Abstract

Background

There is no standard first-line chemotherapy for recurrent/metastatic (RM) or unresectable locally advanced (LA) salivary gland carcinoma (SGC).

Patients and methods

We conducted a single institution, open-label, single arm, phase II trial of combined androgen blockade (CAB) for androgen receptor (AR)-positive SGC. Leuprorelin acetate was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 3.75 mg every 4 weeks. Bicalutamide was administered orally at a daily dose of 80 mg. Patients were treated until progressive disease or unacceptable toxicities.

Results

Thirty-six eligible patients were enrolled. Thirty-three patients had RM disease and three patients had LA disease. The pathological diagnoses were salivary duct carcinoma (34 patients, 94%) and adenocarcinoma, NOS (two patients, 6%). The best overall response rate was 41.7% [n = 15, 95% confidence interval (CI), 25.5%–59.2%], the clinical benefit rate was 75.0% (n = 27, 95% CI, 57.8%–87.9%). The median progression-free survival was 8.8 months (95% CI, 6.3–12.3 months) and the median overall survival was 30.5 months (95% CI, 16.8 months to not reached). Additional analyses between treatment outcomes and clinicopathological factors or biomarkers including AR positivity, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status, and its complex downstream signaling pathway gene mutations showed no statistically significant differences. Elevated grade 3 liver transaminases and increased serum creatinine were reported in two patients, respectively. Discontinuation of leuprorelin acetate or bicalutamide due to adverse event occurred in one patient.

Conclusion

This study suggests that CAB has equivalent efficacy and less toxicity for patients with AR-positive RM or unresectable LA SGC compared with conventional chemotherapy, which warrants further study.

Clinical Trial Registration

UMIN-CTR (http://www.umin.ac.jp/ctr/index-j.htm), identification number: UMIN000005703

Keywords: combined androgen blockade, androgen deprivation therapy, salivary duct carcinoma, salivary gland cancer, androgen receptor

Key Message

Combined androgen blockade may have antitumor activity in androgen receptor (AR)-positive salivary gland carcinoma (SGC). We conducted a prospective phase II trial to assess the benefits of a combination of leuprorelin acetate and bicalutamide in 36 patients with AR-positive, unresectable SGC. We found a >40% objective response rate, implying that further randomized trials are warranted.

Introduction

Salivary gland carcinoma (SGC) is a rare malignant tumor that accounts for 0.2%–0.3% of all malignant neoplasms and 8% of all head and neck cancers [1–3]. SGC spans a wide spectrum of histologic types, with a far greater variety than other cancers [4]. Although the biological behaviors differ markedly between histologic types, surgical resection is the conventionally accepted approach for all types, and postoperative radiation therapy is usually carried out for high-grade malignancies [4, 5]. Although a variety of chemotherapies and molecular-targeted therapies have been tested as systemic treatments for SGC, the standard regimen has not yet been established [4, 6].

Because androgen receptor (AR) expression is observed in some cases of SGC, especially in salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) [7–12], several case reports and retrospective studies with hormone therapy targeting the AR have been published [13–20]. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), the standard treatment of advanced prostate cancer, is administered using luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LH-RH) agonists or antagonists, which suppress androgen production mainly in the testes. To eliminate the effects of the small amounts of androgen secreted by the adrenal glands, combined androgen blockade (CAB), which adds an AR antagonist, such as bicalutamide or flutamide, is commonly administered [21, 22]. Recent studies employing molecular analyses including whole-exome sequencing in SDCs have suggested that CAB should be considered in the majority of SDCs [9, 10]; however, no prospective study has been conducted due to the low incidence of SDC [1–3].

In this study, we conducted a phase II trial on CAB that combined the LH-RH agonist leuprorelin acetate with the AR antagonist bicalutamide in AR-positive SGCs.

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a prospective open-label, single-arm, phase II, single institution study. We conducted this study in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided their written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of the International University of Health and Welfare at Mita Hospital. This study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) in Japan (Study ID: UMIN 000009437).

Patients

Patients who met the following criteria were enrolled: (i) recurrent/metastatic (RM) or unresectable locally advanced (LA) AR-positive SGC; unresectable tumor fulfilling at least one of the following conditions: (a) primary lesion of T4b, (b) cervical lymph node metastasis of N2c or N3 (UICC/TNM, 7th edition), and (c) cervical lymph node metastasis invading the carotid artery; (ii) ≥20 years of age; (iii) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2; (iv) an adequate organ function; (v) at least a 2-week interval from the previous treatment; (vi) measurable lesion(s) according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1; (vii) at least a 3-month life expectancy; and (viii) able to provide written consent. There were no restrictions on the number or type of previous systemic treatments, except for leuprorelin acetate or bicalutamide.

