Abstract

Background:

Medical education is moving toward active learning during large group lecture sessions. This study investigated the saturation and breadth of active learning techniques implemented in first year medical school large group sessions.

Methods:

Data collection involved retrospective curriculum review and semistructured interviews with 20 faculty. The authors piloted a taxonomy of active learning techniques and mapped learning techniques to attributes of learning-centered instruction.

Results:

Faculty implemented 25 different active learning techniques over the course of 9 first year courses. Of 646 hours of large group instruction, 476 (74%) involved at least 1 active learning component.

Conclusions:

The frequency and variety of active learning components integrated throughout the year 1 curriculum reflect faculty familiarity with active learning methods and their support of an active learning culture. This project has sparked reflection on teaching practices and facilitated an evolution from teacher-centered to learning-centered instruction.

Keywords: Active learning, interactive learning, critical thinking, learning-centered curriculum

Introduction

Over the past decade, reform efforts in medical and health care education curricula have emphasized the importance of active learning (AL) and technology to improve student engagement and critical thinking skills.1–5 Key medical education conferences, such as the International Association for Medical Science Educators, have included workshops and instructional guides to improve AL techniques.6 Other visionary higher education organizations such as EDUCAUSE prescribe AL expressly designed for the millennial generation and beyond.7,8 Although much has been written about AL, there is a gap in the literature regarding medical schools tracking the saturation of these activities in undergraduate medical curricula.

What is AL? AL is an umbrella term9,10 that embraces a variety of teaching and learning techniques. These include case-based learning, experiential learning,11 peer problem solving,12 and project-based learning.13 Popular Technology-Enhanced Active Learning (TEAL) media include audience response,14 vodcasts,15 virtual patient simulation,16 and online games.17 New media include mediated immersion platforms for the current neo-millennial generation, such as virtual reality,18 and wearable technology.18

Active learning represents a shift away from exposition instruction that has a tendency to render learners bored or passive.19–21 Students take responsibility for their learning by engaging in activities or discussion in class. This method emphasizes higher-order thinking and often involves group work.4 Well-designed AL lessons have been found to be effective for maximizing learning,4,9,22 engagement,23 peer collaboration,24 and evidence-based medicine.5,21

Although AL is widely recommended for medical education, it is common wisdom that not every instructor is comfortable or expert in this approach to instruction. A 2011 survey of faculty at all US colleges of pharmacy5 suggested that faculty who spend more time teaching are more inclined to use AL techniques. There is a trend for newer institutions and younger faculty to use AL. Despite the advantages, faculty are sometimes hesitant to transform teaching practice due to beliefs, such as needing to cover all pertinent and available material.25

What is learning-centered education (LCE) at the classroom level? Learning-centered education10,13,26 is part of a wider trajectory of curricular and pedagogical reform in higher education,26 “has its roots in constructivism and context-based theories,” and places emphasis on learning communities, integration, diverse pedagogies, and learning outcomes.26 Consistent with AL, the goal of the learning-centric model is to train students to be proactive partners in the learning progression: to lean in and engage. Learning-centered education works well for medical education because through situated cognition,27 students develop professional competency.28 In reviewing LCE literature, it appears that rich, effective learning for medical students happens under certain conditions, as follows:

Real-world relevance. Medical students are adult learners, motivated by goals and tasks relevant to them, or that have real-world application.11 In presenting content, instructors emphasize the relevant, high-yield tasks and correlate concepts to clinical applications.

Competency based. Data-driven or competency-based education approaches such as milestones29 support student-directed learning. Instructors design learning following the cycle: objectives-teach-assess, accentuating authentic performances and frequent feedback.10,30 After instruction, faculty review learning performance data in a systematic manner31 to improve learning and delivery.13 Students take a proactive part in the learning cycle10,30—engaging actively, self-monitoring, responding to feedback, and adapting to new learning challenges.

Collaboration. Peer collaboration, sometimes referred to as relational, cooperative,13 or team-based learning,2 emphasizes cocreation of knowledge, problem solving in teams, respect, cultural competence, and participatory engagement.

