Abstract

Glycyl radical enzymes (GREs) are important biological catalysts in both strict and facultative anaerobes, playing key roles both in the human microbiota and in the environment. GREs contain a backbone glycyl radical that is post-translationally installed, enabling radical-based mechanisms. GREs function in several metabolic pathways including mixed acid fermentation, ribonucleotide reduction, and the anaerobic breakdown of the nutrient choline and the pollutant toluene. By generating a substrate-based radical species within the active site, GREs enable C-C, C-O, and C-N bond breaking and formation steps that are otherwise challenging for non-radical enzymes. Identification of previously unknown family members from genomic data and the determination of structures of well-characterized GREs have expanded the scope of GRE-catalyzed reactions as well as defined key features that enable radical catalysis. Here we review the structures and mechanisms of characterized GREs, classifying members into five categories. We consider the open questions about each of the five GRE classes and evaluate the tools available to interrogate uncharacterized GREs.

Keywords: glycyl radical enzymes, radical chemistry, anaerobic metabolism, pyruvate formate-lyase, class III ribonucleotide reductase, choline trimethylamine-lyase, benzylsuccinate synthase, radical decarboxylases

Introduction

Radical-based chemistry expands Nature’s catalytic repertoire, allowing enzymes to carry out otherwise inaccessible, chemically challenging transformations. Bacteria utilize a variety of radical sources in primary and secondary metabolism, including metal- or flavin-activated oxygen species, adenosylcobalamin, heme, and iron-sulfur cluster-activated S-adenosylmethionine. These cofactors initiate a reaction, typically by cleaving a C–H bond of a substrate, and the enzyme subsequently exerts intricate control over substrate- and product-based radical intermediates, guiding the radical-based chemistry toward the desired product. The product radical is reduced or oxidized to yield the product, sometimes regenerating the radical cofactor in the process. Occasionally, a protein-based radical rather than a substrate-based radical is generated by the cofactor. Protein-based radicals can be transient or stable and typically involve tyrosine, tryptophan, cysteine or glycine residues. Classic examples of stable protein-based radical species include the tyrosyl radical of class Ia ribonucleotide reductases and the glycyl radical of glycyl radical enzymes (GREs) such as class III ribonucleotide reductase (Sun et al., 1996) and pyruvate formate-lyase (PFL) (Wagner et al., 1992).

The glycyl radical enzyme (GRE) family is a group of homologous enzymes that employs a post-translationally installed glycyl radical cofactor in order to initiate radical-based chemistry (Shisler and Broderick, 2014). The reactions catalyzed by GREs are diverse (Fig. 1) and are involved in metabolic pathways including mixed acid fermentation following glycolysis (Knappe and Wagner, 1995), DNA synthesis (Sun et al., 1996), and anaerobic metabolism of toluene (Leuthner et al., 1998), choline (Craciun and Balskus, 2012), tyrosine/4-hydroxyphenylacetate (Yu et al., 2006), glycerol (O’Brien et al., 2004), and propane-1,2-diol (LaMattina et al., 2016). Although glycyl radicals have the benefit of being simple, protein-based radical storage cofactors, they are extremely oxygen-sensitive. Upon exposure to oxygen, the backbone of a GRE is cleaved at the site of the glycyl radical, rendering the protein enzymatically inactive (Wagner et al., 1992, Reddy et al., 1998, Zhang et al., 2001). In order to cope with changing redox environments, some facultative anaerobes express small proteins called autonomous glycyl radical cofactors that have high sequence similarity to the cleaved region of the GRE and are able to replace the damaged portion of the enzyme. These proteins may thus act as “spare-parts”, restoring enzymatic activity once anaerobic conditions return. This type of a repair system has only been shown to exist for PFL in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage T4 (Wagner et al., 2001), annotated as YfiD and Y06I respectively, but similar oxygen-damage repair proteins may exist for other GREs as well.

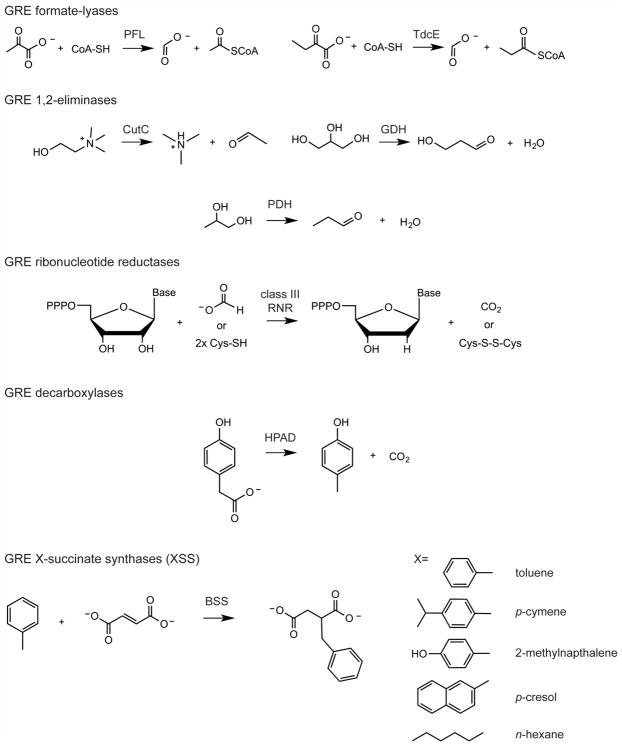

Figure 1. Classification of characterized GREs.

Five classes of GREs include: GRE formate-lyases (pyruvate formate-lyases, PFL, and ketobutyrate formate-lyases, TdcE); GRE 1,2-eliminases (choline trimethylamine-lyase, CutC, glycerol dehydratase, GDH, and propane-1,2-diol dehydratase, PDH); GRE ribonucleotide reductases (class III RNRs); and GRE decarboxylases (4-hydroxyphenylacetate decarboxylase, HPAD); and X-succinate synthases (XSSs where X= toluene in the case of benzylsuccinate synthase, BSS).

GREs are activated by members of the S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) radical superfamily, which utilize a reduced [4Fe-4S] cluster and AdoMet to generate a glycyl radical on the “Gly loop” of the GRE through direct, stereospecific hydrogen atom (H-atom) abstraction (Fig. 2) (Knappe et al., 1984, Cheek and Broderick, 2001, Sofia et al., 2001, Wang and Frey, 2007). In particular, the GRE activase reductively cleaves a molecule of AdoMet that is bound to an [4Fe-4S]1+ cluster, to generate a 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical species (5′-dAdo•), which in turn generates the glycyl radical on the GRE (Fig. 2C) (Wagner et al., 1992). During catalysis, the glycyl radical abstracts an H-atom from a neighboring Cys residue on the “Cys loop”. Although formation of a thiyl radical has never been directly detected in GREs, evidence of a thiyl radical intermediate is available for the closely related class II RNR from Lactobacillus leichmannii (Licht et al., 1996) and indirectly detected by H/D exchange in E. coli GRE class III RNR (Wei et al., 2014b). Despite the lack of direct evidence, the involvement of transient thiyl radical species in catalysis is widely accepted. Once formed, a transient thiyl radical is thought to initiate conversion of substrate to product through H-atom abstraction from the substrate (Fig. 2C) (Wagner et al., 1992). Following product formation, the thiyl radical is regenerated, which in turn regenerates the glycyl radical for storage until the next round of turnover.

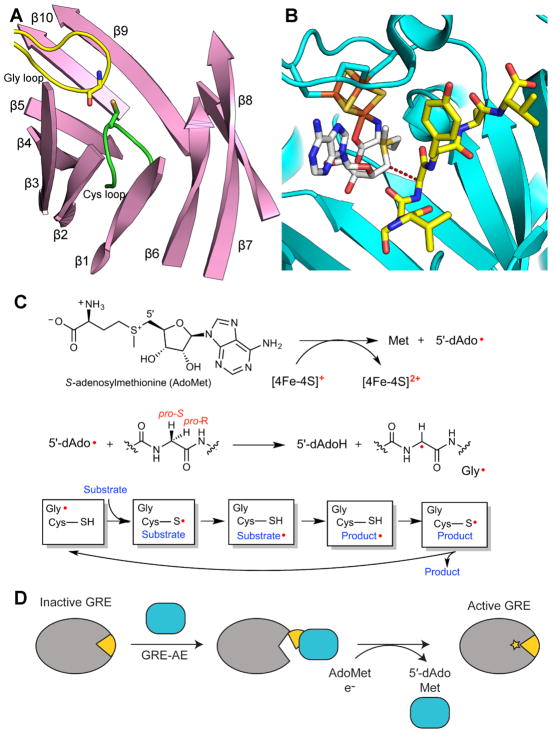

Figure 2. General overview of GRE activation and catalysis.

A. Ten β-strands surrounding the active site and two catalytic loops, the Gly (yellow) and Cys (green) loops, in the GRE PFL (PDB ID: 1H18). The α-helices and connecting loops are not shown. B. Active site of GRE activase PFL-AE (teal), showing the [4Fe-4S] cluster (orange and yellow), AdoMet (carbons in grey), and a 7-mer peptide substrate (yellow carbons) (PDB ID: 3CB8). Dashed line represents the 3.9-Å distance between the 5′ position of AdoMet and glycine residue of the 7-residue peptide, which has the same sequence as the Gly radical loop of PFL. C. A [4Fe-4S]1+ cluster reductively cleaves AdoMet to generate L-methionine and a 5′-dAdo radical species. The 5′-dAdo radical directly abstracts the pro-S hydrogen atom from the GRE glycine. Hydrogen atom transfer is thought to occur between the Gly radical and a neighboring Cys in the Cys loop to reversibly form a thiyl radical. This thiyl radical initiates catalysis. D. GRE-AE (teal) installs a Gly radical on the GRE in a reaction that is thought to require a conformational change of a region of the GRE known as the Gly radical domain (yellow). A color version of this figure is available online.

