Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association between chocolate intake and incident clinically apparent atrial fibrillation or flutter (AF)..

Methods

The Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study is a large population-based prospective cohort study. The present study is based on 55,502 participants (26,400 men and 29,102 women) aged 50–64 years who had provided information on chocolate intake at baseline. Incident cases of AF were ascertained by linkage with nationwide registries.

Results

During a median of 13.5 years, there were 3,346 cases of AF. Compared with chocolate intake less than once per month, the rate of AF was lower for people consuming 1–3 servings/month (Hazard Ratio [HR]= 0.90, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.82–0.98), 1 serving/week (HR= 0.83, 95% CI 0.74–0.92), 2–6 servings/week (HR= 0.80, 95% CI 0.71–0.91) and 1 servings/day (HR= 0.84, 95 %CI 0.65–1.09; p-linear trend<0.0001), with similar results for men and women.

Conclusions

Accumulating evidence indicates that moderate chocolate intake may be inversely associated with AF risk, though residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Nutrition, Atrial fibrillation, Prevention, Risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in clinical practice that affects 2.7 to 6.1 million people in the United States and 8.8 million in the European Union.[1] AF is associated with a higher risk of stroke, heart failure, cognitive decline, dementia and mortality [2] so identifying methods for preventing and identifying effective treatments for AF is of great public health importance.

Moderate consumption of cocoa and cocoa-containing foods may promote cardiovascular health due to their high content of flavanols, a subgroup of polyphenols with vasodilatory, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory benefits.[3, 4] There has been extensive research showing that moderate consumption of chocolate, particularly dark chocolate, improves markers of cardiovascular health [5] and is associated with a lower rate of myocardial infarction [6], heart failure [7, 8], composite cardiovascular adverse outcome, and cardiovascular mortality [9]. However, there is limited research on whether chocolate intake is associated with a lower rate of AF.”

Recent evidence suggests that the pathophysiology of AF involves an inflammatory cascade resulting in a release of cytokines, reactive oxygen species and stimulation of fibroblast proliferation, differentiation and activation.[10] Higher levels of inflammation may result in endothelial damage, increased platelet activation, and increased expression of fibrinogen that leads to electrical and structural remodeling of atrial tissue and thereby increase AF risk. [11] Therefore, we hypothesized that the anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet benefits of cocoa may be associated with a lower rate of AF.

We aimed to evaluate whether there is an association between chocolate intake and the rate of clinically apparent atrial fibrillation after adjusting for relevant confounders in a large prospective cohort study of men and women enrolled in the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study.

METHODS

study population

Between December 1993 and May 1997, the prospective Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study invited 160,725 individuals to participate. Inclusion criteria were 50 64 years of age, residence in the greater Copenhagen or Aarhus area and no previous cancer diagnosis in the Danish National Patient Register. At enrollment, anthropometric measurements were taken and biological materials were collected at one of the study centers; information on diet and lifestyle was obtained using self-administered questionnaires including a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Using the unique personal identification number (CPR number), we linked the cohort to the Danish National Patient Register to identify primary discharge diagnoses for atrial fibrillation or flutter (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision: I48) through December 2009. The study was approved by the regional Ethical Committees on Human Studies [jr.nr. (KF) 11 037/01] and [jr.nr. (KF) 01 045/93] and the Danish Data Protection Agency. All participants gave verbal and written informed consent.

chocolate intake

At baseline, participants completed a 192-item FFQ that was validated against two 7-day weighed diet records.[12, 13] Average intake of each food item during the last 12 months was reported in 10 categories from ‘never’ to ‘4–5 per day’. For each participant, average daily intake was calculated using the Food Calc software (version 1.3; J Lauritsen, University of Copenhagen; http://www.ibt.ku.dk/jesper/foodcalc/). Standard recipes and sex-specific portion sizes were applied to calculate intake in grams per day by using data from the 1995 Danish National Dietary Survey, 24-hour diet recall interviews from 3,818 of the study participants,[14] and several cookbooks. A serving of chocolate was defined as one-ounce, consistent with results of a validation study [15] that showed that the approximate serving size of chocolate in Swedish men is 30 g chocolate. The questionnaire did not differentiate between milk and dark chocolate, but most chocolate consumed in Denmark has a minimum of 30% cocoa solids.[16]

atrial fibrillation

All citizens of Denmark have a unique personal identification number that is used in all national registries, and updated information is available on emigration, hospitalizations and death. The Danish National Patient Register includes discharge diagnoses from in-hospital patients since 1977 and additional discharge diagnoses from emergency rooms and outpatient visits since 1995.

