Abstract

Objective

RA patients who have failed biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) represent an unmet medical need. We evaluated the effects of baseline characteristics, including prior bDMARD exposure, on baricitinib efficacy and safety.

Methods

RA-BEACON patients (previously reported) had moderate to severe RA with insufficient response to one or more TNF inhibitor and were randomized 1:1:1 to once-daily placebo or 2 or 4 mg baricitinib. Prior bDMARD use was allowed. The primary endpoint was a 20% improvement in ACR criteria (ACR20) at week 12 for 4 mg vs placebo. An exploratory, primarily post hoc, subgroup analysis evaluated efficacy at weeks 12 and 24 by ACR20 and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) ⩽10. An interaction P-value ⩽0.10 was considered significant, with significance at both weeks 12 and 24 given more weight.

Results

The odds ratios predominantly favored baricitinib over placebo and were generally similar to those in the overall study (3.4, 2.4 for ACR20 weeks 12 and 24, respectively). Significant quantitative interactions were observed for baricitinib 4 mg vs placebo at weeks 12 and 24: ACR20 by region (larger effect Europe) and CDAI ⩽10 by disease duration (larger effect ⩾10 years). No significant interactions were consistently observed for ACR20 by age; weight; disease duration; seropositivity; corticosteroid use; number of prior bDMARDs, TNF inhibitors or non-TNF inhibitors; or a specific prior TNF inhibitor. Treatment-emergent adverse event rates, including infections, appeared somewhat higher across groups with greater prior bDMARD use.

Conclusion

Baricitinib demonstrated a consistent, beneficial treatment effect in bDMARD-refractory patients across subgroups based on baseline characteristics and prior bDMARD use.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), NCT01721044

Keywords: baricitinib, biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, insufficient response, Janus kinase inhibitor, rheumatoid arthritis, RA-BEACON, subgroup analysis, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

Rheumatology key messages

New therapeutic options are needed for RA patients with an insufficient response to biologic DMARDs.

In RA-BEACON, baricitinib compared with placebo improved functional and clinical outcomes in biologic DMARD–refractory patients.

Benefits were observed for baricitinib across subgroups defined by baseline characteristics, including prior biologic DMARD use.

Introduction

RA-BEACON was a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of baricitinib, an oral highly selective Janus kinase 1 and 2 inhibitor, in patients who had moderately to severely active RA, an insufficient response or intolerance to at least one biologic TNF inhibitor and were taking background conventional DMARD (cDMARD) therapy with or without MTX (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01721044) [1]. This study enrolled a high proportion of patients (more than one-third) with an inadequate response to or unacceptable side effects associated with both TNF inhibitor and non-TNF inhibitor biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs); only a minority of the studied individuals (∼40%) had failed solely one bDMARD. Thus our study population had particularly refractory disease, having mostly received multiple previous biologic therapies [1]. At week 12, the time of the primary endpoint, baricitinib-treated patients had significantly better functional and clinical responses, including attainment of low disease activity, than placebo-treated patients [1].

Achieving low disease activity is the major therapeutic target today in patients with established RA [2, 3]. A substantial percentage of patients with established RA have utilized many DMARD therapies and failed to achieve a low disease activity state. Clinical trials have similarly revealed that response rates to all currently used agents decrease with increasing cDMARD and bDMARD experience [4]. Trials in patients who have failed previous bDMARDs are of particular importance because this population is progressively increasing and has the greatest unmet need within the realm of RA. The extent to which patient characteristics, such as past use of specific bDMARDs, age, disease duration or serological status influence the response to baricitinib was not previously assessed in the RA-BEACON study [1]. These important questions are addressed in the present analyses.

Methods

Study population and design

Patients were ⩾18 years old, with moderately to severely active RA (⩾6/68 tender joints and ⩾6/66 swollen joints; serum high-sensitivity CRP level ⩾3 mg/l) and must have previously received one or more TNF inhibitor and discontinued treatment because of either insufficient response or intolerance. The protocol did not otherwise place restrictions on the number or type of prior bDMARDs used. All bDMARDs must have been discontinued ⩾4 weeks prior to randomization (⩾6 months for rituximab). At study entry, patients must have had regular use of one or more cDMARD at stable doses and continued cDMARDs as background therapy. The full results of the RA-BEACON study have been previously described [1]. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and was approved by each centre’s institutional review board or ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent.

