Abstract

Triglyceride (TG) abnormalities are the most prevalent type of dyslipidaemia in the people of northeast China. Many researchers have investigated the prevalence, treatment and control of TG abnormalities, but little is known about the associations between the TG values and the factors that influence TG levels. This study aims to reveal quantile-specific associations of TG with its risk factors. A sample of 16,340 participants in Jilin Province were included in this study. A quantile regression (QR) model was performed to identify the factors that affected TG levels in different quantiles. The distribution of TG levels was different between males and females (χ2 = 155.77, P < 0.001). Body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) were positively associated with TG levels in all quantiles. Drinking was positively associated with TG levels in high quantiles (P70.6 to P95) only in males, while age had a positive association with TG levels in all quantiles only in females. The risk of WC on TG levels was higher with increasing TG levels, and smokers were more at risk for increasing TG levels, as well.

Introduction

Dyslipidaemia is a lipid metabolic disorder that leads to a continuous increase in the plasmatic concentration of cholesterol and triglyceride (TG)1. It is believed to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in most countries2 and is extremely burdensome on the health and economies of countries worldwide3,4. Hypertriglyceridaemia, a condition in which TG levels are elevated, is a common type of dyslipidaemia. In China, based on the Chinese Nutrition and Health Report in 2010, approximately 11.3% of Chinese adults require treatment for TG abnormalities with either lifestyle modification or the administration of medications5–7. Hypertriglyceridaemia is usually asymptomatic until triglycerides are greater than 1000–2000 mg/dl. Thus, although dyslipidaemia is believed to be a risk for coronary artery disease, hypertension and diabetes, it is easy to ignore.

Moderate exercise and drinking have shown to have a positive impact on TG levels8, whereas obesity, smoking, and poor eating habits have negative effects on TG levels9,10. However, TG was often a categorical variable in these studies, so some important information was ignored. On the one hand, continuous TG values can reflect the progression of dyslipidaemia to a certain extent because the occurrence and development of TG abnormalities is a continuous and long-term process. On the other hand, continuous TG values can also contribute to the progression of other diseases. For example, several epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that elevated TG levels were associated with increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk11 and the occurrence and development of pancreatitis, stroke and diabetic microvascular complications12. Therefore, investigating the associations between TG values and influencing factors is of great importance. It is also a challenge to examine the different factors that influence different TG levels rather than examining the factors that influence the mean TG levels.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was one of the most commonly used statistical methods in previous studies; however, OLS cannot fully reflect the whole distribution13 because it focuses on the average. In addition, OLS is not suitable for modelling data with heterogeneous conditional distributions, which would lead to an estimation bias14. Quantile regression (QR)15 is a direct extension of OLS regression, which could analyse the margin effect of each specific quantile condition16, and the least absolute value (WLAV) method was used to estimate parameters17. Further, QR has great flexibility in modelling data with heterogeneous conditional distributions without distributional assumption in the model17,18. Thus, QR models were used to identify the associations between influencing factors and TG (especially the low and high quantiles of TG).

In this study, the associations between the values of TG and the influencing factors were investigated using QR models. Participants were part of the study on the prevalence of chronic diseases and risk factors among adults in Jilin Province, which is located in the central part of northeast China and has a temperate continental monsoon climate19. The QR model was performed to provide a series of coefficients in different quantiles of TG levels to find specific associations between the factors and TG levels.

Results

Descriptive characteristics of participants by gender

As shown in Table 1, the BMI, WC and FBG were significantly higher in males than in females (P < 0.05). The distribution of TG levels was different between males and females (χ2 = 155.77, P < 0.001). The proportions of demographics (occupations, educational level, smoking, drinking, hypertension and diabetes) were significantly different between the two genders (P < 0.05). In addition, there were significant differences between males and females (P < 0.05) in their dietary habits and the mode of transportation.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of participants by gender [ ± SD, n(%)]

| Variables | Total (n = 16340) | Male (n = 7528) | Female (n = 8812) | t/χ2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year)* | 47.40 ± 13.26 | 46.76 ± 13.92 | 47.94 ± 12.65 | −5.71 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 24.12 ± 3.68 | 24.19 ± 3.68 | 24.05 ± 3.68 | 2.26 | 0.024 |

