Abstract

With rising prevalence of food allergy (FA), allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) for FA has become an active area of research in recent years. In AIT, incrementally increasing doses of inciting allergen are given with the goal to increase tolerance, initially through desensitization, which relies on regular exposure to allergen. With prolonged therapy in some subjects, AIT may induce sustained unresponsiveness, in which tolerance is retained after a period of allergen avoidance. Methods of AIT currently under study in humans include oral, sublingual, epicutaneous, and subcutaneous delivery of modified allergenic protein, as well as via DNA-based vaccines encoding allergen with lysosomal-associated membrane protein I. The balance of safety and efficacy varies by type of AIT, as well as by targeted allergen. Age, degree of sensitization, and other comorbidities may affect this balance within an individual patient. More recently, AIT with modified proteins or combined with immunomodulatory therapies has shown promise in making AIT safer and/or more effective. Though methods of AIT are neither currently advised by experts (oral immunotherapy [OIT]) nor widely available, AIT is likely to become a part of recommended management of FA in the coming years. Here, we review and compare methods of AIT currently under study in humans to prepare the practitioner for an exciting new phase in the care of food allergic patients in which improved tolerance to inciting foods will be a real possibility.

Keywords: Food allergy, subcutaneous immunotherapy, sublingual immunotherapy, oral immunotherapy, epicutaneous immunotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Food allergy (FA) affects 6% of adults1 and up to 8% of children. The prevalence of allergy and anaphylaxis is increasing.2,3 Standard management has been strict food avoidance and preparedness with an epinephrine auto-injector (EAI) in the event of a reaction.4 Despite efforts at avoidance, severe reactions may occur in up to a third of food allergic children.5 Given risk for accidental reactions and persistence of FA beyond childhood, there is an unmet need for therapies for FA. A number of allergen-specific methods are being studied, and may become commercially available in the coming years. In this review, we will discuss food allergen-specific immunotherapies (AITs) that are being evaluated in humans.

SECTION 1: WHAT ARE THE METHODS OF AIT FOR FA?

AIT utilize frequent delivery of allergen via various routes to induce tolerance. Food AITs currently under study include oral immunotherapy (OIT), sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT), and subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) with modified allergen, as well as lysosomal-associated membrane protein (LAMP)-DNA based vaccines. An overview of these AIT modalities is provided below and compared in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of allergen-specific immunotherapies for food allergy currently under study in human subjects.

| Features | OIT | SLIT | EPIT | SCIT with hypoallergen* | LAMP-DNA vaccine* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food allergens | Peanut, cow's milk, egg, wheat, multi-food | Peanut, cow's milk, hazelnut, peach | Peanut, cow's milk | Peanut, fish | Peanut |

| Stage of study | Phase I-IV | Phase I-III | Phase I-III | Phase I-II | Phase I |

| Typical protocol | Initial dose-escalation day; doses administered daily throughout protocol, with bi-weekly dose increases during build-up phase (months), followed by maintenance (months-years) | Daily patch application for increasing intervals until 24 hour per day maintenance (years) | Weekly incrementally increasing doses | Current trial: 4 doses every 2 weeks | |

| Maintenance dose | Daily; 300 mg to 4 g | Daily; 2 to 7 mg | Daily; 50 to 500 µg | Weekly 60 ng | Unknown |

| Observed doses | Initial dose escalation; up-dosing every 1 to 2 weeks | Up-dosing every 1 to 2 weeks | Initiation and periodic observation | All; typically weekly for build-up and monthly for maintenance | All are observed |

| Dosing restrictions | Take with food; avoid physical activity 2 hours after; withhold during illness | Avoid eating 30 minutes following dose | none | Period of in-office observation following each dose | Under observation in the office |

| Notable advantages | Improved efficacy compared to SLIT and EPIT; Cost efficient | Improved safety profile compared to OIT | Best safety profile of AIT for food allergy under study in humans; Ease of administration | Dosing only once per week; Observed dosing may improve compliance | Potential to induce tolerance with limited number of doses |

| Notable disadvantages | Frequent office visits during up-dosing; frequent AE which may include anaphylaxis; risk of EoE | Frequent AE; theoretical risk of EoE | Limited data: appears to have reduced efficacy compared to other modalities | Frequent office visits during up-dosing; administered by injection | Administered by injection |

AE, adverse event; AIT, allergen-specific immunotherapy; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; EPIT, epicutaneous immunotherapy; LAMP, lysosomal-associated membrane protein; OIT, oral immunotherapy; SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy.

*Very limited data in humans.

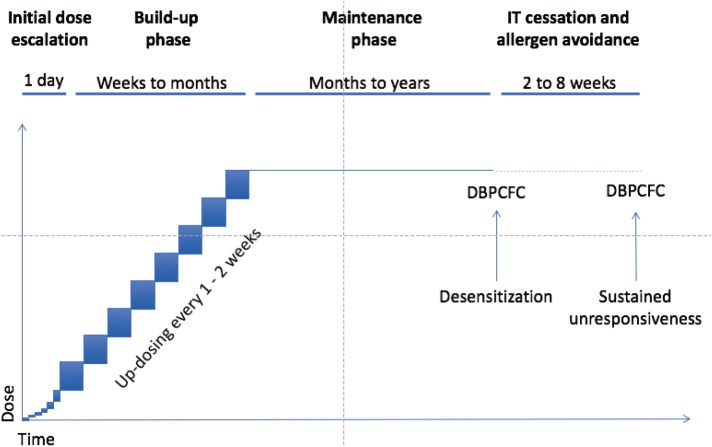

OIT and SLIT

In OIT, native or modified food allergen is ingested; whereas in SLIT, liquid allergen extract is applied under the tongue. SLIT and OIT respectively start with sub-threshold doses in 0.0001 µg- and 0.1 mg-range, which are increased under physician supervision during an initial rapid dose-escalation day up to 0.01 µg-range and mg-range. The highest tolerated dose after initial dose-escalation may be repeated on the following day to confirm it will be safely tolerated during daily doses at home. This is followed by a build-up phase during which daily doses are increased every 2 weeks under physician supervision up to maintenance doses in mg-range for SLIT and gram-range for OIT. Daily maintenance dosing is continued for months to years.

EPIT

In EPIT, 50–500 µg (usually 250 µg) of food protein electrosprayed onto a patch is applied to the upper arm or interscapular space. EPIT protocols typically start with 2 hours of patch application under clinician supervision in the office. Thereafter, daily patch application continues at home, with duration of application increased incrementally up to 24 hours per day. During maintenance, a new patch is applied daily and worn 24 hours per day for 1 or more years.6,7

SCIT

In SCIT, allergen is administered by subcutaneous injection in incrementally increasing doses under clinical supervision. Current SCIT trials utilize alum-adsorbed hypoallergen which has been modified chemically or with site-directed mutagenesis to reduce immunoglobulin (Ig) E-binding capacity.8

LAMP-DNA vaccines

In LAMP-DNA vaccines, DNA encoding allergen is administered in bacterial plasmid vectors, which express both the allergen epitope and LAMP-I for enhanced immunogenicity. They are administered by intramuscular or intradermal injection, every 2 weeks for a limited number of doses.

SECTION 2: IMMUNE MECHANISMS

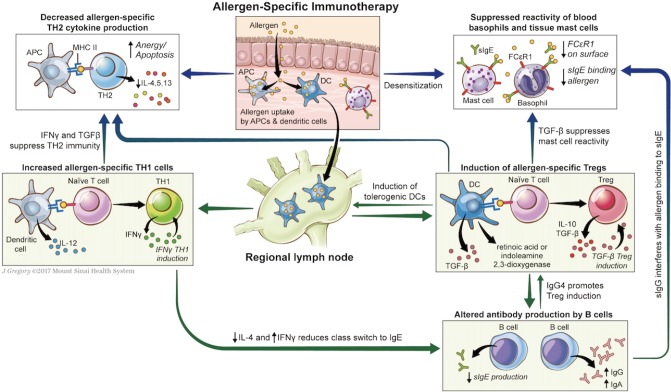

Immune mechanisms by which AIT may induce tolerance are not fully elucidated. The observed changes in immune function (Table 2) appear to hinge on altered allergen-specific T-cells responses, with induction of T-regulatory cells (Tregs) and suppression of TH2 immunity. Mechanisms of alteration in T-cell phenotype through AIT are discussed below and summarized in Fig. 1.

