Alcohol content, including branding, is highly prevalent in the MTV reality TV show ‘Geordie Shore’ Series 11. Current alcohol regulation is failing to protect young viewers from exposure to such content.

Abstract

Aim

To quantify the occurrence of alcohol content, including alcohol branding, in the popular primetime television UK Reality TV show ‘Geordie Shore’ Series 11.

Methods

A 1-min interval coding content analysis of alcohol content in the entire DVD Series 11 of ‘Geordie Shore’ (10 episodes). Occurrence of alcohol use, implied use, other alcohol reference/paraphernalia or branding was recorded.

Results

All categories of alcohol were present in all episodes. ‘Any alcohol’ content occurred in 78%, ‘actual alcohol use’ in 30%, ‘inferred alcohol use’ in 72%, and all ‘other’ alcohol references occurred in 59% of all coding intervals (ACIs), respectively. Brand appearances occurred in 23% of ACIs. The most frequently observed alcohol brand was Smirnoff which appeared in 43% of all brand appearances. Episodes categorized as suitable for viewing by adolescents below the legal drinking age of 18 years comprised of 61% of all brand appearances.

Conclusions

Alcohol content, including branding, is highly prevalent in the UK Reality TV show ‘Geordie Shore’ Series 11. Two-thirds of all alcohol branding occurred in episodes age-rated by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) as suitable for viewers aged 15 years. The organizations OfCom, Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) and the Portman Group should implement more effective policies to reduce adolescent exposure to on-screen drinking. The drinks industry should consider demanding the withdrawal of their brands from the show.

Short Summary

Alcohol content, including branding, is highly prevalent in the MTV reality TV show ‘Geordie Shore’ Series 11. Current alcohol regulation is failing to protect young viewers from exposure to such content.

INTRODUCTION

It is well-established that alcohol content occurs commonly in contemporary media such as film (Hanewinkel et al., 2007; Dal Cin et al., 2008; Lyons et al., 2011), TV (Blair et al., 2005; Lyons et al., 2013), music videos (DuRant et al., 1997; Cranwell et al., 2015, 2016a) and computer games (Cranwell et al., 2016b). Further, there is an established link between exposure to alcohol content in media, including paid for advertising, and the uptake of drinking in adolescents (Hanewinkel et al., 2007, 2012, 2014; Ross et al., 2014; Cranwell et al., 2016b). Alcohol advertising on television shows predicts an increased likelihood of binge and hazardous drinking in young people aged 15–20 years (Tanski et al., 2015), while a systematic review of prospective cohort studies found baseline non-drinkers were significantly more likely to start drinking after being exposed to alcohol advertisements (Smith and Foxcroft, 2009).

In the United Kingdom (UK) the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) regulate advertising in Broadcast media such as television (TV). The ASA proactively check the media for breaches of their alcohol advertising Codes. As stated in the ASA Code 19: ‘Advertisements for alcoholic drinks should not be targeted at people under 18 years of age and should not imply, condone or encourage immoderate, irresponsible or anti-social drinking.’ (ASA, 2015). The Portman Group, an organization representing the UK’s leading alcohol producers, also advocates regulating the promotion of alcohol and responsible marketing of alcohol products in the UK, for example, by not associating alcoholic drinks with drunkenness or binge drinking or branded alcoholic drinks having appeal to those under the UK legal drinking age of 18 years (Portman Group, 2015). Ofcom, the communications regulator in the UK, works under the provisions of the Communications Act 2003 and the Broadcasting Act 1996 to manage standards in programmes, sponsorship, product placement, fairness and privacy (Ofcom, 2016a) to ensure that television programme consumers are protected from harmful or offensive material (including both content and product placement) (Ofcom, 2016b).