The outcome in this study was incident clinically apparent atrial fibrillation and/or atrial flutter (AFL) during the study period. Diagnoses were recorded using the Eighth International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8) until the end of 1993 (AF (427.93) and AFL (427.94) in the Danish version which is equivalent to AF or AFL (427.4) in the international version). From January 1994, the ICD-10 classification was used with the diagnosis of AF and/or AFL (I.48). The validity of the combined diagnosis of AF and/or AFL is high, with a positive predictive value of 92.6% in this cohort.[17] If a patient had both an emergency room visit and a hospital admission on the same date, only the in-hospital diagnosis was considered in order to avoid possible misclassification. In line with previous observational studies, the combined diagnosis of ‘AF and/or AFL’ was referred to as AF.

other covariates

We obtained information on demographics and lifestyle factors using a self-administered questionnaire. Body mass index, blood pressure and total cholesterol were measured by a lab technician at the time of recruitment.[18] We used self-reports, ICD codes and ATC (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical) drug codes to obtain information on prevalent and incident hypertension, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease (yes/no).[19]

statistical analysis

Individuals were considered at risk from the date of the study questionnaire (1993–1997) until the date of first hospital admission for AF, death, emigration, or end of follow-up (December 2009), whichever came first. Consistent with prior studies on chocolate intake and AF, we modeled chocolate intake using the following categories of servings of one-ounce bars or packets of chocolate: <1/month, 1 3/month, 1/week, 2–6/week and ≥1/day. We constructed multivariable Cox proportional hazards models with age as the time scale and allowed the baseline hazard to vary by sex to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between chocolate intake and the rate of atrial fibrillation. We chose covariates a priori[20] that we considered potential confounders on the basis of their association with development of atrial fibrillation: From the baseline data, we included information on sex, body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2), systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), total serum cholesterol (continuous), total calories (continuous), coffee consumption (continuous), alcohol consumption (grams/day), smoking status (never, former, current) and years of education beyond elementary school (0,<3, 3 4, >4 years). We used regularly updated information on hypertension (yes/no), diabetes mellitus (yes/no) and cardiovascular disease (yes/no) using time-varying covariates. Because there was no gradient in caffeine across categories of chocolate intake and it may be a consequence of chocolate intake, we did not include caffeine consumption as a covariate. We conducted tests of the linear component of trend for increasing categories of chocolate intake by assigning the median values for each category and testing the statistical significance of the term in the multivariable model.

To test the robustness of the model, we examined whether the HRs varied by sex, history of hypertension, diabetes or cardiovascular disease by conducting likelihood ratio tests to compare models with versus without cross-product terms for categories of exposure and the potential modifier. We constructed a multivariable model further adjusted for caffeine from sources other than chocolate (coffee, tea and soft drinks) instead of adjusting for coffee consumption. Since unrecognized illness may influence chocolate consumption at baseline, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding the first 2 years or 5 years of follow-up.

We tested the proportional hazard assumptions using Schoenfeld residuals and interactions with the logarithm of time, and we found no significant violations after allowing the baseline hazard to vary by sex. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 13, Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA) with 2-tailed tests set at α=0.05 for statistical significance.