| WC (cm)* | 81.99 ± 10.54 | 84.28 ± 10.43 | 80.03 ± 10.24 | 26.10 | <0.001 |

| Distribution of TG* | 155.77 | <0.001 | |||

| Normal triglyceride | 9828(60.2) | 4206(55.9) | 5622(63.8) | ||

| Borderline high | 2442(14.9) | 1109(14.7) | 1333(15.1) | ||

| Hypertriglyceridaemia | 4070(24.9) | 2213(29.4) | 1857(21.1) | ||

| Residence | 3.43 | 0.064 | |||

| Rural | 8120(50.3) | 3682(48.9) | 4438(50.4) | ||

| Urban | 8220(49.7) | 3846(51.1) | 4374(49.6) | ||

| Occupations* | 476.89 | <0.001 | |||

| Others | 3799(23.2) | 1165(15.5) | 2634(29.9) | ||

| Mental labour | 3064(18.8) | 1506(20.0) | 1558(17.7) | ||

| Manual labour | 9477(58.0) | 4857(64.5) | 4620(52.4) | ||

| Educational level* | 191.44 | <0.001 | |||

| Compulsory | 9753(59.7) | 4061(53.9) | 5692(64.6) | ||

| High school | 4148(25.4) | 2190(29.1) | 1958(22.2) | ||

| Undergraduate | 2439(14.9) | 1277(17.0) | 1162(13.2) | ||

| Smoking* | 3207.61 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 11214(68.6) | 3492(46.4) | 7722(87.6) | ||

| Yes | 5126(31.4) | 4036(53.6) | 1090(12.4) | ||

| Drinking* | 4198.82 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 11243(68.8) | 3267(43.4) | 7976(90.5) | ||

| Yes | 5097(31.2) | 4261(56.6) | 836(9.5) | ||

| Hypertension* | 94.96 | <0.001 | |||

| No | 10568(64.7) | 4572(60.7) | 5996(68.0) | ||

| Yes | 5772(35.3) | 2956(39.3) | 2816(32.0) | ||

| Diabetes* | 5.26 | 0.022 | |||

| No | 14906(91.2) | 6826(90.7) | 8080(91.7) | ||

| Yes | 1434(8.8) | 702(9.3) | 732(8.3) | ||

| Vegetable* | 70.07 | <0.001 | |||

| Occasionally/rarely | 1686(10.3) | 939(12.5) | 747(8.5) | ||

| Often | 14654(89.7) | 6589(87.5) | 8065(91.5) | ||

| Fruit* | 282.80 | <0.001 | |||

| Occasionally/rarely | 7995(48.9) | 4219(56.0) | 3776(42.9) | ||

| Often | 8345(51.1) | 3309(44.0) | 5036(57.1) | ||

| Meat* | 531.75 | <0.001 | |||

| Occasionally/rarely | 10759(65.8) | 4260(56.6) | 6499(73.8) | ||

| Often | 5581(34.2) | 3268(43.4) | 2313(26.2) | ||

| Fish* | 118.06 | <0.001 | |||

| Occasionally/rarely | 14676(89.8) | 6552(87.0) | 8124(92.2) | ||

| Often | 1664(10.2) | 976(13.0) | 688(7.8) | ||

| Eggs/Bean/Bean products* | 38.30 | <0.001 | |||

| Occasionally/rarely | 6514(39.9) | 2808(37.3) | 3706(42.1) | ||

| Often | 9826(60.1) | 4720(62.7) | 5106(57.9) | ||

| Mike/Dairy products* | 10.91 | <0.001 | |||

| Occasionally/rarely | 13869(84.9) | 6465(85.9) | 7404(84.0) | ||

| Often | 2471(15.1) | 1063(14.1) | 1408(16.0) | ||

| Mode of transportation* | 241.70 | <0.001 | |||

| Walking/bicycling | 9005(55.1) | 3656(48.6) | 5349(60.7) | ||

| Driving/riding | 7335(44.9) | 3872(51.4) | 3463(39.3) |

: mean; SD: standard deviations; n: number.

*P < 0.05, “other” included unemployed and retired people

BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; TG: triglyceride.

