Abstract

The unaddressed palliative care needs of patients with advanced, nonmalignant, lung disease highlight the urgent requirement for new models of care. This study describes a new integrated respiratory and palliative care service and examines outcomes from this service.

The Advanced Lung Disease Service (ALDS) is a long-term, multidisciplinary, integrated service. In this single-group cohort study, demographic and prospective outcome data were collected over 4 years, with retrospective evaluation of unscheduled healthcare usage.

Of 171 patients included, 97 (56.7%) were male with mean age 75.9 years and 142 (83.0%) had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. ALDS patients had severely reduced pulmonary function (median (interquartile range (IQR)) forced expiratory volume in 1 s 0.8 (0.6–1.1) L and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide 37.5 (29.0–48.0) % pred) and severe breathlessness. All patients received nonpharmacological breathlessness management education and 74 (43.3%) were prescribed morphine for breathlessness (median dose 9 mg·day−1). There was a 52.4% reduction in the mean number of emergency department respiratory presentations in the year after ALDS care commenced (p=0.007). 145 patients (84.8%) discussed and/or completed an advance care plan. 61 patients died, of whom only 15 (24.6%) died in an acute hospital bed.

While this was a single-group cohort study, integrated respiratory and palliative care was associated with improved end-of-life care and reduced unscheduled healthcare usage.

Short abstract

Integrated respiratory and palliative care is associated with better end-of-life care for patients with advanced lung disease http://ow.ly/mgkn30hlPXV

Introduction

Palliative care aims to improve the quality of life of patients and their families when facing life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by controlling symptoms and addressing physical, psychosocial and spiritual issues [1]. Outcomes from palliative care include reduced hospital admissions and healthcare costs, less aggressive treatment, better symptom management, and improved survival [2–5]. Despite guidelines recommending specialist palliative care for patients with advanced lung disease [6–10], only 1.7% of patients with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the USA are referred to palliative care when admitted with an exacerbation [11]. Similarly, in Australia, only 17.9% of COPD patients access any palliative care in their last year of life [12, 13].

Well-described barriers to accessing palliative care include the difficulty prognosticating in chronic diseases such as COPD [10], patients' fears of abandonment by their usual physician [14], clinicians lacking time to discuss palliative care or being reluctant to take away hope [14] and concerns around overburdening already stretched palliative care services [15, 16]. These barriers highlight the need for new models of care, whereby the patient's usual respiratory clinician remains central to the integration of palliative care principles and practices into their patient's management [16–18]. This article describes one such integrated respiratory and palliative care model, and highlights key outcomes from a comprehensive review of this clinical service.

Methods

New model of care

The Advanced Lung Disease Service (ALDS) was established at The Royal Melbourne Hospital (Parkville, Australia) in April 2013 as a new, integrated respiratory and palliative care service. The ALDS runs in addition to usual respiratory medicine activities and is a multidisciplinary, specialist, single point-of-access service, based within a major Australian teaching hospital. The service provides both hospital and home-based care, and aims to offer long-term holistic care, individualised symptom management and disease optimisation, self-management education, and routine discussion of goals of care (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Advanced Lung Disease Service key components

| 1) | Respiratory and palliative care offered together, to provide individualised care which addresses the underlying respiratory disease, symptoms and psychosocial issues |

| 2) | Disease treatment optimisation including: optimising inhaler therapy and device technique, smoking cessation support, pulmonary rehabilitation referral, and domiciliary oxygen therapy assessment, education and management |

| 3) | Comprehensive management of refractory breathlessness, with nonpharmacological strategies (such as breathing techniques, recovery breathing positions, the use of a handheld fan) and opioids as required; individualised written breathlessness plans and written breathlessness resources provided |

| 4) | Self-management support including patient and family education regarding disease and symptom management, with provision of written exacerbation action plans |

| 5) | Routine discussions regarding goals of care and advance care planning |

| 6) | Patient- and family-focused care including extended 1-h consultations, urgent reviews and rapid access (<1 week) for new referrals as needed |

| 7) | Specific carer support including facilitating access to respite care and bereavement support |

| 8) | Long-term follow-up with continuity of care in clinic and nonabandonment |

| 9) | Telephone support and home visits provided by a respiratory nurse consultant |

| 10) | Early access to “Hospital in the Home” care to avoid respiratory admissions |

| 11) | Respiratory care and service coordination, and integration with other community services, including aged care assessment services |

| 12) | Focus on early communication with, and support of, general practitioners and other health professionals, including teleconferences |

