Abstract

Drug resistance is one of the main reasons of chemotherapy failure. Therefore, overcoming drug resistance is an invaluable approach to identify novel anticancer drugs that have the potential to bypass or overcome resistance to established drugs and to substantially increase life span of cancer patients for effective chemotherapy. Oridonin is a cytotoxic diterpenoid isolated from Rabdosia rubescens with in vivo anticancer activity. In the present study, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of oridonin toward a panel of drug-resistant cancer cells overexpressing ABCB1, ABCG2, or ΔEGFR or with a knockout deletion of TP53. Interestingly, oridonin revealed lower degree of resistance than the control drug, doxorubicin. Molecular docking analyses pointed out that oridonin can interact with Akt/EGFR pathway proteins with comparable binding energies and similar docking poses as the known inhibitors. Molecular dynamics results validated the stable conformation of oridonin docking pose on Akt kinase domain. Western blot experiments clearly revealed dose-dependent downregulation of Akt and STAT3. Pharmacogenomics analyses pointed to a mRNA signature that predicted sensitivity and resistance to oridonin. In conclusion, oridonin bypasses major drug resistance mechanisms and targets Akt pathway and might be effective toward drug refractory tumors. The identification of oridonin-specific gene expressions may be useful for the development of personalized treatment approaches.

Keywords: cluster analysis, drug resistance, microarray, molecular docking, molecular dynamics, natural compound

Introduction

Chemotherapy is a mainstay of cancer treatment in addition to surgery, radiotherapy, and antibody-based immunotherapy. Conventional chemotherapy fails for many cancer patients due to various factors, drug resistance being one of the main reason together with severe side effects. Therefore, drug research constantly attempts to improve treatment results by the preclinical development of new drugs and the optimization of therapy regimens in the clinic.

Natural products always played an important role in cancer pharmacology (Newman and Cragg, 2007), they are not only well-established cytotoxic anticancer drugs (e.g., anthracyclines, Vinca alkaloids, taxanes, camptothecins, etc.), but also valuable lead compounds for the development of novel targeted chemotherapy approaches (Walkinshaw and Yang, 2008; Gallorini et al., 2012; Garcia-Carbonero et al., 2013). Natural products can exert synergistic interaction with other natural or synthetic drugs (Efferth, 2017; Nankar et al., 2017; Nankar and Doble, 2017; Wagner and Efferth, 2017; Zacchino et al., 2017a,b), they can overcome drug resistance (Guo et al., 2016; Reis et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2016; Zuo et al., 2016), reduce side effects of chemotherapy and stimulate the immune system (Lacaille-Dubois and Wagner, 2017; Schad et al., 2017).

Abnormal activation of signal transduction pathways may lead to carcinogenesis, invasion, and metastasis of tumors (Leber and Efferth, 2009; Spano et al., 2012). Signaling pathways related to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as EGFR/PI3K/AKT-mTOR pathway command a unique position in cancer biology (Efferth, 2012). Targeting those proteins led to the development of cancer therapeutics such as erlotinib and gefitinib (EGFR inhibitors), LY294002 (PI3K inhibitor), peritosine (Akt inhibitor), rapamycin and sirolimus (mTOR inhibitors), and many others.

Amplification of the EGFR gene (with a frequency of ∼50% in glioblastoma multiforme-GBM) (Furnari et al., 2007) is often associated with a tumor-specific mutation encoding a truncated form of the receptor, which lacks the extracellular binding domain, known as ΔEGFR (also named de2-7EGFR or EGFRvIII) leading to ligand-independent, constitutive tyrosine kinase activity. Expression of ΔEGFR is connected with glioma cell migration, tumor growth, invasion, survival, and resistance to treatment, and correlates with decreased overall survival in GBM patients (Heimberger et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2010). Drug resistance mediated by EGFR is not restricted to established anticancer drugs but also occurs toward other cytotoxic compounds of natural origin. Hence, EGFR-mediated resistance may represent a general type of cellular defense mechanisms toward a broad range of toxic xenobiotics (Kadioglu et al., 2015).

A well-known tumor suppressor gene, TP53 is one of the main guardian of normal cell proliferation by preventing cells with DNA damage to proliferate. Mutations or deletions in the TP53 gene are observed in approximately 50% of human cancers, leading to impaired tumor suppressor function (Wang et al., 2017). Proliferation of cells with DNA damage rises the risk of transferring mutations to the next generation upon loss of p53 functionality; therefore, deregulation of p53 often leads to tumor formation (Khoury and Domling, 2012). Abnormal p53 status is also linked with drug resistance and chemotherapy failure (Muller and Vousden, 2013).

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters play crucial role to regulate absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion in normal tissues (Natarajan et al., 2012). Overexpression of certain ABC transporters such as ABCG2/BCRP and ABCB1/Pgp in tumor cells is linked with resistance to chemotherapy. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) encoded by the ABCB1/MDR1 gene is an important mechanism of MDR and is upregulated in many clinically resistant and refractory tumors (Kuete et al., 2015a). Overexpression of P-gp is causatively linked to accelerated efflux of chemotherapeutic agents (Kadioglu et al., 2016b) such as doxorubicin, daunorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, colchicine, camptothecins, and methotrexate (Dean, 2009). For instance, P-gp-overexpressing leukemia cells involve doxorubicin resistance compared to the sensitive subline (Kadioglu et al., 2016a). BCRP is involved in the efflux of mitoxantrone, topotecan, doxorubicin, daunorubicin, irinotecan, imatinib, and methotrexate (Dean, 2009).

Oridonin is a diterpenoid isolated from Rabdosia rubescens and reveals anticancer activity in vitro and in vivo (Xiao et al., 2016; Lu et al., 2017; Yao et al., 2017), but its mode of action and effect on drug resistance have not been well studied. R. rubescens inhibited breast cancer growth and angiogenesis (Sartippour et al., 2005) and overcame drug resistance in ADR/MCF-7 breast cancer cells by increasing doxorubicin accumulation (Li et al., 2013). Therefore, it is reasonable to investigate oridonin’s mode of action on MDR in more detail.

In this study, we analyzed molecular factors determining the response of tumor cells to oridonin. Various drug resistance mechanisms were investigated. We addressed three main questions:

-

simple (1)

Is oridonin able to bypass resistance caused by different mechanisms such as P-gp, EGFR, p53, and BCRP? Moreover, can oridonin selectively target tumor cells rather than normal cells? To address these questions, we performed cytotoxicity assays.

-

simple (2)

Are there other determinants predicting sensitivity or resistance of cancer cells to oridonin? For this reason, we performed COMPARE- and hierarchical cluster analyses of transcriptome-wide mRNA expression profiles of cancer cells.

