Abstract

Background

Anatomical and molecular data can be acquired simultaneously through the use of positron emission tomography (PET) in combination with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a hybrid technique. A variety of radiopharmaceuticals can be used to characterize various metabolic processes or to visualize the expression of receptors, enzymes, and other molecular target structures.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search in PubMed, as well as on guidelines from Germany and abroad and on systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Results

Established radiopharmaceuticals for PET, such as 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxyglucose ([18F]FDG), enable the visualization of physiological processes on the molecular level and can provide vital information for clinical decision-making. For example, PET can be used to evaluate pulmonary nodules for malignancy with 95% sensitivity and 82% specificity. It can be used both for initial staging and for the guidance of further treatment. Alongside the PET radiopharmaceuticals that have already been well studied and evaluated, newer ones are increasingly becoming available for the noninvasive phenotyping of tumor diseases, e.g., for analyzing the expression of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), of somatostatin receptors, or of chemokine receptors on tumor cells.

Conclusion

PET is an important component of diagnostic algorithms in oncology. It can help make diagnosis more precise and treatment more individualized. An increasing number of PET radiopharmaceuticals are now expanding the available options for imaging. Many radiopharmaceuticals can be used not only for non-invasive analysis of the expression of therapeutically relevant target structures, but also for the ensuing, target-directed treatment with radionuclides.

Clinical molecular imaging permits the in vivo characterization of biological processes on a cellular and molecular level (1, 2, e1). To this end, molecular imaging in nuclear medicine uses the highly selective binding or metabolization of radioactively labeled molecules to, e.g., visualize the expression of surface receptors or cell metabolism. As part of this, only trace amounts of the substance are injected, meaning that pharmacological effects are unlikely and physiological metabolic processes are not affected.

Methods

Against the backdrop of the authors‘ many years of scientific and specialist clinical experience, this overview is based on a selective literature search in PubMed. The search terms included: “positron emission tomography + PET,” “radiopharmaceutical,” “radiotracer,” “fluorodeoxyglucose + FDG,” “prostate specific membrane antigen + PSMA,” “somatostatin receptor.” Randomized controlled trials in particular were taken into consideration, and current guidelines were also included.

PET in oncology

Positron emission tomography (PET) offers an imaging technique in nuclear medicine imaging that enables the visualization of (often functional) molecular information (3, e1). Today, PET is almost exclusively performed as a hybrid procedure in the context of multimodal imaging, either in combination with computed tomography (PET/CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (PET/MRI) (4). This procedure has become a central component of the diagnostic algorithms used in oncology (table).

Table. Selected clinical indications for positron emission tomography (PET) in oncology.

| Tumor entity | Indication |

Radiophar maceutical |

Featured in guidelines |

Selected publications |

| Lung cancer*1 | Characterization of pulmonary nodules, particularly in patients at high risk for surgery |

18F-FDG | S3 guideline on lung cancer (12) |

((6*3, (13– (15, (e5*3, (6*3) |

| Staging of primary non-small-cell and small-cell lung cancer | ||||

| Recurrence diagnosis in primary non-small-cell and small-cell lung cancer | ||||

| Hodgkin‘s lymphoma*1,*2 |

Prior to treatment initiation, early treatment response; following treatment completion, recurrence diagnosis |

18F-FDG | S3 guideline on Hodgkin‘s lymphoma (e7) |

*3, 16, e8, e9) |

| Head and neck tumors* 1 |

Decision on whether to perform neck dissection | 18F-FDG | S3 guideline on oral cancer (e10) |

(17*3, e11– e13) |

| Laryngeal cancer*1 | Decision on whether to perform laryngoscopic biopsy in suspected persistent disease or recurrence following completion of treatment with curative intent |

18F-FDG | (no German S3 guidelines on laryngeal cancer currently available) |

(e14*3, e11) |

| Esophageal cancer*1 | Detection of distant metastases | 18F-FDG | S3 guideline on esophageal cancer (e15) |

(e16– e18) |

| Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction |

Advanced staging following conventional staging | 18F-FDG | S3 guideline on gastric cancer (e19) |

(e20, e21) |

| Colorectal cancer*1 | Prior to resection of liver metastases with the aim of avoiding unnecessary laparotomy |

18F-FDG | S3 guideline on colorectal cancer (e22) |

(e23*3, e24*3) |

| Cervical cancer | Specific investigations in the setting of recurrence, e.g., prior to salvage surgery |

18F-FDG | S3 guideline on cervical cancer (e25) |

(e26*3, e27) |

| Breast cancer | Diagnosis of metastasis in clinical abnormalities/equivocal findings with other imaging techniques |

18F-FDG | S3 guideline on breast cancer (e28) |

(e29– e31) |

| Malignant ovarian cancer |

Staging and diagnosis of recurrence | 18F-FDG | S3 guideline on malignant ovarian cancer (e32) |

