Abstract

Background

Recent efforts of genome-wide gene expression profiling analyses have improved our understanding of the biological complexity and diversity of triple-negative breast cancers (TNBCs) reporting, at least six different molecular subtypes of TNBC namely Basal-like 1 (BL1), basal-like 2 (BL2), immunomodulatory (IM), mesenchymal (M), mesenchymal stem-like (MSL) and luminal androgen receptor (LAR). However, little is known regarding the potential driving molecular events within each subtype, their difference in survival and response to therapy. Further insight into the underlying genomic alterations is therefore needed.

Patients and methods

This study was carried out using copy-number aberrations, somatic mutations and gene expression data derived from the Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) and The Cancer Genome Atlas. TNBC samples (n = 550) were classified according to Lehmann’s molecular subtypes using the TNBCtype online subtyping tool (http://cbc.mc.vanderbilt.edu/tnbc/).

Results

Each subtype showed significant clinic-pathological characteristic differences. Using a multivariate model, IM subtype showed to be associated with a better prognosis (HR = 0.68; CI = 0.46–0.99; P = 0.043) whereas LAR subtype was associated with a worst prognosis (HR = 1.47; CI = 1.0–2.14; P = 0.046). BL1 subtype was found to be most genomically instable subtype with high TP53 mutation (92%) and copy-number deletion in genes involved in DNA repair mechanism (BRCA2, MDM2, PTEN, RB1 and TP53). LAR tumours were associated with higher mutational burden with significantly enriched mutations in PI3KCA (55%), AKT1 (13%) and CDH1 (13%) genes. M and MSL subtypes were associated with higher signature score for angiogenesis. Finally, IM showed high expression levels of immune signatures and check-point inhibitor genes such as PD1, PDL1 and CTLA4.

Conclusion

Our findings highlight for the first time the substantial genomic heterogeneity that characterize TNBC molecular subtypes, allowing for a better understanding of the disease biology as well as the identification of several candidate targets paving novel approaches for the development of anticancer therapeutics for TNBC.

Keywords: breast cancer, TNBC, molecular subtype, heterogeneity, genomic, transcriptomic

Key Message

Our findings highlight for the first time the substantial genomic heterogeneity that characterize TNBC molecular subtypes, allowing for a better understanding of the disease biology as well as the identification of several candidate targets paving novel approaches for the development of anticancer therapeutics for TNBC.

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), defined by the lack of expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) and the absence of HER2 overexpression and amplification, represents ∼10%–20% [1] of all breast cancers. TNBCs overall portend worse prognosis compared with other types of breast cancer with increased likelihood of early distant recurrence and death [1]. Beyond PAM50-based classification, recent efforts of genome-wide profiling have led to the recognition of six stable molecular subtypes of TNBC as described by Lehmann et al. [2] namely basal-like 1 (BL1), basal-like 2 (BL2), immunomodulatory (IM), luminal androgen receptor (LAR), mesenchymal (M) and mesenchymal stem-like (MSL). A more recent and partially overlapping classification segregated TNBC into four subtypes: basal-like/immune-suppressed (BLIS), basal-like/immune activated (BLIA), LAR and mesenchymal (MES) [3]. In a retrospective study, Masuda et al. [4] have examined the relationship between pathological complete response (pCR) and clinical outcome by TNBC subtypes using both PAM50 and Lehmann’s classification and found the latter to be a better predictor of pCR [5]. While Masuda’s study is limited by its small size and retrospective nature, it raises important considerations for the potential use of molecular subtyping to better decipher the clinical heterogeneity of TNBC.

Based on these data and in view of the limited clinical benefit with targeted therapies in unselected TNBC patients, there has been a research impetus towards optimizing treatment through molecular subtyping [6]. Little is known about the potential driving molecular events within each subtype and further insight into their underlying genomic alterations is needed. TNBCs are significantly associated with BRCA1 germline mutations and high levels of genomic instability, TP53 (82%) and PIK3CA (10%) being the two most frequently mutated somatic genes [7]. In TNBCs where actionable somatic mutations constitute low-frequency events [2, 7], mutational analyses in the context of different molecular subtypes are essential to determine whether subtype-specific therapies can be considered. Moreover, despite the large number of past and ongoing clinical trials [8] investigating therapeutic targets in TNBC, chemotherapy still is the only standard treatment option for those patients.

