Abstract

Receptor-targeting radiolabeled molecular probes with high affinity and specificity are useful in studying and monitoring biological processes and responses. Dual- or multiple-targeting probes, using radiolabeled metal chelates conjugated to peptides, have potential advantages over single-targeting probes as they can recognize multiple targets leading to better sensitivity for imaging and radiotherapy when target heterogeneity is present. Two natural hormone peptide receptors, gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) and Y1, are specifically interesting as their expression is upregulated in most breast and prostate cancers. One of our goals has been to develop a dual-target probe that can bind both GRP and Y1 receptors. Consequently, a heterobivalent dual-target probe, t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A (where a GRP targeting ligand J-G-Abz4-QWAVGHLM-NH2 and Y1 targeting ligand INP-K [ɛ-J-(α-DO3A-ɛ-DGa)-K] YRLRY-NH2 were coupled), that recognizes both GRP and Y1 receptors was synthesized, purified, and characterized in the past. Competitive displacement cell binding assay studies with the probe demonstrated strong affinity (IC50 values given in parentheses) for GRP receptors in T-47D cells (18 ± 0.7 nM) and for Y1 receptors in MCF7 cells (80 ± 11 nM). As a further evaluation of the heterobivalent dual-target probe t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A, the objective of this study was to determine its mouse and human serum stability at 37°C. The in vitro metabolic degradation of the dual-target probe in mouse and human serum was studied by using a 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A and a high-performance liquid chromatography/radioisotope detector analytical method. The half-life (t1/2) of degradation of the dual-target probe in mouse serum was calculated as 7 hours and only ∼20% degradation was seen after 6 hours incubation in human serum. The slow in vitro metabolic degradation of the dual-target probe can be compared with the degradation t1/2 of the corresponding monomeric probes, BVD15-DO3A and AMBA: 15, and ∼40 minutes for BVD15-DO3A and 3.1 and 38.8 hours for AMBA in mouse and human serum, respectively. A possible pathway for in vitro metabolic degradation of the t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A in mouse serum is proposed based on the chromatographic retention times of the intact probe and its degradants.

Keywords: : dual-target probe, GRP receptor, heterobivalent, human serum stability, mouse serum stability, NPY receptor, radiolabeling, radiotracers

Introduction

Breast cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the Western World, consequently, improved novel approaches for detection of primary and metastatic breast cancers followed by treatment are urgently needed to increase the survival rate of patients, especially in later stage of disease.1,2 Breast cancer can express different types of peptide receptors, for example, somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), and neuropeptide Y (NPY) receptors.3–5 In addition, GRP receptors are overexpressed in several other types of human cancers also, including prostate, lung, colon, gastric, and pancreas, and it regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and morphology. Apart from breast cancer, the NPY1 receptors are also present in prostate cancer cells, ovarian tumors, renal cell carcinoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.6–8

Radiolabeled fluoro-deoxy-glucose (18fluorine-FDG) has primarily been used for positron emission tomography imaging of hypermetabolic tumors; however, it has some limitations in the diagnosis of most cancers.9 Consequently, the need for receptor-targeted imaging agents has led to the development of numerous radiolabeled peptides that can target specific peptide receptors that are known to overexpress in tumor cells.10–14

Two peptides with specific amino acid sequence, Bombesin (BBN), an amphibian 14-amino acid analogue of the 27 amino acid mammalian regulatory GRP, and a NPY, a 36 amino acid peptide amide of pancreatic polypeptide family, have shown strong affinity for neuromedin and BB2 subtypes of GRP and for Y1, Y2, and Y3 subtype receptors, respectively. Various analogues of these two peptides have been evaluated as potential imaging/therapeutic agents. This involves conjugating a peptide to a chelating agent (essential for carrying a radionuclide) through a spacer, radiolabeling of the conjugate by an appropriate radionuclide, followed by in vitro/in vivo testing of the radiolabeled molecular probe.10–28

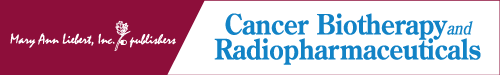

For example, a bombesin-like agonist peptide (AMBA = DO3A-CH2CO-G-[4-aminobenzyl]-QWAVGHLM-NH2, Structure I in Fig. 1) was synthesized, labeled with 177Lu, and showed high affinity toward the GRP receptor in a PC-3 cell line (measured IC50 values were 4.75 ± 0.25 and 2.5 ± 0.5 nM for AMBA and Lu(AMBA), respectively).22 Mouse and human serum stability half-lives (t1/2) of 177Lu-labeled AMBA were 3.1 and 38.8 hours, respectively.22177Lu-labeled AMBA demonstrated therapeutic efficacy in a PC-3 human prostate tumor-bearing mouse model in preclinical studies.22,23 Similarly, a truncated NPY analogue (BVD15 = Pro-Tyr-Leu-NPY(28-26)NH2, Structure II Fig. 1) conjugated with DO3A (i.e., [Lys(DOTA)]BVD1527 or hereafter to be named as BVD15-DO3A)34 showed strong affinity toward Y1 receptors, in human breast carcinoma (MCF-7) cell lines, with an IC50 value of 63 ± 25 nM. However, the information related to mouse and human serum stability of Lys(DOTA)]BVD1527 or BVD15-DO3A is lacking.27

FIG. 1.

