Highlights

-

•

Patients diagnosed with PNES created sculptures notably different than patients diagnosed with epilepsy.

-

•

Art therapy may help both PNES and Epilepsy patients with emotional expression.

-

•

Along with a conventional diagnostic interview, SAS could help could provide important information at a much quicker rate.

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is the fourth most common neurological condition in the United States, affecting people of all ages, genders, and social status. One in 26 people will be diagnosed with epilepsy within their lifetime [1]. Epilepsy is a disorder of brain function that often manifests as increased, abnormal, electrical activity known as seizures. What is less well known however, is that upwards of 40% of patients assessed for epilepsy will be diagnosed with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) [2]. Most diagnoses of epilepsy are made by video-EEG (V-EEG), which can be long and often futile process, with patients confined to an inpatient unit waiting to have a seizure [3]. If a seizure does not occur during the testing period however, diagnosis is often delayed. Patient of family report symptoms such as blank stares, tremors, spasms or loss of consciousness, but for those with PNES there are no apparent changes in electrical activity within the brain [3], [4]. However, there are difficulties with socialization, cognition, social cognition, quality of life, and other co-morbid psychological issues are common with both epilepsy and PNES [5], [6].

Art therapy is a psychotherapeutic field, in which art therapists engage patients in the creation of art to assist with emotional and physical healing and growth. Art therapists are highly trained professionals who are required to possess a master's degree in art therapy from an accredited institution to practice, as well as complete supervised clinical and internship training https://arttherapy.org/becoming-art-therapist/. As well as uncovering insights or emotions that might be difficult to express verbally, art therapy can offer a safe and nurturing therapeutic environment, in which emotions can be expressed nonverbally. Art therap is offered in a variety of settings including medical, psychiatric, social service, school, and private practices.

The intersection of art and epilepsy has long been recognized, and it has been noted that epilepsy may expand creative or artistic expression [7]. Several famous artists including Vincent Van Gogh, Charles Altamont Doyle, and Giorgio de Chiciro are believed to have suffered from epilepsy. For a highly creative person, visual expression may be a preferred method of communication, and for many it can feel safer and less restrictive than verbalizing emotions [8]. There has been some research that demonstrated that art therapy can be useful in managing the myriad of related psychosocial issues for people with epilepsy, but more is needed [9], [10], [11], [12]. Art therapy is an often underused approach with epilepsy patients, but it may be useful to help patients better manage the comorbid symptoms related to a diagnosis of epilepsy or PNES. The use of a non-verbal approach may assist patients in expressing thoughts and emotions experienced below the conscious level. Art therapy can assist both patient populations in gaining a better understanding of their illness, as well as a tool to increase coping skills [9]. The creation of art may also bring to light differences in the subconscious experience of epilepsy as compared with PNES, similar to those found in conversation analysis [13], [14], [15].

While the purpose of an art therapy session with a patient should remain a primarily therapeutic intervention, the artistic elements and use of materials can and should also be considered. These elements, including line, shape, form, use of space and color not only add detail to the art, but may be a rich source of information about the patient's experience of illness, both consciously and subconsciously [16]. This article details the use of an art therapy assessment with patients on an inpatient monitoring unit. Art therapy assessments rely upon the universality of line, composition, shape, form, texture, and movement within art to identify projective information that may be present in the art work. The following case studies demonstrate an art therapy assessment used to identify differences in the visual expression of seizures for patients with epilepsy and those experiencing PNES.

2. Purpose and rationale

The purpose of this case study was to characterize the similarities and differences in the sculptures created by patients on an inpatient epilepsy monitoring unit (EMU) to represent their experience with seizures, and to presuppose whether underlying psychosocial issues were involved. The seizure assessment sculptures of ten patients who created them while hospitalized on an inpatient EMU between January and November, 2014.

3. Method

A 10″ × 8″ white Styrofoam head devoid of facial features served as the base to the sculpture. A brown mask was later glued to the base to serve as the face. Each patient was also provided with a set of 12 fine point Mr. Sketch™ scented markers in assorted colors, a variety of pipe cleaners, colored construction paper strips, and feathers. A hot glue gun was used to adhere the mask to the head base.

The patient was provided with the mask and markers first, and instructed to divide the mask in half, and on one side depict in an image and/or words how seizures made him or her feel. If the patient did not understand this directive, the art therapist would explain that patients often state feelings of sadness, anxiety, or depression related to their experiences. Once this side was completed, the patient was asked to depict how they believe people who did not know they experience seizures viewed them. Once the mask was completed, it was glued to the supporting head structure. When the mask was firmly set, the feathers and pipe cleaners were given to the patient, and he or she was directed to use these materials on the same side of the head as the emotions to depict how their seizure would appear if it was visible. The patient was encouraged to manipulate the pipe cleaners to mimic how the seizure would move through the brain, as well as to depict thoughts or feelings during an episode. Finally, the patient was asked to use the supplies to complete the other side of the head by adding hair, other adornments, or imagery to represent how they represented their “outer” self.