Similar to adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl) and AdoMet radical enzymes, GREs employ a barrel-like architecture to facilitate radical catalysis. AdoCbl and some AdoMet radical enzymes sequester the active site using a triose isomerase mutase (TIM) barrel fold, which has eight parallel β-strands arranged in a cylinder and surrounded by α-helices. In contrast, the GRE active site, comprised of the Gly and Cys loops, is found between two, five-stranded half barrels arranged antiparallel to each other with α-helices on the outside (Fig. 2A). In the active state, the Gly and Cys loops of GREs are juxtaposed for radical transfer back and forth; however, in order for the GRE activating enzyme (GRE-AE) to perform the initial H-atom abstraction, a conformational change of the barrel to an “open” state must occur in order to expose the buried glycine residue (Vey et al., 2008, Peng et al., 2010) (Fig. 2D). The region of the GRE that opens up to expose the glycine residue for activation has been coined the Gly radical domain (Vey et al., 2008).

Particularly for strict anaerobes, glycyl radicals are the ideal radical storage devices. Firstly, they are substantially less reactive than a typical organic radical; the adjacent electron-donating nitrogen and electron-accepting carbonyl produces a stabilizing effect by lowering the reduction potential of the glycyl radical, referred to as the captodative effect (Hioe et al., 2011). Furthermore, glycyl radicals are fairly “inexpensive” cofactors, requiring consumption of one AdoMet and one electron for each glycine activation; each activating enzyme is capable of acting on multiple GREs. The glycyl radical is regenerated every turnover, making it a suitable radical cofactor for central metabolic processes which require high turnover numbers and flux in order to power cellular energy conservation.

GREs were recognized early on as important enzymes in cellular energy maintenance and biosynthesis (Wagner et al., 1992, Sun et al., 1996), but recent discoveries suggest that GREs are more widespread and more diverse than originally thought. These enzymes are also emerging as drug targets. For example, gut microbes possessing the GRE choline trimethylamine-lyase (CutC) have been linked to trimethylaminuria, a genetic condition for which there is currently no treatment (Christodoulou, 2012). Furthermore some GREs play key environmental roles in anaerobic breakdown of recalcitrant pollutants, such as benzylsuccinate synthase (BSS), which enables bacteria to metabolize the common hydrocarbon pollutant toluene (Leuthner et al., 1998).

The GRE family was previously divided into three classes with one enzyme per class (Sawers, 1998): (1) pyruvate formate-lyases; (2) class III ribonucleotide reductases; and (3) benzylsuccinate synthases. At the time, this classification method was appropriate as available biochemical data suggested that GREs were limited to these three enzymatic roles. In a later review, it was proposed that the GREs should be divided into nine individual enzyme families: six of which were functionally characterized enzymes, and three of which were uncharacterized but widespread enzymes among anaerobes (Selmer et al., 2005). We now divide the family into five categories, grouping together GREs that perform similar biochemical reactions (Fig. 1), which we describe below. In addition, bioinformatic studies are identifying GREs at a rate much faster than they are being biochemically and structurally characterized. Thus, we will evaluate if it is possible to make predictions about function and mechanism based on sequence and homology models and how we can approach this task most effectively. Lastly, we will consider future directions of this field, and in particular, how researchers can apply knowledge of the GRE family to help solve key human health and environmental issues.

Biochemical and structural characterization of the glycyl radical enzyme family

GRE formate-lyases

Pyruvate formate-lyase (PFL) is the prototypical GRE in the formate-lyase class and one of the best-characterized GREs. It is a homodimer of 85 kDa monomers with a known structure (Becker et al., 1999, Leppanen et al., 1999, Becker and Kabsch, 2002) (Fig. 3A, B) and catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate and CoA to formate and acetyl-CoA. As the anaerobic counterpart to pyruvate dehydrogenase, PFL is central to anaerobic primary metabolism.

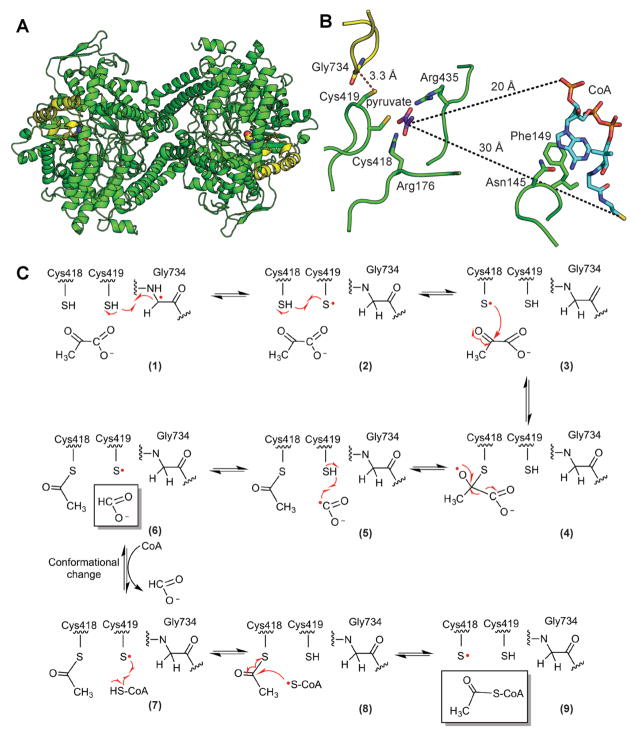

Figure 3. Structure and mechanism of PFL.

A. Ribbon drawing of the PFL homodimer with Gly radical as spheres and Gly radical domain in yellow (PDB ID: 2PFL) B. Structure of PFL with pyruvate and CoA (PDB ID: 1H16). Active site is set up for the first half reaction with Gly734 close to Cys419 and the Sγ of Cys418 close to C2 of pyruvate (2.6 Å). CoA is not in a catalytic position. It is found in the rare syn conformation, disengaged from the active site, with the CoA pyrophosphate group approximately 20 Å and the CoA thiyl group approximately 30 Å away from C2 of pyruvate. In order for the thiyl group of CoA to reach the active site to be acetylated, a dramatic conformational change must occur (Becker and Kabsch, 2002). C. Putative PFL mechanism (Becker and Kabsch, 2002). See text for discussion. A color version of this figure is available online.

An enzyme mechanism has been proposed (Fig. 3C) that is based on extensive biochemical and computational studies, primarily in Escherichia coli, and is supported by crystallographic snapshots of PFL (Becker et al., 1999, Leppanen et al., 1999, Becker and Kabsch, 2002). The first step in the mechanism is H-atom abstraction by the Gly radical (Gly734) to form the catalytically essential thiyl radical on Cys418 (Becker et al., 1999). Here the structure shows Gly734 adjacent to two conserved Cys residues (418 and 419), such that H-atom abstraction from the SH of Cys419 could be followed by H-atom abstraction from the SH of Cys418 to form a Cys418 thiyl radical (Becker and Kabsch, 2002) (Fig. 3B, C). The next step is a nucleophilic attack by the Cys418 thiyl radical on C2 of pyruvate, which would create a tetrahedral oxyradical intermediate (Fig. 3C, steps 3–4). This step is supported by a structure showing C2 of pyruvate perfectly positioned at 2.6 Å from Cys418 (Fig. 3B). The tetrahedral oxyradical intermediate is expected to collapse, forming a Cys418 acylated thioester and a formyl radical, which is then quenched to formate by Cys419 reforming a thiyl radical (Fig. 3C, steps 4–6). Although neither the formate binding site nor covalent adducts have yet been captured by crystallography, biochemical experiments support the current proposals (Plaga et al., 1988, Plaga et al., 2000). The final steps involve CoA attack on the Cys418 acylated thioester and product release (Fig. 3C, steps 7–9). Although a structure with CoA and pyruvate has been determined (Becker and Kabsch, 2002), CoA is not positioned for catalysis and is instead in a disengaged conformation, with the pantetheine chain extending away from the pyruvate that is bound in the active site (Fig. 3B). Consistent with data showing that CoA is not required for pyruvate cleavage (Knappe et al., 1974), this ternary structure is believed to mimic the positioning of pyruvate and CoA prior to the first half-reaction. In order for acetyl-CoA formation to occur, however, a structural change is required after the first half-reaction to transfer the acetyl moiety from Cys418 to the thiol group of CoA. Becker et al. proposed that CoA might shift from the syn to the anti conformation with the rotation of the ribose-pantetheine moiety around the N-glycosidic bond, positioning the thiol group approximately 5 Å away from the Cys418 and allowing for transfer of the acetyl group to form acetyl-CoA. Although this mechanistic proposal is reasonable based on model calculations (Becker and Kabsch, 2002), structural evidence for the proposed mechanism, particularly regarding the acetyl-enzyme intermediate and the CoA configuration change, remains elusive.

A second member of the GRE formate-lyases, TdcE, shares 82% sequence identity with PFL and can be activated by PFL-activating enzyme (PFL-AE). Functional complementation assays in E. coli show that TdcE can replace PFL activity during glucose fermentation (Sawers et al., 1998), but its main role is more likely to be in the anaerobic degradation of L-Thr, as TdcE is able to convert CoA and 2-ketobutyrate, the deamination product of L-Thr, into propionyl-CoA and formate (Hesslinger et al., 1998) (Fig. 2). Propionyl-CoA can be further processed to propionate, generating ATP.

GRE 1,2-eliminases

A subset of glycyl radical enzymes catalyzes 1,2-elimination reactions, analogous to the AdoCbl-dependent eliminases. Currently, this family consists of glycerol dehydratase (GDH) (O’Brien et al., 2004), propane-1,2-diol dehydratase (PDH) (LaMattina et al., 2016), and choline trimethylamine-lyase (CutC) (Craciun and Balskus, 2012).

GDH was first identified in strains of Clostridium butyricum that produce propane-1,3-diol in glycerol fermentation (Saint-Amans et al., 2001). GDH catalyzes the dehydration of glycerol to 3-hydroxylpropanal (Fig. 1), which is then reduced by a NADH-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase to generate propane-1,3-diol (Raynaud et al., 2003). GDH can also dehydrate propane-1,2-diol to propanal (and thus act as a PDH) (O’Brien et al., 2004), but it is unclear if this reaction is important in the bacteria that produce the enzyme.

