Breakthroughs in the ability to probe and better understand biologic systems during the past 30 years1–3 have enabled the medical community to develop new therapeutic agents and change the course of many life-shortening diseases.4,5 Despite this success, bridging the gap between promising laboratory observations and the development of effective therapies remains risky and expensive, with fewer than 1 in 10,000 early translational programs successfully achieving Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, at a cost of nearly $1 billion.6 Most therapeutic development fails in the preclinical phase, which is sometimes described as the “valley of death.”7

For this reason and because therapies for some conditions will have a limited eventual market value, the pharmaceutical industry has been hesitant to initiate early-stage programs to treat so-called orphan diseases. In recognition of a critical need, federal agencies have developed programs to catalyze innovation and reduce barriers to early development of new therapies.8 In the past two decades, disease-focused foundations also have developed a new approach to bridging this preclinical gap. In a process known as venture philanthropy, such foundations have formed partnerships with industry and federal agencies to share the financial risk of therapeutic development, shorten the early translational pipeline, and advance research with “a focus on human, not financial, return.”9 In addition, foundations and their academic partners have accelerated early development by providing access to patient populations for clinical trials and assistance from disease-specific experts in study design, which has helped in bridging the gap in therapeutic development.

In this review, we will focus on three diseases— cystic fibrosis, multiple myeloma, and type 1 diabetes mellitus — to illustrate how collaborations among academic institutions, foundations, and industry partners have evolved to address the therapeutic challenges of these conditions.

Cystic Fibrosis

In 1989, the discovery of the gene that causes cystic fibrosis and the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein10,11 greatly increased interest within the scientific community in this life-shortening genetic disease, which affects approximately 70,000 patients worldwide. With support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), researchers rapidly expanded knowledge about the biogenesis, maturation, and function of CFTR, a regulated epithelial anion channel12; such knowledge provided the necessary scientific framework for the development of therapeutic targets. In addition, an international consortium13 identified more than 1700 mutations and defined genotype–phenotype correlations with standard case definitions,14 which enabled a precision-medicine approach to therapeutic development. In the 1990s, attempts were made to treat cystic fibrosis by gene-replacement therapy delivered to airway epithelia. Although early in vitro15 and in vivo studies16 provided proof of concept, many barriers, including a robust host immune response, were encountered.17 These barriers ended such initial clinical development programs.

In the decade after the discovery of the cystic fibrosis gene, scientific knowledge expanded but did not result in a therapy that corrected CFTR function. In 1999, the CFF launched the Therapeutic Development Program (TDP) to attract both academic and industry partners and to begin high-throughput screening for CFTR modulators.18,19 The CFF embraced the concept of venture philanthropy9,20 to increase the interest of industry in an orphan disease. However, the success of the TDP was based on much more than financial support.21 The program created a cultural shift that allowed the CFF, academic clinicians and scientists, federal agencies (the NIH and FDA), and industry to create a strong partnership with common goals and timelines.

