Abstract

Background

Estrogen receptor-positive (ER-positive) metastatic breast cancer is often intractable due to endocrine therapy resistance. Although ESR1 promoter switching events have been associated with endocrine-therapy resistance, recurrent ESR1 fusion proteins have yet to be identified in advanced breast cancer.

Patients and methods

To identify genomic structural rearrangements (REs) including gene fusions in acquired resistance, we undertook a multimodal sequencing effort in three breast cancer patient cohorts: (i) mate-pair and/or RNAseq in 6 patient-matched primary-metastatic tumors and 51 metastases, (ii) high coverage (>500×) comprehensive genomic profiling of 287–395 cancer-related genes across 9542 solid tumors (5216 from metastatic disease), and (iii) ultra-high coverage (>5000×) genomic profiling of 62 cancer-related genes in 254 ctDNA samples. In addition to traditional gene fusion detection methods (i.e. discordant reads, split reads), ESR1 REs were detected from targeted sequencing data by applying a novel algorithm (copyshift) that identifies major copy number shifts at rearrangement hotspots.

Results

We identify 88 ESR1 REs across 83 unique patients with direct confirmation of 9 ESR1 fusion proteins (including 2 via immunoblot). ESR1 REs are highly enriched in ER-positive, metastatic disease and co-occur with known ESR1 missense alterations, suggestive of polyclonal resistance. Importantly, all fusions result from a breakpoint in or near ESR1 intron 6 and therefore lack an intact ligand binding domain (LBD). In vitro characterization of three fusions reveals ligand-independence and hyperactivity dependent upon the 3′ partner gene. Our lower-bound estimate of ESR1 fusions is at least 1% of metastatic solid breast cancers, the prevalence in ctDNA is at least 10× enriched. We postulate this enrichment may represent secondary resistance to more aggressive endocrine therapies applied to patients with ESR1 LBD missense alterations.

Conclusions

Collectively, these data indicate that N-terminal ESR1 fusions involving exons 6–7 are a recurrent driver of endocrine therapy resistance and are impervious to ER-targeted therapies.

Keywords: breast cancer, endocrine therapy resistance, ESR1 fusion, genomic profiling, structural variation, genomic profiling

Key Message

ESR1 fusion proteins eliminating the LBD are a recurrent mechanism of endocrine therapy resistance in metastatic breast cancer. These fusions are hyperactive and ligand independent. The presence of these fusions contraindicates continued use of ER-targeted therapies. Additional studies are needed to identify appropriate treatment options to overcome this mechanism of resistance.

Introduction

Inhibiting estrogen receptor alpha (ERα/ER/ESR1) activity in estrogen receptor-positive (ER-positive) breast cancer is one of the most successful targeted therapy strategies in cancer. ER-targeted endocrine therapies reduce ligand-mediated ER signaling and can be grouped into two major classes: (i) selective ER modulators/degraders that inhibit estradiol (E2) from binding ER and (ii) aromatase inhibitors that are used in postmenopausal women to reduce E2 production. Both therapy classes disrupt the interaction of estrogen with the ER ligand binding domain (LBD).

Despite the success of these agents, many ER-positive tumors recur and become resistant to endocrine therapy [1, 2]. Although crosstalk with other growth factor pathways, such as HER2, appears to contribute to resistance [3], recent data indicate that acquired ESR1 missense alterations are a common mechanism for resistance, being present in approximately 20–30% of ER-positive recurrent breast cancers [4–7].

Genomic structural rearrangements (REs) produce critical driver alterations in many cancer types [8–10]. In breast cancer, examples of noncoding promoter switching gene fusions have been shown to be recurrent in advanced disease [11, 12], however, only a single example of an ER-alpha protein fusion in a xenograft model (ESR1-YAP1) has been reported [13].

Here, we present a detailed view of RE events in recurrent ER-positive metastatic breast cancer. We identify recurrent ESR1 fusion proteins eliminating the LBD and functionally characterize them as hyperactive and ligand-independent.

Methods

Detailed descriptions of patient samples/methods are presented in supplementary methods, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Normal-primary-metastasis tumor paired tissues from 6 advanced breast cancer patients and 51 unpaired metastatic tumors were obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Health Science Tissue Bank (HSTB) following approval from local Institutional Review Board (IRB# PRO11060660, 11100645, 10050461, and 0506140). Mate-pair sequencing and/or RNAseq was performed to identify REs and fusion transcripts.