Deliberate practice. To progress from novice to expert, medical students need ample opportunities to digest theoretical concepts and practice new skills,29,32 with instructive feedback as they progress.

Technology/multimedia. Modern medical education environments integrate current learning technologies and new media.33 This results in increased engagement, enhanced collaboration, real-world application, clinical decision making, distance training, learning analytics,1 and swift feedback.17

Aims

The aims of this study were to measure the nature and saturation of AL teaching methods in large group (LG) sessions and investigate the relationship between AL components and learning-centered attributes. Research questions were as follows:

Which AL techniques were used and to what degree?

What percent of the Medical School, Year 1 (MSI) LG curriculum has an AL component?

Was the AL taxonomy (Table 1) effective for tracking AL?

How do the AL components align to the attributes of LCE?

Table 1.

A taxonomy of active learning techniques.

| Active learning techniques | |

|---|---|

| Component/technique | Description |

| 1. Audience response | Individual students respond to application of skill questions via an audience response system (ARS) or poll34 |

| 2. Vodcast + pause activities | A video podcast with pause activities, appended exercises, or practice questions |

| 3. Vodcast + hyperlinks | A video podcast with no pause activities but includes hyperlinks to external or Web media for enrichment |

| 4. Interactive vodcast | A vodcast that requires students to physically click through questions or interactivities. (vodcasts using Flash) |

| 5. Interactive module | An electronic lesson, often audiovisual, that requires students to complete interactivities |

| 6. Case-based instruction | The use of patient cases to stimulate discussion, questioning, problem solving, and reasoning on issues pertaining to the basic sciences and clinical disciplines35 |

| 7. Demonstration | A performance or explanation of a process, illustrated by examples, realia, observable action, specimens, etc35 |

| 8. Discussion or debate | Instructors facilitate a structured or informal discussion or debate |

| 9. Game | An instructional method requiring the learner to participate in a competitive activity with preset rules36 |

| 10. Flipped classroom | The traditional lecture and homework elements of a course are reversed. Short video lectures or electronic handouts are viewed by students before class. In-class time is devoted to exercises, projects, or discussions24 |

| 11. Interview or panel | Students interview standardized patients or experts to practice interviewing and history-taking skills |

| 12. Learning station | Students rotate through learning stations, participating in performance exercises at each station |

| 13. Worksheet or problem set | Learners work in pairs or teams to solve problems or categorize information. May be “peer-to-peer” (same training level) or “near-peer” (higher-level learner teaching lower-level learner) |

| 14. CP Scheme | An interactive exercise that encourages learners to make clinical decisions following a clinical presentation scheme (flowchart)37 |

| 15. Simulation or role play | A method used to replace or amplify real patient encounters with scenarios designed to replicate real health care situations, using lifelike mannequins, physical models, or standardized patients37 |

| 16. Oral presentation | Students present on topics to their peers. Professors and peers evaluate the presentations using a specific rubric |

| 17. Team-based activity | A collaborative learning activity that fosters team discussion, thinking, or problem solving |

| 18. POPS cases | A 4-part simulated case scenario wherein each student, working in a group of 4, has the solution to his or her part and must guide the others through a mutual solution |

| 19. Problem-based learning | Working in peer groups, students identify what they already know, what they need to know, and how and where to access new information that may lead to the resolution of the problem |

| 20. Lab or studio | Students apply knowledge in lab, by engaging in a hands-on or kinesthetic activity |

| 21. Word activity | Students complete a word-based activity, such as a crossword puzzle, definitions activity, or memorization sequence |

| 22. Concept maps/drawings | Students generate concept maps, drawings, or graphics illustrating concepts |

| 23. Annotations or notes | Students submit notes or annotations using a recommended style or platform such as OneNote |

| 24. Formative quizzes | The lesson includes a set of questions bundled together into a quiz, which allows learners to self-assess |

| 25. Technology-Enhanced Active Learning (TEAL) | An interactive lesson integrating educational technology, such as electronic games, mobile apps, virtual simulations, EHR, videoconferencing, Web exercises, or bioinstruments38 |

Abbreviations: CP Scheme, Clinical Presentation Scheme; EHR, Electronic Health Record; POPS, Patient-Oriented Problem Solving.