Structure of AMBA, BVD15-DO3A, and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A.

Relatively low tumor affinity, short retention times, and heterogeneity of receptor expression have been issues with the peptide-based molecular probes. To overcome these issues, multivalency approaches involving peptide homodimers and heterodimers have emerged recently.29–35 These dimers are capable of targeting either two different domains of one receptor or two different receptors simultaneously.

Reubi recently determined that both GRPr and Y1 receptors were present in many breast cancer tissue samples and, importantly, that they were expressed in a complementary way.3 Consequently, in a recent report35 we described the design and development of a novel heterobivalent peptide ligand, t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A (Structure III, Fig. 1), that consists of a GRP targeting ligand J-G-Abz4-QWAVGHLM-NH2 and a Y1 targeting ligand INP-K[ɛ-J-(α-DO3A-ɛ-DGa)-K]YRLRY-NH2. The dual-target probe showed strong affinity toward GRP and Y1 receptors in competitive displacement cell binding assays. For example, the measured IC50 values of the dual-target probe were 18 ± 0.7 and 80 ± 11 nM against 125I-Tyr4-BBN for GRPR in T-47D cells and against 125I-NPY for Y1 receptors in MCF7 cells (both cells from human breast cancer cell lines), respectively. These values were found to be comparable with the IC50 values of the respective monomeric components AMBA (4.75 ± 0.25 nM)22 in T47D cells and BVD15-DO3A (63 ± 25 nM)27 in MCF7 cells, demonstrating that the dual-target probe is capable of targeting the two receptors successfully.

For characterization, development, and translation of a novel molecular probe into the clinic, it must be evaluated in a series of tests, including in vitro cell binding assays, serum stability studies, biodistribution of the radiolabeled material, and finally imaging studies in preclinical animal models. Consequently, the objective of this study was to determine the in vitro mouse and human serum stability of BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A at 37°C and to compare their stability with the mouse and human serum stability of AMBA.

153Gd radionuclide (with 241.6 days t1/2 and 79, 97, and 103 kV gamma peaks) was used as a radio tracer for monitoring degradation of BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A in mouse and human serum rather than a radionuclide with shorter t1/2 (177Lu with t1/2 of 6.7 days). A single lot of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A could be used for all experiments, because of longer t1/2 of 153Gd, in these studies, resulting in less variability from one lot to another of the radiolabeled material. We report herein that in vitro metabolic degradation of the dual-target probe, t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A, in mouse and human serum is significantly slower than corresponding monomeric probes AMBA and BVD15-DO3A. A possible pathway for in vitro metabolic degradation of t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A in mouse serum is proposed based on the chromatographic retention times of the intact probe and its degradants.

Experimental Section: Materials and Methods

A Y1 targeting ligand and a heterobivalent dual-target probe conjugated with a DO3A chelating agent, BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A, respectively, were synthesized, purified, and characterized by MALDI (matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization) mass as given elsewhere.35 Purity of these materials was determined between 96% and 98% by an analytical HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography) method.35

Samples of fresh mouse serum collected on the day of experiment and commercial human serum purchased from MP Biomedical (Solon, OH) were used in in vitro serum stability studies. Buffers were prepared and pH and ionic strength were controlled by using sodium monobasic phosphate, sodium dibasic phosphate, sodium acetate, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid, and sodium chloride (all from Fisher, Fair Lawn, NJ), respectively. Gibco 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) buffer for pH control was supplied by Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Acetonitrile and water (both from Fisher) containing trifluoroacetic acid (Chem Impax International, Wood Dale, IL) were used for mobile phase preparations. A sample of 153gadolinium chloride (153GdCl3, specific activity = 78.11 mCi/mg Gd, t1/2 of 241.6 days) for radiolabeling of BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Shelton, CT).

A block heater (Labnet International, Edison, NJ) was used for controlling reaction temperature at 95°C during synthesis of 153Gd-labeled AMBA, BVD15-DO3A, and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A. Similarly, the incubation temperature of the mixtures of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A and mouse or human serum samples was maintained at 37°C using the block heater. All pH measurements were made with a combination glass electrode and a Model S220 pH/Ion meter (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH). A model 1100 Agilent HPLC system (Agilent, Wilmington, DE) was used for the analysis of mouse or human serum stability samples for in vitro metabolic degradation of BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A. The system consisted of a quaternary pump, degasser, column compartment capable of controlling temperature at ambient or at 37°C, auto injector, and a multiwavelength/diode array detector controlled by Agilent's Chem Station software. A Flow Scintillation Analyzer (FSA 150) from Perkin Elmer or a Flow Ram from Lab Logic Systems (Sheffield, UK) was used for detection of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A. A Waters (Milford, MA) Zorbax Bonus RP C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm) was used for analysis of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A samples and for the separation of the 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A and its in vitro metabolic degradants in mouse and human serum stability samples. The percentage intact 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A was calculated from the main peak area of the corresponding compound.