Comprehensive genomic profiling was performed on 9542 solid tumor samples and 254 blood samples from breast cancer patients in a CLIA-certified, New York State-, and CAP-accredited laboratory (Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA) [14, 15]. In addition to identification of substitutions, short insertions/deletions, rearrangements, and copy number changes, shifts in copy number (copyshift) at specific rearrangement hotspots were identified to increase sensitivity of rearrangement calls. Briefly, log2 normalized data were compared on each side of previously described RE hotspots. Copyshift-positive was defined as significant differences (P < 0.01 by two-tailed t-test) and an absolute drop in log2 ratio of ≥0.2.

Results

Discovery of ESR1 fusion proteins in recurrent breast cancer

To examine the impact of REs on ER-positive breast cancer progression and therapy resistance, we collected metachronous, patient-matched, primary-recurrent breast cancer tissues from six patients (Pitt-1–Pitt-6), with a median time to recurrence of 7.3 years (supplementary Figure S1 and Tables S1 and S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). In total, 18 tissue samples were available: 4 normal, 4 primary tumor (PrT), and 10 recurrences/metastases from diverse sites including local recurrence (LoR), contralateral breast metastasis (CoM), lymph node (LnM), chest wall (ChM), lung (LuM), liver (LiM), bone (BoM), and brain (BrM).

DNA mate-pair and RNA sequencing were applied to identify REs and fusion transcripts. To assess the biological impact of genomic REs, we focused our analysis on those with both ends overlapping genic regions (bigenic REs) and supporting RNAseq evidence of fusion transcripts (Figure 1A). On average, only 7% of bigenic REs produced fusion transcripts (average: 1.8 expressed bigenic REs per tumor; supplementary Tables S3–S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

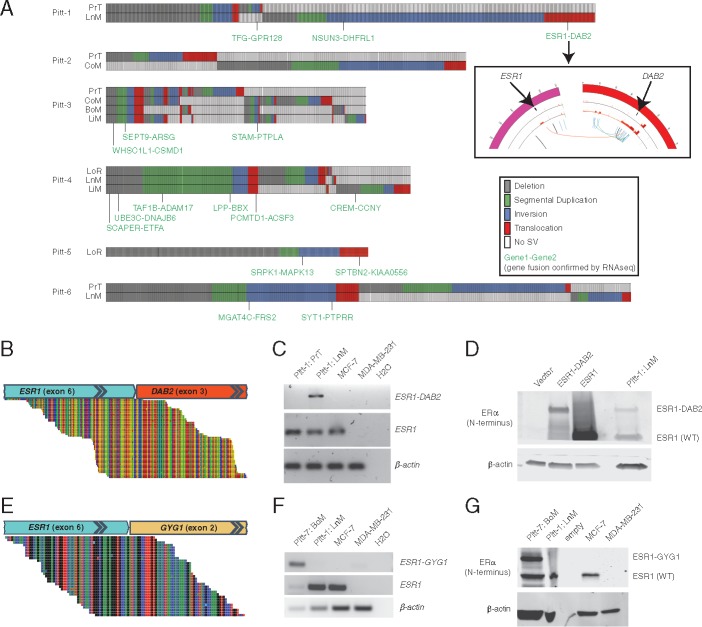

Figure 1.

Rearrangements (REs) in metastatic breast cancer and the identification of ESR1 fusion proteins. (A) Tileplots show the distribution of REs across tumors from Pitt patients 1–6. REs with breakpoints in two genes and supporting RNAseq gene fusion evidence are indicated in green. (inset) Circos plot of copy number variation data for primary (outer ring) and nodal recurrence (inner ring) and structural variants specific to the nodal recurrence (arcs in center). (B, E) RNAseq split read evidence, (C, F) RT-PCR validation, and (D, G) immunoblot of ESR1 fusions in Pitt-1 and Pitt-7, respectively. (D) Overexpression in HEK293 cells was used for positive controls.

This analysis identified a fusion between estrogen receptor-α (ESR1) and disabled-2 (DAB2) in a supraclavicular LnM in Pitt-1 (Figure 1A and B, supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of note, focal copy number amplifications were also seen overlapping with both ends of the translocation only in LnM (Figure 1A inset), a characteristic often seen around REs [16, 17]. The fusion transcript is in-frame and joins ESR1 exons 1–6 with DAB2 exons 3–15. OncoFuse is a naive bayesian classifier built to predict the oncogenic potential of fusion genes [18] and this showed the ESR1–DAB2 fusion to have a score of 0.99 (P < 0.0001). Notably, the location of the fusion junction within ESR1 was identical to the ESR1-YAP1 fusion previously reported in a xenograft model [13]. Expression of the transcript was confirmed to be specific to Pitt-1 LnM by RT-PCR (Figure 1C) and the protein product was confirmed in Pitt-1 LnM by immunoblot (Figure 1D).