Taxonomy developed by the ATSU-SOMA TEAL Team 2017.

Real-world relevance.

Competency based.

Collaboration.

Deliberate practice.

Technology/multimedia.

Methods

Setting and participants

The setting for this study was an American Osteopathic College of Medicine (COM) located in the Southwest United States. Participants were 20 medical school faculty responsible for teaching a series of systems-based courses to a cohort of 108 first year medical students.

Research design

This study employed a sequential, explanatory mixed methods design in the tradition of a retrospective curriculum evaluation,39 supplemented by focused interviews with 20 faculty. The curriculum reviewed in 2017 included lesson content for LG sessions taught during first year medical school (MSI) in academic year 2015-2016, but excluded lessons for 3 other concurrent curriculum strands that conventionally rely on experiential or AL: Medical Skills, Anatomy Lab, and Osteopathic Principles and Practice. The university’s Institutional Review Board exempted this study.

Data collection process

Data collection was an 8-step process, provided in detail here so other institutions may replicate this study:

Step 1. Study authors coded each of the 25 learning activities listed in the taxonomy entitled AL Techniques with an alpha code (Table 1).

Step 2. The school’s curriculum manager (CM) conducted a retrospective review of the MSI 2015-2016 LG curriculum, by accessing the MSI weekly academic calendar in Google Calendars, downloading print copies of the weekly course schedule for each of 9 consecutive systems-based courses, and finally shading the LG sections of each day in the week.

Step 3. The CM accessed the associated learning modules for each course in the Blackboard learning management system (LMS) to review content and delivery format for each hour-long lesson.

Step 4. Using the weekly course schedule calendar printouts, the CM used the Taxonomy to assign a code for any AL techniques, evidenced by the content posted in the LMS for each hour of each day of instruction recorded in the course content notes. Some techniques were multiple coded using the simultaneous coding40 method. For example, for a given 1-hour LG session, the same activity, such as an electronic, case-based game could be multiple coded: (1) game, (2) TEAL, and (3) case-based instruction. Each of those 3 separate components would be counted in the total frequency count for AL components for 1 AL session. This increased the count of AL components for the entire academic year.

Step 5. The CM conducted individual, consented, semistructured interviews with 20 faculty members involved in teaching 9 MSI courses (see Supplementary Appendix 1 for the interview protocol). This process involved reviewing the Taxonomy and then discussing each LG hour of each course taught by that instructor. In this regard, the review of past lessons functioned as a self-evaluation for each instructor.

Step 6. The CM tallied the frequency of AL components per each 1-hour LG session.

Step 7. The CM tallied the AL technique codes by course.

Step 8. After completing the interviews, the CM debriefed with the research team regarding faculty interest and level of participation in the interview sessions.

Materials and instruments

Taxonomies are helpful to educators, as they “assist with categories and distinctions, which then draw attention to ideas.”41 Furthermore, taxonomies provide definitions that help to operationalize variables in education research.41 Earlier AL matrices have been proposed by AAMC,35 Wolff et al,21 and Stewart et al,5 but the Taxonomy entitled AL Techniques (Table 1) was developed through the COM’s TEAL Committee and ratified through faculty consensus. Over the past 7 years, many of the AL techniques listed in the Taxonomy were tested with students through prior studies at this institution.17,23,24,43 It is apparent from the results of these studies that these learning experiences provided the opportunity for students to be proactive, engage, critically think, collaborate, and measure their own progress through immediate feedback.

LCE attributes

The authors identified 5 constructs (attributes) associated with LCE using the following process. Members of the authorship team reviewed the literature and achieved a consensus regarding 5 key attributes of LCE at the classroom level. The authorship team then independently mapped each AL technique to 1 of the 5 attributes. Next, researchers compared results to develop consensus codes for Table 2.

Table 2.