Active breathlessness management is one focus of the ALDS, and includes educating all patients and accompanying carers regarding nonpharmacological self-management strategies such as breathing techniques, recovery breathing positions, activity pacing and the use a handheld fan. As breathlessness self-management education is an iterative process, education and reminders to adopt techniques are provided regularly during clinic or home visits. Additionally, after cautious evaluation of risks and potential benefits, opioids may be prescribed to patients with ongoing refractory breathlessness. Individualised written breathlessness plans, written breathlessness resources and handheld fans are provided to patients, with copies of written resources sent to patients' general practitioners (GPs). Similarly, there is a strong emphasis on identifying psychological comorbidities, which may contribute to breathlessness, and actively managing these issues by referral on to other health professionals such as psychologists (in the community or our dedicated ALDS psychologist) and/or initiation of appropriate medications.

Our philosophy is that both respiratory and palliative care should be initially introduced and primarily provided by the ALDS respiratory team, who have completed additional training in basic palliative care. However, all patients are offered an appointment with the palliative care team in the ALDS clinic and patients with challenging symptoms or more complex situations are offered regular review with the ALDS palliative care specialist, often as a co-consultation with the respiratory team.

The ALDS comprises a specialist clinic attended by respiratory medicine and palliative care clinicians, as well as a psychologist, a community outreach service with nurse-led home visits and telephone support, and a multidisciplinary team meeting attended by clinicians from respiratory medicine, palliative care, the emergency department, geriatrics, “Hospital in the Home” and clinical psychology. Additionally, the ALDS works closely with the hospital community respiratory team, which offers pulmonary rehabilitation, and also with community palliative care teams.

The ALDS accepts all referrals from primary care or other medical practitioners, for any patient, with severe, nonmalignant, respiratory disease. There are no set referral criteria, with referral instead being entirely at the discretion of the referring clinician. Either long-term, shared care with the primary care team or short-term care (for breathlessness management only) is offered. The initial assessment occurs in the ALDS clinic, with long-term care offered through both clinic and home visits. While follow-up is individualised according to needs, patients are generally offered routine ALDS clinic reviews every few months, or sooner if required. Additionally, patients may request an ALDS nurse consultant home visit at any time. When patients become too unwell to attend clinic, ALDS telephone support and home visits continue; however, patients are also offered referral to a community palliative care team, and telephone support is offered to GPs and other healthcare professionals.

Study design and data collection

In this single-group observational cohort study, all patients managed by the ALDS were eligible for inclusion. Patients were only excluded if they were referred but never seen. Data were collected initially as a retrospective medical record audit in November 2015 and then prospectively with weekly data collection for all ALDS patients going forwards. Data collected included patient demographics, respiratory diagnoses and severity, respiratory management (smoking cessation, respiratory vaccines, medications, pulmonary rehabilitation), symptom palliation management, specialist palliative care input, advance care planning activities, and mortality data. Data related to hospital admissions or emergency department presentations (not leading to admission) for a respiratory illness were collected retrospectively. When data were unavailable, the patient's GP was contacted to obtain additional information. Mortality data were confirmed by the Victorian Births, Marriages and Deaths Registry. Ethics approval was granted for this study by Melbourne Health.