PDH from the human gut bacterium Roseburia inulinivorans was first identified through genomic screening of genes involved in sugar degradation (Scott et al., 2006). This enzyme shares 48% sequence identity with GDH, but preferentially catalyzes the conversion of propane-1,2-diol into propanal (LaMattina et al., 2016) (Fig. 1). Recent analyses of the human gut microbiome suggest that PDH is both widespread and crucial in microbial anaerobic metabolism of sugars (Levin et al., 2017).

Another GRE eliminase, choline trimethylamine-lyase (CutC) cleaves choline to trimethylamine (TMA) and acetylaldehyde (Fig. 1) as the first step in anaerobic choline degradation (Craciun and Balskus, 2012). The cut operon (choline utilization) contains alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases, capable of acetaldehyde disproportionation to acetyl-CoA and ethanol. These genes in the cut operon are homologous to those used for AdoCbl-dependent ethanolamine and propanediol degradation. Currently, CutC enzymes from the bacteria Desulfovibrio alaskensis (Craciun et al., 2014, Bodea et al., 2016) and Klebsiella pneumonia (Kalnins et al., 2015) have been characterized.

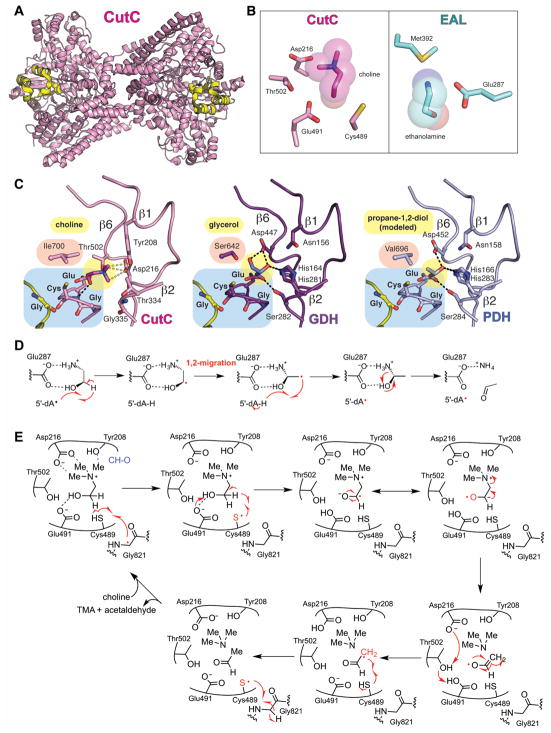

Structures of different GRE eliminases have been elucidated and show similarity to each other (O’Brien et al., 2004, Bodea et al., 2016, LaMattina et al., 2016). These enzymes adopt the canonical ten-stranded α/β barrel fold with the Gly and Cys loops in the center of the barrel (Fig. 4A). Within the Cys loop, the consensus motif GCXE appears to enable the elimination chemistry that is common to all three characterized enzymes. The presence of a Gly residue immediately before the catalytic Cys provides room for substrate to bind, and the Glu residue one residue downstream of Cys is the putative catalytic base that deprotonates the C1 alcohol (see below, Fig. 4E) (O’Brien et al., 2004, Bodea et al., 2016). Other residues important for catalysis are found on strands β1 and β6 (Fig. 4C). These strands provide substrate-specific contacts that influence binding and/or catalysis. Comparison of GDH and CutC, for example, reveals numerous hydrogen bond partners and a catalytic acid (His164) in GDH (O’Brien et al., 2004, Feliks and Ullmann, 2012), whereas CutC contains hydrogen bond acceptors (Tyr208, Asp216) that participate in CH–O interactions with the charged trimethylammonium moiety (Bodea et al., 2016). Although underappreciated, CH–O interactions are quite common in proteins and nucleic acid structures (Horowitz and Trievel, 2012, Adhikari and Scheiner, 2013, Horowitz et al., 2013), contributing as much as 1.2 kcal/mol to the binding energy and thus are similar to a hydrogen bond with OH and NH donors. A crucial difference between PDH and GDH is the presence of Val696 in PDH in place of Ser642 in GDH. The larger and more hydrophobic Val is thought to favor binding of propane-1,2-diol (modeled in Fig. 4C) in place of glycerol, which contains a hydroxyl group that would clash with this residue. A similar bulky residue (Ile700) occupies this space in CutC, where choline is oriented away from this face of the active site.

Figure 4. Structure and mechanism of GRE 1,2-eliminases.

A. Dimeric structure of CutC (pink, PDB ID: 5FAU) with Gly radical as spheres and Gly radical domain in yellow. B. Active sites of CutC with choline (pink) and AdoCbl-dependent ethanolamine ammonia-lyase with ethanolamine (EAL, teal) (PDB: 3ABO) showing that CutC has no residue that is equivalent to Glu287 or Met392 in EAL. C. Active sites of CutC, GDH, and PDH with hydrogen bonds shown as black dashed lines and CH-O interactions in CutC as gray dashed lines. Substrate positioning was determined by crystallography for CutC and GDH and is modeled for PDH. D. A proposed 1,2-migration mechanism for EAL (Wetmore et al., 2002). E. A proposed 1,2-elimination mechanism for CutC (Bodea et al., 2016). GDH and PDH are also likely to proceed through 1,2-elimination reactions. A color version of this figure is available online.

Mechanistic proposals have been put forth for both GDH and CutC (O’Brien et al., 2004, Craciun et al., 2014, Bodea et al., 2016). Similar to what has been proposed for AdoCbl-dependent enzymes diol dehydratase (DDH) (Smith et al., 2001) and ethanolamine ammonia lyase (EAL) (Wetmore et al., 2002), both GDH and CutC are thought to initiate catalysis by H-atom abstraction from the C1 of their respective substrates, in each case forming an α-hydroxy substrate radical species (Feliks and Ullmann, 2012, Craciun et al., 2014, Bodea et al., 2016) (Fig. 4D, E). In contrast to the use of a thiyl radical in GREs, DDH and EAL use a transient 5′-dAdo• radical species, formed by homolytic cleavage of the Co-C bond of AdoCbl that abstracts the C1-substrate hydrogen. Hydrogen bonding between residues of the active site and the α-hydroxy group of the respective substrates would be expected to lower the pKa of the C1 hydrogen, facilitating its abstraction by either radical cofactor. Despite the similarity of step-one, the mechanistic steps that follow are expected to be different for GREs compared to AdoCbl-dependent enzymes. AdoCbl-dependent enzymes are thought to proceed by a 1,2-migration of the departing heteroatom (Fig. 4D), a proposal that is supported by computational methods (Smith et al., 2001, Semialjac and Schwarz, 2002, Wetmore et al., 2002) and accompanying biochemical experiments (Retey et al., 1966a, Retey et al., 1966b, Valinsky and Abeles, 1975). In contrast, the GRE CutC is proposed to utilize a base-catalyzed 1,2-elimination mechanism (Craciun et al., 2014, Bodea et al., 2016) (Fig. 4E). There are active site differences between CutC and EAL that appear important in dictating the type of mechanism as described previously (Bodea et al., 2016). For example, EAL has an acidic residue, Glu287, which is positioned such that it could assist in a migration reaction and has Met392, which would appear to block elimination (Fig. 4B). CutC, on the other hand, has no equivalent residue to Glu287 of EAL (Fig. 4B) and modeling suggests that Thr502 would sterically block a migration reaction from proceeding (Bodea et al., 2016). In addition to variations in active site composition, the different redox potentials of the radical species involved in AdoCbl chemistry versus GRE chemistry are likely an important factor in determining mechanism. In particular, the product radical must re-abstract an H-atom from either 5′-dAdoH (in the case of an AdoCbl enzyme) or Cys-SH (in the case of a GRE), with the former being a more energetically demanding reaction. Thus, a mechanism that generates a highly reactive product radical species is more important for AdoCbl-dependent chemistry than it is for GRE chemistry, and the 1,2-migration reaction in EAL generates a very reactive product radical (re-abstraction of an H-atom from 5′-dAdoH calculated to be exothermic by 1.2 kcal/mol) (Fig. 4D) (Wetmore et al., 2002). With an easier H-atom re-abstraction in GREs (bond enthalpy is approximately 99.9 kcal/mol for 5′-dAdoH and 87 kcal/mol for Cys-SH), reaction mechanisms are not constrained to those that generate highly reactive product radicals. Indeed, computational studies of GDH found that a 1,2-migration mechanism is not necessary for H-atom re-abstraction from cysteine (Feliks and Ullmann, 2012).

GRE ribonucleotide reductases

Ribonucleotide reductases (RNRs) are essential enzymes in the de novo synthesis of deoxynucleotides from ribonucleotides, providing the building blocks for DNA replication and repair. Only the O2-sensitive class III RNRs employ a glycyl radical and are thus members of the GRE family, but all RNR classes share the “GRE fold”, i.e. the 10-stranded α/β barrel (Nordlund et al., 1990, Uhlin and Eklund, 1994, Sintchak et al., 2002). To the best of our knowledge class I (O2-dependent) and II (O2-independent) RNRs are the only non-GREs to use this fold. Despite the use of a common fold, sequence similarity analysis of the GRE superfamily shows that class III RNRs do not cluster close to other GREs (Levin et al., 2017), and here we assign class III RNRs as their own GRE subgroup (Fig. 1) even though elements of their mechanism are similar to GRE eliminases.

Despite being extremely oxygen sensitive, class III RNRs are found in both strict and facultative anaerobes. Several pathogens encode multiple RNRs of different classes and upregulate class III RNR, also known as NrdDs (“Nrd” for nucleotide reductase, “D” specifies class III RNR), to cope with oxygen limitation within biofilms (Cendra Mdel et al., 2012, Crespo et al., 2016). Knockouts of NrdDs in bacteria cause decreased virulence in animal infection models, suggesting that these enzymes enhance the ability of the bacteria to infect the host (Kirdis et al., 2007, Sjoberg and Torrents, 2011).