Attributes of learning-centered education, as applied to learning activities.

| Attribute | Description of learning activity | Color |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Real-world relevance | Demonstrates the clinical relevance of the material, including clinical decision making, public health, or social determinants | Purple |

| 2. Competency based | Allows learner to assess progress through frequent feedback or rich mentorship | Red |

| 3. Collaboration | Focuses on consensus, teamwork, peer discussion, consensus decisions, and respectful communication | Blue |

| 4. Deliberate practice | Provides opportunities to memorize, rehearse, review, study, and digest new concepts in the pursuit of critical thinking | Green |

| 5. Technology/multimedia | Integrates health information technology, informatics, bioinstrumentation, or multimedia to introduce a more 3D experience, electronic media (vodcasts, electronic games, videoconferencing, EHR, virtual simulation, electronic databases, mobile apps, etc) | Yellow |

The authors developed this categorization, 2017.

Results

Research question 1. Which AL techniques were used, and to what degree? Table 3 presents the frequency of each AL technique used. In summary, professors integrated all 25 AL components into MSI LG sessions.

Table 3.

Frequency of learning activity by year 1 course, 2015-2016.

| Component/technique | 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSF | FOH | NMSK-A | NMSK-B | CP1 | CP2 | REM1 | REM2 | GI | Total | |

| 1. Audience response | 5 | 19 | 9 | 18 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 86 |

| 2. Vodcast + pause activities | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 12 | 32 |

| 3. Vodcast + hyperlinks | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 17 |

| 4. Interactive vodcast | 7 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 19 |

| 5. Interactive module | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 6. Case-based instruction | 3 | 1 | 15 | 22 | 3 | 21 | 21 | 15 | 19 | 121 |

| 7. Demonstration | 8 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 60 |

| 8. Discussion/debate | 5 | 29 | 19 | 25 | 9 | 34 | 26 | 18 | 18 | 183 |

| 9. Game | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 25 |

| 10. Flipped classroom | 6 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 33 |

| 11. Interview or panel | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 12. Learning station | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 13. Worksheet/problem set | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 34 |

| 14. CP Schemea | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 32 |

| 15. Simulation/role play | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| 16. Oral presentation | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 17. Team-based activity | 5 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 37 |

| 18. POPSb cases | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| 19. Problem-based learning | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 20. Lab or studio | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 21. Word activity | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 17 |

| 22. Concept maps/drawings | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 |

| 23. Annotations or notes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 24. Formative quizzes | 9 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 17 | 8 | 7 | 13 | 84 |

| 25. TEALc | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 15 |

| Total | 71 | 117 | 88 | 126 | 40 | 144 | 90 | 71 | 105 | 867d |

Abbreviations: BSF, Basic Structural Foundations; CP, cardiopulmonary; FOH, Foundations of Health; GI, gastrointestinal; NMSK, neuromusculoskeletal; REM, renal-endocrine.

CP Scheme: Clinical Presentation Scheme.

POPS: Patient-Oriented Problem Solving.

TEAL: Technology-Enhanced Active Learning.

Some large group sessions were multiple coded; for example, for a given 1-hour LG session, a professor introduces an electronic, case-based game. This activity would be assigned 3 codes: (1) game, (2) TEAL, and (3) case-based instruction.

Active learning components implemented most frequently were as follows:

Discussion/debate (183);

Case-based instruction (121);

Audience response (86);

Formative quizzes (84);

Demonstration (60).

Active learning components implemented least frequently were as follows:

Annotations or notes (1);

Learning stations (2);

POPS (Patient-Oriented Problem Solving) cases (5);

Oral presentations (by students) (6);

Interactive (online) modules (6).