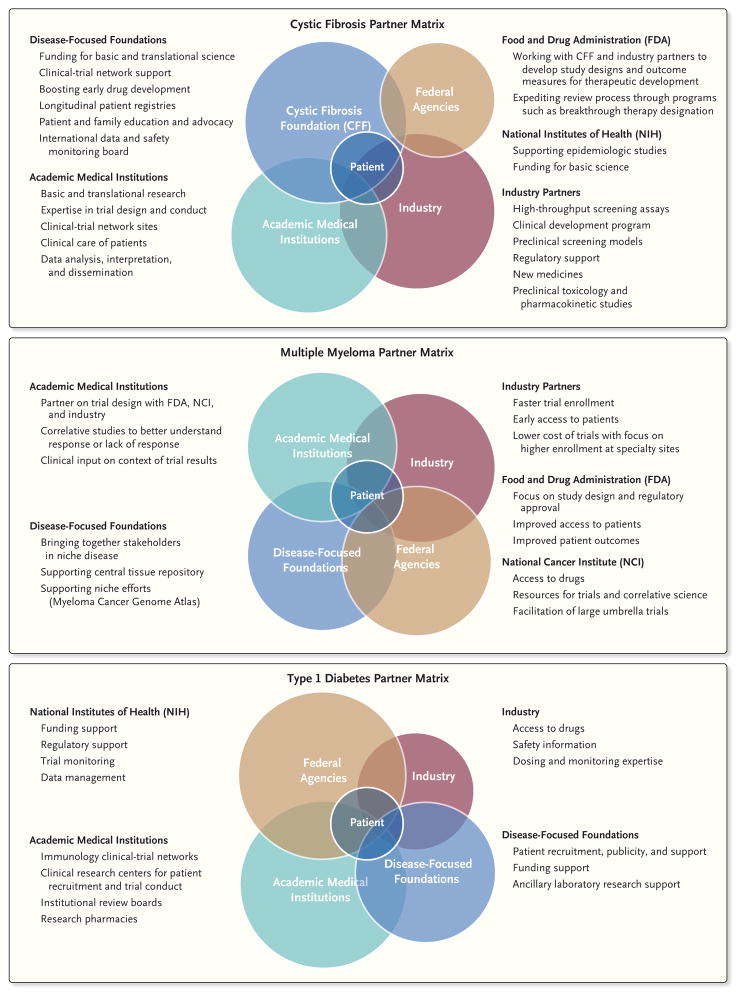

As detailed in Figure 1, each of the partners has a unique role. For example, academic centers provide expertise in the design and conduct of clinical trials, and industry brings expertise in medicinal chemistry, preclinical pharmacologic models, toxicology, and regulatory science. The CFF supports more than 120 accredited care centers in the United States and a patient registry that longitudinally tracks demographic, clinical, and genotype data on more than 20,000 patients. In addition, in 1999 the TDP launched the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutics Development Network (CF-TDN) that focuses on assisting industry partners through the therapeutic development process.22 Several strengths of the TDN and its partner, the European Cystic Fibrosis Society Clinical Trial Network, have been the establishment of uniform outcome measures and standard care practices, a common international protocol-review process, and continuous assessment of study-site metrics in order to improve the safety and efficiency of study conduct (Table 1).

Figure 1. Examples of Three Collaborative Matrixes.

Shown are three matrixes that outline the key roles of each partner in the therapeutic development process, with the common goal of benefiting patients with cystic fibrosis, multiple myeloma, or type 1 diabetes. These roles are not mutually exclusive but are often shared across the partners. Each circle represents one of the partners linked to therapeutic development. Federal agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health, have provided funds for scientific discovery. Investigators at medical academic institutions have conducted much of the fundamental scientific work and are experts in the design and conduct of clinical trials. These institutions are also the sites of clinical-trial networks, including the Therapeutics Development Network, with 82 sites in the United States, and the European Cystic Fibrosis Society Clinical Trial Network, with 43 sites in 15 countries. The pharmaceutical industry has conducted much of the preclinical work, with high-throughput screening, medicinal chemistry, toxicology, pharmacokinetics, and development of clinical trials. Foundations, such as the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, have provided the essential infrastructure to make such partnerships possible, including the support of drug discovery and development programs, the development of longitudinal patient registries, and the administrative organization for bringing together experts in the field.

Table 1.

Approaches to Partnerships among Researchers, Patient Groups, and Industry in Three Diseases.

| Disease and Barriers Encountered | Solutions to Overcome Barriers |

|---|---|

| Cystic fibrosis | |

| Lack of industry partners | In 1999, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) adopted a “venture philanthropy” approach to share costs of early drug development. |

| Lack of clinical-trial expertise and infrastructure to conduct clinical trials | The CFF established the Therapeutic Development Program and clinical-trial networks in the United States, which now has 82 sites; the European Cystic Fibrosis Society Clinical Trial Network hosts 43 sites in 15 countries. |

| Limited efficacy outcome measures in young and minimally affected patients | Partner-supported efforts developed better physiological techniques (e.g., multiple breath washout) and imaging techniques (e.g., magnetic resonance imaging) in early lung disease. |

| Lack of patient and family input in clinical research process | CFF established patient and family advisory groups at care centers worldwide and developed initiatives (e.g., “I Am the Key”) to help educate patients and their families about clinical research and participation in clinical trials. |

| Lack of attention to the expectations of patients and their families | The CFF developed Web-based educational programs for patients and their families at www.cff.org. |