Table 2. Immunomodulation in allergen-specific immunotherapy.

| Immune parameter | Functional correlate |

|---|---|

| ↓SPT wheal diameter | Decreased mast cell reactivity |

| ↓CD63 expression in basophil activation test | Decreased basophil reactivity |

| Initial ↑sIgE, followed by sustained ↓sIgE | Altered antibody isotype production by B cells |

| ↑sIgG, particularly ↑sIgG4 | |

| ↑sIgA (limited to OIT and SLIT) | |

| ↓IL-4 and IL-13 production by PBMCs | Suppression of TH2 immunity |

| ↑IFN-γ production by production by PBMCs | Induction of TH1 CD4+ T cells |

| ↑IL-10, TGF-β production by PBMCs | Induction of T-regulatory cells |

| ↑FoxP3+CD25+CD4+ T cells |

Fig. 1. Putative mechanisms of tolerance induction in allergen-specific immunotherapy. In allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT), native or modified allergen is taken up by dendritic cells which migrate to regional lymph nodes, where they induce naïve T cells to regulatory T cell phenotype, through presentation of the allergen in context of MHC, secretion of cytokines such as TGF-β, generation of retinoic acid and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and other mechanisms. Secretion of cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β suppress TH2 immunity and mast cell reactivity, reduce sIgE synthesis, and may increase sIgG and sIgA synthesis. AIT, particularly with LAMP-DNA vaccines, may also enhance tolerance through increased TH1 immunity: presentation of allergen by dendritic cells in context of MHC to naïve T cell may induce TH1 commitment particularly in presence of costimulators; production of IFN-γ by TH1 cells suppresses TH2 responses and reduces class switch to IgE. Other mechanisms of AIT may include increased anergy and apoptosis of TH2 cells through persistent antigenic stimulation.

Natural tolerance acquisition and that conferred by AIT with native allergen appear to occur through induction of Foxp3+ Tregs. Antigen uptake by immature tissue-resident dendritic cells (DC) in the absence of costimulatory signals results in DC-mediated Treg induction, through secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines and other mechanisms.9,10 These induced-Tregs suppress allergic responses through secretion of inhibitory cytokines (interleukin [IL]-10, IL-35, and transforming growth factor [TGF]-β), which further amplifies Treg induction. Tregs also express surface receptors which alter DC function and induce target cell senescence.11

Immunotherapy appears to induce a shift away from TH2-predominant immune responses, with reduced allergen-specific production of TH2 cytokines.6,12,13,14,15,16 This may occur not only through the immunosuppressive effects of Tregs as elaborated above, but also through a shift towards TH1 immunity.6,17,18 TH1 cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-γ specifically inhibit TH2 immunity and IgE production. Alternative mechanisms include anergy and deletion of allergen-specific TH2 cells through repeated and frequent exposure to high doses of allergen.19

OIT

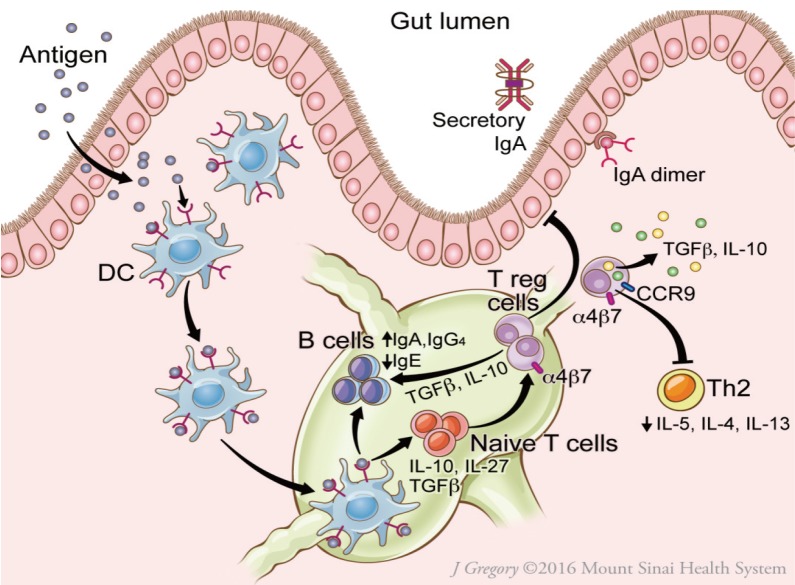

OIT utilizes the mechanisms underlying oral tolerance, resulting in suppression of allergic responses (Fig. 2). Oral tolerance is likely dependent on induction of Tregs within gut-associated lymphoid tissue.9,20 The steps through which this occurs include delivery of antigen to lamina propria DC by goblet cells (or other mechanisms); antigen uptake by CD103+DC in the intestinal lamina propria; CCR7-directed migration of DC to mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs); and interaction between DC and T-lymphocytes within MLNs.9,20 B-regulatory cells may also play a role in tolerance induction.21 The role of Tregs, B-regulatory cells, and DCs in oral tolerance has recently been reviewed in detail.20

Fig. 2. Putative mechanisms of oral tolerance induction in the gut. On passage through the epithelial barrier, food protein allergen is captured by the dendritic cell (DC). The DC migrates to the nearby mesenteric lymph nodes and produces TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-27, which induce T regulatory cells (Tregs) and promote secretion of IgA and IgG4 by B cells. Tregs express surface receptors CCR9 and α4β7 integrin, which direct migration to the gut. Tregs secrete immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β, which reinforce tolerance. Reprinted from Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice (Volume 5), Gernez Y and Nowak-Wegrzyn A, “Immunotherapy for Food Allergy: Are we there yet?”, Page 253, 2017, with permission from Elsevier.

OIT is associated with reduced skin prick test (SPT) wheal diameter and reduced basophil reactivity, initial increase followed by a gradual decrease in antigen-specific IgE, sustained increase in antigen-specific IgG4 and antigen-specific IgA, decreased allergen-specific production of TH2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-13), increased allergen-specific production of TH1 (IFN-γ) and Treg cytokines (TGF-β), and Treg induction.6,17,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 It appears however that some of these immunologic changes may be transient, with reversal on withdrawal of therapy and sometimes during maintenance.23,27

SLIT

SLIT utilizes the tolerogenic environment of the oral mucosa. Langerhans cells (LC; skin- and mucosa-homing DC) rapidly take up antigen, which has been transported across sublingual ductal epithelial cells.29 LC migrate to local lymph nodes, where they present allergen to naïve T cells, inducing Tregs through secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β.30

SLIT trials for FA provide evidence of Treg induction, and reduced TH2 cytokine production, that may reverse on cessation or during maintenance.27 SLIT trials report reduced basophil reactivity, reduced SPT wheal diameter, and increased antigen-specific IgA and IgG4/IgE ratio.26,27,31

EPIT

EPIT is purported to induce tolerance through prolonged application of antigen to intact, non-inflamed skin. In mice, antigen applied to skin is taken up by LC in the stratum corneum and transported to draining lymph nodes, where these LC induce Foxp3+ Tregs locally.32 Treg induction also appears to occur distally with generation of gut-homing LAP+Foxp3− Treg cells, which provide sustained protection against anaphylaxis through direct TGF-β-dependent Treg suppression of mast cell activation.33

In the first clinical trials of EPIT for FA, treated subjects had increased IgG4/IgE ratios, with trends towards decreased basophil reactivity and decreased TH2 cytokine responses. Unlike OIT and SLIT, allergen-specific IgE did not change significantly with EPIT compared to controls.6,34

SCIT

The mechanisms underlying tolerance induction for SCIT with alum-adsorbed hypoallergen may differ from those for SCIT with native allergen. In SCIT with native allergen, immune tolerance is induced by similar mechanisms described above, with antigen-uptake by immature subcutaneous DC, migration of DC to local lymph nodes, Treg induction by tolerogenic DC, and Treg-mediated suppression of TH2 immune responses.35 In SCIT using hypoallergen, alum-adsorption provides a costimulatory signal that promotes a TH1 response, which also serves to inhibit TH2 immunity. In murine and rabbit studies, subcutaneous immunization with hypoallergenic carp parvalbumin (Cyp c 1) resulted in increased sIgG and decreased sIgE antibodies; and inhibition of IgE-binding, basophil degranulation, and allergic symptoms on challenge.36,37

In the only published results of SCIT with hypoallergen for FA in humans, a 2017 abstract reported evidence of immunomodulation with increased peanut-specific IgG4 in subjects treated with subcutaneous injection of chemically modified alum-adsorbed peanut (HAL-MPE1) compared to controls.38

LAMP-DNA vaccines

LAMP-Vax is a next-generation DNA vaccine platform designed to stimulate an immune response against a particular protein, by injecting the DNA encoding the protein. After vaccine administration, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) take up the vector, which translates DNA into allergen associated with LAMP-I.39 LAMP-Vax DNA immunization contrasts with the immune response to conventional DNA vaccines, which are processed and primarily presented through major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I and elicit a cytotoxic T response. LAMP-Vax DNA immunization initiates a more complete immune response, including antibody production, cytokine release, and critical immunological memory. In the C3H/HeJ peanut allergic mice (sensitized via oral ingestion of peanut and cholera toxin), intradermal injection of 50 µg ASP0892 attenuated allergic symptoms during peanut challenge as indicated by lower disease scores and higher body temperature compared to vector control, reduced peanut-specific IgE levels and increased peanut-specific IgG2a levels.39,40

There is currently an ongoing phase I, randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate safety, tolerability, and immune response in adults allergic to peanut after receiving intradermal or intramuscular injection of ASP0892 (ARA LAMP-Vax), a single multivalent peanut (Ara h1, h2, h3) LAMP-DNA Plasmid Vaccine (NCT02851277).