Treatment

Leuprorelin acetate was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 3.75 mg every 4 weeks. A dose of 11.25 mg every 12 weeks was permitted if the patient desired. Bicalutamide was orally administered at a daily dose of 80 mg. Patients were treated until progressive disease (PD), unacceptable toxicities, or patient refusal were noted. The administration of denosumab, bisphosphonates, and/or radiotherapy was permitted to alleviate symptoms due to bone metastasis. Treatment after PD was not specified.

End points

The primary end point was the best overall response rate [ORR; complete response (CR) and partial response (PR)]. The secondary end points comprised the clinical benefit rate [CBR; CR, PR, and stable disease (SD) for at least 24 weeks], progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and safety.

Immunohistochemical and gene alteration analyses

AR staining was carried out on the primary lesion, or in several cases, on recurrent or metastatic lesions. All primary samples were revised by operative tissue, an open biopsy, or a core needle biopsy. Tumor tissue sections (4-μm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded) were immunohistochemically assessed using an anti-AR antibody (clone AR441; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Heat-mediated antigen retrieval was conducted in 1 mmol/l EDTA solution (pH 8.0) for 30 min. A polymer-based detection system with diaminobenzidine was used to detect antigen–antibody reactions. An immunohistochemical assessment was carried out by a head and neck pathologist (TN), who also provided a positive control slide for each immunohistochemical assay. AR positivity was evaluated just like the estrogen and progesterone receptors in accordance with the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guidelines for the evaluation of breast cancer predictive factors [23]. If a minimum of 1% of tumor cell nuclei were immunoreactive, the tumor was considered positive for AR. All cases were also checked for their human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status and its complex downstream signaling pathway gene mutations, including PIK3CA (exons 9 and 20), AKT1 (exon 2), H-RAS (exons 1-2), K-RAS (exons 1-2), N-RAS (exons 1-2), and BRAF (exon 15) genes, as described in supplementary methods and supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Statistical analyses

The tumor response was assessed every 6 weeks after the start of treatment until PD, via investigator assessment of computed tomographic scans or magnetic resonance imaging, according to the RECIST version 1.1 criteria. A medical image interpretation specialist (HO) from another institution carried out the image diagnosis. The PFS was defined as the time from the first administration of study treatment until PD or death. The OS was defined as the time from the first administration of study treatment to death from any cause. Safety was graded in accordance with the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. Kaplan–Meier estimates were used for time-to-event end points. To better characterize the efficacy of CAB, we carried out additional analyses of the primary and secondary end points according to selected clinicopathological factors including age, gender, RM versus LA disease groups, first-line versus ≥second-line systemic treatment groups, with or without M1 disease, with or without visceral metastasis, and selected biomarkers including AR positivity, HER2 status, and its complex downstream signaling pathway gene mutations by using the logistic regression model and the Cox proportional hazards model. All statistical analyses were two-sided, and probability values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using the software programs, GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows v. 6.07 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and STATA v.14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient characteristics

Thirty-six eligible AR-positive SGC patients were enrolled between March 2012 and 2016. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1, and detailed characteristics are summarized in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. The median AR positivity was 85% (range: 30%–100%). Seven patients had received prior chemotherapy for RM disease. The median interval time from chemotherapy to the beginning of CAB was 27.1 weeks (range: 2–155 weeks). Twelve patients (33%) with bone metastases received denosumab as supportive care.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic; All patients, N = 36 | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | 67 (46–90) |

| <75 | 28 (78) |

| ≥75 | 8 (22) |

| Median follow-up length, months (range) | 15 (1.3–38) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 34 (94) |