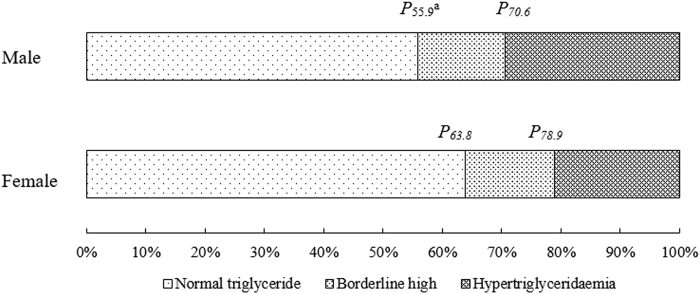

The distribution of TG between males and females

Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1 show the distribution of TG levels along with the corresponding quantiles of the critical values. The differences between males and females were obvious and statistically significant, so the QR model was performed separately by gender afterwards.

Figure 1.

The distribution of TG between males and females (aPx was used to represent the percentile x).

QR model performance

Tables 2 and 3 list the coefficients of multivariate QR between the TG levels and their influencing factors for males and females independently. In males, WC and hypertension were positively associated with TG levels in all quantiles, and the coefficients of WC and hypertension showed an increasing trend with TG levels. BMI was positively association with TG levels in all quantiles and displayed an increasing trend, especially in the middle and high quantiles (P60.5 to P95). Furthermore, smoking status was positively correlated with TG levels compared with non-smokers, and the regression coefficients had a significant increasing tendency in high quantiles (P70.6 to P95). Drinking status and diabetes had similar effects. Compared with people who always walked/biked, those who drove/rode cars had higher risk for increasing TG levels in the middle and high quantiles (P60.5 to P95).

Table 2.

Quantile regression coefficients between TG and variables for males.

| Factors | Normal triglyceride | Borderline high | Hypertriglyceridaemia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P 10.0 | P 25.0 | P 50.0 | P 55.9 | P 60.5 | P 70.6 | P 75.4 | P 95.0 | |||||||||

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Smoking | 0.083 | <0.001 | 0.123 | <0.001 | 0.172 | <0.001 | 0.197 | <0.001 | 0.204 | <0.001 | 0.240 | <0.001 | 0.263 | <0.001 | 0.658 | <0.001 |

| Drinking | −0.023 | 0.140 | 0.044 | 0.008 | 0.126 | <0.001 | 0.151 | <0.001 | 0.178 | <0.001 | 0.168 | <0.001 | 0.255 | <0.001 | 1.083 | <0.001 |

| Mode of transportation | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.067 | <0.001 | 0.099 | <0.001 | 0.115 | <0.001 | 0.122 | <0.001 | 0.123 | <0.001 | 0.122 | 0.003 | 0.380 | 0.009 |

| Diabetes | 0.117 | <0.001 | 0.178 | <0.001 | 0.344 | <0.001 | 0.435 | <0.001 | 0.513 | <0.001 | 0.622 | <0.001 | 0.696 | <0.001 | 3.723 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.069 | <0.001 | 0.089 | <0.001 | 0.127 | <0.001 | 0.134 | <0.001 | 0.151 | <0.001 | 0.210 | <0.001 | 0.235 | <0.001 | 0.495 | 0.002 |

| BMI | 0.021 | <0.001 | 0.031 | <0.001 | 0.046 | <0.001 | 0.057 | <0.001 | 0.060 | <0.001 | 0.081 | <0.001 | 0.095 | <0.001 | 0.155 | <0.001 |

| WC | 0.010 | <0.001 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.027 | <0.001 | 0.028 | <0.001 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.034 | <0.001 | 0.035 | <0.001 | 0.069 | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; Hypertriglyceridaemia: TG ≥ 2.26 mmol/L; Borderline high: TG < 2.26 mmol/L and TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L; Normal triglyceride: TG<1.7 mmol/ L.

Table 3.

