Abstract

Purpose

To examine effects of alkali injury of the ocular surface on meibomian gland pathology in mice.

Methods

Three µL of 1 N NaOH were applied under general anesthesia to the right eye of 10-week-old BALB/c (n = 54) mice to produce a total ocular surface alkali burn. The meibomian gland morphology was examined at days 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 by stereomicroscopy and non-contact infrared meibography. Mice were then sacrificed and eyelids processed for histology with hematoxylin-eosin and immunohistochemistry for ELOVL4, PPARγ, myeloperoxidase (a neutrophil marker) and F4/80 macrophage antigen, as well as TUNEL staining. Another set of specimens was processed for cryosectioning and Oil red O staining.

Results

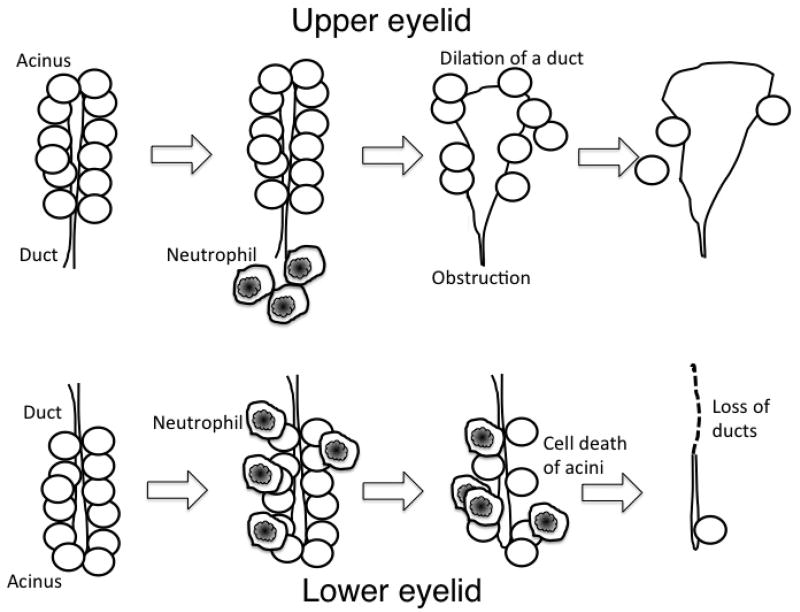

Alkali injury to the ocular surface produced cellular apoptosis, infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages, degeneration of the meibomian gland, and ductal dilation. Inflammation in and destruction of acunal stricture seemed more prominent in the lower eyelid, while duct dilation was more frequently observed in the upper eyelid during healing. Surviving acinar cells were labeled for ELOVL4 and PPARγ. Oil red O staining showed that the substance in the dilated duct contained predominantly neutral lipid.

Conclusions

Alkali injury to the ocular surface results in damage and destruction of the eyelid meibomian glands. The pattern of the tissue damage differs between glands of the upper and lower eyelids.

Keywords: Alkali burn, Histology, Meibography, Meibomian gland, mouse

1. Introduction

While alkali injury to the cornea and ocular surface is known to cause severe damage to the cornea, limbal epithelial stem cells, and conjunctiva, 1,2 little is known about the effects of alkali injury to the meibomian glands. Recently, we reported that inflammation associated with severe allergic conjunctivitis is associated with abnormal morphology of meibomian glands3. We also reported that conjunctival inflammation caused by systemic TS-1 anticancer therapy may cause obstruction of the gland orifice, leading to damage of the gland4. Because ocular surface alkali injury causes damage to both the conjunctiva and lid margin, leading to severe inflammation, it would seem likely that alkali injury may effect meibomian gland function either through direct damage to the meibomian gland, leading to scarring and plugging of the gland orifice or mediated through palpebral inflammation. To our knowledge, the effects of alkali injury to the meibomian gland has not been investigated in detail.

To determine whether meibomian glands are damaged following alkali injury, we recently conducted a preliminary simple histological examination of the meibomian gland in C57BL/6mice and showed abnormal ductal dilation of the meibomian glands5. However, melanin pigments in tissue disturbed detailed macroscopic observation, histology, and immunohistochemstry. Similar changes have been reported in human samples with ocular surface disorders 6,7, although the past history for each patient was not known or unavailable, confounding our ability to understand the relationship between alkali exposure and histological changes. In the present study, we evaluated the temporal response of the meibomian gland to alkali injury in BALB/c mice to resolve the difficulty in analysis in C57BL/6 mice as described above.

2. Materials and methods

Male BALB/c mice (n = 42) aged 10 weeks were used. The ocular surface (cornea and conjunctiva) of the right eye of each mouse was treated with 3 µl of 1N NaOH under general and topical anesthesia and allowed to heal as previously reported8,9. The treated eyes were allowed to heal without washing until specific intervals. The left eyelid of each mouse was used as a control. Mice were then sacrificed at days 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 post-exposure using CO2 asphyxia followed by cervical neck dislocation.

Upper and lower eyelids were excised en-bloc, and the meibomian gland structure was clinically documented by viewing the glands through the palpebral conjunctiva using a binocular microscope as well as under noninvasive, non-contact infrared meibography equipped with the binocular microscopy for animal study. Eyelids were then fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer. Thirty eyelids were embedded in paraffin and sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) or immunohistochemistry for ELOVL4 (elongation of very long chain fatty acids-4), a member of fatty acid elongenases 10,11(1:100 dilution, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA), PPARγ (1:100 dilution, Abcam, ab66343, Cambridge, MA, USA), myeloperoxidase (MPO, 1:100 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, neutrophil-marker) or F4/80 (1:100 dilution, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used. Antibody complex in tissue section was developed by using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine as previously reported. Paraffin sections were also processed for TUNEL staining as previously reported12. The remaining eyelids (12) were embedded in OCT compound for frozen sectioning and then stained with Oil red O (1.8×10−3g/mL, Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St Louis, MO).