SECTION 3: DESIGN OF AIT CLINICAL TRIALS

With OIT, SLIT, and EPIT being the focus of most published AIT clinical trials, much of the below discussion is based on published data evaluating these therapies. A general schematic of OIT and SLIT is provided in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Typical protocol for oral and sublingual immunotherapy. Initial doses of OIT and SLIT are generally given under medical supervision. Initial dose escalation day(s) starting at subthreshold dose with increasing doses given every 30 minutes over several hours is more common for OIT than for SLIT. Highest tolerated dose given under observation is then continued daily at home, and increased every 1 to 2 weeks under supervision during the build-up phase. The dose achieved at the end of the build-up is continued daily during a maintenance phase. After a few months or years of maintenance, double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) to the food is performed to assess for desensitization. Daily dosing may then be discontinued for a period of 4–12 weeks and reintroduced during DBPCFC, to assess sustained tolerance (SU). Reprinted from Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice (Volume 5), Gernez Y and Nowak-Wegrzyn A, “Immunotherapy for Food Allergy: Are we there yet?”, Page 253, 2017, with permission from Elsevier.

Goals of therapy

While the most desired outcome of AIT would be permanent tolerance, clinical trials investigating immunotherapies for FA typically use practical endpoints of desensitization and sustained unresponsiveness (SU). Desensitization is a temporary state of hyporesponsiveness, which is induced and maintained by frequent (daily) exposure to the offending antigen. Immune reactivity may return upon withdrawal of antigen exposure for a sufficient period of time. SU is a prolonged antigen hyporesponsiveness which persists after a period (typically 2–12 weeks) of cessation of therapy and avoidance of allergen.

Design of AIT clinical trials

Shared features of AIT clinical trials

Clinical trials share a number of features. For recruitment, entry criteria typically include a history of reaction to the food or physician-diagnosed FA, with evidence of IgE-sensitization. Typical exclusion criteria include history of life-threatening anaphylaxis, poorly controlled asthma, other form of concomitant immunotherapy, medications that either suppress immune response or increase risk of reactions, and certain chronic conditions. Most of the rigorous studies will require a double-blind placebo-controlled oral food challenge (DBPCFC) to determine the threshold prior to initiation of therapy, to confirm presence of the FA, and to eliminate subjects who are tolerant of the food or reactive to placebo.

For randomized, controlled trials (RCT), subjects are then randomized to AIT or to the control group (placebo and/or strict avoidance of allergen). To evaluate immunomodulation on AIT (Section 3), clinical trials may perform allergen-specific evaluation prior to AIT initiation, at various time-points during the study and at the conclusion of therapy. Therapy protocols are undertaken for various forms of AIT as described in Section 1. Adverse events (AEs) are monitored through out the trial. Subjects may withdraw for any reason. Common reasons include persistent and/or severe AE, anxiety related to doses or oral food challenge (OFC), inability to comply with protocols, or new medical problems or medications.

At the conclusion of therapy, desensitization is typically evaluated with DBPCFC, and reported as the portion of subjects tolerating standardized dose of food or as the increase in the maximum tolerated dose of allergen compared to prior to IT. For those trials also evaluating SU, subjects avoid therapy as well as native food for a period (typically 2–12 weeks) after which DBPCFC is again undertaken. Some trials may report consumption of the food years out from therapy, to evaluate long-term success with AIT.

Divergent features of AIT trials

Direct comparison of results of various studies is hampered by variation in trial design. The following frequently differ between trials: allergic profile of individuals enrolled in the trial; duration of initial dose-escalation, build-up, and maintenance phases as well as avoidance period prior to SU-OFC; daily maintenance dose; and dose administered during OFCs to define desensitization and SU. Though all trials report moderate or severe AE as well as administration of epinephrine, reporting of minor AE may differ, with some trials reporting only what are deemed clinically-relevant dose-related AE, and others with a lower threshold to report minor AE.

SECTION 4: ORAL IMMUNOTHERAPY TRIALS

Overview of OIT trials

OIT remains a subject of active investigation, with most trials demonstrating efficacy limited by safety and compliance. Published studies have evaluated OIT with major food allergens, including milk, egg, peanut, and wheat, with safety and efficacy varying by food allergen. In recent years, investigators have evaluated OIT with modified proteins, with multiple foods, and/or combined with immunomodulatory agents.

Efficacy

Oral administration of gradually increasing quantities of food protein during OIT effectively induces desensitization in a majority of food allergic subjects, provided they can tolerate and comply with therapy. A portion of those achieving desensitization go on to demonstrate SU 2–12 weeks post-OIT.12,24,41 For those achieving SU, long-term follow-up studies demonstrate continued consumption of offending food months to years after OIT completion.42,43

Safety

The use of OIT in routine clinical practice has been limited by its AE, which are most often mild, but can include anaphylaxis, chronic gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort, and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Safety varies by allergen, with milk carrying increased risk of AE compared to peanut, egg, and perhaps wheat. The majority of subjects experience some symptoms with OIT, including oropharyngeal pruritus, rhinitis, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, urticaria, angioedema, atopic dermatitis flare, cough, and wheeze. Most of the time, these are non-severe and self-resolving; sometimes administration of antihistamine, short-acting beta agonists, or systemic steroids is required. Though uncommon, most OIT trials are accompanied by a few severe reactions requiring administrations of epinephrine. Persistent, frequent, or severe symptoms often interfere with adherence and result in drop-outs accompanying virtually every OIT trial. While severe reactions occur most often during initial dose escalation and build-up, they can occur with home administration of previously tolerated doses. A major development in reducing IgE mediated AE with OIT has been concomitant administration of omalizumab, discussed in section “OIT with omalizumab.”44

Cofactors

Adverse reactions occurring with previously tolerated doses often occur in the setting of cofactors which lower allergic threshold, such as viral infection, febrile illness, active allergic rhinitis in the pollen season, physical exertion, or administration on an empty stomach.45,46,47 To address cofactors, most OIT protocols advise dose adjustments in the setting of viral infection, avoidance of exertion in the hours following a dose, and administration after a full meal.

EoE

A meta-analysis by Lucendo and colleagues48 concluded that EoE may develop in up to 2.7% of OIT subjects, and often resolves on withdrawal of OIT. It is possible that more subjects develop OIT-related EoE than is reported, as some discontinuing OIT for GI symptoms suspicious for EoE are not evaluated with endoscopy.47 It is not clear whether OIT unmasks EoE to the culprit food or increases the likelihood of EoE.

Adherence

OIT requires significant commitment from families and patients in order to adhere to therapy. Families and patients need the flexibility in their schedules and access to transportation to return many times during the protocol. Initial dose escalation may require a full day (or several days depending on the protocol) in an inpatient setting. For build-up phases (which may take weeks to months), patients must return every 1 to 2 weeks for observed dosing. Finally, subjects must take their dose every day for months to years; for patients with taste aversion, parents and patients with anxiety, and families with significant life events, this may prove challenging. As a consequence, most OIT studies report withdrawals from the protocol for issues not specifically related to AE.

Quality of life (QoL)

Despite its risks and frequent adverse effects, OIT appears to improve QoL,49 alleviating risk with accidental exposure, food-related anxiety, and social and dietary limitations.

Cost-effectiveness

Peanut-OIT with probiotic was found to be cost efficient compared to avoidance in a long-term economic model, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $2,142 per quality-adjusted life year. However, peanut-OIT subjects were more likely to experience peanut-related allergic reactions and anaphylaxis; this appeared to be of particular relevance to subjects who experience a low rate (<25%) of allergic reactions related to accidental exposure, or when probability of SU was less than 68%.50

Details of the specific OIT-studies are presented in the tables; cow's milk (CM; Tables 3 and 5), egg (Tables 4 and 5), peanut (Table 6), and wheat (Table 7).

Table 3. Representative milk oral immunotherapy clinical trials.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk OIT, open-label in highly sensitized | 21 subjects | 6 months | Milk OIT induced desensitization to daily 200 ml dose in 71% of subjects considered to have severe cow milk allergy | No reported EAI 14% developed moderate symptoms on first dose 14% had dose-limiting symptoms during build-up |

| Meglio et al. 2004 | 5–10 years | 200 mL | ||

| Milk and egg OIT vs avoidance in young children, RCT | 14 milk 11 egg 20 avoidance |