Data analysis

Patient demographics are reported descriptively, using counts and frequencies. Median values are reported for variables with significant distribution skew. Time was measured in 28-day months. A “before and after” comparison was undertaken to examine any association between ALDS care and unscheduled healthcare usage in the 12 months before and after first ALDS review. 12 months was chosen because this was approximately the median length of survival of the cohort. The paired t-test was used to examine the three null hypotheses that there would be no difference in the mean number of hospital admissions, emergency department presentations (without admission) or length of stay for a respiratory illness in the year before ALDS care commenced compared with in the first year of ALDS care. As it was expected that not all patients would have 12 months of complete follow-up data after first review (due to death within that timeframe or recent referral), means for emergency department presentations, admissions and length of stay were calculated as person time (i.e. per patient per month). Any follow-up time after first ALDS contact was included, even if it was <12 months. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), with a p-value <0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

ALDS patient demographics

Over 4 years the ALDS was referred 185 patients, all of whom were accepted by the service. 14 patients were excluded from this analysis, having died before their first ALDS appointment. There was no loss of follow-up and minimal missing data.

Of the 171 patients included, 97 (56.7%) were male with a mean age of 75.9 years (table 2). 142 (83.0%) had COPD as their primary respiratory diagnosis and almost two-thirds had at least one other coexisting respiratory condition. ALDS patients had severely reduced pulmonary function, with a median (interquartile range (IQR)) forced expiratory volume in 1 s 0.8 (0.6–1.1) L and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide 37.5 (29.0–48.0) % pred, severely reduced 6-min walk test distance, and very significant hypoxaemia. Three-quarters of patients reported having very severe breathlessness, with a modified Medical Research Council Dyspnoea score of 3 or 4.

TABLE 2.

Patient characteristics and diagnoses

| Patients | 171 |

| Male | 97 (56.7) |

| Age years (mean (range)) | 75.9 (42.8–91.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 134 (78.4) |

| Lives alone | 45 (26.3) |

| Lives in nursing home | 19 (11.1) |

| Primary respiratory diagnosis | |

| COPD | 142 (83.0) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 14 (8.9) |

| Bronchiectasis | 7 (4.1) |

| Coexisting second respiratory condition | 107 (62.6) |

| Comorbidities (mean (range)) | 6.8 (0–14) |

| Anxiety | 65 (38.0) |

| Depression | 51 (29.8) |

| Cardiac disease | 119 (69.6) |

| Cardiac comorbidities (mean (range)) | 1.5 (0–5) |

| Pulmonary function n=169 | |

| FEV1 L (median (IQR)) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| FEV1 % pred (median (IQR)) | 41.5 (32.0–55.8) |

| FVC L (median (IQR)) | 2.2 (1.7–2.7) |

| FVC % pred (median (IQR)) | 83 (65.3–101.8) |

| DLCO (median (IQR)) | 8 (6–10) |

| DLCO % pred (median (IQR)) | 37.5 (29.0–48.0) |

| 6MWD on air m (median (IQR)) n=163 | 80 (0–222.5) |

| PaO2 mmHg (median (IQR)) n=115 | 57.1 (51.1–64.0) |

| PaCO2 mmHg (median (IQR)) n=115 | 45.0 (39.3–50.9) |

| Domiciliary oxygen use | 111 (64.9) |

| mMRC Dyspnoea scale score (median (IQR)) | 4 (2–4) |

| mMRC Dyspnoea scale score 1–2 | 48 (26.9) |

| mMRC Dyspnoea scale score 3–4 | 123 (73.1) |

Data are presented as n or n (%), unless otherwise stated. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; IQR: interquartile range; FVC: forced vital capacity; DLCO: diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance; PaO2: arterial oxygen tension; PaCO2: arterial carbon dioxide tension; mMRC: modified Medical Research Council.