Reality television chronicles un-scripted situations involving people in their daily lives or fabricated scenarios. Programmes often feature otherwise unknown casts and tend to focus on drama and personal conflict. ‘Geordie Shore’ (GS) is a UK primetime ‘hyper-reality’ TV series (similar to Made in Chelsea (MIC) and The Only Way is Essex (TOWIE)). It is based on the popular American reality show Jersey Shore (BBC, 2011). ‘Geordie’ is the regional dialect of people from the city Newcastle Upon Tyne in the UK, where the programme is primarily filmed. It chronicles the casts’ lives while living together in the GS house, typically dramatizing events and relationships (Wood, 2017). It is broadcast by the general entertainment channel media channel MTV in the UK and Ireland (MTV, 2017). In 2015, MTV UK reached an average 8.4 million UK viewers in the time period GS (Series 11) was originally aired (BARB (Broadcaster’s Audience Research Board), 2016).

MTV has been voted one of the Top 100 Best Global Brands for the last nine years (Syncforce, 2016) and was rated the number six top media brand by young people in the UK in 2014 (Statista, 2016). The channel focuses on younger generations, with a core audience of 12–34 year olds (Chozick, 2013). This audience reach of MTV affords significant marketing opportunities to companies seeking to promote their products to a young audience, but aside from a 2005 analysis of alcohol content in a Reality TV programme ‘The Osbourne's’, which recorded an average of 9.1 depictions of alcohol per episode (Blair et al., 2005), little is known about alcohol content in more contemporary programmes. In order to expand and add to the limited existing research on alcohol promotion in contemporary media this study has quantified the occurrence of alcohol content, including alcohol branding, in the popular primetime UK Reality TV show ‘Geordie Shore’ Series 11 (GS11), broadcast in 2015.

METHODS

Procedure

We purchased GS11, which at the time of data collection was the most recent series (broadcast between 20 October and 22 December 2015) on DVD. The series consists of 10 episodes, making it the longest series to date. Each episode was watched and coded for the presence or absence of alcohol content using established semi-quantitative interval media coding methods (Lyons et al., 2011; Cranwell et al., 2015) (see Online Supplementary Material for the detailed coding protocol). The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), which age-classifies films, videos and DVDs, rated six of the episodes as suitable for viewing by those aged 15 years or over, and 4 episodes suitable for those aged 18 years or over.

Audio–visual content of each episode using 1-min intervals was coded in the following categories: actual use, implied use without actual use, paraphernalia without actual or implied use, and brand appearance (real or fictitious), and any alcohol content (any of the above). The different types of alcohol and branding occurring in each coding interval were also recorded.

For each 1-min interval where actual alcohol use was present, four other categories were also coded:

Social context: alone, with other alcohol users, in the presence of a child or with other non-alcohol users.

Drunkenness: drinking but not obviously drunk, or obviously drunk.

Age: apparently under the age of 18, or apparently over the age of 18.

Gender: male, female, mixed drinking scene or drinker unidentified/unknown (e.g. non-human/silhouette).

Authors EL carried out the coding and JC checked samples of the coding at several points during data collection. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved. Repeated appearances in the same category during any single 1-min interval were coded as a single event, and appearances in different categories as separate events, with the exception of brands, for which different brands were counted as separate events. Where different categories of appearance of alcohol occurred simultaneously (e.g. actual and implied use of alcohol) the episode was coded under the higher of the categories as ranked above. Any partial intervals at the end of a video were counted as a full 1-min interval.

Data analysis

Data were recorded and descriptive statistics generated using Microsoft Excel 2010. Data were analysed using Stata MP 13.1 for Windows (StataCorp LP, Texas, US). Where required t-tests were performed and P values < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

RESULTS

The series included a total run time of 425 min and 54 s (each episode ranged from 42 min and 13 s to 42 min and 50 s). There were 430 1-min coding intervals in total, comprising 43 intervals per episode. Using the BBFC film rating categories episodes 1, 2, 3, 8, 9 and 10 were age-rated certificate 15 years and episodes 4, 5, 6 and 7 were age-rated certificate 18 years. Alcohol content in all four content subcategories was present in at least one 1-min interval in each of the ten episodes.