3. Results

3.1. Binocular microscopy and meibography findings

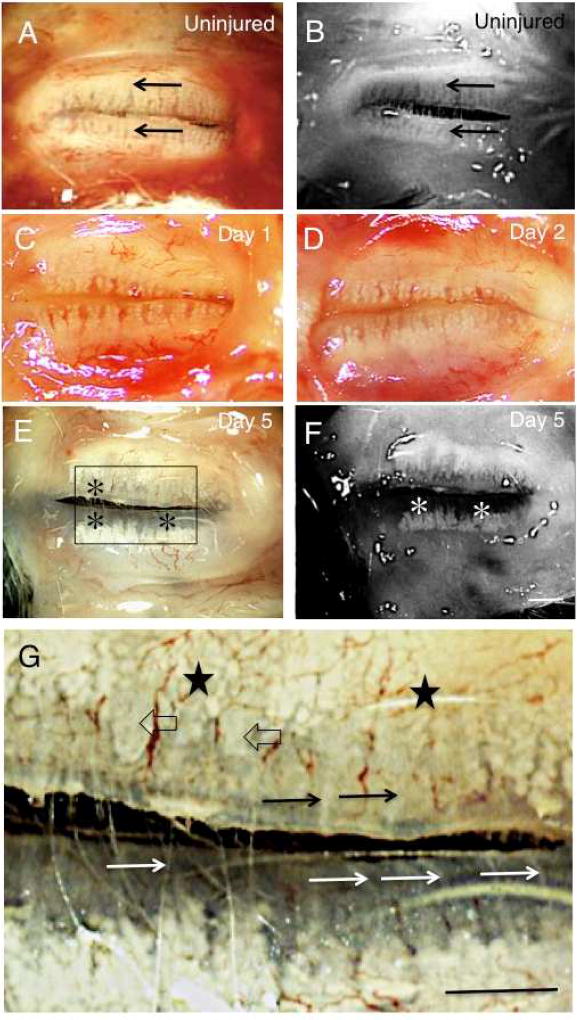

Meibomian glands in the upper and lower eyelid samples were observed through the palpebral conjunctiva using a binocular microscope before fixation (Fig. 1 A, C, D, E, G, I). Meibomian glands were arranged perpendicularly to the eyelid margins, with a large number of small acini arranged along the duct (Fig. 1 A). At days 1 (Fig. 1 C) and 2 (Fig. 1 D), the arrangement of acini in both upper and lower eyelids seemed unaffected. At day 5 post-alkali treatment (Fig. 1 E and G), the number of acini in each gland seemed to decrease, particularly near the eyelid margin, close to the orifice of the gland in both eyelids. Some of the ducts of the gland also appeared dilated, but others not, in the upper eyelid, while no dilation was detected in the lower eyelid. At day 10 (Fig. 1 H), the glands showed marked dilation of the ducts with loss of acini at the lid margin, with less severe duct dilation in the lower eyelid. At day 20 after alkali exposure (Fig. 1 J and L), meibomian glands showed continued loss of acini in both the upper and lower eyelids, with complete loss of glands in the majority of the area in the lower eyelids. Ducts in the upper eyelid were markedly dilated.

Fig. 1. Binocular microscopy and meibography findings in mouse meibomian glands following alkali injury.

A and B. In an uninjured mouse, in both the upper and lower eyelids meibomian glands contain large numbers of small acini arranged perpendicularly to the eyelid margins (arrows). C and D. At days 1 and 2, no significant abnormalities in the meibomian glands of the upper and lower eyelids are shown by binocular microscropy. E and F. At day 5 post-alkali treatment, deletion of acini is seen in the area close to the meibomian gland orifice in the lower eyelid (asterisks). Moderate dilation is seen in the duct of the glands in the upper eyelid. G. Higher magnification picture of the boxed area of day 5 specimen in frame E. Acini are not seen adjacent to the lid margin, but are clearly seen in the area relatively far from the margin (stars) in the upper meibomian glands. Naked ducts were also seen. Some ducts appear dilated (open arrows), while other are not (arrows). The loss of the acini was more marked with remaining ducts (white arrows) in the lower glands. H and I. At day 10, many ducts in the upper eyelid show marked dilation with reduction in the number of acini (arrowheads). Dilation was less severe in the lower eyelid, but the deletion of acini appears more marked in the lower eyelid (asterisks). J and K. Findings at day 20 after alkali injury are similar to those at day 10: duct dilation (arrowheads) and reduction of the number of the acini were more marked in the upper eyelid. Most of the lower eyelid showed loss of both ducts and acini (asterisks). L. Higher magnification picture of day 20 specimen in frame J. Acini were severely lost, and remaining ducts were markedly dilated (black arrows) in the upper meibomian glands. Acini and ducts are not seen in the lower eyelid. A, C, D, E, G, H, J, L: binocular microscopy; B, F, I, K: Meibography. Bar, 1 mm.

Meibographic observation in an uninjured tissue also clearly showed meibomian gland (Fig. 1 B). Such observation in the samples of day 5, 10 and 20 (Fig. 1 F, I, K) showed clearly the deletion of the acini, while the dilation of the ducts were more easily detected under binocular microscopy. These findings suggest the dilation of ducts of the meibomian glands predominate in the upper eyelid, while deletion of acini is more marked in the lower eyelid. To confirm the notion we then investigate the morphology of meibomian glands by using histology and immunohistochemistry.

