Abstract

Retrieval-mediated learning is a powerful way to make memories last, but its neurocognitive mechanisms remain unclear. We propose that retrieval acts as a rapid consolidation event, supporting the creation of adaptive hippocampal-neocortical representations via the “online” reactivation of associative information. We describe parallels between online retrieval and offline consolidation, and offer testable predictions for future research.

Keywords: Long-term memory, episodic memory, testing effect, retrieval-mediated learning, consolidation, sleep, reactivation, replay

For over a century, psychologists have known that repeatedly and actively retrieving information from memory, as opposed to re-studying the same information, strongly enhances long-term retention [1]. The benefits of retrieval-mediated learning (also known as the ‘testing effect’) hold across a wide variety of materials and testing formats and remain evident across much of the life span [1]. No mechanistic framework exists to date integrating these behavioral findings with the growing literature on the neural basis of learning and memory [1]. Here we attempt such an explanation.

In short, we propose that retrieval acts as a fast route to memory consolidation. Specifically, we propose that retrieval integrates the memory with stored neocortical knowledge and differentiates it from competing memories, thereby making the memory less hippocampus-dependent and more readily accessible in the future. We will explore theoretical links between retrieval and offline consolidation, describe some key evidence in support of a shared mechanism, draw parallels between this proposal and other forms of rapid consolidation, and outline predictions for future research (see Box 1).

Box 1. Predictions and open questions for future research.

Human fMRI studies should find a relative increase of vmPFC and decrease of hippocampal contributions when probing previously retrieved compared with restudied memories.

Retrieval benefits (i.e., testing effects) should be associated with representational differentiation and competitor weakening [5].

Offline reactivation can occur spontaneously, but can also be induced by presenting cues previously paired with learning [in a technique known as targeted memory reactivation (TMR)] [4]. As cognitive control is absent during sleep, does TMR result in co-activation of related associations in a manner resembling retrieval during wake [5]?

If repeated reactivations via retrieval help to embed memories in neocortex and make them less hippocampus-dependent, this transformation should have observable effects on behavior. For example, retrieval, like sleep, should promote insight, inference and generalization, more so than restudy [4], and may reduce context-dependency during future recall.

Interactions between hippocampus and neocortex should be most effective when capitalizing on pre-existing neocortical schemas [13]. If retrieval-mediated learning depends on such interactions, its benefits will be reduced for novel materials that do not have pre-existing neocortical representations (e.g., nonsense drawings or syllables).

Retrieval as a rapid consolidation event

Extensive evidence from rodents and amnesic patients shows hippocampal damage affects the formation of new declarative memories while leaving remote memories (at least partially) intact [2]. An influential computational model [Complementary Learning Systems (CLS)] [2] suggests that hippocampus and neocortex act synergistically to allow for new learning while preserving old information. Specifically, the neocortex learns slowly and specializes in storing the statistical structure of experiences. The hippocampus learns quickly, and specializes in rapidly encoding and binding together new cortical associations. Repeated interactions between the two systems allow new information to slowly shape neocortical representation. If the hippocampus is damaged before enough hippocampal-neocortical interactions can occur, long-term memory will be impaired. These ideas constitute systems-level consolidation, or the process by which newly acquired information is transformed into a stable long-term memory representation [3].

The gradual transformation that a memory undergoes during systems-level consolidation is promoted by the memory’s repeated offline reactivation (‘replay’) in hippocampal-neocortical circuits. Reactivations during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep arguably play a unique role for embedding information in neocortex, facilitated by low cholinergic activity and coordinated oscillatory interactions between hippocampus and neocortex [4]. Replay occurring during both post-learning wakeful rest and sleep has been shown to enhance memory retention [3,4]. Critically, we propose that the neural reactivation of recently acquired memories, as triggered online by incomplete reminders (pattern completion), promotes long-term retention in a way similar to offline replay.