The 153Gd-labeled AMBA, BVD15-DO3A, and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A) were prepared by a standard procedure developed in our laboratories. In a typical experiment, a stock sample solution (0.2 mg/mL, ∼60–120 μM) of an HPLC purified BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A was prepared by dissolving an appropriate amount of the peptide chelating agent conjugate in the known amount of Milli Q water. A sample of 153GdCl3 (∼100–200 μCi with 0.04 μM of nonradioactive Gd3+) in 0.01 M HCl was then mixed with an excess of AMBA or BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A (0.07 μM). The reaction mixture was heated at 95°C in the heating block for ∼10 minutes. The pH of the reaction mixture was then slowly raised to ∼7.0 (checked with a pH paper) using 0.1 M sodium acetate and diluted sodium hydroxide solutions with intermittent heating at 95°C for 15–20 minutes.

A reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) method, involving a gradient mobile phase system of water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid with 1 mL/min flow rate, was used to monitor the extent of the reaction of 153Gd/Gd with AMBA, BVD15-DO3A, and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A and for the purity analysis of the final 153Gd-labeled samples. A gradient program used was 0% B for 5 minutes, raising percentage B to 100% in 30 minutes, and followed by decreasing percentage B to 0% in 5 minutes and continuing 0% for an additional 5 minutes.

For the mouse serum stability studies, 0.1 mL 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A was spiked into 0.9 mL fresh mouse serum (both were pre-equilibrated at 37°C) in an HPLC glass vial and incubated at 37°C. The sample was then injected onto an RP-HPLC column without further sample clean up or manipulation. The in vitro metabolic degradation of the 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A was monitored with time by an RP-HPLC method as already described for the analysis of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A samples. Control experiments, in the absence of mouse serum, were conducted for comparison.

The procedure used for mouse serum stability studies could not be used for human serum stability studies because of the higher viscosity of samples containing human serum than the samples containing mouse serum. The human serum samples were difficult to inject and created high pressure in the HPLC system. A literature procedure was followed for the human serum stability studies of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A.36 On the day of the experiment, a small portion of the frozen human serum was thawed at room temperature. A stock sample of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A or human serum was equilibrated at 37°C in the block heater initially. Several mixtures, containing 50 μL of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A (usually 50 to 55 μCi radioactivity and 0.02 to 0.03 μM of Gd3+) and 450 μL of human serum, were prepared in HPLC vials and incubated at 37°C in the block heater.

At a selected time point (15, 75, 165, and 270 minutes for 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and 5, 90, 160, and 360 minutes for 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A), a vial was taken out from the heating block and degradation of the 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A was stopped by adding cold (4°C) absolute ethanol (500 μL). The sample was cooled in an ice bath to precipitate serum proteins, centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 minutes, and 200 μL of supernatant solution was isolated and analyzed by an RP-HPLC method as already given. The samples were analyzed at the following time intervals: 17, 45, and 90 minutes and 23, 67, 127, 200, and 1140 minutes for mouse serum stability study of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A, respectively (which includes chromatographic run time for the intact compound to elute); and for 15, 75, 165, and 270 minutes and 5, 90, 160, and 360 minutes for human serum stability study of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A, respectively.

The analysis times for these samples were different because of differences in rate of degradations of the probes in mouse versus human serum, difference of in vitro serum stability of one probe versus another, and direct injections in mouse serum stability studies versus involvement of sample cleanup/manipulation in human serum stability studies. Regardless of time points of analysis, the percentage of peak area of the intact compound versus time was used for calculations of the t1/2 resulting in no impact on the results. A gradient program (consisting solvent A & B given already) used was 0%–5% B in 5 minutes, 5%–70% B in 25 minutes, raising to 100% in next 5 minutes, and finally bringing down B to 5% in 5 minutes and followed by equilibration of the column. In parallel, control experiments were conducted under similar conditions by substituting human serum by PBS.

All degradation data of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A or t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A were analyzed using Excel or Graph Pad Prism version 5.03 software (Graph Pad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results and Discussion

Characterization of 153Gd-labeled AMBA, BVD15-DO3A, and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A

153Gd-labeled AMBA, BVD15-DO3A, and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A were analyzed for radio activity concentration and for radiochemical purity (RCP) by using a dose calibrator and a revered-phase HPLC (conditions already given) method, respectively. The retention times (minutes), radio concentration (μCi/mL), specific activity (Ci/mmol), and RCP (%) were the following: 153Gd-labeled AMBA 16.0 minutes, 400 μCi/mL, 11 Ci/mmol, 100%; 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A 15.3 minutes, 110 μCi/mL, 2.7 Ci/mmol, 98.8%; and 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A 17.5 minutes, 110 μCi/mL, 2.7 Ci/mmol, 97.7%–99.3%. Based on these retention times, a lipophilicity order for these peptide conjugates is t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A > AMBA > BVD15-DO3A.