Quantile regression coefficients between TG and variables for females.

| Factors | Normal triglyceride | Borderline high | Hypertriglyceridaemia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P 10.0 | P 25.0 | P 60.5 | P 63.8 | P 75.4 | P 78.9 | P 90.0 | P 95.0 | |||||||||

| β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | β | P | |

| Urban | 0.010 | 0.395 | 0.043 | 0.002 | 0.071 | 0.002 | 0.082 | <0.001 | 0.107 | <0.001 | 0.125 | <0.001 | 0.149 | 0.006 | 0.171 | 0.099 |

| Age | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.017 | <0.001 | 0.020 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 0.090 | <0.001 | 0.096 | <0.001 | 0.185 | <0.001 | 0.180 | <0.001 | 0.253 | <0.001 | 0.232 | <0.001 | 0.462 | <0.001 | 0.584 | 0.023 |

| Diabetes | 0.159 | <0.001 | 0.227 | <0.001 | 0.592 | <0.001 | 0.665 | <0.001 | 0.872 | <0.001 | 1.001 | <0.001 | 1.346 | <0.001 | 1.947 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.075 | <0.001 | 0.095 | <0.001 | 0.160 | <0.001 | 0.161 | <0.001 | 0.192 | <0.001 | 0.203 | <0.001 | 0.407 | <0.001 | 0.518 | 0.002 |

| BMI | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.013 | <0.001 | 0.018 | <0.001 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.024 | 0.002 | 0.024 | 0.004 | 0.039 | 0.008 | 0.075 | 0.008 |

| WC | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.022 | <0.001 | 0.028 | <0.001 | 0.030 | <0.001 | 0.041 | <0.001 | 0.045 | <0.001 |

BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; Hypertriglyceridaemia: TG ≥ 2.26 mmol/L; Borderline high: TG<2.26 mmol/L and TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L; Normal triglyceride: TG< 1.7 mmol/ L.

Similarly, WC, smoking, hypertension and diabetes in females had similar effects as those in males (Table 3). BMI also showed a positive association with TG levels in all quantiles and displayed a slightly increasing trend in the low and middle quantiles (P10 to P75.4), and the regression coefficients had a significant increasing tendency in the high quantiles (P78.9 to P95). Age had a positive association with TG levels in all quantiles in females, and females who lived in rural areas were positively associated with increasing TG levels (P10 to P95), compared with those who lived in urban areas.

Discussion

In many studies, TG was treated as a categorical variable, or the mean TG was used. Thus, although influencing factors for TG abnormalities have been extensively explored, little is known about associations between the factors and different levels of TG. In our study, TG was treated as a continuous variable, and the QR model was performed to explore the associations between factors and the progress of TG elevations.

Abdominal obesity has been well established to be linked to dyslipidaemia20. Obesity was believed to decrease the activity of lipolysis through insulin resistance, eventually leading to the failure of TG clearance21,22. In our study, BMI was positively associated with TG in all quantiles. However, the trends in the relationships between the BMI and TG were different in males and females. In males, as TG levels increased, the association was stronger, especially in high quantiles of TG levels (such as P60.5 to P95). By contrast, in females, the trend was different. Although BMI and TG were always positively associated with each other in females, the BMI was strongly and positively associated with TG levels only in high quantiles. This finding suggests that as TG increases to high levels, it is more sensitive to the increase in BMI. This finding indicated that control of one’s BMI should be more emphasized and strengthened among those with high levels of TG in females, while controlling the BMI should always be on the table in males as TG increases. This important information cannot be found in the traditional model when TG was treated as a categorical variable.

Generally, smoking was a risk factor for dyslipidaemia, especially in those with elevated TG levels23,24. In our study, smoking was positively associated with TG levels compared with those who did not smoke. Meanwhile, studies showed that females were at greater risk from smoking than males10. Therefore, smoking cessation is more necessary in females. Furthermore, drinking was shown to be a predictor for higher TG levels in males, with a larger extent of the positive association at a higher quantile. This finding was consistent with the findings in the literature that non-drinkers usually had a lower risk for elevated TG levels9. However, there was no evidence that the intake of alcohol could affect TG levels in females, a feature that may be attributed to fewer female drinkers25. In addition, compared with males who always walk or bike, those who drove or rode cars had a higher risk for TG abnormalities. The association was stronger, especially in the high quantiles of TG levels (such as P60.5 to P95). This finding suggests that, as TG increase to high levels, it will be more sensitive to the mode of transportation. Furthermore, studies have shown that moderate exercise is beneficial for maintaining normal and stable TG levels26. Thus, males with high levels of TG are recommended to change sedentary habits and engage in regular exercise more frequently.