Qualifying patients were randomly assigned 1:1:1 to once-daily placebo or baricitinib at a daily dose of 2 or 4 mg for 24 weeks. Two strata were incorporated into randomization, geographic region and the number of prior bDMARDs used (categorized as less than three or three or more). The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients achieving a 20% improvement in ACR criteria (ACR20) for baricitinib 4 mg vs placebo at week 12 [1]. Rescue (baricitinib 4 mg) was assigned at week 16 to patients who did not have at least a 20% improvement in tender and swollen joint counts at weeks 14 and 16. After week 16, patients could receive rescue treatment at the investigator’s discretion on the basis of joint counts.

Subgroups

The current subgroup analysis was undertaken to evaluate the effect of prior bDMARD history, last bDMARD used, number and type of bDMARD ever received, baseline demographics and clinical characteristics on the efficacy and safety of baricitinib in this population of patients, a large proportion of whom (more than one-third) had a history of an inadequate response to or intolerance associated with both TNF inhibitor and non-TNF inhibitor bDMARDs. The primary study population had high disease activity at baseline with 28-joint DAS based on high-sensitivity CRP level (DAS28-CRP) mean scores of >5.1 and HAQ–Disability Index (HAQ-DI) mean scores of >1.5 [1].

Prespecified subgroups included baseline demographic and clinical characteristics such as age, weight, geographic region, disease duration, seropositivity (RF or ACPA positive; both RF and ACPA negative), corticosteroid use and the number of prior bDMARDs (less than three or three or more).

Additional subgroups were defined post hoc to further evaluate the effect of prior bDMARD use on efficacy and safety: the number of prior TNF inhibitors (categorized 1, ⩾2); the number of prior non-TNF inhibitors used (categorized 0, ⩾1); among patients naïve to non-TNF inhibitor, the number of prior TNF inhibitors used (categorized 1, ⩾2); specific prior bDMARDs and the last bDMARD used prior to randomization. To explore the influence of baseline disease activity on response, efficacy was also evaluated post hoc by baseline Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score tertiles. To further investigate the impact of baseline serostatus, efficacy was evaluated by all four possible combinations of RF and ACPA.

Efficacy between strata in various subgroups was assessed at week 12 (the time of the primary endpoint assessment) and week 24 by the percentage of patients who had an ACR20 response and/or low disease activity measured by a CDAI ⩽10. The CDAI ⩽10 efficacy analyses were conducted post hoc. Safety assessments included adverse events in patients treated with one or more than one TNF inhibitor and less than three or three or more bDMARDs. In this subgroup, analyses data are provided for both the baricitinib 2 and 4 mg groups, with the primary focus on baricitinib 4 mg.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis methods for the overall study have been previously described [1]. In the current subgroup analysis, comparisons between each baricitinib group and placebo group were performed across subgroups at weeks 12 and 24 on the modified intention-to-treat population, which was defined as all randomized patients who received at least one dose of study drug. Subgroup analyses based on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (excluding the CDAI tertile) for the ACR20 efficacy measure were prespecified while the rest were post hoc.

For the categorical outcomes, non-responder imputation was used in the analysis for patients who received rescue therapy or discontinued from the study or study treatment. A logistic regression model (treatment group + subgroup + treatment by subgroup) was used to detect significant interactions between treatment and subgroups. An interaction P-value ⩽0.10 was considered statistically significant. When the sample size requirements were not met (less than five responders in any treatment group for any subgroup), the interaction P-value was not calculated. Within a subgroup, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs are from a logistic regression model: treatment group. When the sample size requirements were not met (less than five responders in any treatment group), the P-values from the Fisher’s exact test were used instead of the OR and 95% CI.

Interpretation of subgroup interaction analyses that had a P-value ⩽0.10 began with an examination of the direction (same as or opposite to overall treatment effect) and then the magnitude of the treatment effect across the strata. Interactions are characterized as quantitative (treatment effect is consistent in direction, but not magnitude, in all strata) or qualitative (effect is beneficial in some, but not all, strata). More weight was given to interactions that were evident at both weeks 12 and 24 to minimize overinterpretation of any difference that could be due to chance.