Mean 21 months | 64% of OIT subjects were able to integrate allergenic food into the diet, compared to 35% of avoidance group (P=0.05); 36% of OIT group demonstrated 2-month SU | No severe AE. No EAI 9 AE-related withdrawals All active had AE, 4 with moderate AE. Among controls, 5 had moderate symptoms on accidental exposures |

| Staden et al. 2007 | Median 2.5 years (range 1-12 years) | 100 mL cow milk 1.6 g egg |

||

| Milk OIT vs placebo, RCT | 12 active 7 placebo |

6 months | Milk OIT induced desensitization, with median eliciting dose in active subject 5,140 mg compared to 40 mg in placebo (P<0.001) | 1% of active doses elicited multi-system AE, vs 0 in placebo (P=0.01); 1 of 12 active withdrew due to AE |

| Skripak et al. 2008 | 6–17 years | 15 mL | ||

| Milk OIT, Open-label follow up of Skripak 2008. | 15 subjects, tolerant of 75 mL after above OIT | Median 4 months open-label following 6 months blinded | Milk OIT induced desensitization to between 90 and 480 mL in 87%, with safety concerns | EoE in 1 subject. 6 EAI in 4 subjects. Multi-system reaction decreased from 11% in first 3 months to 4.8% in subsequent month |

| Narisety et al. 2009 | 15 mL | |||

| Milk OIT with gradual build-up vs placebo, RCT | 15 active 15 placebo |

4.5 mo | Milk OIT with gradual outpatient build-up induced desensitization in 66% of active, vs 0 in placebo, with safety concerns | Among active group, 3 patients experienced severe AE with 2 EAI; 7 mild AE; 3 had no AE |

| Pajno et al. 2010 | 4-10 years | 200 mL | ||

| Milk OIT vs placebo, RCT in young children | 30 active 30 placebo |

1 year | Among young subjects, milk OIT induced 200 mL-desensitization in 90% on active, vs 23% in placebo, with safety concerns | 2 EAI. 37% of subjects experienced multi-system reaction. 2 AE-related withdrawals |

| Martorell et al. 2011 | 2-3 years | 200 mL | ||

| Low-dose OIT vs avoidance, in highly sensitized | 12 active 25 avoidance |

1 year, with 5-day inpatient build-up | In a highly sensitized group, low-dose OIT protocol induced 3 mL-desensitization in 58% of active and 14% of controls (P=0.018); and 25 mL-desensitization in 33% of active vs 0 of controls (P=0.007), with good safety profile | 1 EAI after home dose, given for cough; no AE-related withdrawals |

| Yanagida et al. 2015 | 6-13 years | 3 mL |

AE, adverse event; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; ITT, intention to treat; OIT, oral immunotherapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SU, sustained unresponsiveness.

Table 5. Oral immunotherapy with modified egg and milk proteins.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baked milk OIT, open-label, in highly sensitized subjects | 15 milk OIT failures reactive to 30 mg milk | 12 months | Among highly reactive subjects, only 20% tolerated 1.3 g/day of baked milk; those completing 12 months did have increase in challenge threshold to unheated milk | 2 EAI for 2 episodes of anaphylaxis after home dosing. AE occurred at doses previously tolerated >1 mo. 53% withdrew due to IgE-mediated reactions |

| Goldberg et al. 2015 | 6–12 years | 1.3 g baked milk/day | ||

| Hydrolyzed egg OIT, vs placebo, RCT | 15 active 14 placebo No entry OFC |

6 months | OIT with hydrolyzed egg not effective over placebo in inducing desensitization | 7 dose-related AE in active vs 2 in placebo. No severe AE or EAI |

| Giavi et al. 2016 | 1–5 years | 9 g hydrolyzed egg | ||

| Baked egg OIT, open-label | 15 subjects | 2–9 months | Only 53% were able to complete the protocol. All who completed protocol subsequently tolerated boiled egg | No moderate or severe AE. No EAI. 7 were intolerant of first dose and 5 tolerated partial doses |

| Bravin et al. 2016 | 5–17 years | 6.25 g baked egg | ||

| Ultra-high temperature treated milk OIT, open-label | 20 subjects | 18–36 months | 70% achieved desensitization to 200 mL cow milk within 24 months | 57% among the 14 achieving desensitization had mild reactions. Among the 6 who did not, there were more severe reactions (including anaphylaxis) and 2 AE-related withdrawals |

| Perezábad et al. 2017 | 1–11 years | 25 g goat and sheep milk sheep (30% protein) |

AE, adverse event; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; ITT, intention to treat; OFC, oral food challenge; OIT, oral immunotherapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 4. Representative egg oral immunotherapy clinical trials.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egg OIT, open-label | 7 subjects | 24 months | Among subjects without history of anaphylaxis, 24-month egg OIT induced 8 g-desensitization in 4 of 7, with good safety profile | No severe AE. No EAI. Mild AE during initial dose escalation; 1 reaction during build-up; none during maintenance |

| Buchanan et al. 2007 | 1–7 years | 0.3 g/day | ||

| Egg OIT in young children: see Staden et al. 2007 in Table 3 | ||||

| Egg OIT, open-label | 8 subjects | 18–40 months | Using a modified build-up protocol with IgE-de-pendent up-dosing, 75% achieved 3.9 g-desensitization achieved, with good safety profile | No severe AE. No EAI. Symptoms in 83% on initial dose escalation; 1 required SABA. No reactions on maintenance |

| Vickery et al. 2010 | 3–13 years | maximum 3.6 g/day | ||

| Egg OIT vs placebo, RCT | 40 active 15 placebo |

22 months | 55% on active vs 0 on placebo achieved 5 g-de-sensitization after 10 months OIT; After 22 months OIT, 75% achieved 10 g-desensitization; 28% achieved 2 month-SU |

No severe AE. No EAI. Symptoms with 25% of active vs 4% placebo. 5 AE-related withdrawals in active, vs 0 in placebo |

| Burks et al. 2012 | 5–11 years | 2 g/day | ||

| Egg OIT, long-term follow-up of Burks et al. 2012 | as above | Up to 4 years | With prolonged OIT, 50% of active subjects achieved 4 to 6-week SU to 10 g. 1 year after study conclusion, 64% of active and 25% of placebo were consuming egg (P=0.04) | No severe AE. No EAI. 12 of 22 active still reporting mild symptoms with egg at years 3 to 4 |

| Jones et al. 2016 | As above | |||

| Short-course open-label egg OIT vs placebo, RCT | 17 active 14 placebo |

4-month OIT with 5 months egg-containing diet | Abbreviated OIT protocol induced 4-g desensitization in 94% (compared to 1 of 14 in placebo), with 29% achieving 3-month SU | 1 EAI during desensitization phase. 1 reaction requiring SABA and steroid during maintenance |

| Caminiti et al. 2015 | 4–10 years | 4 g | ||

| Short-course open-label egg OIT, vs avoidance, | 30 active 31 avoidance |

3-month OIT | Abbreviated OIT protocol induced 2.8 g desensitization in 93%, with 1 month-SU in 37% (vs 1 of 31 placebo), with acceptable safety profile. All with SU were consuming at 36 months post-OIT | Symptoms with 5.9% of active doses. 5 episodes respiratory distress with 1 EAI in active group |

| Escudero et al. 2015 | 5–17 years | 1 undercooked egg (3.6 g) | ||

| Highly sensitized subjects, low-dose egg OIT vs avoidance, RCT | 21 active 12 avoidance |

12 months, with 5-day inpatient dose escalation | Among subjects with history of anaphylaxis or sIgE >30 kIU/L, a modified, low-dose protocol induced 2 week-SU to 0.2 g in 71% (vs 0 of 12 controls); and SU to 1.8 g in 33%, with acceptable safety profile | No severe AE. No EAI. Symptoms with 6.5% of home doses. 2 AE-related withdrawals |

| Yanagida et al. 2016 | 6–19 years | 0.1–0.2 g scrambled egg | ||

| High dose egg OIT vs placebo, RCT | 19 active 14 placebo |

5 months; with 5-day build-up | A high-dose, abbreviated protocol with inpatient build-up induced desensitization to 1 under-cooked egg in 89% of active subjects, vs 0 of placebo | During build-up, 2 episodes of anaphylaxis and 2 EAI. No severe AE during maintenance |

| Perez-Rangel et al. 2017 | Mean 10.4 years | 1 undercooked egg (=3.6 g powder)/48 hours | ||

AE, adverse event; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; ITT, intention to treat; OIT, oral immunotherapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SU, sustained unresponsiveness.

Table 6. Representative peanut oral immunotherapy clinical trials.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut OIT open-label | 39 subjects | 36 months | Peanut OIT induced 3.9 g-desensitization in 74% of subjects with acceptable safety | 3.7% of home doses were accompanied by symptoms; 0.8% requiring treatment, with 2 EAI 4 AE-related withdrawals |

| Jones et al. 2009 | 1–16 years | 1.8 g | ||

| Peanut OIT open-label | 23 subjects | Median 9 months, with 7-day rush | Using a shorter protocol, 61% reached target daily dose of 500 mg. At 1-wk SU OFC, median highest tolerated dose was 1 g. Safety concerns persist despite lower target maintenance, primarily among asthmatics | 0.3% of doses accompanied by AE. 4 AE-related withdrawals all due to asthma exacerbations, with one hospitalization |

| Blumchen et al. 2010 | 3–14 years | 0.5 g minimum | ||

| Peanut OIT vs placebo, RCT | 19 OIT 9 placebo |

12 months | Peanut OIT induced 5-g desensitization in 84% of active subjects, vs 0 on placebo (P<0.001), with acceptable safety profile | 2 EAI with initial dose escalation; no EAI after home dose (except in placebo arm) 3 AE-related withdrawals |