Diabetes is clearly associated with dyslipidaemia27. Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disease with high blood glucose as the main biochemical characteristic, while those with diabetes are more likely already to have had a lipid metabolism disorder. Our results have confirmed this finding. The mechanism may be related to insulin resistance and insulin sensitivity28. Meanwhile, the elevated TG levels could also cause higher free fatty acid levels in the serum, which would lead to a reduction in islet β-cell function29. Similarly, studies have shown that high blood pressure were associated with lipid metabolism disorders, and plasma TG levels were significantly higher than normal30. Patients with hypertension would attain more risk in TG.

Some limitations should be noted. First, the data were derived from a cross-sectional study in Jilin Province, which may limit the generalizability of our results to other regions. Second, health-related behaviours and dietary habits were reported by the participants themselves, which may lead to a reporting bias. Third, some of the variables were not quantified. Thus, more details were neglected, e.g., the amount of the alcohol consumption. Fourth, several potential confounders, such as glucose metabolism and genes, were not under consideration in this study, which may have slightly affected our results.

Conclusion

The risk of WC for TG was positive, and the risk is higher with increasing TG levels. Smokers and those with diabetes or hypertension are at increased risk for TG abnormalities, as well. Males with normal or borderline high TG levels are at high risk for the increase in BMI and alcohol consumption. Meanwhile, the risk of elevated TG is expected to increase with age in females. This finding suggests that middle-aged and elderly females should pay more attention to their TG levels.

Methods

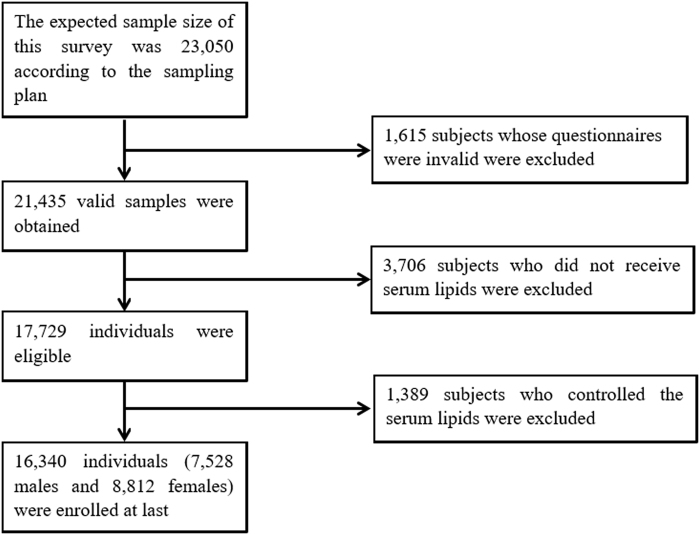

Study population

The data were derived from a cross-sectional study of adult chronic disease, and the risk factors in Jilin Province, China, in 2012 were measured by the School of Public Health, Jilin University, and the Jilin Department of Health. Multistage stratified random cluster sampling was used to select a total of 23,050 participants aged 18–79 years old who had lived in Jilin Province for more than 6 months31 (see details in Part 1 of the Supplementary Material online). This study investigated the association between TG levels and related risk factors. For this purpose, some subjects were excluded due to those who did not get tested (3,706 subjects) or had serum lipid control (1,389 subjects). The ultimate target sample size included a total of 16,340 people in this study (Fig. 2). All of the participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Public Health, Jilin University. All of the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Figure 2.

Study design and participant flow diagram for the present study.

Data Collection and Measurement

To obtain informed consent, all of the participants were interviewed face-to-face by unified and trained investigators. Data, including demographic information (e.g., gender, age, occupation), behavioural factors (e.g., smoking, drinking, physical activity), dietary habits (e.g., vegetables, fruits, meats, eggs), chronic disease prevalence within one year (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) and anthropometric measurements (e.g., height, weight, TG levels) were taken. The participants’ height, weight and waist circumference (WC) were measured using a standardized protocol and process, with participants wearing clothing but no shoes. Blood glucose was monitored using the Bayer Bai Ankang fingertip blood glucose monitor machine (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany) and test paper. Serum lipids were measured using the MODULE P800 biochemical analyser and original auxiliary reagents the morning after participants fasted for more than 10 hours overnight.