RNAseq was then performed on a set of 51 breast cancer metastases. A second in-frame fusion protein (ESR1-GYG1) with an identical ESR1 breakpoint was identified in an ER-positive bone metastasis (Pitt-7) and subsequently validated with RT-PCR and immunoblot (Figure 1E–G). This discovery prompted us to hypothesize that ESR1 fusion proteins with polygamous 3′ partners eliminating the LBD may be a recurrent mechanism of endocrine therapy resistance.

ESR1 fusion proteins are recurrent in ER-positive metastatic breast cancer

To test this hypothesis, we examined hybrid-capture–based target sequencing data from a cohort of 9542 breast tumors and a cohort of 254 ctDNA samples from patients with advanced breast cancer (Foundation Medicine; abbreviated as FMI). It should be emphasized that this approach is not designed to detect ESR1 fusions but is used to provide additional evidence of recurrent ESR1 fusions rather than to assess their prevalence.

Similar ESR1 fusions were identified in four solid tumors (ESR1-SOX9, ESR1-MTHFD1L, ESR1-PLKHG1, and ESR1-TFG) and three ctDNA samples (ESR1-NKAIN2, ESR1-AKAP12, and ESR1-CDK13; Figure 2A). Other nonfusion-producing REs involving ESR1 were identified in 38 additional tumors as follows: intra-ESR1 REs (n = 17), no partner gene/noncoding region (n = 11), incorrect orientation of genes (n = 8), or ESR1-CCDC170 promoter rearrangement [11] (n = 2). These data establish that ESR1 fusions are recurrent in metastatic ER-positive breast cancer, albeit with unique 3′ partners, with junctions clustering between ESR1 exons 6 and 7.

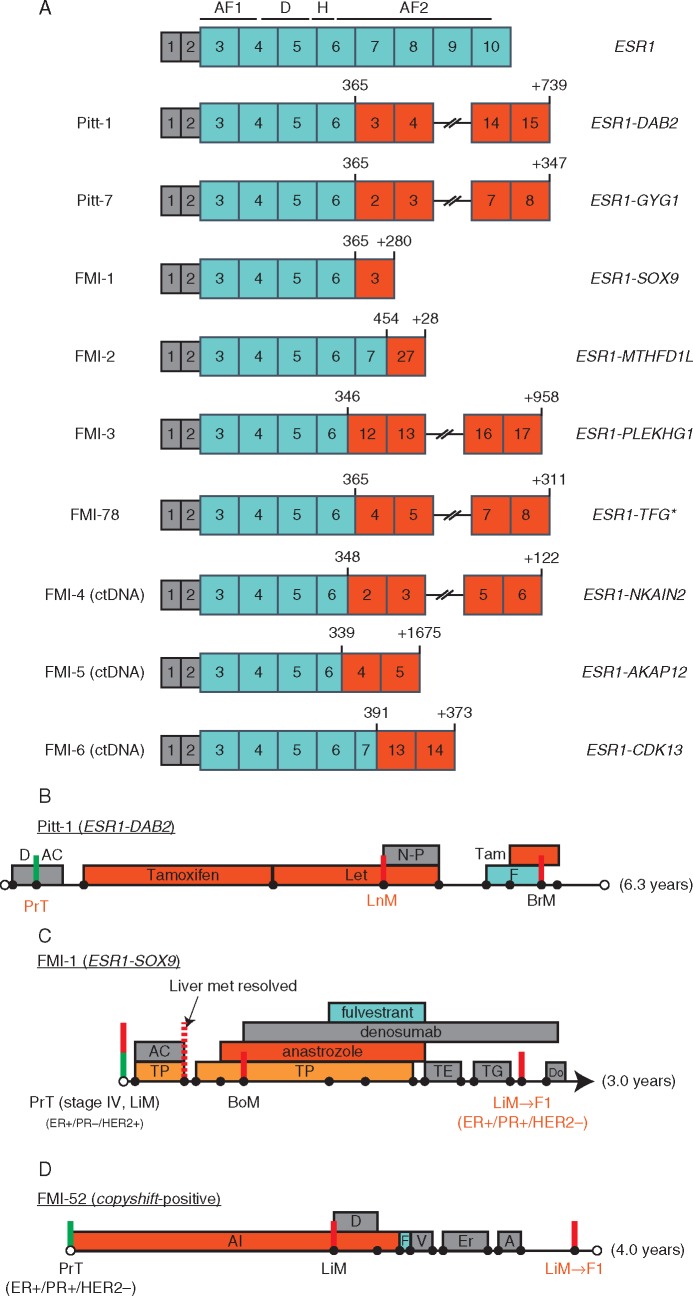

Figure 2.