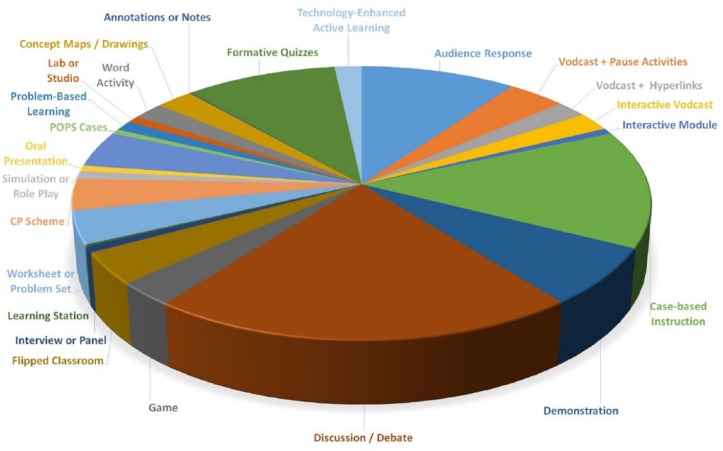

To better visualize saturation of AL components, Figure 1 presents the data from Table 2 in a pie graph format. In terms of breadth and variety of techniques used, these data indicate that professors (1) experimented with a diverse portfolio of AL techniques and (2) incorporated all of the techniques over the course of the academic year. The fact that the activities were distributed over all 9 courses indicates that there was no point in the first year in which the courses relied on purely lecture-based instruction with no AL components.

Figure 1.

Active learning techniques, MSI, AY 2015-2016.

Research question 2. What percent of the MSI LG curriculum has an AL component? Table 4 presents the percent of LG sessions that included AL components. There were 646 LG hours in the first year curriculum, with an average of 74% including an AL component.

Research question 3. Was the Taxonomy (Table 1) effective for tracking AL? At the time of the study, the Taxonomy was familiar to faculty. During the process of semistructured interviews, faculty accepted all current categories and suggested no new categories. For the category Discussion or Debate, most faculty indicated that they infused discussion rather than formal debate.

Research question 4. How do the AL components align to the attributes of LCE? Table 5 demonstrates how specific AL techniques map to the 5 attributes of LCE. Although each LCE attribute might map to additional activities, authors coded each activity to the LCE attribute with the best fit.

Table 4.

MSI courses over the 2015-2016 academic year—percent of large group sessions using active learning components.

| Code | Course title | Duration in weeks | Total large group hours | Active learning hours | % active learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BSF | Basic Structural Foundations (anatomy) | 3 | 25 | 23 | 92 |

| 2. FOH | Foundations of Health | 4 | 72 | 61.5 | 85 |

| 3. NMSK-A | Neuromusculoskeletal A | 5 | 72 | 47.5 | 66 |

| 4. NMSK-B | Neuromusculoskeletal B | 6.5 | 98 | 72.5 | 74 |

| 5. CP1 | Cardiopulmonary 1 | 3 | 42 | 27.5 | 65 |

| 6. CP2 | Cardiopulmonary 2 | 8 | 106.5 | 79 | 74 |

| 7. REM1 | Renal-Endocrine 1 | 5 | 71 | 54.5 | 77 |

| 8. REM2 | Renal-Endocrine 2 | 4 | 61.5 | 42 | 68 |

| 9. GI | Gastrointestinal | 6 | 98 | 68 | 69 |

| Total | 44.5 | 646 | 475.5 | 74 |

A relatively large percent of large group sessions (74%) included one or more active learning component. All courses demonstrate a variety of active learning components.

Table 5.

Attributes of learning-centered education mapped to active learning techniques.

| LCE code | Active learning technique |

|---|---|

| Real-world relevance | 1. Case-based instruction |

| 2. Demonstration | |

| 3. Simulation or role play | |

| Competency based | 4. Formative quizzes |

| 5. Oral presentation | |

| Collaboration | 6. Discussion or debate |

| 7. Game | |

| 8. Flipped classroom | |

| 9. Team-based activity | |

| 10. POPS cases | |

| 11. Problem-based learning | |

| 12. Worksheet or problem set | |

| Deliberate practice | 13. Interview or panel |

| 14. Learning station | |

| 15. CP Scheme | |

| 16. Lab or studio | |

| 17. Word activity | |

| 18. Concept maps/drawings | |

| 19. Annotations or notes | |

| Technology/multimedia | 20. Audience response |

| 21. Vodcast + pause activities | |

| 22. Vodcast + hyperlinks | |

| 23. Interactive vodcast | |

| 24. Interactive module | |

| 25. Technology-Enhanced Active Learning |

Abbreviations: CP Scheme, Clinical Presentation Scheme; POPS, Patient-Oriented Problem Solving.

