Abstract

Introduction

In the brain, the chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor 1 (1CX3CR1) gene is expressed only by microglia, where it acts as a key mediator of the neuron–microglia interactions. We assessed whether the 2 common polymorphisms of the CX3CR1 gene (V249I and T280M) modify amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) phenotype.

Methods

The study included 755 ALS patients diagnosed in Piemonte between 2007 and 2012 and 369 age-matched and sex-matched controls, all genotyped with the same chips.

Results

Neither of the variants was associated with an increased risk of ALS. Patients with the V249I V/V genotype had a 6-month-shorter survival than those with I/I or V/I genotypes (dominant model, P = 0.018). The T280M genotype showed a significant difference among the 3 genotypes (additive model, P = 0.036). Cox multivariable analysis confirmed these findings.

Discussion

We found that common variants of the CX3CR1 gene influence ALS survival. Our data provide further evidence for the role of neuroinflammation in ALS.

Keywords: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, CX3CR1 gene, survival, microglia, neurodegeneration

The pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) remains largely unknown.1 Recently, neuroinflammation has come under increasing study, particularly with regard to the propagation of the disease. Microglia are a central protagonist of the neuroinflammatory component of neurodegeneration in ALS. There are indications that microglia have a dual effect on the course of ALS. Initially, microglia in the form of alternatively activated M2 cellular phenotype have neuroprotective functions, but, in the chronic phase, microglia have distinctly toxic functions (classically activated M1 phenotype).2

The chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor 1 (CX3CR1) gene, also known as fractalkine receptor (OMIM: 601470), is expressed by macrophage populations in systemic tissues,3,4 whereas it is expressed only by microglia in the brain,5 where it is a key mediator of the neuron–microglia interactions that are upregulated in many inflammatory conditions.6,7 The CX3CR1 gene has 2 main functional variants (V249I, rs3732379 and T280M, rs3732378),8,9 both of which impair the activity of the CX3CR1 protein and have been associated with several inflammatory diseases, including multiple sclerosis,10 age-related macular degeneration,11 and coronary artery disease.12 Recently, it was reported that the p.V249I and p.T280M polymorphisms of the CX3CR1 gene may modify ALS phenotype.13 A study of 187 ALS patients and 378 control participants recruited at an ALS clinic in Barcelona, Spain found that patients homozygous for valine at the 249 amino acid of CX3CR1 (V249I V/V) had a 25-month-longer survival.13 The current study assesses whether the 2 common polymorphisms of the CX3CR1 gene, V249I and T280M, alter the risk of developing ALS and/or modify phenotype in a large population-based series of ALS patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study includes ALS patients diagnosed in Piemonte, Italy, between 2007 and 2012 and healthy age-matched and gender-matched controls from the same geographic area. ALS patients were recruited through the Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta Register for ALS (PARALS), a prospective epidemiologic registry involving all the neurological departments of the 2 regions of Northern Italy. Epidemiological data regarding the 1995–2004 period have been published elsewhere.14 Both familial and apparently sporadic ALS patients were included in the present study. Patients with definite, probable, and probable laboratory-supported ALS by El Escorial revised criteria15 were included in the registry. The 369 control participants were identified through the patients’ general practitioners (population-based controls).

Genotyping

ALS cases and controls were genotyped by using Illumina Infinium II HumanHap550 SNP chips (Illumina, San Diego, CA), which assayed 555,352 common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome.16 Quality control parameters for genotype calling and filtering were as previously described.17 Genotype data for V249I (rs3732379; build hg19, chr3:39307256C>T) and T280M (rs3732378; chr3:39307162G>A) were extracted from the larger data set. SNP genotypes were not confirmed on another platform, such as Sanger sequencing. However, the quality of genotyping has been assessed with polar and Cartesian cluster plots for SNPs V249I (rs3732378) and T280M (rs3732379). The quality control metric of genotyping accuracy (GenTrain score) for this SNP was 0.835, indicating a high level of precision in assigning genotypes to samples (Supporting Information Fig. 1). GenTrain score is a proprietary score instituted by Illumina to evaluate SNP calls. It ranges from 0.0 to 1.0 and, by convention, SNPs with scores greater than 0.4 are considered to be accurate. ALS patients were also tested for superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1; all exons), TAR DNA binding protein (TARDBP; only exon 6 sequenced), fused in sarcoma (FUS; exons 14 and 15), angiogenin (ANG), and chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9ORF72) by using methodology described elsewhere.18

