Abstract

95% of patients with ductal pancreatic cancer carry 12th codon activating mutations in their KRAS2 oncogenes. Early whole body imaging of mutant KRAS2 mRNA activation in pancreatic cancer would contribute to disease management. Scintigraphic hybridization probes to visualize gene activity in vivo constitute a new paradigm in molecular imaging. We have previously imaged mutant KRAS2 mRNA activation in pancreatic cancer xenografts by positron emission tomography (PET) based on a single radiometal, 64Cu, chelated to a 1,4,7,10-tetra(carboxymethylaza)cyclododecane (DOTA) chelator, connected via a flexible, hydrophilic spacer, aminoet-hoxyethoxyacetate (AEEA), to the N-terminus of a mutant KRAS2 peptide nucleic acid (PNA) hybridization probe. A peptide analogue of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), connected to a C-terminal AEEA, enabled receptor-mediated endocytosis. We hypothesized that a polydiamidopropanoyl (PDAP) dendrimer (generation m), with increasing numbers (n) of DOTA chelators, extended via an N-terminal AEEA from a mutant KRAS2 PNA with a C-terminal AEEA and IGF1 analogue could enable more intense external imaging of pancreatic cancer xenografts that overexpress IGF1 receptor and mutant KRAS2 mRNA. ([111In]DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 analogues were prepared and administered intravenously into immunocompromised mice bearing human AsPC1 (G12D) pancreatic cancer xenografts. CAPAN2 (G12 V) pancreatic cancer xenografts served as a cellular KRAS2 mismatch control. Scintigraphic tumor/muscle image intensity ratios for complementary [111In]n-PDAPm-KRAS2 G12D probes increased from 3.1 ± 0.2 at n = 2, m = 1, to 4.1 ± 0.3 at n = 8, m = 3, to 6.2 ± 0.4 at n = 16, m = 4, in AsPC1 (G12D) xenografts. Single mismatch [111In]n-PDAPm-KRAS2 G12 V control probes showed lower tumor/muscle ratios (3.0 ± 0.6 at n = 2, m = 1, 2.6 ± 0.9 at n = 8, m = 3, and 3.7 ± 0.3 at n = 16, m = 4). The mismatch results were comparable to the PNA-free [111In]DOTA control results. Simultaneous administration of nonradioactive Gdn-KRAS2 G12 V probes (n = 2 or 8) increased accumulation of [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probes 3–6-fold in pancreatic cancer CAPAN2 xenografts and other tissues, except for a 2-fold decrease in the kidneys. As a result, tissue distribution tumor/muscle ratios of 111In uptake increased from 3.1 ± 0.5 to 6.5 ± 1.0, and the kidney/tumor ratio of 111In uptake decreased by more than 5-fold from 174.8 ± 17.5 to 30.8 ± 3.1. Thus, PDAP dendrimers with up to 16 DOTA chelators attached to PNA-IGF1 analogs, as well as simultaneous administration of the elevated dose of nonradioactive Gdn-KRAS2 G12 V probes, enhanced tumor uptake of [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes. These results also imply that Gd(III) dendrimeric hybridization probes might be suitable for magnetic resonance imaging of gene expression in tumors, because the higher generations of the dendrimers, including the NMR contrast Gdn-KRAS2 G12 V probes, improved tumor accumulation of the probes and specificity of tumor imaging.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer will kill over 30 000 US men and women in 2010 (1). The vast majority of patients with pancreatic cancer present at an advanced, incurable stage. Even before an enlarged mass can be seen by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized tomography (CT), early stage pancreatic intraepi-thelial neoplasia cells contain high levels of mRNAs copied from hyperactive cancer genes such as KRAS2 and HER2 (2). 95% of patients with ductal pancreatic cancer carry 12th codon activating mutations in their KRAS2 oncogenes (2). Specific detection of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia by molecular imaging would enable resection of ductal pancreatic cancer at a survivable stage. Monitoring oncogene expression by radio-hybridization imaging might also provide the earliest possible evidence for therapeutic efficacy, or resistance, sooner than FDG-PET.

Scintigraphic imaging, such as planar or PET, is very sensitive, but only appropriate in a human subject when suspect masses are evident or highly likely. Nonradioactive fluorescent imaging and luminescent imaging are impractical for any suspect mass more than 2 cm below the surface of the skin. Nonradio-active MRI could be effective for molecular imaging of deep-seated malignant foci, particularly due to the high spatial resolution (up to 25–100 μm) of MRI (3). However, disadvantages of MRI include relatively low specificity and the requirement for large quantities of the injected probes containing gadolinium.

Noninvasive scintigraphic imaging of gene expression by detection of specific mRNAs in cells to diagnose cancer and other diseases in living systems has been attempted with antisense oligonucleotides (3–14). Specific imaging of target gene mRNA requires multiple steps: probe permeation into tissue, endocytosis into the cells, probe hybridization with the target mRNA, probe:mRNA accumulation in the specific cells, and effluxing of unbound probes. Nonhybridized probes must efflux from cells with little or no expression of the target mRNA in order to permit a specific image in the targeted cells.

We used peptide nucleic acids (PNA1) (15) because PNA is resistant to biological degradation and binds complementary mRNA with affinity, specificity, and stability exceeding those of corresponding DNA/RNA duplexes (16). PNA oligomers are uncharged, resulting in poor cellular uptake, which minimizes nonspecific binding to cells (17).

Receptor-mediated endocytosis of PNA drugs or diagnostic probes into malignant cells that overexpress insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) receptors can be accomplished with a short, cyclized IGF1 peptide analogue, D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys), separated from the C-terminus of the PNA by a flexible, hydrophilic aminoethoxyethoxyacetic acid (AEEA) spacer (9, 10, 13, 18). Alanine replacements in the peptide (9, 10, 12, 13, 18), or peptide blocking by native IGF1 (13), minimized internalization. Bonding radioactive metal cations to specific chelator-PNA-IGF1 analogues enabled their delivery to cells for radioimaging in xenografts in living subjects (9, 10, 12, 13).

In the case of activated KRAS2 G12D mRNA overexpressed in pancreatic cancer AsPC1 cells, the melting temperature, Tm, of the complementary KRAS2 G12D PNA 12-mer with a KRAS2 G12D RNA 20-mer was 80 °C, independent of the peptide ligand sequence (12), following the typical behavior of PNA: RNA duplexes (19, 20). A single mismatch, corresponding to the difference between the KRAS2 G12D mutant sequence and the KRAS2 G12 wild-type sequence, lowered the Tm by 20 °C. Three mismatches lowered the Tm by 30 °C. Those thermodynamic results predicted single mismatch hybridization specificity under intracellular conditions.

Uptake of [99mTc]SBTG2-DAP-AEEA-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 analogue by AsPC1 cells at 37 °C was 3-fold greater than accumulation of a corresponding CCND1 probe (21). Those results are consistent with greater cellular retention due to KRAS2 complementarity. Confocal fluorescence microscopic measurements of the mass transfer coefficients of AsPC1 cellular uptake of fluorescent analogues of the KRAS2 G12D PNA probes revealed 10-fold less uptake by dual amino acid mismatch probes (22).

[64Cu]DOTA-AEEA-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 analogues enabled PET imaging in pancreatic cancer AsPC1 G12D xenografts, with single base mismatch precision in the PNA. Tumor core PET contrast intensities were 8-fold greater than contralateral muscle PET intensities for the KRAS2 G12D complementary probe. Much lower tumor core PET intensities in the cases of G12 wild-type (one mismatch), G12 V (one mismatch), G12K (two mismatches), and G12E (three mismatches) sequence controls implied that PET imaging intensity depended upon accurate mRNA hybridization (12).