| Limited clinical-trial enrollment because of small patient population | The CFF formed a partnership with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop more efficient study designs that minimize study populations while ensuring patient safety; the Therapeutics Development Network (TDN) created a process for international study review and prioritization, in which research staff and patient representatives ensure that patients have access to the most effective trials. |

| Suboptimal study conduct that places patients at risk and that has a negative effect on drug development | The CFF established a continuous, transparent assessment of study metrics at all TDN and Clinical Trials Network sites, including times for study initiation and enrollment and deviations from protocol; the foundation also established a data and safety monitoring board to review all TDN therapeutic trials. |

| Expensive infrastructure for the drug-development and clinical-trial networks, resulting in high drug costs | Drug manufacturers adopted prices that reflect the clinical benefit and size of the market relative to development costs (e.g., approximately $300,000 annually for ivacaftor), with drug revenues fueling further investment in the development of multiple new treatments; eligible patients can access approved drugs through public and private programs that provide copayment assistance for insured patients and free medication for the uninsured. |

| Multiple myeloma | |

| Lack of collaboration among academic groups with expertise in clinical management and conduct of clinical trials | In 2004, the Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium (MMRC) was established as an outgrowth of the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation; the MMRC now has 22 sites. |

| Lack of a centralized, annotated tissue repository necessary for preclinical and correlative studies | The MMRC established a central tissue bank that now contains more than 3400 samples, with clinical follow-up leading to the genome sequencing of myeloma samples and other correlative study opportunities. |

| Need for more validated clinical targets developed from correlative studies | The MMRC developed clinical targets with support from trials conducted by the cooperative groups, including the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, the Southwest Oncology Group, and the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (now called the Alliance). |

| Prolonged start-up times for multicenter trials | All the academic centers in the MMRC agreed on a standard contract that leads to a 30% reduction in start time for trials conducted through the consortium. |

| Lack of communication among partners with the FDA about the most effective study designs and end points | The MMRC established a team-based approach with partners and the FDA to design more efficient study protocols and speed the development process. |

| Lack of common area for discussion and team-based global advances in this disease | The International Myeloma Foundation and the International Myeloma Working Group established global collaborations on guidelines. |

| High cost of sustaining infrastructure for therapeutic development | Drug manufacturers continue to seek a sustainable funding model for drug development. |

| Rising costs of new approved agents to target this disease | The MMRC and its partners encouraged a design for new trials with end points that do not lead to continuous therapy regimens; studies must show substantial clinical benefit to support drug approval and justify the additional costs to patients. |

| Type 1 diabetes mellitus | |

| Lack of industry initiatives for immunologic therapies for this disease | In the 1990s, groups that are sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — particularly, the Immune Tolerance Network (ITN) and T1D TrialNet — began to design, fund, and conduct proof-of-concept clinical trials of agents from partner pharmaceutical companies to catalyze clinical development. |

| Limited public awareness of this disease as an immunologic condition, distinct from type 2 diabetes, with opportunities for different therapies | Private nonprofit organizations (e.g., the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, and the American Diabetes Association) began to play an important role in public education and in bringing the experiences of patients and their families into the therapeutic development process. |

| Lack of sufficiently useful measures of efficacy as clinical end points | Academic networks and the NIH sponsored studies to improve the measurement of cellular, metabolic, and immunologic correlates of clinical benefit. |

| Need for combination therapy owing to the immunologic complexity in the disease mechanism | Drug manufacturers began to provide access to investigational drugs for use in T1D trials. |

| Requirement for thoughtful regulatory oversight for the testing of new drugs in children (the preferred target group in this disease) | Advocacy groups and T1D research networks began to push for changes in the policies of regulatory agencies that require proof of therapeutic benefit in adults before testing in children. |

| Need for data and sample sharing | Efforts by research networks and the NIH led to the development of accessible repositories and data portals, such as the ITN TrialShare resource at www.itntrialshare.org. |

| Higher costs for short-term biologic therapies than for insulin-replacement therapy | Advocacy groups and their partners began to encourage a cost–benefit analysis that includes financial savings associated with disease remission and the avoidance of long-term complications of diabetes. |