Statistical Analysis

Two-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the association between the polymorphisms and site of onset. Student’s t test or ANOVA was used to assess the effect of polymorphisms on age at onset. Pooled odds ratios were calculated for the association between ALS and the 2 polymorphisms according to the dominant, recessive, heterozygote, homozygote, and allelic models. The effect of the 2 polymorphisms on survival was analyzed according to dominant, recessive, and additive models. Survival was calculated from onset to death, tracheostomy, or censoring date (December 31, 2015) with the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by using the log–rank test. No patients were lost to follow-up. Multivariable analysis was performed with the Cox proportional hazards model (stepwise backward), with a retention criterion of P < 0.1. Significance level was set at P < 0.05 after correction for multiple models. Reported P values are those after correction. Data were processed in SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Sample Size

Sample size and statistical power were calculated in Quanto software (http://biostats.usc.edu/Quanto.html).19 This study has a priori statistical power of 80% (α = 5%) for detecting a difference of 5 months in survival between groups of patients (main population survival, 33.5 ± 29.3 months; minor allele frequency, 0.25), and a β of 98% (α = 5%) for detecting a difference of 5 months.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Città della Salute e della Scienza of Torino ethical committee. All patients and controls signed written informed consent. Databases were treated according to Italian privacy regulations.

RESULTS

This study included 755 ALS patients and 369 controls. The demographic and clinical characteristics of cases and controls are presented in Table 1, and the distribution of CX3CR1 genotypes among cases and controls is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cases and controls

| Factor | ALS cases (n = 755) | Healthy controls (n = 369) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at onset (years, SD) | 63.7 (11.1) | 63.5 (10.9) | 0.76 |

| Women (%) | 357 (47.3) | 177 (48.0) | 0.93 |

| Site of onset bulbar (%) | 226 (29.9) | na | na |

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; na, not applicable.

Table 2.

Genotypes of CX3CR1 gene polymorphisms V249I and T280M in ALS cases and healthy controls

| SNP | Genotype | Hardy-Weinberg (P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V249I | V/V | V/I | I/I | |

| Cases* (n) | 387 | 305 | 63 | 0.79 |

| Controls* (n) | 206 | 133 | 27 | 0.39 |

| T280M | T/T | T/M | M/M | |

| Cases† (n) | 558 | 175 | 22 | 0.07 |

| Controls† (n) | 281 | 77 | 8 | 0.19 |

SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

P = 0.295, cases vs. controls.

P = 0.561, cases vs. controls.

Risk of ALS and Age at Onset and Site of Onset

Neither V249I nor T280M variants were associated with increased risk of disease under any of the tested statistical models (Supporting Information Table 1). Age at onset and site of onset of ALS were not influenced by either the V249I variant or the T280M variant under any of the considered statistical models (Supporting Information Table 2).