Mouse and human serum stability study of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A

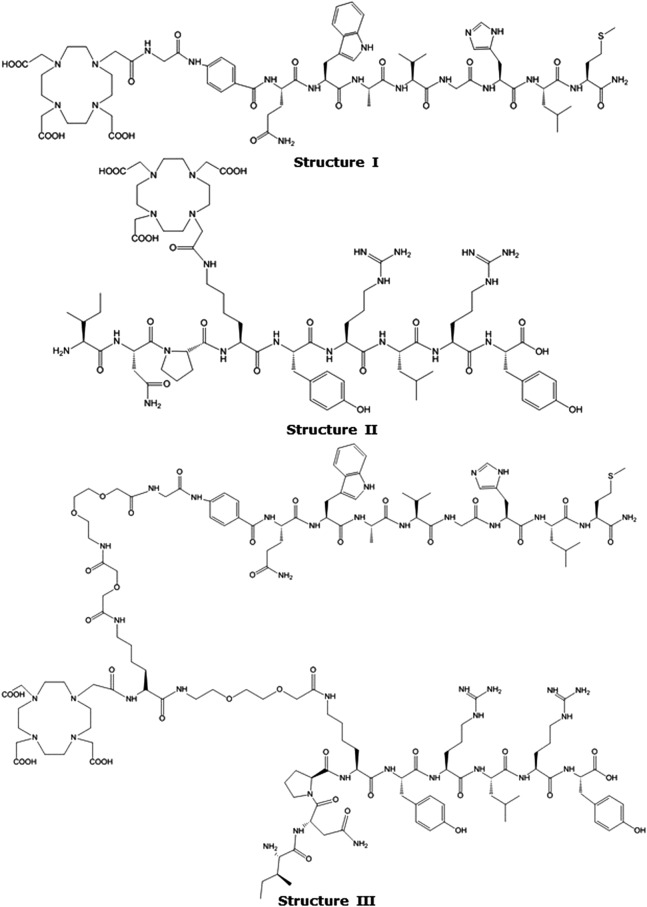

Several truncated NPY analogues derived from BVD15 have been tested in the past and they have shown good binding affinity to NPY1 receptors; however, limited information is available related to their serum stability. Consequently, we synthesized, 153Gd-labeled, and conducted mouse serum stability studies of BVD15-DO3A. For these experiments, a 0.1 mL 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A was spiked in 0.9 mL fresh mouse serum and incubated at 37°C. The sample was analyzed at 17, 45, and 90 minutes (including chromatographic run time for the intact compounds peak to elute) by the analytical HPLC method already described (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

HPLCs of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A incubated in mouse serum for 17 minutes (top), 45 minutes (middle), and 90 minutes (bottom) at 37°C. HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography.

The percentage peak areas summarized in Table 1 clearly show that 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A degraded in mouse serum with 97.0%, 33.7%, and 3.7%, present as intact compound, after 17, 45, and 90 minutes incubation, respectively. On the contrary, no significant degradation was observed in the control experiments, that is, 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A without mouse serum. As 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A in mouse serum degraded, new peaks at lower retention times (3.8 and 12.8 minutes or 0.25 and 0.85 relative retention times [RRTs]) appeared in the chromatograms and increased with incubation times, suggesting that these are less lipophilic 153Gd-labeled fragments of BVD15-DO3A. Moreover, two peaks at 13.7 and 14.5 minutes (0.91 and 0.95 RRTs) increased with time and finally decreased because of secondary degradation of the degraded peptide. After 90 minutes of incubation in mouse serum, almost all of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A degraded into equal amounts (∼45% each) of two major degradants with peaks that eluted at 3.8 and 12.8 minutes (0.25 and 0.85 RRTs), respectively. All these peaks were radioactive, suggesting that 153Gd is still chelated to the DO3A moiety and conjugated to a peptide fragment. Most likely, the early eluting peak at 3.8 minutes is hydrophilic and corresponds to 153Gd(DO3A-amide).37 No significant free or unbound 153Gd3+ or free 153Gd3+was detected in these studies, which is consistent with our previously published long-term in vivo stability studies of DO3A type 153Gd-labeled macrocyclic chelates.38

Table 1.

Percentage Peak Areas and Retention Times for 153Gd-Labeled BVD15-DO3A and Its In Vitro Metabolic Degradants After Incubation in Mouse Serum at 37°C

| Peak identity (minutes) | 3.8 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 12.4 | 12.8 | 13.7 | 14.4 | 15.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation time | Percentage peak areas (hereunder) | |||||||

| 17 minutes | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 97.1 |

| 45 minutes | 7.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 38.3 | 13.8 | 5.4 | 33.7 |

| 90 minutes | 46.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 44.5 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 3.7 |

The rate of degradation of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A in mouse serum was calculated by fitting the percentage intact BVD15-DO3A versus incubation time (Table 1) data in a first-order kinetics model. A t1/2 for degradation of 153Gd-labeled BVD-DO3A in mouse serum was calculated as 15 minutes. A similar short t1/2 (2 minutes) for Lys(NCS-Bn-NOTA)BVD15 in mouse plasma was measured by Liu et al.28 The short in vitro t1/2 of BVD15-DO3A, although exhibiting strong affinity to NPY1 receptors, means that it does not have high potential for in vivo imaging or radio therapeutic studies in mice.