Original Alignment, 2017.

Table 5 presents a curricular map aligning LCE attributes to AL components. Three AL components aligned to real-world relevance, 2 with competency-based, 7 with collaboration, 7 with deliberate practice, and 6 with technology/multimedia. The results of this curricular map suggest that the teaching faculty had successfully incorporated key elements of a learning-centered approach.

Discussion

The process of inventorying AL techniques used in the curriculum has been valuable. This study reflects our effort to demonstrate learning-centered culture, focused on the scholarship of teaching and learning. In the current phase, it appears that there is a promising level of saturation of AL within LG sessions (74%). The frequency and variety of AL components integrated across the 9 courses reflected faculty fluency with a range of techniques and their support of an AL culture.

The process of our inventory, data analysis, and literature review was useful in confirming preferences for sequencing AL lessons. Although AL shifts the role of instructors from givers of information to facilitators of student learning,8,42 this does not suggest a zero tolerance for didactics. Our interpretation of AL includes a phase prior to the active component (didactics) when the professor presents or reviews concepts and theories.12 Following cognitive load theory,27,28 and principles of team-based learning, facilitated, scaffolded, or mediated AL instruction is preferred, as opposed to purely constructivist, discovery learning with no facilitation.

The Taxonomy of AL Techniques was tested; it functioned well as a categorization tool, and demonstrated a degree of internal validity as categories remained stable across interviews. For faculty, the experience of tracking their own teaching methods prompted self-reflection, along with an opportunity to self-assess and reconsider whether one’s own portfolio of activities was sufficiently diverse. The inventory of AL methods helped faculty review their own portfolios to consider any underutilized techniques they might use in LG sessions. Going forward, the faculty development team intends to deepen faculty capacity to improve AL sessions through faculty learning communities and specific training on facilitation skills.

In terms of AL or LCE, there is no unified cookbook26 approach; the quintessential attributes of AL and LCE continue to be litigated in the literature, but 5 attributes of LCE—at the lesson level—surfaced through review of literature and were explanatory for our current instructional design. They represent key elements that each contributes to a rich learning experience. The results of this study served to help the research team evaluate progress toward curricular goals described in the COM’s strategic plan, as well as articulate educational values through a consensual, participatory process.

Full engagement in the scholarship of teaching regarding developing an AL culture would not have been possible without the full support of the administration and faculty. In 2013, the COM formed an ad hoc subcommittee or community of practice,43 to help guide the transition toward AL. Department chairs have been instrumental in consistently encouraging faculty to try new techniques. They supported a learning-centered culture whereby faculty and staff could participate in ratifying the Taxonomy through a modified Delphi44 method. These conditions led to a blossom period of experimentation with 25 AL techniques.

Limitations

This was a pilot study at a single institution. The results may not be generalizable to other institutions. The research design involved narrative faculty interviews, during which faculty fact-checked and self-reported regarding their lesson formats. We avoided recording faculty interviews to reduce the misperception that this study was in some fashion, an evaluative critique. Although semistructured interviews and 2 other data points allowed for triangulation of findings (lesson content loaded on the LMS and course schedule), we acknowledge the bias inherent in faculty participant self-reporting. However, faculty bias was mitigated due to evidence provided by individual faculty during interviews. For example, during interviews, most faculty checked their online lessons, including electronic files of PowerPoint and vodcast presentations, lecture capture videos, or online media such as games or interactive modules. Others consulted procedure notes, handouts, quizzes, or sample discussion questions associated with individual active lessons.