CX3CR1 Genotypes and Survival

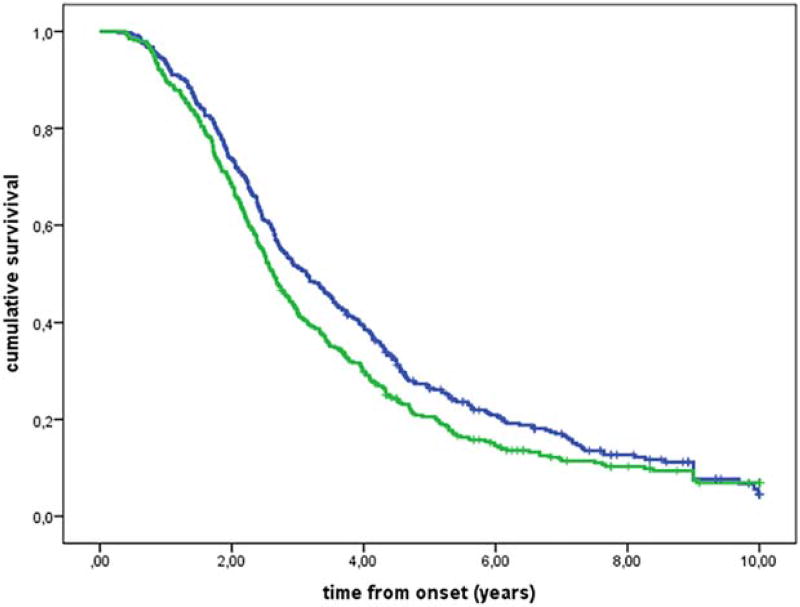

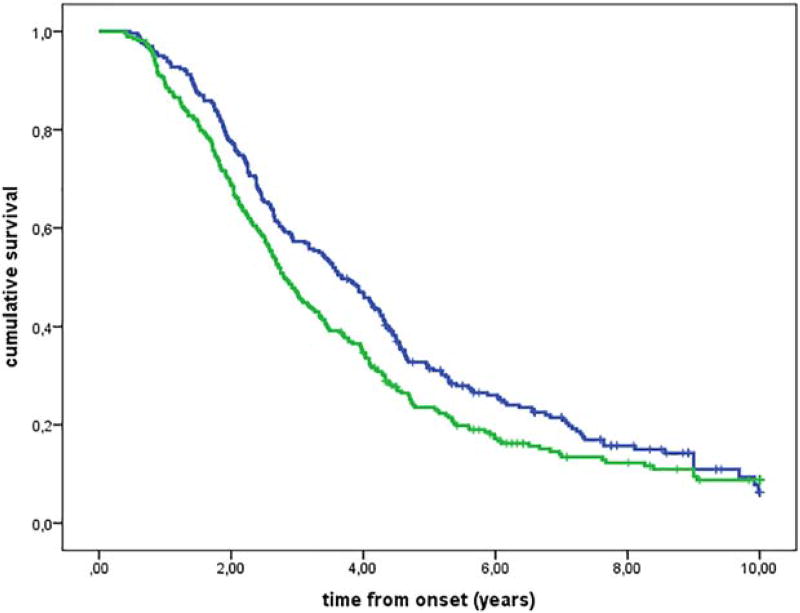

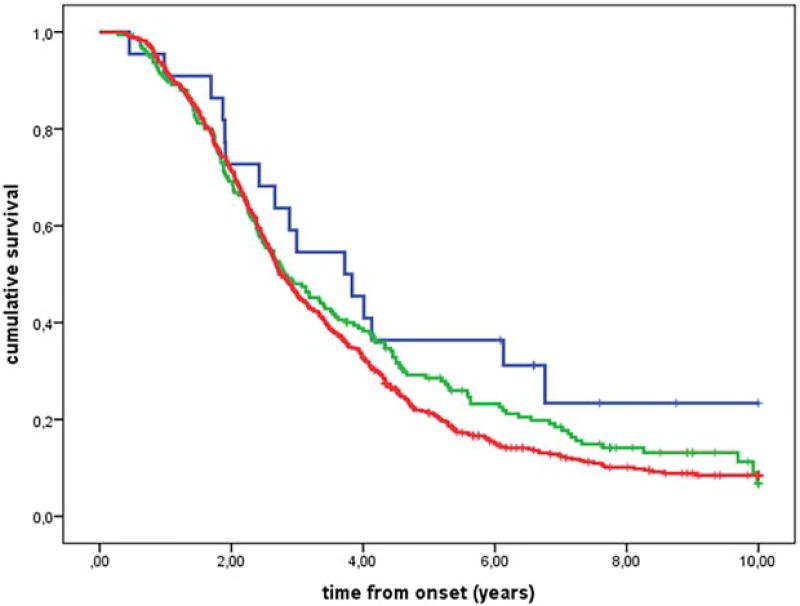

We found that survival was 6 months shorter in patients who were homozygous for valine at the 249 amino acid of CX3CR1 (V249I VV genotype) compared with those with V249I I/I and V249I V/I genotypes (Fig. 1, Supporting Information Table 1). No differences in survival were observed in familial ALS patients (P = 0.95) or in patients with bulbar onset (P = 0.96). In contrast, there was an 11-month difference in survival among patients with spinal onset carrying the V249I V/V genotype (V249I V/V genotype median survival time 2.8 years, interquartile range [IQR] 1.8–4.7 years; V249I I/I and V249I V/I genotype median survival time 3.7 years, IQR 2.1–6.1 years; Fig. 2). The T280M genotype was associated with a significant difference in survival under the additive model (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for CX3CR1 V249I genotypes according to a dominant model (P = 0.018). Genotypes VI + II (368 cases; blue line) and genotype VV (387 cases; green line).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for CX3CR1 V249I genotypes according to a dominant model in patients with spinal onset (P = 0.016). Genotypes VI + II (262 cases; blue line) and genotype VV (268 cases; green line).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for CX3CR1 T280M genotypes according to an additive genetic model (P = 0.036, χ2 for trend test). Genotype MM (22 cases; blue line), genotype TM (175 cases; green line), and genotype TT (558 cases; red line).