Some subgroups included strata with small numbers of patients (such as evaluation by last bDMARD used and by prior specific bDMARD use). Although these subgroups did not have a sufficient sample for formal statistical comparisons, data within each subgroup were summarized to provide information for this refractory patient population.

Results

Full details of the randomized, double-blind RA-BEACON trial design have been reported previously [1]. Data are presented for the baricitinib 2 and 4 mg treatment groups compared with placebo, although the primary comparison is for the 4 mg dose compared with placebo.

Patient characteristics

Demographics and disease-related clinical characteristics were similar among treatment groups at baseline [1]. Patients were predominantly female (∼82%) and Caucasian (83%), with a mean age of ∼56 years, RA duration of 14 years, CDAI of ∼41 and DAS28-CRP of ∼5.9 [1]. Approximately 82% of patients had concomitant MTX use [1].

Patients had been previously treated with at least one TNF inhibitor for study entry and many had a history of treatment with multiple TNF inhibitors (59, 31 and 9% for one, two or three or more TNF inhibitors, respectively) [1]. Etanercept, adalimumab and infliximab were the most commonly used prior TNF inhibitors (supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). Six patients (1%) had not received a prior TNF inhibitor (protocol deviation). Looking at all prior bDMARDs, a patient could have been treated with one or more TNF inhibitors and none, one or more than one non-TNF bDMARD. The percentages of patients treated with one, two or three or more licensed bDMARDs (TNF inhibitor or non-TNF inhibitor) of any kind were 42, 30 and 27%, respectively [1]. This means that although 59% of patients had received only one prior TNF inhibitor, a smaller percentage—42%—had received only one prior bDMARD. The difference of 17% indicates that these patients treated with only one prior TNF inhibitor were also treated with a prior non-TNF inhibitor. The percentage of patients who had reported prior use of one, two or three or more licensed non-TNF inhibitor bDMARDs was also notable: 24, 8 and 6%, respectively [1]. Abatacept, tocilizumab and rituximab were the most commonly used licensed non-TNF inhibitor bDMARDs (supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). In addition, nearly 10% of the patients had previously received a non-approved investigational drug, including fostamatinib, tabalumab, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, ixekizumab, secukinumab, olokizumab, canakinumab, IFN and sarilumab.

Primary study results

As previously described, the primary objective in the RA-BEACON study was met: statistically significantly more patients achieved ACR20 response at week 12 with baricitinib 4 mg compared with placebo (55% vs 27%; P ⩽ 0.001) [1]. Significantly more patients also achieved ACR20 response with baricitinib 4 mg than placebo at week 24. The percentage of patients with a CDAI ⩽10 was statistically significantly higher for baricitinib 4 mg than placebo at weeks 12 and 24 [1]. Additionally, comparing baricitinib 2 mg to placebo, significantly more patients achieved an ACR20 at week 12 (49% vs 27%; P ⩽ 0.001) and week 24 and significantly more patients achieved a CDAI ⩽10 at week 12 but not week 24 [1].