Similarly, a dual amino acid mismatch sequence in the IGF1 analogue, with a fully matched PNA sequence, reduced PET contrast intensities (12). Furthermore, reduced PET intensities were observed in G12 V single mismatch pancreatic CAPAN2 xenografts, after administration of the G12D probe, and in KRAS2− breast cancer BT474 xenografts. Four hours of distribution, cellular efflux, and systemic excretion were necessary before clear images could be obtained (12).

Those KRAS2 PET imaging experiments all depended on probes with a single chelator binding a single radionuclide. To increase mRNA-specific contrast by genetic probes, particularly for less abundant mRNAs, it would be desirable to increase the number of metal ions per hybridization probe. For that purpose, we designed novel polydiamidopropanoyl (PDAP) dendrimers with increasing numbers of primary amines by coupling Fmoc-AEEA monomers and Fmoc-diaminopropanoate (DAP) monomers to the N-terminus of PNA–peptide chimeras extended from polymer supports (23). To each amine, we coupled a DOTA chelator by one of its carboxylates, converting it into a DOTA moiety.

Recently, we reported the synthesis of (Gd-DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 analogue MRI contrast agents (24). MRI phantom experiments showed proportional increase of the MRI intensity and T1 relaxivity with increases in the number of Gd(III) chelated to those probes. To estimate the fraction of internalized GdnKRAS2 PNA agents that would be hybridized to available KRAS2 mRNAs in live tumor cells, the Tm of each probe was measured with increasing generations of the PDAP dendrimers hybridized to KRAS2 G12D 20-mer RNA. Fully matched (Gd-DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS G12D PNA-IGF1 analogues formed stable complementary PNA/RNA hybrid complexes with melting temperatures (Tm) of 79–80 °C. The generation of the PDAP dendrimers did not influence the Tm values of PNA/RNA hybrid duplexes. A single mismatch, corresponding to the single base difference between the G12D mutant sequence and the G12 V mutant sequence, lowered the Tm by 12 °C (24). These thermodynamic results predict single mismatch hybridization specificity for the dendrimeric PNA probes under intracellular conditions.

However, before evaluation of such dendrimeric probes for noninvasive molecular imaging of intracellular mRNA and oncogene expression, several questions must be addressed. First of all, how does the number of metal cations chelated to the PNA probes or the generation of PDAP dendrimers influence their uptake and accumulation in the tumor-targeted tissue and in other tissues? Second, how does the concentration of the dendrimeric PNA probes influence the imaging of the tumor? As a result of the sensitivity limitations of MRI with Gd(III) contrast, we chose to label the dendrimeric hybridization probes with 111In(III) [γ, 0.171, 0.245 MeV, half-life 67.32 h (2.8 d)] for scintigraphic imaging. Free, unchelated 111In(III) accumulates nonspecifically in the kidneys, liver, spleen, bone, and tumors of mice bearing colon, lung, or neuroblastoma xenografts (25). However, chelated 111In(III) is exceedingly stable, dissociating by no more than 1% in 10 days at 37 °C in the presence of serum, correlating with a binding constant of ~1024 (26).

Here, we report the sensitivity of noninvasive scintigraphic imaging of overexpressed oncogene KRAS2 mRNA with γ-emitting ([111In]DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS2 PNA-IGF1 analogues, WT5195, WT8900, and WT13842, specific for KRAS2 G12D or KRAS2 G12 V mRNA, with up to n = 16 111In(III) per probe. We investigated the accumulation of the [111In]nKRAS2 probes in immunocompromised mice bearing human AsPC1 (G12D) or CAPAN2 (G12 V) pancreatic cancer xenografts. We also investigated the effect of administering mixtures of 111In(III)-chelated PNA hybridization probes with increasing doses of nonradioactive Gd(III)-chelated hybridization probes in order to saturate nonspecific tissue binding sites. This approach permitted us to determine how the concentration and dendrimer generation of our Gd(III)-chelated agents influenced the specificity and intensity of KRAS2 mRNA scintigraphic imaging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of (DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 Analogue Nanoparticles

The unlabeled hybridization probes (Scheme 1, Table 1) containing 12-base PNAs flanked by the dendrimeric radionuclide chelators DOTA2, DOTA8, or DOTA16 at the N-terminus, and a short retro-inverso cyclized fragment of IGF1, D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys), at the C-terminus (Figure 1), were assembled by solid-phase synthesis from Fmoc-monomers, purified, and characterized as described (24), and in the Supporting Information.

Scheme 1.

(Metal-DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 Analogues

Table 1.

| name | label | sequence | calc. mass, Da. | obs. mass, Da | % yield | Tm, °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA2 G12D | WT5195 | (DOTA-AEEA)2-PDAP1-AEEA2-GCCAtCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 5194.65 | 5195.63 | 12.6 | 78.7 ± 0.6 |

| DOTA8 G12D | WT8900 | (DOTA-AEEA)8-PDAP3-AEEA2-GCCAtCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 8900.47 | 8901.06 | 2.4 | 75.9 ± 0.5 |

| DOTA16 G12D | WT13842 | (DOTA-AEEA)16-PDAP4-AEEA2-GCCAtCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 13841.57 | 13843.50 | 0.57 | 74.1 ± 1.0 |

| DOTA2 G12 V | WT5204 | (DOTA-AEEA)2-PDAP1-AEEA2-GCCAaCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 5203.7 | 5204.6 | 20.2 | 68.0 ± 1.2 |

| DOTA8 G12 V | WT8910 | (DOTA-AEEA)8-PDAP3-AEEA2-GCCAaCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 8909.5 | 8911.9 | 11.5 | 66.9 ± 0.5 |

| DOTA16 G12 V | WT13851 | (DOTA-AEEA)16-PDAP4-AEEA2-GCCAaCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 13850.6 | ND | 6.8 | 68.8 ± 0.5 |

| Gd2 G12 V | WT5512 | (Gd-DOTA-AEEA)2-PDAP1-AEEA2-GCCAaCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 5512.2 | 5514.0 | 16.6 | 68.0 ± 1.0 |

| Gd8 G12 V | WT10144 | (Gd-DOTA-AEEA)8-PDAP3-AEEA2-GCCAaCAGCTCC-AEEA-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) | 10143.5 | 10143.6 | 5.8 | 66.8 ± 0.9 |

Masses were measured by MALDI TOF MS or ESI-MS. Yields were calculated with respect to initial amino acid loading of the resin beads. Melting temperatures are shown ± standard errors of the means. ND: not done.

Figure 1.

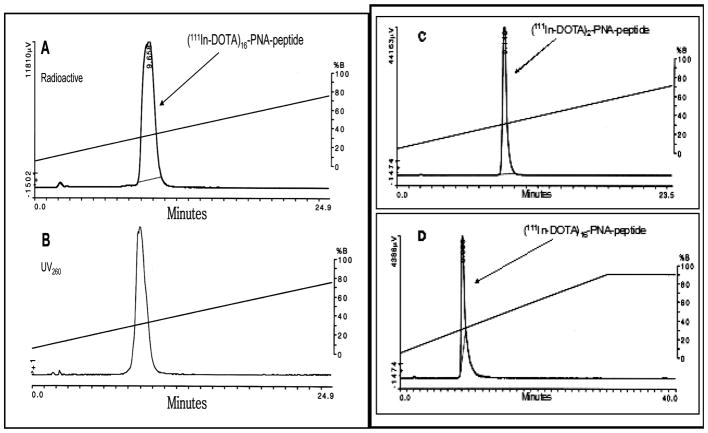

C18 HPLC profiles of [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes, eluted as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Analytical radioactivity profile of [111In]16KRAS2 G12D, WT13842. (B) Analytical absorbance profile at 260 nm of [111In]16KRAS2 G12D, WT13842. (C) Analytical radioactivity profile of [111In]2KRAS2 G12D, WT5195, in the combined urine from 3 immunocompromised mice bearing AsPC1 xenografts 3.5 h after tail vein administration. (D) Analytical radioactivity profile of [111In]16KRAS2 G12D, WT13842, in the combined urine from 3 immunocompromised mice bearing AsPC1 xenografts 3.5 h after tail vein administration.