RESULTS

danish diet, cancer, and health study

Among the 57,053 women and men recruited, we excluded participants for whom information was missing on chocolate intake (n=16), inclusion date (n=42) or one or more confounders (n=477). In addition, we excluded 1 participant with no FFQ, 451 participants with a previous record of atrial fibrillation in the Danish registry, and 564 participants who had a history of cancer at baseline (the primary outcome of the original cohort study). This resulted in a sample of 55,502 participants for these analyses. In total, 3,346 incident cases of AF occurred during a median of 13.5 years of follow-up. Overall, 36% of the sample was current smokers at baseline. Participants with higher levels of chocolate intake were more likely to report higher levels of daily caloric intake, a higher proportion of calories from chocolate and a higher level of educational attainment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the subjects in the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study according to frequency of chocolate intake, mean± standard deviation or median [interquartile range] or n (%)

| All Participants | <1/month | 1–3/month | 1/week | 2–6/week | ≥1/day | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 55502 | 12258 | 22909 | 10620 | 8476 | 1239 |

| Total calorie intake (kj/d) | 9841.3 ±2773.0 | 9041.8 ±2608.9 | 9582.6 ±2590.3 | 10180.8 ±2689.5 | 10932.8 ±2910.4 | 12155.8± 3328.7 |

| * Median [IQR] total calorie intake (kj/day) | 9546 [7901 – 11431] | 8790 [7224 – 10537] | 9312 [7746 – 11097] | 9871 [8341 – 11724] | 10632 [8922 – 12543] | 11629 [9768 – 13976] |

| Median [IQR] proportion of calories from chocolate (%) | 1.0 [0.4 – 1.9] | 0.2 [0.2 – 0.3] | 0.8 [0.5 – 1.1] | 1.7 [1.4 – 2.0] | 4.9 [4.1 – 6.1] | 10.6 [8.8 – 12.8] |

| † Caffeine consumption (mg/d) | 624.2 ±298.6 | 622.7 ±308.7 | 626.2 ±294.7 | 624.7 ±294.0 | 621.2 ±297.3 | 617.5± 316.7 |

| † Median [IQR] caffeine consumption (mg/d) | 620.6 [365.7 – 892.6] | 619.6 [362.7 – 892.1] | 621.3 [367.4 – 892.8] | 621.2 [374.7 – 892.9] | 621.4 [366.7 – 892.1] | 618.8 [366.7 – 892.5] |

| Coffee consumption (g/d) | 800.0 ±474.9 | 806.2 ±488.4 | 806.7 ±469.7 | 795.7 ±468.4 | 782.6 ±473.3 | 769.8± 499.4 |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | 20.5 ±21.9 | 22.7 ±25.3 | 20.1 ±21.2 | 19.4 ±20.1 | 20.1 ±20.4 | 19.0± 22.3 |

| Median [IQR] alcohol consumption (g/day) | 12.9 [5.9 – 31.1] | 13.0 [5.2 – 33.3] | 12.8 [6.0 – 30.5] | 12.8 [6.2 – 27.1] | 13.4 [6.3 – 30.5] | 12.1 [3.7 – 29.0] |

| Age at study entry (years) | 56.7 ±4.4 | 56.9 ±4.3 | 56.7 ±4.3 | 56.5 ±4.4 | 56.5 ±4.5 | 56.8± 4.6 |

| Sex (% men) | 26400 (47.6) | 5801 (47.3) | 10895 (47.6) | 5000 (47.1) | 4130 (48.7) | 574 (46.3) |

| Education (%) | ||||||

| ≤7 | 18309 (33.0) | 5072 (41.4) | 7899 (34.5) | 3013 (28.4) | 2017 (23.8) | 308 (24.9) |

| 8–10 | 25579 (46.1) | 5232 (42.7) | 10520 (45.9) | 5192 (48.9) | 4070 (48.0) | 565 (45.6) |

| ≥11 | 11614 (20.9) | 1954 (15.9) | 4490 (19.6) | 2415 (22.7) | 2389 (28.2) | 366 (29.5) |

| Body height (cm) | 170.1 ±8.9 | 169.4 ±8.8 | 170.0 ±8.8 | 170.3 ±8.9 | 171.0 ±8.9 | 170.7± 9.1 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.0 ±4.0 | 26.4 ±4.3 | 26.1 ±4.0 | 25.9 ±3.9 | 25.6 ±3.9 | 25.1± 3.9 |

| Smoking (%) | ||||||

| Never | 19480 (35.1) | 3653 (29.8) | 8266 (36.1) | 4061 (38.2) | 3102 (36.6) | 398 (32.1) |

