andersoni p36 protein. Supplementary Figure S3: rampage tool assessment of Ramachandran plot for model 2 of D. andersoni p36 protein. Supplementary Figure S4: rampage tool assessment of Ramachandran plot for model 9 of D. andersoni p36 protein.

References

- 1.De La Fuente J., Estrada-Pena A., Venzal J. M., Kocan K. M., Sonenshine D. E. Overview: Ticks as vectors of pathogens that cause disease in humans and animals. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2008;13(18):6938–6946. doi: 10.2741/3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jongejan F., Uilenberg G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology. 2004;129(supplement 1):S3–S14. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004005967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbas R. Z., Zaman M. A., Colwell D. D., Gilleard J., Iqbal Z. Acaricide resistance in cattle ticks and approaches to its management: The state of play. Veterinary Parasitology. 2014;203(1-2):6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuente J., Kocan K. M., Blouin E. F. Tick vaccines and the transmission of tick-borne pathogens. Veterinary Research Communications. 2007;31(1):85–90. doi: 10.1007/s11259-007-0069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merino O., Alberdi P., Pérez De La Lastra J. M., de la Fuente J. Tick vaccines and the control of tick-borne pathogens. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00030.Article 30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De La Fuente J., Contreras M. Tick vaccines: Current status and future directions. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2015;14(10):1367–1376. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2015.1076339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oldiges D. P., Laughery J. M., Tagliari N. J., et al. Transfected Babesia bovis Expressing a Tick GST as a Live Vector Vaccine. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2016;10(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005152.e0005152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-García J. C., Montero C., Redondo M., et al. Control of ticks resistant to immunization with Bm86 in cattle vaccinated with the recombinant antigen Bm95 isolated from the cattle tick, Boophilus microplus. Vaccine. 2000;18(21):2275–2287. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odongo D., Kamau L., Skilton R., et al. Vaccination of cattle with TickGARD induces cross-reactive antibodies binding to conserved linear peptides of Bm86 homologues in Boophilus decoloratus. Vaccine. 2007;25(7):1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nuttall P. A., Trimnell A. R., Kazimirova M., Labuda M. Exposed and concealed antigens as vaccine targets for controlling ticks and tick-borne diseases. Parasite Immunology. 2006;28(4):155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontaine A., Pascual A., Diouf I., et al. Mosquito salivary gland protein preservation in the field for immunological and biochemical analysis. Parasites & Vectors. 2011;4(1, article no. 33) doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leboulle G., Crippa M., Decrem Y., et al. Characterization of a novel salivary immunosuppressive protein from Ixodes ricinus ticks. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(12):10083–10089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Titus R. G., Bishop J. V., Mejia J. S. The immunomodulatory factors of arthropod saliva and the potential for these factors to serve as vaccine targets to prevent pathogen transmission. Parasite Immunology. 2006;28(4):131–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anguita J., Ramamoorthi N., Hovius J. W. R., et al. Salp15, an Ixodes scapularis salivary protein, inhibits CD4+ T cell activation. Immunity. 2002;16(6):849–859. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai J., Wang P., Adusumilli S., et al. Antibodies against a tick protein, Salp15, protect mice from the Lyme disease agent. Cell Host & Microbe. 2009;6(5):482–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almazán C., Moreno-Cantú O., Moreno-Cid J. A., et al. Control of tick infestations in cattle vaccinated with bacterial membranes containing surface-exposed tick protective antigens. Vaccine. 2012;30(2):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno-Cid J. A., Pérez de la Lastra J. M., Villar M., et al. Control of multiple arthropod vector infestations with subolesin/akirin vaccines. Vaccine. 2013;31(8):1187–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parizi L. F., Githaka N. W., Logullo C., et al. The quest for a universal vaccine against ticks: Cross-immunity insights. The Veterinary Journal. 2012;194(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alarcon-Chaidez F. J., Müller-Doblies U. U., Wikel S. Characterization of a recombinant immunomodulatory protein from the salivary glands of Dermacentor andersoni. Parasite Immunology. 2003;25(2):69–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2003.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bergman D. K., Palmer M. J., Caimano M. J., Radolf J. D., Wikel S. K. Isolation and molecular cloning of a secreted immunosuppressant protein from Dermacentor andersoni salivary gland. Journal of Parasitology. 2000;86(3):516–525. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0516:IAMCOA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nene V., Lee D., Quackenbush J., et al. AvGI, an index of genes transcribed in the salivary glands of the ixodid tick Amblyomma variegatum. International Journal for Parasitology. 2002;32(12):1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nene V., Lee D., Kang'A S., et al. Genes transcribed in the salivary glands of female Rhipicephalus appendiculatus ticks infected with Theileria parva. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2004;34(10):1117–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konnai S., Nakajima C., Imamura S., et al. Suppression of cell proliferation and cytokine expression by HL-p36, a tick salivary gland-derived protein of Haemaphysalis longicornis. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;126(2):209–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang F., Lu X., Guo F., et al. The immunomodulatory protein RH36 is relating to blood-feeding success and oviposition in hard ticks. Veterinary Parasitology. 2017;240:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parizi L. F., Reck J., Oldiges D. P., et al. Multi-antigenic vaccine against the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus: A field evaluation. Vaccine. 2012;30(48):6912–6917. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulp D. W., Schief W. R. Advances in structure-based vaccine design. Current Opinion in Virology. 2013;3(3):322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer S., Brunk B. P., Chen F., et al. Using OrthoMCL to assign proteins to OrthoMCL-DB groups or to cluster proteomes into new ortholog groups. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 2011;(Chapter 6):19–10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0612s35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L., Stoeckert C. J., Jr., Roos D. S. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Research. 2003;13(9):2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whelan S., Goldman N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2001;18(5):691–699. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuckerkandl E., Pauling L. Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. E; 1965. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao B., Zhang L., Liang S., Zhang C. SVMTriP: a method to predict antigenic epitopes using support vector machine to integrate tri-peptide similarity and propensity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045152.e45152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu D., Zhang Y. Ab initio protein structure assembly using continuous structure fragments and optimized knowledge-based force field. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2012;80(7):1715–1735. doi: 10.1002/prot.24065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenberg D., Lüthy R., Bowie J. U. VERIFY3D: assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;277:396–404. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)77022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu D., Zhang Y. Improving the physical realism and structural accuracy of protein models by a two-step atomic-level energy minimization. Biophysical Journal. 2011;101(10):2525–2534. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de la Fuente J., Almazán C., Blas-Machado U., et al. The tick protective antigen, 4D8, is a conserved protein involved in modulation of tick blood ingestion and reproduction. Vaccine. 2006;24(19):4082–4095. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chmelař J., Kotál J., Kopecký J., Pedra J. H. F., Kotsyfakis M. All For One and One For All on the Tick-Host Battlefield. Trends in Parasitology. 2016;32(5):368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rangel C. K., Parizi L. F., Sabadin G. A., et al. Molecular and structural characterization of novel cystatins from the taiga tick Ixodes persulcatus. Ticks and Tick-borne Diseases. 2017;8(3):432–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sleator R. D., Walsh P. An overview of in silico protein function prediction. Archives of Microbiology. 2010;192(3):151–155. doi: 10.1007/s00203-010-0549-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tautz D., Domazet-Lošo T. The evolutionary origin of orphan genes. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12(10):692–702. doi: 10.1038/nrg3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reddy B. V. B., Li W. W., Shindyalov I. N., Bourne P. E. Proteins: Structure, Function and Genetics. 2001. Conserved key amino acid positions (CKAAPs) derived from the analysis of common substructures in proteins; pp. 148–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoogstraal H., Aeschlimann A. Tick-Host Specificity. Bull. La Société Entomol. Suisse. 1982;55:5–32. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bendtsen J. D., Wooldridge K. G. Bacterial secreted proteins: Secretory mechanisms and role in pathogenesis. Norfolk, UK: Caister Academy Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang M. S., Sandouk A., Houtman J. C. D. Glycerol Monolaurate (GML) inhibits human T cell signaling and function by disrupting lipid dynamics. Scientific Reports. 2016;6 doi: 10.1038/srep30225.30225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paasela M., Kolho K.-L., Vaarala O., Honkanen J. Lactose inhibits regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression of effector T-cell interferon-γ and IL-17 production. British Journal of Nutrition. 2014;112(11):1819–1825. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514001998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., et al. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. 2005. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server; pp. 571–607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikai A. Thermostability and Aliphatic Index of Globular Proteins. The Journal of Biochemistry. 1980:1895–1898. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dalkas G. A., Teheux F., Kwasigroch J. M., Rooman M. Cation-π, amino-π, π-π, and H-bond interactions stabilize antigen-antibody interfaces. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2014;82(9):1734–1746. doi: 10.1002/prot.24527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cowen L., Bradley P., Menke M., King J., Berger B. Predicting the beta-helix fold from protein sequence data. Journal of Computational Biology. 2002;9(2):261–276. doi: 10.1089/10665270252935458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conte M. R., Grüne T., Ghuman J., et al. Structure of tandem RNA recognition motifs from polypyrimidine tract binding protein reveals novel features of the RRM fold. EMBO Journal. 2000;19(12):3132–3141. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laskowski R. A., Luscombe N. M., Swindells M. B., Thornton J. M. Protein clefts in molecular recognition and function. Protein Science. 1996;5:2438–2452. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560051206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ogata K., Kanei-Ishii C., Sasaki M., et al. The cavity in the hydrophobic core of Myb DNA-binding domain is reserved for DNA recognition and trans-activation. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 1996;3(2):178–187. doi: 10.1038/nsb0296-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barnes M. R., Gray I. C. Bioinformatics for Geneticists. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: protein targeting pathway and antigenic potential of tick p36 proteins. Supplementary Table S2: Verify 3D validation scores of models generated for D. andersoni p36 protein. Supplementary Figure S1: D. andersoni p36 protein signal peptide cleavage site location. Supplementary Figure S2: Spider2 tool secondary structure characterization of D. andersoni p36 protein. Supplementary Figure S3: rampage tool assessment of Ramachandran plot for model 2 of D. andersoni p36 protein. Supplementary Figure S4: rampage tool assessment of Ramachandran plot for model 9 of D. andersoni p36 protein.