INTRODUCTION

Malignant melanoma (MM) is the 5th most common cancer in the United States across all ages; however, it ranks third among patients aged 15–39- also known as adolescents and young adults (AYA) (National Cancer Institute, 2015; Weir et al., 2011). There are intrinsic differences in AYA and older melanomas, with AYA having female predominance, increased likelihood of developing superficial spreading melanoma, and presence of somatic BRAF and N-RAS mutations, and germline MC1R mutations (Weir et al., 2011). In contrast, older patients have a male predominance, are more likely to develop lentigo maligna melanoma and develop mutations in NF-1 and kit, and overexpress p53.

Despite its potential importance in elucidating different pathways in melanomagenesis, no comparison of genomic alterations between AYA and older patients exists (Chalmers et al., 2017). Furthermore, melanoma stage is the key prognostic factor in outcomes of melanoma and the relationship between stage and mutational burden and copy number alterations (CNA) has not been well studied. We aim to investigate differences in genomic alterations in melanoma tumors from AYA and older patients and explore the association between genomic characteristics and melanoma staging using publically available datasets.

RESULTS

Across all studies, 94 patients were AYA (TCGA:50; Hodis:32; Krauthammer:5; Gartner:7), while 507 were older (TCGA:311; Hodis:88; Krauthammer:86; Gartner:22) (Table S1). Overall age range was 15–39 in AYA and 40–94 in older patients (Figure S1). Females comprised 50% of AYA and 37.5% of older patients. The extremities were the most commonly affected site in both groups.

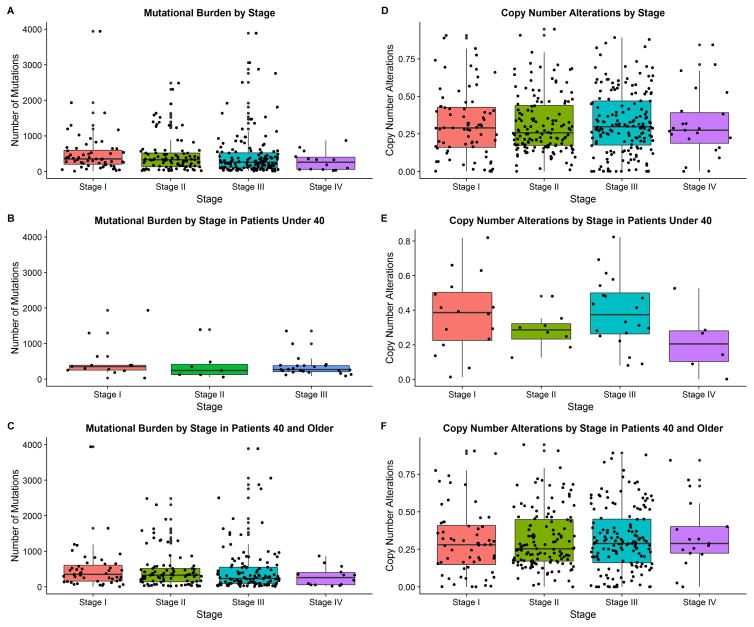

There were no differences in mutational burden between AYA and older patients in the combined studies (p=0.56, Table 1). Interestingly, more advanced stages of melanoma were not correlated with a higher mutational burden across all ages (p=0.75), or in younger (p=0.52) and older (p=0.65) age when analyzed separately (Figure 1a–c).

Table 1.

Gene mutations and copy number alteration characteristics by age group. Data are presented as median and interquartile range for mutational burden, and mean and standard deviation for copy number alterations.

| Characteristic | <40 (n=94) | 40+ (n=507) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutational Burden | |||

| TCGA | 263.5 (185.75–388.75) | 291 (110–555.5) | 0.84 |

| Hodis | 355.5 (188.75–492) | 333 (189–583) | 0.68 |

| Krauthammer | 112 (8–176) | 120.5 (26–287.5) | 0.64 |

| Gartner | 142 (92.5–305) | 163 (115.25–322.25) | 0.5 |

| Overall | 285.5 (143.75–412.75) | 268.5 (104.25–550.25) | 0.56 |

| Copy Number Alterations* | |||

| TCGA | 0.35±0.21 | 0.32±0.21 | 0.3 |

Available in TCGA only

Figure 1.

Distribution of gene mutations and copy number alterations by stage and age group (Staging present in TCGA only) Please note that the stage at diagnosis was utilized for this analysis. However, some of the samples utilized were later metastases collected in these patients.