Assessment Criteria

Hypertriglyceridaemia was defined as TG ≥ 2.26 mmol/L. Borderline high was defined as TG < 2.26 mmol/L and TG ≥ 1.7 mmol/L. Normal TG was defined as TG < 1.7 mmol/ L32. Hypertension was defined as a resting systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg and/or by the use of antihypertensive medications in the past two weeks33. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as the use of hypoglycaemic agents or a self-reported history of diabetes or fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 7.0 mmol /L34. Smoking was defined as a person who smoked more than daily over the past 30 days. Drinking was defined as a person who consumed an average of more than one alcoholic drink per week, whether the drink was in the form of spirits, beer, wine or other forms of alcohol. Physical labour included production workers, farmers and service workers. Mental labour included office and other technical personnel. Other occupations included students, the unemployed and retirees. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight (kg)/height (m) 2. Dietary habits were classified into two types: “Occasionally/rarely” and “Often”. “Occasionally/rarely” was defined as a person who eats less than three times per week. “Often” was defined as a person who eats three times per week or more. The mode of transportation was divided into two types: “Walking/bicycling” and “Driving/riding”.

Statistical Analysis

The continuous variables were described by using the means ± standard deviations (SD) or the rate and was compared using Student’s t-test. While the categorical variables were described as counts or percentages and were compared using the Rao-Scott Chi-square test. The QR model was used to identify the influencing factors in different quantiles of TG measurements. We defined the candidate variables to be included in the analysis were that could influence the TG levels after referred to a large number of relevant literature and combined the data we have collected and measured. (1) Table 1 lists all of the candidate factors involved in the QR analysis. (2) The multivariate QR analysis was conducted, and (3) the backward stepwise regression was used to select variables. Only the significant variables were retained in the final model and listed in Tables 2 and 3. Statistical analyses were carried out using the R version 3.3.2 (University of Auckland, Oakland, New Zealand). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The survey was implemented by the School of Public Health at Jilin University and the Jilin Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Jilin Province in 2012. Unfortunately, due to relevant regulations, the data cannot be shared.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province, China (grant number: 20180101129JC), the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Science and Technology Department of Jilin Province, China (grant number: 20170520049JH), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 11301213 and 11571068), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number: 2016YFC1303800), and the Scientific Research Foundation of the Health Bureau of Jilin Province, China (grant number: 2011Z116).

Author Contributions

Anning Zhang, Lina Jin and Yan Yao had the original idea for the study, and, with all co-authors, carried out the study design. Lina Jin provided valuable insight into the methodological approach and the organization of the manuscript. Yaqin Yu, Yan Yao and Lina Jin were responsible for the recruitment and follow-up of study participants. Anning Zhang, Li Shen, Yaogai Lv and Jing Dou carried out the statistical analysis and reviewed the consistency in the data that was included in the paper. Anning Zhang wrote the first draft of the manuscript in collaboration with Zhiqiang Xue. Li Shen and Yaogai Lv interpreted the results and wrote the final version of article in collaboration with Yan Yao and Anning Zhang. Xin Guo, Yan Yao and Yaqin Yu revised the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-24230-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yan Yao, Email: yaoyan@jlu.edu.cn.