-

simple (3)

Can oridonin interact with EGFR pathway proteins? To answer this question, we applied molecular docking, MD, and Western blot.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

CCRF-CEM leukemia cells were cultured as previously described (Efferth et al., 2003b). Drug resistance of P-gp/MDR1/ABCB1-overexpressing CEM/ADR5000 cells was maintained in 5000 ng/mL doxorubicin (Kimmig et al., 1990). Breast cancer cells transduced with a control vector (MDA-MB-231-pcDNA3) or with cDNA for the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP/ABCG2 (MDA-MB-231-BCRP clone 23) were generated and maintained as reported (Doyle et al., 1998). The mRNA expression of MDR1 and BCRP in the resistant cell lines has been reported (Efferth et al., 2003a; Gillet et al., 2004). Human wild-type HCT116 colon cancer cells (p53+/+) as well as knockout clones (p53-/-) derived by homologous recombination (Bunz et al., 1998) were a generous gift from Dr. B. Vogelstein and H. Hermeking (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Baltimore, MD, United States) and cultured as described (Bunz et al., 1998).

Human GBM U87MG cells transduced with an expression vector harboring an EGFR gene with a deletion of exons 2–7 (U87MG.ΔEGFR) has been previously reported (Huang et al., 1997). Transduced and non-transduced cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. W. K. Cavenee (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, San Diego, CA, United States). Human HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells and AML12 normal hepatocytes were obtained from the American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC, United States).

Resazurin Cell Growth Inhibition Assay

The resazurin (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) reduction assay (O’Brien et al., 2000) was used to assess the cytotoxicity as previously described (Kuete et al., 2015b, 2016). Each assay was conducted at least three times, with two replicates each. Cell viability was evaluated based on a comparison with untreated cells. IC50 values were determined as concentrations required to inhibit 50% of cell proliferation and were calculated from a calibration curve by linear regression using Microsoft Excel.

Molecular Docking

The protocol for molecular docking was previously reported by us (Kadioglu et al., 2016b). An X-ray crystallography-based structure of wild-type Akt2 kinase domain (PDB ID: 3E87), EGFR (PDB ID: 1M17), mTOR (PDB ID: 4JSP), STAT3 DNA-binding domain, and VEGFR1 (PDB ID: 3HNG) were obtained from Protein Data Bank1. Homology model of STAT3 DNA-binding domain was created by us using MODELLER 9.11 (Fiser and Sali, 2003; Venkatachalam et al., 2003) and a Swiss-MODEL structure assessment tool2 based on the wild-type structure (PDB ID: 1BG1) as template. In order to assess the effect of an Akt2 mutation and EGFR mutation on oridonin binding, one point mutation-R274H on Akt2 was selected which has been shown to be critical for phosphatase resistance and keeping the phosphorylated status on Akt2 (Chan et al., 2011) and one point mutation-T790M on EGFR which has been shown to cause resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (Zhou et al., 2018). Homology model of R274H mutant Akt2 kinase domain was created in the same manner by using wild-type Akt2 kinase domain as template. T790M-mutant EGFR structure is available in PDB database (PDB ID: 5XDK). A grid box was then constructed to define docking spaces in each protein according to their pharmacophores. Docking parameters were set to 250 runs and 2,500,000 energy evaluations for each cycle. Docking was performed three times independently by Autodock4 and with AutodockTools-1.5.7rc1 (Morris et al., 2009) using the Lamarckian Algorithm. The corresponding lowest binding energies and pKi were obtained from the docking log files (dlg). Mean ± SD of binding energies were calculated from three independent docking. Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) was used to depict the docking poses of oridonin and the inhibitors for each target protein.

Molecular Dynamics

Lowest binding energy conformation of oridonin on Akt2 kinase domain prior to molecular docking analyses was picked to create ligand–protein complex structure for the MD simulations. QwikMD tool (Ribeiro et al., 2016) was used to perform 15 ns MD simulations after the equilibration of the protein–ligand complex. Stability of the docking pose was evaluated by root mean square deviation (RMSD) distance of the conformation throughout the MD simulation with the starting conformation. Total energy of the ligand–protein complex was calculated as well.

Western Blot

In order to evaluate the effect of oridonin on EGFR pathway proteins and validate the in silico results, varying concentrations of oridonin (IC50/4, IC50/2, IC50, 2xIC50, and 4xIC50), determined after the cytotoxicity test on U87MG.ΔEGFR cell line, were applied in a similar way as described previously (Saeed et al., 2015). Briefly, 1 million cells per well were seeded in 12-well plate, next day treatment with oridonin was performed, total protein were extracted after 24 h. The following primary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Frankfurt, Germany) were used: anti-rabbit EGFR, anti-rabbit phosphorylated EGFR (Tyr1068) (1:1000), anti-rabbit STAT3, anti-mouse phosphorylated STAT3 (Tyr705) (1:1000), anti-rabbit Akt, anti-rabbit phosphorylated Akt (Ser473) (1:1000), and anti-rabbit β-actin (1:2000).

COMPARE and Hierarchical Cluster Analyses

The microarray-based mRNA expression values of genes of interest and log10IC50 values for oridonin of 49 tumor cell lines were selected from the NCI database3. The COMPARE analyses were performed to produce rank-ordered lists of genes expressed in the NCI cell lines. The methodology has been previously described in detail (Wosikowski et al., 1997). Briefly, every gene of the NCI microarray database was ranked for similarity of its mRNA expression to the log10IC50 values for oridonin based on Pearson’s rank correlation test. To derive COMPARE rankings, a scale index of correlations coefficients (R-values) was created. CIM miner software was used to perform the hierarchical clustering and heat map analysis4.

Statistical Analyses

Results were represented as mean ± SD. Student’s t-test was performed in order to evaluate the statistical significance with two tails and unequal variance. Experiments with p-values lower than 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Response of Drug-Resistant Tumor Cell Lines Toward Oridonin