The development of the CFTR modulator ivacaftor (Kalydeco) illustrates the effect of this collaboration. Termed a potentiator, ivacaftor is a pharmacologic agent that increases the chloride-channel gating of CFTR that is regulated by protein kinase A. A potentiator is most effective in patients who have at least one copy of a class III mutation (e.g., CFTR G551D) that transports the CFTR to the cell surface but is defective as a chloride channel. In collaboration with the CFF, Vertex Pharmaceuticals discovered ivacaftor with the use of high-throughput screening that was originally designed by Aurora Biosciences and acquired by Vertex in 2001. Since the G551D mutation is carried by only approximately 2000 patients with cystic fibrosis worldwide, a multinational clinical development plan was required. Using a precision-medicine approach, Vertex was able to leverage an already genotyped patient population and an international cystic fibrosis community that was well poised to conduct the necessary clinical trials. This approach led to a rapid launch and enrollment of early and pivotal clinical trials, publication of results,23 and the approval of ivacaftor by the FDA in 2011 — a process that took only 4 years. Remarkably, the international, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial of ivacaftor involving patients 12 years of age and older23 was completed in only 19 months, from the first signing of informed consent to the completion of the trial by the last patient.

As has been the case with most other transformative therapies in rare diseases,24 the cost of ivacaftor is high25 (Table 1), yet most eligible patients have benefited from the drug as a result of public and private assistance programs to patients. The same development process permitted the approval of a combination of ivacaftor and lumacaftor (Orkambi) by the FDA in 2015. This combination drug corrects defects in both the CFTR protein trafficking and channel activation that are present in patients with two copies of the most common mutation, a deletion of three bases encoding a phenylalanine residue at position 508 (Phe508del).5 Regulatory approval of these two drugs resulted in substantial revenue (>$3 billion) for the CFF, which provides ongoing support for the development of future therapies for all patients with cystic fibrosis.

Successful collaborations require constant efforts to overcome barriers. For the cystic fibrosis community, these barriers and potential solutions are summarized in Table 1. Examples include developing an education program for patients and their families regarding participation in trials (e.g., “I Am the Key”) and developing better outcome measures for future clinical trials in younger and less symptomatic patients.

Multiple Myeloma

Patients with multiple myeloma, a cancer that is characterized by the growth of transformed plasma cells, present with infectious, skeletal, renal, and hematologic complications. Before 2000, the median overall survival among most patients was 3.5 years. In the intervening years, we have witnessed the approval of nine new drugs as well as an explosion in the understanding of the biologic features and genomic complexity associated with multiple myeloma.

Every year in the United States, approximately 25,000 patients receive a diagnosis of multiple myeloma, with 60,000 to 70,000 prevalent cases at any given time. The relatively low number of cases (as compared with diseases such as lung, colon, prostate, and breast cancer) limits the attraction for industry and the National Cancer Institute to initiate research projects. In addition, the pathway for drug approval has been less clear because of a lack of consistent treatment approaches and, more recently, a plethora of new treatment options, which has led many investigators and pharmaceutical companies to avoid translational research in multiple myeloma in favor of more common approval approaches. The opportunity to bring together academia with industry, the FDA, patients, and researchers from other disciplines to help solve problems in multiple myeloma was readily apparent (Fig. 1).

The Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium (MMRC) grew out of a patient advocacy group, the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF), in 2004. The original intent of the MMRC was to assemble a single group of core investigators who could validate preclinical models, form a central annotated tissue bank, and provide a common mechanism for rapid translation of laboratory findings into clinical trials. As the consortium began to grow, one of the early observations was the need for common contract language to allow for rapid integration of many sites (Table 1). This barrier was addressed through standard language for clinical-trial agreements. Armed with this central approach, the MMRC was ready to begin phase 1 and 2 trials of new agents or new combinations involving patients with relapsed myeloma.

As of this writing, more than 70 trials have been initiated within the consortium, with substantial input and enrollment for trials sponsored by industry. As an example, trials for the regulatory approval of both carfilzomib26 and pomalidomide27 (with accelerated approval on the basis of phase 2 studies) were led by the MMRC from both an enrollment and intellectual perspective. In addition, the initial phase 1b trials of the monoclonal antibody elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone28 or with bortezomib and dexamethasone29 were performed on the basis of preclinical scientific findings developed at MMRC sites, and trials were conducted by the MMRC.