| Former | 15931 (28.7) | 3528 (28.8) | 6672 (29.1) | 3001 (28.3) | 2378 (28.1) | 352 (28.4) |

| Current | 20091 (36.2) | 5077 (41.4) | 7971 (34.8) | 3558 (33.5) | 2996 (35.3) | 489 (39.5) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 139.5 ±20.5 | 141.4 ±21.2 | 139.6 ±20.4 | 138.8 ±20.2 | 137.8 ±19.8 | 137.1± 19.6 |

| Hypertension (%) | 9063 (16.3) | 2365 (19.3) | 3786 (16.5) | 1577 (14.8) | 1182 (13.9) | 153 12.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 1322 (2.4) | 666 (5.4) | 431 (1.9) | 127 (1.2) | 82 (1.0) | 16 1.3 |

| Cardiovascular disease (%) | 761 (1.4) | 243 (2.0) | 312 (1.4) | 115 (1.1) | 80 (0.9) | 11 0.9 |

| Total cholesterol > 6 mmol/L (%) | 27503 (49.6) | 6136 (50.1) | 11463 (50.0) | 5211 (49.1) | 4090 (48.3) | 603 48.7 |

IQR: interquartile range

Caffeine from sources other than chocolate (coffee, tea and soft drinks)

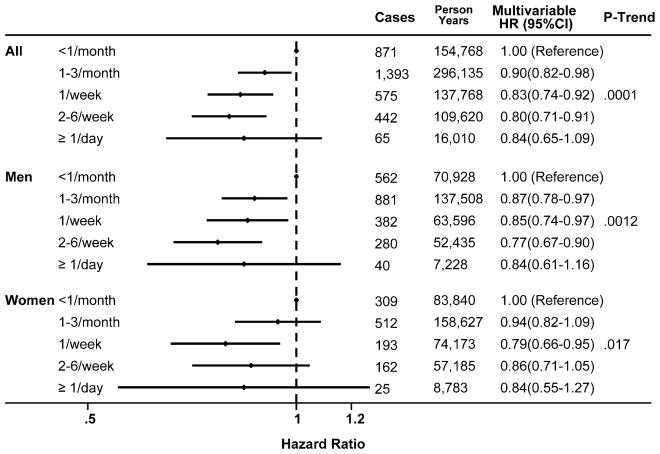

Compared with chocolate intake less than once per month, the rate of AF was lower for people consuming 1–3 servings/month (HR= 0.90, 95%CI 0.82–0.98), 1 serving/week (HR= 0.83, 95% CI 0.74–0.92), 2–6 servings/week (HR= 0.80, 95% CI 0.71–0.91) and ≥1 servings/day (HR= 0.84, 95%CI 0.65–1.09; p-linear trend<0.0001; Figure 1).

In analyses stratified by sex, the incidence rate of AF was lower among women than men at each level of chocolate intake, but the lower risk of AF with higher levels of chocolate intake was apparent for both men (p-linear trend=0.002) and women (p-linear trend=0.017) in the multivariable models accounting for several potential confounders (Figure 1). Among women, the strongest inverse association was seen for 1 serving of chocolate per week (HR= 0.79, 95% CI 0.66–0.95) and among men, the strongest inverse association was seen for 2 to 6 servings of chocolate per week (HR= 0.77, 95%CI 0.67–0.90).

Figure 1.

Multivariable hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) according to frequency of chocolate intake in the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study

P-trend is the value for linear component of trend

Age was the time scale in the Cox models and we adjusted for total calories, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), total serum cholesterol (continuous), coffee consumption (continuous), alcohol consumption (grams/day), smoking status (never, former, current), years of education beyond elementary school (0, <3, 3 4, >4 years), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes mellitus (yes/no) and cardiovascular disease (yes/no)

In sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the model, the results were similar across levels of history of hypertension (p-interaction=0.69) and cardiovascular disease (p-interaction=0.74). Although the results were different for the 284 individuals with diabetes (p-interaction=0.01), this was driven by the small number of individuals with diabetes that reported high levels of chocolate intake. The results were almost identical when we adjusted for caffeine from sources other than chocolate (coffee, tea and soft drinks) instead of adjusting for coffee consumption. The results were not meaningfully altered in analyses excluding the first 2 or 5 years of follow-up, suggesting that the results are not likely due to the potential impact of reverse causation.