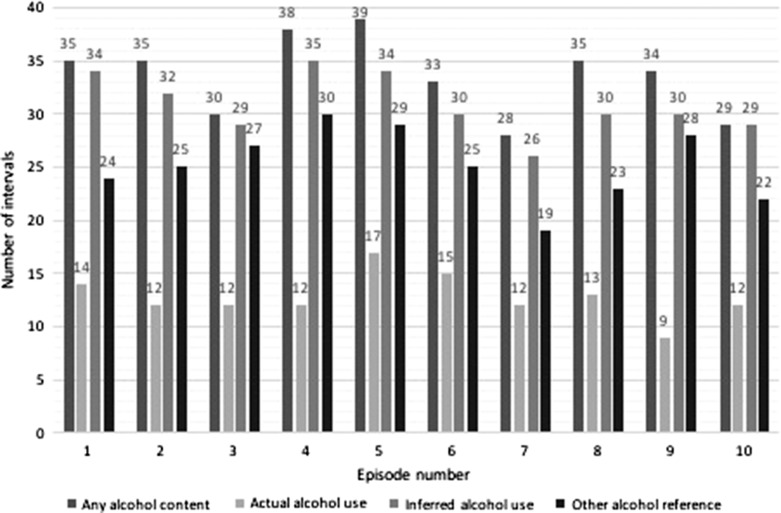

Any alcohol content was present in 336 intervals (78% of all intervals), and between 28 and 39 intervals per episode. Any alcohol appeared on average every 1.3 intervals, ranging from every 1.1 intervals in episode 5 to every 1.5 intervals in episode 7. The number of intervals containing any alcohol content by coded category and alcoholic branding can be seen in Fig. 1. None of the episodes coded included any alcohol-related disclaimers or warnings shown at the beginning of the episode.

Fig. 1.

Total number of intervals per episode containing any alcohol content, actual alcohol use, inferred alcohol use and other alcohol reference.

Actual alcohol use

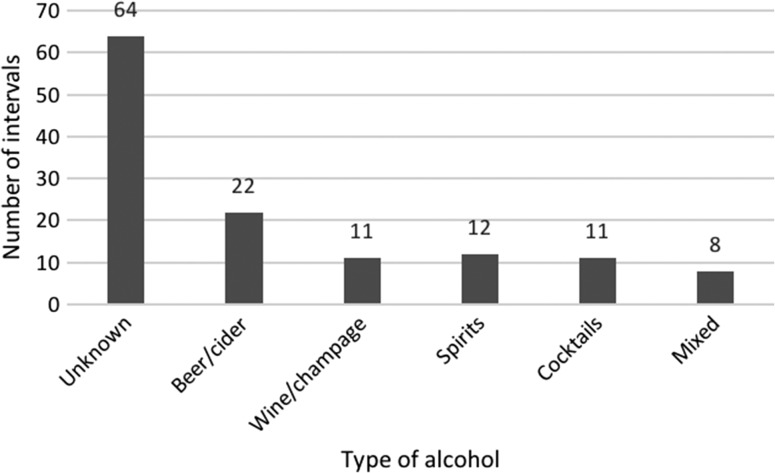

Actual alcohol use occurred in 128 (30%) intervals (Fig. 1) and between 9 (in episode 9) and 17 intervals (in episode 5) per episode. In 50% of episodes of actual alcohol use we were unable to identify the type of drink consumed, but in 17% the drink was beer or cider (17%), spirits (9%), wine or champagne and cocktails (both 9%). In 6% of episodes more than one type of drink was consumed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Total number of intervals by alcoholic drink type.