Cytotoxicity of oridonin and doxorubicin toward sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cell lines and normal cells were determined by the resazurin reduction assay (Table 1). The recorded IC50 values ranged from 1.65 (toward CCRF-CEM cells) to 34.68 μM (against HCT116P53-/- cells) for oridonin and from 0.24 (toward CCRF-CEM cells) to 195.12 μM (against HCT116P53-/- cells) for doxorubicin. The degree of resistance of resistant cells was calculated by dividing the IC50 value of this cell line by the IC50 value of the parental sensitive cells (Table 1). Oridonin was tested against multidrug-resistant P-gp (MDR1/ABCB1)-overexpressing CEM/ADR5000 cells and drug-sensitive parental CCRF-CEM cells using a resazurin assay. Although a weak cross-resistance of the CEM/ADR5000 cells was obtained (5.17-fold), this was much lower than that obtained with doxorubicin (975.60-fold). In another cell model for MDR, we compared the cytotoxicity of oridonin toward MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with BCRP/ABCG2 and cells transfected with pcDNA control vector. The BCRP transfectants were 1.61-fold more resistant to oridonin than their sensitive counterparts. The activities of oridonin in knockout HCT116 (p53-/-) cells and their sensitive wild-type HCT116 (p53+/+) cells were also compared. TP53-knockout cells were cross-resistant to this compound than the TP53 wild-type cells (degree of resistance: 1.92). However, the degree of resistance was slightly less resistant than that obtained with doxorubicin (2.84-fold). Interestingly, U87MG cells transfected with a deletion-activated EGFR cDNA were considerably more sensitive to oridonin than their wild-type counterpart (degree of resistance: 0.88). Normal AML10 hepatocytes were more resistant to oridonin than HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells, indicating that the cytotoxic effects of oridonin may display tumor specificity at least to some extent.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity of oridonin and doxorubicin toward sensitive and drug-resistant cancer cell lines and normal cells as determined by the resazurin reduction assay.

| Cell lines | Compounds, IC50 values in μM, and degree of resistancea (in bracket) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oridonin | Doxorubicin | Resistance mechanism | |

| CCRF-CEM | 1.65 ± 0.14 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | |

| CEM/ADR5000 | 8.53 ± 0.77 (5.17) | 195.12 ± 14.30 (975.60) | P-gp |

| MDA-MB231 | 6.06 ± 0.71 | 1.10 ± 0.01 | |

| MDA-MB231/BCRP | 9.74 ± 1.04 (1.61) | 7.83 ± 0.01 (7.11) | BCRP |

| HCT116 (p53+/+) | 18.03 ± 1.61 | 1.43 ± 0.02 | |

| HCT116 (p53-/-) | 34.68 ± 2.98 (1.92) | 4.06 ± 0.04 (2.84) | p53 |

| U87MG | 17.37 ± 1.16 | 1.06 ± 0.03 | |

| U87MG.ΔEGFR | 15.34 ± 1.67 (0.88) | 6.11 ± 0.04 (5.76) | EGFR |

| AML12 | >109.76 | >73.59 | |

| HepG2 | 25.71 ± 2.11 (<0.23) | 1.41 ± 0.12 (<0.04) | Tumor versus normal cells |

Mean values ± SD of each three independent experiments with each six parallel measurements are shown. aThe degree of resistance was determined as the ratio of IC50 value of the resistant/IC50-sensitive cell line. N.a., not applicable.

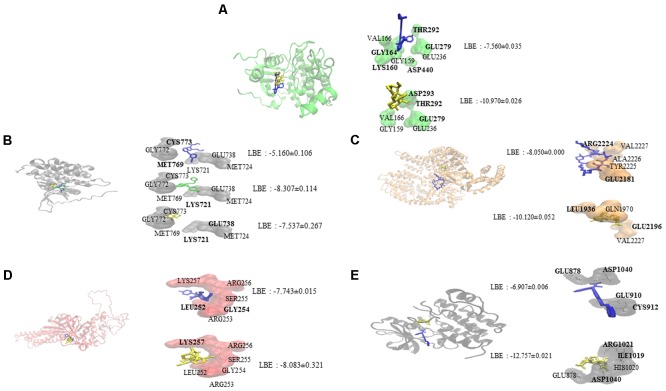

Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics

Oridonin interacts with EGFR signaling pathway proteins, as can be seen in Figure 1. Comparable binding energies and docking poses were observed for Akt2 and STAT3 proteins with those of known inhibitors [GSK690693 (Heerding et al., 2008) for Akt2 and NSC74859 (Zhang et al., 2014) for STAT3]. ATP-binding domain of Akt2 consists of the following residues: Leu158, Val166, Ala179, Val213, Met229, Tyr231, Met282, Thr292, Phe294, Ala322, and Phe439 (Huang et al., 2003). Oridonin interacts with Val166 and forms hydrogen bond with Thr292 implying its inhibitory effect.

FIGURE 1.

Molecular docking studies of oridonin and known inhibitors on proteins involved in EGFR signaling pathway. Proteins have been represented in new cartoon format with different colors, while oridonin was represented in yellow. (A) Docking poses in to the pharmacophore of Akt2 kinase domain (PDB code: 3E87 in green cartoon representation). GSK690693 was represented in blue. (B) Docking poses in to the pharmacophore of EGFR tyrosine kinase domain (PDB code: 1M17 in gray cartoon representation). Gefitinib was represented in green and erlotinib was represented in blue. (C) Docking poses in to the pharmacophore of mTOR (PDB code: 4JSP in orange representation). Sirolimus was represented in blue. (D) Docking poses in to the pharmacophore of STAT3 DNA-binding domain (homology model created by using the template PDB code: 1BG1 in pink cartoon representation). NSC74859 was represented in blue. (E) Docking poses in to the pharmacophore of VEGFR1 (PDB code: 3HNG in black cartoon representation). Axitinib was represented in blue.

Oridonin can still bind with comparable binding energies on mutant Akt2 and EGFR as can be seen in Table 2. Interestingly, oridonin interacts with EGFR-T790M significantly stronger than to wild-type EGFR (-6.633 vs. -5.160 kcal/mol). pKi is significantly lower as well (14.283 vs. 166.310 μM). Gefitinib binds to EGFR-T790M significantly weaker than to wild-type EGFR (-7.773 vs. -8.307 kcal/mol).

Table 2.

Comparison of binding energies of oridonin and known inhibitors on wild-type and mutant Akt2 and EGFR (LBE, kcal/mol; pKi, μM).

| EGFR wt |

EGFR-T790M |

LBE p-value | pKi p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBE | pKi | LBE | pKi | |||

| Oridonin | -5.160 ± 0.106 | 166.310 ± 30.323 | -6.633 ± 0.202 | 14.283 ± 5.300 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Erlotinib | -7.537 ± 0.267 | 3.183 ± 1.222 | -7.547 ± 0.371 | 3.293 ± 1.645 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| Gefitinib | -8.307 ± 0.114 | 0.820 ± 0.161 | -7.773 ± 0.196 | 2.070 ± 0.615 | <0.05 | >0.05 |

|

Akt2 wt |

Akt2-R274H |

LBE p-value | pKi p-value | |||

| LBE | pKi | LBE | pKi | |||

| Oridonin | -7.560 ± 0.035 | 2.873 ± 0.188 | -7.253 ± 0.023 | 4.830 ± 0.166 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Gsk690693 | -10.970 ± 0.026 | 0.091 ± 0.004 | -10.930 ± 0.010 | 0.097 ± 0.002 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

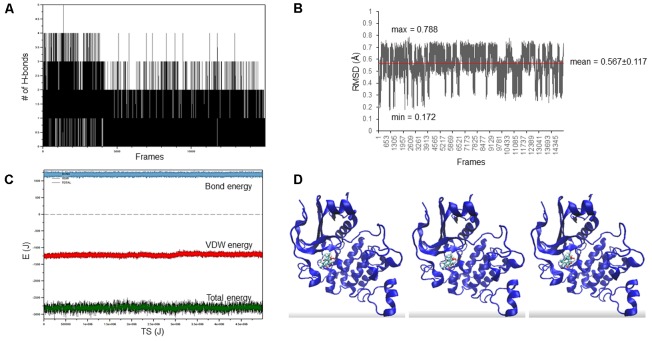

The docking pose of oridonin on Akt2 kinase domain was used as starting conformation for the MD simulation. As can be seen in Figure 2, the LBE conformation of oridonin was stable, since the RMSD value was below 1 Å (0.567 ± 0.117) throughout 15 ns simulation.