ESR1 fusion proteins identified via direct discordant read evidence. Gene fusions have clustered junctions in ESR1 between exons 6 and 7. The ESR1 reference transcript is shown at the top with functional domains overlaid. AF1, ligand-independent activation domain; DBD, DNA-binding domain; H, hinge region; AF2, ligand-dependent activation domain. *FMI-78 was called initially as copyshift-positive only, with subsequent RNAseq identified the ESR1-TFG fusion. (B–D) Clinical history summaries for patients with ESR1 fusion positive tumors. Timelines are drawn to scale. Green vertical lines represent the primary tumor surgery while red lines represent major metastatic events (see supplementary Table S9, available at Annals of Oncology online, for more details).

Detailed clinical histories were available for four patients with tumors containing ESR1 fusions (Pitt-1, Pitt-7, FMI-1, and FMI-52; Figure 2B–D; supplementary Table S9, available at Annals of Oncology online). In all cases, the ESR1 fusion was identified in a recurrence following extensive ER-targeted endocrine therapies.

The clinical history of FMI-1 (ESR1-SOX9) is an illustrative case to demonstrate the importance of ESR1 fusions in disease progression (Figure 2C). The patient presented with Stage IV ER-positive, PR-negative, HER2-positive invasive ductal carcinoma with metastatic disease to the liver which was initially treated effectively with HER2- and ER-targeted therapies. However, the liver metastasis biopsy obtained late in disease progression (containing ESR1-SOX9) lost HER2 amplification and become strongly ER/PR-positive. This strongly suggests that the ESR1-SOX9 fusion enabled the ER-positive portion of the tumor to become the dominant clone over the HER2 portion.

FMI-52 presented with a liver metastasis after receiving an aromatase inhibitor for 2 years. Despite switching to fulvestrant and adding various chemotherapy agents, the disease continued to progress. Late in advanced disease, a liver biopsy revealed the presence of the copyshift event likely explaining the resistance to ER-targeted therapies.