Radiolabeling of DOTAn-KRAS2 PNA Probes with 111In(III)

DOTAn-KRAS2 PNA probes (n = 2, 8, 16; G12D and G12 V KRAS2 mutants, Table 1) were labeled with 111In(III) essentially as described (6). Briefly, 5–10 μL of 111InCl3 at 3.7–7.4 MBq/μL (100–200 μCi/μL) in 0.05 M HCl (MDS Nordion, Kanata, ON, Canada) containing 37 MBq (1 mCi) (~21 pmol, assuming the specific activity for carrier-free 111InCl3, 1.723 GBq/nmol, 46.6 Ci/μmol), were incubated with 45μL of 0.10–0.15 mM (~6 nmol) of the indicated DOTAn-KRAS2 PNA probes in 0.10 M NaOAc, pH 7.0, for 15 min at 80 °C. The radiolabeling yield (typically >95%) was analyzed by HPLC as below. Thus, the final specific activity of the PNA probes, assuming stoichiometric chelation, was ~6 MBq/nmol (0.17 Ci/μmol). Similarly, 500 nmol of DOTA was labeled with 74 MBq (2 mCi) (~42 pmol) of 111In as a control probe, with a calculated specific activity of ~0.15 MBq/nmol (0.004 Ci/ μmol) in a final volume of 100 μL.

Solutions were diluted with 100 μL of 0.9% saline. Aliquots of each labeling mixture (10–14 μCi, 0.37–0.52 MBq) were analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC on a 4.6 × 150 mm C18 column (Altima, Alltech) coupled to a UV detector, NaI (Tl) radioactivity monitor, and a rate meter. The column was eluted with a 30 min gradient from 4% to 72% CH3CN in aqueous 0.1% CF3CO2H, at 1 mL/min, at 23 °C. Other aliquots of the labeling mixtures (250–350 μCi, 9.0–13.0 MBq) after dilution with 0.9% saline up to a total volume of 200 μL were used for tail vein administration into mice to image tumors.

In Vitro Stability

Labeled probes were tested for stability in 0.9% saline, and with 100-fold molar excesses of diethyl-enetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), human serum albumin, or cysteine at 22 °C for more than 2 days. Stability was determined by HPLC as above.

Chelation of DOTAn-KRAS2 PNA Probes with Gd(III)

DOTAn-KRAS2 PNA probes (n = 2, 8, 16; G12 V KRAS2 mutants, Table 1), 0.5 mM in 0.1 M NaOAc, pH 6.0, were incubated with at least a 10-fold excess of GdCl3 at 80 °C for 15 min to maximize chelation, as described (24). Spectrophotometric quantitation of remaining unchelated Gd(III) ions was carried out by titration with 1 mM DTPA solution in water in the presence of arsenazo III dye, which changes from a cherry-red color with a peak at 665 nm to a blue color after forming a specific Gd(arsenazo III)2 complex in 0.15 M NaOAc, pH 4 (27, 28). 90–98% of the DOTA residues in the hybridization probes were occupied by Gd(III) ions. The final Gd-chelated products were purified on a 22 × 250 mm Alltima C18 column eluted with a linear 30 min gradient from 0% to 30% CH3CN in aqueous 0.1% CF3CO2H, at 10 mL/min, at 50 °C, monitored at 260 nm (24).

Cell Culture and Xenografts

The human pancreatic cancer cell line AsPC1 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), isolated from ascites of a female patient with invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma (29), expresses a 12th codon GGT→GAT, G12D mutant KRAS2 oncogene (30), and over-expresses IGF1R (31). As a KRAS2 sequence control, the human pancreatic cancer cell line CAPAN2 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD), which was isolated from a male patient with invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma (32), expresses a 12th codon GGT→GTT, G12 V mutant KRAS2 oncogene (33), and overexpresses IGF1R (34). Pancreatic cancer cells were maintained in log phase in RPMI 1640 (AsPC1) or McCoy’s 5a (CAPAN2) media supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 5000 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2/95% air and cultured to 80% confluence prior to splitting or implantation. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of total RNA from AsPC1 cells yielded about 20 000 KRAS2 mRNA per cell (12).

For tumor induction, approximately (5–6) × 106 cells in 0.2 mL of culture medium were implanted intramuscularly through a sterile 27 gauge needle into the thighs of 6–8-week-old 20–25 g female immunocompromised NCR mice obtained from NCI. Tumors were grown to no more than 1 cm in diameter. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with federal and state guidelines governing the laboratory use of animals, and under approved protocols reviewed by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Thomas Jefferson University. All animals were anesthetized by approved methods, and when required, the animals were restrained using methods and devices specifically designed to provide a minimum of discomfort to the animal. Animals were euthanized in a halothane chamber, consistent with USDA regulations and American Veterinary Medical Association recommendations.

Systematic Administration and Tissue Distribution of Labeled Probes

To assess KRAS2 probe imaging and distribution, 7.4–11.1 MBq (200–300 μCi), ~2 nmol, of the [111In]n-KRAS2 G12D and G12 V probes in 0.2 mL of sterile 0.14 M NaCl, pH 7, was administered to groups of 3–5 mice with xenografts each through a lateral tail vein using a sterile 27 gauge needle. Distributions were also measured for mixtures of [111In]nKRAS2 G12 V probes with an additional 11, 48, or 94 nmol of Gdn-KRAS2 G12 V probes. ~11 MBq (~300 μCi), 80 nmol, of [111In]DOTA was administered as a control. Free, unchelated 111In(III) was not used as a control due to its nonspecific accumulation in the kidneys, liver, spleen, bone, and tumors of mice bearing a variety of xenografts (25).

At 4, 8, and 24 h postinjection, mice were lightly anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (200 mg/kg), xylazine (10 mg/kg), and acetopromazine (2 mg/kg), then imaged using a Starcam (GE Medical, Milwaukee, WI) gamma camera equipped with a parallel hole collimator. For each image, 300 000 counts were collected. Digital scanning of region-of-interest intensities with the interfaced Integra computer (GE Medical) across each scintigraphic image from the tumor-free left flank to the tumor-bearing right flank provided quantitation of tumor images. Statistical significance was assessed by standard error of the means, assuming normal distributions.

After 24 h, mice were euthanized. Portions of muscle, intestine, heart, lungs, blood, spleen, kidneys, liver, and tumor were collected. We did not attempt to dissect out the pancreas, because in mice, the pancreas is remarkably small and wrapped tightly around the small intestine. Portions of tail were not collected separately from muscle, because previous imaging experiments had not shown excess residual probe remaining in the tails. The dissected tissues were washed free of blood, blotted dry, and weighed, and radioactivity associated with each tissue was counted in an automatic gamma counter (Packard Series 5000, Meridien, CT), together with a standard radioactive solution of a known quantity prepared at the time of injection. Results were expressed as percent of injected dose per gram of tissue (% ID/g). Null probabilities were calculated by Student’s t test.

In Vivo Stability

Analysis of urine samples will reveal catabolism of labeled probes occurring throughout the body of the animals. [111In]chelates are so strong as to preclude transchelation to serum proteins (26). Urine was collected up to 3.5 h postinjection from groups of 3–5 mice injected with radiohybridization probes for assessment of probe stability. The urine samples were combined, sedimented at 2000 × g for 10 min, filtered through Millipore HAWP 025 membranes with 0.22 μm pores, and analyzed by RP-HPLC as described in Radiolabeling.