| Female | 2 (6) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 30 (83) |

| 1 | 6 (17) |

| Primary tumor site | |

| Parotid gland | 27 (75) |

| Submandibular gland | 6 (17) |

| Minor salivary gland | 3 (8) |

| Histology | |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | 34 (94) |

| Adenocarcinoma, NOS | 2 (6) |

| AR positivity (%) | |

| <70 | 6 (17) |

| ≥70 | 30 (83) |

| HER2 statusa | |

| Positive | 4 (11) |

| Negative | 32 (89) |

| Disease status | |

| Locally advanced diseaseb | 3 (8) |

| Recurrent/metastatic disease | 33 (92) |

| Disease extent | |

| Loco-regional disease | 13 (36) |

| Distant metastasis | 23 (64) |

| Visceral metastasis | 15 (42) |

| Previously untreated | 8 (22) |

| Previous treated | 28 (78) |

| Surgery | 27 (75) |

| Radiation therapy | 23 (64) |

| Chemotherapy | 16 (44) |

| Prior (neo)adjuvant therapy | 5 (14) |

| Prior concomitant chemoradiotherapy | 11 (31) |

| Prior lines of chemotherapy for RM disease | |

| 0 | 26 (72) |

| ≥1 | 7 (14) |

HER2 status according to breast cancer ASCO/CAP guideline (supplementary Reference 1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Locally advanced disease was defined as that which met at least one of the following conditions in newly diagnosed patients: (i) primary lesion of T4b, (ii) cervical lymph node metastasis of N2c or N3 according to UICC/TNM, 7th edition, and (iii) cervical lymph node metastasis invading the carotid artery.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; AR, androgen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Treatment outcome

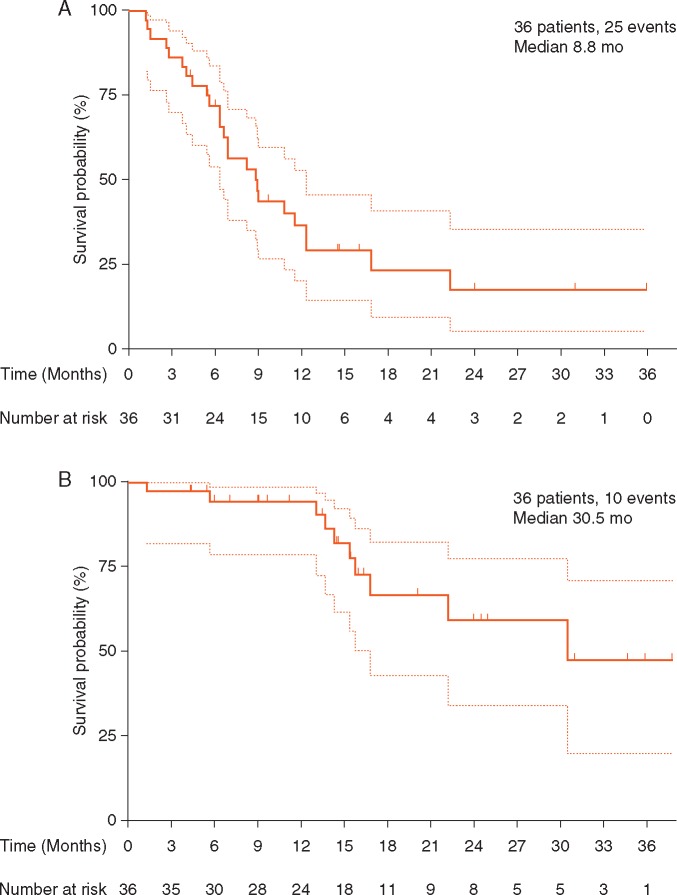

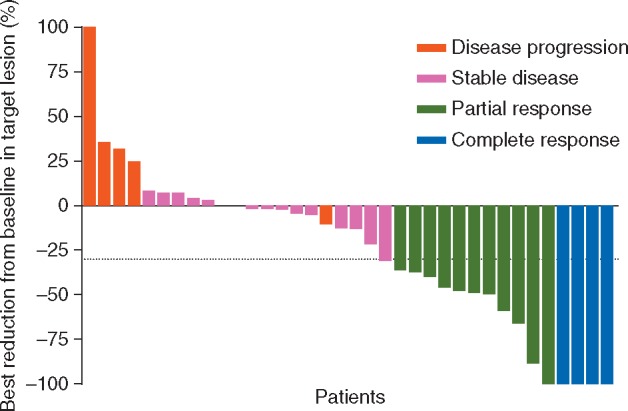

The treatment efficacy is summarized in Table 2. In all 36 patients, the ORR was 41.7% [n = 15, 95% confidence interval (CI); 25.5%–59.2%]; 12 patients showed SD for >24 weeks, and the CBR was 75.0% (n = 27, 95% CI, 57.8%–87.9%). The median PFS (mPFS) was 8.8 months (95% CI: 6.3–12.3 months), and the median OS (mOS) was 30.5 months (95% CI: 16.8–not reached) (Figure 1A and B). The best reduction from baseline was recorded in target lesions; 27 patients (75%) showed tumor shrinkage relative to baseline (Figure 2), and representative scans of patients with CRs or the PRs are shown in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Additional analyses between treatment outcomes and clinicopathological factors or biomarkers showed no statistically significant differences (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