Efficacy by baseline characteristics

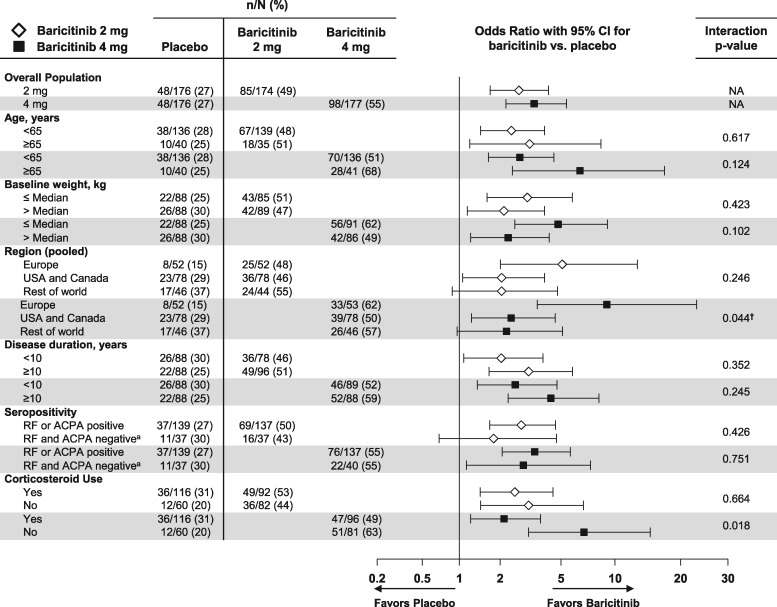

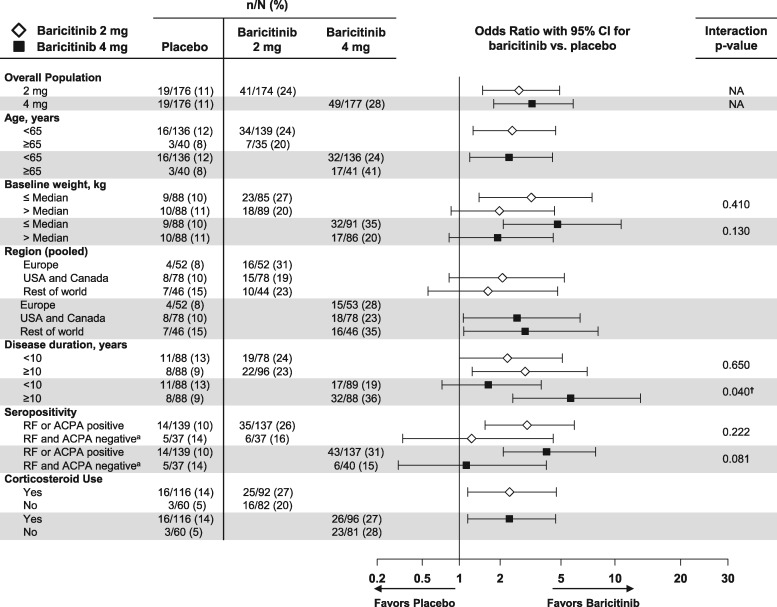

Clinical efficacy outcomes as measured by ACR20 and CDAI ⩽10 by patient baseline demographics and clinical characteristics at week 12 are described in Figs 1 and 2, respectively. No significant interactions were consistently noted for age, weight, seropositivity or corticosteroid use for ACR20 or CDAI ⩽10 between baricitinib 4 mg and placebo or baricitinib 2 mg and placebo at weeks 12 or 24 (among the CDAI ⩽10 subgroups with sufficient sample size to produce interaction P-values) (week 24 data in supplementary Figs S1 and S2, available at Rheumatology online). A large majority of seropositive patients (83%) were positive for both RF and ACPA; analyses by all four possible individual combinations of RF and ACPA for ACR20 and CDAI ⩽10 did not change conclusions (supplementary Fig. S3A–D, available at Rheumatology online). Note that patients who were RF−/ACPA− were observed to have less treatment effect compared with placebo than other serostatus combination subgroups, although the sample size was relatively small.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of patients achieving ACR20 response at week 12: patient demographic and clinical characteristics subgroups

Data (non-responder imputation) are presented as n/N (%). †The interaction of treatment with subgroup is significant (P ≤ 0.1) at both weeks 12 and 24. aFor determining seropositivity status, the ACPA-negative group includes patients with negative (≤7 U/ml) and indeterminate (>7 and ≤10 U/ml) values. N: number of patients in the specified subgroup; n: number of patients in the specified category; NA: interaction analysis not applicable.

A quantitative interaction was observed for the treatment comparison of ACR20 response between the baricitinib 4 mg group vs placebo by region (a larger treatment effect was observed for Europe) at weeks 12 and 24 (Fig. 1 and supplementary Fig. S1, available at Rheumatology online, respectively). A quantitative interaction was observed for CDAI ⩽10 for baricitinib 4 mg vs placebo by disease duration (larger treatment effect for ⩾10 years) at weeks 12 and 24 (Fig. 2 and supplementary Fig. S2, available at Rheumatology online, respectively). No quantitative interactions were observed for baricitinib 2 mg vs placebo at weeks 12 and 24 by baseline demographic or disease-related characteristics subgroups. No significant qualitative interactions were observed for either dose or placebo.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of patients achieving CDAI ≤10 at week 12: patient demographic and clinical characteristics subgroups

Data (non-responder imputation) are presented as n/N (%). †The interaction of treatment with subgroup is significant (P ≤ 0.1) at both weeks 12 and 24. aFor determining seropositivity status, the ACPA-negative group includes patients with negative (≤7 U/ml) and indeterminate (>7 and ≤10 U/ml) values. N: number of patients in the specified subgroup; n: number of patients in the specified category; NA: interaction analysis not applicable.