The patient was then encouraged to write an “artist's statement” about the piece, as well as discuss the sculpture with the therapist. Sculptures were also evaluated for the prominence of color, use of space, amount of materials used, and use of writing or words. Other recurrent themes not included in this scale were charted by the therapist as well. The sculptures were assessed by the art therapy intern who completed the sculpture sessions and reviewed by the art therapy with the internship supervisor. Because the sessions were considered part of regular clinical practice as an expressive task, neither intern nor supervisor was blinded to the diagnosis of the participants. Sessions were documented within the electronic medical record, and this documentation, as well as the photographs and artist statements were included in the chart review. This medical record review was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) with waiver of informed consent as it was determined that there was minimal risk to patients and their protected healthcare information. However, since photos were taken of all the sculptures, and it is our institution's policy to obtain a signed consent for any photography, all patients were given a consent form to sign. Patients who could not read, write, or understand the consent form were excluded from the final review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of participants.

| Age | Gender | Race | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNES group | |||

| 31 | Female | Caucasian | |

| 33 | Male | Caucasian | |

| 23 | Female | African American | |

| 20 | Female | Caucasian | |

| 36 | Female | Caucasian | |

| Epilepsy group | |||

| 23 | Female | Caucasian | |

| 30 | Female | Caucasian | |

| 41 | Female | Caucasian | |

| 35 | Male | Caucasian | |

| 37 | Female | Caucasian | |

4. Case report

Five PNES patients and five epilepsy patient cases were analyzed and compared for similarities and differences in art depiction.

5. Results

The seizure sculpture was initially created as part of an art therapy thesis project to encourage patients to visually express the experience of having a seizure, and help identify any possible psychological stressors related to the diagnosis. After several sessions with patients, a pattern began to appear. It seemed that patients with PNES depicted their seizures and made artistic choices that were markedly different than those of the patients with epilepsy. This was of note, since every sculpture had been made during an individual session with an art therapy intern, so it was unlikely that the representations were influenced by viewing other sculptures by patient's with epilepsy seizure sculptures.

Although distinct themes appeared dependent upon diagnosis, several overlapped (Table 2). Although patients may be diagnosed with both PNES and epilepsy, it should be noted that the patients included in this study had only a diagnosis of PNES or epilepsy, there were none who had both. Both patient groups represented feelings of anxiety, low self-esteem, guilt, lack of independence, and a decreased quality of life. Both groups also expressed considerable issues with stigma and a need for secrecy in regard to their illness, and included imagery of zippers, X's, and the word “shh” around the mouth. This could also represent difficulty with speech during or after a seizure.

Table 2.

Comparison of use of art materials based on diagnosis.