(e33– e35) |

| Melanoma | In suspected or proven stage IIC and III locoregional metastasis | 18F-FDG | S3 guideline on melanoma (e36) |

(e37– e39) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Selection of biopsy area in cases of Richter‘s transformation | 18F-FDG | S3 guideline on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (e40) |

(e41, e42) |

| Prostate cancer | Diagnosis of recurrence following primary treatment |

68Ga/18F -PSMA ligands |

S3 guideline on prostate cancer (27) |

(21, 22, 25, 28) |

| Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors |

Localization, staging, and diagnosis of recurrence |

68Ga- DOTA-TATE/- TOC/-NOC |

ENETS guidelines (33, e43) | (31, 32) |

Possible indications for PET in oncological diseases are shown. Examples of tumor entities have been taken into consideration for which an S3 guideline is available in the oncology guideline program of the German Cancer Society/German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft/Deutsche Krebshilfe), as well as laryngeal cancer and neuroendocrine tumors that are not currently accounted for in this program.

*1 Featured in the guideline on methods of outpatient and inpatient treatment (lung cancer, Hodgkin‘s lymphoma, laryngeal cancer, head and neck tumors) or in specialized outpatient care (esophageal cancer and colorectal cancer)

*2 Not all indications

*3 Randomized controlled clinical trial

Producing radiopharmaceuticals for PET is complex, in addition to which central distribution is limited due to the half-life of the respective nuclides. PET radiopharmaceuticals are primarily labeled with the positron emitters fluorine-18 (18F) or gallium-68 (68 Ga). The positron is the antiparticle of the electron, from which it differs only in terms of the sign of the electric charge and the magnetic moment. If the positively charged positron and negatively charged electron meet in tissue, annihilation occurs, whereby the two particles are converted into two photons of 511 keV each. The angle between the two emission directions is approximately 180° (5). These two photons are ultimately detected in the ring of PET detectors in opposite scintillators and form the basis for the localization of the site of decay in the reconstructed PET image.

By imaging the individual molecular phenotype, PET makes it possible to investigate oncologically relevant questions—such as the differentiation between benign and malignant lesions, initial staging, primary tumor detection, early detection of recurrence, as well as treatment response assessment—quantitatively and, in particular, earlier and more precisely compared with other techniques. The technology behind PET makes the method more sensitive in the detection of even small tumors compared with other imaging methods and, since both molecular information and size are taken into account in lesion characterization, it is able to differentiate these more specifically. A number of radiopharmaceuticals are now available to this end. In particular, early stage diagnosis (e.g., lung cancer [6]) and the assessment of tumor response to treatment (e.g., lymphomas [7]) have been enhanced by this form of metabolic imaging.

A number of radiopharmaceuticals can be labeled either with a diagnostic radionuclide such as gallium-68 or, alternatively, with a suitable therapeutic radionuclide such as the ß-emitter lutetium-177 (177Lu) (8, 9). This offers the possibility to non-invasively analyze expression of the target molecular structure using PET imaging, followed by targeted radionuclide therapy.

This article provides an overview of diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals frequently used in oncological PET investigations, illustrates examples of guideline-compliant clinical applications, and presents a selection of other radiopharmaceuticals.

Radiopharmaceuticals for PET

Glucose metabolism imaging

As a radiopharmaceutical that can be used universally, the glucose analog 2-18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) is the one most frequently used in clinical routine, since it is metabolized by numerous tumor entities as well as other cell types such as, e.g., macrophages. The hallmark of many malignant tumors is increased aerobic glycolysis, in the course of which glucose is metabolized to form adenosine-5‘ triphosphate (ATP). This characteristic property of tumor cells was first described by Otto Warburg in the 1920s (10). As part of this process, glucose is taken up by the insulin-independent glucose transporters 1 and 3 (GLUT1 and GLUT3), which are overexpressed in many tumor cells (11).

The main indications for 18F-FDG PET in oncology include:

Management of invasive diagnostic methods in localized cancer

Differentiation between benign and malignant lesions

Initial staging of malignant tumors

Detection of unknown primary tumors

Detection of recurrence

Early response assessment and therapy surveillance.