Our study aligned AL techniques to 5 attributes of LCE. In future studies, we could answer this question: Do faculty and students conceive the AL components to be learning-centered? This study did not focus on the ways in which these AL components, when implemented, specifically activated student learning, or the degree to which students took part in them. However, through several prior published studies, we had already demonstrated that AL fosters student engagement, clinical reasoning, collaboration, and self-evaluation. Indeed, our students have been full partners in testing and evaluating most of the various learning techniques listed in the Taxonomy.

Conclusions

The results of this study found that most LG hours in the first year curriculum included an AL component (74%). The components of AL implemented most frequently were discussion and debate, case-based instruction, audience response, formative quizzes, and demonstrations. Faculty used all 25 AL techniques and integrated AL components into all 9 courses; there was no point in the first year in which the courses relied on purely lecture-based instruction with no AL components. These statistics, along with the frequencies provided for each AL component, effectively measure the saturation and breadth of AL in the curriculum.

We encourage other COMs to assess the saturation and breadth of AL in their curriculum and align with the key attributes of LCE within their native institutions. At our institution, conducting this type of curricular inventory helped faculty achieve consensus, set goals, identify practice gaps, and explore ways to improve instruction. This experience has been valuable in terms of identifying specific training needs and transformations required at the instructor and institutional level to achieve a signature, well-balanced LCE approach, with the ultimate goal of preparing competent and knowledgeable physicians of the future.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_data for Tracking Active Learning in the Medical School Curriculum: A Learning-Centered Approach by Lise McCoy, Robin K Pettit, Charlyn Kellar and Christine Morgan in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the COM faculty in cooperating with this study.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: LM, RKP, and CM conceived and designed the experiments and made critical revisions and approved final version. CK analyzed the data. LM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RKP and CM contributed to the writing of the manuscript. LM, RKP, CM, and CK agree with manuscript results and conclusions and jointly developed the structure and arguments for the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures and Ethics: As a requirement of publication, authors have provided to the publisher signed confirmation of compliance with legal and ethical obligations including but not limited to the following: authorship and contributorship, conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality, and (where applicable) protection of human and animal research subjects. The authors have read and confirmed their agreement with the ICMJE authorship and conflict of interest criteria. The authors have also confirmed that this article is unique and not under consideration or published in any other publication, and that they have permission from rights holders to reproduce any copyrighted material. The external blind peer reviewers report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Stuart G, Triola M. Enhancing health professions education through technology: building a continuously learning health system. In: Proceedings of a conference recommendations; April 9-12, 2015; Arlington, VA New York, NY: The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michaelsen L, Parmelee DX, McMahon KK, Levine RE. Team-Based Learning for Health Professions Education. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krisberg K. Flipped classrooms: scrapping lectures in favor of active learning. AAMC News. May 9, 2017. https://news.aamc.org/medical-education/article/flipped-classrooms-scrapping-traditional-lectures-/. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 4. Freeman S, Eddy S, McDonough M, et al. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8410–8415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stewart D, Brown SD, Clavier CW, Wyatt J. Active-learning processes used in US pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fornari A, Poznanski A. How-to Guide for Active Learning. Huntington, WV: IAMSE; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oblinger D, Oblinger JL. Educating the Net generation, 2005. EDUCAUSE; Available electronically at https://www.educause.edu/educatingthenetgen/. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Doyle T. Learner-Centered Teaching. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chi M, Wylie R. The ICAP framework: linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educ Psychol. 2014;49:2019–2243. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tagg J. The Learning Paradigm College. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palis A, Quiros P. Adult Learning Principles and Presentation Pearls. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2014; Apr-Jun;21(2): 114–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. White P, Larson I, Styles K, et al. Adopting an active learning approach to teaching in a research-intensive higher education context transformed staff teaching attitudes and behaviours. High Educ Res Dev. 2016;35:619–633. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bilimoria D, Wheeler JV. Learning-centered education: a guide to resources and implementation. J Manage Educ. 1995;19:409–428. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gousseau M, Sommerfeld C, Gooi A. Tips for using mobile audience response systems in medical education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:647–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pettit R, Kinney M, McCoy L. A descriptive, cross-sectional study of medical student preferences for vodcast design, format and pedagogical approach. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Posel N, McGee J, Fleiszer DM. Twelve tips to support the development of clinical reasoning skills using virtual patient cases. Med Teach. 2015;37:813–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCoy L, Lewis JH, Dalton D. Gamification and multimedia for medical education: a landscape review. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2016;116:22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clarke J, Dede C, Dieterle E. Emerging technologies for collaborative, mediated, immersive learning. In: Voogt J, Knezek G, eds. International Handbook of Information Technology in Primary and Secondary Education. New York, NY: Springer; 2017:901–909. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mourad A, Jurjus A, Hussein IH. The what or the how: a review of teaching tools and methods in medical education. Med Sci Edu. 2016;26:723–728. [Google Scholar]