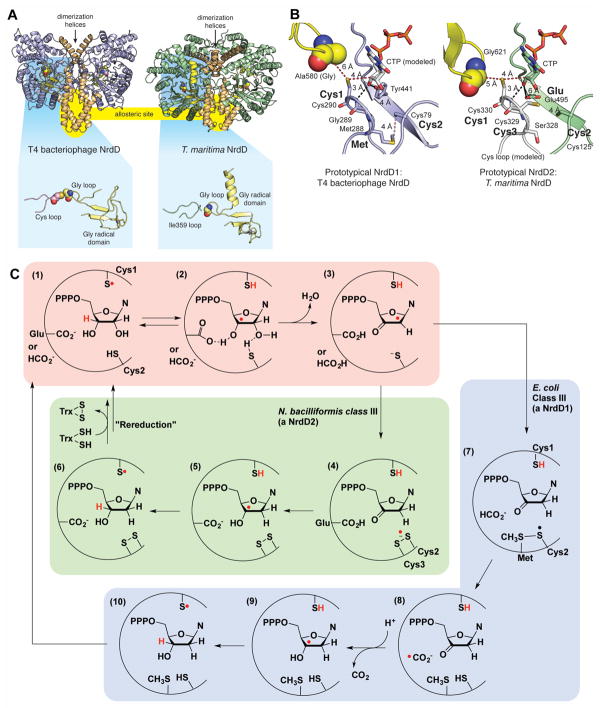

The class III RNRs from bacteriophage T4 (T4NrdD) and Thermotoga maritima (TmNrdD) have been structurally characterized (Larsson et al., 2001, Logan et al., 2003, Wei et al., 2014a) (Fig. 5A). Like many other GREs, RNRs are dimeric, but the dimer interfaces are distinct (Fig. 3–7A). In RNRs, these interfaces are functionally important; they are allosteric regulatory sites (Andersson et al., 2000, Larsson et al., 2001). The Gly radical domain of class RNRs are also unusual in that they have a structural zinc-binding site (Fig. 5A), the full function of which is not known. Within the active site of T4NrdD, the Cys loop and Gly loop are present as in other GREs; however, degradation or misfolding of the Cys loop in the TmNrdD structure results in loss of this loop from the active site and replacement by a loop bearing Ile359 in place of the Cys loop cysteine (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Structure and mechanism(s) of class III RNRs (NrdDs).

A. Two NrdD structures with helices comprising the dimeric interface shown in brown. Location of an allosteric site at the dimeric interface is highlighted in yellow. Zoomed out views of the active sites are shown highlighted against a blue background. Both structures contain a zinc (grey sphere) site in the Gly radical domain (shown in yellow), but in the T. maritima structure (PDB 4U3E), the Cys loop (pink) is missing, replaced by a different loop (Ile359 loop in green). B. Active site models that are based on the structures of a formate-utilizing NrdD1 (T4 phage NrdD) and a disulfide-utilizing NrdD2 (T. maritima NrdD). Key residues for catalysis are marked in bold. Distances are given in ångstroms. CTP in the T4NrdD structure is modeled from TmNrdD (PDB ID 4COJ). The Cys loop in TmNrdD was generated manually in PyMol through in silico mutagenesis and torsion angle adjustment to relieve clashes. C. Mechanistic proposals for NrdD1 and NrdD2 enzymes (Wei et al., 2014a, Wei et al., 2014b). See text for description. A color version of this figure is available online.

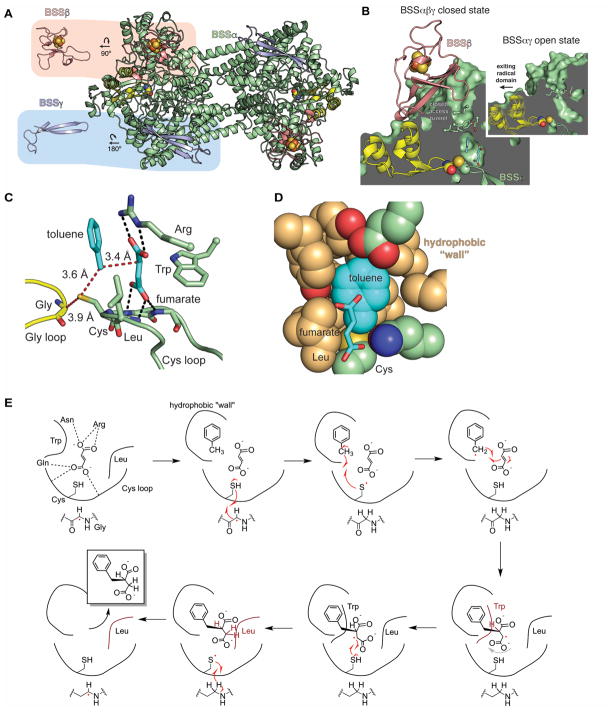

Figure 7. Structure and mechanism of BSS.

A. The BSS heterohexamer is formed by a central BSSα dimer (green with Gly radical domain in yellow) and associated BSSβ (salmon) and BSSγ (light blue) monomers. BSSβ contains a [4Fe-4S] cluster (spheres) whereas BSSγ is partially disordered in the crystal structure and is missing its cluster. B. BSSβ (salmon) contacts the Gly radical domain (yellow) and juts into the putative substrate access channel (green). In the structure without BSSβ (inset), the access channel is more open and the Gly radical domain is shifted away from the Cys loop (closed state shown as faded model, open state as solid). C. The active site of BSS positions the substrates toluene and fumarate such that the expected radical transfer distances (red dashes) are minimized. Hydrogen bonds (black dashes) and van der Waals contacts secure fumarate into place above the Cys loop. D. Van der Waals interactions from the “hydrophobic wall” secure toluene positioning. E. Proposed structure-based mechanism for BSS (Funk et al., 2015). A color version of this figure is available online.

Until recently it was thought that all class III RNRs used formate as the reductant for ribonucleotide reduction and utilized a conserved set of active site residues, but recent phylogenetic analyses on class III RNRs (Wei et al., 2014a, Aurelius et al., 2015) and a metabolic pathway analysis (Wei et al., 2015) have suggested that this is not the case. Currently, it appears that there are at least three subclasses of NrdDs, which can be distinguished by the presence or absence of 3–4 catalytic residues and the requirement for formate as the reductant. T4NrdD and TmNrdD are prototypes for two of these subclasses, NrdD1 and NrdD2, and thus contain a different set of active site residues (labeled as Cys1, Cys2, and Met in T4NrdD vs. Cys1, Cys2, Cys3, and Glu in TmNrdD in Fig. 5B). The catalytic components shared by both are two cysteine residues, Cys1 and Cys2, which participate in H-atom transfer and nucleotide reduction, respectively. Decades of work on class I and class II RNRs, which also contain these two cysteine residues, have produced a unified model for the enzymatic mechanisms of these RNRs (Stubbe and van der Donk, 1995). Recent mechanistic investigations have shown that NrdDs share a related mechanism (Wei et al., 2014a, Wei et al., 2014b), which consists of two distinct stages. Stage 1 in all class I, II, and III RNRs studied so far is dehydration of the ribonucleotide 2′ carbon. This reaction requires the abstraction of the 3′ hydrogen by the Cys1 thiyl radical to form the 3′ substrate radical (Fig. 5C, steps 1–2) and a general base catalyst to facilitate water loss by deprotonating the 3′ hydroxyl group (Fig. 5C, steps 2–3). The general base is thought to be formate in NrdD1 (Mulliez et al., 1995) or an active site glutamate in NrdD2 (Wei et al., 2014a). Overall, these steps are similar to the dehydration proposed for the GRE eliminases.

The second stage is reduction of the resulting 2′-deoxy-3′-keto-nucleotide to generate a 3′-deoxynucleotide radical (steps 4–5, 8–9) that re-abstracts the thiol hydrogen, resulting in deoxynucleotide formation and return of the radical to the storage cofactor. Experiments with the NrdDs from E. coli (EcNrdD) (Wei et al., 2014b) and Neisseria bacilliformis (NbNrdD) (Wei et al., 2014a) have revealed that stage 2 involves at least two mechanisms and two kinds of reducing agents.

Oxidation of formate to CO2 serves as the source of reducing equivalents in E. coli NrdD (Mulliez et al., 1995), which is a member of the NrdD1 subclass and a very close homolog of T4NrdD. Two key residues are thought to be involved in formate oxidation (Fig. 5B): Cys2 and Met. Following dehydration at the 2′ position, Cys2 is oxidized by H-atom abstraction and forms a stable thiosulfuranyl radical with the adjacent Met (Fig. 5C, steps 3–7) (Wei et al., 2014b). H-atom abstraction from formate restores Cys2 and Met and provides the putative reductant for the ketonucleotide, a formyl radical (Fig. 5C, steps 7–9)—a species also proposed in the PFL mechanism (Becker and Kabsch, 2002). Re-abstraction of the H-atom from Cys1 completes the nucleotide reduction (Fig. 5C, steps 9–10).

NrdD2 enzymes, exemplified by the N. bacilliformis class III RNR, do not require formate (Wei et al., 2014a). Instead, N. bacillioformis RNR obtains its reducing equivalents from a thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system in analogy with class I and II RNRs (Wei et al., 2014a). Using knowledge of class I and II enzymes, Wei and coworkers have proposed that a pair of Cys residues, Cys2 and Cys3 (Fig. 5B), are reduced in a thioredoxin-dependent reaction prior to turnover and act as the immediate source of reducing equivalents during turnover (Wei et al., 2014a). Following elimination of water, Cys2 and Cys3 are oxidized by the 2′ radical, creating a disulfide anion radical (Fig. 5C, steps 3–4). This species is expected to reduce the ketonucleotide as Glu reprotonates the 2′ hydroxyl group (Wei et al., 2014a) (Fig. 5C, steps 4–5). H-atom abstraction produces the deoxyribonucleotide and leaves behind a disulfide that must be re-reduced prior to another round of turnover (Fig. 5C, steps 5–6).

A third subclass (NrdD3) was recently investigated (Wei et al., 2015): MbNrdD from Methanosarcina barkeri lacks the conserved Glu residue thought to be the catalytic acid/base in NrdD2 enzymes. MbNrdD nonetheless contains Cys2 and Cys3 and does not oxidize formate, like NrdD2 enzymes. Instead of thioredoxin, it uses the glutaredoxin-like protein NrdH to acquire electrons from reduced ferredoxin through a ferredoxin:disulfide reductase. No structure of a member of this subclass is available.