DISCUSSION

In the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study, higher levels of chocolate intake were associated with an 11%–20% lower rate of clinically apparent AF among men and women. We adjusted for total caloric intake since a priori, we anticipated that it would be associated with the risk of AF and may confound the association. Since chocolate only contributes a small proportion of total calories, the results of the model do not imply that higher levels of chocolate intake results in substantially lower intake of other foods.

Two prior prospective cohort studies examined the association between chocolate intake and the rate of AF. Our results are consistent with results from the Women’s Health Study[21] that reported that moderate chocolate intake was associated with a 1%–14% lower rate of self-reported AF, though the estimates for each category of intake did not reach statistical significance. Conversely, results from the Physicians’ Health Study of men[22] did not find evidence of an association between chocolate intake and self-reported AF, and the point estimates suggested that higher levels of chocolate intake may be associated with a 4%–14% higher rate of self-reported AF, though the results did not reach statistical significance. In the current study, the lower rate of AF with higher levels of chocolate intake was apparent for both men and women.

There are several potential sources of heterogeneity across the studies. In this study, we identified cases of clinically apparent AF as a primary cause in the national registry whereas the prior two studies assessed the risk of self-reported AF verified in medical records. Based on the two prior studies, it may appear that the association varies by sex, but the results were similar for men and women enrolled in the Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Study. It is possible that the accuracy of self-reported chocolate intake or AF symptoms was different for the sample of women recruited from the general population in the Women’s Health Study compared to reporting by the physicians enrolled in the Physicians’ Health Study, but it is unclear how this would result in a systematic bias. It is also possible that the presence of potential confounding by factors related to chocolate intake and AF risk is different for the two samples, but this too is not clear or verifiable from the available data. Since chocolate in Europe has a higher cocoa content than chocolate in the US,[16] it is possible that our results were stronger than the results of the two US studies due to higher intake of potentially protective components of chocolate per serving.

Recent evidence suggests that an inflammatory cascade resulting in leukocyte activation may lead to generation of reactive oxygen species, proliferation of fibroblast and adverse turnover in matrix proteins. This may result in electrical and structural atrial remodeling, and lead to AF incidence. Cocoa’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-platelet properties may improve endothelial function, lipid levels, blood pressure, insulin resistance [23] and decrease fibrosis and downstream electrical and structural remodeling of atrial tissue.[10, 11] In addition, a typical 100 calorie serving of dark chocolate contains 36 mg of magnesium, which has hypotensive and antiarrhythmic effects.[24] These properties may explain the lower cardiovascular risk associated with moderate chocolate intake.

The higher flavonoid content of dark chocolate compared to milk chocolate may yield greater cardiovascular benefits. A randomized trial[25] found that, compared to milk chocolate, dark chocolate may have a higher caloric content but it also promotes greater satiety and lowers the desire to eat something sweet, resulting in an overall lower caloric intake. In addition, flavanol content and total antioxidant capacity in plasma may be lower if cocoa is consumed with milk or if cocoa is ingested as milk chocolate.[26] Furthermore, cocoa is usually consumed in high calorie products that use fat and sugar, and modern manufacturing of chocolate may result in losses of more than 80% of the original flavonoids from the cocoa beans.[27] Therefore, it may be advantageous to find ways to consume cocoa in forms other than chocolate bars. The ongoing Cocoa Supplement and Multivitamin Outcomes Study is a large randomized trial testing the effect of a concentrated cocoa extract on cardiovascular risk, and may provide insight on the efficacy and feasibility of ingesting cocoa in this form.