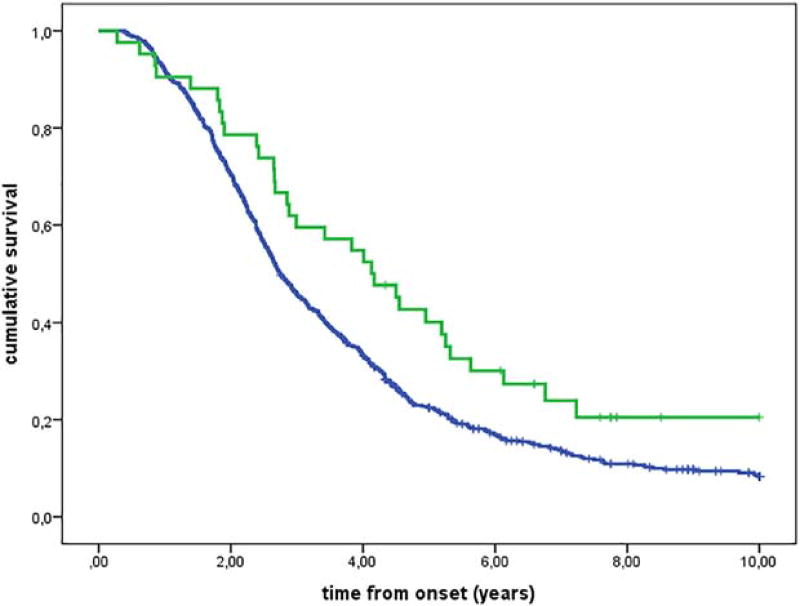

Because the presence of the minor allele for the 2 tested SNPs (249I and 280M) was associated with improved survival, we assessed the interaction between the V249I and the T280M genotypes. To do this, we subdivided the cases according to their genotypes into 2 groups. The first group consisted of patients that carried 3 or 4 minor alleles (V249I I/I and T280M M/M + V249 I/I and T280M T/M + V249I V/I and T280M M/M), and the second group consisted of patients with 2 or fewer minor alleles (V249I V/V and T280M T/T + V249I V/I and T280M T/M + V249I V/V and T280M M/M + V249I I/I and T280M T/T). The group of patients with 3 or 4 minor alleles had a significantly better survival (3 or 4 minor alleles median survival time 4.1 years, IQR 2.4–6.8 years; 2 or fewer minor alleles median survival time 2.7 years, IQR 1.8–4.6 years; Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for CX3CR1 assessing the interaction between V249I and T280M genotypes (P = 0.008). Three or 4 minor alleles (V249I II and T280M MM + V249 II and T280 TM + V249I VI and T280M MM; 42 cases; green line) and 2 or fewer minor alleles (V249I VV & T280M TT + V249 VI & T280TM + V249I VV & T280M MM + V249I II & T280M TT; 713 cases; blue line).

Additional analysis revealed that this difference was present only in the subgroup of patients with spinal onset (P = 0.027).