A new late eluting peak (14.35 minutes or 1.03 RRT and ∼29% peak area), intact 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A (13.9 minutes and ∼62% peak area), and several other minor peaks (3.9, 12, and 13 minutes or 0.28, 0.86, and 0.94 RRTs with 2% to 3% peak areas, Table 2) were observed in the chromatogram of a mixture of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and human serum incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. The late eluting peak possibly is a human serum albumin (HSA) adduct39,40 of BVD15-DO3A. After 75 minutes incubation of the mixture, the 13.9 and 14.35 minutes peaks were significantly reduced, 26% and 2.8%, respectively. Several new peaks (Table 2) eluted at lower retention times, suggesting significant metabolic degradation of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A. Finally, two major peaks eluting at 3.2 and 3.5 minutes or 0.23 and 0.25 RRTs with ∼61% and 34% peak areas were seen in the chromatogram after 270 minutes incubation.

Table 2.

Percentage Peak Areas and Retention Times for 153Gd-Labeled BVD15-DO3A and Its In Vitro Metabolic Degradants After Incubation in Human Serum at 37°C

| Peak identity (minutes) | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 10.0 | 10.8 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 14.35 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation time | Percentage peak areas (hereunder) | |||||||||

| 15 minutes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 62.0 | 29.0 |

| 75 minutes | 22.9 | 0.0 | 11.3 | 16.4 | 5.5 | 45.0 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 26.3 | 2.8 |

| 165 minutes | 42.8 | 0.0 | 51.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 270 minutes | 61.4 | 33.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

A t1/2 for in vitro metabolic degradation of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A in human serum was estimated as 40 minutes, suggesting that it is three times more stable in human serum than in mouse serum. It is interesting that attachment of the chelating agent to BVD15 improves its serum stability as the t1/2 of [Lys4]BVD15 in human serum was reported to be very short, that is, only 0.5 minutes.28

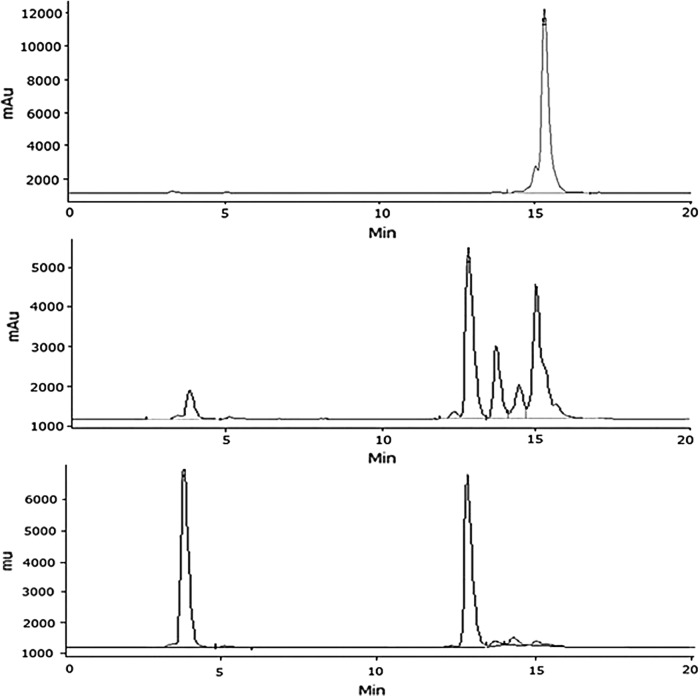

Mouse and human serum stability study of 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A

For the 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A mouse serum stability studies, the sample was analyzed at 23, 67, 127, 200, and 1140 minutes (including chromatographic run time for the intact compounds peak to elute) by the analytical HPLC method already described (Fig. 3). The percentage peak areas summarized in Table 3 show that 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A degraded more slowly in mouse serum than 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A. On the contrary, no significant degradation was observed in the control experiments, that is, 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A without mouse serum.

FIG. 3.

HPLCs of 153Gd-Labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A incubated in mouse serum for 23 minutes (top), 127 minutes (middle), and 1140 minutes (bottom) at 37°C.

Table 3.

Percentage Peak Areas and Retention Times for 153Gd-Labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A and Its In Vitro Metabolic Degradants After Incubation in Mouse Serum at 37°C

| Peak identity (minutes) | 3.3 | 11.9 | 12.6 | 13.2 | 14.2 | 15.6 | 16.5 | 17.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation time | Percentage peak areas (hereunder) | |||||||

| 23 minutes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 93.7 |

| 67 minutes | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.00 | 5.6 | 92.7 |

| 127 minutes | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 5.2 | 10.9 | 4.6 | 77.0 |

| 200 minutes | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 7.7 | 14.8 | 4.8 | 66.8 |

| 1140 minutes | 0.6 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 13.1 | 37.6 | 46.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

As 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A degraded, two new peaks at lower retention times (14–14.2 and 15.6 minutes or 0.81 and 0.90 RRTs) appeared in the chromatograms and increased with incubation times finally reaching to ∼38% and 46%, respectively, after 1140 minutes incubation. Some other minor peaks with <2% peak area were also seen, except for the 13.5 minutes peak that was <1% at initial time points but increased to ∼13% after 1140 minutes incubation. All these peaks are radioactive suggesting 153Gd3+ is still chelated to the DO3A moiety conjugated to peptide fragments. The retention times of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and AMBA are 15.3 and 16.0 minutes, respectively, under these mobile phase conditions, suggesting that most likely the peaks eluting at 14.2 and 15.6 minutes are 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and AMBA like or their fragments. No early eluting peaks for 153Gd (DO3A-amide) of free/unbound 153Gd3+ were detected in this study.