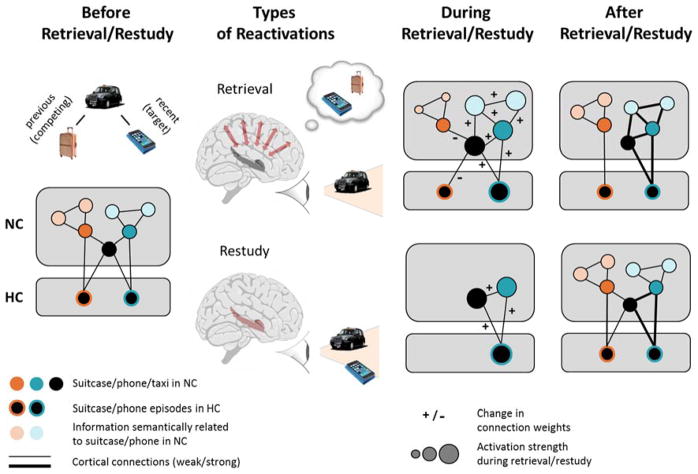

We argue that retrieval and sleep can qualitatively transform memories in at least two distinct ways: by integrating new memories into pre-existing neocortical knowledge structures, and by adaptively differentiating memories (i.e., reducing their neural overlap) such as to minimize competition between overlapping memories. From a computational perspective, both the integration and differentiation effects can be explained by the tendency of retrieval to be imprecise, that is, to co-activate memories that are semantically or episodically linked to the target memory [5]. Repeated imprecise reactivations in hippocampal-neocortical circuits afford an opportunity to integrate an initially hippocampus-dependent memory into the co-activated neocortical knowledge structures, similar to replay events during NREM sleep (see Fig. 1). According to [5], the nature of learning driven by co-activation depends on how strongly memories are activated: Strong co-activation of memories leads to integration of those memories, whereas moderate activation of competing memories triggers their adaptive weakening [6] and pushes retrieved and competing memories apart in representational space [7], leaving the retrieved memory in a distinct, accessible state for future recall (see Fig. 1). Importantly, restudy, i.e. simple re-exposure to a complete, previously stored memory, does not share these computational characteristics [6,7]. Restudy may re-impose the memory’s original pattern onto hippocampus and neocortex, causing some strengthening of the original trace. However, because restudy triggers less co-activation of related memories, it does not adaptively shape the hippocampal-neocortical memory landscape in the same way as active retrieval.

Figure 1. Neural network changes via retrieval compared to restudy.

Imagine you form a new memory of leaving your phone in a taxicab. Also imagine that two weeks prior to this episode, you needed a taxi because you had a very heavy suitcase with you. The two episodes have distinct, non-overlapping representations in hippocampus (HC) but are connected via the shared element “taxi” in neocortex (NC). NC also holds representations of memories that are loosely connected with phones and suitcases, respectively. Retrieval of the taxi-phone episode will activate the core representations in HC and NC, but it will also cause co-activation of related information including the suitcase, and knowledge related to phones. Strongly active memories and their connections (blue elements) will be strengthened, supporting memory integration. Moderately co-activated information will be weakened, supporting differentiation, while no change in connection strength occurs for weakly active memories. In comparison, restudy re-instantiates the cortical representations only of those elements that are explicitly presented; connections between these elements will be strengthened, but the memory will not be integrated with or differentiated from other stored knowledge.

So far, we have outlined the similarities between retrieval and offline consolidation on a theoretical, computational level. We will next examine behavioral and neural parallels between memory retrieval effects (indexed by differences in retrieved vs. re-studied information) and consolidation effects (indexed by sleep vs. wake intervals) that empirically support our rapid consolidation view.

Similarities between retrieval and consolidation

If retrieval rapidly embeds a memory in neocortex, future retrievals of this memory can utilize neocortical in addition to hippocampal representations to access the memory. Retrieval-mediated memory boosts should thus be most evident whenever hippocampal traces are weak and recall is relatively more dependent on neocortex. Consistent with this notion, testing effects are strongest at long delays of several days to weeks [1], when recall supposedly relies more heavily on neocortical traces than at short delays.

Online retrieval and offline reactivation also share the property of protecting memories from retroactive interference. Including a period of sleep (as opposed to wake) between two learning sessions reduces retroactive interference [3], presumably due to offline reactivation. Intriguingly, including retrieval practice between learning two lists of words similarly reduces retroactive interference [8], consistent with a rapid online consolidation mechanism.

Sleep has been shown to globally enhance long-term retention, but seems to preferentially benefit salient, rewarded, or emotional information containing future utility [3,4]. Assuming that prioritized information is “tagged” to receive greater offline processing during sleep, retrieval could in theory interact with the consolidation process in two different ways. If retrieval effectively tags information to receive greater subsequent offline processing during sleep, retrieved memories should benefit more from sleep than restudied memories. On the other hand, if the benefits of retrieval occur online, as proposed by our rapid consolidation framework, sleep should offer greater relative benefits to restudied information because retrieved information has already been consolidated online. Indeed, restudied information benefits more from sleep than retrieved information [9], underscoring the idea that sleep offers relatively more benefits to information that has not already been stabilized via online consolidation during retrieval.