RESULTS

Characterization of (DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 Nanoparticles

Theoretically, the number of free amino groups on the growing PDAP dendrimers on the polymer support at each generation should double at each coupling. The number of amino groups available at each generation was determined by measuring the absorbance of the dibenzofulvene-piperidine adduct (ε301 = 7800 M−1 cm−1) released upon Fmoc deprotection after each coupling of (Fmoc)2-DAP-COOH as described (24). The number of Fmoc deprotection residues released from the growing PDAP dendrimers at each step increased from 1.00 to 2.00, 3.98, then 7.61 (95.0% yield) for PDAP3 with 8 theoretical amines, as reported (24). For PDAP4 dendrimers with 16 theoretical amines, Fmoc deprotection residues released increased from 1.00 to 1.95, 3.82, 7.58, then 14.16 (88.5% yield) (24).

Analysis of [111In]nKRAS2 PNA Probes

A ≥600-fold excess of DOTA residues (≥15 nmol) over ~21 pmol of 111InCl3 promoted chelation of 111In(III) to DOTA-dendrimer PNA probes. The lack of free 111In(III) permitted administration of [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes directly after labeling. Before administration to mice, aliquots of radiolabeled probes were analyzed by HPLC, monitoring with both UV detector at 260 nm and with NaI (Tl) radioactivity monitoring detector. Analytical HPLC of the [111In]16KRAS2 G12D probe WT13842 is shown as an example (Figure 1AB). Generations 1 and 3 are shown in Figures S1 and S2 in the Supporting Information. On the basis of the HPLC results, routine radiochemical yields of more than 95% with specific activities of ~6 MBq/nmol (0.17 mCi/nmol) of [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes were obtained. Theoretically, >600-fold greater specific activity of [111In]n-KRAS2 PNA probes could be obtained, if stoichiometric amounts of 111InCl3 were used.

Radiohybridization Probe Stability in Vitro

These preparations were stable at 22 °C for more than 2 days, as determined by HPLC, and were stable to challenges with 100-fold molar excesses of diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), human serum albumin, or cysteine. The analyses indicated that essentially all of the 111In(III) was bound to DOTAn-KRAS2 PNA probes. These results made it possible to administer the labeled probes directly without the necessity for further purification. Due to the efficiency of labeling observed, each labeled probe was used directly for administration into the tail veins of immunocompromised mice bearing AsPC1 xenografts.

Radiohybridization Probe Stability in Vivo

To check the in vivo stability of radiohybridization probe, [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes were injected into the tail veins of immunocompromised mice bearing AsPC1 pancreatic cancer xenografts. HPLC analysis of radioactivity in the combined 3.5 h urine sample from mice injected with [111In]2KRAS2 G12D probe, WT5195 (Figure 1C) and [111In]16KRAS2 G12D probe, WT13842 (Figure 1D) revealed a void volume peak of free 111In that included less than 1% of radioactivity and a probe peak eluting at 9 min with more than 99% of the radioactivity.

Breakdown fragments of [111In]WT5195 and [111In]WT13842 were not detected. In a comparable study with [64Cu]DOTA-AEEA-CCND1 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 analogue in immunocompromised mice bearing breast cancer xenografts, no evidence was seen for transchelation to serum or tissue proteins (13).

Systemic Administration of Radiohybridization Probes

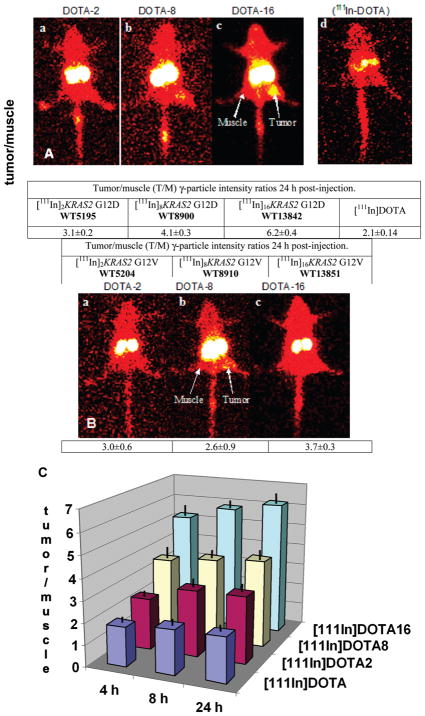

Scintigraphic images of γ-particles emitted from immunocompromised mice bearing pancreatic cancer xenografts 24 h after administration of [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes are shown in Figure 2A for the fully matched [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes and in Figure 2B for the single mismatch [111In]nKRAS2 G12 V probes. Imaging of PNA-free [111In]DOTA as a control is also presented in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

Scintigraphic images of immunocompromised mice bearing human AsPC1 pancreatic cancer xenografts at 24 h after tail vein administration of ~2 nmol (300–350 μCi, 11–13 MBq) of [111In]nKRAS2 probes to groups of 3 mice. (A) Fully matched G12D probe images (a) [111In]2KRAS2 G12D, WT5195; (b) [111In]8KRAS2 G12D, WT8900; (c) [111In]16KRAS2 G12D, WT13842; (d) 80 nmol [111In]DOTA (~11 MBq, ~300 μCi) control. Tumor/Muscle (T/M) γ-particle intensity ratios were calculated for each group of 3 mice. Holm-Sidak all pairwise multiple comparison revealed that each group was statistically significantly different from the others (p ≤ 0.05). (B) Single mismatch G12 V probes images (a) [111In]2KRAS2 G12 V, WT5204; (b) [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V, WT8910; (c) [111In]16KRAS2 G12 V, WT13851. Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks indicated that the three treatment groups were indistinguishable from each other. (C) Histograms of tumor/muscle (T/M) γ-particle intensity ratios of G12D fully matched probes calculated from scintigraphic image intensities. Solid black lines show standard deviations. Each group was statistically significantly different from the other three (p ≤ 0.05).

Digital scanning of the xenograft region-of-interest on the right flank vs the mirror image tumor-free region-of-interest on the left flank (muscle) was carried out to determine the tumor/ muscle (T/M) intensity ratios of each subject. The intensity averages and standard deviations of the T/M ratios are shown at the bottoms of each image in Figure 2 and in Table S1 in the Supporting Information.

In the case of imaging with fully matched [111In]nKRAS2 G12D PNA sequences, the T/M ratios increased from 3.1 ± 0.2 at n = 2, WT5195; to 4.1 ± 0.3 at n = 8, WT8900; to 6.2 ± 0.4 at n = 16, WT13842. Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks indicated that the differences in the mean values among the four treatment groups were greater than would be expected by chance (p < 0.001). Comparison of each treatment group with every other treatment group by the Holm-Sidak all-pairwise multiple comparison procedure revealed that each group was statistically significantly different from the others (p ≤ 0.05).

On the other hand, imaging with single mismatch [111In]n-KRAS2 G12 V PNA control probes showed lower T/M ratios (3.0 ± 0.6 at n = 2, WT5204; 2.6 ± 0.9 at n = 8, WT8910; and 3.7 ± 0.3 at n = 16, WT13851). Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance on ranks indicated that the three treatment groups were indistinguishable from each other. T/M ratios from single mismatch [111In]nKRAS2 G12 V control probes were comparable to the T/M ratios for the PNA-free [111In]DOTA control (Figure 2A). The single mismatch control results established a basis for determination of PNA sequence specificity for the accumulation of fully matched [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes in the xenografts.