No alcohol consumption occurred in the presence of a child. Alcohol was consumed alone in 15% of episodes; with other, non-alcohol users in 4%; and with other alcohol users in 81%. Alcohol consumers were drinking and obviously drunk in 35% of intervals. All alcohol drinkers appeared to be over the age of 18 years. Male and female drinking in the same 1-min interval occurred in 45% of intervals with alcohol consumption; either together in the same scene or separately within the interval. Male-only drinking accounted for 27% and female-only drinking for 29% of actual use intervals.

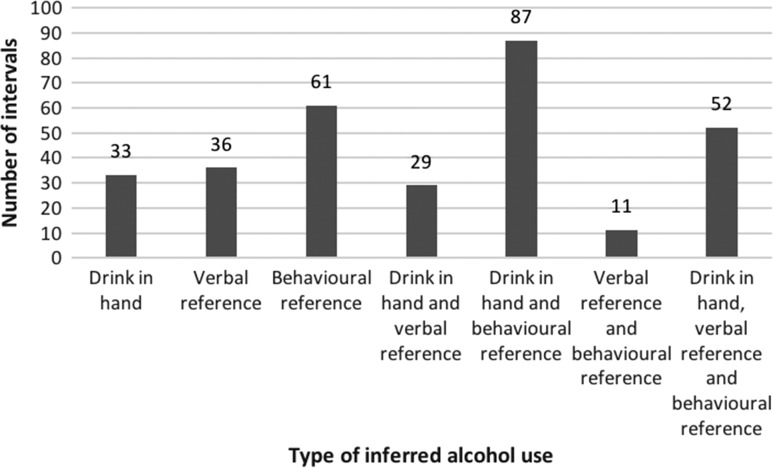

Inferred alcohol use

Inferred alcohol use occurred in 309 intervals (72% of all intervals) (Fig. 1), and ranged from 26 (episode 7) to 35 intervals (episode 4) per episode. Drunken behaviour and a verbal reference to alcohol occurred in 11 intervals (4% of inferred). These results are shown in Fig. 3. Of the 309 intervals containing inferred alcohol use, 201 involved a person holding an alcoholic drink, 128 include a verbal reference to alcohol and 211 include drunken behaviour.

Fig. 3.

The number of total intervals containing each (and multiple) categories of inferred alcohol use.

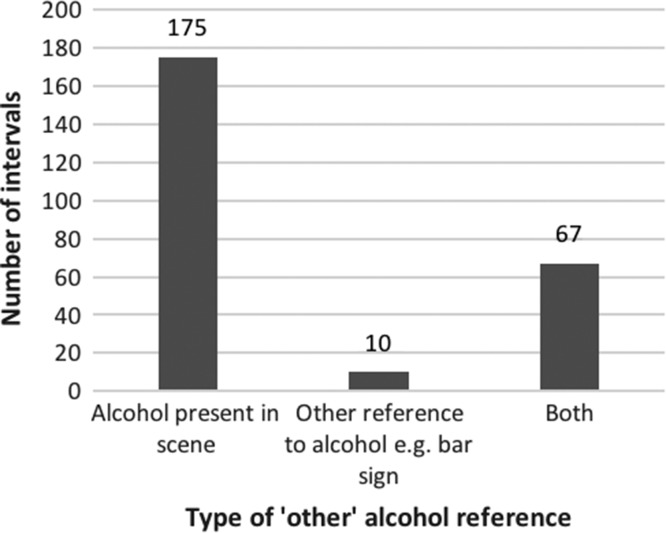

‘Other’ alcohol reference

Other alcohol references occurred in 252 intervals (59% of total) intervals (Fig. 1), and in between 19 (episode 7) and 30 intervals (episode 4) per episode. Other alcohol references comprised bar or club signs in 242 intervals, and usually occurred in conjunction with other alcohol appearances present in the scene (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The number of total intervals containing each category of other alcohol reference.