FIGURE 2.

Oridonin–Akt2 kinase domain MD simulation. (A) Number of H-bonds between oridonin and Akt2. (B) RMSD of oridonin aligned with the LBE conformation acquired after molecular docking calculations. (C) Van der Waals, total energy, bond energy of oridonin–Akt2 complex. (D) Representative screenshots from the MD simulation.

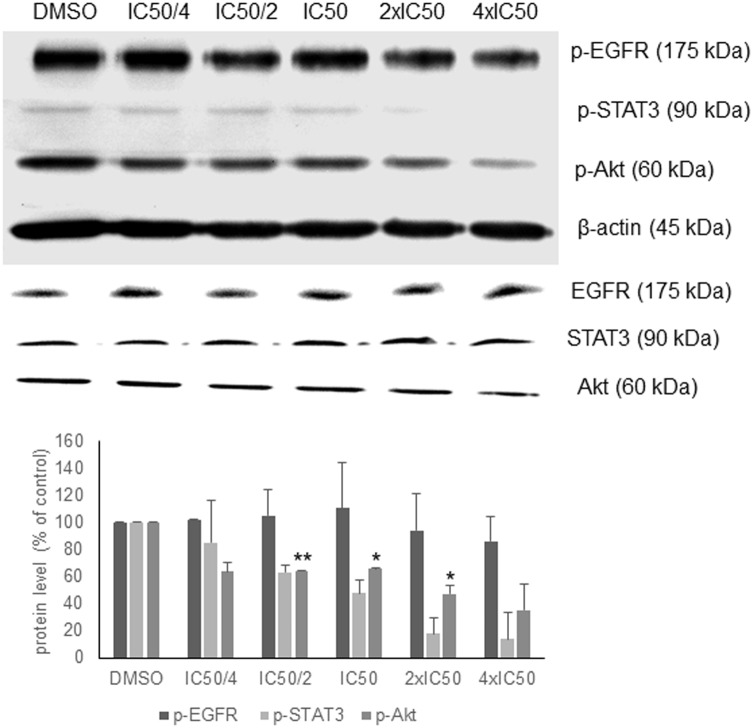

Western Blot

In order to validate the in silico analyses, the phosphorylation status of EGFR signaling proteins as parameter of their activation during signal transduction was investigated. Oridonin revealed a dose-dependent inhibition of Akt and STAT3 phosphorylation supporting the in silico analyses, but no change in EGFR phosphorylation was observed (Figure 3). There was no change at the total Akt, EGFR, and STAT3 protein levels.

FIGURE 3.

Western blot analysis of oridonin on EGFR pathway proteins. The effects of oridonin on phosphorylation of ΔEGFR, STAT3, and Akt were evaluated. Bands were normalized to β-actin in order to obtain numerical values (mean ± SEM of three independent experiments). Total EGFR, STAT3, and Akt protein levels are also shown. A representative blot is shown and statistical analysis was done by paired Student’s t-test. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗p < 0.05.

Pharmacogenomics

We investigated the transcriptome-wide RNA expression using COMPARE analysis and mined the database of the NCI by correlating the mRNA expression data with the log10IC50 values for oridonin. This is a hypothesis-generating bioinformatical approach allowing to find novel putative molecular determinants of cellular response to oridonin. The scale rankings of genes obtained by COMPARE computation were subjected to Pearson’s rank correlation tests. The thresholds for correlation coefficients were R > 0.50 for direct correlations and R < -0.50 for inverse correlations. As shown in Table 3, the identified genes can be assigned to different functional groups such as apoptosis regulation (CARD8, ANXA5), transcriptional and protein synthesis (FUBP1, RFXAP, CELF2, TWF1, COQ9), DNA repair and maintenance (RAD51C, BLM), signal transduction (PRKXP1, SRPK1, GNG12, IL6ST, PTPRK, MET), cell cycle regulation (MND1, PDS5B, PHF8), transport functions (ABCC5), cellular energy regulation (PKM2), cell adhesion (LAMB1, ADAM9), and ubiquitination (USP44).

Table 3.

Correlation of constitutive mRNA expression of genes identified by COMPARE analyses with log10IC50 values of oridonin.

| COMPARE coefficient | Experiment ID | GB accession | Gene symbol | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.717 | GC158023 | AI652861 | CELF2 | CUGBP, Elav-like family member 2 | Pre-mRNA alternative splicing, mRNA translation, and stability |

| 0.705 | GC80864 | AI983986 | PRKXP1 | Protein kinase, X-linked, pseudogene 1 | Protein kinase homologous to Drosophila DC2 kinase pseudogene 1 |

| 0.681 | GC32017 | AB020630 | PPP1R16B | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 16B | Regulator of pulmonary endothelial cell (EC) barrier function |

| 0.665 | GC186446 | NM_014959 | CARD8 | Caspase recruitment domain family, member 8 | Inhibitor of NF-κ-B activation |

| 0.664 | GC31918 | AF029670 | RAD51C | RAD51 homolog C (S. cerevisiae) | Homologous recombination (HR) DNA repair pathway |

| 0.662 | GC35837 | Z25535 | NUP153 | Nucleoporin 153 kDa | DNA-binding subunit of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) |

| 0.662 | GC78746 | AI927080 | HDHD2 | Haloacid dehalogenase-like hydrolase domain containing 2 | Hydrolase activity |

| 0.656 | GC163915 | AL036840 | FUBP1 | Far upstream element (FUSE)-binding protein 1 | Regulator of MYC expression by binding to a single-stranded far-upstream element (FUSE) upstream of the MYC promoter |

| 0.655 | GC30354 | AB023139 | KIAA0922 | KIAA0922 | Not available |

| 0.654 | GC169231 | AW249934 | PHF8 | PHD finger protein 8 | Cell cycle progression, rDNA transcription, and brain development |