Lina Jin, Email: jinln@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bayram F, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and associated risk factors in Turkish adults. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 2014;8:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Circulation. 1998;97:596–601. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.97.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao N, et al. Dyslipidemia in rural areas of North China: prevalence, characteristics, and predictive value. Lipids Health Dis. 2016;15:154. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ni WQ, et al. Serum lipids and associated factors of dyslipidemia in the adult population in Shenzhen. Lipids Health Dis. 2015;14:71. doi: 10.1186/s12944-015-0073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li JH, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of dyslipidemia in Chinese adults 2010. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;46:414–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao WH, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of dyslipidemia in people aged 18 years and over in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2005;39:306–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang W, et al. Serum lipids and lipoproteins in Chinese men and women. Circulation. 2012;125:2212–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.065904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou B, et al. The relationship between dietary factors and serum lipids in Chinese urban and rural populations of Beijing and Guangzhou. PRC-USA Cardiovascular and Cardiopulmonary Research Group. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24:528–34. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinton EA. Effects of ethanol intake on lipoproteins and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:346–51. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833c1f41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundtvig M, Hagen TP, Amrud ES, Reikvam A. Reduced life expectancy after an incident hospital diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction–effects of smoking in women and men. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2792–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boullart AC, de Graaf J, Stalenhoef AF. Serum triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:867–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budoff M. Triglycerides and Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins in the Causal Pathway of Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mi B, et al. Association Between Awareness of Hypertension and Health-Related Quality of Life in a Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study in Rural Area of Northwest China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1206. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y, et al. Modeling energy expenditure in children and adolescents using quantile regression. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2013;115:251–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00295.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tighe EL, Schatschneider C. A Quantile Regression Approach to Understanding the Relations Among Morphological Awareness, Vocabulary, and Reading Comprehension in Adult Basic Education Students. J Learn Disabil. 2016;49:424–36. doi: 10.1177/0022219414556771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petscher Y, Logan JA. Quantile regression in the study of developmental sciences. Child Dev. 2014;85:861–81. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gannoun A, Girard S, Guinot C, Saracco J. Reference curves based on non-parametric quantile regression. Stat Med. 2002;21:3119–35. doi: 10.1002/sim.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin CY, Bondell H, Zhang HH, Zou H. Variable Selection for Nonparametric Quantile Regression via Smoothing Spline AN OVA. Stat. 2013;2:255–268. doi: 10.1002/sta4.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang FL, et al. The prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of dyslipidemia in northeast China: a population-based cross-sectional survey. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:61. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0453-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma J, et al. Assessment of triglyceride and cholesterol in overweight people based on multiple linear regression and artificial intelligence model. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16:42. doi: 10.1186/s12944-017-0434-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ugwuja E, Ogbonna N, Nwibo A, Onimawo I. Overweight and Obesity, Lipid Profile and Atherogenic Indices among Civil Servants in Abakaliki, South Eastern Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:13–8. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.109462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth CL, Reinehr T. Roles of gastrointestinal and adipose tissue peptides in childhood obesity and changes after weight loss due to lifestyle intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:131–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zakhar J, Amrock SM, Weitzman M. Passive and Active Tobacco Exposure and Children’s Lipid Profiles. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:982–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huxley RR, Woodward M. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for coronary heart disease in women compared with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Lancet. 2011;378:1297–305. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adeniyi OV, Longo-Mbenza B, Ter Goon D. Female sex, poverty and globalization as determinants of obesity among rural South African type 2 diabetics: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:298. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1622-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szapary PO, Bloedon LT, Foster GD. Physical activity and its effects on lipids. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2003;5:488–92. doi: 10.1007/s11886-003-0112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wysocka-Mincewicz M, Kolodziejczyk H, Wierzbicka E, Szalecki M. Overweight, obesity and lipids abnormalities in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2016;21:70–81. doi: 10.18544/PEDM-21.02.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tangvarasittichai S. Oxidative stress, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2015;6:456–80. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i3.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng S, et al. Clinical characteristics and beta cell function in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus with different levels of serum triglyceride. BMC Endocr Disord. 2015;15:21. doi: 10.1186/s12902-015-0018-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godsland IF, Crook D, Walton C, Wynn V, Oliver MF. Influence of insulin resistance, secretion, and clearance on serum cholesterol, triglycerides, lipoprotein cholesterol, and blood pressure in healthy men. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12:1030–5. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.12.9.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang C, et al. Awareness, treatment, control of diabetes mellitus and the risk factors: survey results from northeast China. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao SP. Key points and comments on the 2016 Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in adults. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2016;44:827–829. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yip GW, et al. Oscillometric 24-h ambulatory blood pressure reference values in Hong Kong Chinese children and adolescents. J Hypertens. 2014;32:606–19. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Permutt MA. Postprandiol hypoglycemia. Diabetes. 1976;25:719–33. doi: 10.2337/diab.25.8.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The survey was implemented by the School of Public Health at Jilin University and the Jilin Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Jilin Province in 2012. Unfortunately, due to relevant regulations, the data cannot be shared.