It is interesting to consider the origins of these different subclasses of NrdDs. One possibility is that the evolution of NrdD subclasses was driven by the availability of formate as a reductant (Wei et al., 2014a, Wei et al., 2015). Formate-dependent NrdD1s are found in organisms that generate formate as a byproduct of anaerobic metabolism by PFL in fermenting bacteria or by electron-bifurcating heterodisulfide reductase in some methanogens. NrdD2s and NrdD3s are primarily found in bacteria and archaea that lack a source of formate in their primary metabolism. More nuanced divisions into the source of reducing equivalents for disulfide-utilizing NrdDs may be discernable with additional experiments.

GRE decarboxylases

GRE decarboxylases include the structurally and biochemically characterized 4-hydroxyphenylacetate decarboxylase (HPAD) (Selmer and Andrei, 2001) and a recently identified putative phenylacetate decarboxylase (PAD) from an anaerobic, sewage-derived enrichment culture (Zargar et al., 2016). Although PAD does show some 4-hydroxyphenylacetate decarboxylation activity, it also appears to catalyze the conversion of phenylacetate to toluene, and may represent a second member of this GRE subfamily.

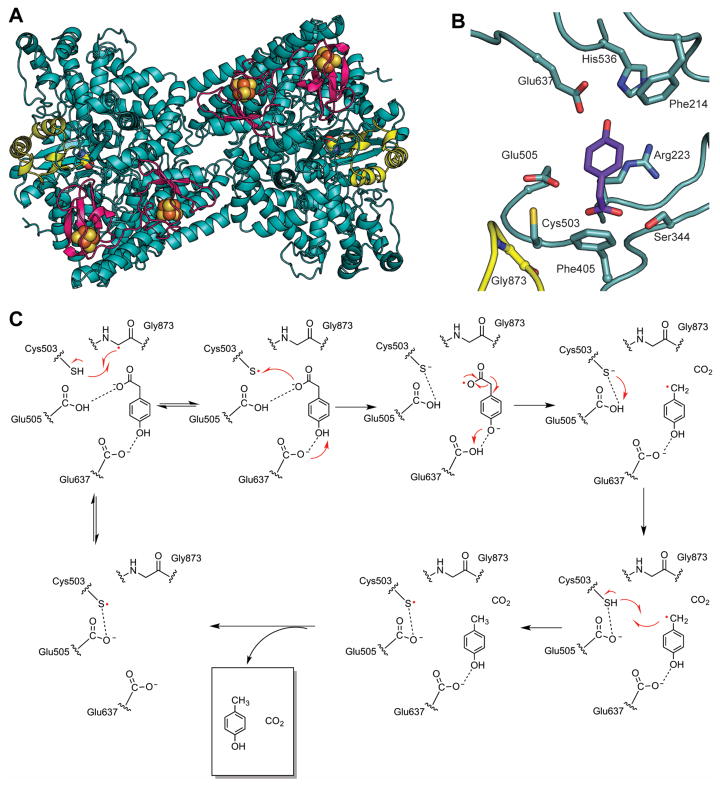

HPAD, which has been the subject of a recent review (Selvaraj et al., 2016), cleaves the tyrosine-derived metabolite 4-hydroxyphenylacetate to p-cresol and carbon dioxide (D’Ari and Barker, 1985, Selmer and Andrei, 2001). p-cresol is thought to promote virulence of Clostridium difficile and related pathogens (Dawson et al., 2008). HPAD from Clostridium difficile (Selmer and Andrei, 2001, Blaser, 2006), Clostridium scatologenes (Yu, 2006, Martins et al., 2011), and Tannerella forsythensis (Yu, 2006) have been characterized. HPAD is a functional heterotetramer (βγ)4 composed of 100 kDa catalytic subunits (β) which harbor the Gly and Cys loops, and small 9.5 kDa subuits (γ) that bind two [4Fe-4S] clusters located approximately 40 Å away from the active site (Martins et al., 2011) (Fig. 6A). The γ-subunits are structurally homologous to high potential iron-sulfur proteins (HiPIP) but their function(s) are not fully established (Martins et al., 2011). This structural architecture of HPAD introduces a new subclass of [4Fe-4S] cluster-containing GREs that also includes BSS.

Figure 6. Structure and mechanism of HPAD.

A. HPAD heterotetramer displaying large catalytic β-subunits (teal, with glycyl radical domain in yellow) and small γ-subunits (magenta) each binding two [4Fe-4S] clusters (PDB code: 2YAJ). B. 4-Hydroxyphenylacetate (4HPA, purple) bound in the active site of HPAD. Active site residues are shown as sticks and labeled. Notably, 4HPA binds with the carboxylate group proximal to the catalytic Cys503, suggesting radical transfer to the carboxylate group. C. Proposed decarboxylation mechanism for decarboxylation of 4HPA (Martins et al., 2011). A color version of this figure is available online.

Originally, it was postulated that the difficult decarboxylation of 4-hydroxyphenylacetate likely proceeded through an “Umpolung”, or polarity inversion mechanism, with catalysis initiated by abstraction of an H-atom from the hydroxyl group of the substrate by the thiyl radical (Selmer and Andrei, 2001, Buckel and Golding, 2006). However, the substrate-bound structure of HPAD revealed an unexpected twist (Martins et al., 2011); the carboxylate group was positioned near the catalytic Cys residue instead of the hydroxyl group, which would have been necessary for the previously proposed mechanism (Fig. 6B). This structure instead suggested the reaction would proceed through a biologically unprecedented Kolbe decarboxylation mechanism (Fig. 6C). Kolbe decarboxylation mechanisms are defined by the one-electron oxidation of carboxylate ions, typically producing alkyl radicals after decarboxylation (Kolbe, 1849, Vijh and Conway, 1967). In this case, the proximity of the carboxylate moiety of substrate to Cys503 suggests that the Cys503 thiyl radical could oxidize the carboxylate group during catalysis, leading to decarboxylation (Martins et al., 2011, Feliks et al., 2013). Here, an interesting use of the largely conserved Cys loop Glu is proposed; it is postulated to act as a catalytic acid and protonate Cys503 after oxidation of the substrate and reduction of the thiyl radical (Martins et al., 2011) (Fig. 6C). Following decarboxylation, the product radical would then be able to abstract the H-atom from the thiol of Cys503 to regenerate the thiyl radical. As the putative GRE PAD appears to perform a decarboxylation on both 4-hydroxyphenylacetate and phenylacetate, a molecule lacking the hydroxyl group required for a Kolbe decarboxylation mechanism, this enzyme is likely to proceed through a novel mechanism, if it indeed also uses a glycyl radical cofactor for catalysis (Zargar et al., 2016). Additional studies of this subclass should help to clarify some of the outstanding questions.

X-succinate synthases

Hydrocarbon pollutants from both natural and human sources are naturally degraded by bacteria as a source of carbon and energy. The X-succinate synthases (XSSs) perform a remarkable C-C bond forming reaction on inert hydrocarbon substrates. This family includes benzylsuccinate synthase (BSS) and other enzymes that are proposed to act on both aryl and alkyl substrates, termed arylsuccinate synthases (aryl-SS) and alkylsuccinate synthases (alkyl-SS), respectively. Collectively, these enzymes have been referred to as XSS (where X is the resulting hydrocarbon adduct) (Fig. 1). XSSs have been documented in nitrate, sulfate, and metal ion-reducing bacteria living in environments affected by hydrocarbon pollution (Acosta-Gonzalez et al., 2013) and in syntrophic communities of methanogenic archaea and sulfate-reducing bacteria (Beller and Edwards, 2000). Crucially, XSS enzymes are active under anoxic conditions, and are an important contributor to bioremediation of habitats such as the deep ocean and underground aquifers (Beller et al., 2002).

Conversion of toluene into R-benzylsuccinate is catalyzed by BSS with fumarate as a co-substrate (Biegert et al., 1996). The BSS-encoding operon of Thauera aromatica is surprisingly large, containing at least six genes. Like other GRE gene clusters, these include genes encoding an AdoMet radical activating enzyme and a large protein with homology to GREs that is the catalytic subunit of BSS. Two small genes encode 7 and 9 kDa proteins that form a complex with the catalytic subunit (Leuthner et al., 1998) and are essential for viable growth of T. aromatica on toluene (Coschigano, 2002). The operon contains at least two more genes of unknown function, which have been shown to be important for BSS function in vivo (Hermuth et al., 2002, Kube et al., 2004, Bhandare et al., 2006). Although BSS activity has been characterized in crude cell extracts (Leuthner et al., 1998, Beller and Spormann, 1999, Qiao and Marsh, 2005, Li and Marsh, 2006a, Li and Marsh, 2006b) and the non-activated protein can be purified from E. coli (Li et al., 2009), purification of the activase has so far been intractable, thus limiting the scope of biochemical studies.

Biophysical and structural data indicate that heterologously produced BSS forms a stable (αβγ)2 heterohexamer (Fig. 7A) (Leuthner et al., 1998, Beller and Spormann, 1999, Li et al., 2009, Funk et al., 2014). The catalytic BSSα subunit contains the ten-stranded α/β barrel fold that is found in all GREs, whereas BSSβ and BSSγ are small, [4Fe-4S] cluster-containing proteins that are similar in structure to the small subunits of HPAD (Martins et al., 2011, Funk et al., 2014). BSSγ, which is disordered in the crystal structure and missing its [4Fe-4S] cluster, appears to be important for the solubility of BSSα (Funk et al., 2014). In contrast, BSSβ, which is observed with an intact [4Fe-4S] cluster, binds near the glycyl radical domain, suggesting a possible role in the glycyl radical formation (Fig. 7B) (Funk et al., 2014). In fact, a comparison of crystal structures with and without BSSβ shows that the absence of BSSβ alters the positioning of the glycyl radical domain toward the exterior of the enzyme (Fig. 7B) (Funk et al., 2014). Additionally, BSSβ contacts the region of BSSα at the top of the putative substrate channel where its presence could help secure toluene in the active site cavity, i.e. plug the channel preventing toluene escape (Fig. 7B) (Funk et al., 2015).