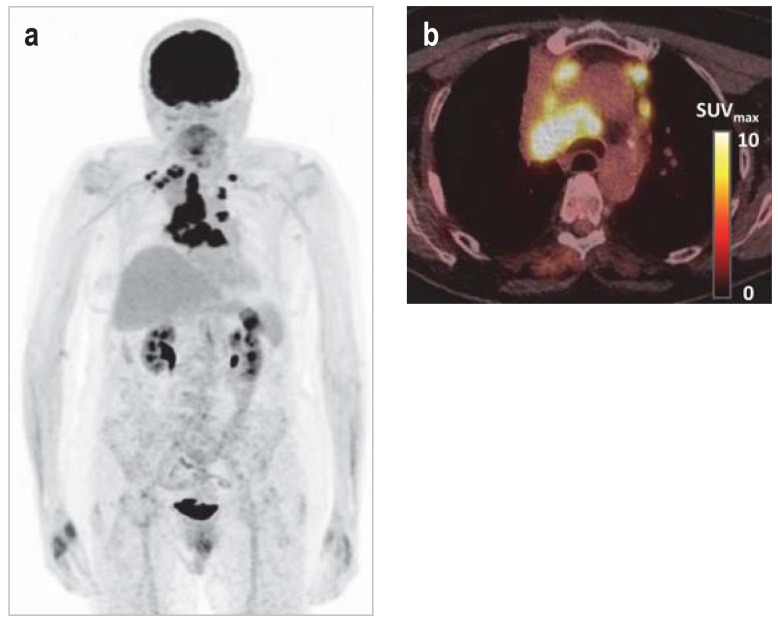

The use of 18F-FDG PET can be illustrated using oncological lung investigations as an example. According to the current S3 guideline, solitary pulmonary nodules measuring >8–10 mm should be investigated using 18F-FDG PET in patients at increased risk for surgery if diagnosis is not possible using invasive diagnostic methods (12). In a meta-analysis, 18F-FDG PET showed a sensitivity of 0.95 and a specificity of 0.82 in the diagnosis of malignant nodules (13). This differentiation between benign and malignant findings makes it possible to avoid further invasive measures and their attendant morbidity and potential mortality. In the case of lung cancer with an indication for curative treatment, 18F-FDG PET should be used for mediastinal and extrathoracic staging, since it currently represents the most sensitive and specific imaging-based staging technique (14). It has high sensitivity in the detection of locoregional and distant metastasis (figure 1), particularly due to the additional detection of metastases unsuspected in previous staging including contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen (15). The use of 18F-FDG PET in lung cancer significantly reduces the rate of futile thoracotomies (e.g., recurrence, distant metastasis, or death within 12 months of surgery); the use of PET in the Dutch randomized controlled PLUS study made it possible to avoid futile thoracotomy in 20% of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (21% compared with 41% of patients in the group that did not undergo PET; relative risk reduction of 51%, p = 0.003) (6).

Figure 1.

Molecular imaging of tumor metabolism

a) 18F-FDG PET of metastatic lung cancer; physiological, intense visualization of the brain, kidneys, and urinary bladder

b) Fusion PET/CT showing multiple lymph node metastases in a right central primary tumor

CT, computed tomography;

18F-FDG, 2–18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose;

PET, positron emission tomography

As a parameter of vitality, 18F-FDG PET has become firmly established in the staging, treatment response assessment, and therapy surveillance of Hodgkin‘s and non-Hodgkin‘s lymphoma (16). For example, the HD15 study conducted by the German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) investigated whether radiotherapy could be restricted to patients with PET-positive residual findings following the completion of chemotherapy. Even without subsequent radiotherapy, patients with PET-negative residual lymphomas had a similar prognosis to patients that achieved complete remission on CT. In that particular study, PET had a negative predictive value (NPV) of 94% and contributed to a de-escalation of chemotherapy (7). 18F-FDG PET is also well-established in the therapy surveillance of solid tumors and, thus, in the individualization of treatment. For example, neck dissection can be dispensed with in patients with locally advanced head and neck tumors in whom a PET yields negative cervical lymph node findings following chemoradiotherapy; this resulted in a 76% reduction in the number of surgical procedures required in the PET surveillance group (54 compared to 221 neck dissections in the group without PET surveillance) (17). The 2-year overall survival rate in the PET surveillance group in the PET-NECK trial was 84.9% compared with 81.5% in the planned neck dissection group (17).

In summary, 18F-FDG represents a radiopharmaceutical that can be used in numerous entities and which, in addition to its use in sensitive initial staging, is increasingly becoming a standard of care in therapy surveillance (table); as such, PET plays a crucial role in personalized medicine.

Prostate-specific membrane antigen imaging

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a transmembrane protein expressed, e.g., in benign and malignant prostate tissue. It functions as an enzyme; however, its actual role in the prostate epithelium is not yet fully understood (18). High PSMA expression is associated with an unfavorable tumor phenotype (higher initial T-stage, higher initial prostate-specific antigen [PSA], and higher Gleason score) and a higher rate of biochemical recurrence (19). The introduction of small-molecule inhibitors—based on a robust PSMA-binding glutamate-urea-lysine scaffold—has been rapidly translated into clinical application due to their excellent imaging properties and high sensitivity in the detection of PSMA-expressing metastases, particularly in prostate cancer (20).

Indications for diagnostic investigations using PSMA ligands include, e.g.:

Diagnosis of biochemical recurrence following primary prostate cancer treatment

Evaluation of PSMA expression prior to radioligand therapy in advanced castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer.