No significant interactions were observed for ACR20 at week 12 or 24 for either dose or placebo based on the patients’ baseline CDAI tertile (supplementary Fig. S4, available at Rheumatology online). A small sample size precluded the calculation of P-values for CDAI ⩽10 based on the baseline CDAI tertile (supplementary Fig. S5, available at Rheumatology online).

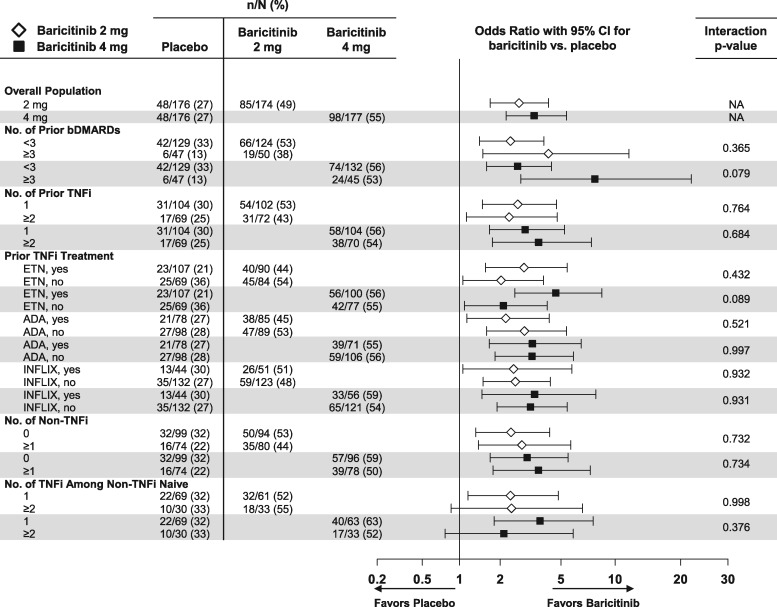

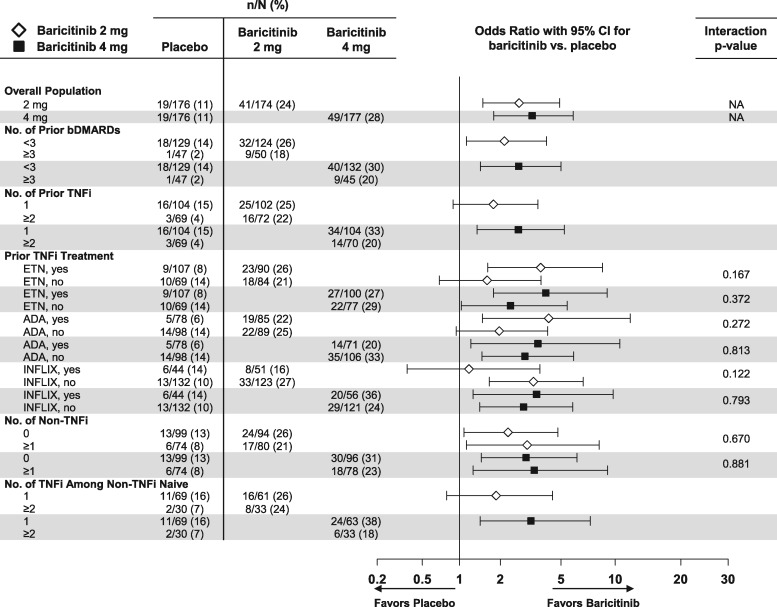

Efficacy by prior and last experience with bDMARDs

Clinical efficacy outcomes as measured by ACR20 and CDAI ⩽10 at weeks 12 and 24 by the patient’s prior cumulative experience with bDMARDs were evaluated. In the majority of cases, prior bDMARDs were discontinued due to a lack of efficacy (no response or loss of response) and a few people failed for reasons other than efficacy (supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online). For ACR20, no significant interactions between baricitinib 2 or 4 mg and placebo were consistently noted at weeks 12 and 24 based on the patient’s prior experience by the number of prior bDMARDs, number of prior TNF inhibitors (including number of TNF inhibitors among non-TNF inhibitor–naïve patients), number of prior non-TNF inhibitor treatments or specific prior TNF inhibitor (Fig. 3 and supplementary Fig. S6, available at Rheumatology online). For a CDAI ⩽10, no significant interactions for baricitinib 4 mg compared with placebo were consistently noted at weeks 12 and 24 based on the specific prior TNF inhibitor or the number of prior non-TNF inhibitors; the small sample size precluded the assessment of interaction P-values for the other subgroups (Fig. 4 and supplementary Fig. S7, available at Rheumatology online). No significant interactions were observed for baricitinib 2 mg compared with placebo for the above subgroups.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of patients achieving ACR20 response at week 12: subgroups defined by previous bDMARD experience

Data (non-responder imputation) are presented as n/N (%). ADA: adalimumab; ETN: etanercept; INFLIX: infliximab; N: number of patients in the specified subgroup; n: number of patients in the specified category; NA: interaction analysis not applicable.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of patients achieving CDAI ≤10 at week 12: subgroups defined by previous bDMARD experience

Data (non-responder imputation) are presented as n/N (%). ADA: adalimumab; ETN: etanercept; INFLIX: infliximab; N: number of patients in the specified subgroup; n: number of patients in the specified category; NA: interaction analysis not applicable.