Structures of BSS show fumarate and toluene bound within the active site cavity, adopting optimal orientations for radical-mediated C-C bond formation (Funk et al., 2015) (Fig. 7C). Fumarate is sandwiched between a Leu and a Trp residue within the Cys loop and is held in place by hydrogen bonds with the Cys loop backbone and an Arg residue. Toluene is constrained in the active site, with fumarate packed against one face of the ring, and hydrophobic residues packing against the other face and against the sides of toluene, forming a “hydrophobic wall” (Fig. 7D). Thus, despite having no functional handles, toluene is held in the correct orientation within the active site. These structural data, in accordance with prior biochemical and computational experiments (Qiao and Marsh, 2005, Li and Marsh, 2006b, Seyhan et al., 2016), inspired the current mechanistic proposal for R-benzylsuccinate synthesis (Funk et al., 2015) (Fig. 7E).

Binding of both substrates must be required to initiate H-atom abstraction from the toluene methyl group (Fig. 7E). The substrates are prearranged in the active site to allow for immediate formation of the product-like benzylsuccinyl radical (Funk et al., 2015). A slight rearrangement of this radical is necessary for H-atom abstraction from the active site Cys to generate product and re-generate the thiyl radical. The Leu and Trp residues that surround fumarate may play a role in guiding the product radical toward the Cys residue through steric interactions (Fig. 7E). Exit of the product may also be promoted by the change in geometry within the active site—so far no product bound structure has been obtained. Quantum mechanical modeling based on the structure supports this proposed mechanism and suggests that H-atom abstraction is the rate-limiting step (Szaleniec and Heider, 2016).

Although most biochemical and all structural investigation have been pursued with BSS, several homologs with known aryl and alkyl hydrocarbon substrates have been identified, including 4-isopropylbenzyl-SS (IBSS) (Harms et al., 1999, Strijkstra et al., 2014), hydroxybenzyl-SS (HBSS) (Müller et al., 2001, Wohlbrand et al., 2013), naphthyl-2-methyl-SS (NMSS) (Selesi et al., 2010), and 1-methylalkyl-SS (MASS) (Rabus et al., 2001, Callaghan et al., 2008, Grundmann et al., 2008) (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analysis and computational modeling (Funk et al., 2015, Heider et al., 2016) supports the notion of coevolution of active site residues with changing substrate specificity. In general, residues in the Cys loop that play a role in fumarate binding are conserved within the XSS family but not in other GREs. In contrast, residues predicted to make up the “hydrophobic wall” in other XSSs show little sequence conservation. Taken together, these findings suggest that the core chemistry performed by XSS enzymes will be conserved, but that the active site periphery has been remodeled to accommodate different substrates. Much work remains to be done, however, both in natural habitats and in the lab to characterize the substrate scope and distribution of XSSs. Of particular interest is how MASS enzymes bind and perform H-atom abstraction on alkanes.

Making and testing predictions about uncharacterized GREs

In the next four sections, we consider the approaches that are being used to make predictions about uncharacterized GREs and the tools that are available to interrogate newly discovered GREs. A recent phylogenetic analysis shows that there is a considerable amount of uncharacterized sequence space in the GRE superfamily (Levin et al., 2017). Of the 6343 non-RNR sequences in the InterPro genome database (IPR004184) about half are PFLs or related formate-lyases, leaving considerable sequence space for the remaining GRE subclasses and for new chemistry and new GREs to be discovered.

Predictions based on sequence similarity

With so many uncharacterized GREs, it is unfortunate that predicting chemistry based on sequence similarity in this enzyme family remains so challenging. For example, the two eliminases CutC and GDH are 37% identical despite working on entirely different substrates. Additionally, the X-succinate synthase BSS and the eliminase GDH are 29% identical despite catalyzing different reactions on different substrates. These relatively high similarities, in part, stem from the fact that all GREs share the core 10-stranded α/β-barrel architecture, which shields the radical from exposure to solvent and binds substrate close to the catalytic cysteine; thus some of the conservation may afford retention of these important structural features (Lehtio and Goldman, 2004). Secondly, all GRE reactions have a common set of activation and initiation steps, which may restrain evolution of residues in regions of the protein outside of the active site.

Making predictions about chemistry from sequence motifs is also challenging. As discussed in the previous sections, there are sequence motifs within the Cys loop that appear associated with particular subclasses of GREs. For example, the CCVS motif in PFL contains a pair of adjacent cysteine residues that facilitate pyruvate cleavage to formate with acetylation of one of the cysteine residues (see Fig. 3B, C), but class III RNRs in the NrdD2 subgroup also appear to employ side-by-side Cys residues (see Fig. 5B) for which the proposed roles are dissimilar (Fig. 5C). Likewise, a glutamate residue in the GCXE motif of 1,2-eliminases GDH and CutC serves as a catalytic base to deprotonate substrate (O’Brien et al., 2004, Bodea et al., 2016), but this motif is not diagnostic of the 1,2-eliminase subgroup, as HPAD contains the same GCXE motif and catalyzes decarboxylation by what appears to be a vastly different mechanism (Martins et al., 2011) (Fig. 6C). Additionally, class III RNRs in the NrdD2 subgroup are proposed to use a glutamate residue as a catalytic acid/base similar to GDH and CutC (Wei et al., 2014a), but here the glutamate is not on the Cys loop, although the more distantly related class I and II RNRs do contain a catalytically essential glutamate on the Cys loop in a CXE motif (Lawrence et al., 1999). The evolutionary relationships responsible for these differences and these similarities has been considered previously for RNRs (Torrents et al., 2002, Lundin et al., 2015) and for RNRs and PFL (Leppanen et al., 1999); however, as more and more sequence information becomes available and more GREs are characterized, it is likely that we will need to revisit the question of enzyme family evolution.

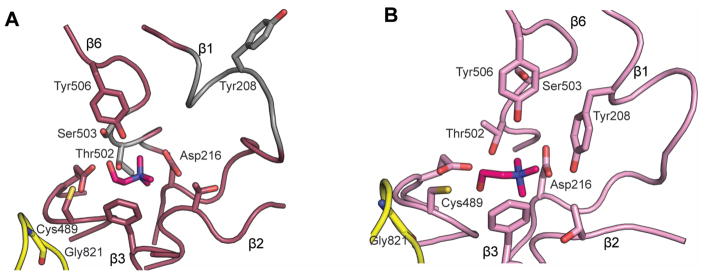

Predictions based on homology models

Creation of homology models for GREs with unknown structures that correctly predict active site composition and substrate-enzyme interactions is unusually difficult in this enzyme superfamily. For example, there are several important differences between the published choline-bound CutC structure and the homology model previously constructed based on GDH (Craciun et al., 2014, Bodea et al., 2016) (Fig. 8A). The active site architecture of CutC and GDH differ primarily at β1 (containing key residues Tyr208 and Asp216) and β6 (containing Thr502 and Ser503). β1 is interrupted by a short helix in both CutC and GDH, but due to low sequence similarity in this region and a single residue insertion, the homology model is shifted out of register within this helix. As a result of these sequence-level changes, Tyr208 is facing out of the active site in the homology model (Fig. 8A), whereas the crystal structure shows that this residue facing into the active site and making contact with substrate (Fig. 8B). In contrast, the position of Asp216 on one of the sheet-like regions of β1 is correctly modeled. Within β6, Thr502 and Tyr506 are placed in essentially the correct position in the model, but the backbone conformation of the loop between these residues is different (Fig. 8), resulting in Ser503 being located distal to the choline-binding site, instead of within it, as predicted by the model. It is notable that despite a relatively high overall sequence identity between the two enzymes (37%), the β-strands that line the active site have very low sequence identity and structural similarity.

Figure 8. Comparison of CutC structure with GDH-based CutC homology model.

A. Homology model of CutC (Bodea et al., 2016) created in Modeller using GDH as the starting model; choline (magenta) was docked using Schrodinger Suite 2012. Residues that differ substantially from the observed positions in the crystal structure are colored gray, with most signification differences observed for Tyr298, Thr502, and Ser503. B. The crystal structure of CutC bound to choline (magenta, PDB ID: 5FAU) in the same orientation as in A. A color version of this figure is available online.

Furthermore, the docking model of choline failed to identify what turned out to be important interactions between CutC and the choline substrate. Although general positioning of choline was validated by the crystal structure (Fig. 8), the choline hydroxyl group points away from the amide nitrogen of C489 in the homology model, instead of toward it, and is close (less than 3 Å) to Tyr506 and Ser503, neither of which form interactions with this substituent in the crystal structure (Bodea et al., 2016). Importantly, the abundance of CH–O interactions observed in the structure (Bodea et al., 2016) were not predicted by this model, although Asp216 does make one close interaction. In the homology model, the absence of Tyr208 from the active site creates an open cavity, leaving one entire face of choline without protein contacts. Tyr506 makes only van der Waals contacts with the methyl groups of choline instead of close CH–O interactions.

Probing mechanism and function with enzymology

Biochemical characterization is an established method for verifying enzyme function, but is often non-trivial for members of the GRE family. Challenges include difficulty in purifying functional activating enzymes, limited glycyl radical activation, and managing oxygen sensitivity of both the activase and the GRE. Activating enzymes that contain multiple iron-sulfur clusters, the functions of which are currently unknown (Selvaraj et al., 2014), appear to be particular onerous to purify and study (Qiao and Marsh, 2005, Li and Marsh, 2006b, Selvaraj et al., 2013). In the case of BSS, the purified BSS activating enzyme (BssD) has never been shown to be a functional AE (Qiao and Marsh, 2005, Li and Marsh, 2006b, Funk et al., 2014, Funk et al., 2015). Therefore, in order to probe BSS catalysis in vitro, cell-free extract of BssD from its native organism, Thauera aromatic, must be used (Qiao and Marsh, 2005, Li and Marsh, 2006b). Even when purification of a functional activating enzyme is successful, in vitro activation reactions results in at most 1 glycyl radical per dimer, complicating mechanistic and kinetic analyses.