ALDS activity

Most patients were referred as quaternary referrals from other hospital specialists, including 151 (88.3%) referrals from our General Respiratory Service. Patients were followed for a median (IQR) of 15.3 (8.1–33.9) months and had a median (IQR) of 5 (2–9) ALDS clinic visits. 137 patients (80.1%) were cared for long term or until death. The ALDS currently actively manages 87 patients. Patients were discharged on request, if they lived far outside the hospital catchment (seven patients (4.1%)) or received long-term care from another respiratory physician (six patients (3.5%)).

Breathlessness management

An 8-week community pulmonary rehabilitation programme was undertaken by 118 patients (69%) prior to ALDS involvement and by 61 patients (35.7%), either as a first or repeat pulmonary rehabilitation programme, while managed by the ALDS. 34 patients (19.9%) declined a first or repeat pulmonary rehabilitation referral. In addition to pulmonary rehabilitation, all patients received comprehensive breathlessness education regarding self-management, nonpharmacological strategies (as detailed earlier) and opioids, if required, from the ALDS team.

Oral opioids were recommended to 81 ALDS patients (47.4%) with refractory breathlessness, of whom 74 (43.3%) accepted, with 11 using opioids to treat both pain and breathlessness. The median dose prescribed for breathlessness was 12 mg·day−1, with the median actual opioid dose consumed being 9 mg·day−1 oral morphine equivalent.

31 out of the 74 patients (41.9%) prescribed morphine self-reported as being very compliant with morphine treatment and 28 patients (37.8%) experienced morphine side-effects, which were mostly gastrointestinal (constipation in 21 patients). Other side-effects included low mood (two patients (2.7%)), sedation (two patients (2.7%)) and hallucinations (two patients (2.7%)). Six patients (8.1%) subsequently stopped morphine due to side-effects and four patients (5.4%) stopped morphine due to lack of efficacy.

Acute emergency healthcare utilisation

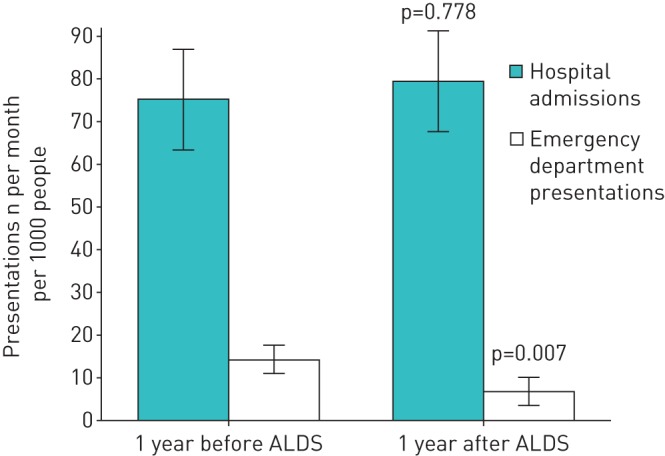

49 patients (28.7%), of whom 31 died, had <12 months of follow-up data. This group had a mean follow-up of 6.9 months. There was a 52.4% reduction in the mean number of emergency department respiratory presentations (not leading to admission) per month per 1000 people in the year after ALDS care commenced compared with the preceding year (p=0.007) (figure 1). This reduction in emergency department respiratory presentations was seen in patients both with and without anxiety and/or depression. However, there was no significant difference in the mean number of acute hospital admissions for a respiratory illness per month (75.2 admissions per month per 1000 people in the preceding year and 79.5 admissions per month per 1000 people in the year after ALDS involvement) or for adjusted length of stay (447.2 days per month per 1000 people and 445.5 days per month per 1000 people in the year after).

FIGURE 1.

Hospital admissions and emergency department presentations (without admission) for respiratory illness. Data are presented as mean±sem.