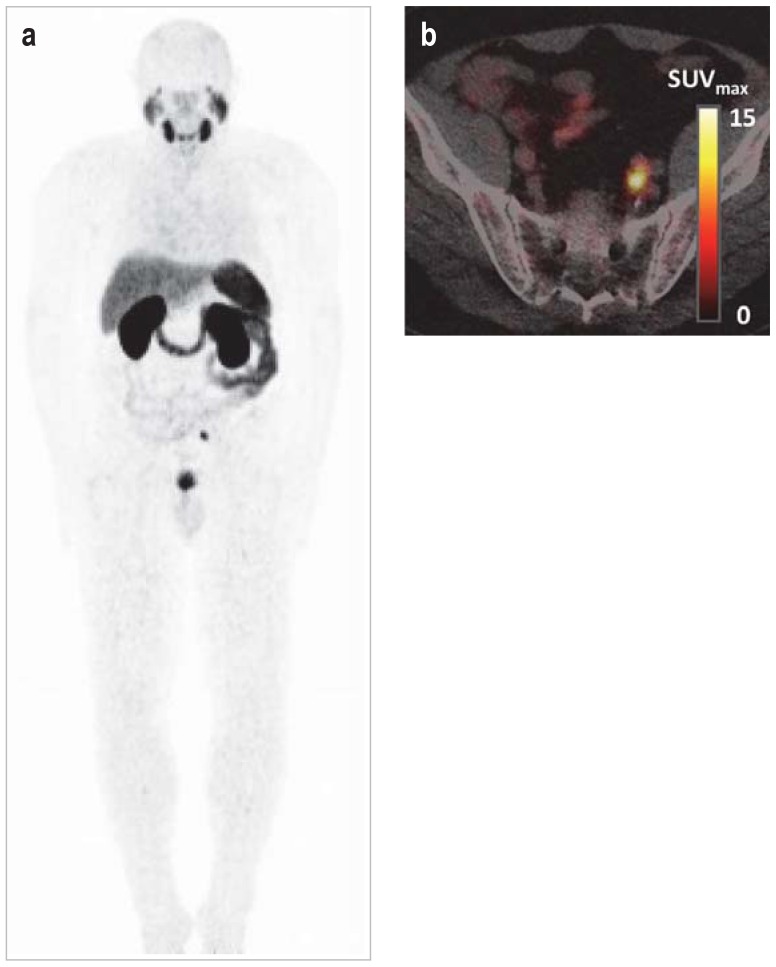

A number of 68Ga- or 18F-labeled PSMA ligands are now available for use in clinical routine (21– 24). In the case of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer, PSMA ligand PET/CT yields high detection rates even in very small metastases or low PSA levels. For example, it was still possible to detect metastases in 39%–46% of cases at PSA levels of = 0.2 ng/ml (21, 22). As such, PSMA imaging (figure 2) is more sensitive than are methods such as bone scintigraphy or CT (25, 26). Therefore, according to the current S3 guideline, PET hybrid imaging with radiolabeled PSMA ligands can be performed in a first step in the context of recurrence diagnosis to assess tumor spread, assuming findings give rise to therapeutic consequences (27). However, the significance of detection of early recurrence is controversial, since these are often asymptomatic biochemical recurrences whose treatment can lead to a reduction in patient quality of life. Simultaneous 68Ga-PSMA ligand PET/MRI appears to be superior to multiparametric MRI for the localization of primary tumors (98% sensitivity compared with 66%) (28). 68Ga-PSMA ligand PET shows higher sensitivity and specificity for the detection of lymph node metastases in the primary staging of high-risk cancer compared with other methods, although metastases from PSMA-negative primary tumors and micrometastases may evade detection (25).

Figure 2.

Molecular imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen

a) 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET in metastatic prostate cancer; physiological, intense visualization of the lacrimal and salivary glands, liver, spleen, small intestine, kidneys, and urinary bladder

b) Fusion PET/CT showing a solitary parailiac lymph node metastasis

CT, Computed tomography;

68Ga, gallium-68;

PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen;

PET, positron emission tomography

A number of PSMA ligands, such as PSMA-617 and PSMA I&T, can also be labeled with ß--emitters, such as 177Lu, which, in early non-randomized observational studies, has opened up the promising option of molecular targeted treatment of advanced castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer that progresses following guideline-compliant systemic therapy (29). Prior diagnostic PSMA ligand PET is helpful to evaluate suitability for PSMA ligand therapy.

Somatostatin receptor imaging

The majority of neuroendocrine tumors (NET) express somatostatin receptors, which can be investigated using molecular imaging. The importance of radiolabeled somatostatin analogs in the diagnosis of NET is established (30), and a number of different ligands are clinically available for PET, e.g., 68Ga-DOTATOC, 68Ga-DOTATATE, and 68Ga-DOTATOC (e2). The ligands bind with varying affinity to the somatostatin receptor subtype 2, as well as in part to other receptors (e2).

The main indications for somatostatin analog PET in oncology include:

Initial localization and staging of endocrine tumors

Detection of unknown primary tumors

Restaging during treatment

Evaluation of somatostatin receptor expression prior to peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PPRT) or somatostatin analog therapy (to estimate probability of response).