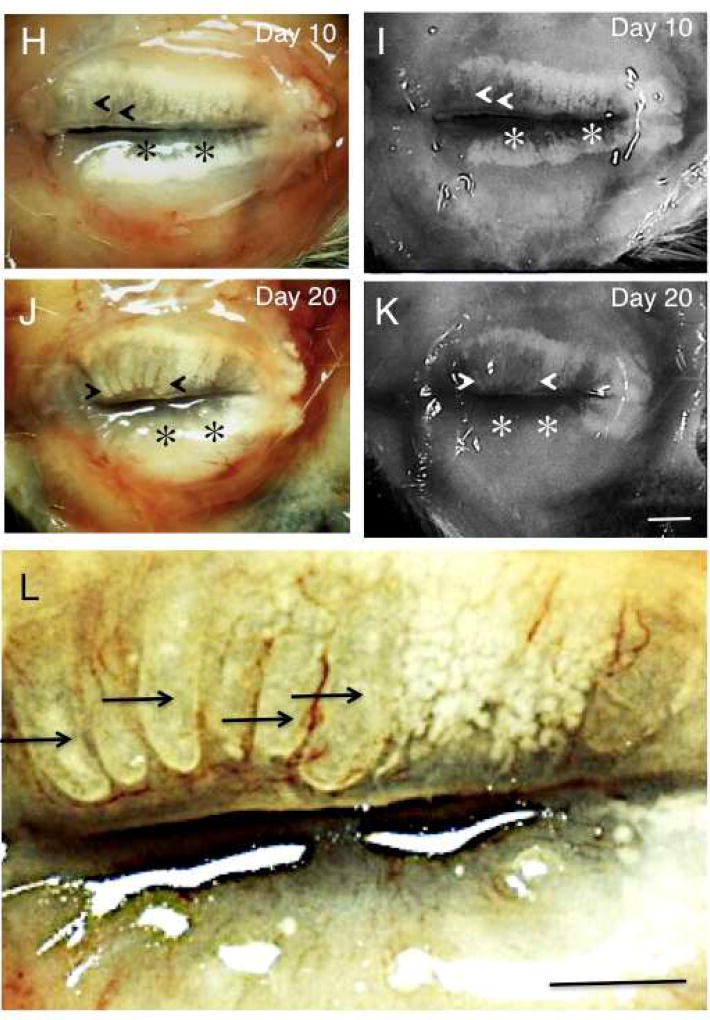

3.2. Histology findings

Well-developed meibomian glands were observed in the tarsal tissue beneath the orbicularis oculi muscle in both upper (Fig. 2 A) and lower (Fig. 2 B) eyelids. At days 1 (Fig. 2 C, D) and 2 (Fig. 2 E, F), tissue edema with cell infiltration was observed in the subconjunctival area and some of the acini of the meibomian glands. Although observation under binocular microscope did not show obvious alteration of the morphology of the meibomian glands as described above, HE histology of the day 1 and day 2 samples showed somewhat dilated ducts in the glands of the upper eyelids. On the other hand, such dilation of the ducts was not observed at these points. At day 2, meibomian glands that lacked cell nuclei were observed. The margin of the acinar structure seemed unclear in the lower eyelid as compared with that in the upper eyelid at days 1 and 2. At day 5 post-ocular surface alkali burn (Fig. 2 G), some of the gland ducts were dilated, but others were not, in the upper eyelid. Dilated ducts appeared to compress the associated acini within the gland.

Fig. 2. Histology of meibomian glands by hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Well-developed meibomian glands (asterisks) are present in the tarsal tissue beneath the orbicularis oculi muscle in both upper (A) and lower (B) eyelids. At days 1 (C and D) and 2 (E and F), tissue edema with cell infiltration is seen in the subconjunctival area (stars) and some of the acini of the meibomian glands (asterisks). At day 2, meibomian glands that lacked cell nuclei were observed (circles). At day 5, post-alkali injury, ductal dilation (arrows) is seen in some glands of the upper (G) eyelid. Dilated ducts appear to compress acini (asterisk). In the lower eyelid (H), ductal dilation is not detected. At day 10, day 5 findings have increased: duct dilation (arrows) and compressed acini (asterisks) are seen in the upper eyelid (I); duct dilation (arrows) is less severe in the lower eyelid (J). Regions with acinar dropout were occupied with cellular components in the lower lid (J). At day 20, most of the gland area shows greatly enlarged dilated ducts (arrows) in the upper eyelid (K, arrows) with few acinar structures. In the lower eyelid, the areas of meibomian glands appear to be replaced by cellular infiltrates with a few dilated ducts (arrow) (L). Bar, 200 µm.

In the lower eyelid (Fig. 2 H) duct dilation was not detected. Some of the acini exhibited a vacuole-like structure (Fig. 2 E – H). At day 10, the findings obtained at day 5 seemed more exaggerated with increased duct dilation and compression of acini observed in the upper eyelid (Fig. 2 I). Duct dilation was more frequently observed in the upper eyelid, while it was less evident in the lower lid (J).

At day 20 post-injury, upper eyelid meibomian glands were replaced with enlarged, dilated ducts, with scant acinar tissue (Fig. 2 K). In the lower eyelid, the areas of meibomian glands appeared to be replaced by cellular infiltrates with a few dilated ducts (Fig. 2 L), although an occasional enlarged duct could be detected. Histology clearly showed that the ducts of the glands are markedly dilated mainly in the upper eyelid and deletion of acini and ducts predominate in the lower eyelid during healing interval post-ocular surface alkali burn.