| Epilepsy | PNES |

|---|---|

|

|

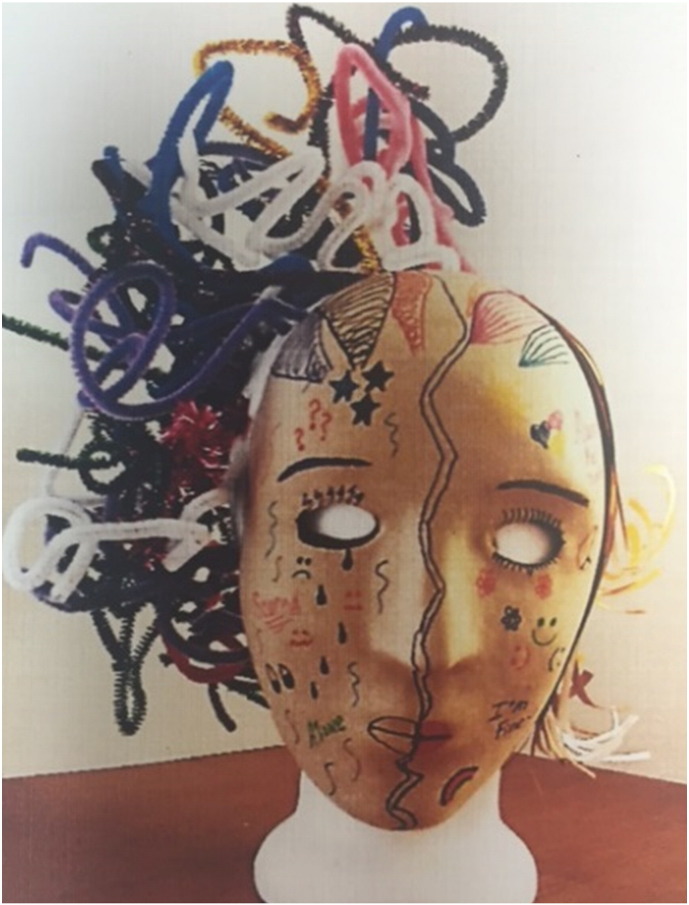

Five distinct themes emerged within the PNES sculptures: 1.) Bold, dark color around at least one eye; 2.) Bold outlining of at least one eye; 3.) Significant use of brown, black, red, yellow, and orange colors throughout the sculpture; 4.) Encapsulation; 5.) Themes of control and strength. Four of the five sculptures included at least one eye outlined in black, as if to emphasize physical trauma in the form of a bruised eye (Fig. 1.) All the patients endorsed issues with PTSD, anxiety, abuse, flashbacks, and depression when discussing the inner feelings portrayed in their sculptures. Other images of suffering included teardrops, wrinkles, angry expressions, and words such as “PTSD” and “depression” included on the side representing their inner feelings. Darker colors such as black and brown were used significantly, as were bold colors of orange, red, and yellow (Fig. 2) in both the depiction of the seizure and related emotions.

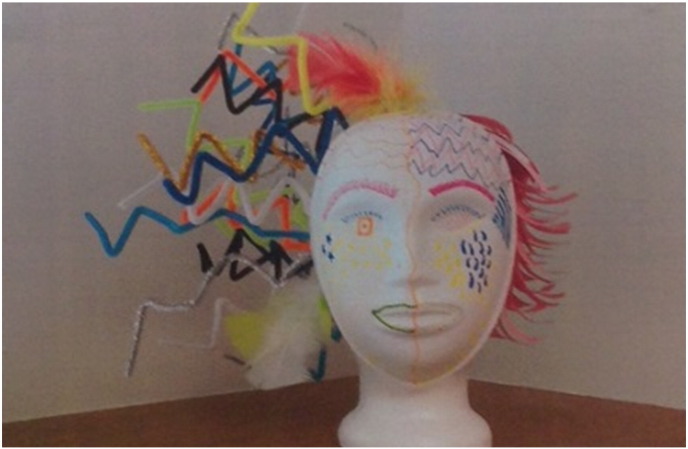

Fig. 1.

Sculpture created by a patient with epilepsy. Note electrical “zig-zag” shapes of pipe cleaners, large variety and use of color, organized use of graphic images such as tear drops. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Sculpture by patient diagnosed with PNES. Note black outline around eye, looping of pipe cleaners, use of drawn symbols and words.

The portrayal of the seizure in the PNES sculptures often included looping or encapsulation of the pipe cleaners, perhaps relating to the inner turmoil felt by the patient. This may also be a representation of the need to disassociate from or repress emotional trauma and the associated feelings. Current understanding of PNES has suggested that the seizure-like episodes are a physical manifestation of this repressed or disassociated emotion [17]. On the side of the face used to show how they presented themselves to the world, many of the patients endorsed a need to hide their feelings and past traumas, and to appear as “normal” as possible. The theme of strength and being/appearing strong to others was prevalent in all processing discussions and within the artist statements, reinforcing the need to hide negative emotions.

Although types and location of epilepsy varied, there were seven themes that emerged in the art of these patients: 1.) Large variety and use of colors; 2.) Electrical imagery (zigzags, lightning bolts); 3.) Exaggerated use of materials, height, and space; 4.) Fluctuating/changing emotions; 5.)Visual representation of ictal (post seizure) stages; 6.) Repetitive use of lines both organized and disorganized; 7.) Themes of resilience, awareness, hope for a cure. Much of this symbolism was consistent with descriptions of epilepsy which often include confusion, feeling foggy or dizzy, the sensation of electricity, and difficulties with emotional regulation.

Color usage was more varied in the epilepsy sculptures, and significantly more materials were used to represent the seizures, often creating a chaotic look. The graphic images drawn on the face however, were more organized and orderly than those seen in the PNES sculptures. Images of electricity were prevalent, with the pipe cleaners used to exaggerate the feeling of electricity (Fig. 1). This type of imagery was similar to a text book description of epilepsy [3]. Patients with temporal lobe epilepsy however, shared similar emotional expression with PNES patients, and used the colors of orange, red, and yellow to represent anger, pain, and difficult memories. This was fitting, as the temporal lobe controls memory, learning, listening, and emotions. While the tendency to excessively or compulsively write has often been noted in patients with epilepsy, the patients with PNES were more likely to include words on the sculpture to describe their emotional state (Fig. 2). The patients with epilepsy used a larger variety of colors however (Fig. 3), and drew graphic elements in a more organized way, as opposed to the scribbled and chaotic drawing and words on the PNES sculptures.