| Varshney et al. 2011 | 1–16 years | 5 g | ||

| Peanut OIT open-label | 22 subjects | 9–17 months | Peanut OIT with lower maintenance dose of 800 mg induced 6.6 g-desensitization in 64% of subjects, with acceptable safety profile | No EAI. 0 AE-related withdrawals. 86% experienced some AE with doses. 0.4% of build-up & 0.3% of maintenance doses required SABA |

| Anagnostou et al. 2011 | 4–18 years | 0.8 g | ||

| Peanut OIT vs avoidance, RCT | 49 OIT 46 avoidance |

6 months | In a study inclusive of subjects with life-threatening anaphylaxis to peanut, peanut OIT induced 1.4 g-desensitization in 50% of active subjects, compared to 0 on avoidance, with acceptable safety profile | 2 home EAI in 1 participant Wheeze after 0.41% of doses in 22% of participants; 4 AE-related withdrawals |

| Anagnostou et al. 2014 | 7–16 years | 0.8 g | ||

| Follow up of Jones 2009; Peanut OIT open-label |

39 subjects | 22 months | 4 week SU to 5 g achieved in 31% of enrolled subjects and 50% of subjects completing the protocol. All subjects with SU were consuming peanut 40 months post-OIT | 6 AE-related withdrawals |

| Vickery et al. 2014 | 1–16 years | 4 g max | ||

| Low vs high dose Peanut OIT in young subjects |

20 low dose 17 high dose |

29 months | Among younger subjects, low and high dose OIT had similar outcomes, inducing 5 g-desensitization in 81% of subjects and 1 month-SU in 78%, with good safety profile | No severe AE; no EAI. 95% of subjects had some dose-related AE, mostly mild, 15% moderate. 2 AE-related withdrawals |

| Vickery et al. 2017 | 9–36 months | 0.3 g or 3 g | ||

| Standardized peanut OIT product vs placebo, multicenter RCT | 29 OIT 26 placebo |

5–9 months | With active OIT, 79% and 62% tolerated 0.443 g and 1.043 g with minimal or no symptoms, respectively; compared to 19% and 0% on placebo (P<0.0001), with good safety profile | 93% of active and 46% of placebo groups experienced dose-related AE. Mostly mild, 4–6% moderate, none severe. 6 AE-related withdrawals, 4 due to GI symptoms |

| Bird et al. 2017 | 4–26 years | 0.3 g |

AE, adverse event; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; GI, gastrointestinal; ITT, intention to treat; OFC, oral food challenge; OIT, oral immunotherapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SU, sustained unresponsiveness.

Table 7. Wheat oral immunotherapy clinical trials.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat OIT, Open-label | 6 subjects | 6–7 months | OIT with wheat induces desensitization in most subjects (5 of 6), with acceptable safety profile | Symptoms with 6.25% of up-doses 2 urticarial reactions during maintenance |

| Rodriguez del Rio et al. 2014 | 5–11 years | 10.6 g | ||

| Wheat OIT open-label, in highly sensitized subjects | 18 active; 11 historical controls |

2 years | Among highly-sensitized subjects, wheat OIT induces 2-week SU to 5.2 g in 61%, compared to 9% of historical controls avoiding wheat | Symptoms with 6.8% of outpatient doses, with 1 EAI administration |

| Sato et al. 2015 | 5–14 years | 5.2 g |

EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; ITT, intention to treat; OIT, oral immunotherapy.

OIT with omalizumab

A major development in improving safety of OIT has been the use of omalizumab (Table 8). Its use as pretreatment and continued administration through build-up offers significant protection from IgE-mediated reactions, allowing for more rapid and safe dose escalation, with less withdrawals due to dose-related AE. However, reactions to previously tolerated doses may occur after cessation of omalizumab.44,51,52

Table 8. Oral immunotherapy with omalizumab.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk OIT with omalizumab | 11 subjects | 6 months, first 4 months with omalizumab | With concomitant administration of milk OIT and omalizumab, 82% achieve DS to 2 g 8 weeks post-omalizumab; and subsequently ingested >8 g milk protein at home. | Just 1.6% of doses elicited any reaction; After omalizumab cessation, 2 had moderate AE for which EAI given |

| Nadeau et al. 2011 | 7–17 years | 2 g | ||

| Milk OIT with or without omalizumab, RCT | 27 omalizumab 18 placebo |

28 months, all with omalizumab | While efficacy in achieving DS to 10 g and 8-wk SU were not different with and without omalizumab, AEs were significantly reduced in active group. | Omalizumab group had reduced reactions (2% vs 16%) and reduced drop-out (2 vs 5) EoE reported in placebo |

| Wood et al. 2016 | 7–32 years | 520 mg | ||

| Milk or egg OIT with omalizumab | 14 subjects, 5 cow milk allergic, 9 egg allergic |

14 months, first 2 months with omalizumab | In a group of 14 subjects unable to tolerate conventional OIT, all were able to achieve maintenance dose while on omalizumab, though some relapsed after omalizumab cessation | 60% of cow milk allergic and 33% of egg allergic developed anaphylaxis between 2.5 and 4 months after cessation of omalizumab |

| Martorell-Calatayud et al. 2016 | 3–11 years | 200 mL milk 1.8 g egg |

||

| Peanut OIT with omalizumab | 13 subjects, highly sensitized |

8 months, with omalizumab for first 2 | Even among highly sensitized, omalizumab allows for safe and effective DS, with 92% completing protocol and achieving DS to 8 g | 2 grade 3 reactions during maintenance |

| Schneider et al. 2013 | 7–15 years | 4 g | ||

| Peanut OIT, with or without omalizumab, RCT | 29 omalizumab 8 placebo |

4 months, 1st month with omalizumab | Omalizumab-treated subjects tolerated OIT at higher doses, with 79% of active achieving DS (to 2 g), vs 1 of 8 placebo. These 79% went on to demonstrate DS to 4 g 12 weeks post-omalizumab | Reactions after 7.8% active vs 16.8% placebo (P=0.15) EAI admin: Active 4, placebo 3 EoE: active 1, placebo 1 |

| MacGinnitie et al. 2017 | 6–19 years | 2 g | ||

| Multi-food OIT with omalizumab | 25 subjects | 6 months, first 4 months with omalizumab | OIT with omalizumab enabled all participants on OIT with up to 5 foods to achieve doses 10-fold higher than eliciting dose at enrollment | All moderate (at least 0.06% of doses) and severe (1 EAI admin) reactions, occurred during maintenance |

| Begin et al. 2014 | 4–15 years | 4 g per protein |

AE, adverse event; DS, desensitization; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; ITT, intention to treat; OFC, oral food challenge; OIT, oral immunotherapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SU, sustained unresponsiveness.

CM-OIT with omalizumab

In 2011, Nadeau and colleagues44 published results of a 24-week protocol with 9 weeks of omalizumab pretreatment and 16 weeks of CM-OIT with omalizumab, followed by a maintenance phase without omalizumab. In this uncontrolled pilot study, 82% of 11 enrolled subjects reached goal daily maintenance dose, demonstrated desensitization to 7.25 g of milk protein, and subsequently continued home ingestion of >8 g milk protein daily. Though all patients experienced some AE, only 1.6% of doses elicited any reaction, significantly less than 35%–50% observed in some of the first milk OIT trials.45,53 However, after cessation of omalizumab during maintenance therapy, 2 of 9 subjects administered EAI for moderate reactions after home doses.

Wood and colleagues54 published results of a 30-month CM-OIT protocol in which participants were randomized to OIT with or without omalizumab until month 28. For omalizumab and placebo groups (respectively), efficacy in achieving desensitization to 10 g CM protein OFC (89% and 71%) and 8 week-SU (48% and 36%) were similar. AEs to CM-OIT were significantly reduced in the group on omalizumab: the median percent of doses with symptoms per subject were 2.1% and 16.1%, and dose-related withdrawals were 0 and 4, respectively.

Peanut-OIT with omalizumab

Schneider and colleagues recruited highly sensitized peanut allergic subjects for open-label study of peanut-OIT with omalizumab, which was given for 12 weeks preceding OIT and continued through 2 months of OIT build-up.55 Twelve of 13 subjects reached 4 g maintenance, continued with 8 months OIT, and subsequently demonstrated desensitization to 8 g peanut protein (PP) during OFC. The most severe AEs were 2 grade 3 reactions, both of which occurred during maintenance.55 In 2016, MacGinnitie and colleagues47 conducted a study randomizing peanut-OIT subjects to omalizumab or placebo as pretreatment and during build-up phase to daily maintenance dose of 2 g. Though reaction rates were similar for omalizumab and placebo, omalizumab subjects tolerated therapy at higher doses and significantly more omalizumab subjects (79% of 29) tolerated the 4 g PP challenge 12 weeks after omalizumab cessation compared to placebo (1 of 8).