A recently published meta-analysis showed a high sensitivity of 90.9% and specificity of 90.6% for 68Ga-DOTATATE PET in the staging of pulmonary and gastrointestinal NET (31). A meta-analysis including 14 studies on 1561 patients showed that, following the use of somatostatin receptor PET, management changed in 44% of cases due to improved staging (32). Thus, somatostatin receptor PET represents an integral part of NET staging in the guidelines of the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) and is, e.g., the method of choice for the localization and staging of pancreatic NET (33).

Radiolabed 177Lu-DOTATATE (34) for targeted radionuclide therapy achieved an estimated progression-free survival of 65.2% after 20 months in the NETTER study on advanced gastroenteropancreatic NET compared with 10.8% under high-dose long-acting octreotide therapy in the control group; the objective response rate was also significantly higher under 177Lu-DOTATATE (18% vs. 3%, p <0.001) (8). Furthermore, the risk of death was 60% lower in the 177Lu-DOTATATE group (hazard ratio of death in the 177Lu-DOTATATE group 0.40, p = 0.004) (8). A number of other tumors, such as meningiomas, pheochromocytomas, and Merkel cell carcinomas, also express high levels of somatostatin receptors and, as such, are amenable to diagnostic investigation and, in some cases, also treatment.

Other radiopharmaceuticals

The use of radiopharmaceuticals, some of which have only recently become available, offers a multitude of other imaging options, particularly in clinical research. Radiopharmaceuticals for the imaging of amino acid transport and metabolism, such as O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (18F-FET) or 11C-methionine, are primarily used in the diagnosis of brain tumors. Radiolabeled amino acids are absorbed to only a small extent in normal brain tissue. Therefore, they can be used in the differential diagnosis of gliomas and non-neoplastic lesions, in biopsy planning for the detection of highly malignant areas, in the definition of tumor extent, and in the assessment of treatment response (e.g., recurrence vs. pseudoprogression, pseudoresponse) (35). Expression of the CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) can be measured using 68Ga-Pentixafor. CXCR4 is physiologically expressed, e.g., on stem and progenitor cells and plays a major role in mobilization and targeted cell migration. However, CXCR4 is also expressed in many hemato-oncological as well as solid neoplasia and is often associated with a tendency to metastasize and an unfavorable prognosis (36). Following 177Lu labeling, targeted endoradiotherapy of CXCR4-expressing cells can be performed (37).

Limitations of PET

Due to its use of radioactive tracers, PET is associated with radiation exposure to the patient; this depends on the activity applied—this being approximately 3.8 mSV (200 MBq 18F-FDG) in the case of 18F-FDG (e3), and lower in the case of somatostatin analogs and PSMA ligands (23)—and thus, if anything, in the lower range of radiation exposure of many diagnostic procedures. Added to this is the fact that, when performing PET/CT, CT causes additional radiation exposure, which is subject to significant variation depending on the scanning protocol used. However, oncological PET is a targeted indication and the benefit to the patient outweighs the theoretical risk of radiation exposure in the applications reported here. Since a definitive diagnosis of malignancy is not possible using non-tumor-selective radiopharmaceuticals such as 18F-FDG—despite their higher specificity compared with other imaging methods—bioptic confirmation is sometimes required to establish therapeutic relevance (e.g., solitary distant metastasis in lung cancer). Furthermore, PET is relatively costly compared to other imaging methods. Given the important role assigned to PET in the guidelines, many oncological indications are reimbursable in the US and most European countries. In Germany, reference is still frequently made in many of these indications to the lack of randomized clinical trials with patient-relevant endpoints. However, this useful standard for the assessment and approval of new therapeutic agents cannot be readily extrapolated to the assessment of diagnostic procedures (38, 39). It is often impossible to translate the value of a diagnostic measure into endpoints such as survival time. For example, although the exclusion of a disease can represent a value that is neutral in terms of survival time, it is nevertheless relevant to the patient, particularly if unnecessary surgery can be avoided as a result. To a certain extent, it is also not (or no longer) possible to randomize diagnostic investigations (e.g., if the procedure already corresponds to the established international standard and/or forms the basis for testing the treatment approach). Were this not the case, linking randomization of the diagnostic procedure with randomization of the subsequent therapeutic options would mean, e.g., also irradiating PET-negative target areas, which is impracticable for ethical reasons. A patient-relevant benefit can also be demonstrated beyond randomized clinical studies, e.g., in comparative accuracy studies or studies simultaneously evaluating a new biomarker and a new therapeutic agent (40, e4).

Key Messages.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is an important component of diagnostic algorithms in oncology.

PET improves diagnostic accuracy particularly in localized disease (e.g., in lung cancer).

PET is able to guide the extent of treatment and helps to individualize therapy.

Numerous radiopharmaceuticals enable—depending on the radionuclide used—both diagnosis and targeted radionuclide tumor therapy.