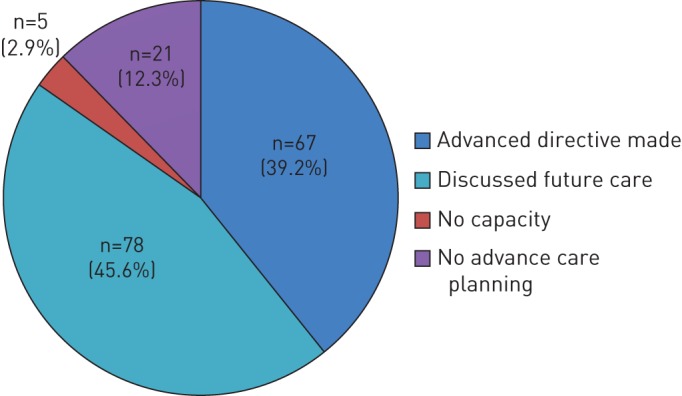

Advance care planning

The ALDS team regularly discussed advance care planning with 145 patients (84.8%) (figure 2). 67 patients (39.2%) made a written advance care directive, of whom only three had written this before referral to the ALDS. Patients who wished to discuss advance care planning with the ALDS team, but who did not wish to write a formal advance care planning directive, permitted these conversations to be recorded on a “record of advance care planning” card in their medical files. Of the 21 patients with whom advance care planning was not discussed, despite having capacity, 15 were seen in the clinic only once or twice. Additionally, two patients had significant psychological issues with depression or anxiety and therefore advance care planning discussions were deferred.

FIGURE 2.

Advanced Lung Disease Service advance care planning activities.

Access to specialist palliative care services

134 patients (78.4%) saw the palliative care physician or specialist registrar in the ALDS clinic, with 10 patients seeing both. Additionally, 49 patients (28.7%) were referred for community palliative care. Only seven patients (4.1%) declined referral to community palliative care.

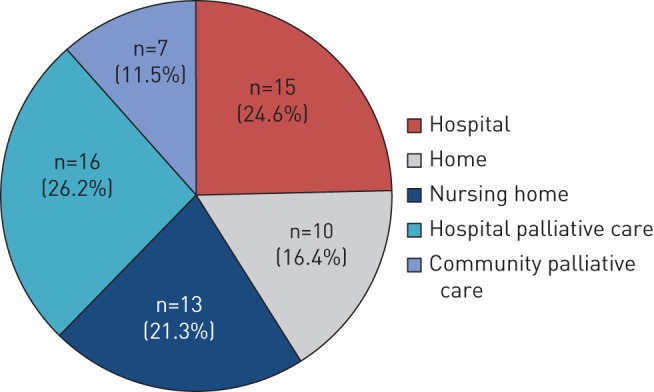

Mortality

61 ALDS patients (35.7%) died over the 4 years; 51 died from their primary long-term respiratory disease and one died from lung cancer. The remainder died from a nonrespiratory cause. The median (IQR) time to death from first ALDS clinic visit was 12.4 (7.8–27.1) months. Only 15 patients (24.6%) died in an acute hospital bed; the remainder died at home, in a nursing home or in a palliative care bed (figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Advanced Lung Disease Service patients' place of death.

Discussion

This is the first study to describe longer-term outcomes over 4 years for patients with advanced lung disease being cared for by an integrated respiratory and palliative care service. Compared with published outcomes for patients with severe lung disease receiving standard care [11, 13, 17, 19–23] and compared with our baseline data, end-of-life care in our cohort has improved through active management of refractory breathlessness, high levels of advance care planning, improved access to specialist palliative care and fewer hospital deaths. These improvements were achieved despite this patient cohort being of older age with severe lung disease and having multiple medical comorbidities, and significant psychological comorbidity.