Systems consolidation accounts [2] state that initially hippocampus-dependent memories become gradually incorporated into neocortex for stable long-term storage. If retrieval speeds up consolidation, it should produce similar neural changes as offline consolidation. In humans, connectivity between the hippocampus and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), a key region in systems consolidation, increases after sleep [11] and retrieval practice, but not after restudy [12]. Similarly, it has been shown in rodents that repeated reactivations support the creation of memory traces that can be accessed independently of the hippocampus [10], suggesting online reactivation resembles offline consolidation at a neural level.

Can neocortical representations be modified rapidly?

While most frameworks propose that systems consolidation happens slowly via hippocampal-neocortical interactions over time [2], we propose retrieval promotes the rapid development of neocortical representations without time and sleep. Importantly, two other learning paradigms suggest that rapid cortical learning is possible. First, research on schema-based learning demonstrates that information consistent with prior knowledge (schemas) can become hippocampus-independent and embedded in neocortex surprisingly quickly and without intervening sleep [13]. As argued above, we assume that retrieval rapidly consolidates memories in a similar way, by co-activating related knowledge structures to facilitate neocortical integration.

Second, in a related paradigm called “fast mapping”, individuals rely on prior knowledge to learn new information by active inference [14]. Intriguingly, patients with hippocampal amnesia can learn new objects more effectively using fast mapping than a simple instruction to encode explicitly [14], suggesting fast mapping arises from a faster neocortical embedding process [15]. Associations learned via fast mapping (compared to explicit encoding) also benefit less from sleep [15], very similar to associations learned via active retrieval (compared to re-study) [9]. These findings imply that offline enhancement is reduced if cortical integration occurs online via fast mapping or retrieval. In fact, fast mapping and retrieval share the common elements of active inference and knowledge activation, and may thus exert their beneficial effects on long-term retention via the same mechanism.

Concluding Remarks

We propose that retrieval stabilizes memories via similar mechanisms that occur during sleep and offline consolidation periods. We acknowledge that sleep has unique characteristics that are not shared with wake retrieval modes. At the moment, it is unclear to what degree reactivations during sleep are imprecise and associated with the same strengthening and weakening dynamics as reactivations during wake. Nevertheless, the rapid consolidation view of retrieval makes testable predictions for future research (Box 1) and will hopefully stimulate new research to bridge the existing gap between cognitive and neuroscientific investigations of memory modification.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the CV Starr Fellowship (awarded to JWA), NIMH R01MH069456 (awarded to KAN), and by ESRC grant ES/M001644/1 (awarded to MW).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Rowland CA. The effect of testing versus restudy on retention: A meta-analytic review of the testing effect. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1432–63. doi: 10.1037/a0037559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClelland JL, et al. Why there are complementary learning systems in the hippocampus and neocortex: Insights from the successes and failures of connectionist models of learning and memory. Psychol Rev. 1995;102:419–57. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dudai Y, Karni A, Born J. The Consolidation and Transformation of Memory. Neuron. 2015;88:20–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antony JW, Paller KA. Hippocampal contributions to declarative memory consolidation during sleep. In: Hannula DE, Duff MC, editors. The Hippocampus from Cells to Systems. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norman KA, et al. A neural network model of retrieval-induced forgetting. Psychol Rev. 2007;114:887–953. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wimber M, et al. Retrieval induces adaptive forgetting of competing memories via cortical pattern suppression. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:582–9. doi: 10.1038/nn.3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulbert JC, Norman KA. Neural differentiation tracks improved recall of competing memories following interleaved study and retrieval practice. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:3994–4008. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potts R, Shanks DR. Can testing immunize memories against interference? J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2012;38:1780–5. doi: 10.1037/a0028218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bäuml KHT, et al. Sleep can reduce the testing effect: it enhances recall of restudied items but can leave recall of retrieved items unaffected. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2014;40:1568–1581. doi: 10.1037/xlm0000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehmann H, et al. Making context memories independent of the hippocampus. Learn Mem. 2009;16:417–20. doi: 10.1101/lm.1385409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gais S, et al. Sleep transforms the cerebral trace of. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:18778–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705454104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wing EA, et al. Neural correlates of retrieval-based memory enhancement: An fMRI study of the testing effect. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:2360–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tse D, et al. Schemas and memory consolidation. Science. 2007;316:76–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1135935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharon T, et al. Rapid neocortical acquisition of long-term arbitrary associations independent of the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:1146–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005238108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Himmer L, et al. Sleep-mediated memory consolidation depends on the level of integration at encoding. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;137:101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]