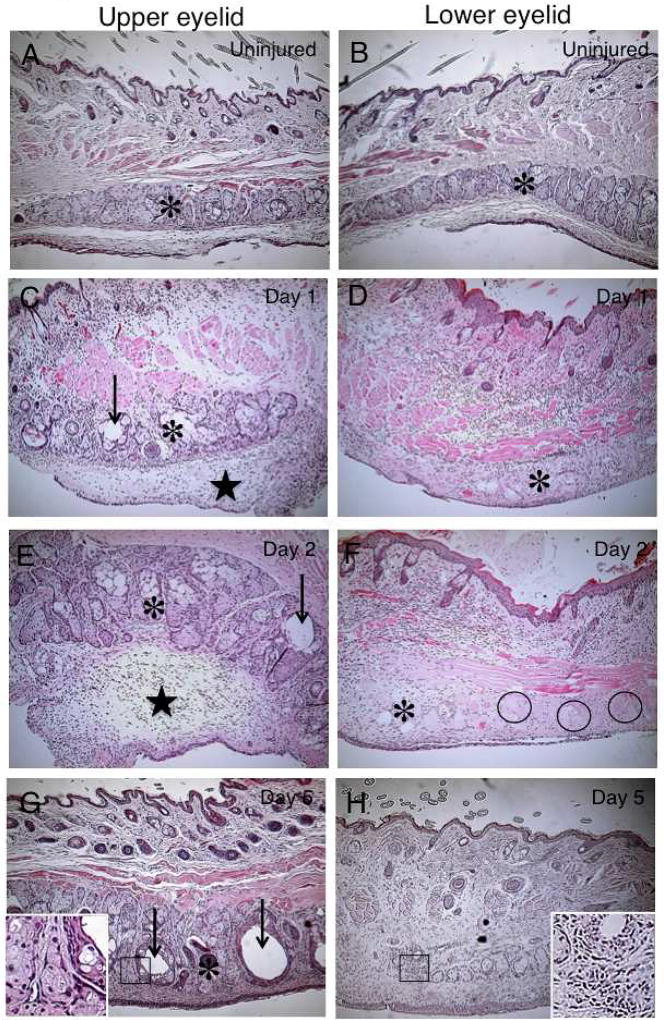

3.3 Analysis of inflammation by neutrophils and macrophages as well as cell death as detected by TUNEL staining

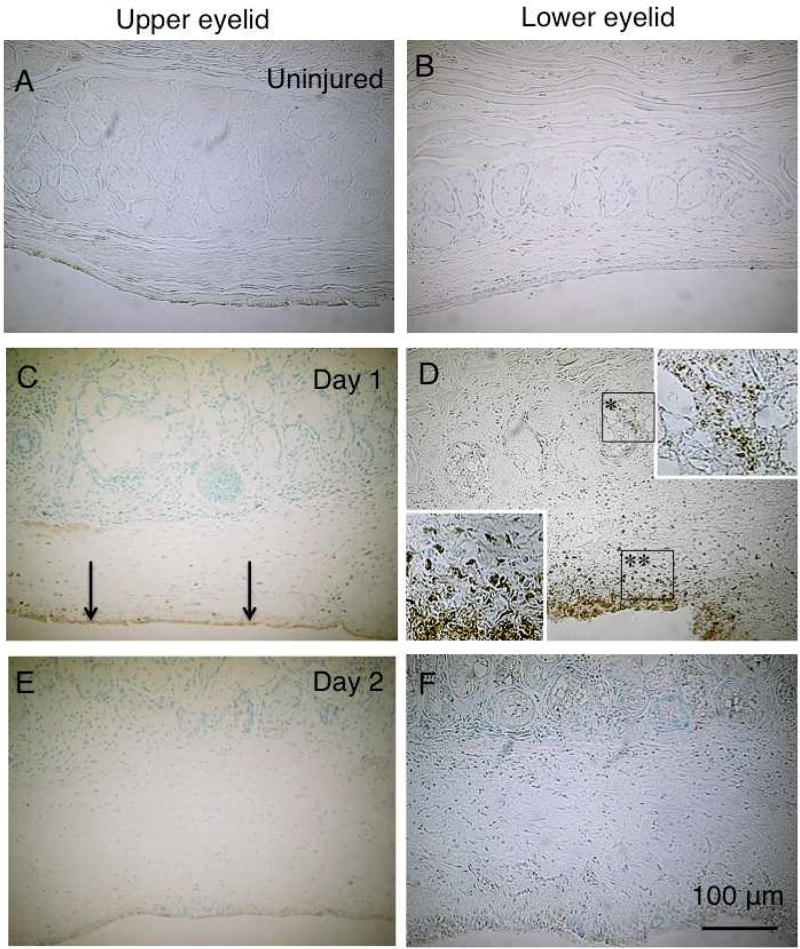

To examine the pathobiology of the injured meibomian gland, we conducted immunohistochemistry for neutrophils, macrophages and TUNEL detection of apoptotic cells. In an uninjured meibomian gland of the upper and lower eyelids neutrophils (MPO-labeled) were not detected (Fig. 3 A and B). At day 1 post-alkali burn,MPO-labeled cells were mainly detected in palpebral conjunctiva and less in subconjunctival connective tissue of the upper eyelid. On the other hand, marked infiltration of neutrophils occurred in the conjunctiva of the lower eyelid. Neutrophils were also observed in the acini of the meibomian glands of the lower eyelid. At day 2, however, infiltration of neutrophils in tissue almost disappeared in both upper (Fig. 3 E) and lower (Fig. 3 F) eyelids.

Fig. 3. Immunolocalization of neutrophils by using myeloperoxidase immunohistochemistry.