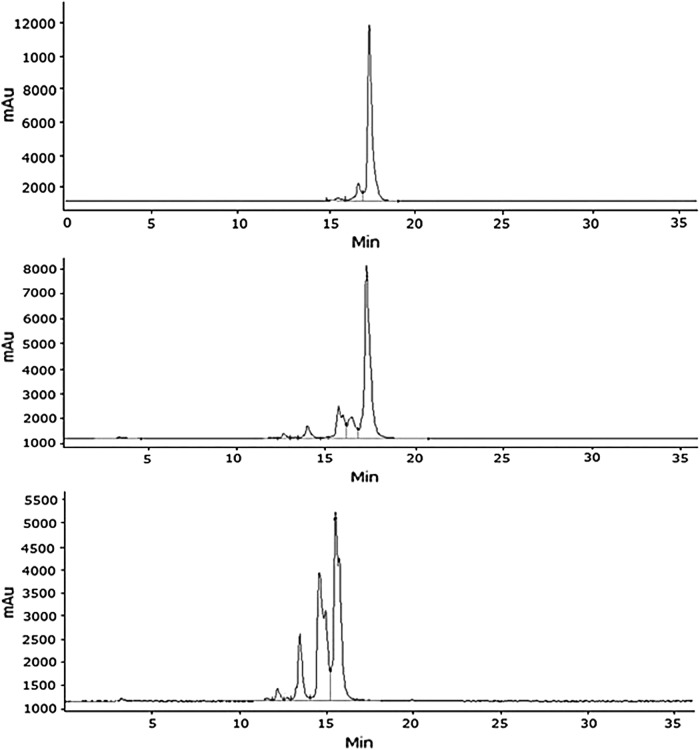

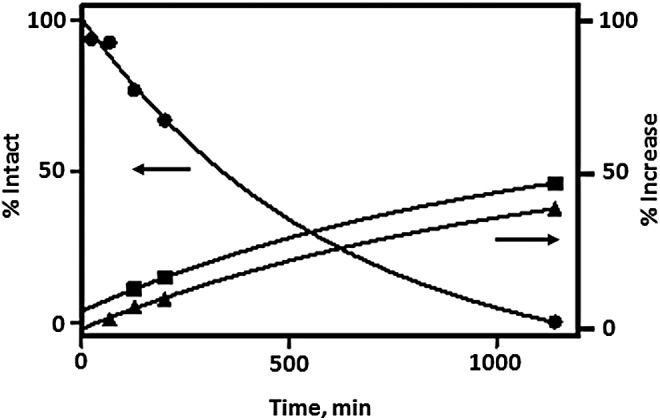

Figure 4 showed the percentage intact (17.3 minutes peak) of 153Gd-lableled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A and percentage increase for the two new peaks at 14.2 and 15.6 minutes in the HPLCs after mouse serum incubation at various time points. The data were fitted to One Phase decay/increase curve and yielded t1/2 values of 422, 728, and 763 minutes for the 17.3, 15.6, and 14.2 minutes peaks, respectively. The mouse serum t1/2 (422 minutes or 7 hours) of 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A was significantly greater than the mouse serum t1/2 of BVD15-DO3A (15 minutes) and of AMBA (186 minutes).22 Moreover, it is interesting that degradation of 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A produces two stable moieties that have similar chromatographic behavior as 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and AMBA.

FIG. 4.

Percentage remaining of 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A (RT = 17.3 minutes, solid circle) and percentage increase of the two in vitro metabolic degradants (RT = 15.6, solid square; and RT = 14.2 minutes, solid triangle) after 23, 67, 127, 200, and 1140 minutes incubation in mouse serum at 37°C.

After 5 minutes incubation of 153Gd-labeled t-BBN/BV15-DO3A in human serum, a new peak appeared at ∼17.3 minutes or ∼1.03 RRT (20% peak area, Table 4), possibly because of the formation of an HSA adduct of the compound,39,40 along with the peak of the intact compound at 16.8 minute (∼70%), which increased to ∼91% after 1.5 hours incubation. After 6 hours incubation, the 17.3 minutes peak equilibrated to 16.8 minutes (∼46% peak area) and another peak at 17.5 minutes. Several other metabolic degradants eluting at lower retention times with ∼4–7% peak areas were observed (Table 4), concluding ∼20% degradation in this period.

Table 4.