Although not all the trials led to drug approval, early decisions about trial initiation were made, which reduced the time and expense associated with conducting additional early-phase trials. For example, early work with the HSP90 inhibitor ganetespib (STA-9090, which inhibits the activity of the HSP90 heat shock protein) did not show much clinical activity alone or in combination with bortezomib, so further study of the drug was abandoned. In contrast, a phase 1b trial of elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone showed striking efficacy, which led to trials that resulted in FDA approval of this agent despite the lack of single-agent activity. Much of this work resulted from the team-based approach that the MMRC had established with industry, the FDA, and the MMRF to develop the most efficient pathway for approval of new treatment options for patients with multiple myeloma. In another tack, the oncology cooperative groups (the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network, the Southwest Oncology Group, the Cancer and Leukemia Group B [now called the Alliance], and the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network) have focused on postapproval studies to identify the appropriate use of approved drugs in daily practice.30,31

The MMRC tissue bank was established to provide genome-sequencing data needed for target discovery and risk stratification. In the first 10 years of the MMRC (with major support from the MMRF), more than 3400 samples were submitted to the consortium. This large data set led to the initial genome sequencing of samples obtained from patients with multiple myeloma32 and subsequently enabled the creation of the Relating Clinical Outcomes in Multiple Myeloma to Personal Assessment of Genetic Profile (CoMMpass) clinical study,33 a prospective observational study in which patients are undergoing initial and subsequent in-depth molecular profiling. As of January 2017, this study had enrolled more than 1000 patients and had provided findings from genomic analyses and clinical follow-up, data that are publicly available for investigators regardless of their participation in the trial or membership in the MMRC.

In aggregate, the impetus for the MMRC — the need to have common tissue collection and access and to bring investigators together with clinical, laboratory, and trial experience in a rare disease — has resulted in rapid advancement of treatment options for patients. In addition, through close interactions and roundtables with the FDA, the MMRC has been able to help advise industry on approaches for regulatory trial design, which has contributed to the approval of nine agents for the treatment of multiple myeloma during the past 15 years. At this time, ongoing challenges include the funding model for clinical trials, particularly those with expensive genomic analyses and correlative studies that are required in current drug development, as well as increasing the burden of paperwork associated with regulatory requirements, which challenges normal clinical workflow and adds to the cost of conducting trials (Table 1). Although it has been challenging to secure funds for correlative studies in the past, the current environment of precision medicine and immunotherapy has raised the interest level by industry to fund these studies.

Type 1 Diabetes

In the early 1980s, treatment strategies for type 1 diabetes entered a new era that was catalyzed by the understanding that this disease was an autoimmune disorder resulting in selective destruction of insulin-secreting pancreatic islet beta cells.34 Several clinical trials of immune intervention have shown partial interruption of disease progression. Such findings have served as proof of concept for therapy directed at the underlying autoimmunity, even though these beneficial effects have been transient and the search for new treatments continues. Although the autoimmunity in type 1 diabetes often evolves over months or years preceding overt hyperglycemia, the clinical diagnosis of the disease corresponds to a critical period of beta-cell loss, which constitutes a window of opportunity for therapeutic intervention. However, most pharmaceutical companies have chosen not to prioritize immune therapy to prevent or to halt islet-cell damage in early type 1 diabetes in their clinical-trial portfolios, since the prevalence of the condition is only 0.4% in the United States and Europe and current insulin-replacement therapy is effective at restoring partial metabolic control. To fill this gap, an efficient translational ecosystem has been established that encompasses public advocacy, academic science, federal initiatives, and disease-related foundations, a collaboration that has enabled the conduct of numerous trials of new therapeutic agents that are designed to interrupt disease progression by blocking autoimmunity.

The roles of the partners in this ecosystem are shown in Figure 1. At the core are patients with type 1 diabetes and academic networks, supported by the NIH, which provide centers for patient enrollment and clinical-trial operations, together with strong academic leadership groups responsible for study design and analysis. Study concepts originate within the networks. Pharmaceutical companies are then invited to participate through providing drugs for testing in the trials, although the companies customarily have little role in the study design, conduct, or analysis. The use of skilled clinical sites and a prioritized ranking of experimental therapies ensure efficient and focused use of resources. An important element in enabling study enrollment is public education and advocacy, which among patients with type 1 diabetes is greatly helped by groups such as the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the American Diabetes Association, and the Helmsley Charitable Trust (Table 1). The costs of participating in studies of type 1 diabetes and paying for the associated drugs are not covered by any insurance carriers in the United States, and charitable organizations have helped to mitigate the costs by providing supplemental financial support to the networks or support for ancillary laboratory studies.