As a result of these challenges, biochemical characterizations of newly discovered GREs are not completed quickly, and key mechanistic and structural questions in the GRE field can remain unanswered. Longstanding questions that are broadly relevant include: how do GREs and GRE-AEs interact; how exactly is a buried catalytic glycine residue exposed to a GRE-AE for activation? Is PFL-AE a good prototype for all GRE-AE? Although several GREs have now been structurally and biochemically characterized, PFL-AE remains the only structurally characterized GRE-AE (Vey et al., 2008). What is the molecular basis for the observed half-site activation of GREs? No more than one glycyl radical per GRE dimer has ever been observed by electron paramagnetic resonance, suggesting half-site reactivity. If, in fact, only one monomer of each GRE dimer is active, what is the function of the second monomer? As interest in the GRE family grows, it is likely that some or all of these questions will be answered. It is particularly important to resolve the issue of activation, i.e. whether a dimeric GRE with a single glycyl radical is fully active or 50% active.

Using bioinformatics as a tool

The rapidly growing identification of new sequences grossly outpaces biochemical and structural investigations (for many of the reasons outlined in the last section), thus creating a need to identify and prioritize enzymes for experimental investigations. In this regard, bioinformatics can be used as a tool for guiding attention towards the more abundant and/or potentially novel enzymes. Recently, Levin et al. presented a chemically guided profiling method for mapping enzyme superfamilies in specific human metagenomes, not only allowing for quantification but also prioritization of enzymes for future study based on their abundance and distribution (Levin et al., 2017). By utilizing this method for the GRE family in the human microbiome, they identified trans-4-L-hydroxyproline dehydratase (HypD), encoded by 360 bacterial genomes, including the human pathogens Clostridium difficile, Clostridium botulinum, and Treponema maltophilum. HypD is the most abundant previously uncharacterized GRE found in the human gut, and is the second most abundant GRE; PFL is the first (Levin et al., 2017). Many of the clostridial species which express HypD utilize Stickland fermentation, or amino acid fermentation, as their primary form of energy metabolism (Stickland, 1934, Stickland, 1935b, Stickland, 1935a), and previous studies have shown that hydroxyproline (Hyp) can be used as an electron acceptor for this pathway (Stickland, 1934, Stadtman and Elliott, 1957), although the enzymes that assimilate Hyp into Stickland fermentation remained unidentified. The discovery of HypD resolves this mystery, providing an explanation for how bacteria can use the abundant metabolite Hyp in energy-generating pathways. Interestingly, Hyp is available in large quantities in the human microbiome due to its presence in collagen, the most abundant protein in the diet. The identification of HypD is a great example of the power of a chemically-guided bioinformatic approach (Levin et al., 2017).

Through bioinformatics, we have also learned about the location of GREs within microbes. In particular, bioinformatics data on bacterial microcompartments (BMC) have revealed that GREs are the most common enzyme family associated with catabolic BMCs (Axen et al., 2014). However limited information is available about the function of these GRE-associated microcompartments (GRM). BMCs are proteinaceous organelles, which organize enzymes together within close proximity. The outermost shell acts as a semipermeable membrane isolating the BMC lumen from the cytosol, allowing charged and polar molecules to pass through (Kerfeld et al., 2010, Chowdhury et al., 2014). GRMs are predicted to contain a GRE, the associated GRE-AE, and downstream enzymes. Functional uses for GRMs remain unclear, although possibilities include controlling toxicity of harmful products (such as reactive aldehydes) and offering protection against oxygen (Axen et al., 2014). A foundation for experimental characterization of GRMs has been laid out by the classification of GRMs into five groups (GRM1-5) through bioinformatics studies (Zarzycki et al., 2015). The only characterized GREs predicted to be associated with BMCs are CutC (associated with the GRM1 and GRM2 loci) and PDH (GRM3 locus). The first experimental work investigating three core enzymes in a GRM3 (PDH, PDH-AE, and an aldehyde dehydrogenase that acts the product of PDH) was recently published (Zarzycki et al., 2017). The identification of new GRMs and characterization of existing GRMs, their organizational and functional benefits, represent an exciting research area.

Conclusions

Our understanding of the chemistry and biology of GREs has expanded in the past two decades, but there remain many questions as to how these enzymes function and are regulated. Recent studies have highlighted the prevalence and importance of these enzymes (Levin et al., 2017), but the vast majority of the enzymes in this family remain uncharacterized.

One motivation for characterizing GREs is that members of this enzyme family play vital roles in the primary metabolism of multi-drug-resistant pathogens such as Clostridium difficile and Clostridium boutlinum and thus may be promising antibiotic targets. There are no human counterparts to these enzymes, which may be advantageous in avoiding cross-reactivity. Furthermore, GREs common in the human gut and oral microbiota are known to have prominent roles in human disease. For example, HPAD product p-cresol has been implicated with chronic kidney disease (Bammens et al., 2006, Poveda et al., 2014), and CutC activity has been linked to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Dumas et al., 2006), cardiovascular disease (Wang et al., 2011, Tang et al., 2013), and trimethylaminuria (fish malodor syndrome) (Christodoulou, 2012). With the emerging interest in developing personalized medical approaches to treating patients, understanding how an individual’s unique microbial flora impacts therapeutic approaches deserves attention. On a more basic level, studying GREs prominent in the human microbiome will expand our understanding of the biochemistry that governs interactions between hosts and both commensal and pathogenic bacteria, a topic critical to human health yet poorly understood at the molecular level.

Finally, the GRE family plays prominent roles in bioremediation and industry. The natural ability of members of the XSS family to metabolize inert hydrocarbons allows for an environmentally friendly method of managing pollutants, such as toluene. Although hydrocarbon degradation is a beneficial process in natural oil-polluted environments, in industrial settings, contamination by XSS-containing microbes can be damaging to oil quality as well as to physical infrastructure. Some microbes grow so abundantly around oil refineries that they even clog oil pipes (Griebler and Leuders, 2009), which can lead to oil spills. The structural characterization of BSS could afford inhibitor design with the goal of preventing organisms from living inside oil refinery machinery. In addition, the environmental impact of the GRE family could be expanded by biochemically characterizing other members of the XSS family, which could reveal other hydrocarbon pollutants as substrates.

Another GRE, GDH, also holds potential for environmental and industrial utility: this enzyme can convert glycerol, a major byproduct of biodiesel production, into propane-1,3-diol, a valuable chemical that can be used as a monomer for plastics, cyclic compounds, and lubricants (Jiang et al., 2016). Since both proper glycerol disposal and synthesis of propane-1,3-diol through chemical methods are expensive yet necessary processes in industry, GDH offers an elegant yet cheap method for bioconversion of glycerol to propane-1,3-diol.

GREs perform fundamental, difficult, and often times long sought-after biochemical reactions in anaerobic bacteria. Although bioinformatics has accelerated our understanding of the widespread nature and prominence of the GRE family, biochemical and structural characterization of key members remains essential. Since GREs have been found to catalyze exciting reactions with vast implications on human health, the environment, and industry, discovery and characterization of uncharacterized GREs warrants further investigation.

Biographies

Lindsey R.F. Backman received her B.S. in Chemistry from the University of Florida in 2015. Lindsey is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Biological Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the group of Professor Catherine L. Drennan. Her research focuses on structurally and biochemically characterizing glycyl radical enzymes prominent in the human gut microbiome.

Michael A. Funk is currently a postdoctoral associate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in Professor Wilfred van der Donk’s laboratory. He obtained B.S. degrees in Biology and Chemistry from Vanderbilt University in 2008. He received his Ph.D. in 2015 from MIT for determining structures of radical enzymes in primary metabolism with Professor Catherine L. Drennan.

Christopher D. Dawson received his B.S. in Biology and B.A. in Neuroscience from the University of Virginia in 2013. Dawson is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the lab of Professor Catherine L. Drennan. His research focuses on the structural and biochemical characterization of allosteric regulation in anaerobic ribonucleotide reductases.

Catherine L. Drennan is a professor of Biology and Chemistry at MIT, and a professor and investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. She received an A.B. in Chemistry from Vassar College and a Ph.D. in Biological Chemistry from the University of Michigan, working in the laboratory of the late Professor Martha L. Ludwig. She was a postdoctoral fellow with Professor Douglas C. Rees at the California Institute of Technology. In 1999, she joined the faculty at MIT, where she has risen through the ranks to full Professor. Cathy’s research interests lie at the interface of chemistry and biology. Her laboratory combines X-ray crystallography with other biophysical methods in order to “visualize” molecular processes by obtaining snapshots of metalloproteins in action.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement:

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) GM069857 (C.L.D.), the NIH Pre-Doctoral Training Grant T32GM007287 (C.D.D.), the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. 1122374 (L.R.F.B.) and 0645960 (M.A.F.). C.L.D is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) Investigator.