Percentage Peak Areas and Retention Times for 153Gd-Labeled t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A and Its In Vitro Metabolic Degradants After Its Incubation in Human Serum at 37°C

| Peak identity (minutes) | 3.3 | 3.5 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 16.0 | 16.8 | 17.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incubation time | Percentage peak areas (hereunder) | ||||||

| 5 minutes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 5.1 | 70.3 | 19.8 |

| 90 minutes | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.3 | 91.1 |

| 160 minutes | 0.0 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.7 | 87.7 |

| 360 minutes | 6.7 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 7.2 | 4.8 | 45.6 | 33.3 |

Conclusions

In vitro metabolic degradation of the dual-target probe, t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A, in mouse and human serum at 37°C is significantly slower than corresponding monomeric probes, AMBA and BVD15-DO3A. Two major in vitro metabolic degradants are proposed for each probe after mouse serum incubation of 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A and t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A. (1) 153Gd-labeled BVD15-DO3A degrades to 153Gd(DO3A-amide) and a 153Gd(DO3A) fragment of BVD15. (2) 153Gd-labeled BBN/BDV15-DO3A degrades primarily to two 153Gd(DO3A) fragments of t-BBN and BVD15. The relatively high mouse and human serum stability of the t-BBN/BVD15-DO3A heterobivalent molecule is sufficient for preclinical and clinical testing, but preclinical testing in mice is unlikely to predict human behavior.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds available from P30CA016058 (James Cancer Center) and TECH09-028 (OIRAIN) grants, the Stefanie Spielman Foundation, and the Wright Center. The authors are grateful to Professor Michael V. Knopp (Director and PI of Wright Center of Innovation in Biomedical Imaging) for his encouragement and support during conduct of these studies.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA: A Cancer J Clin 2001;51:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veronesi U, Boyle P, Goldhirsch A, et al. Breast cancer. Lancet 2005;365:1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reubi JC. Peptide receptors as molecular targets for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Endocr Rev 2003;24:389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornelio DB, Roesler R, Schwartsmann G. Gastrin-releasing peptide receptor as a molecular target in experimental anticancer therapy. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reubi JC, Gugger M, Waser B. Co-expressed peptide receptors in breast cancer as a molecular basis for in vivo multi receptor tumour targeting. Eur J Nucl Med 2002;29:855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Magni P, Motta M. Expression of neuropeptide Y receptors in human prostate cancer cells. Ann Oncol 2001;12:S27 (b) Ruscica M, Dozio E, Boghossian S, Bovo G, Martosriano V, Motta M, Magni P. Activation of Y1 receptor by neuropeptide Y regulates the growth of prostate cancer cells. Endocrinology 2006;147:1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ansquer C, Kraeber-Bodere F, Chatal JF. Current status and perspective in peptide receptor radiation therapy. Curr Pharm Des 2008;15:2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cabrele C, Beck-Sickinger AG. Molecular characterization of ligand-receptor interaction of neuropeptide Y family. J Pept Sci 2000;6:97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Rice S, Roney C, Daumar P, Lewis J. The next generation of positron emission tomography radiopharmaceuticals in oncology. Semin Nucl Med 2011;41:265 (b) Delbeke D. Oncological applications of FDG PET imaging: Brain tumors, colorectal cancer, lymphoma and melanoma. J Nucl Med 1999;40:591. (c) Glaser M, Luthra S, Brady F. Applications of positron-emitting halogens in PET oncology. Int J Oncology 2003;22:253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.For Reviews See (a) Fani M, Maecke HR. Radiopharmaceutical development of radiolabelled peptides. Eur J Nuc Med Mol Imaging 2012;39:S11 (b) Correia JDG, Paulo A, Raposinho PD, Santos, I. Radiometallated peptides for molecular imaging and targeted therapy. Dalton Trans 2011;40:6144. (c) Schottelius M, Wester H-J. Molecular imaging targeting peptide receptors. Methods 2009;48:161. (d) Tweedle MF. Peptide-targeted diagnostics and radiotherapeutics. Acc Chem Res 2009;42:958. (e) Fani M, Maecke HR, Okarvi SM. Radiolabeled peptides: Valuable tools for the detection and treatment of cancer. Theranostics 2012;2:481. (f) Smith CJ, Volker WA, Hoffman TJ. Radiolabeled peptide conjugates for targeting of bombesin receptor superfamily subtypes. Nucl Med Biol 2005;32:733. (g) Moreno P, Ramos-Alvarez I, Moody TW, Jensen RT. Bombesin related peptides/receptors and their promising therapeutic roles in cancer imaging, targeting and treatment. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2016;20:1 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lane SR, Veerendra B, Rold TL, et al. 99mTc(CO)3-DTMA bombesin conjugates having high affinity for the GRP receptor. Nucl Med Biol 2008;35:263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin K-S, Luu A, Baidoo KE, Haschemzadeh-Gargari H, Chen M-K, Brenneman K, Pili R, Pomper M, Carducci MA, Wagner HN., Jr A new high affinity technetium-99m-bombesin analog with low abdominal accumulation. Bioconjug Chem 2005;16:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alves S, Paulo A, Correia DG, et al. Pyrazolyl derivatives as bifunctional chelators for labeling tumor-seeking peptides with the fac-[M(CO)3]+ moiety (M = 99mTc, Re): Synthesis, characterization, and biological behavior. Bioconjug Chem 2005;16:438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith CJ, Gali H, Sieckman GL, et al. Radiochemical investigations of 177Lu-DOTA-8-Aoc-BBN[7-14]NH2: An in vitro/in vivo assessment of targeting ability of this new radiopharmaceutical for PC-3 human prostate cancer cells. Nucl Med