This closely integrated ecosystem is not without its challenges. Pharmaceutical companies may be reluctant to cede oversight over their experimental agents or lack incentive to pursue a so-called small market of patients with type 1 diabetes. And the research field has had additional challenges from several unsuccessful trials, although a recent example provides a case study in the utility of the collaborative partnership model. In this clinical trial, a combination of rapamycin (sirolimus) and interleukin-2 was administered to patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes.35 Trial enrollment was terminated after only nine patients had been treated because of an alarming decline in beta-cell secretory function — the opposite of what had been observed in preclinical studies in mice.36 Analysis of immune responses in the trial identified inadvertent activation of effector lymphocyte populations that probably accelerated the disease process, with transient beneficial effects on immune regulation. These findings were quickly publicized through professional conferences and publications,37 which led to rapid developments in four areas. First, investigators conducted new trials of agents that were specifically designed to delete these effector cells — for example, the T1DAL trial, in which beta-cell function was preserved and hypoglycemic events were reduced.38,39 Second, new immunomonitoring tools were developed to measure the ratio of effector T cells to regulatory T cells, which provided a new immune measurement to evaluate drug safety and mechanisms in future studies.40 Third, several pharmaceutical companies and some academic centers expanded their research to develop safer versions of interleukin-2 (called interleukin-2 muteins), which are projected to have a larger margin of safety owing to selective targeting properties.41 Fourth, the Immune Tolerance Network and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation established a preclinical research consortium, which developed a multicenter protocol for more robust validation testing in mice.42

These four advances not only corrected gaps in the field but also helped strengthen data-sharing ties among academic networks, funders, and industry (Table 1). Each of these partners benefited from the linked relationships that supported coordination of the next drug-development steps and plans for new trial strategies. Instead of slowing progress, the challenges presented by the unsuccessful trial of rapamycin and interleukin-2 actually focused a coordinated redirection of partnership effort — an outcome that would not have been possible without strong relationships in the type 1 diabetes community.

Conclusions

As these three disease-specific examples demonstrate, collaborations among complementary partners that are focused on a common goal have helped to bridge the preclinical phase to early human research trials and led to major advances in each field. These collaborations, among different foundations, academic centers, federal agencies, industry, and advocacy groups, have accomplished this success with the goal of improving outcomes for patients. For decades, a siloed mentality has hindered scientific and clinical-therapy development, but recent advances in clinical tools and science have necessitated larger collaborations. In an era of reduced federal funding for basic and preclinical research and drug development (coupled with a higher bar for regulatory compliance), the challenges continue to remain daunting and require new and collaborative approaches for ongoing success. In each of the cited cases, none of the major advances could have occurred in a timely manner if the partners had worked independently. Advocacy groups and foundations are finding creative ways to synergize the efforts of many partners to accelerate progress. Funding approaches that sustain these new models remain a challenge, but with powerful collaborations as the drivers and the success noted in these three examples, there is now precedent to continue to foster and support innovative partnerships.

Acknowledgments

We thank R.J. Beall and P.W. Campbell of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for their review of an earlier version of the manuscript and D. Auclair, J. Levy, and A. Quinn Young of the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation for reviewing an earlier version of the manuscript and providing data.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–21. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green ED, Watson JD, Collins FS. Human Genome Project: twenty-five years of big biology. Nature. 2015;526:29–31. doi: 10.1038/526029a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wainwright CE, Elborn JS, Ramsey BW. Lumacaftor-ivacaftor in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for Phe508del CFTR. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1783–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1510466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins FS. Reengineering translational science: the time is right. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:90c. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler D. Translational research: crossing the valley of death. Nature. 2008;453:840–2. doi: 10.1038/453840a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:301–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanson S, Nadig L, Altevogt B, editors. Venture philanthropy strategies to support translational research: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science. 1989;245:1073–80. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245:1066–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2475911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riordan JR. CFTR function and prospects for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:701–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Database. 2011 ( http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/app)