In an uninjured meibomian gland of the upper and lower eyelids, neutrophils (MPO-labeled) are not seen (A and B). At day 1 post-alkali burn, MPO-labeled cells are seen mainly in palpebral conjunctiva (arrows) and less in subconjunctival connective tissue of the upper eyelid (C), while marked infiltration of neutrophils is seen in the conjunctiva of the lower eyelid (double asterisks [D)). Neutrophils are present in the acini of the meibomian glands of the lower eyelid (area with an asterisk). Upper or lower insert indicates the area of the boxed with one or two asterisk(s), respectively). At day 2, neutrophil infiltration has almost disappeared in both upper (E) and lower (F) eyelids. Bar, 100 µm.

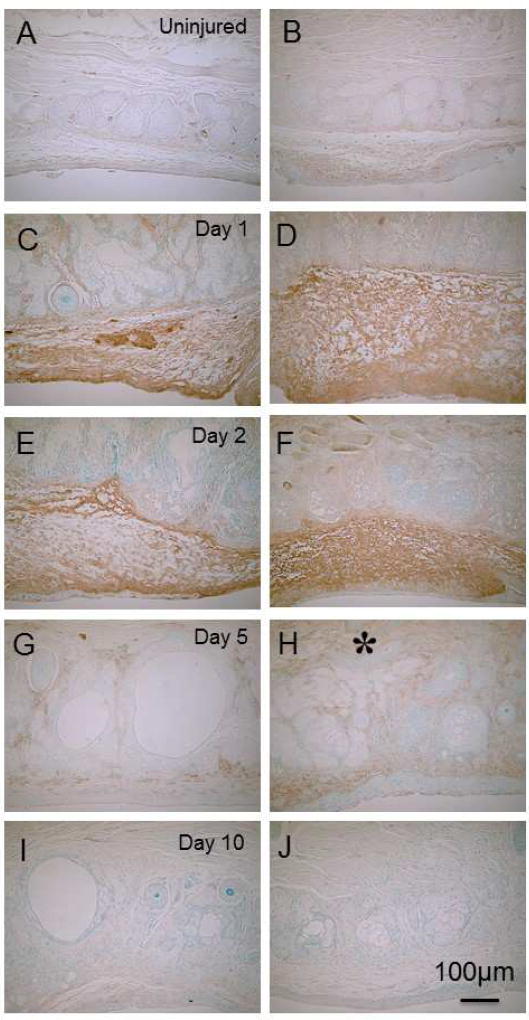

Macrophages in tissue were detected by using immunohistochemistry for F4/80 antigen. A few F4/80-labeled cells (presumed resident macrophages) were detected in tissue among acini in both upper and lower eyelids (Fig. 4 A and B). At day 1, F4/80-immunoreactive cells accumulated in the subconjunctival tissue of upper (Fig. 4 C) and lower (Fig. 4 D) eyelids. The area occupied by macrophages seemed larger in the lower eyelid tissue as compared with that in the upper eyelid. At day 2, dense macrophage accumulation was observed in the subconjunctival connective tissue of the lower eyelid (Fig. 4 F), while F4/80 immunoreactivity seemed sparse in the tissue of the upper eyelid (Fig. 4 E). At day 5, F4/80 immunoreactivity was mush regressed in both upper (Fig. 4 G) and lower (H) eyelids. Macrophage distribution seemed more prominent in the lower (Fig. 4 H) eyelid tissue as compared with upper eyelid tissue (Fig. 4 G). At days 10 and 20 (not shown), almost no macrophages were present in both eyelids (Fig. 4 I and J).

Fig. 4. Detection of macrophages by using 4/80 immunohistochemistry.

A few F4/80-labeled cells are seen in tissue among acini in both upper (A) and lower (B) eyelids. At day 1(C) and day 2 (E), F4/80-immunoreactive cells accumulated in the subconjunctival tissue of upper (D) and lower ((F) eyelids. At day 5, F4/80-immunoreactive cell distribution appear more prominent in the lower (asterisk, H) eyelid tissue than in the upper eyelid tissue (G). At day 10, almost no macrophages are seen in either eyelid (I, upper; J, lower).