Emergency healthcare utilisation

The reduction in emergency department visits (not leading to admission) identified in the “before and after” comparison of ALDS care is consistent with the findings of Rocker and Verma [24], who also demonstrated a 52% reduction in emergency department visits at 12 months in patients enrolled in the Canadian integrated service “INSPIRED”, which offers holistic care and care coordination to COPD patients. The reduction in emergency department visits identified in our study may reflect patients and their families having better self-management skills to address mild exacerbations and also to manage distressing breathlessness. However, as most COPD admissions are related to severe exacerbations or significant, persisting changes in disease status, it is more challenging to deliver interventions that successfully reduce actual hospital admission rates. Similarly, healthcare utilisation (especially hospital admissions) usually increases and is highest in the last year of life [25]. As the median survival of the ALDS cohort was 12.4 months, demonstrating that admissions do not increase in the following year may still represent a success. Additionally, this finding of an unchanged hospital admission rate may reassure health professionals and patients alike that care provided by an integrated respiratory and palliative care service (including increased completion of advance care planning) does not deny active treatment nor prevent ongoing access to inpatient care when required.

Advance care planning and place of death

Despite the importance of advance care planning for patients with COPD, this occurs infrequently. A review of 226 COPD patient deaths over 12 years up to 2015 at our institution demonstrated that only 14.6% discussed advance care planning prior to their death, of whom just 11 patients (4.9%) wrote an advance care planning directive [26]. However, in the ALDS cohort, advance care planning participation was extremely high. This may be associated with the routine practice of asking all ALDS patients if advance care planning can be discussed and providing extended consultations to facilitate this. Likewise, in a randomised control trial examining a new hospital-based advance care planning programme, Detering et al. [27] demonstrated that 86% of patients allocated to the active advance care planning intervention were willing to discuss their advance care planning wishes.

In the UK, 70% of patients dying from a chronic lung disease die in hospital; similarly, in Australia, 72% of COPD patients die in an acute hospital bed [22, 28]. By contrast, in the ALDS cohort, three-quarters of patients died outside of an acute hospital bed, with half of those patients dying with community palliative care support or in a dedicated palliative care ward or hospice. While this could relate to selection bias, in fact only three patients had written advance care planning directives and only 11 had been referred to palliative care prior to their ALDS referral. Our finding may instead reflect the increased advance care planning activities and improved access to specialist palliative care offered by the integrated service. This finding is also in keeping with Iupati and Ensor [29] who identified that with the introduction of a community hospice programme for COPD, less than one-fifth of patients died in hospital. These findings challenge the idea that dying at home is an unrealistic aim for COPD patients [30], and highlight the importance both of prioritising advance care planning discussions as routine and facilitating access to specialist palliative care, ideally through an integrated shared care model.

New models of integrated care

In a recent review, Maddocks et al. [31] discussed the palliative care needs of patients with COPD, while highlighting the gaps in current care and calling for new models of care that integrate early palliative care into existing services offered by respiratory medicine, primary care and/or rehabilitation teams. The ALDS is a multidisciplinary service in which palliative care principles and practices are embedded into the usual practice of all the team, and as such it represents the model Maddocks et al. [31] called for and provides a solution to address gaps in care. The ALDS respiratory team not only aims to optimise disease management, but also focuses on individualised symptom management (including prescribing and managing morphine for refractory breathlessness), discusses advance care planning and offers “generalist” palliative care [16]. However, having specialist palliative care clinicians also readily available within the ALDS clinic not only supports these practices and the delivery of “generalist” palliative care, it facilitates bidirectional health professional education and greater confidence in managing patients with increasingly complex issues. Similarly, the “normalisation” of palliative care as part of routine best practice care offered by all clinicians, with palliative care clinicians also present in a respiratory clinic for patients with advanced disease, makes palliative care less frightening and more acceptable to patients and their families.

To enable this integrated service approach requires support from palliative care clinicians, and additionally respiratory health professionals need to have some competence in basic palliative care and communications skills, and thus may need to undertake some additional training [15, 16, 32, 33]. This model can then greatly improve the capacity to provide palliative care to a wider range and greater number of respiratory patients, and also facilitates the safe initiation and ongoing management of morphine for refractory breathlessness in patients who need additional treatment beyond nonpharmacological management. Similarly, the involvement of both respiratory medicine and palliative care in such services is essential as patients highly value the input of respiratory medicine teams and continuity of care [3, 17], and it allows for delivery of a comprehensive service, beyond just breathlessness management or disease directed respiratory care.