- 14.Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Molecular mechanisms of CFTR chloride channel dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 1993;73:1251–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90353-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson LG, Olsen JC, Sarkadi B, Moore KL, Swanstrom R, Boucher RC. Efficiency of gene transfer for restoration of normal airway epithelial function in cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 1992;2:21–5. doi: 10.1038/ng0992-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey BG, Leopold PL, Hackett NR, et al. Airway epithelial CFTR mRNA expression in cystic fibrosis patients after repetitive administration of a recombinant adenovirus. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1245–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI7935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welsh MJ. Gene transfer for cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1165–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI8634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verkman AS, Galietta LJ. Chloride channels as drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:153–71. doi: 10.1038/nrd2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, et al. Rescue of DeltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L1117–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00169.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins RF, LaMontagne S, Kazan B. Vertex Pharmaceuticals and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation: venture philanthropy funding for biotech. Harvard Business School Case 808-005. 2007 Oct; ( http://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=35037). (Revised July 2013.)

- 21.Ashlock MA, Olson ER. Therapeutics development for cystic fibrosis: a successful model for a multisystem genetic disease. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:107–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-061509-131034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe SM, Borowitz DS, Burns JL, et al. Progress in cystic fibrosis and the CF Therapeutics Development Network. Thorax. 2012;67:882–90. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1663–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Check Hayden E. Promising gene therapies pose million-dollar conundrum. Nature. 2016;534:305–6. doi: 10.1038/534305a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferkol T, Quinton P. Precision medicine: at what price? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:658–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1428ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siegel DS, Martin T, Wang M, et al. A phase 2 study of single-agent carfilzomib (PX-171-003-A1) in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;120:2817–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-425934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richardson PG, Siegel DS, Vij R, et al. Pomalidomide alone or in combination with low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 2 study. Blood. 2014;123:1826–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-538835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lonial S, Vij R, Harousseau JL, et al. Elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1953–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakubowiak AJ, Benson DM, Bensinger W, et al. Phase I trial of anti-CS1 monoclonal antibody elotuzumab in combination with bortezomib in the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1960–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.7069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Hofmeister CC, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1770–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapman MA, Lawrence MS, Keats JJ, et al. Initial genome sequencing and analysis of multiple myeloma. Nature. 2011;471:467–72. doi: 10.1038/nature09837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kowalski J, Dwivedi B, Newman S, et al. Gene integrated set profile analysis: a context-based approach for inferring biological endpoints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(7):e69. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eisenbarth GS. Type I diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1360–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605223142106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long SA, Rieck M, Sanda S, et al. Rapamycin/IL-2 combination therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes augments Tregs yet transiently impairs β-cell function. Diabetes. 2012;61:2340–8. doi: 10.2337/db12-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Shapiro AM, Rajotte RV, Power R. Combination therapy with sirolimus and interleukin-2 prevents spontaneous and recurrent autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2002;51:638–45. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long SA, Buckner JH, Greenbaum CJ. IL-2 therapy in type 1 diabetes: “trials” and tribulations. Clin Immunol. 2013;149:324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rigby MR, Harris KM, Pinckney A, et al. Alefacept provides sustained clinical and immunological effects in new-onset type 1 diabetes patients. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3285–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI81722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinckney A, Rigby MR, Keyes-Elstein L, Soppe CL, Nepom GT, Ehlers MR. Correlation among hypoglycemia, glycemic variability, and c-peptide preservation after alefacept therapy in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: analysis of data from the Immune Tolerance Network T1DAL trial. Clin Ther. 2016;38:1327–39. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckner JH, Nepom GT. Obstacles and opportunities for targeting the effector T cell response in type 1 diabetes. J Autoimmun. 2016;71:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bluestone JA, Crellin N, Trotta E. IL-2: change structure … change function. Immunity. 2015;42:779–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gill RG, Pagni PP, Kupfer T, et al. A preclinical consortium approach for assessing the efficacy of combined anti-CD3 plus IL-1 blockade in reversing new-onset autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2016;65:1310–6. doi: 10.2337/db15-0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]