Evidence of efficacy by ACR20 and CDAI ⩽10 at weeks 12 and 24 was also consistently observed for baricitinib 2 or 4 mg compared with placebo across subgroups based on prior use of different specific non-TNF inhibitor bDMARDs (supplementary Fig. S8 A–D, available at Rheumatology online). This included 102 patients who had previously received the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (supplementary Fig. S8A and B, available at Rheumatology online), including those (80/102) who had discontinued due to lack of efficacy (data not shown). When evaluating ACR20 response at weeks 12 and 24 by the patient’s last bDMARD prior to randomization, numerically higher response rates were found for baricitinib 2 and 4 mg compared with placebo regardless of which TNF inhibitor or non-TNF inhibitor was used most recently before enrolment in the study, with the exception of 2 mg for the last infliximab use (supplementary Fig. S9 and S10, available at Rheumatology online). No statistical assessment was performed due to the small sample sizes in these subgroups.

Safety

Detailed safety findings have been presented elsewhere [1]. Briefly, in the overall study, adverse event rates for the baricitinib 2 and 4 mg dose groups compared with placebo were 71, 77 and 64%, respectively, which included infections (44, 40 and 31%, respectively). Serious adverse event rates were similar (4, 10 and 7% for baricitinib 2 and 4 mg dose groups and placebo, respectively) [1]. In RA-BEACON, serious infections were infrequent and similar among patients who received baricitinib 2 or 4 mg compared with placebo (2, 3 and 3%, respectively) [1] and no tuberculosis infections were reported.

An evaluation of adverse events by select subgroups (one or more than one TNF inhibitor among non-TNF inhibitor–naïve patients, or less than three or three or more prior bDMARDs) showed no increase in serious infections for either baricitinib dose compared with placebo according to prior biologic use, including patients who had received multiple prior biologics, from weeks 0 to 24 (Table 1). Rates of treatment-emergent adverse events, overall infections and serious adverse events appeared somewhat higher across treatment groups (including placebo) in patients with a more extensive history of bDMARD use (three or more vs less than three prior bDMARDs) (Table 1). There are limitations to the interpretation of these data due to the relatively small number of patients in the subgroup of three or more prior bDMARDs.