- 20. McLaughin K, Mandin H. A schematic approach to diagnosing and resolving lecturalgia. Med Educ. 2001;35:1135–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolff M, Wagner MJ, Poznanski S, Schiller J, Santen S. Not another boring lecture: engaging learners with active learning techniques. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmidt H, Schotanus J, Arends LR. Impact of problem-based, active learning on graduation rates for 10 generations of Dutch medical students. Med Educ. 2009;43:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCoy L, Pettit RK, Lewis JH, Allgood A, Bay C, Schwartz FN. Evaluating medical student engagement during virtual patient simulations: a sequential, mixed methods study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pettit RK, McCoy L, Kinney M. What millennial medical students say about flipped learning. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:487–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Graffam B. Active learning in medical education: strategies for beginning implementation. Med Teach. 2007;29:38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huball H, Gold N. The scholarship of curriculum practice and undergraduate program reform: integrating theory into practice. New Dir Teach Learn. 2007;2007:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brown J, Collins A, Duguid P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ Res. 1989;18:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luc J, Antonoff MB. Active learning in medical education: application to the training of surgeons. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2016;3:51–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Desy J, Reed DA, Wolanskyj A. Milestones and millennials: a perfect pairing-competency-based medical education and the learning preferences of generation Y. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;92:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grabinger S, Dunlap J. Rich environments for active learning: a definition. ALT-J. 1995;3:5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hamilton L, Halverson R, Jackson SS, Mandinach E. Using Student Achievement Data to Support Instructional Decision Making. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rajkomar A, Dhaliwal G. Improving diagnostic reasoning to improve patient safety. Perm J. 2011;15:68–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dede C. Planning for neomillenial learning styles. Educause Quart. 2005:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lymn J, Mostyn A. Audience response technology: engaging and empowering non-medical prescribing students in pharmacology learning. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. AAMC. Curriculum Inventory Standardized Instructional and Assessment Methods and Resource Types. Washington, DC: AAMC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Akl E. The effect of educational games on medical students’ learning outcomes: a systematic review: BEME Guide No 14. Med Teach. 2010;32:16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mandin H, Harasym P, Eagle C, Watanabe M. Developing a “clinical presentation” curriculum at the University of Calgary. Acad Med. 1995;70:186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. BMES. FAQ’s about BME, http://www.bmes.org/content.asp?contentid=140. Accessed October 24, 2017.

- 39. Tamir P, Amir R. Retrospective curriculum evaluation: an approach to the evaluation of long-term effects. Curriculum Inq. 1981;11:259–278. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huberman M, Miles M. Simultaneous coding. In: Saldana J, ed. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2013;62. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shulman L. Making differences: a table of learning. Change. 2010;34:36–44. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blumberg P. Developing Learner-Centered Teachers: A Practical Guide for Faculty. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43. McCoy L, Pettit RK, Lewis JH, et al. Developing technology-enhanced active learning for medical education: challenges, solutions, and future directions. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115:202–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Keller H, McCullough J, Davidson B, et al. The integrated nutrition pathway for acute care (INPAC): building consensus with a modified Delphi. Nutr J. 2015;14:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_data for Tracking Active Learning in the Medical School Curriculum: A Learning-Centered Approach by Lise McCoy, Robin K Pettit, Charlyn Kellar and Christine Morgan in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development