In Cox multivariable analysis, the interaction between the 2 functional variants of the CX3CR1 gene remained independently significant (the presence of 3 or 4 minor alleles has a hazard ratio of 0.69, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.46–0.93). The full model is presented in Supporting Information Table 2.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based cohort of Italian patients from the Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta ALS registry, we found that the V249I I variant of the CX3CR1 gene increased survival by 6 months. This effect was limited to spinal onset patients. The T280M M functional variant of the same gene also significantly influenced survival under an additive genetic model. We also found an interaction between the 2 variants of the CX3CR1 gene, with a significantly better survival in patients carrying 3 or 4 minor alleles. These findings were confirmed by Cox multivariable analysis. The tested variants did not differ in frequency between ALS patients and matched controls, indicating that the CX3CR1 gene is not a risk factor for ALS.

Our findings directly contradict the findings of a smaller study involving 232 Spanish ALS patients that showed that the presence of the V249I I variant was associated with a 25-month-shorter survival.13 This disparity may be due to the population-based composition of our cohort, which is more representative of the whole ALS population. The highly selected nature of the clinic-based patients included in the Spanish study is demonstrated by the patients’ young mean age at onset and the very long survival compared with the data from epidemiological studies on ALS.20 In the case of KIFAP3 gene polymorphisms, it has been clearly demonstrated in ALS that the use of a highly selected population may give erroneous conclusions about the outcome effect of gene polymorphisms.21–23

Alternatively, it is possible that the observed discrepancy between the 2 studies indicates that the association of ALS with CX3CR1 gene common polymorphism is not real. It is noteworthy that these SNPs did not show an effect on survival in ALS patients in a previous genome-wide association study (GWAS) involving over 4,000 patients, although the large number of variants that were tested in that study resulted in a more stringent P-value threshold for declaring genome-wide significance.24 Although this is the most likely explanation, we do not want to dismiss prematurely the survival effect of CX3CR1 functional polymorphisms because 6 months represents a substantial 20% change in survival in a disease associated with rapid progression and death. Our data suggest that this gene is worthy of additional study in even larger cohorts and also highlight the importance of appropriate selection of cases and controls in such studies.

Assuming that the effect of functional CX3CR1 polymorphisms is not spurious, the modifying effect of the CX3CR1 gene on ALS survival implicates microglia regulation in the pathological process underlying ALS4 and, more generally, in the neuroinflammatory component of motor neuron degeneration. The CX3CR1 protein is a key element of the neuron–microglia interactions. It is notable that the 2 variants, V249I and T280M, affect functionality and activity of the protein through different mechanisms. The V249I I variant causes a reduced function through the reduction of the number of CX3CR1 binding sites and its binding affinity on peripheral mononuclear cells,12 whereas the 280M variant reduces cell-to-cell adhesion.8,12 However, other mechanisms related to systemic immunity in addition to microglia function can also be considered.3,4

The disparity between our findings and those reported in CX3CR1−/− knockout mice inbred with the SOD1G93A transgenic ALS model, which demonstrated a worsened disease outcome and increased microglial activation,6 is only apparent. Because of the dual effect of microglia in ALS,4 it is likely that, in the CX3CR1−/− knockout mouse, the increased microglia activity worsens the disease, whereas, in the case of the V249I I variant in humans, only a reduction of function is observed, with a consequent modulating effect on microglia activity.

In the past few years, several studies of genetic modifiers of ALS phenotype or prognosis have been conducted. The rs12608932CC genotype of the UNC13A gene has been demonstrated in several populations to be related to a shorter survival than the A/C and A/A genotypes.24–27 More recently, a large international meta-analysis of GWAS found 2 loci (at 10q23, SNP rs139550538 and at 1p36, rs2412208) in which the presence of the minor alleles in the homozygous state were significantly associated with a reduction of survival of 7 and 4 months, respectively.28 Also, the presence of at least 1 minor allele of the rs3011225 SNP located on chromosome 1p34.1 was associated with earlier age of onset in a meta-analysis of 13 GWAS cohorts.29 Finally, the presence of an intermediate CAG repeat expansion in the ATXN2 gene not only is a risk factor for ALS24 but also is associated with a spinal phenotype and reduces survival by 1 year.30,31