Table 1 Adverse events: select subgroups from weeks 0 to 24

| One TNF inhibitor or non-TNF inhibitor naïve | More than one TNF inhibitor or non-TNF inhibitor naïve | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Placebo (n = 69) | Baricitinib 2 mg (n = 61) | Baricitinib 4 mg (n = 63) | Placebo (n = 30) | Baricitinib 2 mg (n = 33) | Baricitinib 4 mg (n = 33) |

| SAEsa | 4 (6) | 1 (2) | 4 (6) | 1 (3) | 0 | 4 (12) |

| Serious infections | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6) |

| TEAEs | 42 (61) | 39 (64) | 46 (73) | 21 (70) | 23 (70) | 24 (73) |

| Infections | 19 (28) | 21 (34) | 23 (37) | 9 (30) | 15 (45) | 8 (24) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less than three prior bDMARDs | Three or more prior bDMARDs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 129) | Baricitinib 2 mg (n = 124) | Baricitinib 4 mg (n = 132) | Placebo (n = 47) | Baricitinib 2 mg (n = 50) | Baricitinib 4 mg (n = 45) | |

| SAEsa | 9 (7) | 3 (2) | 11 (8) | 4 (9) | 4 (8) | 7 (16) |

| Serious infections | 4 (3) | 1 (<1) | 4 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) |

| TEAEs | 79 (61) | 81 (65) | 98 (74) | 33 (70) | 42 (84) | 39 (87) |

| Infections | 38 (29) | 47 (38) | 49 (37) | 17 (36) | 29 (58) | 21 (47) |

| Deathb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) |

Data displayed as n (%) of patients up to the time of rescue.

SAE: serious adverse event; TEAE: treatment-emergent adverse event.

SAEs reported using conventional ICH definitions.

One death occurred in association with basilar artery thrombosis in a 76-year-old patient with pre-existing diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

Current literature includes multiple completed phase 3 studies in the patient population with prior inadequate response or intolerance to one or more approved TNF inhibitors [5–8], but fewer also included prior use of non-TNF inhibitors [9]. With increasing therapeutic options and strategies for the treatment of RA, we have seen that the majority of patients achieve at least some level of improvement in their disease activity. However, not all patients achieve or maintain adequate responses. The most troubling group remains those patients with active disease despite the use of TNF inhibitors or other biologic agents. Clinicians face the challenge of identifying whether one subgroup of patients is more or less likely to respond to the next therapeutic option prescribed.

The RA-BEACON trial was carried out in patients with active RA despite receiving conventional DMARD therapy and prior treatment with at least one TNF inhibitor and often with experience with several other bDMARDs. On a group level, baricitinib was able to demonstrate meaningful benefit in this difficult-to-treat RA population [1]. However, to better understand the potential utility of baricitinib, population subgroup analyses were performed across a variety of patient demographic, clinical characteristic, regional origin and prior drug exposure domains. To minimize overinterpretation of a difference observed at any one time point, which could be due to chance, weight was given to variables with significance at both weeks 12 and 24.

The forest plots provide a visual representation of the likelihood of benefit across a range of subgroups treated daily with baricitinib 2 or 4 mg or placebo as demonstrated using both ACR20 and CDAI ⩽10 (low disease activity) as outcome measures of change in disease activity at weeks 12 and 24. In virtually all the subgroups assessed we saw the ORs favouring the use of baricitinib over placebo (with background cDMARDs), regardless of the number or type of bDMARD ever received. Published literature indicates that RA patients who are serologically positive for autoantibodies respond better to rituximab than those who are seronegative [10] and that bDMARD-naïve patients who are seropositive respond better to abatacept than those who are seronegative [11]. However, comparatively few patients were seronegative in this study and, importantly, no consistently statistically significant treatment × subgroup interactions were observed in the seropositivity subgroup (RF+ or ACPA+, RF− and ACPA−). Interestingly, we saw ORs favouring the efficacy of baricitinib independent of the number of TNF inhibitors previously used or the number of non-TNF inhibitor bDMARDs previously used. This differs somewhat from other bDMARDs, since decreasing responses were observed with higher numbers of prior TNF inhibitor failures for abatacept [12], golimumab [8] and rituximab [13]. Similarly, we see efficacy demonstrated independent of the last bDMARD that the patient used, which illustrates the broad nature of subgroups benefiting from therapy in this study and is particularly relevant given the unmet need for effective treatment in patients with inadequate disease control despite prior treatment with one or more biologic agents of differing types. It is also of interest that baricitinib appeared similarly efficacious in patients refractory to the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab as in those with prior use of other bDMARDs, a finding consistent with the concept that baricitinib exerts its efficacy through mechanisms that are broader than simply IL-6 pathway inhibition [14].