There are some limitations to our study that warrant discussion. Although we had extensive data on diet, lifestyle and comorbidities, we cannot preclude the possibility of residual or unmeasured confounding. For instance, data was not available on renal disease and sleep apnea. However, after adjusting for age, smoking status and other potential confounders, the association was somewhat attenuated but remained statistically significant. We did not have information on the type of chocolate or cocoa concentration. However, most of the chocolate consumed in in Denmark is milk chocolate. In the European Union, milk chocolate must contain a minimum of 30% of cocoa solids, and dark chocolate must contain a minimum of 43% cocoa solids; the corresponding proportions in United States are 10% and 35%.[16] Despite the fact that most of the chocolate consumed in our sample probably contained relatively low concentrations of the potentially protective ingredients, we still observed a robust statistically significant association, suggesting that our findings may underestimate the protective effects of dark chocolate.

As with any study using self-reported exposure information, there is a concern of poor recall. However, our FFQ was validated in a study comparing against two 7-day weighted diet records.[13] Furthermore, if the misclassification of chocolate intake was unrelated to AF incidence, our results would likely be an underestimate of the protective effect of chocolate. We have no information on how changes in chocolate consumption may have affected a participant’s risk of AF. Chocolate intake and covariate data were only available at baseline, and for most participants, in the fifth year of follow-up, and may have changed over the 13.5 years of follow-up, resulting in some non-differential misclassification of exposure, which would reduce the power to detect an association. In addition, this study was limited to cases with a diagnosis of AF as a primary cause. We did not have information on cases of silent AF, elective DC cardioversions, or AF reported in outpatient clinics and emergency room visits. Therefore, it is likely that we substantially underestimated the overall incidence of AF in the population. However, the restriction to diagnosed incident AF cases should not affect the validity of the current study since the identification of diagnosed symptomatic AF is unlikely to be impacted by levels of habitual chocolate intake. Finally, this study and the prior studies identified in our systematic review were primarily composed of Caucasian participants, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations if the association is modified by genetic factors.

Despite these limitations, our study has many strengths, including a large sample size, a prospective population-based design, detailed data on diet and factors potentially related to exposure and outcome, and almost complete follow-up of the study cohort over many years.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, participants with higher levels of chocolate intake had a lower rate of clinically apparent incident AF or flutter. Future research is necessary to confirm this finding and to determine whether high levels of chocolate intake are associated with higher AF risk.

KEY MESSAGES.

What is already known about this subject?

Several studies have reported cardiovascular benefits of chocolate intake but only two studies with discrepant findings have examined the association between chocolate intake and risk of atrial fibrillation.

What does this study add?

In this large prospective cohort study, we found that compared to individuals reporting chocolate intake less than once per month, the rate of AF was lower for people consuming chocolate regularly, with similar results for men and women.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Chocolate intake may be inversely associated with AF risk. Therefore, dark chocolate may be a healthy snack option that helps to prevent the development of AF.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was conducted with support from a grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL-115623), the European Research Council (ERC), EU 7th Research Framework Program (281760), a KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award (an appointed KL2 award) from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award KL2 TR001100) and the Danish Cancer Society and the Danish Council for Strategic Research (Aalborg AF-Study Group). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the European Research Council, Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or nonexclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in HEART editions and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights.

CONTRIBUTORS

KO is responsible for the overall content as a guarantor, contributed to the conception and design of the work, acquisition and interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; EM contributed to the conception and design of the work, interpretation of data for the work, and drafting of the manuscript; MBJ conducted the analysis and contributed to the interpretation of data and revising the manuscript; AT contributed to the conception or design of the work and the acquisition of data for the work; HSC revised the manuscript; MAM contributed to the conception and design of the work, interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and have agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflicts of Interest: None

COMPETING INTERESTS

None

ETHICS APPROVAL

The study was approved by the regional Ethical Committees on Human Studies [jr.nr. (KF) 11 037/01] and [jr.nr. (KF) 01 045/93] and the Danish Data Protection Agency. All participants gave verbal and written informed consent.

Role of the Sponsor: No funding organization had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection; management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Mostofsky, Email: elm225@mail.harvard.edu.

Martin Berg Johansen, Email: martin.johansen@rn.dk.

Anne Tjønneland, Email: annet@cancer.dk.

Harpreet S. Chahal, Email: hchahal3@uwo.ca.

Murray A. Mittleman, Email: mmittlem@hsph.harvard.edu.