Treatment efficacy (N = 36)

| Efficacy | Best overall response |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | 95% CI | |

| CR | 4 | 11.1 | 3.1–26.1 |

| PR | 11 | 30.6 | 16.3–48.1 |

| SD | 16 | 44.4 | 27.9–61.9 |

| PD | 5 | 13.9 | 4.7–29.5 |

| Confirmed objective response (CR + PR) | 15 | 41.7 | 25.5–59.2 |

| Clinical benefit (CR + PR + SD ≥ 24 weeks) | 27 | 75.0 | 57.8–87.9 |

| Median PFS, months | 8.8 | 6.3–12.3 | |

| Median OS, months | 30.5 | 16.8–NR | |

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of (A) progression-free survival (assessed by independent review) and (B) overall survival. The dotted bands on the Kaplan–Meier curves represent the 95% confidence bands.

Figure 2.

Best reduction from baseline in target lesions. Of the 36 patients, 27 patients (75%) showed tumor shrinkage relative to baseline.

Adverse events

The treatment toxicity is described in Table 3. Treatment-related grade 4/5 adverse events were not reported in any patient. Discontinuation of leuprorelin acetate or bicalutamide due to adverse events was reported in one patient each. Regarding the grade 3 liver dysfunction patients, one incident was due to bicalutamide and another was due to liver metastasis progression. The grade 3 creatinine increase patients had a history of renal failure, and creatinine increases were observed before CAB was initiated with no progression. Twenty subjects had grade 1 anemia, and nine had grade 1 hot flashes, but they did not require any treatment.

Table 3.

Adverse events (N)

| Adverse events | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 20 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Leukocytosis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Platelet count decreased | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypernatremia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperkalemia | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| AST/ALT increased | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Cr increased | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Hot flashes | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Malaise | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Penile pain | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Device related infection | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Upper respiratory infection | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary frequency | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gynecomastia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Laryngopharyngeal dysesthesia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Irregular menstruation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Erythema multiforme | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

AST/ALT, alanine transaminase/aspartate aminotransferase ratio; Cr, creatinine.

Discussion

This prospective phase II study evaluated the efficacy and toxicity of CAB for 36 AR-positive SGCs. The results showed that the ORR of CAB was 41.7%.

In this study, the histological diagnosis of most cases was SDC, but currently there is no standard systemic therapy for metastatic SDC [4, 6]. Recently, Nakano et al. reported the efficacy of chemotherapy in the largest number of SDCs to date [24]. Regarding the carboplatin–paclitaxel combination in 18 patients, the ORR was 39% (n = 7), and the mPFS was 6.5 months, an almost identical ORR or slightly shorter mPFS than those observed in the current CAB study.

Very few studies have investigated the efficacy of chemotherapy for SDC, but the regimens for “adenocarcinoma” and “adenocarcinoma, NOS” may be similarly effective in SDC based on the histological resemblance among the lesions. There are studies on cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide [25], paclitaxel alone [26], cisplatin–gemcitabine [27], and cisplatin–vinorelbine [28]. These studies included 7–17 patients and showed ORRs of 14%–25%, a median time to progression of 4–7 months, and an mOS of 12–21 months. We cannot conclude based on these previous findings that the efficacy of these cytotoxic chemotherapies is superior to that of CAB. On comparing the rates of adverse events, several grade 3/4 adverse events have been reported with these conventional chemotherapies including, neutropenia, leukocytopenia, febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, anorexia, weight gain, thrombosis/embolism, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and peripheral neurotoxicity. CAB therefore seems to be a less toxic systemic therapy than these chemotherapies.