Figure 1a. Mutational burden by stage at diagnosis

Figure 1b. Mutational burden by stage at diagnosis for patients under 40.

Figure 1c. Mutational burden by stage at diagnosis for patients aged 40 or older.

Figure 1d. Copy number alterations by stage at diagnosis

Figure 1e. Copy number alterations by stage at diagnosis for patients under 40.

Figure 1f. Copy number alterations by stage at diagnosis for patients aged 40 or older

Mutations in AHNAK2 (p=0.01, Table S2) and NF1 (p=0.001) were significantly more likely to occur among older patients, while BRAF mutations were more likely in AYA patients (p<0.001). Mutational burden was higher among RAS (p<0.001) and NF1 (p<0.001) melanoma genetic subtypes, but was lower among the triple wild subtype (p<0.001, Table S3).

Fraction of CNAs did not differ between AYA and older patients (p=0.3). CNAs were not correlated with melanoma stage across all ages (p=0.97), in AYA patients (p=0. 21), and older patients (p=0.9, Figure 1d–f). CNA fraction did not vary among the genetic subtypes of melanoma. Finally, total number of mutations (p=0.74) and mutations due to UV radiation did not differ between the AA and older patients (84.2% vs 86.1%, p=0.09).

DISCUSSION

Normal cellular proliferation is known to result in accumulation of various mutations with age, and melanoma is known as one of the cancers with the highest mutational burden (Martincorena et al., 2015). However, we found that mutational burden of melanoma does not differ between AYA and older patients. Surprisingly, even normal skin carries thousands of mutations, with the key differentiating factor from tumors being a lower number of driver mutations per cell in normal skin (Martincorena et al., 2015). Another study found that invasive melanomas have a higher mutational burden compared to benign lesions, as well as increased presence of CNAs, however they did not examine differences by stage (Shain et al., 2015).

In an effort to classify melanoma based on mutational pattern, TCGA network identified four potential subtypes; the RAS, BRAF, NF1 and triple-wild subtype (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2015). Our finding that BRAF mutations were more likely to occur among AYA patients while NF1 mutations were more likely to be present among older patients are in agreement with this classification indicating that distinct clinical patterns exist.

BRAF is a proto-oncogene which regulates the MAP kinase/ERK signaling pathway (Kim et al., 2015). Mutations in BRAF are well described in MM, but have been identified in benign nevi (Shain et al., 2015). Higher incidence of BRAF mutations among patients <50 has been previously described (Kim et al., 2015).

NF1 is a protein coding gene which acts as a negative regulator in the Ras pathway (Yap et al., 2014). Approximately 14% of melanomas carry mutations in NF1, and recent reports show that NF1 mutated tumors have a higher mutational burden, and occur more often in older patients (Cirenajwis et al., 2017).

Lastly, AHNAK2 is a protein coding gene containing 4300 amino acids not previously identified to have a relationship with melanoma (Han and Kursula, 2014; Shtivelman et al., 1992). It is expressed in all muscular cells and is involved in cytoarchitecture and calcium signaling by interacting with proteins such as S100B (Han and Kursula, 2014).

Each individual study utilizes different sequencing and computational analyses, as demonstrated by different median mutation rates amongst the studies. However, our finding that mutational burden is similar in the AYA and older age groups is found in all studies. Nevertheless, the differences in individual gene mutation rates are not always consistent among studies- as seen with regards to AHNAK2 which is found at a higher mutation rate in older individuals in TCGA and Hodis but not reproduced in Gartner. Given the differences in study technique and multiple comparisons we have performed, this finding may not be reproducible and its significance is uncertain.

A limitation of utilizing the TCGA dataset is that the samples consist of thick primaries, regional, and distant metastatic sites and our findings may not be representative of thinner tumors.

We hypothesize that environmental factors and/or germline genetic host factors likely predispose AYA individuals to develop melanoma at an earlier age. It is postulated that two divergent pathways for development of melanoma exist-one caused by intermittent bursts of sun exposure, while the other is associated with chronic sun exposure (Anderson et al., 2009). Molecular studies found that persons without chronically sun-damaged skin have melanomas with somatic BRAF or N-RAS mutations, and carry germline MC1R variants, while those with significant chronic sun exposure are more likely to have melanomas with somatic mutations in KIT and overexpression of p53 (Anderson et al., 2009).