Here, we aimed to study the genomic aberrations that drive each of the TNBC molecular subtypes as defined by Lehmann et al. by applying an integrative analysis combining somatic mutation, copy number aberrations (CNAs) and gene expression profiles of 550 TNBC derived from Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) [9] and the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [10] consortia. To our knowledge, this is the largest study that aims to in depth characterize TNBC subtype-specific alterations, with the ultimate goal to provide novel genomic-driven therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Datasets

Bioinformatic analyses were carried out on publicly available transcriptomic and genomic data including normalized gene expression, somatic mutation calling and segmented copy-number data from 355 and 195 TNBC samples from the Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) [9] and The Cancer Genome Atlas Consortium (TCGA) [10], respectively. The types of omics data available for each patient are described in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Additional information on the bioinformatics methods used in this analysis is provided in supplementary methods. All statistical analyses were carried out using R (version 3.4.0). P-Values were corrected for multi-testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR). Statistical tests were considered significant if FDR < 0.05.

Results

Reproducibility of Lehmann’s TNBC classification in the METABRIC series

We first sought to reproduce Lehmann’s classification by applying his methods on the 550 TNBC samples (∼18%) from the METABRIC and TCGA datasets. In particular, we assessed whether we could generate similar TNBC subtypes using unsupervised k-means consensus clustering (supplementary Figure S1A–H, available at Annals of Oncology online). The optimal number of clusters based on the area under the curve of the consensus distribution function (CDF) plot was found to be 5 (supplementary Figure S1E and I, available at Annals of Oncology online). Consistently with Lehmann’s classification, the contingency tables showed the best global agreement (69%) as well as the best Cohen kappa value (k =0.52) for k = 5 (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

As shown in supplementary Figures S1E and S2, available at Annals of Oncology online, the BL1, IM, LAR, M and MSL samples overall clustered with samples from the same subtype. Of note, BL1 and M samples predominantly clustered together but also to a minor extent with samples from other subtypes. In contrast, BL2 and UNS subtypes appeared less reproducible since they were clustered non-specifically. Based on those results, we opted to remove the BL2 subtype and to re-assign BL2 samples to the second highest significant correlated centroid (supplementary Figures S2E and Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). BL2 samples were reclassified as LAR (19%), IM (15%), M (11%) and MSL (11%). After BL2 subtype removal, UNS samples were reclassified as LAR (13%), MSL (6%), BL1 (3%), IM (3%) and M (3%). Of note, 21 samples from the BL2 subtype and 44 samples from the UNS subtype remained unclassified and were removed from further analyses (supplementary Figure S2F, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of the 485 remaining samples (supplementary Figures S3A, available at Annals of Oncology online), 122 were classified as BL1 (25%), 119 as IM (25%), 102 as M (21%), 77 as LAR (16%) and 65 as MSL (13%).

Our results support the presence of five stable TNBC subtypes at the transcriptional level, namely the BL1, IM, LAR, M and MSL, which will be further investigated in the present analysis.

TNBC molecular subtypes are associated with different clinic-pathological variables and clinical outcome

We then assessed the distribution of the intrinsic molecular (PAM50) subtypes [10] within the whole TNBC cohort and within each of the five stable TNBC molecular subtypes using the PAM50 classifier. As expected, the majority of the samples were classified as basal-like (76%), followed by HER2-enriched (15%), normal-like (5%) and luminal A and B (2%) tumours (supplementary Figure S3B, available at Annals of Oncology online). When considering specific subtypes, BL1, IM and M samples were almost entirely composed of basal-like tumours whereas the LAR and MSL subtypes were composed of 75% of HER2-enriched and 28% of normal-like tumours, respectively (supplementary Figure S3C, available at Annals of Oncology online).