Alcohol branding

In total, 35 alcohol brands appeared at least once within the series. The number of different brands ranged from 3 (episode 6) to 23 (episode 7) per episode. The 23 brands present in episode 7 appeared a total of 25 times. The average number of brands per episode was 7.7. Of these brands, 10 were coded as beer/cider, one as wine/champagne and 24 as spirits (Table 1). The brands coded as spirits are divided into subcategories: vodka, rum, gin, whiskey, tequila and fruit liqueurs.

Table 1.

Alcohol brands categorized by alcohol type

| Spirits | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beer | Cider | Champagne | Vodka | Rum | Gin | Whiskey | Tequila | Fruit Liqueur |

|

|

Moët |

|

|

|

|

Jose Cuervo |

|

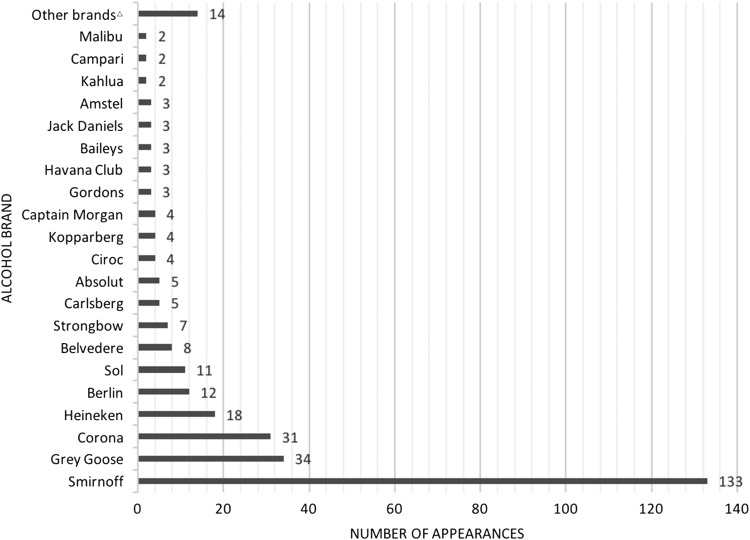

The mean number of alcoholic brand appearances per episode was 31, and ranged from 12 (episode 8) to 52 (episodes 3 and 5). Brand appearances occurred a total of 311 times, in 98 1-min intervals (23% of total). Of the 35 brands that appeared, Smirnoff was observed the most frequently (133 appearances, 43% of all brand appearances, Fig. 5). Five brands appeared three times each; Gordons, Havana Club, Baileys, Jack Daniels and Amstel. Three brands appeared twice each; Kahlua, Campari and Malibu. All other 14 brands appeared only once across the series.

Fig. 5.

Total number of appearances of each alcohol brand (n = 10 episodes). A further 14 brands had 1 appearance across the series.

The episodes with the highest intensity of a specific brand appearance are episodes 3 and 5, in which Smirnoff appeared 30 and 32 times, respectively. These appearances were in bar/club scenes where a Smirnoff bottle was situated on a table, featured as a wall decoration, or was held in someone’s hand. No brand was present in every episode, but Smirnoff appeared in all except episode 9 and Corona in all except episode 6. Alcohol branding was most frequently seen in bar/club scenes, but branding also appeared in the villa and boat used by the cast.

Brand appearances in relation to BBFC age rating

Episodes categorized as suitable for viewing by adolescents ≥15 years of age included 61% of all brand appearances. When comparing BBFC ratings of episodes (15 or 18) there was no statistical significance of the number of brand appearances present per episode (P = 0.92, CI = −21.9 to 23.9, mean difference = 1). The mean number of brand appearances in episodes age-rated 15 years was 31.5 per episode and in episodes age-rated 18 years was 30.5 per episode.

When comparing BBFC ratings of episodes (aged suitable for 15 or 18 years or over), there was no statistical significance in the number of different alcoholic brands present per episode (P = 0.19, 95% CI: −13.3 to 3.1, mean difference = −5.1). The mean number of brands present in episodes rated 15 years or over was 5.7 per episode and in episodes rated 18 years or over was 10.8 per episode. See Table 2 for alcohol brands categorized by alcohol type.