Upon comparing the image intensity T/M ratios obtained for fully matched [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes in AsPC1 xenografts in mice (Figure 2C), it is apparent that the T/M ratio for [111In]2KRAS2 G12D remained at ~3 at 4, 8, and 24 h after injection, while T/M for [111In]8KRAS2 G12D remained at ~4, and T/M for [111In]16KRAS2 G12D remained at ~6. This result implies that the avidity of the xenografts for the [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes, relative to the avidity of the contralateral muscle, had already leveled out by 4 h after administration.

Dose Dependence of Radiohybridization Probe Administration

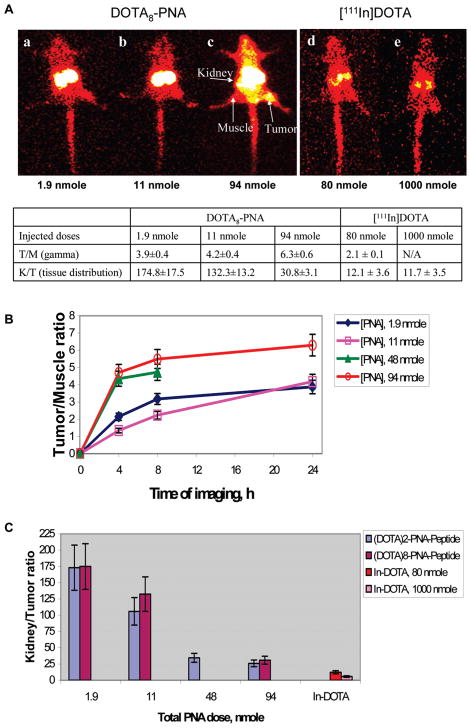

In view of our intent to use Gd(III)-chelated probes for MRI of mRNA expression (24), we assessed the effect of elevated doses of GdnKRAS2 G12 V probes with constant doses of [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probes on scintigraphic image intensity. Nonradioactive GdnKRAS2 G12 V probes (n = 2 or 8) (1.9, 11, 48, and 94 nmol) were mixed with ~2 nmol (300–350 μCi, 11–13 MBq) of fully matched [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probe, then administered to immunocompromised mice bearing CAPAN2 (G12 V) pancreatic cancer xenografts. Scintigraphic images recorded 24 h after administration of [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probes are shown in Figure 3A for added Gd8KRAS2 G12 V probe, WT8910, and in Figure S3 of the Supporting Information for Gd2KRAS2 G12 V probe, WT5204. Elevated doses of Gd8KRAS2 G12 V probes increased accumulation of the fully matched [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probe in CAPAN2 (G12 V) xenografts, thereby increasing the T/M ratio from 3.9 ± 0.4 to 6.3 ± 0.6 (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Immunocompromised mice bearing human CAPAN2 (G12 V) pancreatic cancer xenografts at 24 h after tail vein administration of ~2 nmol (300–350 μCi, 11–13 MBq) of fully matched [111In]8-KRAS2 G12 V, WT8910, mixed with increasing doses of Gd2-KRAS2 G12 V, WT5512, or Gd8-KRAS2 G12 V, WT10144. (A) Scintigraphic images of mice that received (a) 1.9 nmol, (b) 11 nmol, or (c) 94 nmol of nonradioactive Gd8 probes. Additional tumor-bearing mice were injected with (d) 80 nmol (~11 MBq, ~300 μCi) or (e) 1000 nmol (~11 MBq, ~300 μCi) of [111In]DOTA as controls. Tumor/Muscle (T/M) ratios were calculated from γ-particle intensity data. Kidney/Tumor (K/T) ratios were calculated from tissue distribution data. (B) Time course of Tumor/Muscle (T/M) ratios from γ-particle intensity data. (C) Dependence of kidney/tumor (K/T) tissue distribution ratios on elevated Gdn probe dose. The decrease of K/T with added nonradioactive Gdn probes were the same for Gd2 probes or Gd8 probes. The Mann–Whitney rank sum test indicated that there was not a statistically significant difference (p = 0.886).

The time courses of [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probe accumulation in tumor and muscle were similar for 1.9 and 11 additional nanomoles of nonradioactive probe, but shifted up markedly for 48 and 94 additional nanomoles (Figure 3B). The effect of additional nonradioactive probe was apparent as early as 4 h after administration. Tissue distribution data for all time points are shown in Table S2 in Supporting Information.

Tissue Distribution of Radiohybridization Probes

Tissue distribution of each of the [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes in immunocompromised mice bearing human AsPC1 pancreatic cancer xenografts was measured at 24 h after administration. The measured tissue distribution data are presented in Table 2. Tissue distribution data for [111In]nKRAS2 G12 V probes in CAPAN2 xenografts are presented in Table S2 in the Supporting Information. Probe distribution into the mouse pancreas was not measured, because it is wrapped around the intestine in a thin layer, unlike the human pancreas.

Table 2.

Tissue Distribution (% injected dose/g) of [111In]nKRAS2 PNA Probes vs [111In]DOTA, in Immunocompromised Mice Bearing Human AsPC1 (G12D) Pancreatic Cancer Xenograftsa

| A. Fully Matched [111In]nKRAS2 G12D Probes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tissues | [111In]2 WT5195 | null prob. | [111In]8 WT8900 | null prob. | [111In]16 WT13842 | null prob. | [111In]DOTA |

| muscle | 0.038 ± 0.007 | 0.0034 | 0.040 ± 0.010 | 0.0125 | 0.267 ± 0.052 | 0.0009 | 0.012 ± 0.003 |

| intestine | 0.048 ± 0.007 | 0.0025 | 0.048 ± 0.004 | 0.0004 | 0.201 ± 0.041 | 0.0014 | 0.018 ± 0.003 |

| heart | 0.028 ± 0.008 | 0.0150 | 0.035 ± 0.005 | 0.0013 | 0.189 ± 0.047 | 0.0019 | 0.008 ± 0.002 |

| lungs | 0.217 ± 0.257 | 0.2951 | 0.096 ± 0.021 | 0.0122 | 0.175 ± 0.048 | 0.0076 | 0.038 ± 0.009 |

| blood | 0.020 ± 0.010 | 0.2988 | 0.018 ± 0.001 | 0.0517 | 0.042 ± 0.007 | 0.0110 | 0.013 ± 0.003 |

| spleen | 0.079 ± 0.006 | 0.0003 | 0.075 ± 0.005 | 0.0002 | 0.279 ± 0.037 | 0.0004 | 0.032 ± 0.003 |

| kidneys | 18.367 ± 1.892 | 0.0001 | 29.615 ± 9.207 | 0.0054 | 42.609 ± 7.619 | 0.0007 | 0.500 ± 0.099 |

| liver | 0.147 ± 0.015 | 0.0005 | 0.152 ± 0.012 | 0.0002 | 0.584 ± 0.063 | 0.0001 | 0.055 ± 0.005 |

| tumor | 0.135 ± 0.034 | 0.0093 | 0.143 ± 0.011 | 0.0001 | 0.676 ± 0.030 | 0.000005 | 0.041 ± 0.005 |

| total % | 19.08 ± 1.91 | 0.0001 | 30.22 ± 9.19 | 0.0124 | 45.02 ± 7.62 | 0.0001 | 0.72 ± 0.14 |