ESR1 fusions are ligand-independent and often hyperactive

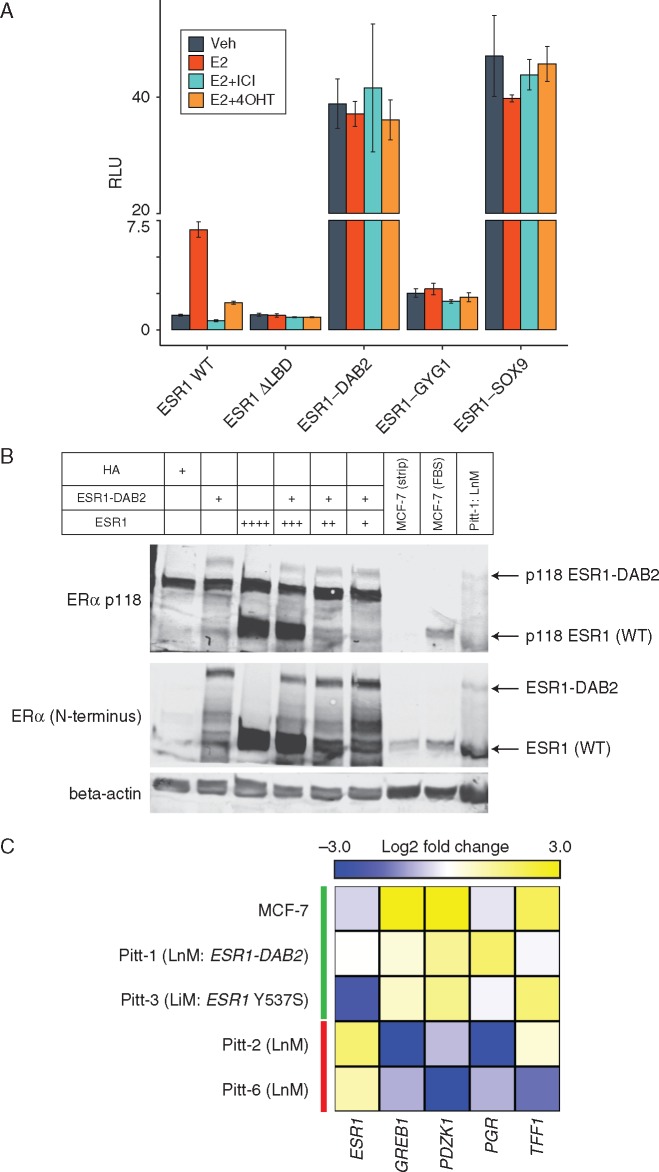

To better understand the functional impact of these fusions of ER signaling, we performed in vitro ERE-Tk-luciferase assays for three ESR1 fusions (ESR1-DAB2, ESR1-GYG1, and ESR1-SOX9; Figure 3A). All three fusions have ligand-independent activity and two (DAB2 and SOX9) are considered hyperactive, resulting in ER activity ∼40× higher than basal wild-type ER activity. The ESR1-GYG1 fusion results in a ∼2–3× increase over basal ER activity but this is ∼20× less than the other two fusions. In contrast, a truncation mutant lacking the LBD (ER ΔLBD) results in a slight decrease compared with basal wild-type ER activity, highlighting a role for the 3′ fusion gene. ESR1-DAB2 is also able to maintain the ligand-dependent pS118 post-translational modification (Figure 3B) and downstream E2 signaling is sustained in Pitt-1 LnM despite the patient receiving aromatase inhibitor therapy (Figure 3C). Together, these data establish that ESR1 fusion proteins are sufficient for endocrine therapy resistance.

Figure 3.

ESR1 fusion proteins are constitutively hyperactive. (A) ESR1 fusion activity determined via ERE-Tk-Luc assay in HEK293 cells. Data points represent mean firefly luciferase values normalized to renilla (transfection control) from three independent transfections in one experiment. Similar results were repeated in three independent experiments. Drug concentrations are as follows: E2 (estradiol: 0.1 nM), 4OHT (4-hydroxy-tamoxifen: 100 nM), ICI (ICI-182, 780: 100 nM). Error bars represent standard deviation. (B) HEK293 cells were transfected with ESR1 and/or ESR1-DAB2. Immunoblot analysis was performed for both the WT and fusion forms of ESR1 and for pS118. Untransfected MCF-7 cells in the absence (i.e. charcoal stripped) and presence of signaling (FBS) were included as a positive control of pS118. (C) Heatmap showing expression of classic estrogen responsive genes in metastatic tumor samples (normalized to paired primary tumor) and MCF-7 (–/+ estrogen as a positive control of E2 signaling) by NanoString analysis.

Development of copyshift method for rearrangement detection

To further explore this exon-targeted, DNA sequencing dataset for evidence of ESR1 fusions, copyshift, a method to detect a shift in copy number within genes, was developed as a surrogate RE call. This method is not intended to have the sensitivity to detect all fusions but is used as an initial screen for further characterization.