Integrated respiratory and palliative care is not standard practice nor are such services readily available despite increased interest in new models of care [34–37]. The Breathlessness Support Service in London (UK), the Cambridge Breathlessness Intervention Service (UK) and the Canadian “INSPIRED” programme are new services for patients with advanced lung disease and each has demonstrated improved outcomes [3, 30, 38]. The ALDS shares many similarities with these other services, including a multidisciplinary and multiprofessional single-point-of-access model underpinned by palliative care principles, which offers individualised support to families and patients, and a focus on improving symptom management. Importantly, early and regular communication with other health professionals to provide coordinated care is an essential component of all these models. Our own service, however, is unique in offering long-term shared care and thus ongoing support for primary care health professionals when managing such complex patients. Fundamentally there is not one right model of integrated care; instead, each new service must respond to local needs, while being acceptable to patients and their families, readily accessible, scalable, and sustainable.

Limitations

This was a long-term single-group cohort study, and therefore a causal relationship between ALDS care and outcomes cannot be inferred. As there was no separate control group, a “before and after” comparison was undertaken to investigate any associations between ALDS care and unscheduled healthcare use. This therefore does not allow for temporal confounding particularly related to exacerbations or disease progression. Similarly, the reduction in emergency department presentations identified may have occurred by chance due to the regression to the mean phenomenon. While cohort studies can provide more detailed long-term data than randomised control trials, selection bias in single-group cohorts can also be an issue. Therefore, to rigorously test the effectiveness of the ALDS a cluster multisite randomised study is required, and should include both patient-focused outcomes and health service utilisation.

Conclusions

In this single-group cohort study, integrated respiratory and palliative care was associated with improved end-of-life care. Integrated care services must not only be flexible, accessible and sustainable, but must also consider local health service needs and explore opportunities to form partnerships with primary care. Such models of care require leadership from both respiratory medicine and palliative care clinicians, and also a highly skilled, multidisciplinary and multiprofessional workforce that is willing to and highly proficient in addressing the palliative care needs of patients with advanced nonmalignant respiratory disease.

Disclosures

N. Smallwood 00102-2017_Smallwood (1.2MB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Daniel Steinfort (Dept of Respiratory and Sleep Medicine, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia) for assistance accessing mortality data from the Victorian Births, Marriages and Deaths Register, Kim Yeoh (Dept of Respiratory and Sleep Medicine, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Australia) for helping to collect some of the early data, and Mark Tacey (School of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, Monash University, Clayton, Australia) for assistance with the statistical analysis of the mortality data.

Footnotes

Support statement: Natasha Smallwood receives research funding (as a PhD scholarship) from the Palliative Care Research Network.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside this article at openres.ersjournals.com

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO Definition of Palliative Care www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en Date last accessed: March 31, 2017.

- 2.Erdek MA, Pronovost PJ. Improving assessment and treatment of pain in the critically ill. Int J Qual Health Care 2004; 16: 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higginson IJ, Bausewein C, Reilly CC, et al. . An integrated palliative and respiratory care service for patients with advanced disease and refractory breathlessness: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, et al. . Association between the Medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA 2014; 312: 1888–1896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. . Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2017. http://goldcopd.org/gold-2017-global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd/ Date last accessed: January 31, 2017.

- 7.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. . An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177: 912–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the over 16s: diagnosis and management. Clinical Guideline 101 2010. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101 Date last accessed: June 30, 2017.

- 9.Siouta N, van Beek K, Preston N, et al. . Towards integration of palliative care in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review of European guidelines and pathways. BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang I, Dabscheck E, George J, et al. . The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Version 2.51 2017. www.copdx.org.au Date last accessed: September 30, 2017.