Multifood-OIT with omalizumab

Multifood-OIT addressing up to 5 foods was the subject of an open-label study, in which 25 subjects received omalizumab as pretreatment and during 8 weeks of build-up therapy to attain daily maintenance dose of 4 g food protein. All participants reached doses equivalent to a 10-fold increase in allergen tolerance by 2 months of therapy, and mean time to maintenance was just 4.5 months. Regarding safety, initial dose escalation and build-up phases were limited to mild reactions; the most severe reactions occurred during maintenance, with 0.06% of doses causing moderate chest symptoms and 0.02% moderate abdominal symptoms. One severe reaction after a home maintenance dose was treated with EAI.52

Recurrence of symptoms after cessation of omalizumab

Significant adverse reactions have been reported with continued OIT in the weeks following omalizumab cessation: Nadeau and colleagues44 reported 2 moderate AE (treated with EAI) among 11 subjects; Schneider and colleagues55 reported 2 grade 3 reactions among 13 subjects. In Begin et al.'s study with 25 subjects, all moderate reactions (with 0.06% of doses) and one severe reaction (treated with EAI) occurred during maintenance after omalizumab cessation.52

OIT with other immunomodulatory agents

OIT with probiotic

An Australian study has evaluated peanut-OIT combined with probiotic (PPOIT). Tang and colleagues56 reported that 31 PPOIT subjects, who were treated with active OIT and Lactobacillus rhamnosus CGMCC 1.3724 (NCC4007; Nestlé Health Science, Konolfingen, Switzerland) at a fixed dose of 2×1010 colony-forming units (freeze-dried powder) once daily for 18 months, had higher rates of desensitization (90% vs. 7%) and 2-5 week-SU (82% vs. 4%) compared to 28 placebo (placebo PPOIT and placebo probiotic) subjects. Regarding safety on home dosing, the PPOIT group had 6 severe AE with 3 EAI administrations compared to 4 severe AE with 2 EAI administrations on placebo. A follow-up study published in 2017 found that after a mean of 4.2 years from cessation of PPIOT, 67% of 24 PPOIT subjects were consuming peanut on a regular basis; and 58% of 12 PPOIT subjects demonstrated 8-week SU, compared to 1 of 12 placebo.43 The impact of this RCT is significantly limited by the lack of a proper control for the effect of peanut-OIT alone as well as the lack of blinding and no DBPCFC to confirm peanut allergy at baseline.

OIT with Chinese herbs

FAHF-2 is a 9-herb formula based on traditional Chinese medicine that blocks peanut-induced anaphylaxis in a murine model. In phase I studies, FAHF-2 was found to be safe and well tolerated; there was laboratory evidence of immunomodulation without appreciable clinical benefit. No significant differences in allergen-specific IgE and IgG4 levels, cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), or basophil activation between the active and placebo groups were detected. In vitro studies reported that subjects' baseline PBMCs incubated with FAHF-2 and food allergen produced significantly less IL-5, greater IL-10 levels, and increased numbers of Treg than untreated cells.57 A clinical trial is underway evaluating combination of FAHF-2, multi-food-OIT, and omalizumab (NCT 02879006).

SECTION 5: SLIT TRIALS

Overview of SLIT trials

SLIT trials have evaluated utility in treatment of hazelnut, peanut, and CM allergy (Table 9).13,31,58,59 SLIT significantly increases threshold for reactivity in subjects who comply with therapy, though with reduced efficacy compared to OIT.24,26 AE, which are typically mild and limited to oropharyngeal pruritus, are common in SLIT. Moderate and severe AE occur with less frequency in SLIT compared to OIT.13 Cofactors, as described with OIT, appear to lower threshold for reactivity to SLIT.58 Occurrence of EoE in association with aeroallergen SLIT60,61 suggests a theoretic risk for EoE with food SLIT.

Table 9. Clinical trials of sublingual immunotherapy.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazelnut SLIT vs placebo, RCT | 12 active 11 placebo |

8 to 12 weeks | Hazelnut SLIT induced desensitization in 50% of active subjects tolerating 20 g hazelnut after therapy, vs 9% placebo, with good safety profile | Mild reactions in 7.4% of doses; systemic reactions in 0.2% (N=3), all during build-up. No EAI |

| Enrique et al. 2005 | 18–60 years | 13 mg | ||

| Peanut SLIT vs placebo, RCT | 11 active 7 placebo |

12 to 18 months | Peanut SLIT induces desensitization, with active group ingesting 20-fold more protein than placebo (P=0.011), with good safety profile | Symptoms with 11.5% of active doses, vs 8.6% placebo. 1 home dose required albuterol. No EAI |

| Kim et al. 2011 | 1–11 years | 2 mg | ||

| Peanut SLIT vs placebo, RCT | 20 active 20 placebo |

11 months | Peanut SLIT induces desensitization in a majority: 70% of active tolerated 5 g or ingested 10-fold more than at baseline, vs 15% of placebo (P<0.001), with good safety profile | Symptoms with 37% of doses; 2.9% of doses require treatment, with 1 administration of albuterol and 1 EAI, during build-up |

| Fleischer et al. 2013 | 12–37 years | 165 to 1,385 μg | ||

| Peanut SLIT, long-term follow-up of Fleisher et al. 2013 | 37 active | 3 years | With 3 years peanut SLIT, only a portion (11%) of subjects achieved desensitization and 8-wk SU to 10 g, with good safety profile, but high (>50%) drop-out rate | 2% of doses with symptoms; no severe AE, no EAI. 2 AE-related withdrawals |

| Burks et al. 2015 | dose as above |

AE, adverse event; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; ITT, intention to treat; OFC, oral food challenge; OIT, oral immunotherapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy.

SLIT trials

Hazelnut-SLIT

The first SLIT trial published in 2005 reported desensitization to 20 g hazelnut (approximately 14 hazelnuts) in 50% of 12 SLIT subjects compared to 9% of 11 placebo subjects, after 8–12 weeks of therapy. Mean eliciting dose increased significantly from 2.3 to 11.6 g in SLIT subjects (P=0.02). Regarding safety, there were 3 systemic reactions, all of which occurred during build-up and responded to antihistamine. Mild reactions accompanied 7.4% of doses.58

Peanut-SLIT

Using a 12–18 month peanut-SLIT protocol enrolling subjects aged 12–37 years, Kim and colleagues13 reported that 11 active younger SLIT subjects (1–11 years) consumed 20 times more peanut than 7 subjects randomized to placebo. Compliance was similar on SLIT and placebo. Symptoms accompanied 11.5% of active and 8.6% of placebo doses; 0.26% of home SLIT doses were treated with antihistamine, 1 with albuterol; none with EAI. Using a 44-week SLIT protocol among older SLIT subjects (12–37 years), Fleischer and colleagues59 reported that 70% of 20 SLIT subjects were considered responders (ingested 5 g PP or 10-fold more than baseline), compared to 15% of 20 on placebo (P<0.001). Symptoms accompanied 37% of doses; 2.9% required treatment, with 1 administration of albuterol and 1 of EAI (during build-up). In open-label follow-up study of the same subjects, 11% of 37 subjects continuing with SLIT were desensitized to 10 g PP, with all 4 subsequently demonstrating 8-week SU. There were no EAI administrations. Twenty-five withdrew for various reasons, including 2 for dose-related AE.31

SLIT vs OIT trials

Trials compareing SLIT and OIT are presented in Table 10.

Table 10. Clinical trials comparing oral and sublingual immunotherapy.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk SLIT followed by OIT, vs milk SLIT alone, RCT | 20 SLIT/OIT 10 SLIT |

15 months | SLIT/OIT therapy was more effective than SLIT alone in inducing desensitization (70% vs 10%) and SU (40% vs 10%); though safety profile was better in SLIT. Some lost clinical desensitization 1 week off OIT | Multisystem AE and β-agonist therapy for AE were higher on SLIT/OIT than SLIT alone (IRR 11.5 and 8.6, P<0.001). 4 EAI in SLIT/OIT; 2 in SLIT alone |

| Keet et al. 2012 | 6–17 years | OIT 1 g or 2 g; SLIT 7 mg |

||

| Peanut OIT vs SLIT, RCT | 11 OIT 10 SLIT |

12 to 18 months | OIT was more effective than SLIT in inducing desensitization, with 141- vs 22-fold increase in highest tolerated dose (P=0.01), with SLIT having the better safety profile | AE more common with OIT doses (43% vs 9%, P<0.001), including moderate AE (3.4% vs 1.3%, P<0.001). 5 EAI on OIT vs 0 on SLIT |

| Narisety et al. 2015 | 7–13 years | OIT 2 g SLIT 3.7 |

AE, adverse event; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; ITT-intention to treat; OFC, oral food challenge; OIT, oral immunotherapy; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy; SU, sustained unresponsiveness.

Peanut-SLIT vs OIT

Peanut-OIT subjects experienced a 141-fold mean increase in the highest tolerated dose compared to a 22-fold mean increase among SLIT-subjects after 1 year of therapy. One-month SU was achieved by 3 of 10 OIT-subjects compared to 1 of 10 SLIT. SLIT-subjects experienced less severe AE, with 5 EAI administrations related to OIT vs none with SLIT.26

CM-SLIT vs OIT

In a study comparing CM-SLIT alone to therapy with SLIT for initial up-dosing followed by CM-OIT, SLIT/OIT subjects were significantly more likely to demonstrate desensitization (70% of 20) and 6-week SU (40% of 20) compared to subjects receiving SLIT alone (1 of 10). Multisystem reactions and medical intervention (antihistamine, albuterol, and EAI) were more frequent with OIT.24

SECTION 6: EPIT TRIALS

Overview of EPIT

Peanut and CM-EPIT have been shown to increase threshold for reactivity in 3 published trials.6 Though efficacy is more modest compared to OIT and SLIT, EPIT appears to have a more favorable side effect profile. Most AEs are limited to local cutaneous symptoms at the patch application site; occasional systemic reactions have been non-severe and resolved with antihistamine. With reduced AE and fewer visits at a medical facility for up-dosing, adherence might be better with EPIT compared to OIT and SLIT.