References

- Acosta-Gonzalez A, Rossello-Mora R, Marques S. Diversity of benzylsuccinate synthase-like (bssA) genes in hydrocarbon-polluted marine sediments suggests substrate-dependent clustering. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:3667–76. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03934-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari U, Scheiner S. Magnitude and mechanism of charge enhancement of CH··O hydrogen bonds. J Phys Chem A. 2013;117:10551–62. doi: 10.1021/jp4081788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J, Westman M, Hofer A, Sjoberg BM. Allosteric regulation of the class III anaerobic ribonucleotide reductase from bacteriophage T4. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19443–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurelius O, Johansson R, Bagenholm V, Lundin D, Tholander F, Balhuizen A, Beck T, Sahlin M, Sjoberg BM, Mulliez E, Logan DT. The Crystal Structure of Thermotoga maritima Class III Ribonucleotide Reductase Lacks a Radical Cysteine Pre-Positioned in the Active Site. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axen SD, Erbilgin O, Kerfeld CA. A taxonomy of bacterial microcompartment loci constructed by a novel scoring method. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bammens B, Evenepoel P, Keuleers H, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y. Free serum concentrations of the protein-bound retention solute p-cresol predict mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1081–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A, Fritz-Wolf K, Kabsch W, Knappe J, Schultz S, Volker Wagner AF. Structure and mechanism of the glycyl radical enzyme pyruvate formate-lyase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:969–75. doi: 10.1038/13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A, Kabsch W. X-ray structure of pyruvate formate-lyase in complex with pyruvate and CoA. How the enzyme uses the Cys-418 thiyl radical for pyruvate cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40036–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beller HR, Edwards EA. Anaerobic toluene activation by benzylsuccinate synthase in a highly enriched methanogenic culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5503–5. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.12.5503-5505.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beller HR, Kane SR, Legler TC, Alvarez PJ. A real-time polymerase chain reaction method for monitoring anaerobic, hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria based on a catabolic gene. Environ Sci Technol. 2002;36:3977–84. doi: 10.1021/es025556w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beller HR, Spormann AM. Substrate range of benzylsuccinate synthase from Azoarcus sp. strain T. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;178:147–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandare R, Calabro M, Coschigano PW. Site-directed mutagenesis of the Thauera aromatica strain T1 tutE tutFDGH gene cluster. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:992–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegert T, Fuchs G, Heider J. Evidence that anaerobic oxidation of toluene in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica is initiated by formation of benzylsuccinate from toluene and fumarate. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:661–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0661w.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser M. Activation and regulation of the 4-hydroxyphenylacetate decarboxylase system from Clostridium difficile. Philipps-Universitat Marburg 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Bodea S, Funk MA, Balksus EP, Drennan CL. Molecular basis of C-N bond cleavage by the glycyl radical enzyme choline trimethylamine-lyase. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:1206–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckel W, Golding BT. Radical enzymes in anaerobes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:27–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan AV, Wawrik B, Ni Chadhain SM, Young LY, Zylstra GJ. Anaerobic alkane-degrading strain AK-01 contains two alkylsuccinate synthase genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Cendra MM, Juarez A, Torrents E. Biofilm modifies expression of ribonucleotide reductase genes in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheek J, Broderick JB. Adenosylmethionine-dependent iron-sulfur enzymes: Versatile clusters in a radical new role. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:209–226. doi: 10.1007/s007750100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury C, Sinha S, Chun S, Yeates TO, Bobik TA. Diverse bacterial microcompartment organelles. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2014;78:438–68. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00009-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou J. Trimethylaminuria: an under-recognised and socially debilitating metabolic disorder. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012;48:E153–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coschigano PW. Construction and characterization of insertion/deletion mutations of the tutF, tutD, and tutG genes of Thauera aromatica strain T1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;217:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciun S, Balskus EP. Microbial conversion of choline to trimethylamine requires a glycyl radical enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:21307–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215689109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craciun S, Marks JA, Balskus EP. Characterization of choline trimethylamine-lyase expands the chemistry of glycyl radical enzymes. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9:1408–13. doi: 10.1021/cb500113p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo A, Pedraz L, Astola J, Torrents E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exhibits Deficient Biofilm Formation in the Absence of Class II and III Ribonucleotide Reductases Due to Hindered Anaerobic Growth. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:688. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’ari L, Barker HA. p-Cresol formation by cell-free extracts of Clostridium difficile. Arch Microbiol. 1985;143:311–2. doi: 10.1007/BF00411256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson LF, Stabler RA, Wren BW. Assessing the role of p-cresol tolerance in Clostridium difficile. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:745–9. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas ME, Barton RH, Toye A, Cloarec O, Blancher C, Rothwell A, Fearnside J, Tatoud R, Blanc V, Lindon JC, Mitchell SC, Holmes E, Mccarthy MI, Scott J, Gauguier D, Nicholson JK. Metabolic profiling reveals a contribution of gut microbiota to fatty liver phenotype in insulin-resistant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12511–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601056103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliks M, Martins BM, Ullmann GM. Catalytic mechanism of the glycyl radical enzyme 4-hydroxyphenylacetate decarboxylase from continuum electrostatic and QC/MM calculations. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:14574–85. doi: 10.1021/ja402379q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliks M, Ullmann GM. Glycerol dehydration by the B12-independent enzyme may not involve the migration of a hydroxyl group: a computational study. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:7076–7087. doi: 10.1021/jp301165b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk MA, Judd ET, Marsh EN, Elliott SJ, Drennan CL. Structures of benzylsuccinate synthase elucidate roles of accessory subunits in glycyl radical enzyme activation and activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:10161–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405983111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk MA, Marsh EN, Drennan CL. Substrate-bound structures of benzylsuccinate synthase reveal how toluene is activated in anaerobic hydrocarbon degradation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22398–408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.670737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griebler C, Leuders T. Microbial biodiversity in groundwater ecosystems. Freshwater Biol. 2009;54:649–677. [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann O, Behrends A, Rabus R, Amann J, Halder T, Heider J, Widdel F. Genes encoding the candidate enzyme for anaerobic activation of n-alkanes in the denitrifying bacterium, strain HxN1. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:376–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms G, Rabus R, Widdel F. Anaerobic oxidation of the aromatic plant hydrocarbon p-cymene by newly isolated denitrifying bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1999;172:303–12. doi: 10.1007/s002030050784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heider J, Szaleniec M, Martins BM, Seyhan D, Buckel W, Golding BT. Structure and function of benzylsuccinate synthase and related fumarate-adding glycyl radical enzymes. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;26:29–44. doi: 10.1159/000441656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermuth K, Leuthner B, Heider J. Operon structure and expression of the genes for benzylsuccinate synthase in Thauera aromatica strain K172. Arch Microbiol. 2002;177:132–8. doi: 10.1007/s00203-001-0375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesslinger C, Fairhurst SA, Sawers G. Novel keto acid formate-lyase and propionate kinase enzymes are components of an anaerobic pathway in Escherichia coli that degrades L-threonine to propionate. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:477–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hioe J, Savasci G, Brand H, Zipse H. The stability of Calpha peptide radicals: why glycyl radical enzymes? Chemistry. 2011;17:3781–3789. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz S, Dirk LM, Yesselman JD, Nimtz JS, Adhikari U, Mehl RA, Scheiner S, Houtz RL, Al-Hashimi HM, Trievel RC. Conservation and functional importance of carbon-oxygen hydrogen bonding in AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15536–48. doi: 10.1021/ja407140k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz S, Trievel RC. Carbon-oxygen hydrogen bonding in biological structure and function. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41576–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.418574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Wang SZ, Wang YP, Fang BS. Key enzymes catalyzing glycerol to 1, 3-propanediol. Biotechnology for Biofuels. 2016:9. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0473-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalnins G, Kuka J, Grinberga S, Makrecka-Kuka M, Liepinsh E, Dambrova M, Tars K. Structure and function of CutC choline lyase from human microbiota bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:21732–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.670471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC. Bacterial microcompartments. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:391–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirdis E, Jonsson IM, Kubica M, Potempa J, Josefsson E, Masalha M, Foster SJ, Tarkowski A. Ribonucleotide reductase class III, an essential enzyme for the anaerobic growth of Staphylococcus aureus, is a virulence determinant in septic arthritis. Microb Pathog. 2007;43:179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappe J, Blaschkowski HP, Grobner P, Schmitt T. Pyruvate formate-lyase of Escherichia coli: the acetyl-enzyme intermediate. Eur J Biochem. 1974;50:253–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappe J, Neugebauer FA, Blaschkowski HP, Ganzler M. Post-translational activation introduces a free radical into pyruvate formate-lyase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1332–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappe J, Wagner AF. Glycyl free radical in pyruvate formate-lyase: Synthesis, structure characteristics, and involvement in catalysis. Methods Enzymol. 1995:258. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)58055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe H. Studies on the electrolysis of organic compounds. Ann Chim Pharm. 1849;69:257–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kube M, Heider J, Amann J, Hufnagel P, Kuhner S, Beck A, Reinhardt R, Rabus R. Genes involved in the anaerobic degradation of toluene in a denitrifying bacterium, strain EbN1. Arch Microbiol. 2004;181:182–94. doi: 10.1007/s00203-003-0627-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamattina JW, Keul ND, Reitzer P, Kapoor S, Galzerani F, Koch DJ, Gouvea IE, Lanzilotta WN. 1,2-propanediol dehydration in Roseburia inulinivorans; Structural basis for substrate and enantiomer selectivity. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:15515–15526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.721142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson KM, Andersson J, Sjoberg BM, Nordlund P, Logan DT. Structural basis for allosteric substrate specificity regulation in anaerobic ribonucleotide reductases. Structure. 2001;9:739–50. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00627-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CC, Bennati M, Obias HV, Bar G, Griffin RG, Stubbe J. High-field EPR detection of a disulfide radical anion in the reduction of cytidine 5′-diphosphate by the E441Q R1 mutant of Escherichia coli ribonucleotide reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999:96. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtio L, Goldman A. The pyruvate formate lyase family: sequences, structures, and activation. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2004;17:545–552. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzh059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppanen VM, Merckel MC, Ollis DL, Wong KK, Kozarich JW, Goldman A. Pyruvate formate lyase is structurally homologous to type I ribonucleotide reductase. Structure. 1999;7:733–44. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuthner B, Leutwein C, Schulz H, Horth P, Haehnel W, Schiltz E, Schagger H, Heider J. Biochemical and genetic characterization of benzylsuccinate synthase from Thauera aromatica: a new glycyl radical enzyme catalysing the first step in anaerobic toluene metabolism. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:615–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin BJ, Huang YY, Peck SC, Wei Y, Campo AM-D, Marks JA, Franzosa EA, Huttenhower C, Balskus EP. A prominent glycyl radical enzyme in human gut microbiomes metabolizes trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline. Science. 2017;355:eaai8386. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Marsh EN. Deuterium isotope effects in the unusual addition of toluene to fumarate catalyzed by benzylsuccinate synthase. Biochemistry. 2006a;45:13932–8. doi: 10.1021/bi061117o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Marsh EN. Mechanism of benzylsuccinate synthase probed by substrate and isotope exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 2006b;128:16056–7. doi: 10.1021/ja067329q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Patterson DP, Fox CC, Lin B, Coschigano PW, Marsh EN. Subunit structure of benzylsuccinate synthase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1284–92. doi: 10.1021/bi801766g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht S, Gerfen GJ, Stubbe J. Thiyl radicals in ribonucleotide reductases. Science. 1996;271:477–81. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]