- 11.Rush B, Hertz P, Bond A, et al. . Use of palliative care in patients with end-stage COPD and receiving home oxygen: national trends and barriers to care in the United States. Chest 2017; 151: 41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Palliative Care Services in Australia. Canberra, AIHW, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenwax L, Spilsbury K, McNamara BA, et al. . A retrospective population based cohort study of access to specialist palliative care in the last year of life: who is still missing out a decade on? BMC Palliat Care 2016; 15: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knauft E, Nielsen EL, Engelberg RA, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to end-of-life care communication for patients with COPD. Chest 2005; 127: 2188–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palliative Care Australia. 2010 Workforce for quality care at the end of life position statement 2005. http://palliativecare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/PCA-Workforce-position-statement.pdf Date last accessed: May 31, 2017.

- 16.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care – creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1173–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford GB, Brooksbank MA, Brown M, et al. . Unmet needs of people with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recommendations for change in Australia. Intern Med J 2013; 43: 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philip J, Crawford G, Brand C, et al. . A conceptual model: redesigning how we provide palliative care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Palliat Support Care 2017; 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmadi Z, Bernelid E, Currow DC, et al. . Prescription of opioids for breathlessness in end-stage COPD: a national population-based study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 2651–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, et al. . Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 38: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaspar C, Alfarroba S, Telo L, et al. . End-of-life care in COPD: a survey carried out with Portuguese pulmonologists. Rev Port Pneumol 2014; 20: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philip J, Lowe A, Gold M, et al. . Palliative care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: exploring the landscape. Intern Med J 2012; 42: 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smallwood N, Bartlett C, Taverner J, et al. . Palliation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the end of life. Respirology 2016; 21: Suppl. 2, 143.26610737 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocker GM, Verma JY. ‘INSPIRED’ COPD Outreach Program™: doing the right things right. Clin Invest Med 2014; 37: E311–E319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenwax LK, McNamara BA, Murray K, et al. . Hospital and emergency department use in the last year of life: a baseline for future modifications to end-of-life care. Med J Aust 2011; 194: 570–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smallwood N, Taverner J, Bartlett C, et al. . Palliation of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Eur Respir J 2016; 48: Suppl. 60, 3767. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. . The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National End of Life Care Programme/National End of Life Care Intelligence Network Deaths from respiratory diseases: implications for end of life care in England 2011. www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/resources/publications/deaths_from_respiratory_diseases Date last accessed: April 30, 2017.

- 29.Iupati SP, Ensor BR. Do community hospice programmes reduce hospitalisation rate in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Intern Med J 2016; 46: 295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rocker GM, Cook D. ‘INSPIRED’ approaches to better care for patients with advanced COPD. Clin Invest Med 2013; 36: E114–E120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maddocks M, Lovell N, Booth S, et al. . Palliative care and management of troublesome symptoms for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2017; 390: 988–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palliative Care Australia Primary health care and end of life position statement 2010. http://palliativecare.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/PCA-Primary-Health-Care-and-End-of-Life-Position-Statement.pdf Date last accessed: May 31, 2017.

- 33.Nelson JE, Bassett R, Boss RD, et al. . Models for structuring a clinical initiative to enhance palliative care in the intensive care unit: a report from the IPAL-ICU Project (Improving Palliative Care in the ICU). Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 1765–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booth S, Bausewein C, Rocker G. New models of care for advanced lung disease. Prog Palliat Care 2011; 19: 254–263. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bourke SJ, Peel ET. Integrated Palliative Care of Respiratory Disease. London, Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crawford GB, Price SD. Team working: palliative care as a model of interdisciplinary practice. Med J Aust 2003; 179: 6 Suppl., S32–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simpson AC, Rocker GM. Advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: rethinking models of care. QJM 2008; 101: 697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farquhar MC, Prevost AT, McCrone P, et al. . Is a specialist breathlessness service more effective and cost-effective for patients with advanced cancer and their carers than standard care? Findings of a mixed-method randomised controlled trial. BMC Med 2014; 12: 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

N. Smallwood 00102-2017_Smallwood (1.2MB, pdf)