Although the efficacy of hormone therapy for AR-positive SGC has been suggested in some case reports and retrospective analyses (Table 4) [13–20], to our knowledge, this is the first prospective study on CAB for SGC. Jaspers et al. reported 10 SDCs treated with bicalutamide [14], and Yajima et al. reported 8 SDCs treated with an LH-RH analogue [15]. In those studies, the ORRs were 20% and 25%, respectively. Locati et al. reported a better response rate in a retrospective study with CAB [19]. The authors administered bicalutamide and triptorelin to 17 patients with high-AR-expression SGCs. They found an ORR of 64.7%, mPFS of 11 months, and mOS of 44 months. Although the response rate of single hormone therapy for SGC was reported to be 20%–25%, Locati et al.’s and our data suggest that CAB may improve response rates by 15%–20% compared with ADT alone. However, in prostate cancer, three meta-analyses concluded that CAB reduced the risk of death by only 3%–5% compared with ADT alone [22]. SDC has more malignancy than prostate cancer that might contribute to larger benefit of CAB.

Table 4.

Reported cases of hormone therapy for androgen positive–salivary gland carcinoma

| Author (year) | Study design | N | Treatment | Efficacy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | PR | SD | PD | ||||

| Hulst (1994) [13] | Case report | 1 | LH-RH analogue | 1 | |||

| Jaspers (2011) [14] | Retrospective | 10 | 9: bicalutamide, 1: CAB | 2 | 3 | 5 | |

| Yajima (2012) [15] | Retrospective | 8 | LH-RH analogue | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Soper (2013) [16] | Case report | 1 | CAB + IMRT | 1 | |||

| Yamamoto (2014) [17] | Case report | 1 | Bicalutamide | 1 | |||

| Agbarya (2014) [18] | Case report | 1 | Bicalutamide + letrozole | 1 | |||

| Locati (2016) [19] | Retrospective | 17 | CAB | 3 | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| Boon (2016) [20] | Retrospective | 31 | ADTa | 4 | 10 | 17 | |

| Present study | Phase II | 36 | CAB | 4 | 11 | 16 | 5 |

Drug: unknown.

CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; LH-RH analogue, luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone analogue; CAB, combined androgen blockade; IMRT, intensity modulated radiation therapy; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy.

Little research has been carried out to predict the therapeutic effect in SGC. In our analyses of baseline patient factors potentially affecting ORR, CBR, PFS, or OS, no related indicators were found. Locati et al. investigated the AR expression as a predictive factor of the therapeutic effect of CAB [19], but failed to detect any other predictive factors, including EGFR, HER2, and HER3 protein expression, as well as genetic alterations in TP53, PIK3CA, HER2, PTEN, and AR. CAB for SGC seems less toxic than conventional chemotherapies but not as high as that for castration-naive prostate cancer, suggesting that elucidating the predictive factors for CAB will be beneficial in clinical practice.

Pathologically, most AR-positive SGCs are classified as SDCs [7–12]. In 2011 when we planned this study, a very low incidence of SDC was reported in the USA (0.018 per 100 000 per year) [3]. It was unclear whether we could secure the number of SDCs in this prospective study. Furthermore, because there were no published results of chemotherapy targeting a certain number of SDCs at that time, we could not set assumptions of null nor alternative hypotheses. We, therefore, started this study with a broad eligibility criteria (no limitations of age, prior chemotherapy, and including LA and RM patients) and without calculating an appropriate sample size. As a result, we could enroll the largest number of cases with this rare cancer.

We conclude that a low rate of toxicity is a major advantage of CAB with respect to patient acceptability and their quality of life. Our findings support the need for a prospective randomized clinical study on CAB versus chemotherapy or their combination, and the identification of biomarkers to predict the efficacy of CAB.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr Hiroaki Iobe and Ms Mayumi Yokotsuka, Tokyo Medical University, for their technical assistance.

Funding

JSPS Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) to YT (No. 15K10823) and TN (No. 17K08705); the Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) to DK (No. 17K18006).

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Tamaki T, Dong Y, Ohno Y. et al. The burden of rare cancer in Japan: application of the RARECARE definition. Cancer Epidemiol 2014; 38: 490–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. RARECARE. RARECARE Cancer List. Available at: http://www.rarecare.eu/rarecancers/rarecancers.asp (6 July 2017, date last accessed).