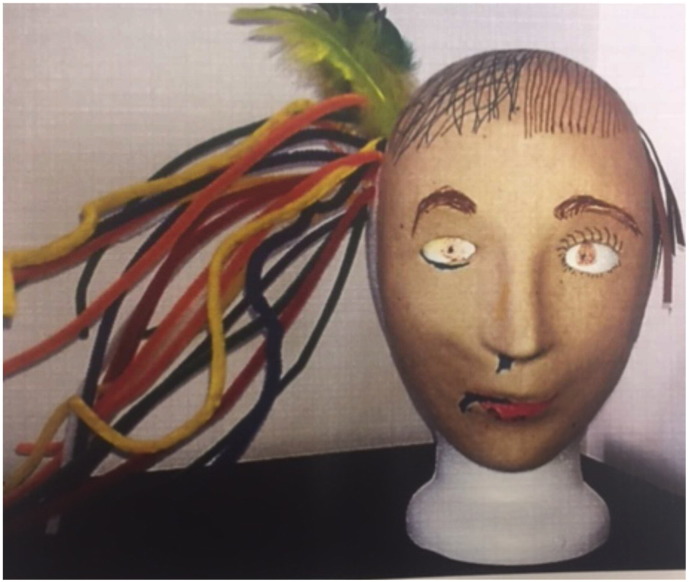

Fig. 3.

Back of sculpture made by a patient with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Note prominent use of materials and color. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

6. Discussion

From these ten cases, it appears there are noteworthy differences in the ways patients with PNES and epilepsy express the effects of their seizures and underlying emotional issues. Notably, there is some similarity in results of the seizure assessment sculpture to the conversation analysis approach. Both approaches garner information about the seizure experience differently than the traditional method of taking a patient history with a focus on “just the facts” [15], [18]. When encouraged to speak descriptively about the seizure experience, PNES patients tended to focus more on the emotional experience of the seizure, while patients with epilepsy described physical sensations. A similar approach was also seen within the seizure sculptures. Patients with PNES were more likely to express issues of depression, anger, and trauma within the art, as well as an inward or encapsulated use of materials. This may be related to an attempt to contain strong emotional feelings and exert control. Patients with epilepsy however, were more likely to depict their seizures as electrical sensations or explosions of energy, with a limited focus on emotional experiences other than frustration at the limitations epilepsy placed upon them, and fear of stigma. Patients with epilepsy would often depict the seizure in a specific spot on the head, and included other physical effects from a seizure involving injury to the nose and tongue, or bitten tongue (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Patient diagnosed with drug-resistant focal epilepsy with focal impaired awareness seizures. Note the depiction of seizures contained in one area of head, and inclusion of physical issues such as secretions such as blood or drool from the nose and lip.

This study had several limitations, and a larger, controlled study is planned for the future. Because participants in the study were inpatient on an epilepsy monitoring unit, many did not initially have a formal diagnosis. Diagnosis for many of the patients was made during their stay, and this information was available to the researchers. Patients included in this case report were diagnosed with either Epilepsy or PNES, but not both. Lack of blinding to diagnosis was an advantage for this case review, since it allowed the intern and supervisor to quickly notice the artistic trends/differences of each diagnosis. Because the seizure sculpture was not initially intended to serve as an assessment in terms of comparison with another diagnosis, the directives were at times broad, and lacking specificity that would have improved the process. In addition, patients may have been unintentionally encouraged to represent their emotions or seizures in a specific way. An assessment scale was created to track the trends noticed in the sculptures, but was used only by the therapist who worked with the patient. Information from this scale was not included in the medical record and therefore not included in this case report.

A future study is planned to address these limitations. Standardized instructions will be used as well to reduce the possible confounding factors. The assessment scale will be expanded and will include a rating of electrical imagery, encapsulation, excessive writing, amount of materials used, and prominence of color. Raters, who will be blind to the diagnosis will individually assess the sculptures. A rating manual and training is under development to ensure all raters are using similar criteria and understand of each item on the scale. The results from the scales will be analyzed for statistical significance and inter-rater reliability.