Efficacy is important, but adverse events are equally important in this study population with longstanding disease. Consistent with their increased exposure to prior immunosuppression, a small numerical increase in selected adverse event rates is observed in the patients with prior experience of three or more bDMARDs compared with patients with less exposure to multiple biologic agents. However, this was seen for placebo as well as for baricitinib, without a consistent increase in between-treatment group adverse event rate differences for the most extensively pretreated patients.

There are limitations to both this study and the types of analyses performed. The time frame for interpretation of safety data is limited to 24 weeks. The seronegative population is much smaller than the seropositive group, which resembles real-world patterns. The lack of radiographic endpoints limits the ability to draw conclusions regarding the capacity of baricitinib to slow the rate of structural joint damage across the subgroups included in this analysis. Perhaps most importantly, in this analysis we studied multiple subgroups and as such we have relatively small numbers on which to base any assumptions. We have not adjusted for multiple comparisons, but we did note that significant interaction P-values were observed infrequently and inconsistently, indicating minimal treatment heterogeneity across subgroups, including those defined by prior bDMARD use.

Conclusion

In this exploratory analysis of prior bDMARD use in the TNF inhibitor inadequate responder population of patients with RA, a beneficial treatment effect for baricitinib 2 or 4 mg compared with placebo was observed across subgroups irrespective of the number or nature of prior bDMARD use and, in general, a consistent treatment effect was observed across the strata with no evidence of any qualitative interactions at weeks 12 and 24. Because the population of RA patients who are TNF inhibitor inadequate responders is increasing, this finding may be clinically relevant.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Cate Jones, PhD, for assistance with tables, manuscript preparation, and process support, and Julie Sherman, AAS, for assistance with figures, both of Eli Lilly and Company.

Funding: This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Incyte.

Disclosure statement: J.M.K. has an equity interest in Corrona. He consults for AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Novartis and Pfizer and has received research grant support from all of these companies but GlaxoSmithKline. W.L.M., T.P.R. and T.C. are employees of Eli Lilly. D.E.S. is an employee and shareholder of Eli Lilly. J.S. has received grants for his institution from AbbVie, Janssen, Eli Lilly, MSD, Pfizer and Roche and has provided expert advice to and/or had speaking engagements for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Astro, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Chugai, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, ILTOO Pharma, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Medimmune, MSD, Novartis-Sandoz, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Sanofi and UCB. L.X. is an employee of Eli Lilly and owns stock and stock options in Eli Lilly. C.E.K. is an employee of Eli Lilly and may own shares/stock. C.-S.Y. is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. M.C.G. has received grant/research support or consulting support from AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, Pfizer and Vertex Pharmaceuticals. H.-P.T. reports personal fees from Roche Pharma, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Chugai, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, Eli Lilly, MSD and AstraZeneca. All other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O. et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1243–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr. et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smolen JS, Aletaha D.. Rheumatoid arthritis therapy reappraisal: strategies, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:276–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Genovese MC, Schiff M, Luggen M. et al. Efficacy and safety of the selective co-stimulation modulator abatacept following 2 years of treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:547–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen SB, Emery P, Greenwald MW. et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP. et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1516–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smolen JS, Kay J, Doyle MK. et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with tumour necrosis factor α inhibitors (GO-AFTER study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Lancet 2009;374:210–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C. et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690, 550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:451–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Isaacs JD, Cohen SB, Emery P. et al. Effect of baseline rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody serotype on rituximab clinical response: a meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:329–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alten R, Nüßlein H, Galeazzi M. et al. Baseline autoantibodies preferentially impact abatacept efficacy in patients with RA who are biologic naïve: 6-month results from a real-world, international, prospective study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67(Suppl 10):465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schiff M, Kelly S, Le Bars M, Genovese M.. Efficacy of abatacept in RA patients with an inadequate response to anti-TNF therapy regardless of reason for failure, or type or number of prior anti-TNF therapy used. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67(Suppl 2):337. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kremer JM, Tony H, Tak PP, Luggen M, Mariette X, Hessey E.. Efficacy of ritumixab in active RA patients with an inadequate response to one or more TNF inhibitors. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65(Suppl 2):326. [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Shea JJ, Holland SM, Staudt LM.. JAKs and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.