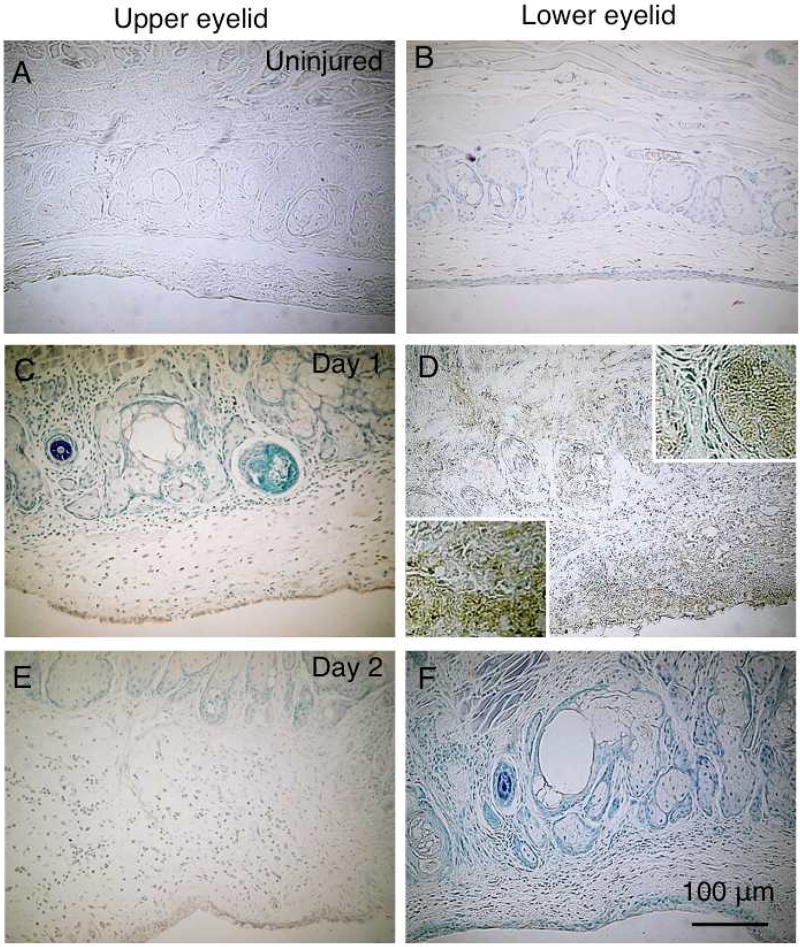

TUNEL-labeled cells were not detected in both upper and lower eyelids of an uninjured mouse (Fig. 5 A and B). At day 1 post-alkali burn, TUNEL-labeled cells were abundantly observed in the subconjunctival tissue where neutrophils were detected in the lower eyelid (Fig. 5 D). Such apoptotic cells were also seen in some of the acini, while in the upper eyelid a few TUNE-labeled cells were seen in the palpebral conjunctiva (Fig. 5 C). Few apoptotic cells were observed in both upper and lower eyelids at day 2 post-injury (Fig. 5 E and F).

Fig. 5. Detection of apoptotic cells with TUNEL staining.

TUNEL-labeled cells are not seen in upper (A) or lower (B) eyelid of an uninjured mouse. At day 1 post-alkali burn, TUNEL-labeled cells are abundantly present in the subconjunctival tissue, where neutrophils are detected in the lower eyelid (D). Such apoptotic cells are also seen in some of the acini (D), while in the upper eyelid a few TUNEL-labeled cells are seen in the palpebral conjunctiva (C). Few apoptotic cells are seen in the upper (E) and lower (F) eyelids at day 2 post-injury. Upper and lower inserts in Frame D indicate the population of TUNEL-labeled cells in the gland or subconjunctival tissue. Bar, 100 µm.