EPIT trials

EPIT clinical trials are summarized in Table 11. The randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1b trial of peanut-EPIT conducted in 5 centers in the US included 100 subjects, aged 6–50 years, randomized 4:1 (peanut/placebo) to receive Viaskin Peanut (VP) treatment in dosing cohorts at doses of 20, 100, 250, and 500 µg or placebo. This trial reported an overall acceptable safety and tolerability after 2 weeks of therapy. There were no severe AE and no EAI administrations; 2 systemic reactions were thought to be related to protein transfer to mucosal surface. Three of 49 active subjects withdrew due to treatment-related symptoms.7

Table 11. Clinical trials of epicutaneous immunotherapy.

| Design & reference | Sample: size & age | Protocol: duration & daily maintenance dose | Outcome (by ITT) and other significant findings | Notable adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk EPIT vs placebo, RCT | 10 active 9 placebo |

3 months of 3 48-hour applications per week, 1 mg | Milk EPIT resulted in a non-significant increase in mean maximum tolerated dose from 1.8 mL to 28 mL (P=0.18), with good safety profile | Local AE in 4 active subjects vs 2 placebo; 24 systemic AE in active group, vs 8 in placebo No anaphylaxis or EAI |

| Dupont et al. 2010 | 10 months–8 years | |||

| Peanut EPIT vs placebo, RCT | 49 active 20 placebo |

2 weeks with 4 different patch doses, 20 500 μg |

2 weeks peanut EPIT was safe and well tolerated | 2 systemic reactions; no severe AE and no EAI |

| Jones et al. 2016 | 5–50 years | |||

| Peanut EPIT vs placebo, RCT | 49 active 25 placebo |

52 weeks, 100 or 250 μg | 47% of active tolerated 5 g OFC or had 10-fold increase in successfully consumed dose, vs 15% in placebo. Treatment success more likely in <11 years | Reactions extending beyond patch site occurred in 0.1% active, one with systemic hives |

| Jones et al. 2017 | 4–25 years | |||

| Peanut EPIT vs placebo, RCT | 10 active 6 placebo |

52 weeks, 250 μg | 35.3% of active vs 13.6% of placebo demonstrated significant response. Mean cumulative reactive dose of 44 mg in active vs 144 mg placebo, with significant increase from baseline (P<0.001) | 4 treatment-related serious AE in 3 active subjects; no severe anaphylaxis. 1.1% drop-out rate due to treatment-emergent AE |

| Preliminary results released Oct 2017 | 4–11 years |

AE, adverse event; EAI, epinephrine auto-injector; EPIT, epicutaneous immunotherapy; ITT, intention to treat; OFC, oral food challenge; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SU, sustained unresponsiveness.

In the multicenter-RCT conducted by the Consortium for Food Allergy Research, 74 peanut allergic individuals (ages 4–25 years) were treated with placebo (n=25), VP 100 µg (n=24) or VP 250 µg (n=25), for 52 weeks. The primary outcome was defined as passing a 5,044-mg PP DBPCFC or achieving at least 10-fold increase in successfully consumed dose from baseline. Treatment success was seen in 3 (12%) placebo-treated participants, 11 (46%) VP100-participants, and 12 (48%) VP250-participants (P=0.005 and P=0.003, respectively, compared with placebo; VP100 vs VP250, P=0.48). Median changes in successfully consumed doses were 0, 43, and 130 mg PP in the placebo, VP100-, and VP250-groups, respectively (placebo vs VP100, P=0.014; placebo vs VP250, P=0.003). Treatment success was higher among younger children (P=0.03; age 4–11 vs >11 years). Regarding AE, 80% of EPIT doses had local reactions vs 14.4% placebo. Non-patch site reactions were reported at similar frequency in EPIT and placebo-groups (0.1% and 0.2%, respectively); no EAI or albuterol was required. There were 3 withdrawals from each group, one for treatment-related symptoms in the EPIT group.6

In October 2017, preliminary results of Peanut EPIT Efficacy and Safety (PEPITES) phase III trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of VP in children 4-11 years of age were released (https://globenewswire.com/news-release/2017/10/20/1151107/0/en/DBV-Technologies-Announces-Topline-Results-of-Phase-III-Clinical-Trial-in-Peanut-Allergic-Patients-Four-to-11-Years-of-Age.html). PEPITES reported a statistically significant response, with 35.3% of patients responding to VP 250 µg after 12-months, compared to 13.6% of placebo-patients (difference in response rates=21.7%; P<0.001; 95% confidence interval [CI], 12.4%–29.8%). The primary endpoint, defined as the 95% CI in the difference in response rates between the active and placebo arms, did not reach the 15% lower bound of the CI that was proposed in the study's Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP).

Regarding the Cumulative Reactive Dose (CRD), a key secondary endpoint measuring threshold reactivity during DBPCFC at month-12, patients treated with VP 250 µg and placebo reached a median CRD 444 mg and 144 mg PP, respectively. Median CRD at baseline was 144 mg in both groups. This increase from baseline was statistically significant compared to placebo (P<0.001). PEPITES reported 12 serious adverse events (SAEs) in 10 active-subjects (4.2%), and 6 SAEs in 6 placebo-subjects (5.1%); 4 SAEs in 3 active-subjects (1.3%) were possibly related to treatment; no SAE qualified as severe anaphylaxis. The most commonly reported AEs were mild-moderate patch application site reactions. The discontinuation rate was 10.1%, comparable between the active- and placebo-arms, with a 1.1% dropout rate due to treatment emergent AEs. Mean patient adherence exceeded 95%.

SECTION 7: CLINICAL TRIALS OF ADDITIONAL FORMS OF AIT

Other forms of AIT include SCIT with alum-adsorbed hypoallergen and LAMP-DNA vaccine, both of which are being actively investigated in human subjects. A phase IIb clinical trial evaluating safety and efficacy of SCIT with alum-adsorbed, recombinant fish allergen parvalbumin (NCT02382718) is completed but not as yet published. Preliminary results of a phase I clinical trial evaluating safety and immunomodulation with alum-adsorbed chemically modified peanut extract (NCT02851277)38 have been presented in an abstract form. Subjects were randomized to receive 15–20 incrementally increasing weekly doses of study product (HAL-MPE, n=17) or placebo (n=6). Local and systemic reactions were observed more often in the active group; no late (>4 hours after therapy) systemic reactions were observed. Authors concluded that the therapy was safe and well tolerated.38

Two additional forms of AIT, including SCIT with native peanut allergen and rectally-administered modified PP, were previously studied in humans and abandoned due to unacceptable safety profile.62,63,64

SECTION 8: AIT IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

AIT in today's clinical practice

Currently available AIT

Of various modalities of AIT, OIT is the only therapy currently accessible to physicians and patients, as food may be delivered in native form and may be purchased and/or prepared at home. While some physicians have begun offering OIT to families who are eager for therapy, OIT in the clinical setting continues to carry risks observed in research studies: in a retrospective chart review of 352 patients undergoing peanut-OIT in clinical practice, patients did experience 95 severe reactions requiring epinephrine.65

Current recommendations for OIT in clinical practice

Experts have yet to recommend that OIT be part of routine clinical practice, due to safety concerns and uncertainty regarding duration of tolerance, even following prolonged therapy. One exception to this is regular ingestion of baked goods among milk- and egg-allergic children, which appears to safely hasten tolerance acquisition to unheated milk and egg.66,67 OIT with native food proteins remains a risky endeavor; and protocols for subject selection and administration of OIT in clinical practice are lacking.

Subject-selection for OIT

When guidelines for OIT in clinical practice become available, selecting appropriate subjects for therapy will be as important as protocol design. There are currently no strict criteria to assist practitioners in choosing subjects for OIT. Patients who are highly sensitized or at high risk for severe anaphylaxis may not be appropriate candidates for OIT. Lower threshold dose at entry challenge, higher sIgE, increased sIgE: total IgE ratio, larger SPT wheal diameter, and personal history of asthma or allergic rhinitis were associated with worse outcomes, as measured by frequency of severe AE, adherence to treatment, and demonstration of desensitization and SU.12,68,69 Virtually every OIT trial excludes subjects with history of severe anaphylaxis, uncontrolled asthma, or other chronic conditions and medications which may put subjects at higher risk for more severe reactions; OIT has thus not been studied in and would not be appropriate for patients with these characteristics.