Conclusions

Just as diagnostic potential has been found in the way people verbally describe the seizure experience, it appears artistic representation of the seizure may also provide valuable insights. Although we are not suggesting SAS as a solitary diagnostic tool, we believe the information gathered through this therapeutic intervention may add a piece of information to of the diagnostic puzzle. Improving the process of differentiating a PNES diagnosis from epilepsy could save much time, money, and frustration for the patient and medical community, since patients may be misdiagnosed for years with traditional video-EEG testing [13]. Additionally the use of art therapy with both types of patients, allowing for both visual and verbal expression, may help address the psychosocial and emotional issues involved as a form of treatment. Although epilepsy is considered a physical malady, it brings with it significant mental health and behavioral issues that are often left unaddressed. Conversely, patients with PNES are often dismissed by neurological services without a clear understanding of how their psychological or traumatic experiences have manifested in seizure-like episodes.

Declaration of interest

Tamara Shella: Conflicts of interest: none.

Sarah Brown: Conflicts of interest: none.

Elia Pestana-Knight: Conflicts of interest: none.

Ethical statement

The authors of the journal article “Development and Use of the Art Therapy Seizure Assessment Sculpture on an Inpatient Epilepsy Monitoring Unit.” Have read, understand, and accept the ethical guidelines for article publication.

Sarah E. Brown, MA, AT, PC

Tamara Shella, MA, ATR-BC

Elia Pestana-Knight, M.D.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epilepsy in adults and access to care - United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 11/16 2012;61(45):909–913. [5 pp.] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drane D.L., LaRoche S.M., Ganesh G.A., Teagarden D., Loring D.W. Clinical research: a standardized diagnostic approach and ongoing feedback improves outcome in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;54:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flower D. Epilepsy part 1: recognizing seizure types and diagnosis. Br J School Nurs. 04 2009;4(3):113–118. [6 pp.] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts N.A., Reuber M. Alterations of consciousness in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: emotion, emotion regulation and dissociation. Epilepsy Behav. 1 2014;30:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amlerova J., Cavanna A.E., Bradac O., Javurkova A., Raudenska J., Marusic P. Emotion recognition and social cognition in temporal lobe epilepsy and the effect of epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav. 7 2014;36:86–89. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovagnoli A.R., Parente A., Villani F., Franceschetti S., Spreafico R. Theory of mind and epilepsy: what clinical implications? Epilepsia. 09 2013;54(9):1639–1646. doi: 10.1111/epi.12255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas R.H., Mullins J.M., Waddington T., Nugent K., Smith P.E.M. Epilepsy: creative sparks. Pract Neurol (BMJ Publ Group) 08 2010;10(4):219. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.217984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gajic G.M. A series of drawings of a patient with schizophrenia-like psychosis associated with epilepsy: captured illustration of multifaced self-expression. Vojnosanit Pregl. 06 2016;73(6):588–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stafstrom C.E., Havlena J., Krezinski A.J. Art therapy focus groups for children and adolescents with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 06 2012;24(2):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stafstrom C.E., Havlena J. Seizure drawings: insight into the self-image of children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:43–56. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anschel D.J., Dolce S., Schwartzman A., Fisher R.S. A blinded pilot study of artwork in a comprehensive epilepsy center population. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;6:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Botha J.R. Introducing a visual art intervention model for stress reduction and the development of coping mechanisms for clients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 04 2010;17(4) (602–602) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papagno C., Montali L., Turner K., Frigerio A., Sirtori M., Zambrelli E. Differentiating PNES from epileptic seizures using conversational analysis. Epilepsy Behav. 8/24/2017 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornaggia C.M., Di Rosa G., Polita M., Magaudda A., Perin C., Beghi M. Conversation analysis in the differentiation of psychogenic nonepileptic and epileptic seizures in pediatric and adolescent settings. Epilepsy Behav. 09 2016;62:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plug L., Sharrack B., Reuber M. Conversation analysis can help to distinguish between epilepsy and non-epileptic seizure disorders: a case comparison. Seizure Eur J Epilepsy. 2009;18:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gantt L. The formal elements art therapy scale: a measurement system for global variables in art. Art therapy. J Am Art Ther Assoc. 01/01 2009;26(3):124–129. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendrickson R., Popescu A., Ghearing G., Bagic A. Thoughts, emotions, and dissociative features differentiate patients with epilepsy from patients with psychogenic nonepileptic spells (PNESs) Epilepsy Behav. 10 2015;51:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins L., Cosgrove J., Chappell P., Kheder A., Sokhi D., Reuber M. Neurologists can identify diagnostic linguistic features during routine seizure clinic interactions: results of a one-day teaching intervention. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]