In summary, we used a large population-based cohort of ALS patients to show that functional variants of the CX3CR1 gene potentially influence ALS survival. A limitation of our study is that it is based on a candidate-gene approach. Although this approach is less powerful than data-driven, genome-wide techniques, several attributes enhance the value of our data. First, this study was performed with an adequately powered cohort. Second, this cohort is population based, so it is representative of the more general ALS community. Third, the evaluated SNPs are known to alter significantly the function of the protein encoded by the gene. Our data suggest that functional modification of this gene influences survival in ALS patients and, by extension, implicate neuroinflammation as an important determinant of the rate of progression, perhaps opening new avenues for ALS treatment. Nevertheless, we recognize the disparate results compared with the previous study of this gene13 and recommend that even larger cohorts of appropriately collected ALS patients be studied. Large multicenter studies that are currently ongoing in Europe and the United States may help to clarify this issue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata 2010; grant RF-2010-2309849); the European Community Health Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013 under grant agreements 278611 and 259867); the Joint Programme– Neurodegenerative Disease Research (Italian Ministry of Education and University; Sophia, and Strength Projects); the Associazione Piemontese per l’Assistenza alla SLA, Torino, Italy; the Fondazione Mario e Anna Magnetto, Alpignano, Torino; and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health.

A. Calvo and C. Moglia have received research support from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata). G. Mora has received research support from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata) and Agenzia Italiana per la Ricerca sulla SLA. A. Chiò serves on the editorial advisory board of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and has received research support from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Finalizzata), Regione Piemonte (Ricerca Finalizzata), University of Turin, Fondazione Vialli e Mauro onlus, and the European Commission (Health Seventh Framework Programme) and serves on scientific advisory boards for Biogen Idec, Cytokinetics, Italfarmaco and Neuraltus.

Abbreviations

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ANG

angiogenin

- C9ORF72

chromosome 9 open reading frame 72

- CX3CR1

chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor 1

- FUS

fused in sarcoma

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

- IQR

interquartile range

- PARALS

Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta Register for ALS

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase 1

- TARDBP

TAR DNA binding protein

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflicts of Interest: A. Canosa, S. Cammarosano, A. Ilardi, D. Bertuzzo, B. J. Traynor, M. Brunetti, M. Barberis, and F. Casale report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Publication Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines

References

- 1.Al-Chalabi A, Hardiman O, Kiernan MC, Chiò A, Rix-Brooks B, van den Berg LH. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: moving towards a new classification system. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:1182–1194. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooten KG, Beers DR, Zhao W, Appel SH. Protective and toxic neuroinflammation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12:364–375. doi: 10.1007/s13311-014-0329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medina-Contreras O, Geem D, Laur O, Williams IR, Lira SA, Nusrat A, et al. CX3CR1 regulates intestinal macrophage homeostasis, bacterial translocation, and colitogenic Th17 responses in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4787–4795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hickman SE, Kingery ND, Ohsumi TK, Borowsky ML, Wang LC, Means TK, et al. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1896–1905. doi: 10.1038/nn.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardona AE, Pioro EP, Sasse ME, Kostenko V, Cardona SM, Dijkstra IM, et al. Control of microglial neurotoxicity by the fractalkine receptor. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:917–924. doi: 10.1038/nn1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ransohoff RM, Cardona AE. The myeloid cells of the central nervous system parenchyma. Nature. 2010;468:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nature09615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott DH, Fong AM, Yang Q, Sechler JM, Cupples LA, Merrell MN, et al. Chemokine receptor mutant CX3CR1-M280 has impaired adhesive function and correlates with protection from cardiovascular disease in humans. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1241–1250. doi: 10.1172/JCI16790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daoudi M, Lavergne E, Garin A, Tarantino N, Debrè P, Pincet F, et al. Enhanced adhesive capacities of the naturally occurring Ile249–Met280 variant of the chemokine receptor CX3CR1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19649–19657. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arli B, Irkec C, Menevse S, Yilmaz A, Alp E. Fractalkine gene receptor polymorphism in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J Neurosci. 2013;123:31–37. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.723079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuo J, Smith BC, Bojanowski CM, Meleth AD, Gery I, Csaky KG, et al. The involvement of sequence variation and expression of CX3CR1 in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. FASEB J. 2004;18:1297–1299. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1862fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moatti D, Faure S, Fumeron F, Amara MEW, Seknadji P, McDermott DH, et al. Polymorphism in the fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 as a genetic risk factor for coronary artery disease. Blood. 2001;97:1925–1928. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Lopez A, Gamez J, Syriani E, Morales M, Salvado M, Rodríguez MJ, et al. CX3CR1 is a modifying gene of survival and progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PloS One. 2014;9:e96528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiò A, Mora G, Calvo A, Mazzini L, Bottacchi E, Mutani R, et al. Epidemiology of ALS in Italy: a 10-year prospective population-based study. Neurology. 2009;72:725–731. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000343008.26874.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks BR, Miller RG, Swash M, Munsat TL World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Motor Neuron Diseases. El Escorial revisited: revised criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2000;1:293–299. doi: 10.1080/146608200300079536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiò A, Schymick JC, Restagno G, Scholz SW, Lombardo F, Lai SL, et al. A two-stage genome-wide association study of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1524–1532. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schymick JC, Scholz SW, Fung HC, Britton A, Arepalli S, Gibbs JR, et al. Genome-wide genotyping in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and neurologically normal controls: first stage analysis and public release of data. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:322–328. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiò A, Calvo A, Mazzini L, Cantello R, Mora G, Moglia C, et al. Extensive genetics of ALS: a population-based study in Italy. Neurology. 2012;79:1983–1989. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182735d36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauderman WJ. [Accessed March 28, 2017];QUANTO 1.2.4: a computer program for power and sample size calculations for genetic-epidemiology studies. http://biostats.usc.edu/Quanto.html.