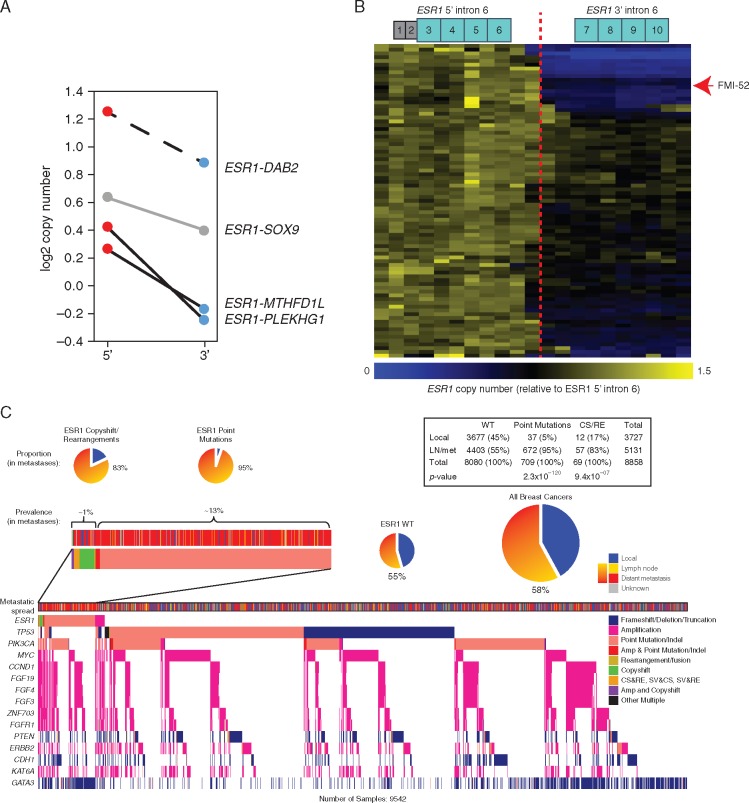

A cohort of 8754 lung adenocarcinomas (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online) was used to benchmark copyshift against ALK rearrangements, whose detection by Foundation Medicine genomic profiling has been validated to >99% sensitivity and specificity [14]. In total, 53/301 ALK rearrangement-positive/copyshift-positive tumors and 6 rearrangement-negative/copyshift-positive tumors were identified. This indicates that copyshift-positive calls are highly likely to be true rearrangement calls (PPV > 89%), whereas copyshift-negative calls do not preclude the possibility of an RE due to copy-neutral rearrangements and the ultra-conservative nature of the method (FNR = 85%). Additionally, ESR1 copyshift-positive tumors are extremely rare (<0.01%) in lung adenocarcinomas (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online), indicating that copyshift events follow the expected disease distribution patterns of their corresponding fusions. Importantly, 2/3 ESR1 fusions detected in the solid tumors evaluated by Foundation Medicine using discordant read mapping, plus the ESR1-DAB2 fusion in Pitt-1 LnM, were copyshift-positive (Figure 4A). Copyshift-positivity was directly confirmed in one case (FMI-78) that was subsequently profiled via RNAseq and resulted in the identification of a previously unidentified ESR1-TFG fusion. Thus, copyshift can be used to detect rearrangements likely to lead to fusions with high specificity, but lower sensitivity.

Figure 4.

Recurrent ESR1 copyshift at exon 6 is enriched in ER-positive metastatic breast cancer. (A) Samples containing ESR1 fusion proteins are often positive for copyshift. Adapting the method to mate pair sequencing data also showed ESR1-DAB2 is copyshift-positive (dashed line). (B) Heatmap showing the shift in copy number across ESR1. Of the 9542 breast cancer genomic profiles examined, the 83 copyshift positive are shown. FMI-52 is highlighted with the red arrowhead. (C) Tileplot illustrates the genomic context of ESR1 fusions and copyshift positivity. ESR1 alteration containing samples (point mutations, fusions, copyshift) are found predominantly in metastatic disease.

Copyshift reveals recurrent ESR1 rearrangements in endocrine therapy-resistant ER-positive metastatic breast cancer

Application of copyshift to all 9542 breast cancer samples identified 83 tumors likely to contain a rearrangement in ESR1 (Figure 4B, supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online). The vast majority of these samples were ER-positive (35/41 with available clinical ER IHC data; P < 0.001, by chi-square). Copyshift-positive samples are also highly enriched in metastatic disease (odds ratio = 3.59, P < 0.001 by chi-square). Co-mutation analysis revealed that copyshift-positive samples significantly co-occur with missense alterations in ESR1 (odds ratio = 4.94, P < 10−8). This suggests polyclonal endocrine therapy resistance similar to that previously reported for ESR1 missense alterations [7, 19]. In support of this, all three ctDNA samples with ESR1 fusion proteins contain ESR1 missense alterations, with two containing three separate mutations in trans. Other genes with significantly co-occurring alterations with copyshift-positivity include: ZNF703, GNAS, GLI1, FGFR1, VHL, and CCND1 (supplementary Table S8, available at Annals of Oncology online), some of which have been previously implicated in endocrine therapy resistance [12, 20].

Discussion

Our data establish ESR1 fusion proteins as recurrent, albeit rare, events, enriched in metastatic ER-positive breast cancer and likely contribute to endocrine therapy resistance. We identify nine novel ESR1 fusion proteins, all with junctions between ESR1 exon 6 and 7 and direct evidence from DNA and/or RNA sequencing. The diverse 3′ fusion partner genes and wide range of contributed amino acids (range: 28–1675) suggest that many possible 3′ partners can produce ligand-independent ESR1 fusions. These results establish that ligand independence can be established with minimal novel function from the 3′ fusion partner but the overall activity is ultimately dependent on the characteristics of each fusion.

Further, identification of shifts in copy number at or near exon 6 identified 83 tumors from 80 patients likely to contain an RE in this region, including 2 tumors with both direct (read-level) and indirect (copyshift) lines of evidence and another tumor with indirect evidence (copyshift) and direct confirmation of an ESR1 fusion transcript via RNAseq. The clustering of these events around ESR1 exon 6, the strong enrichment in ER-positive metastatic disease, and functional data supporting ligand-independent activation indicate that ESR1 fusion proteins drive resistance to ER-targeted therapies in a subset of patients with advanced breast cancer.