Table 2.

Alcohol brands and appearances per episode, according to BBFC rating

| Episode number | Number of different alcohol brands | Total number of alcohol brand appearances | BBFC age rating |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 42 | 15 |

| 2 | 7 | 37 | 15 |

| 3 | 6 | 52 | 15 |

| 4 | 6 | 31 | 18 |

| 5 | 11 | 52 | 18 |

| 6 | 3 | 14 | 18 |

| 7 | 23 | 25 | 18 |

| 8 | 4 | 12 | 15 |

| 9 | 4 | 18 | 15 |

| 10 | 7 | 28 | 15 |

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study demonstrate that the occurrence of alcohol content (verbal and imagery) and alcohol brand appearances is highly prevalent in ‘Geordie Shore: The Complete Eleventh Series’ (GS11). Any form of alcohol content (verbal or imagery) and actual alcohol use occurred in 78 and 30% of all coding intervals (ACIs), respectively. Alcoholic branding occurred in 23% of ACIs and, on average, once every 1.4 min. Further, more than half of all coded intervals contained inferred alcohol use and other reference to alcohol. The study also found that alcohol content and alcohol brand appearances occurred in all episodes of the series deemed suitable for viewing by young people below the age of 18 years. The legal drinking age in the UK is 18 years. This is an important finding because the drinks industry should be adhering to its own self-regulatory codes of practice which aim to prevent exposure of their products to an underage audience. However, the regulation of alcohol advertising in the UK has already been criticized for systematically failing by producers and agencies exploiting the ambiguities in the codes (Hastings et al., 2010). Similarly, our previous research found alcohol, including branding, to be the prevalent in contemporary music videos (which many UK adolescents are exposed to) with violations of both ASA, Portman Group and the drinks industry codes of conduct breached and drinking to excess was positively promoted through behavioural and verbal messages (Cranwell et al., 2016a, 2017). Our findings are consistent with these.

Our findings are also consistent with earlier studies reporting high levels of alcohol content in television programmes (Russell and Russell, 2009; Lyons et al., 2013), but is the first for over a decade to investigate the increasingly popular reality TV format. The young target audience, the wide reach of the MTV entertainment channel, and the popularity of GS11, means it is inevitable that adolescent viewers have been exposed to branded and unbranded alcohol imagery and on-screen drinking to excess, with related drunk and disorderly behaviour and sexual encounters. From a theoretical perspective adolescent exposure to this may influence and encourage young people to emulate this behaviour (Bryant and Oliver, 2009).

The overwhelming prevalence of Smirnoff, Corona and Grey Goose brand appearances, suggests an association with the brands and MTVs GS11 series. The Smirnoff brand is known to have a connection to MTV; in 2010 Smirnoff teamed up with MTV to showcase ‘The Smirnoff Nightlife Exchange Project’ (MTV, 2010), in 2012, pictureDRIFT worked with MTV to create a promotional video for MTVs summer sponsorship with Smirnoff Ice (Drift, 2013) and at the 2016 MTV Europe Music Awards, Smirnoff was a regional sponsor (BellaNaija, 2016). Smirnoff has multiple sponsorship deals, including 26 music festivals annually and Formula One racing (Interbrand, 2017) to help gain global audiences and engage consumers. Smirnoff itself accounted for 43% of all brand appearances in this study, comprising a significant amount of screen time.