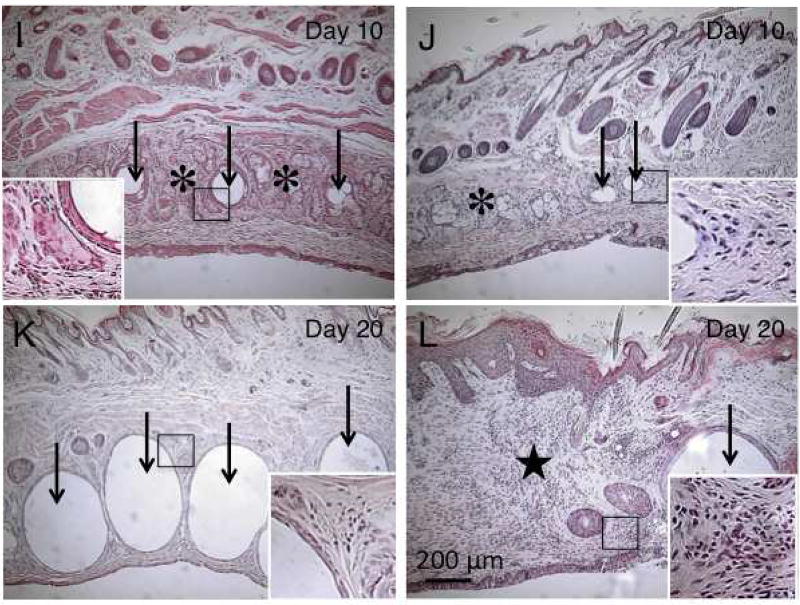

3.4. Immunohistochemistry for ELOVL4 or PPARγ

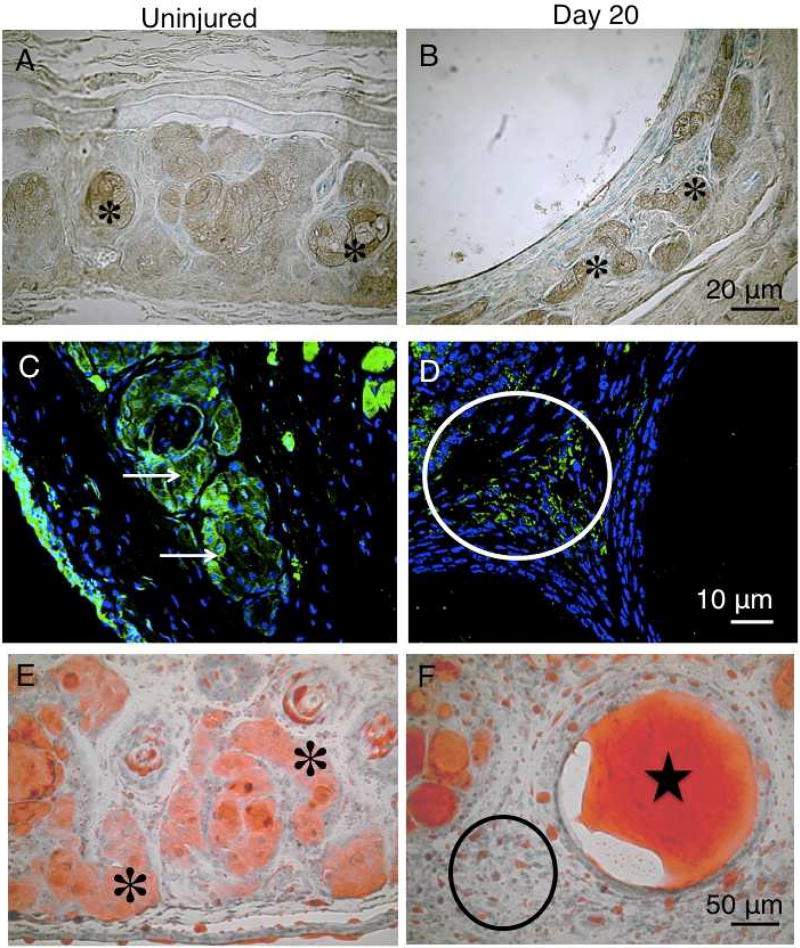

ELOVL4 is a marker of glands capable of synthesis of very long chain fatty acid synthesis, including meibomian glands and sebaceous glands. In the acinar cells of the uninjured eyelid, meibomian glands were labeled for ELOVL4 (Fig. 6 A). In an eyelid 20 days post-ocular surface alkali burn, the flattened epithelial cells on the inner surface of the dilated ducts did not stain for ELOVL4. On the other hand, acini dislocated by the dilated ducts expressed ELOVL4 (Fig. 6 B).

Fig. 6. Immunohistochemistry for ELOVL4 or PPARγ.

The acinar cells of the meibomian glands of the uninjured eyelid were labeled for ELOVL4 (A, asterisks). 20 days post-alkali burn, the flattened epithelial cells lining the inner surface of the dilated ducts did not stain for ELOVL4. Acini dislocated by the dilated ducts expressed ELOVL4 (B, asterisks). PPARγ is present in acinar cells and conjunctival epithelium of an uninjured tissue (upper eyelid [(C, arrows]). At day 20, immunostaining for PPARγ is seen in the cells distributed among the dilated ducts (D, circle). Ductal epithelium did not stain for PPARγ. Acinar cells of the normal upper eyelid exhibit oil red O-positive staining in both the cell body and duct (E, asterisk). Oil red O strongly stained material is seen in the dilated ducts 20 days post-alkali exposure (F, star), indicating the presence of meibum. Labeled droplets are seen among the dilated ducts that contain oil red O-labeled material of presumably meibum (F, circle). The oil red O-labeled droplets no longer exhibit acinar cell-like morphology (F, circle). Bar, 50 µm.

To further examine the differentiation activity of acinar cells, we then immunostained for PPARγ. PPARγ was detected in acinar cells and conjunctival epithelium in an uninjured tissue (upper eyelid [Fig. 6 C]). At day 20, immunostaining for PPARγ was observed in the cells distributed among the dilated ducts (Fig. 6 D). Ductal epithelium did not stain for PPARγ. Expression of ELOVL4 and PPARγ in the acinar cells of the meibomian glands suggest the maintenance of the acinar characteristics of the cells, while the cells lining the inner surface of the dilated ducts do not exhibit a nature of acinar cells.

To determine if the material within the dilated ducts contained meibum, we stained cryosections with oil red O. Acinar cells of the normal upper eyelid exhibited oil red O-positive staining in both the cell body and duct (Fig. 6 E). By comparison, 20 days post-alkali exposure, oil red O strongly stained material in the dilated ducts (Fig. 6 F) indicating the presence of meibum. Labeled droplets were populated among the dilated ducts that contains oil red O-labeled material of presumably meibum (Fig. 6 F). The oil red O-labeled droplets no longer exhibited acinar cell-like morphology (Fig. 6 F).

4. Discussion

The present study shows that alkali injury to the ocular surface damages not only the eye tissues, i.e., cornea and conjunctiva, but also meibomian glands. Observations using binocular microscopy and meibography showed a reduction of the number of gland acini in both upper and lower eyelids. However, it should be noted that the type of damage to the gland differed between the upper and lower eyelids. Gross morphology under binocular microscopy and meibography indicated abnormal appearance of acini or ducts at day 5 post-injury. At days 10 and 20, the reduction of the number of acini and dilation of the duct were prominent in the meibomian glands of the upper eyelid, while deletion/degeneration of the acinar cells and ducts were predominant in the lower eyelid, with dilated ducts less frequently observed. Although binocular microscopy shows the real morphology of the tissue, meibography using infrared light highlighted the morphology of the meibomian gland and showed the deletion of acini in both the upper and lower eyelid. On the other hand, dilated ducts with retention of meibum were better observed under binocular microscopy and were faintly imaged with meibography. The reason for this discrepancy in detection of the dilated duct was unknown, although the dilated duct was filled with oil red O-positive meibum. Meibum in the cytoplasm of the acinar cell and that in the duct might produce different light scattering patterns, presumably due to the size of the droplets.

The cells lining the dilated duct exhibited an elongated morphology. We have previously reported that in kidney, ureteral obstruction induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and fibrogenic reaction in the epithelial cells of proximal tubules. The phenotype is reversed by gene ablation of Smad3, the major signal transmitter for transforming growth factor β, in mice13. We hypothesized this might be the case in meibomian glands in the current study and examined vimentin expression in ductal epithelium of alkali-burned Smad3-null mouse, because dilation of ductal tissue with retention of contents could induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition. However, vimentin was not upregulated by the epithelial cells lining the inner surface of the dilated ducts in a wild-type mouse, and the phenotypic change in the dilated duct was not rescued by the loss of Smad3 (data not shown). This finding suggests that the cells lining the inner surface of the dilated duct maintained an epithelial phenotype.