| T/M | 3.59 ± 0.95 | 0.8015 | 3.72 ± 0.66 | 0.5985 | 2.6 ± 0.56 | 0.2091 | 3.40 ± 0.74 |

| T/B | 7.12 ± 1.59 | 0.0145 | 7.8 ± 0.64 | 0.0005 | 16.39 ± 1.96 | 0.0003 | 3.18 ± 0.45 |

| K/T | 142.67 ± 41.47 | 0.0056 | 210.8 ± 79.68 | 0.0048 | 63.43 ± 14.42 | 0.0048 | 12.12 ± 3.62 |

|

| |||||||

| B. Single Mismatch [111In]nKRAS2 G12 V Probes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| tissues | [111In]2 WT5204 | null prob. | [111In]8 WT8910 | null prob. | [111In]16 WT13851 | null prob. | [111In]DOTA |

| muscle | 0.046 ± 0.006 | 0.0009 | 0.030 ± 0.004 | 0.0034 | 0.201 ± 0.030 | 0.0004 | 0.012 ± 0.003 |

| intestine | 0.079 ± 0.008 | 0.0002 | 0.043 ± 0.006 | 0.0030 | 0.156 ± 0.023 | 0.0005 | 0.018 ± 0.003 |

| heart | 0.042 ± 0.004 | 0.0002 | 0.037 ± 0.006 | 0.0014 | 0.333 ± 0.042 | 0.0002 | 0.008 ± 0.002 |

| lungs | 0.093 ± 0.009 | 0.0017 | 0.207 ± 0.031 | 0.0008 | 0.371 ± 0.055 | 0.0005 | 0.038 ± 0.009 |

| blood | 0.049 ± 0.005 | 0.0004 | 0.012 ± 0.002 | 0.6560 | 0.213 ± 0.032 | 0.0004 | 0.013 ± 0.003 |

| spleen | 0.105 ± 0.012 | 0.0005 | 0.056 ± 0.009 | 0.0119 | 0.559 ± 0.087 | 0.0005 | 0.032 ± 0.003 |

| kidneys | 19.04 ± 2.34 | 0.0002 | 13.89 ± 2.11 | 0.0004 | 55.41 ± 12.85 | 0.0018 | 0.500 ± 0.099 |

| liver | 0.248 ± 0.033 | 0.0006 | 0.104 ± 0.015 | 0.0058 | 0.979 ± 0.150 | 0.0004 | 0.055 ± 0.005 |

| tumor | 0.144 ± 0.014 | 0.0003 | 0.113 ± 0.014 | 0.0011 | 1.309 ± 0.211 | 0.0005 | 0.041 ± 0.005 |

| total % | 19.85 ± 3.22 | 0.00006 | 14.5 ± 2.18 | 0.0004 | 59.53 ± 10.32 | 0.0109 | 0.72 ± 0.14 |

| T/M | 3.11 ± 0.46 | 0.5952 | 3.72 ± 0.007 | 0.4955 | 6.51 ± 0.97 | 0.0115 | 3.40 ± 0.74 |

| T/B | 2.96 ± 0.45 | 0.5816 | 9.28 ± 0.007 | 0.00002 | 6.15 ± 0.88 | 0.0065 | 3.18 ± 0.45 |

| K/T | 132.2 ± 26.1 | 0.0014 | 122.8 ± 35.2 | 0.0056 | 42.3 ± 8.4 | 0.0046 | 12.12 ± 3.62 |

Tissue samples were analyzed 24 h after tail vein administration of ~2 nmol doses of each [111In]nKRAS2 probe, or 80 nmol (~11 MBq, 300 μCi) of [111In]DOTA control, to immunocompromised mice bearing human AsPC1 (G12D) pancreatic cancer xenografts (n = 3).

In addition to typical measurements of percent of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) for individual tissues, we calculated the total percent of injected dose per gram of tissue. The total percent of injected dose per gram of tissue informs us of the total radioactivity that remains in the body after injection. That number reports how quickly the radioactive probes can be utilized or excreted. Interestingly, we found that this value, total percent of injected dose per gram of tissue, is different for different generations of dendrimers and different kinds of radioactive probes.

At 24 h after injection, the total %ID/g increased in all tissues with the size of the dendrimer and number of 111In per probe, which implies that larger probes are retained longer in the tissues prior to renal excretion. This phenomenon was seen with both the fully matched [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes (Table 2A) and with the single mismatch [111In]nKRAS2 G12 V probes (Table 2B). Tumor %ID also increased with dendrimer size, particularly for n = 16 (Table 2A). The muscle %ID also increased in the same order, which correlates with little change in the tumor/ muscle (T/M) ratios as a function of n (Table 2A). On the other hand, the kidney/tumor ratios (K/T) were least for n = 16 (Table 2AB).

In contrast, the total %ID/g for the PNA-free [111In]DOTA control was 26–83 times less than the total %ID/g for the [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes (Table 2A), which implies that the low molecular mass [111In]DOTA does not accumulate readily in tissues, unlike the significant nonspecific organ accumulation of free 111In(III) (25), and is cleared much more rapidly than high molecular weight probes like [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes. The [111In]DOTA complex does not dissociate appreciably over the time course of the experiment, precluding redistribution to naturally occurring proteins in blood and tissues. As a result, the chemically stable and neutral [111In]DOTA complex exits the body quickly by renal excretion. The T/M ratios for [111In]DOTA were comparable to that for [111In]nKRAS2 PNA probes (Table 2).

Elevated doses of nonradioactive Gd8-KRAS2 G12 V probe, 1.9 to 94 nmol, added to [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probe, increased image intensity of the fully matched [111In]8PNA probe in CAPAN2 (G12 V) xenografts 24 h after administration (Figure 3A). As a result, T/M ratios of 111In image intensity at 24 h increased from 3.9 ± 0.4 to 6.3 ± 0.6 (Figure 3A). T/M ratios for all time points increased upon addition of Gd2,8-KRAS2 G12 V probes (Figure 3B, and Table S2 in Supporting Information).

Tissue distribution measurements (Table S2 in Supporting Information) showed increased accumulation of the fully matched [111In]8PNA probe, in combination with elevated doses of nonradioactive Gd2,8-KRAS2 G12 V probe in CAPAN2 (G12 V) xenografts, as well as in other tissues, by 3–6-fold, except for a 2-fold decrease in kidney accumulation. The K/T ratio decreased dramatically and significantly, more than 5-fold, from 174 ± 17 to 28 ± 3, 24 h after coinjecting 94 nmol of nonradioactive Gd2,8-KRAS2 G12 V probe with 2 nmol of [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probe (Figure 3C). K/T reduction by the Gd2-KRAS2 G12 V probe vs the Gd8-KRAS2 G12 V probe, analyzed by the Mann–Whitney rank sum test, was not significantly different (p = 0.886).

DISCUSSION

These studies revealed that [111In]nKRAS2 PNA-IGF1 analogue nanoparticles permeated xenografts, entered cancer cells, and accumulated in a sequence-specific manner. We observed that the relative T/M intensity of scintigraphic images of AsPC1 pancreatic cancer xenografts increased with the size of the dendrimer and the number of DOTA chelating groups, up to n = 16, but only for fully matched [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes. In contrast, the relative T/M intensity of scintigraphic images of AsPC1 pancreatic cancer xenografts stayed constant for single mismatch [111In]nKRAS2 G12 V probes, independent of size and number of chelated 111In cations.

Tissue distribution measurements of total %ID/g, reaching 45–60%, imply that the largest [111In]16KRAS2 PNA probes exhibit longer clearance times than the smaller probes. In the n = 16 case, renal excretion was apparently reduced, relative to smaller probes. That hypothesis agrees with the reduction in K/T ratios with increasing “n” of DOTA residues per PNA probe. For MRI, as well as for scintigraphic imaging, extended retention will increase signal intensity over 24–48 h, for which we already observed a preliminary indication (24).