| 0.653 | GC100782 | X78817 | ARHGAP4 | Rho GTPase activating protein 4 | Inhibitor of stress fiber organization |

| 0.652 | GC172537 | BC006312 | CROCCL1 | Ciliary rootlet coiled-coil, rootletin-like 1 | Not available |

| 0.652 | GC182282 | NM_003137 | SRPK1 | SRSF protein kinase 1 | Phosphorylation of SR splicing factors and regulation of splicing |

| 0.651 | GC75737 | AI815763 | ABCC5 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 5 | Multispecific organic anion pump for nucleotide analogs |

| 0.65 | GC46177 | AA542845 | MND1 | Meiotic nuclear divisions 1 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | Homologous chromosome pairing, cross-over, and intragenic recombination during meiosis |

| 0.648 | GC152371 | AF061734 | DTNBP1 | Dystrobrevin-binding protein 1 | Biogenesis of lysosome-related organelles (LRO), such as platelet dense granules and melanosomes |

| 0.647 | GC37727 | U42031 | FKBP5 | FK506-binding protein 5 | Complexation with heterooligomeric progesterone receptor, HSP90, and TEBP |

| 0.645 | GC44551 | AA448146 | USP44 | Ubiquitin-specific peptidase 44 | Deubiquitinase that prevents premature anaphase onset in the spindle assembly checkpoint |

| 0.642 | GC33552 | U39817 | BLM | Bloom syndrome, RecQ helicase-like | DNA replication and repair |

| 0.64 | GC72681 | AI742868 | RFXAP | Regulatory factor X-associated protein | Part of the RFX complex that binds to the X-box of MHC II promoters |

| -0.692 | GC18026 | AA004918 | LAMB1 | Laminin, β1 | Attachment, migration, and organization of cells into tissues during embryonic development |

| -0.667 | GC16842 | AA025336 | SPATS2L | Spermatogenesis-associated, serine-rich 2-like | Not available |

| -0.659 | GC9768 | AA047421 | GNG12 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), γ12 | Modulator or transducer in transmembrane signaling systems |

| -0.645 | GC18754 | AA036724 | CAV2 | Caveolin 2 | Regulation of G-protein α-subunits |

| -0.642 | GC10289 | AA053017 | ANXA5 | Annexin A5 | Bloodvanticoagulant protein that inhibits the thromboplastin-specific complex |

| -0.64 | GC9921 | AA045041 | TWF1 | Twinfilin, actin-binding protein, homolog 1 (Drosophila) | Inhibitor of actin polymerization likely by sequestering G-actin |

| -0.623 | GC18611 | AA034024 | RAI14 | Retinoic acid induced 14 | Not available |

| -0.617 | GC15762 | W47533 | ADAM9 | ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 | Cell–cell or cell–matrix interactions |

| -0.615 | GC13860 | H85457 | IL6ST | Interleukin 6 signal transducer (gp130, oncostatin M receptor) | Signal-transducing molecule |

| -0.613 | GC10564 | T72607 | PDS5B | PDS5, regulator of cohesion maintenance, homolog B (S. cerevisiae) | Regulator of sister chromatid cohesion in mitosis which stabilizes cohesin complex association with chromatin |

| -0.612 | GC18739 | AA035170 | TICAM2 | Toll-like receptor adaptor molecule 2 | Regulator of the MYD88-independent pathway during the innate immune response to LPS |

| -0.607 | GC9920 | AA045034 | OSTM1 | Osteopetrosis-associated transmembrane protein 1 | Osteoclast and melanocyte maturation and function |

| -0.605 | GC174276 | BE908217 | ANXA2 | Annexin A2 | Calcium-regulated membrane-binding protein |

| -0.599 | GC180243 | NM_000445 | PLEC | Plectin | Linker of intermediate filaments with microtubules and microfilaments and anchor of intermediate filaments to desmosomes or hemidesmosomes |

| -0.599 | GC33491 | L77886 | PTPRK | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, K | Negative regulator of EGFR signaling pathway |

| -0.597 | GC89723 | M26252 | PKM2 | Pyruvate kinase, muscle | Transfer of a phosphoryl group from phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to ADP to generate ATP |

| -0.59 | GC13104 | R97218 | MET | Met proto-oncogene (hepatocyte growth factor receptor) | Signal transducer from the extracellular matrix into the cytoplasm |

| -0.585 | GC187142 | NM_016639 | TNFRSF12A | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12A | Angiogenesis and proliferation of endothelial cells |

| -0.584 | GC14757 | N62737 | MFAP3L | Microfibrillar-associated protein 3-like | Not available |

| -0.581 | GC18658 | AA034910 | COQ9 | Coenzyme Q9 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | Biosynthesis of coenzyme Q |