We also investigated the associations between classical clinic-pathological characteristics and TNBC molecular subtypes using two-sided Fisher tests. As shown in Table 1, the BL1 subtype was enriched with younger patients, whereas the LAR subtype was enriched with older patients. The BL1, IM and M subtypes were enriched with high grade tumours whereas the LAR and MSL subtypes were predominantly associated with low grade tumours. Although this cohort was mostly represented by invasive ductal carcinomas (84%), the LAR and IM subtypes were enriched with invasive lobular and invasive medullary carcinomas (supplementary Figure S3D and E, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 1.

Patient and tumour clinic-pathological characteristics within each TNBC molecular subtype

| Number of samples | ALL (%) | BL1 (%) | IM (%) | LAR (%) | M (%) | MSL (%) | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 485 (100) | 122 (25) | 119 (25) | 77 (16) | 102 (21) | 65 (13) | ||

| Age (years old) | |||||||

| <45 | 106 (22) | 40 (33) | 30 (25) | 5 (8) | 18 (18) | 13 (20) | <0.001 |

| ≥45 | 378 (78) | 82 (67) | 89 (75) | 71 (92) | 84 (82) | 52 (80) | <0.001 |

| Tumour size (cm) | |||||||

| ≤2 | 173 (36) | 41 (34) | 44 (37) | 25 (33) | 28 (27) | 35 (54) | 0.018 |

| >2 | 307 (63) | 79 (65) | 74 (62) | 52 (67) | 72 (71) | 30 (46) | 0.033 |

| Unknown | 5 (1) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Nodal status | |||||||

| Positive | 228 (47) | 63 (52) | 60 (50) | 39 (51) | 35 (34) | 31 (48) | 0.074 |

| Negative | 257 (53) | 59 (48) | 59 (50) | 38 (49) | 67 (66) | 34 (52) | 0.074 |

| Grade | |||||||

| I/II | 65 (13) | 2 (2) | 8 (7) | 19 (25) | 13 (13) | 23 (35) | <0.001 |

| III | 407 (84) | 119 (97) | 109 (92) | 58 (75) | 88 (86) | 33 (51) | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 14 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 9 (14) | <0.001 |

| Histological type | |||||||

| IDC | 406 (84) | 111 (91) | 97 (81) | 67 (87) | 90 (88) | 41 (63) | <0.001 |

| ILC | 17 (3) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 8 (10) | 1 (1) | 5 (8) | 0.001 |

| MED | 28 (6) | 6 (5) | 18 (15) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | <0.001 |

| OTHER | 33 (7) | 4 (3) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 9 (9) | 18 (28) | <0.001 |

NS, not significant.

Finally, we assessed whether molecular subtypes were associated with distinct clinical outcome. Using a Cox proportional hazards regression model, the PAM50 classification was found to be significantly associated with overall survival (supplementary Figure S3F and G, available at Annals of Oncology online), with HER2-E subtype showing the worse prognosis (HR = 1.56; CI = 1.07–2.26; P = 0.02). The LAR subtype showed a worse outcome in the univariate (HR = 1.5; CI = 1.04–2.17; P = 0.031) and the multivariate (HR = 1.47; CI = 1.0–2.14; P = 0.046) analysis whereas the IM subtype was significantly associated with a better prognosis (HR = 0.68; CI = 0.46–0.99; P = 0.043) in the multivariate analysis (supplementary Figure S3H and I, available at Annals of Oncology online).

These results demonstrate the presence of a substantial clinic-pathological heterogeneity and a distinct clinical behaviour that characterize TNBC molecular subtypes.