The average diameter of gyration for the Gd16-KRAS2 G12D probe, g/mol, was previously calculated to be 3.3 ± 0.1 nm (24). In contrast, the single chelator [64Cu]KRAS2 G12D probe, g/mol, was previously calculated to be 2.2 ± 0.1 nm (12). On the nanoparticle scale, 2–3 nm is still small, minimizing the probability of nanoparticle toxicity. DOTA holds Gd(III) so strongly (35) that toxicity by transchelation is most unlikely. In practice, Gd-chelator toxicity occurs only in the context of poor kidney function (36). Considering potential toxicity of the PNA, no hepatic or renal toxicity was observed in mice after administration of 2.5 mg/kg of PNA (37), nor immunogenicity (38), mutagenicity, or clastogenicity (39).

In our previous report (24), we noted that concentration of KRAS2 PNA hybridization probes in AsPC1 cells should approach a maximum, based on our QRT-PCR analysis (12), of 2 × 104 KRAS2 mRNAs in a 1 pL pancreas cancer cell, or ~30 nM. At 1 111In(III) or Gd(III) per DOTA chelator, 480 nM intracellular 111In(III) or Gd(III) might thus be achieved at 16 Gd(III) per probe. These calculated concentrations of intracellular Gd(III) are in accord with the minimum concentration of 300 nM Gd-nanoparticle calculated for molecular MR visualization in T1-weighted imaging (40). That estimate was confirmed in turn for fourth-generation polyamidoamine dendrimers conjugated with 40 Gd(III)-DTPA chelators and a fluorescently labeled anti-EGFR antibody. That large, slowly rotating probe displayed a relaxivity of 323.5/mM ·s (40). Furthermore, we discussed at length (24) the phenomena of restricted mobility and degrees of freedom for Gdn-KRAS2 PNA probes bound to high molecular mass KRAS2 mRNA/polyribosome complexes in viscous cytoplasm that would all contribute to increased relaxivity, relative to Gd-DTPA. This analysis predicts favorable tumor accumulation of the Gd8-chelated KRAS2 probe at elevated doses, which correlates with the positive preliminary MRI result we reported earlier (24).

After finding sequence-specific images of KRAS2 mRNA expression in pancreatic cancer xenografts with 2 nmol doses of complementary [111In]nKRAS2 G12D probes, we modeled the circumstances of MRI, requiring higher doses of nonradioactive Gd-chelated probes. Upon mixing increasing doses of Gdn-KRAS2 G12 V probe with constant [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probe prior to administration, we observed more intense CAPAN2 G12 V xenograft 111In images, and less intense kidney images, as the nonradioactive Gdn-KRAS2 G12 V probe dose increased. In parallel, elevated doses of Gd2.8-KRAS2 G12 V probe added to [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probe significantly decreased K/T.

This phenomenon suggests that nonspecific binding sites in the kidney consume a significant portion of the 2 nmol doses of undiluted [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probes, but only a small portion of the 96 nmol doses of the [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V-Gdn-KRAS2 G12 V mixture. In the AsPC1 xenograft, however, IGF1R turns over continuously over the 48 h of these experiments, continually delivering probes with IGF1 analogues into the cytoplasm of AsPC1 cells. Furthermore, continuous transcription of new KRAS2 mRNAs over the 48 h of these experiments suggests that available KRAS2 mRNA binding sites are not saturated. If the intracellular KRAS2 mRNAs are not saturated, then both labeled and unlabeled PNA probes can accumulate inside pancreatic cancer cells over time, yielding our observation of significantly decreased K/T at 24–48 h.

CONCLUSIONS

(1) mRNA expression in pancreatic cancer xenografts can be selectively imaged with ([111In]DOTA-AEEA)n-PDAPm-AEEA2-KRAS2 PNA-AEEA-IGF1 analogue probes with single mismatch specificity. (2) Tumor/Muscle image intensity ratios for ([111In]DOTA)nKRAS2 G12D PNA probes increased from 3 to 6, in the order DOTA2 < DOTA8 < DOTA16. (3) Elevated doses of Gd8-KRAS2 G12 V probes increased the image intensity of [111In]8KRAS2 G12 V probes in xenografts, thereby increasing the tumor-to-muscle ratios from 3.9 ± 0.4 to 6.3 ± 0.6. Elevated doses of Gd2,8-KRAS2 G12 V probes decreased the kidney-to-tumor ratios more than 5-fold from 174 ± 17 to 28 ± 3.

These experiments supported the hypothesis that PDAP dendrimers with up to 16 DOTA chelators coupled to PNA-IGF1 analogue probes do not inhibit tumor uptake of PNA-IGF1 analogue probes. Thus, dendrimeric PNA genetic imaging agents can be used directly for preclinical scintigraphic imaging. In addition, dendrimeric PNA genetic imaging agents can be used for preliminary radionuclide testing of targeting specificity prior to full preclinical development of Gd-chelated PNA agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of pathogenic mRNA in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Richard Wassell for assistance in measuring mass spectra of DOTA-PDAP-PNA-IGF1 analogues. Grant support: This work was supported in part by NCI contract N01 CO27175 and NCI subaward CA105008 to E.W., and NCI grant CA109231 to M.L.T. Conflicts of interest: E.W. and MLT founded GeneSeen LLC, which might ultimately benefit from the results of this investigation, but did not support the work.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AEEA, aminoethoxyethoxyacetate linker; DAP, diamidopropanoyl; DOTA, 1,4,7,10-tetra(carboxymethylaza)cy-clododecane; HATU, 2-(7-aza-1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetra-methyl-uronium hexa-fluorophosphate; PDAP, polydiamidopropanoyl; PET, positron emission tomography; PNA, peptide nucleic acid; SBTG, S-benzoyl-thioglycoloyl; Tm, melting temperature.