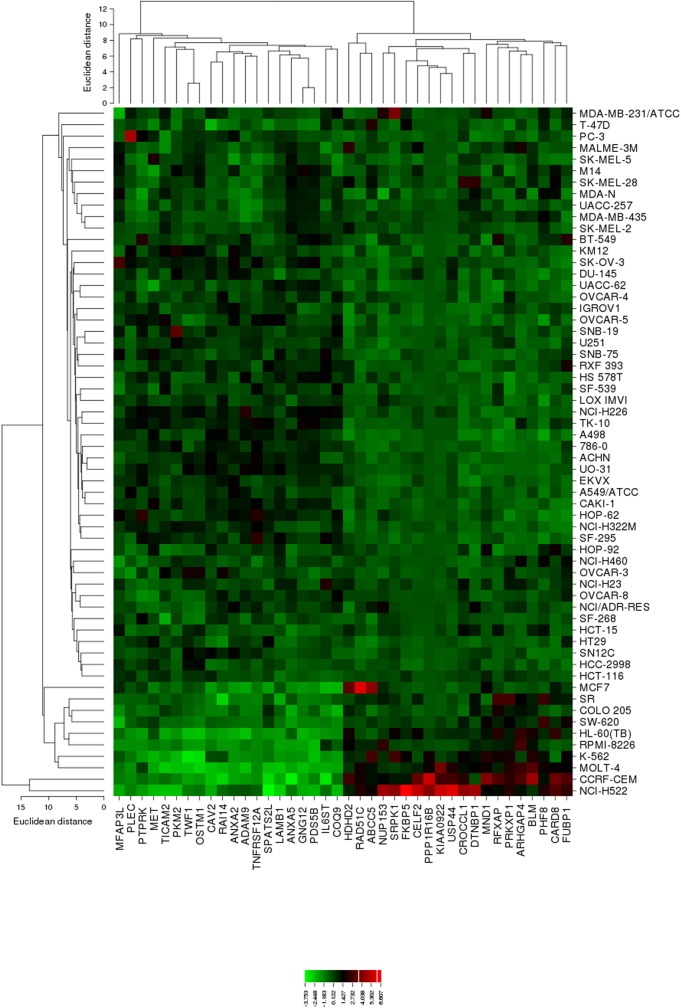

The mRNA expression values of all NCI cell lines for the genes listed in Table 3 were subsequently subjected to agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis, in order to find out, whether clusters of cell lines could be identified with similar behavior after exposure to oridonin. The dendrogram of the cluster analysis showed three clusters (Figure 4). As a next step, the log10IC50 values for oridonin, which were not included in the cluster analysis, were assigned to the corresponding position of the cell lines in the cluster tree. The distribution among the clusters was significantly different from each other as determined by Chi-square test (p-value = 0.0014). Cluster 1 contained in its majority of cell lines resistant to oridonin, whereas Cluster 3 contained in its majority sensitive ones (Cluster 1: 17 resistant and 7 sensitive; Cluster 2: 8 resistant and 8 sensitive; Cluster 3: 0 resistant and 9 sensitive).

FIGURE 4.

Heat map obtained by hierarchical cluster analysis from microarray-based mRNA expression profiles of the genes shown in Table 3 correlating with cellular responsiveness to oridonin. The analysis shows the clustering of 49 NCI tumor cell lines.

Discussion

Oridonin is a diterpenoid isolated from R. rubescens with previously reported anticancer activity. It targets PI3K/Akt pathway causing G2/M arrest in prostate cancer cells (Lu et al., 2017). Oridonin also targets Notch signaling leading to inhibition of breast cancer progression (Xia et al., 2017). According to the literature, 4 μg/mL or 10 μM is the upper IC50 limit considered for a promising cytotoxic compound after incubation for 48 and 72 h (Boik, 2001; Brahemi et al., 2010; Kuete and Efferth, 2015). In the present work, oridonin displayed IC50 values (<10 μM) within this threshold value toward four tested cancer cell lines as determined by resazurin assay. These data show the antiproliferative potential of oridonin against drug-sensitive and -resistant cancer cell lines since identification of compounds able to overcome MDR is an attractive strategy in drug research (Efferth, 2001; Gottesman and Ling, 2006; Gillet et al., 2007). Interestingly, the resistant U87MG.ΔEGFR cells were even more sensitive to oridonin than their corresponding sensitive counterparts (U87MG cells). If cross-resistance was obtained, the degree or resistance was lower in all cases than that of the reference compound, doxorubicin. This suggests that oridonin could be explored further to develop a cytototoxic drug to combat MDR phenotypes.

Overexpression of P-gp, a broad spectrum drug transporter, leads to the efficient extrusion of a large number of established anticancer drugs and cytotoxic natural products out of cancer cells. This is the main reason, why tumors with P-gp overexpression exert a MDR phenotype limiting the success of established drugs. Therefore, it was a pleasing result that the expression of P-gp/MDR1 in the NCI cell line panel did not correlate with cellular response to oridonin, which implies that P-gp does not confer resistance to oridonin. In addition, multidrug-resistant CEM/ADR5000 cells with overexpression of various ABC transporters including P-gp/MDR1 (400-fold) (Kadioglu et al., 2016a) revealing high degrees of resistance to well-known anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin (1036-fold), vincristine (613-fold), docetaxel (435-fold), and many others (Efferth et al., 2008) were even slightly more sensitive to oridonin than the parental, wild-type, drug-sensitive CCRF-CEM tumor cells. It can be speculated that oridonin successfully kills otherwise unresponsive, multidrug-resistant tumors.

Oridonin revealed comparable binding energies to EGFR pathway proteins as the known inhibitors. It shares the same docking pose with GSK690693 on Akt2 and NSC74859 on STAT3, implying the inhibitory potential of oridonin toward Akt2 and STAT3. MD study revealed that oridonin docking pose on Akt2 is stable throughout the simulation with a relatively small RMSD deviation (<1 Angström). In order to validate the in silico findings and further evaluate the mode of action of oridonin, western blot experiments for the EGFR pathway proteins regarding their phosphorylation status upon oridonin treatment were performed. Results implied that cytotoxicity of oridonin is dependent on the EGFR pathway influence.

Various other resistance factors in addition to EGFR and P-gp determine the success rate of chemotherapy. In order to achieve a deeper understanding of drug response determinant mechanisms, microarray technology is widely used. This methodology is especially helpful to identify potential mechanisms of novel, still incompletely understood cytotoxic compounds. For this purpose, we performed COMPARE and hierarchical cluster analyses of transcriptome-wide, microarray-based mRNA expression of the NCI cell line panel. The expression of the genes identified via COMPARE analyses determined cellular response to oridonin in this panel of cell lines.

Despite P-gp expression was not correlated to oridonin resistance, our COMPARE analysis revealed that another member of ABC superfamily, i.e., ABCC5, was a molecular determinant to mediate resistance to oridonin in the NCI cancer cell line panel. In this context, it is worth to mention that a member of the ABC sub-family C, ABCC1 (multidrug protein 1, MRP1), which is known to confer MDR phenotype differs from that one caused by P-gp (ABCB1/MDR1) and BCRP/ABCG2 (Efferth, 2001).

In conclusion, oridonin targeted various resistance mechanisms and inhibited Akt2 and STAT3 phosphorylation. The resistance and sensitivity genes identified may be helpful for the development of personalized therapy approaches, as their expression in an individual patient may suggest potentially successful oridonin treatment in the future. However, further preclinical and clinical studies are required to assess the therapeutic potential of oridonin for cancer therapy.

Author Contributions

TE conceived the study. OK performed the in silico experiments. MS contributed to the in silico experiments. OK, MS, HG, and TE wrote the manuscript. OK, MS, and VK performed the in vitro experiments. All the authors read the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

OK was funded by intramural funds at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Mainz, Germany. VK was very grateful to the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for the funding through the Institutional Village Linkage Program (2015–2018).

ABBREVIATIONS

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- LBE

lowest binding energy

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- MD

molecular dynamics

- pKi

predicted inhibition constant.