TNBC molecular subtypes exhibit heterogeneous mutational profiles

To gain more insight into the potential genomic abnormalities that drive this heterogeneity, we assessed the mutational profiles characterizing each of the TNBC molecular subtypes derived from targeted and whole exome sequencing. As previously described [10, 11], sequencing data were available for 447 out of the 485 (92%) TNBC tumours samples (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) allowing the identification of 2273 somatic mutations comprising 1994 point mutations and 279 small insertions/deletions (indels). No statistically significant differences were observed regarding the type of nucleotide substitutions (supplementary Figure S4A, available at Annals of Oncology online) nor effect on protein sequence (supplementary Figure S4B, available at Annals of Oncology online) between TNBC molecular subtypes. In contrast, we observed differences in terms of mutational burden. With an overall median of four exonic mutations per tumour (IQ = 3–6) (supplementary Figure S4C, available at Annals of Oncology online), the LAR subtype was characterized by a significantly higher mutational burden (FDR = 0.03) whereas the MSL was characterized by a significantly lower mutational burden (FDR = 0.012).

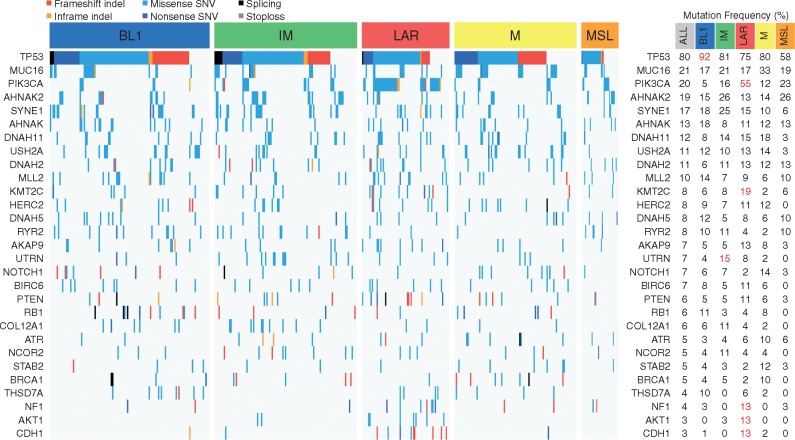

TP53 (81%), MUC16 (21%) and PIK3CA (20%) were the most frequently mutated genes in exonic regions for the global TNBC cohort (Figure 1) with the BL1 subtype showing the highest rate of TP53 mutations (92%; FDR = 0.039). Of interest, the LAR subtype showed the most distinct mutational profile when compared with other subtypes with enrichment of mutations in PIK3CA (55%; FDR = 6.8 × 10−14), KMT2C (19%; FDR = 0.023), CDH1 (13%; FDR = 2.1 × 10−4), NF1 (13%; FDR = 0.027) and AKT1 (13%; FDR = 1.1 × 10−3) genes. Consistently, AKT1 and CDH1 mutations were significantly associated with higher and lower mRNA expression levels, respectively (supplementary Figure S4D and E, available at Annals of Oncology online). Several of these mutations affected genes involved in specific KEGG signalling pathways across TNBC subtypes (supplementary Figure S4F, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

Mutational landscape of TNBC molecular subtypes. Frequencies of mutations across each TNBC molecular subtype according to the different types of mutations. Only genes mutated at a frequency >10% in at least one subtype are displayed. Significant differences (FDR < 0.05) are shown in red (right panel).

These results highlight the presence of a substantial heterogeneity at the mutational level characterizing each of the TNBC molecular subtype with potential clinical implications.

TNBC molecular subtypes display distinct genomic instability

Since TNBC tumours are known to be associated with instable genomes [10], we investigated chromosomal instability (CIN) as defined by the percentage of the genome affected by CNAs according to hormonal status (supplementary Figure S5A, available at Annals of Oncology online), PAM50 classification (supplementary Figure S5B, available at Annals of Oncology online) and within TNBC molecular subtypes (supplementary Figure S5C, available at Annals of Oncology online). As expected, ER−/HER2− as well as basal-like cancers displayed higher CIN scores when compared with the other subtypes (median CIN = 0.52 versus 0.28 for ER−/HER2− and 0.58 versus 0.28 for basal-like breast cancer; for both P < 10−16). Among the TNBC subtypes, BL1 and M tumours were the ones displaying a significantly higher median CIN scores (supplementary Figure S5D, available at Annals of Oncology online).