PSMA ligands and radiolabeled somatostatin analogs expand the oncological armamentarium for targeted tumor therapy.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Christine Schaefer-Tsorpatzidis

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

Prof. Dr. Derlin received travel expenses from ROTOP Pharmaka. He received lecture fees from Janssen-Cilag. He received royalties for publications relating to this subject from the publishers Thieme and Springer.

Prof. Westerholds holds shares in Scintomics. The German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG) provided him with support for studies (third-party funding) relating to this topic.

Prof. Steinbach declares that staff at his institute received study support (third-party funding) from the DFG for the development of PET radiopharmaceuticals.

Prof. Ross received travel expenses and lecture fees from ROTOP Pharmaka.

Prof. Grünwald declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Weissleder R, Mahmood U. Molecular imaging. Radiology. 2001;219:316–333. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma19316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O‘Connor JP, Aboagye EO, Adams JE, et al. Imaging biomarker roadmap for cancer studies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:169–186. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juweid ME, Cheson BD. Positron-emission tomography and assessment of cancer therapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:496–507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spick C, Herrmann K, Czernin J. 18F-FDG PET/CT and PET/MRI perform equally well in cancer: evidence from studies on more than 2,300 patients. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:420–430. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.158808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shukla AK, Kumar U. Positron emission tomography: an overview. J Med Phys. 2006;31:13–21. doi: 10.4103/0971-6203.25665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Tinteren H, Hoekstra OS, Smit EF, et al. Effectiveness of positron emission tomography in preoperative assessment of patients with suspected non-small cell lung cancer: the PLUS multicentre randomized trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1388–1393. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08352-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engert A, Haverkamp H, Kobe C, et al. Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin‘s lymphoma (HD15 trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1791–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, et al. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:125–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatalic KL, Heskamp S, Konijnenberg M, et al. Towards personalized treatment of prostate cancer: PSMA I&T, a promising prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted theranostic agent. Theranostics. 2016;6:849–861. doi: 10.7150/thno.14744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warburg O, Posener K, Negelein E. Über den Stoffwechsel der Tumoren. Biochem Z. 1924;152:319–344. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Geus-Oei LF, van Krieken JH, Aliredjo RP, et al. Biological correlates of FDG uptake in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goeckenjan G, Sitter H, Thomas M, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, therapy, and follow-up of lung cancer Interdisciplinary guideline of the German Respiratory Society and the German Cancer Society—abridged version. Pneumologie. 2011;65:e51–e75. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cronin P, Dwamena BA, Kelly AM, et al. Solitary pulmonary nodules: meta-analytic comparison of cross-sectional imaging modalities for diagnosis of malignancy. Radiology. 2008;246:772–782. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463062148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gould MK, Kuschner WG, Rydzak CE, et al. Test performance of positron emission tomography and computed tomography for mediastinal staging in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:879–892. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200311180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacManus MP, Hicks RJ, Matthews JP, et al. High rate of detection of unsuspected distant metastases by pet in apparent stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: implications for radical radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01477-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehanna H, Wong WL, McConkey CC, et al. PET-CT surveillance versus neck dissection in advanced head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1444–1454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ristau BT, O‘Keefe DS, Bacich DJ. The prostate-specific membrane antigen: lessons and current clinical implications from 20 years of research. Urol Oncol. 2014;32:272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minner S, Wittmer C, Graefen M, et al. High level PSMA expression is associated with early PSA recurrence in surgically treated prostate cancer. Prostate. 2011;71:281–288. doi: 10.1002/pros.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eder M, Schäfer M, Bauder-Wüst U, et al. 68Ga-complex lipophilicity and the targeting property of a urea-based PSMA inhibitor for PET imaging. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:688–697. doi: 10.1021/bc200279b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afshar-Oromieh A, Holland-Letz T, Giesel FL, et al. Diagnostic performance of 68Ga-PSMA-11 (HBED-CC) PET/CT in patients with recurrent prostate cancer: evaluation in 1007 patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1258–1268. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmuck S, Nordlohne S, von Klot CA, et al. Comparison of standard and delayed imaging to improve the detection rate of [68Ga]PSMA I&T PET/CT in patients with biochemical recurrence or prostate-specific antigen persistence after primary therapy for prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:960–968. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3669-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fendler WP, Eiber M, Beheshti M, et al. 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT: joint EANM and SNMMI procedure guideline for prostate cancer imaging: version 10. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:1014–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3670-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dietlein M, Kobe C, Kuhnert G, et al. Comparison of [(18)F]DCFPyL and [(68)Ga]Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC for PSMA-PET imaging in patients with relapsed prostate cancer. Mol Imaging Biol. 2015;17:575–584. doi: 10.1007/s11307-015-0866-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maurer T, Gschwend JE, Rauscher I, et al. Diagnostic Efficacy of (68)Gallium-PSMA positron emission tomography compared to conventional imaging for lymph node staging of 130 consecutive patients with intermediate to high risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2016;195:1436–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pyka T, Okamoto S, Dahlbender M, et al. Comparison of bone scintigraphy and 68Ga-PSMA PET for skeletal staging in prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:2114–2121. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. Interdisziplinäre Leitlinie der Qualität S3 zur Früherkennung, Diagnose und Therapie der verschiedenen Stadien des Prostatakarzinoms. Langversion 4.0, 2016 AWMF Registernummer: 043/022OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Prostatakarzinom.58.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eiber M, Weirich G, Holzapfel K, et al. Simultaneous 68Ga-PSMA HBED-CC PET/MRI improves the Localization of Primary Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol. 2016;70:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahbar K, Ahmadzadehfar H, Kratochwil C, et al. German Multicenter Study Investigating 177Lu-PSMA-617 radioligand therapy in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:85–90. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.183194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oberg K, Modlin IM, De Herder W, et al. Consensus on biomarkers for neuroendocrine tumour disease. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e435–e446. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00186-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deppen SA, Blume J, Bobbey AJ, et al. 68Ga-DOTATATE compared with 111In-DTPA-octreotide and conventional imaging for pulmonary and gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:872–878. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.165803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrio M, Czernin J, Fanti S, et al. The impact of somatostatin receptor-directed PET/CT on the management of patients with neuroendocrine tumor: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:756–761. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.185587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:153–171. doi: 10.1159/000443171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwekkeboom DJ, de Herder WW, Kam BL, et al. Treatment with the radiolabeled somatostatin analog [177Lu-DOTA0,Tyr3]octreotate: toxicity, efficacy, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2124–2130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albert NL, Weller M, Suchorska B, et al. Response assessment in Neuro-Oncology Working Group and European Association for Neuro-Oncology recommendations for the clinical use of PET imaging in gliomas. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18:1199–1208. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Domanska UM, Kruizinga RC, Nagengast WB, et al. A review on CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in oncology: no place to hide. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herrmann K, Schottelius M, Lapa C, et al. First-in-human experience of CXCR4-directed endoradiotherapy with 177Lu- and 90Y-labeled pentixather in advanced-stage multiple myeloma with extensive intra- and extramedullary disease. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:248–251. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.167361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber WA. Is there evidence for evidence-based medical imaging? J Nucl Med. 2011;52(2):74S–76S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.100222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vach W, Høilund-Carlsen PF, Gerke O, et al. Generating evidence for clinical benefit of PET/CT in diagnosing cancer patients. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(2):77S–85S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.085704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vach W, Gerke O. Nutzenbewertung diagnostischer Maßnahmen - quo vadimus? Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2015;58:256–262. doi: 10.1007/s00103-014-2111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Phelps ME. PET: the merging of biology and imaging into molecular imaging. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:661–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Wild D, Bomanji JB, Benkert P, et al. Comparison of 68Ga-DOTANOC and 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT within patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:364–372. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.111724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Boellaard R, Delgado-Bolton R, Oyen WJG, et al. FDG PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour imaging: version 20. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:328–354. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Yang L, Rieves D, Ganley C. Brain amyloid imaging—FDA approval of florbetapir F18 injection. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:885–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1208061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Fischer B, Lassen U, Mortensen J, et al. Preoperative staging of lung cancer with combined PET-CT. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:32–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Maziak DE, Darling GE, Inculet RI, et al. Positron emission tomography in staging early lung cancer: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:221–228. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Hodgkin Lymphoms bei erwachsenen Patienten, Langversion 1.0, 2013, AWMF Registrierungsnummer: 018-029OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E8.El-Galaly TC, d‘Amore F, Mylam KJ, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy has little or no therapeutic consequence for positron emission tomography/computed tomography-staged treatment-naive patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4508–4514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Purz S, Mauz-Körholz C, Körholz D, et al. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for detection of bone marrow involvement in children and adolescents with Hodgkin‘s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3523–3528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie des Mundhöhlenkarzinoms, Langversion 2.0, 2012, AWMF Registernummer: 007/100OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E11.Lonneux M, Hamoir M, Reychler H, et al. Positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose improves staging and patient management in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a multicenter prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1190–1195. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Van den Wyngaert T, Helsen N, Carp L, et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced head-and-neck squamous cell cancer: The ECLYPS Study. J Clin Oncol 2017; J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3458–3464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.5845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Johansen J, Buus S, Loft A, et al. Prospective study of 18FDG-PET in the detection and management of patients with lymph node metastases to the neck from an unknown primary tumor Results from the DAHANCA-13 study. Head Neck. 2008;30:471–478. doi: 10.1002/hed.20734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.de Bree R, van der Putten L, van Tinteren H, et al. Effectiveness of an (18)F-FDG-PET based strategy to optimize the diagnostic trajectory of suspected recurrent laryngeal carcinoma after radiotherapy: the RELAPS multicenter randomized trial. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie der Plattenepithelkarzinome und Adenokarzinome des Ösophagus, Langversion 1.0, 2015. AWMF Registernummer: 021/023OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E16.Flamen P, Lerut A, van Cutsem E, et al. Utility of positron emission tomography for the staging of patients with potentially operable esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3199–3201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.18.3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Wieder HA, Brücher BL, Zimmermann F, et al. Time course of tumor metabolic activity during chemoradiotherapy of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:900–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Monjazeb AM, Riedlinger G, Aklilu M, et al. Outcomes of patients with esophageal cancer staged with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET): can postchemoradiotherapy FDG-PET predict the utility of resection? J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4714–4721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Magenkarzinom, Langversion, 2012, AWMF Registrierungsnummer: 032-009OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E20.Weber WA, Ott K, Becker K, et al. Prediction of response to preoperative chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction by metabolic imaging. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3058–3065. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Ott K, Weber WA, Lordick F, et al. Metabolic imaging predicts response, survival, and recurrence in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4692–4698. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Kolorektales Karzinom, Langversion 1.1, 2014, AWMF Registrierungsnummer: 021-007OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E23.Ruers TJ, Wiering B, van der Sijp JR, et al. Improved selection of patients for hepatic surgery of colorectal liver metastases with (18)F-FDG PET: a randomized study. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:1036–1041. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.063040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Moulton CA, Gu CS, Law CH, et al. Effect of PET before liver resection on surgical management for colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1863–1869. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge der Patientin mit Zervixkarzinom, Langversion, 1.0, 2014, AWMF-Registernummer: 032/033OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E26.Tsai CS, Lai CH, Chang TC, et al. A prospective randomized trial to study the impact of pretreatment FDG-PET for cervical cancer patients with MRI-detected positive pelvic but negative para-aortic lymphadenopathy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Kidd EA, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, et al. Lymph node staging by positron emission tomography in cervical cancer: relationship to prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2108–2113. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms, Konsultationsfassung 0.4.1, 2017, AWMF Registernummer: 032-045OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Mammakarzinom.67.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E29.Hildebrandt MG, Gerke O, Baun C, et al. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) in suspected recurrent breast cancer: a prospective comparative study of dual-time-point FDG-PET/CT, contrast-enhanced CT, and bone scintigraphy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1889–1897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Lin NU, Guo H, Yap JT, et al. Phase II study of lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: clinical outcomes and predictive value of early [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging (TBCRC 003) J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2623–2631. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Schwarz-Dose J, Untch M, Tiling R, et al. Monitoring primary systemic therapy of large and locally advanced breast cancer by using sequential positron emission tomography imaging with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:535–541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge maligner Ovarialtumoren, Langversion 2.0 2016, AWMF-Registernummer: 032/035OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Ovarialkarzinom.61.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E33.Avril N, Sassen S, Schmalfeldt B, et al. Prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy by sequential F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7445–7453. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Hillner BE, Siegel BA, Liu D, et al. Impact of positron emission tomography/computed tomography and positron emission tomography (PET) alone on expected management of patients with cancer: initial results from the National Oncologic PET Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2155–2161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Risum S, Høgdall C, Markova E, et al. Influence of 2-(18F) fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography on recurrent ovarian cancer diagnosis and on selection of patients for secondary cytoreductive surgery. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:600–604. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3cc94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Melanoms, Langversion 2.0, 2016, AWMF Registernummer: 032/024OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Melanom.65.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E37.Mijnhout GS, Hoekstra OS, van Tulder MW, et al. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in melanoma patients. Cancer. 2001;91:1530–1542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Bastiaannet E, Wobbes T, Hoekstra OS, et al. Prospective comparison of [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography in patients with melanoma with palpable lymph node metastases: diagnostic accuracy and impact on treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4774–4780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Reinhardt MJ, Joe AY, Jaeger U, et al. Diagnostic performance of whole body dual modality 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging for N- and M-staging of malignant melanoma: experience with 250 consecutive patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1178–1187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF. Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge für Patienten mit einer chronischen lymphatischen Leukämie, Langversion 0.1, (Konsultationsfassung) 2017, AWMF Registernummer: 018-032OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Chronische-Lymphatische-Leukaemie-CLL.100.0.html (last accessed on 10 October 2017) [Google Scholar]

- E41.Papajík T, Myslivecek M, Urbanová R, et al. 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy- D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography examination in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia may reveal Richter transformation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:314–319. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.802313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Falchi L, Keating MJ, Marom EM, et al. Correlation between FDG/PET, histology, characteristics, and survival in 332 patients with chronic lymphoid leukemia. Blood. 2014;123:2783–2790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-536169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Sundin A, Arnold R, Baudin E, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the standards of care in neuroendocrine tumors: radiological, nuclear medicine & hybrid imaging. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;105:212–244. doi: 10.1159/000471879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]