Footnotes

References

- Boik J. (2001). Natural Compounds in Cancer Therapy. Princeton, MN: Oregon Medical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brahemi G., Kona F. R., Fiasella A., Buac D., Soukupova J., Brancale A., et al. (2010). Exploring the structural requirements for inhibition of the ubiquitin E3 ligase breast cancer associated protein 2 (BCA2) as a treatment for breast cancer. J. Med. Chem. 53 2757–2765. 10.1021/jm901757t [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunz F., Dutriaux A., Lengauer C., Waldman T., Zhou S., Brown J. P., et al. (1998). Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science 282 1497–1501. 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan T. O., Zhang J., Rodeck U., Pascal J. M., Armen R. S., Spring M., et al. (2011). Resistance of Akt kinases to dephosphorylation through ATP-dependent conformational plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 E1120–E1127. 10.1073/pnas.1109879108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M. (2009). ABC transporters, drug resistance, and cancer stem cells. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 14 3–9. 10.1007/s10911-009-9109-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L. A., Yang W., Abruzzo L. V., Krogmann T., Gao Y., Rishi A. K., et al. (1998). A multidrug resistance transporter from human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 15665–15670. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T. (2001). The human ATP-binding cassette transporter genes: from the bench to the bedside. Curr. Mol. Med. 1 45–65. 10.2174/1566524013364194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T. (2012). Signal transduction pathways of the epidermal growth factor receptor in colorectal cancer and their inhibition by small molecules. Curr. Med. Chem. 19 5735–5744. 10.2174/092986712803988884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T. (2017). Cancer combination therapy of the sesquiterpenoid artesunate and the selective EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib. Phytomedicine 37 58–61. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T., Gebhart E., Ross D. D., Sauerbrey A. (2003a). Identification of gene expression profiles predicting tumor cell response to L-alanosine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T., Konkimalla V. B., Wang Y. F., Sauerbrey A., Meinhardt S., Zintl F., et al. (2008). Prediction of broad spectrum resistance of tumors towards anticancer drugs. Clin. Cancer Res. 14 2405–2412. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T., Sauerbrey A., Olbrich A., Gebhart E., Rauch P., Weber H. O., et al. (2003b). Molecular modes of action of artesunate in tumor cell lines. Mol. Pharmacol. 64 382–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiser A., Sali A. (2003). Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol. 374 461–491. 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari F. B., Fenton T., Bachoo R. M., Mukasa A., Stommel J. M., Stegh A., et al. (2007). Malignant astrocytic glioma: genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev. 21 2683–2710. 10.1101/gad.1596707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallorini M., Cataldi A., Di Giacomo V. (2012). Cyclin-dependent kinase modulators and cancer therapy. BioDrugs 26 377–391. 10.2165/11634060-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carbonero R., Carnero A., Paz-Ares L. (2013). Inhibition of HSP90 molecular chaperones: moving into the clinic. Lancet Oncol. 14 e358–e369. 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70169-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet J., Efferth T., Steinbach D., Hamels J., De Longueville F., Bertholet V., et al. (2004). Microarray-based detection of multidrug resistance in human tumor cells by expression profiling of ATP-binding cassette transporter genes. Cancer Res. 64 8987–8993. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillet J. P., Efferth T., Remacle J. (2007). Chemotherapy-induced resistance by ATP-binding cassette transporter genes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1775 237–262. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman M. M., Ling V. (2006). The molecular basis of multidrug resistance in cancer: the early years of P-glycoprotein research. FEBS Lett. 580 998–1009. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Ding Y. Y., Zhang T., An H. L. (2016). Sinapine reverses multi-drug resistance in MCF-7/dox cancer cells by downregulating FGFR4/FRS2 alpha-ERK1/2 pathway-mediated NF-kappa B activation. Phytomedicine 23 267–273. 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerding D. A., Rhodes N., Leber J. D., Clark T. J., Keenan R. M., Lafrance L. V., et al. (2008). Identification of 4-(2-(4-amino-125-oxadiazol-3-yl)-1-ethyl-7-{[(3S)-3-piperidinylmethyl]oxy}-1H- imidazo[45-c]pyridin-4-yl)-2-methyl-3-butyn-2-ol (GSK690693), a novel inhibitor of AKT kinase. J. Med. Chem. 51 5663–5679. 10.1021/jm8004527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberger A. B., Hlatky R., Suki D., Yang D., Weinberg J., Gilbelbrt M., et al. (2005). Prognostic effect of epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma multiforme patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 11 1462–1466. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. S., Nagane M., Klingbeil C. K., Lin H., Nishikawa R., Ji X. D., et al. (1997). The enhanced tumorigenic activity of a mutant epidermal growth factor receptor common in human cancers is mediated by threshold levels of constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation and unattenuated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 272 2927–2935. 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Begley M., Morgenstern K. A., Gu Y., Rose P., Zhao H., et al. (2003). Crystal structure of an inactive Akt2 kinase domain. Structure 11 21–30. 10.1016/S0969-2126(02)00937-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadioglu O., Cao J., Kosyakova N., Mrasek K., Liehr T., Efferth T. (2016a). Genomic and transcriptomic profiling of resistant CEM/ADR-5000 and sensitive CCRF-CEM leukaemia cells for unravelling the full complexity of multi-factorial multidrug resistance. Sci. Rep. 6:36754. 10.1038/srep36754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadioglu O., Cao J., Saeed M. E., Greten H. J., Efferth T. (2015). Targeting epidermal growth factor receptors and downstream signaling pathways in cancer by phytochemicals. Target Oncol. 10 337–353. 10.1007/s11523-014-0339-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadioglu O., Saeed M. E. M., Valoti M., Frosini M., Sgaragli G., Efferth T. (2016b). Interactions of human P-glycoprotein transport substrates and inhibitors at the drug binding domain: Functional and molecular docking analyses. Biochem. Pharmacol. 104 42–51. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury K., Domling A. (2012). P53 mdm2 inhibitors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 18 4668–4678. 10.2174/138161212802651580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmig A., Gekeler V., Neumann M., Frese G., Handgretinger R., Kardos G., et al. (1990). Susceptibility of multidrug-resistant human leukemia cell lines to human interleukin 2-activated killer cells. Cancer Res. 50 6793–6799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuete V., Efferth T. (2015). African flora has the potential to fight multidrug resistance of cancer. Biomed Res. Int. 2015:914813. 10.1155/2015/914813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuete V., Fouotsa H., Mbaveng A. T., Wiench B., Nkengfack A. E., Efferth T. (2015a). Cytotoxicity of a naturally occurring furoquinoline alkaloid and four acridone alkaloids towards multi-factorial drug-resistant cancer cells. Phytomedicine 22 946–951. 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuete V., Mbaveng A. T., Nono E. C., Simo C. C., Zeino M., Nkengfack A. E., et al. (2016). Cytotoxicity of seven naturally occurring phenolic compounds towards multi-factorial drug-resistant cancer cells. Phytomedicine 23 856–863. 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuete V., Sandjo L. P., Mbaveng A. T., Zeino M., Efferth T. (2015b). Cytotoxicity of compounds from Xylopia aethiopica towards multi-factorial drug-resistant cancer cells. Phytomedicine 22 1247–1254. 