We also examined the frequency of CNAs in 32 known breast cancer copy number driver genes [12] in the whole TNBC cohort and across all molecular subtypes. MYC (64%), PIK3CA (51%) and CDK6 (39%) appeared to be the most frequently gained/amplified genes whereas MAP2K4 (55%), TP53 (55%) and NCOR1 (54%) were most frequently subject to hemizygous (HETD) or homozygous deletion (HOMD) across the whole TNBC cohort (Figure 2). BL1 subtype showed the highest number of CNAs (Figures 2 and 3A; supplementary Figure S6, available at Annals of Oncology online) with high gain/amplification levels involving MYC (FDR = 2.1 × 10−11), PIK3CA (FDR = 3.5 × 10−3), CDK6 (FDR = 0.012), AKT2 (FDR = 1.6 × 10−4), KRAS (FDR = 0.01), FGFR1 (FDR = 4.6 × 10−3), IGF1R (FDR = 5.9 × 10−4), CCNE1 (FDR = 5.9 × 10−4) and CDKN2A/B (FDR = 5.6 × 10−5 and 7.5 × 10−5) genes, as well as the highest frequency of HETD/HOMD in genes linked with DNA repair such as BRCA2 (FDR = 0.019), PTEN (FDR = 0.019), MDM2 (FDR = 3.9 × 10−4), RB1 (FDR = 0.042) and TP53 (FDR = 0.025). The LAR subtype was significantly associated with higher gain/amplification levels for EGFR (FDR = 1.9 × 10−3) and AKT1 (FDR = 7.9 × 10−4), as well as high frequency of HETD/HOMD for CCND3 (FDR = 4.7 × 10−3), AKT2 (FDR = 9.8 × 10−3), ESR1 (FDR = 4.7 × 10−3), CDKN2A/B (FDR = 3.5 × 10−4 and 4.6 × 10−4), SMAD4 (FDR = 2.0 × 10−3), NF1 (FDR = 0.047), NCOR1 (FDR = 1.2 × 10−4), TP53 (FDR = 7.2 × 10−5) and MAP2K4 (FDR = 8.5 × 10−5) genes. Finally, the M subtype was significantly associated with higher frequency gain/amplification levels for DNMT3A (FDR = 0.036) and TP53 (FDR = 0.034), as well as high frequency of HETD/HOMD for PDGFRA (FDR = 0.037), RB1 (FDR = 9.8 × 10−3) and MAP3K1 (FDR = 2.7 × 10−3).

Figure 2.

Genomic instability within each TNBC molecular subtype. CNA frequencies for the 32 breast cancer copy number driver genes across each TNBC molecular subtype. Significant differences (FDR < 5%, one-sided Fisher test) are shown with an asterisk.