- 20.Chiò A, Logroscino G, Hardiman O, Swingler R, Mitchell D, Beghi E, et al. Prognostic factors in ALS: a critical review. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2009;10:310–323. doi: 10.3109/17482960802566824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landers JE, Melki J, Meininger V, Glass JD, van den Berg LH, et al. Reduced expression of the kinesin-associated protein 3 (KIFAP3) gene increases survival in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9004–9009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812937106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traynor BJ, Nalls M, Lai SL, Gibbs RJ, Schymick JC, Arepalli S, et al. Kinesin-associated protein 3 (KIFAP3) has no effect on survival in a population-based cohort of ALS patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12335–12338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914079107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Doormaal PT, Ticozzi N, Gellera C, Ratti A, Taroni F, Chiò A, et al. Analysis of the KIFAP3 gene in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a multicenter survival study. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2420.e13–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fogh I, Lin K, Tiloca C, Rooney J, Gellera C, Diekstra FP, et al. A locus in the CAMTA1 gene is associated with survival in patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:812–820. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diekstra FP, van Vught PWJ, van Rheenen W, Koppers M, Pasterkamp RJ, van Es MA, et al. UNC13A is a modifier of survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:e3–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiò A, Mora G, Restagno G, Brunetti M, Ossola I, Barberis M, et al. UNC13A influences survival in Italian amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: a population-based study. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vidal-Taboada JM, Lopez-Lopez A, Salvado M, Lorenzo L, Garcia C, Mahy N, et al. UNC13A confers risk for sporadic ALS and influences survival in a Spanish cohort. J Neurol. 2015;262:2285–2292. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7843-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ALSGEN Consortium. Age of onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is modulated by a locus on 1p34.1. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:357.e7–357.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang MD, Gomes J, Cashman NR, Little J, Krewski D. Intermediate CAG repeat expansion in the ATXN2 gene is a unique genetic risk factor for ALS. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PloS One. 2014;9:e105534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiò A, Calvo A, Moglia C, Canosa A, Brunetti M, Barberis M, et al. ATXN2 polyQ intermediate repeats are a modifier of ALS survival. Neurology. 2015;84:251–258. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borghero G, Pugliatti M, Marrosu F, Marrosu MG, Murru MR, Floris G, et al. ATXN2 is a modifier of phenotype in ALS patients of Sardinian ancestry. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;36:2906.e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.