The use of multiple methods employed to detect these ESR1 RE events imparts varying levels of confidence on the likelihood that each result in a functional fusion protein product. This is important to keep in mind as many predicted rearrangement events are not expressed or translated. For example, ESR1-DAB2 was detected in tumor-derived DNA, RNA, and protein proving that this DNA RE produces an in-frame gene fusion and a translated protein product. In vitro functional studies further establish this fusion is constitutively hyperactive. ESR1-GYG1 was detected in tumor-derived RNA and protein, establishing that this fusion transcript is expressed, in-frame, and produces a stable protein product. ESR1-SOX9, ESR1-MTHFD1L, ESR1-PLEKHG1, ESR1-NKAIN2, ESR1-AKAP12, and ESR1-CDK13 were all detected with high confidence and base-pair level resolution only via DNA sequencing. Thus, it is possible these events do not lead to a fusion transcript despite the strong sequencing evidence and clustering of fusion junctions to ESR1 exons 6–7. Finally, the 81 copyshift-only events, for which there is only evidence of an RE with no direct evidence of a gene fusion, are the least confident for the identification of fusion products. However, the enrichment of ESR1 copyshift calls in breast cancer (∼10× enrichment in breast cancer over lung adenocarcinoma) indicates that these events are linked to the biology of this disease and benchmarking of copyshift on ALK REs in lung adenocarcinoma demonstrates the conservative nature of copyshift-positive calls. Further, within breast cancer, these events are strongly enriched in ER-positive metastatic disease and co-occur with ESR1 missense alterations. The clinical history available for these patients also strongly supports their role in endocrine therapy resistance.

Our detection of copy number shifts within ESR1 complements similar findings describing ‘truncating amplifications’ in endometrial cancer [21]. Of note, Holst et al. link one truncating amplification to a gene fusion. Although we did directly detect (via discordant read analysis) seven truncating REs that delete a portion of the LBD (defined as exons 7–10; see supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online), none were copyshift-positive or were considered fusion candidates. Although not examined here, the frequency of ESR1 truncating events and their potential role in endocrine therapy resistance warrants further study.

The majority of ESR1 fusions were identified using a DNA sequencing strategy not explicitly designed to detect these events, making it difficult to establish the true frequency with which they occur. Copyshift provides some power to detect additional REs, although benchmarking suggests that it detects only about one-third of REs. Since the estimated false-negative rate is much higher than the estimated false positive rate (FNR = 85%, FPR < 0.1%), we consider our detection rate of ESR1 fusion events of ∼1% of metastatic breast cancer to represent a lower-limit. These data strongly advocate for additional studies in recurrent ER-positive breast cancer to refine this estimate.

Although ESR1 fusions appear to be relatively rare, we speculate that they may be increasing in frequency. We postulate that as more aggressive ER-targeted endocrine therapies are employed for patients with ESR1 LBD missense tumors, ESR1 fusions will represent a mechanism of secondary resistance. This is supported by the following observations. First, ESR1 fusions detected with direct read-level evidence are more frequent in metastatic patients tested via a recently launched ctDNA assay (3/254; 1.2%) compared with metastatic solid tumors profiled over the previous 4–5 years (3/5131; 0.058%). Second, ESR1 missense alterations are the most common co-occurring alterations in ESR1 fusion or copyshift-positive samples. In fact, each of the three fusions identified via the ctDNA assay contained at least one known ESR1 LBD mutation and two contained three LBD mutations in trans. Third, many of the patients with ESR1 fusion-positive tumors received multiple lines of endocrine therapy, including relatively aggressive options like GnRH agonists, fulvestrant, and multiple lines of aromatase inhibitor therapies. Conclusive evidence needs to establish that ESR1 fusions can represent secondary resistance mechanisms to second and third line endocrine therapies, and remains to be gathered.

The clinical implications of ESR1 fusions are profound. The in vitro evidence demonstrating constitutive, ligand-independent activity combined with the lack of the LBD suggest that the presence of an ESR1 fusion is a contraindication for continued ER-targeted endocrine therapies. This may help to redirect clinical decisions to potentially more efficacious therapies. It also highlights the dependency of our current endocrine therapies on the ER LBD. The development of therapies targeting the N-terminus of ER or other downstream signalling molecules, such as CDK4/6, are therapeutic strategies to be explored for ESR1 fusion-positive tumors. More broadly, this study highlights the importance of REs as a class of genomic alterations in advanced breast cancer and demonstrates a contribution to therapy resistance through the generation of ESR1 fusion proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Boone and M. Sikora for critical discussions and reading of the manuscript. We thank D. Peters, A. Rajkovic, P. Shaw, and K. Bruce for access to sequencing equipment, F. Han for performing immunoblots, and C. Andersen for providing the Nanostring codeset. The authors acknowledge support from the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, UPMC, and by the University of Pittsburgh Center for Simulation and Modeling through the high-performance computing resources provided. The authors acknowledge support of the Health Sciences Tissue Bank and the rapid autopsy team especially Christina Kline, Lindsay Mock, Michelle Bisceglia, Louise Mazur, Sue Kelly, Rajiv Dhir, Ron Johnson, and many other clinicians and staff, as well as patients at UPMC for making the study possible. Sequence data from Pitt samples will be made available upon request and under regulatory compliance. Samples from Foundation Medicine are part of routine clinical testing and raw data are not available for public release.