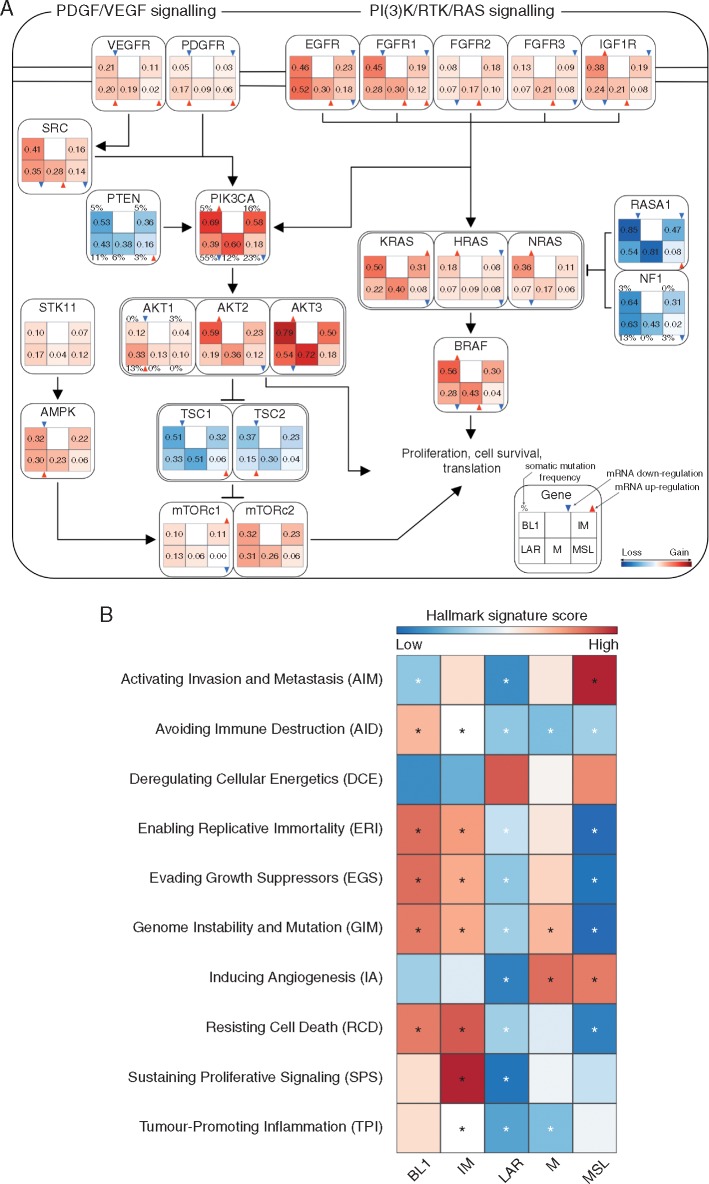

Figure 3.

Altered signalling pathways and deregulated hallmarks of cancer signatures within each TNBC molecular subtype. (A) Genomic and transcriptomic alterations profiles involving PDGF/VEGF and PI(3)K/RTK/RAS signalling pathway. Copy-number frequency is reported for each TNBC molecular subtype inside each box. Copy number gain frequency is presented in red while copy number losses are in blue. Differences in mRNA expression were tested using one-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with P-values corrected for multi-testing. Significant mRNA upregulation and downregulation were displayed using, respectively, red and blue triangles. Somatic mutation frequency is reported, when available, on top of each TNBC molecular subtype. (B) Heatmap of the 10 Hallmarks of cancer meta-gene signature scores for the TNBC molecular subtypes. Differences were reported using one-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test with P-values corrected for multi-testing. Significant differences were reported for FDR lower than 5% (significant up-regulation are displayed in black and down-regulated in white).

Similarly, to previous results, TNBC subtypes are characterized by distinct CNA profiles, notably in specific driver cancer genes, providing the basis for future genomic-driven targeted therapies.

Different biological processes characterize TNBC subtypes according to hallmarks of cancer

Here, we sought to assess the biological processes driving each TNBC molecular subtype according to the Hallmarks of Cancer [13]. For this purpose, we computed specific meta-gene signatures associated with the 10 previously reported hallmarks of Cancer using 270 Reactome signatures [14] (Figure 3B). Of interest, the BL1 subtype was significantly associated with Genome Instability and Mutation biological process (FDR = 1.3 × 10−10) whereas the IM subtype was significantly associated with Avoiding Immune Destruction process (FDR = 2.6 × 10−42) and Tumour-Promoting Inflammation (FDR = 2.7 × 10−32) processes. The M subtype was associated with Inducing Angiogenesis (FDR = 1.7 × 10−3) whereas the MSL subtype was significantly associated with Activating Invasion and Metastasis (FDR = 4.3 × 10−6) and Inducing Angiogenesis (FDR = 2.6 × 10−3) processes. The LAR subtype was not enriched in any of the signatures.