Kim Overvad, Email: ko@ph.au.dk.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahman F, Kwan GF, Benjamin EJ. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2016;13:501. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu Y, Lambert JD. Modulation of metabolic syndrome-related inflammation by cocoa. Molecular nutrition & food research. 2013;57:948–61. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goya L, Martin MA, Sarria B, et al. Effect of Cocoa and Its Flavonoids on Biomarkers of Inflammation: Studies of Cell Culture, Animals and Humans. Nutrients. 2016;8:212. doi: 10.3390/nu8040212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higginbotham E, Taub PR. Cardiovascular Benefits of Dark Chocolate? Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 2015;17:54. doi: 10.1007/s11936-015-0419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsson SC, Akesson A, Gigante B, et al. Chocolate consumption and risk of myocardial infarction: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2016;102:1017–22. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostofsky E, Rice MS, Levitan EB, et al. Habitual coffee consumption and risk of heart failure: a dose-response meta-analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:401–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.967299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrone AB, Gaziano JM, Djousse L. Chocolate consumption and risk of heart failure in the Physicians’ Health Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2014;16:1372–6. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwok CS, Boekholdt SM, Lentjes MA, et al. Habitual chocolate consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease among healthy men and women. Heart (British Cardiac Society) 2015;101:1279–87. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedrichs K, Klinke A, Baldus S. Inflammatory pathways underlying atrial fibrillation. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu YF, Chen YJ, Lin YJ, et al. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2015;12:230–43. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Overvad K, Tjonneland A, Haraldsdottir J, et al. Development of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire to assess food, energy and nutrient intake in Denmark. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:900–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Haraldsdottir J, et al. Validation of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire developed in Denmark. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:906–12. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slimani N, Deharveng G, Charrondiere RU, et al. Structure of the standardized computerized 24-h diet recall interview used as reference method in the 22 centers participating in the EPIC project. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1999;58:251–66. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(98)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messerer M, Johansson SE, Wolk A. The validity of questionnaire-based micronutrient intake estimates is increased by including dietary supplement use in Swedish men. The Journal of nutrition. 2004;134:1800–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.7.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khodorowsky K, Robert H. The Little Book of Chocolate. Luçon, France: Flammarion ; London: Thames & Hudson; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rix TA, Riahi S, Overvad K, et al. Validity of the diagnoses atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in a Danish patient registry. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2012;46:149–53. doi: 10.3109/14017431.2012.673728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tjonneland A, Olsen A, Boll K, et al. Study design, exposure variables, and socioeconomic determinants of participation in Diet, Cancer and Health: a population-based prospective cohort study of 57,053 men and women in Denmark. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:432–41. doi: 10.1080/14034940601047986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lip GYH, Rasmussen LH, Skjøth F, et al. Stroke and mortality in patients with incident heart failure: the Diet, Cancer and Health (DCH) cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012:2. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller JD, Aronis KN, Chrispin J, et al. Obesity, Exercise, Obstructive Sleep Apnea, and Modifiable Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conen D, Chiuve SE, Everett BM, et al. Caffeine consumption and incident atrial fibrillation in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:509–14. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khawaja O, Petrone AB, Kanjwal Y, et al. Chocolate Consumption and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation (from the Physicians’ Health Study) Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:563–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooper L, Kay C, Abdelhamid A, et al. Effects of chocolate, cocoa, and flavan-3-ols on cardiovascular health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95:740–51. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.023457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz DL, Doughty K, Ali A. Cocoa and chocolate in human health and disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2011;15:2779–811. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen LB, Astrup A. Eating dark and milk chocolate: a randomized crossover study of effects on appetite and energy intake. Nutr Diabetes. 2011;1:e21. doi: 10.1038/nutd.2011.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serafini M, Bugianesi R, Maiani G, et al. Plasma antioxidants from chocolate. Nature. 2003;424:1013. doi: 10.1038/4241013a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Payne MJ, Hurst WJ, Miller KB, et al. Impact of fermentation, drying, roasting, and Dutch processing on epicatechin and catechin content of cacao beans and cocoa ingredients. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:10518–27. doi: 10.1021/jf102391q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]