- 3. Boukheris H, Curtis RE, Land CE. et al. Incidence of carcinoma of the major salivary glands according to the WHO classification, 1992 to 2006: a population-based study in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 2899–2906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lewis AG, Tong T, Maghami E.. Diagnosis and management of malignant salivary gland tumors of the parotid gland. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2016; 49: 343–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Otsuka K, Imanishi Y, Tada Y. et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors for salivary duct carcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis of 141 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 2038–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alfieri S, Granata R, Bergamini C. et al. Systemic therapy in metastatic salivary gland carcinomas: a pathology-driven paradigm? Oral Oncol 2017; 66: 58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nagao T, Licitra L, Leoning T. et al. Salivary duct carcinoma In El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ (eds), WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours, 4th edition. IARC: Lyon, 2017; 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Locati LD, Perrone F, Losa M. et al. Treatment relevant target immunophenotyping of 139 salivary gland carcinomas (SGCs). Oral Oncol 2009; 45: 986–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mitani Y, Rao PH, Maity SN. et al. Alterations associated with androgen receptor gene activation in salivary duct carcinoma of both sexes: potential therapeutic ramifications. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 6570–6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dalin MG, Desrichard A, Katabi N. et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of salivary duct carcinoma reveals actionable targets and similarity to apocrine breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22: 4623–4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Masubuchi T, Tada Y, Maruya S. et al. Clinicopathological significance of androgen receptor, HER2, Ki-67 and EGFR expressions in salivary duct carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol 2015; 20: 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takase S, Kano S, Tada Y. et al. Biomarker immunoprofile in salivary duct carcinomas: clinicopathological and prognostic implications with evaluation of the revised classification. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 59023–59035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van der Hulst RW, van Krieken JH, van der Kwast TH. et al. Partial remission of parotid gland carcinoma after goserelin. Lancet 1994; 344: 817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaspers HC, Verbist BM, Schoffelen R. et al. Androgen receptor-positive salivary duct carcinoma: a disease entity with promising new treatment options. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: e473–e476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yajima Y, Fujii S, Kobayasi T. et al. Anti-androgen therapy for the patients with recurrent and/or metastatic salivary duct carcinoma expressing androgen receptors: a retrospective study. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: Abs 1796. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soper MS, Iganej S, Thompson LD.. Definitive treatment of androgen receptor-positive salivary duct carcinoma with androgen deprivation therapy and external beam radiotherapy. Head Neck 2014; 36: E4–E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamamoto N, Minami S, Fujii M.. Clinicopathologic study of salivary duct carcinoma and the efficacy of androgen deprivation therapy. Am J Otolaryngol 2014; 35: 731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Agbarya A, Billan S, Nasrallah H. et al. Hormone dependent metastatic salivary gland carcinoma: a case report. Springer Plus 2014; 3: 363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Locati LD, Perrone F, Cortelazzi B. et al. Clinical activity of androgen deprivation therapy in patients with metastatic/relapsed androgen receptor-positive salivary gland cancers. Head Neck 2016; 38: 724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boon E, Bel M, van der Graaf WT. et al. Salivary duct carcinoma: clinical outcomes and prognostic factors in 157 patients and results of androgen deprivation therapy in recurrent disease (n = 31)-study of the Dutch head and neck society (DHNS). J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(Suppl); Abstr 6016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prostate Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Maximum androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet 2000; 355: 1491–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gillessen S, Omlin A, Attard G. et al. Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer: recommendations of the St Gallen Advanced Prostate Cancer Consensus Conference (APCCC) 2015. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 1589–1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hammond ME, Hayes DF, Dowsett M. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College Of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 2784–2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nakano K, Sato Y, Sasaki T. et al. Combination chemotherapy of carboplatin and paclitaxel for advanced/metastatic salivary gland carcinoma patients: differences in responses by different pathological diagnoses. Acta Otolaryngol 2016; 136: 948–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Licitra L, Cavina R, Grandi C. et al. Cisplatin, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in advanced salivary gland carcinoma. A phase II trial of 22 patients. Ann Oncol 1996; 7: 640–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gilbert J, Li Y, Pinto HA. et al. Phase II trial of taxol in salivary gland malignancies (E1394): a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Head Neck 2006; 28: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laurie SA, Siu LL, Winquist E. et al. A phase 2 study of platinum and gemcitabine in patients with advanced salivary gland cancer: a trial of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group. Cancer 2010; 116: 362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Airoldi M, Garzaro M, Pedani F. et al. Cisplatin+vinorelbine treatment of recurrent or metastatic salivary gland malignancies (RMSGM): a final report on 60 cases. Am J Clin Oncol 2017; 40: 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.