Discussion

In this study, we carried out an integrative in silico analysis using publicly available datasets in order to emphasize the degree of TNBC heterogeneity at the gene expression, mutational and CNA levels. We were able to globally reproduce Lehmann’s [2] TNBC classification with BL1, IM, LAR, M and MSL being the more stable subtypes. In particular, we showed that TNBC could be partitioned into five stable transcriptional subtypes with ∼25% being BL1, 25% IM, 16% LAR, 21% M and 13% MSL. Of note, the lack of reproducibility regarding BL2 and UNS subtypes has already been observed in other studies [4, 15].

We furthermore showed that TNBC molecular subtypes displayed distinct clinic-pathological characteristics, PAM50 and histotype distribution as well as overall survival. As already reported [7], BL1, IM and M tumours were classified as basal-like tumours whereas a substantial proportion of LAR and MSL tumours were classified as HER2-enriched and normal-like, respectively. Of interest, LAR tumours were associated with higher mutational burden with significantly enriched mutations clustered in the PI3K pathway and MSL tumours were the ones showing the lowest mutational load that could partially explain their pertaining to HER2-enriched and normal-like subtypes by PAM50, respectively.

Although this TNBC series was mostly represented by invasive ductal carcinomas, we did observe some differences with the LAR and IM subtypes being enriched with invasive lobular and medullary carcinomas, respectively. Similarly to LAR tumours, lobular cancers harbour high mutation frequency in PIK3CA, AKT1 and CDH1 genes [16] whereas medullary breast cancers, like IM tumours, are enriched with tumour infiltrating lymphocytes which are captured by high expression levels of immune check point genes and immune response signatures [17].

Moreover, we found specific differences in mutational and copy number profiles characterizing each TNBC molecular subtype offering novel therapeutic avenues for TNBC patients. For instance, we demonstrated that BL1 tumours were characterized by high genomic instability, high copy number losses for TP53, BRCA1/2 and RB1 genes, as well as high copy number gains for PPAR1 gene (supplementary Figure S6A, available at Annals of Oncology online) supporting the notion that these tumours may be sensitive to PARP inhibitors. In addition, they may also be potential candidates for MEK1/2 inhibitors since 90% of BL1 tumours displayed copy number gains for KRAS, NRAS and BRAF with significant mRNA overexpression of the corresponding genes (Figures 2 and 3A). Finally, a high proportion of BL1 may also benefit from PI3K/AKT inhibitors since they showed a high frequency of PIK3CA copy number gains with significant overexpression of PIK3CA, AKT2 and AKT3 genes (Figures 2 and 3A).

We also demonstrated that LAR and MSL tumours retained RB1 while showing significantly lower CDK4 and CDK6 mRNA expression level (supplementary Figure S6B, available at Annals of Oncology online). Since RB1, CDK4 and CDK6 expression was shown to be associated with response to CDK4/6 inhibitors [18], patients diagnosed with LAR and MSL tumours may be potential candidates to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Moreover, 75% of LAR tumours exhibited somatic mutations in PI3K signalling pathway (Figures 1 and 3A), suggesting a potential benefit to PI3K and AKT inhibitors as previously reported in preclinical models [19].

Despite being genetically more stable, MSL tumours showed an overexpression of the “Inducing Angiogenesis” hallmark together with a significant mRNA overexpression of PDGFR and VEGFR that may drive MSL tumorigenesis supporting that these tumours may derive benefit from an antiangiogenic therapy (Figure 3A and B) in contrast to unselected TNBC population [20].

EGFR and Notch signalling pathways were found to be enriched in M subtype, with high level of mRNA expression for EGFR (Figure 3A) and NOTCH1, NOTCH3 (supplementary Figure S6C, available at Annals of Oncology online) suggesting that targeting EGFR and Notch pathways may be an option for these tumours. Similarly to anti-VEGF inhibitors, EGFR inhibitors failed to demonstrate a survival advantage in unselected TNBC [21].

What differentiated IM to other TNBC subtypes was the presence of high expression levels of immune related signatures as well as high mRNA expression levels of immune check point inhibitor genes such as PD1, PDL1 and CTLA4 (supplementary Figure S6D, available at Annals of Oncology online) supporting the notion that these tumours may mostly benefit from checkpoint inhibitors.