Funding

The study was funded in part by a CDMRP Breast Cancer Postdoctoral Fellowship to RJH (W81XWH-11-1-0582), the Fashion Footwear of New York (FFANY), and Breast Cancer Research Fund (AVL, SO, BP, and NED). This project used UPMC Hillman Cancer Center Cancer Genomics and Tissue and Research Pathology Services, supported by award P30CA047904 from NIH, utilized sequencing services performed in the Genomics Research Core at the University of Pittsburgh, and utilized common equipment supported by NIH UL1-RR024153 and UL1-TR000005 grants to the University of Pittsburgh’s Clinical & Translational Science Institute. AVL is a recipient of a Scientific Advisory Council award SAC150021 from Susan G. Komen for the Cure and is a Hillman Foundation Fellow. NP was supported by a training grant from the NIH/NIGMS (2T32GM008424-21) and an individual fellowship from the NIH/NCI (5F30CA203095). AN was supported by a training grant from NIH (T32GM008424). BP was supported from Susan G. Komen for the Cure and the Commonwealth Foundation.

Disclosure

RJH, SET, JHC, CAP, PVB, SM, MR, LMG, MEG, JS, SMA, JR, GMF, PJS, and JC receive salary and have ownership interest (including patents) in Foundation Medicine. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2005; 365(9472): 1687–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strasser-Weippl K, Goss PE.. Advances in adjuvant hormonal therapy for postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23(8): 1751–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Osborne CK, Schiff R.. Mechanisms of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Annu Rev Med 2011; 62(1): 233–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toy W, Shen Y, Won H. et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet 2013; 45(12): 1439–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jeselsohn R, Yelensky R, Buchwalter G. et al. Emergence of constitutively active estrogen receptor-α mutations in pretreated advanced estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20(7): 1757–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robinson DR, Wu Y-M, Vats P. et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet 2013; 45(12): 1446–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang P, Bahreini A, Gyanchandani R. et al. Sensitive detection of mono- and polyclonal ESR1 mutations in primary tumors, metastatic lesions and cell free DNA of breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 22(5): 1130–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S. et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science 2005; 310(5748): 644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi YL, Soda M, Yamashita Y. et al. EML4-ALK mutations in lung cancer that confer resistance to ALK inhibitors. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(18): 1734–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hartmaier RJ, Albacker L, Chmielecki J. et al. High-throughput genomic profiling of adult solid tumors reveals novel insights into cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Res 2017; 77(9): 2464–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Veeraraghavan J, Tan Y, Cao X-X. et al. Recurrent ESR1-CCDC170 rearrangements in an aggressive subset of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancers. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giltnane JM, Hutchinson KE, Stricker TP. et al. Genomic profiling of ER + breast cancers after short-term estrogen suppression reveals alterations associated with endocrine resistance. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9(402): eaai7993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li S, Shen D, Shao J. et al. Endocrine-therapy-resistant ESR1 variants revealed by genomic characterization of breast-cancer-derived xenografts. Cell Rep 2013; 4(6): 1116–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA. et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31(11): 1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chung JH, Pavlick D, Hartmaier R. et al. Hybrid capture-based genomic profiling of circulating tumor DNA from patients with estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(11): 2866–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stephens PJ, Greenman CD, Fu B. et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell 2011; 144(1): 27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stephens P, McBride D, Lin M-L. et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature 2009; 462(7276): 1005–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shugay M, Ortiz de Mendíbil I, Vizmanos JL, Novo FJ.. Oncofuse: a computational framework for the prediction of the oncogenic potential of gene fusions. Bioinformatics 2013; 29(20): 2539–2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schiavon G, Hrebien S, Garcia-Murillas I. et al. Analysis of ESR1 mutation in circulating tumor DNA demonstrates evolution during therapy for metastatic breast cancer. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7(313): 313ra182–313ra182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Turner N, Pearson A, Sharpe R. et al. FGFR1 amplification drives endocrine therapy resistance and is a therapeutic target in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2010; 70(5): 2085–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Holst F, Hoivik EA, Gibson WJ. et al. Recurrent hormone-binding domain truncated ESR1 amplifications in primary endometrial cancers suggest their implication in hormone independent growth. Sci Rep 2016; 6(1): 25521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.