In conclusion, we found that mutational burden and copy number alterations did not differ between AYA and older patients, nor did these characteristics vary by stage. Future studies should explore factors associated with melanoma development in the AYA population and additional studies sequencing AYA melanoma specifically are needed.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Study Selection

Publically accessible, genomic datasets with mutational burden of MM were identified. Four studies were identified: the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Hodis, Krauthammer and Gartner (Gartner et al., 2013; Hodis et al., 2012; Krauthammer et al., 2012; Tomczak et al., 2015). Each study was accessed and data regarding clinical variables such as age at diagnosis and procurement, gender, race, site of lesion, Breslow depth, ulceration, mitotic rate and stage were extracted. Genomic data were assessed for mutational burden, specifically nonsynonymous genetic mutations, and fraction of CNAs. Melanoma genetic subtypes were defined as: BRAF subtype contains BRAF hot-spot mutations; RAS subtype contains hotspot mutations in N-, K-, and H-RAS; NF1 contains mutations in NF1; triple wild subtype lacks BRAF, RAS and NF1 mutations. Mutations due to UV radiation (C->T change) were assessed from TCGA, Hodis and Gartner (Gartner et al., 2013; Robles-Espinoza et al., 2016). Supplementary materials contain additional methodology.

Statistical Methods

If age at diagnosis was unavailable, age at sample procurement was used. Normally distributed continuous data were analyzed using t-test, otherwise Wilcoxon ranked sum test was used (Figures S2–S3). Categorical data were evaluated using Chi-Square test or Fisher Exact test. ANOVA was used to assess differences in mutational burden or CNAs by stage. An α=0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

RZC is supported by the 5 T32 AR 7569-22 National Institute of Health T32 grant

JA is supported by the Dermatology Foundation Medical Dermatology Career Development Award and the NCI K12 CA076917 Clinical Oncology Research Career Development Program (CORP)

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5 T32 AR 7569-23. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used

- AYA

Adolescent and Young Adult

- CNA

Copy Number Alterations

- MM

Malignant Melanoma

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

Footnotes

The work for this paper was performed in Cleveland, Ohio, United States of America

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson WF, Pfeiffer RM, Tucker MA, Rosenberg PS. Divergent cancer pathways for early-onset and late-onset cutaneous malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2009;115:4176–4185. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Genome Atlas N. Genomic Classification of Cutaneous Melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers ZR, Connelly CF, Fabrizio D, Gay L, Ali SM, Ennis R, et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017;9:34. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirenajwis H, Lauss M, Ekedahl H, Torngren T, Kvist A, Saal LH, et al. NF1-mutated melanoma tumors harbor distinct clinical and biological characteristics. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:438–451. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner JJ, Parker SC, Prickett TD, Dutton-Regester K, Stitzel ML, Lin JC, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies a recurrent functional synonymous mutation in melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13481–13486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304227110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H, Kursula P. Periaxin and AHNAK nucleoprotein 2 form intertwined homodimers through domain swapping. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:14121–14131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.554816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodis E, Watson IR, Kryukov GV, Arold ST, Imielinski M, Theurillat JP, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Kim SN, Hahn HJ, Lee YW, Choe YB, Ahn KJ. Metaanalysis of BRAF mutations and clinicopathologic characteristics in primary melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:1036–1046. e1032. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.02.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauthammer M, Kong Y, Ha BH, Evans P, Bacchiocchi A, McCusker JP, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent somatic RAC1 mutations in melanoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1006–1014. doi: 10.1038/ng.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martincorena I, Roshan A, Gerstung M, Ellis P, Van Loo P, McLaren S, et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science. 2015;348:880–886. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Espinoza CD, Roberts ND, Chen S, Leacy FP, Alexandrov LB, Pornputtapong N, et al. Germline MC1R status influences somatic mutation burden in melanoma. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12064. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shain AH, Yeh I, Kovalyshyn I, Sriharan A, Talevich E, Gagnon A, et al. The Genetic Evolution of Melanoma from Precursor Lesions. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1926–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtivelman E, Cohen FE, Bishop JM. A human gene (AHNAK) encoding an unusually large protein with a 1.2-microns polyionic rod structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5472–5476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak K, Czerwinska P, Wiznerowicz M. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn) 2015;19:A68–77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir HK, Marrett LD, Cokkinides V, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Patel P, Tai E, et al. Melanoma in adolescents and young adults (ages 15–39 years): United States, 1999–2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap YS, McPherson JR, Ong CK, Rozen SG, Teh BT, Lee AS, et al. The NF1 gene revisited - from bench to bedside. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5873–5892. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.