Most food-allergic patients may be of milder phenotype than those included in OIT trials: while entry OFC for clinical trials requires reactivity at doses <100–300 mg, most reactions (55%) during OFC in practice occur at doses >250 mg.70 Therefore, OFC outcomes among the majority of food-allergic subjects will be better than reported in clinical trials.

Factors unrelated to reactivity will also be important in providing safe and effective OIT. Risks of OIT may be unacceptable among patients and families who express hesitance in administering epinephrine, or who do not understand the importance of dose adjustments for and avoidance of cofactors, which lower threshold for reactivity. Compliance with therapy is likely to be hampered by anxiety surrounding dose administration, taste aversions, and insufficient resources to ensure daily dose administration and regular follow-up.

Discussion of OIT should take place in the context of a growing body of evidence on OIT as well as changing landscape of AIT for FA. With SLIT and EPIT likely to become available in the next few years, it may be that waiting for a safer option is a better strategy. Alternatively, it may become clear that immunotherapies are more effective and/or safer in younger children, and should be started sooner rather than waiting for another therapy to become available. Evidence on the safe and effective use of OIT will continue to accumulate in the coming years, with guidelines from experts likely to follow.

Selecting among AIT options in clinical practice in the future

OIT, SLIT, and EPIT for major food allergens are likely to be part of FA-management in the coming years. Depending on outcomes of other clinical trials for LAMP-DNA peanut vaccines and SCIT with hypoallergens, these too may be options. With availability of multiple options, sufficient understanding of AIT will be necessary to evaluate appropriateness of therapy for individual patients. Clinicians will need to engage patients and families in a discussion of realistic outcomes and adverse effects. This discussion will not only be guided by clinical history and allergy testing, but also by assessment of the patient's and family's goals and ability to adhere to protocols.

Combination therapy may prove to be a helpful strategy if and when multiple therapies are available. As has already been done in some clinical trials, a subject may initiate therapy with SLIT, and then transition to OIT. Sufficient desensitization with a few years of EPIT might make more effective therapies such as OIT a safer option in the future. Immunomodulatory therapies such as omalizumab, dupilumab, probiotic bacteria, and/or Chinese herbs may be combined with AIT to improve safety and efficacy.

SECTION 9: FUTURE DIRECTIONS

There is a race to develop commercial treatment for FA fueled by increasing prevalence and severity of food allergies in children, particularly peanut allergy. The multi-center phase III clinical trials of peanut-OIT and EPIT are ongoing. Approved, standardized protocols for food immunotherapy that can be safely and effectively implemented in clinical practice are needed. We also need to establish the minimum effective and safe maintenance dose, duration of AIT, and frequency of maintenance dosing for long-term therapy. Considering that at least 30% of those with persistent FA are allergic to multiple foods, treatments for milk, egg, wheat, tree nuts, seeds, fish, and shellfish allergy, as well as approaches for combining multiple foods, are desirable. Approaches to mitigating side effects of AIT, as well as mechanisms to enhance efficacy and development of permanent oral tolerance such as adjuvants, nanoparticles, DNA vaccines, or combined therapies, need to be explored. Biomarkers predictive of the favorable response to AIT are highly desirable. Patients with the most severe phenotype of life-threatening anaphylaxis are currently excluded from clinical trials, yet they are in the dire need of effective treatment that can be adhered to long-term as it is obvious that such patients will need most likely a life-long therapy. Tremendous progress has occurred in the past decade but the permanent cure for FA remains elusive and further research into tolerance development is necessary.

CONCLUSION

Emergence of FA as a global health problem underscores the importance of research to develop effective treatment strategies. A growing body of evidence supports the concept of AIT for subsets of food-allergic patients. Currently studied therapies have significant efficacy limitations and associated adverse effects, and do not offer reassurance regarding long-term protection following discontinuation of treatment. The equipoise between AIT vs food avoidance is reflected by the lack of official guidelines from the allergy societies and regulatory agencies and lack of standardized products. Hopefully within the next few years, clinicians will gain a better understanding of the utility of AIT, discover biomarkers predictive of favorable outcomes and develop strategies to enhance safety and efficacy of AIT.

Footnotes

There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nwaru BI, Hickstein L, Panesar SS, Roberts G, Muraro A, Sheikh A, et al. Prevalence of common food allergies in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2014;69:992–1007. doi: 10.1111/all.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branum AM, Lukacs SL. Food allergy among children in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1549–1555. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sicherer SH, Muñoz-Furlong A, Godbold JH, Sampson HA. US prevalence of self-reported peanut, tree nut, and sesame allergy: 11-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1322–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampson HA, Aceves S, Bock SA, James J, Jones S, Lang D, et al. Food allergy: a practice parameter update-2014. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1016–1025.e43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, Smith B, Kumar R, Pongracic J, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e9–e17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones SM, Sicherer SH, Burks AW, Leung DY, Lindblad RW, Dawson P, et al. Epicutaneous immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy in children and young adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1242–1252.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones SM, Agbotounou WK, Fleischer DM, Burks AW, Pesek RD, Harris MW, et al. Safety of epicutaneous immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy: a phase 1 study using the Viaskin patch. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1258–1261.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jongejan L, van Ree R, Poulsen LK. Hypoallergenic molecules for subcutaneous immunotherapy. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:5–7. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1103182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berin MC, Sampson HA. Mucosal immunology of food allergy. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R389–R400. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jay DC, Nadeau KC. Immune mechanisms of sublingual immunotherapy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:473. doi: 10.1007/s11882-014-0473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vickery BP, Berglund JP, Burk CM, Fine JP, Kim EH, Kim JI, et al. Early oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic preschool children is safe and highly effective. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:173–181.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim EH, Bird JA, Kulis M, Laubach S, Pons L, Shreffler W, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: clinical and immunologic evidence of desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:640–646.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumchen K, Ulbricht H, Staden U, Dobberstein K, Beschorner J, de Oliveira LC, et al. Oral peanut immunotherapy in children with peanut anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:83–91.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kemper A, Steele P, et al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Jones SM, Burks AW. Mechanisms of immune tolerance relevant to food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vickery BP, Pons L, Kulis M, Steele P, Jones SM, Burks AW. Individualized IgE-based dosing of egg oral immunotherapy and the development of tolerance. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akdis CA, Akdis M. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wambre E, DeLong JH, James EA, Torres-Chinn N, Pfützner W, Möbs C, et al. Specific immunotherapy modifies allergen-specific CD4(+) T-cell responses in an epitope-dependent manner. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:872–879.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wawrzyniak M, O'Mahony L, Akdis M. Role of regulatory cells in oral tolerance. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:107–115. doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil SU, Ogunniyi AO, Calatroni A, Tadigotla VR, Ruiter B, Ma A, et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy transiently expands circulating Ara h 2-specific B cells with a homologous repertoire in unrelated subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:125–134.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones SM, Pons L, Roberts JL, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kulis M, et al. Clinical efficacy and immune regulation with peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:292–300. 300.e1–300.e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syed A, Garcia MA, Lyu SC, Bucayu R, Kohli A, Ishida S, et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy results in increased antigen-induced regulatory T-cell function and hypomethylation of forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keet CA, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Thyagarajan A, Schroeder JT, Hamilton RG, Boden S, et al. The safety and efficacy of sublingual and oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:448–455. 455.e1–455.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vickery BP, Lin J, Kulis M, Fu Z, Steele PH, Jones SM, et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy modifies IgE and IgG4 responses to major peanut allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:128–134. 134.e1–134.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Narisety SD, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Keet CA, Gorelik M, Schroeder J, Hamilton RG, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of sublingual versus oral immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1275–1282. 1282.e1–1282.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorelik M, Narisety SD, Guerrerio Al. Chichester KL, Keet CA, Bieneman AP, et al. Suppression of the immunologic response to peanut during immunotherapy is often transient. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1283–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perezábad L, Reche M, Valbuena T, López-Fandiño R, Molina E, López-Expósito I. Oral Food desensitization in children with IgE-mediated cow's milk allergy: immunological changes underlying desensitization. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9:35–42. doi: 10.4168/aair.2017.9.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai Y, Shiraishi D, Tanaka Y, Nagasawa Y, Ohwada S, Shimauchi H, et al. Transportation of sublingual antigens across sublingual ductal epithelial cells to the ductal antigen-presenting cells in mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45:677–686. doi: 10.1111/cea.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allam JP, Würtzen PA, Reinartz M, Winter J, Vrtala S, Chen KW, et al. Phl p 5 resorption in human oral mucosa leads to dose-dependent and time-dependent allergen binding by oral mucosal Langerhans cells, attenuates their maturation, and enhances their migratory and TGF-beta1 and IL-10-producing properties. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:638–645.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burks AW, Wood RA, Jones SM, Sicherer SH, Fleischer DM, Scurlock AM, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: long-term follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1240–1248. 1248.e1–1248.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dioszeghy V, Mondoulet L, Dhelft V, Ligouis M, Puteaux E, Benhamou PH, et al. Epicutaneous immunotherapy results in rapid allergen uptake by dendritic cells through intact skin and downregulates the allergen-specific response in sensitized mice. J Immunol. 2011;186:5629–5637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]