Biology 2003;30:101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Schuhmacher J, Waser B, et al. DOTA-PESIN, a DOTA-conjugated bombesin derivative designed for imaging and targeted radionuclide treatment of bombesin receptor-positive tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag 2007;34:1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Visser M, Bernard HF, Erion JL, et al. Novel 111In labelled bombesin analogues for molecular imaging of prostate tumours. Eur J Nuc Med Mol Imaging 2007;34:1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parry JJ, Andrews R, Rogers BE. Micro PET imaging of breast cancer using radiolabeled bombesin analogs targeting the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2007;101:175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lears KA, Ferdani R, Liang K, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of 64Cu-labeled SarAr-bombesin analogs in gastrin-releasing peptide receptor-expressing prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2011;52:470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasanphanich AF, Nanda PK, Rold TL, et al. [64Cu-NOTA-8-AOC-BBN(7-14)NH2] targeting vector for positron-emission tomography imaging of gastrin-releasing peptide receptor-expressing tissues. PNAS 2007;104:12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lane SR, Nanda P, Rold TL, et al. Optimization, biological evaluation and micro PET imaging of copper-64-labeled bombesin agonists, [64Cu-NO2A-(X)-BBN(7-14)NH2], in prostate tumor xenografted mouse model. Nucl Med Biol 2010;37:751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrison JC, Rold TL, Sieckman GL, et al. In vivo evaluation and small-animal PET/CT of a prostate cancer mouse model using 64Cu bombesin analogs: Side-by-side comparison of CB-TE2A and DOTA chelation systems. J Nucl Med 2007;48:1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lantry LE, Cappelletti E, Maddalena ME, et al. 177Lu-AMBA: Synthesis and characterization of a selective 177Lu-labeled GRP-R agonist for systemic radiotherapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2006;47:1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maddalena ME, Fox J, Chen J, et al. 177Lu-AMBA biodistribution, radiotherapeutic efficacy, imaging, and autoradiography in prostate cancer models with low GRP-R expression. J Nucl Med 2009;50:2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langer M, Bella RL, Garcia-Garayoa E, et al. 99mTc-labeled neuropeptide Y analogues as potential tumor imaging agents. Bioconjug Chem 2001;12:1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwangieger D, Khan IU, Neundorf I, et al. Novel chemically modified analogues of neuropeptide Y for tumor targeting. Bioconjug Chem 2008;19:1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniels AJ, Mathews JE, Slepetis RJ, et al. High-affinity neuropeptide Y receptor antagonists. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995;92:9067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerin B, Dumulon-Perreault V, Tremblay M-C, Ait-Mohand S, Fournier P, Dubuc C, Authier S, Benard F. [Lys(DOTA)4]BVD15, a novel and potent neuropeptide Y designed for Y1 receptor-targeted breast tumor imaging. Biorg Med Chem Letters 2010;20;950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu M, Mountford SJ, Zhang L, et al. Synthesis of BVD15 peptide analogues as models for radio ligands in tumour imaging. Int J Pep Res Ther 2013;19:33 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yan Y, Chen X. Peptide heterodimers for molecular imaging. Amino Acids 2011;41:1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo H, Hong H, Yang SP, et al. Design and applications of biospecific heterodimers: Molecular imaging and beyond. Mol Pharm 2014;11:1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang L, Miao Z, Liu H, et al. 177Lu-labeled RGD-BBN heterodimeric peptide for targeting prostate carcinoma. Nucl Med Comm 2013;34;909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durkan K, Jiang Z, Rold TL, et al. A heterodimeri [RGD-Glu-[64Cu-NO2A]-6-Ahx-RM2] αvβ3/GRPr-targeting antagonist radiotracer for PET imaging of prostate tumors. Nuc Med Biol 2014;41:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Oliveira EA, Faintuch BL, Targino RC, et al. Evaluation of GX1 and RGD-GX1 peptides as new radiotracers for angiogenesis evaluation in experimental glioma models. Amino Acids 2016;48:821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuhn KK, Ertl T, Dukorn S, et al. High affinity agonists of neuropeptides Y (NPY) Y4 receptor derived from the C-terminal pentapeptide of hyman pancreatic polypeptide (hPP): Synthesis, stereochemical discrimination, and radiolabeling. J Med Chem 2016;59:6045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shrivastava A, Wang S-H, Raju N, et al. Heterobivalent dual-target probe for targeting GRP and Y1 receptors on tumor cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2013;23:687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gottumukkala V, Heinrich TK, Baker A, et al. Biodistribution and stability studies of [18F]fluoroethylrhodamine B, a potential PET myocardial perfusion agent. Nucl Med Biol 2010;37:365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar K, Sukumaran K, Taylor S, et al. Partition coefficients (log P) and HPLC capacity factor (k′) of some Gd(III) complexes of linear and macrocyclic polyaminocarboxylatesd. J Liq Chromatography 1994;17:3735 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wedeking P, Kumar K, Tweedle MF. Dissociation of gadolinium chelates in mice: Relationship to chemical characteristics. Mag Res Imag 1992;10:641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milojevic J, Melacini G. Stoichiometry and affinity of human serum albumin-Alzheimer's A β peptide interactions. Biophys J 2011;100:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadatmousavi P, Kovalenko E, Chen P. Thermodynamic characterization of interaction between a peptide—Drug complex and serum proteins. Langmuir 2014;30:11122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]