Finally, MYC was the most frequently gained/amplified gene in almost all TNBC subtypes but MSL, in association with a significant mRNA overexpression in the BL1 and M subtypes (supplementary Figure S6E and F, available at Annals of Oncology online). It has been recently shown that selective inhibition of CDK1/2 [22] and spliceosomal core component BUD31 [23] was found to induce synthetic lethal mortality in MYC overexpressing TNBC tumours suggesting a potential benefit of inhibiting CDK1/2 and the spliceosome, in particular in the BL1 and M subtypes.

In conclusion, our findings highlight for the first time the substantial biological heterogeneity that characterize TNBC molecular subtypes at the somatic mutation, copy number and gene expression levels, allowing the identification of several candidate targets paving novel approaches for the development of anticancer therapeutics for TNBC.

Funding

YB and CS are supported by the Télévie and the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (F.R.S.-FNRS). DV is partly supported by a grant of the Région Wallonne. This study was supported by a grant from Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF). No grant numbers applied.

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD. et al. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California Cancer Registry. Cancer 2007; 109(9): 1721–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehmann BDB. et al. Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 2750–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burstein MD, Tsimelzon A, Poage GM. et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies novel subtypes and targets of triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21(7): 1688–1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Masuda H, Baggerly KA, Wang Y. et al. Differential response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy among 7 triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19(19): 5533–5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Schafer JM. et al. PIK3CA mutations in androgen receptor-positive triple negative breast cancer confer sensitivity to the combination of PI3K and androgen receptor inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res 2014; 16(4): 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baselga J. et al. Randomized phase II study of the anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody cetuximab with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 2586–2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lehmann BD, Pietenpol JA.. Clinical implications of molecular heterogeneity in triple negative breast cancer. Breast 2015; 24: S36–S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016; 13(11): 674–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curtis C. et al. The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2, 000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups. Nature 2012; 486: 346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koboldt DC, Fulton RS, McLellan MD. et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012; 490(7418): 61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pereira B, Chin S-F, Rueda OM. et al. The somatic mutation profiles of 2,433 breast cancers refines their genomic and transcriptomic landscapes. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nik-Zainal S, Davies H, Staaf J et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature 2016; 534: 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA.. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011; 144(5): 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Iorio F, Garcia-Alonso L, Brammeld J. et al. Pathway-based dissection of the genomic heterogeneity of cancer hallmarks with SLAPenrich. bioRxiv 2016; 077701. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/077701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Tseng L-M, Chiu J-H, Liu C-Y. et al. A comparison of the molecular subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer among non-Asian and Taiwanese women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017; 163(2): 241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desmedt C, Zoppoli G, Gundem G. et al. Genomic characterization of primary invasive lobular breast cancer. JCO 2016; 34(16): 1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malyuchik SS, Kiyamova RG.. Medullary breast carcinoma. Exp Oncol 2008; 30(2): 96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raspé E, Coulonval K, Pita JM. et al. CDK4 phosphorylation status and a linked gene expression profile predict sensitivity to palbociclib. EMBO Mol Med 2017; 9(8): 1052–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Asghar US, Barr AR, Cutts R. et al. Single-cell dynamics determines response to CDK4/6 inhibition in triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(18): 5561–5572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cameron D, Brown J, Dent R. et al. Adjuvant bevacizumab-containing therapy in triple-negative breast cancer (BEATRICE): primary results of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(10): 933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carey LA, Rugo HS, Marcom PK. et al. TBCRC 001: randomized phase II study of cetuximab in combination with carboplatin in stage IV triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(21): 2615–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horiuchi D, Kusdra L, Huskey NE. et al. MYC pathway activation in triple-negative breast cancer is synthetic lethal with CDK inhibition. J Exp Med 2012; 209(4): 679–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hsu TY-T, Simon LM, Neill NJ. et al. The spliceosome is a therapeutic vulnerability in MYC-driven cancer. Nature 2015; 525(7569): 384–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.