Supporting Information Available: Additional data on synthesis and experimental results with additional KRAS2 probes. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kern SE, Hruban RH, Hidalgo M, Yeo CJ. An introduction to pancreatic adenocarcinoma genetics, pathology and therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:607–13. doi: 10.4161/cbt.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes Dev. 2003;17:545–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.1047403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavitian B, Terrazzino S, Kuhnast B, Marzabal S, Stettler O, Dolle F, Deverre JR, Jobert A, Hinnen F, Bendriem B, Crouzel C, Di Giamberardino L. In vivo imaging of oligonucleotides with positron emission tomography. Nat Med. 1998;4:467–71. doi: 10.1038/nm0498-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi N, Boado RJ, Pardridge WM. Antisense imaging of gene expression in the brain in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14709–14714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250332397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallazzi F, Wang Y, Jia F, Shenoy N, Landon LA, Hannink M, Lever SZ, Lewis MR. Synthesis of radiometal-labeled and fluorescent cell-permeating peptide-PNA conjugates for targeting the bcl-2 proto-oncogene. Bioconjugate Chem. 2003;14:1083–95. doi: 10.1021/bc034084n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasberg RG. Molecular imaging and cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:335–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roivainen A, Tolvanen T, Salomaki S, Lendvai G, Velikyan I, Numminen P, Valila M, Sipila H, Bergstrom M, Harkonen P, Lonnberg H, Langstrom B. 68Ga-labeled oligonucleotides for in vivo imaging with PET. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:347–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian X, Aruva MR, Qin W, Zhu W, Duffy KT, Sauter ER, Thakur ML, Wickstrom E. External imaging of CCND1 cancer gene activity in experimental human breast cancer xenografts with 99mTc-peptide-peptide nucleic acid-peptide chimeras. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:2070–2082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian X, Aruva MR, Qin W, Zhu W, Sauter ER, Thakur ML, Wickstrom E. Noninvasive molecular imaging of MYC mRNA expression in human breast cancer xenografts with a [99mTc]peptide-peptide nucleic acid-peptide chimera. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:70–79. doi: 10.1021/bc0497923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun X, Fang H, Li X, Rossin R, Welch MJ, Taylor JS. MicroPET imaging of MCF-7 tumors in mice via unr mRNA-targeted peptide nucleic acids. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:294–305. doi: 10.1021/bc049783u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakrabarti A, Zhang K, Aruva MR, Cardi CA, Opitz AW, Wagner NJ, Thakur ML, Wickstrom E. Radiohybridization PET imaging of KRAS G12D mRNA expression in human pancreas cancer xenografts with [64Cu]DO3A-peptide nucleic acid-peptide nanoparticles. Cancer Biol, Ther. 2007;6:948–956. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.6.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian X, Aruva MR, Zhang K, Cardi CA, Thakur ML, Wickstrom E. PET imaging of CCND1 mRNA in human MCF7 estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer xenografts with an oncogene-specific [64Cu]DO3A-PNA-peptide radiohybridization probe. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1699–1707. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.042499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia F, Figueroa SD, Gallazzi F, Balaji BS, Hannink M, Lever SZ, Hoffman TJ, Lewis MR. Molecular imaging of bcl-2 expression in small lymphocytic lymphoma using 111In-labeled PNA-peptide conjugates. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:430–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen PE, Egholm M, Berg RH, Buchardt O. Sequence-selective recognition of DNA by strand displacement with a thymine-substituted polyamide. Science. 1991;254:1497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1962210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen HJ, Bentin T, Nielsen PE. Antisense properties of peptide nucleic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1489:159–66. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray GD, Basu S, Wickstrom E. Transformed and immortalized cellular uptake of oligodeoxynucleoside phosphorothioates, 3′-alkylamino oligodeoxynucleotides, 2′-O-methyl oligoribonucleotides, oligodeoxynucleoside methylphosphonates, and peptide nucleic acids. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:1465–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)82440-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basu S, Wickstrom E. Synthesis and characterization of a peptide nucleic acid conjugated to a D-peptide analog of insulin-like growth factor 1 for increased cellular uptake. Bioconjugate Chem. 1997;8:481–488. doi: 10.1021/bc9700650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egholm M, Buchardt O, Christensen L, Behrens C, Freier SM, Driver DA, Berg RH, Kim SK, Norden B, Nielsen PE. PNA hybridizes to complementary oligo-nucleotides obeying the Watson- Crick hydrogen-bonding rules. Nature. 1993;365:566–568. doi: 10.1038/365566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian X, Wickstrom E. Continuous solid-phase synthesis and disulfide cyclization of peptide-PNA-peptide chimeras. Org Lett. 2002;4:4013–4016. doi: 10.1021/ol026676b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian X, Chakrabarti A, Amirkhanov NV, Aruva MR, Zhang K, Mathew B, Cardi C, Qin W, Sauter ER, Thakur ML, Wickstrom E. External imaging of CCND1, MYC, and KRAS oncogene mRNAs with tumor-targeted radio-nuclide-PNA-peptide chimeras. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1059:106–44. doi: 10.1196/annals.1339.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opitz AW. Chemical Engineering. University of Delaware; Newark: 2008. p. 457. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amirkhanov NV, Wickstrom E. Synthesis of novel polydiamidopropanoate dendrimer PNA-peptide chimeras for non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging of cancer. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2005;24:423–6. doi: 10.1081/ncn-200059955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amirkhanov NV, Dimitrov I, Opitz AW, Zhang K, Lackey JP, Cardi CA, Lai S, Wagner NJ, Thakur ML, Wickstrom E. Design of (Gd-DO3A)n-polydiami-dopropanoate-peptide nucleic acid-D(Cys-Ser-Lys-Cys) magnetic resonance contrast agents. Biopolymers. 2008;89:1061–1076. doi: 10.1002/bip.21059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe N, Oriuchi N, Endo K, Inoue T, Tanada S, Murata H, Kim EE, Sasaki Y. Localization of indium-111 in human malignant tumor xenografts and control by chelators. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:853–8. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole WC, DeNardo SJ, Meares CF, McCall MJ, DeNardo GL, Epstein AL, O’Brien HA, Moi MK. Comparative serum stability of radiochelates for antibody radiopharmaceuticals. J Nucl Med. 1987;28:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pippin CG, Parker TA, McMurry TJ, Brechbiel MW. Spectrophotometric method for the determination of a bifunctional DTPA ligand in DTPA-monoclonal antibody conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 1992;3:342–5. doi: 10.1021/bc00016a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryant LH, Jr, Brechbiel MW, Wu C, Bulte JW, Herynek V, Frank JA. Synthesis and relaxometry of high-generation (G = 5, 7, 9, and 10) PAMAM dendrimer-DOTA-gadolinium chelates. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:348–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199902)9:2<348::aid-jmri30>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan MH, Chu TM. Characterization of the tumorigenic and metastatic properties of a human pancreatic tumor cell line (AsPC-1) implanted orthotopically into nude mice. Tumour Biol. 1985;6:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasuda D, Iguchi H, Ikeda Y, Nishimura S, Steeg P, Misawa T, Nasawa H, Kono A. Possible association of nm23 gene expression and Ki-ras point mutations with metastatic potential in human pancreatic cancer-derived cell lines. Int J Oncol. 1993;3:641–4. doi: 10.3892/ijo.3.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neid M, Datta K, Stephan S, Khanna I, Pal S, Shaw L, White M, Mukhopadhyay D. Role of insulin receptor substrates and protein kinase C-zeta in vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor expression in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:3941–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fogh J, Fogh JM, Orfeo T. One hundred and twenty-seven cultured human tumor cell lines producing tumors in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;59:221–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun C, Yamato T, Furukawa T, Ohnishi Y, Kijima H, Horii A. Characterization of the mutations of the K-ras, p53, p16, and SMAD4 genes in 15 human pancreatic cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:89–92. doi: 10.3892/or.8.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yendluri V, Wright JR, Coppola D, Buck E, Iwata KK, Mokenze M, Sebti S, Springett GM. Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium. American Society of Clinical Oncology; Orlando, FL: 2008. p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tweedle MF, Hagan JJ, Kumar K, Mantha S, Chang CA. Reaction of gadolinium chelates with endogenously available ions. Mag Reson Imaging. 1991;9:409–415. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(91)90429-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Briguori C, Colombo A, Airoldi F, Melzi G, Michev I, Carlino M, Montorfano M, Chieffo A, Bellanca R, Ricciardelli B. Gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrotoxicity in patients undergoing coronary artery procedures. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:175–80. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rembach A, Turner BJ, Bruce S, Cheah IK, Scott RL, Lopes EC, Zagami CJ, Beart PM, Cheung NS, Langford SJ, Cheema SS. Antisense peptide nucleic acid targeting GluR3 delays disease onset and progression in the SOD1 G93A mouse model of familial ALS. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:573–82. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cutrona G, Boffa LC, Mariani MR, Matis S, Damonte G, Millo E, Roncella S, Ferrarini M. The peptide nucleic acid targeted to a regulatory sequence of the translocated c-myc oncogene in Burkitt’s lymphoma lacks immunogenicity: follow-up characterization of PNAEmu-NLS. Oligonucleotides. 2007;17:146–50. doi: 10.1089/oli.2007.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boffa LC, Cutrona G, Cilli M, Matis S, Damonte G, Mariani MR, Millo E, Moroni M, Roncella S, Fedeli F, Ferrarini M. Inhibition of Burkitt’s lymphoma cells growth in SCID mice by a PNA specific for a regulatory sequence of the translocated c-myc. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:220–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang E, Isaacman S, Chang Y-T, Deans A, Johnson G, Canary J. Radiological Society of North America Annual Meeting; Chicago IL. 2005. p. TA35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.