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacaille-Dubois M. A., Wagner H. (2017). New perspectives for natural triterpene glycosides as potential adjuvants. Phytomedicine 37 49–57. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leber M. F., Efferth T. (2009). Molecular principles of cancer invasion and metastasis (review). Int. J. Oncol. 34 881–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Fan J., Wu Z., Liu R. Y., Guo L., Dong Z., et al. (2013). Reversal effects of Rabdosia rubescens extract on multidrug resistance of MCF-7/Adr cells in vitro. Pharm. Biol. 51 1196–1203. 10.3109/13880209.2013.784342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M. Z., Yang Y., Wang C., Sun L. D., Mei C. Z., Yao W. T., et al. (2010). The effect of epidermal growth factor receptor variant III on glioma cell migration by stimulating ERK phosphorylation through the focal adhesion kinase signaling pathway. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 502 89–95. 10.1016/j.abb.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Chen X., Qu S., Yao B., Xu Y., Wu J., et al. (2017). Oridonin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in hormone-independent prostate cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 13 2838–2846. 10.3892/ol.2017.5751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris G. M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M. F., Belew R. K., Goodsell D. S., et al. (2009). AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30 2785–2791. 10.1002/jcc.21256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P. A., Vousden K. H. (2013). p53 mutations in cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 15 2–8. 10.1038/ncb2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nankar R., Prabhakar P. K., Doble M. (2017). Hybrid drug combination: combination of ferulic acid and metformin as anti-diabetic therapy. Phytomedicine 37 10–13. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nankar R. P., Doble M. (2017). Hybrid drug combination: anti-diabetic treatment of type 2 diabetic Wistar rats with combination of ellagic acid and pioglitazone. Phytomedicine 37 4–9. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K., Xie Y., Baer M. R., Ross D. D. (2012). Role of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in cancer drug resistance. Biochem. Pharmacol. 83 1084–1103. 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. J., Cragg G. M. (2007). Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J. Nat. Prod. 70 461–477. 10.1021/np068054v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien J., Wilson I., Orton T., Pognan F. (2000). Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Biochem. 267 5421–5426. 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis M. A., Ahmed O. B., Spengler G., Molnar J., Lage H., Ferreira M. J. U. (2016). Jatrophane diterpenes and cancer multidrug resistance-ABCB1 efflux modulation and selective cell death induction. Phytomedicine 23 968–978. 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro J. V., Bernardi R. C., Rudack T., Stone J. E., Phillips J. C., Freddolino P. L., et al. (2016). QwikMD - Integrative molecular dynamics toolkit for novices and experts. Sci. Rep. 6:26536. 10.1038/srep26536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed M., Jacob S., Sandjo L. P., Sugimoto Y., Khalid H. E., Opatz T., et al. (2015). Cytotoxicity of the sesquiterpene lactones neoambrosin and damsin from Ambrosia maritima against multidrug-resistant cancer cells. Front. Pharmacol. 6:267. 10.3389/fphar.2015.00267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartippour M. R., Seeram N. P., Heber D., Hardy M., Norris A., Lu Q., et al. (2005). Rabdosia rubescens inhibits breast cancer growth and angiogenesis. Int. J. Oncol. 26 121–127. 10.3892/ijo.26.1.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad F., Thronicke A., Merkle A., Matthes H., Steele M. L. (2017). Immune-related and adverse drug reactions to low versus high initial doses of Viscum album L. in cancer patients. Phytomedicine 36 54–58. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spano D., Heck C., De Antonellis P., Christofori G., Zollo M. (2012). Molecular networks that regulate cancer metastasis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 22 234–249. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng Y. N., Sheu M. J., Hsieh Y. W., Wang R. Y., Chiang Y. C., Hung C. C. (2016). beta-carotene reverses multidrug resistant cancer cells by selectively modulating human P-glycoprotein function. Phytomedicine 23 316–323. 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam T. K., Qazi S., Samuel P., Uckun F. M. (2003). Inhibition of mast cell leukotriene release by thiourea derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13 485–488. 10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00992-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H., Efferth T. (2017). Introduction: Novel hybrid combinations containing synthetic or antibiotic drugs with plant-derived phenolic or terpenoid compounds. Phytomedicine 37 1–3. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkinshaw D. R., Yang X. J. (2008). Histone deacetylase inhibitors as novel anticancer therapeutics. Curr. Oncol. 15 237–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zhao Y., Aguilar A., Bernard D., Yang C. Y. (2017). Targeting the MDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction for new cancer therapy: progress and challenges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 7:a026245. 10.1101/cshperspect.a026245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wosikowski K., Schuurhuis D., Johnson K., Paull K. D., Myers T. G., Weinstein J. N., et al. (1997). Identification of epidermal growth factor receptor and c-erbB2 pathway inhibitors by correlation with gene expression patterns. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 89 1505–1515. 10.1093/jnci/89.20.1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S., Zhang X., Li C., Guan H. (2017). Oridonin inhibits breast cancer growth and metastasis through blocking the Notch signaling. Saudi Pharm. J. 25 638–643. 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., He Z., Cao W., Cai F., Zhang L., Huang Q., et al. (2016). Oridonin inhibits gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cells by suppressing EGFR/ERK/MMP-12 and CIP2A/Akt signaling pathways. Int. J. Oncol. 48 2608–2618. 10.3892/ijo.2016.3488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z., Xie F., Li M., Liang Z., Xu W., Yang J., et al. (2017). Oridonin induces autophagy via inhibition of glucose metabolism in p53-mutated colorectal cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 8:e2633. 10.1038/cddis.2017.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchino S. A., Butassi E., Cordisco E., Svetaz L. A. (2017a). Hybrid combinations containing natural products and antimicrobial drugs that interfere with bacterial and fungal biofilms. Phytomedicine 37 14–26. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchino S. A., Butassi E., Di Liberto M., Raimondi M., Postigo A., Sortino M. (2017b). Plant phenolics and terpenoids as adjuvants of antibacterial and antifungal drugs. Phytomedicine 37 27–48. 10.1016/j.phymed.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Yang X., Zhang Q., Guo Q., He J., Qin Q., et al. (2014). STAT3 inhibitor NSC74859 radiosensitizes esophageal cancer via the downregulation of HIF-1alpha. Tumour Biol. 35 9793–9799. 10.1007/s13277-014-2207-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Hu Q., Zhang X., Zheng J., Xie B., Xu Z., et al. (2018). Sensitivity to chemotherapeutics of NSCLC cells with acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs is mediated by T790M mutation or epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncol. Rep. 39 1783–1792. 10.3892/or.2018.6242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo G. Y., Wang C. J., Han J., Li Y. Q., Wang G. C. (2016). Synergism of coumarins from the Chinese drug Zanthoxylum nitidum with antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Phytomedicine 23 1814–1820. 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]