ELOVL4 is a member of a family of enzymes that are involved in the synthesis of very long chain fatty acid. In eyelids, in addition to sebaceous gland, the acinar cells of meibomian gland express ELOVL4. PPARγ is reportedly involved in the morphogenesis of sebaceous and meibomian glands. Expression level of ELOVL4 and PPARγ in the acinar cells of the meibomian glands suggest the maintenance of the acinar characteristics of the cells. The acinar structure among dilated ducts was labeled for ELOVL4, indicating the cells maintain the activity of synthesizing very long chain fatty acid. PPARγ is reportedly involved in the development of lipid-secreting glands, i.e., sebaceous gland and meibomian gland14, 15. In the present study, PPARγ was detected in the cytoplasm and nuclei of the acinar cells in an uninjured tissue. It was reported that intracellular localization of PPARγ depends on age in mice; in a younger mouse, PPARγ is detected in the cytoplasm and nuclei of the acinar cells of the gland, while in aged mice it mainly locates to the nuclei. In a specimen at day 20 post-alkali burn, PPARγ was faintly detected in the acinar cells around the dilated duct, suggesting the presence of differentiation activity toward lipid-secreting cells. The cells lining the inner surface of the dilated ducts were negative for both ELOVL4 and PPARγ. This finding indicates that the epithelium does not have the characteristics of acinar cells. The cells scattered among the dilated ducts were labeled with oil red O staining, indicating they contains lipid, presumably meibum.

The exact reason why duct dilation was more marked in the upper eyelid and that acinar degeneration was more prominent in the lower eyelid during healing following alkali injury has yet to be discovered. Explanations include the possibility that the orifice of the meibomian glands might be damaged at the time of alkali exposure, leading to obstruction of the orifice, retention of meibum, and dilation of the ducts in the upper eyelid. The alkali around the upper eyelid might be easily washed out with tears. By contrast, alkali may accumulate in the lower fornix, potentially infiltrating to the meibomian glands through the palpebral conjunctiva in the inferior eyelid, resulting in greater damage to the lid margin and anterior meibomian gland. This might lead to greater acinar degeneration. To explore this notion, we performed immunohistochemistry for MPO, a neutrophil marker, and TUNEL staining for detection of apoptotic cell death. The results showed that more severe neutrophil infiltration occurs in the conjunctiva/subconjunctiva and acini in the lower eyelid than in the upper eyelid. Apoptotic cells were also more frequently seen in the lower eyelid than in the upper eyelid. These findings support the notion that alkali injury induces more severe damage to the glands and acini of the lower eyelid.

5. Conclusion

Alkali injury to the ocular surface also damages meibomian glands. In the clinical setting, meibomian glands should be carefully examined in patients with ocular surface disease from chemical injuries.

Fig. 7. Schematic of the pathology of meibomian gland following ocular surface alkali burn.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of Wakayama Medical Award for Young Researchers (to SM), Grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (C15K10876 to MK, C24791869 to TS, C25462759 to OY, C15K10878 to YO, C25462729 to SS), and NEI Eye Research Grant EY021510 (Jester).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no commercial or proprietary interest in any concept or product discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Saika S, Kobata S, Hashizume N, Okada Y, Yamanaka O. Epithelial basement membrane in alkali-burned corneas in rats: Immunohistochemical study. Cornea. 1993;12:383–390. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199309000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saika S, Uenoyama K, Hiroi K, Tanioka H, Takase K, Hikita M. Ascorbic acid phosphate ester and wound healing in rabbit corneal alkali burns: epithelial basement membrane and stroma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1993;231:221–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00918845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arita R, Itoh K, Maeda S, Maeda K, Furuta A, Tomidokoro A, et al. Meibomian gland duct distortion in patients with perennial allergic conjunctivitis. Cornea. 2010;29:858–860. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181ca3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizoguchi S, Okada Y, Kokado M, Saika S. Abnormalities in the meibomian glands in patients with oral administration of anticancer combination drug-capsule TS-1®: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:796. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1781-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mizoguchi S. Pathobiology of Meibomian gland disorders. Ganka. 2015;142:1425–1430. In Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alsuhaibani AH, Carter KD, Abràmoff MD, Nerad JA. Utility of meibography in the evaluation of meibomian glands morphology in normal and diseased eyelids. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2011;25:61–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obata H, Horiuchi H, Miyata K, Tsuru T, Machinami R. Histopathological study of the Meibomian glands in 72 autopsy cases. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1994;98:765–771. In Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saika S, Miyamoto T, Yamanaka O, Kato T, Ohnishi Y, Flanders KC, et al. Therapeutic effect of topical administration of SN50, an inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB, in treatment of corneal alkali burns in mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1393–1403. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62357-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saika S, Ikeda K, Yamanaka O, et al. Loss of tumor necrosis factor α potentiates transforming growth factor b-mediated pathogenic tissue response during wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1848–1860. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMahon A, Lu H, Butovich IA. A role for ELOVL4 in the mouse meibomian gland and sebocyte cell biology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:2832–2840. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agbaga MP. Different Mutations in ELOVL4 Affect Very Long Chain Fatty Acid Biosynthesis to Cause Variable Neurological Disorders in Humans. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;854:129–135. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-17121-0_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saika S, Saika S, Liu CY, Flanders KC, Okada Y, Miyamoto T, et al. TGFβ2 in corneal morphogenesis during mouse embryonic development. Dev Biol. 2001;240:419–432. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato M, Muragaki Y, Saika S, Roberts AB, Ooshima A. Targeted disruption of TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling protects against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1486–1494. doi: 10.1172/JCI19270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nien CJ, Massei S, Lin G, Liu H, Paugh JR, Liu CY, et al. The development of meibomian glands in mice. Mol Vis. 2010;16:1132–1140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS, et al. PPARγ is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999;4:611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]