Most alcoholic drink manufacturers adopt voluntary codes of practice regarding advertising of their products. Anheuser-Busch InBev, the leading global brewer, produces and sells over 200 beer brands globally (AB InBev, 2015). It owns two brands that appeared in this study; Corona and Budweiser. They have a voluntary marketing code that states ‘we are dedicated to promoting smart consumption and reducing the harmful use of alcohol’ (AB InBev, 2016) The code does not apply to television programmes that use their products without express permission to do so, which may have occurred in GS11. Drinks distributer Diageo is the global leader in alcohol beverages (Diageo, 2017). It owns five alcohol brands recorded in the data: Smirnoff, Captain Morgan, Baileys, Tanqueray and Cîroc. Diageo state that marketing will only be placed ‘where 71.6% or more of the audience are expected to be older than the legal purchasing age’ (Diageo, 2016). Clearly this is not guaranteed in GS11. Heineken UK and Bacardi Limited, the owners of Grey Goose, make similar claims in their corporate responsibility policies (Grey Goose, 2015; Heineken, 2015).

AB InBev, Carlsberg UK, Heineken UK and Diageo Great Britain all have products appearing in GS11 but are all signatories of the Portman Group. It is unclear whether the drinks manufacturers have paid for brand advertising in GS11, in which case several codes of practice have been clearly violated, or if this is a form of de facto advertising where brands are unofficially advertised without the alcohol producer’s knowledge, in which case it is surprising that the companies have not objected and demanded withdrawal of their products.

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that compared to other media as previously mention (e.g. music videos (45%), video games (44%) and television (40%)), there is a very high level of alcohol content and brand-specific alcohol imagery in the reality TV show Geordie Shore (78%), Series 11. Therefore, enforcing new policy measures to help protect adolescents from alcohol imagery in the media is essential. Given that 60% of GS11 episodes were awarded by the BBFC and age rating of 15 years, it appears that the existing age classification policy is not protecting young people from alcohol imagery and its potentially harmful effects. The BBFC should award reality television programmes, which include excessive alcohol content and which promote excessive drinking and/or brand placement, an age rating of 18+ years. The alcohol industry clearly needs to do more and should demand removal of their brands in shows that promote irresponsible drinking, if it is not paid for product placement. If paid for then this is a clear indication that the ASA, Portman Group, and industry codes of practice/advertising are clearly not protecting young people in the UK from exposure to on-screen irresponsible drinking. Moreover, they are not helping to prevent alcohol misuse and certainly not working towards fostering a balanced understanding of alcohol-related issues.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary data are available at Alcohol And Alcoholism online.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed to the design of this research study. E.L. conducted the analysis. J.C. produced the first draft of the article, and all authors contributed to subsequent revisions and preparation of the final report. All authors read and approved the final article.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING

This work was supported by the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, with core funding from the British Heart Foundation; Cancer Research UK; Economic and Social Research Council; Medical Research Council; and the Department of Health under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration [Grant number MR/K023195/1]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- AB InBev (2015) Annual Report [Online]. http://annualreport.ab-inbev.com/ (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- AB InBev (2016) Responsible Marketing and Communications Code 2.0 [Online]. http://www.ab-inbev.com/content/dam/universaltemplate/ab-inbev/sustainability/AB (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- ASA (2015) Alcohol Advertising (19 Alcohol, BCAP Code) [Online]. https://www.asa.org.uk/type/broadcast/code_section/19.html (5 December 2017, date last accessed).

- BARB (Broadcaster’s Audience Research Board) (2016) Quarterly Reach of MTV in the United Kingdom (UK) From 1st Quarter 2012 to 2nd Quarter 2016 (in 1,000 Viewers) [Online]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/290924/mtv-viewers-reached-quarterly-uk/ (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- BBC (2011) Jersey Shore v Geordie Shore [Online]. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-11140142 (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- BellaNaija (2016) The Weeknd to Perform Smash Single ‘Starboy’ at 2016 MTV EMAs This Weekend! Joins Bruno Mars, Green Day, OneRepublic & More Performers [Online]. https://www.bellanaija.com/2016/11/the-weeknd-to-perform-smash-single-starboy-at-2016-mtv-emas-this-weekend-joins-bruno-mars-green-day-onerepublic-more-performers/ (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Blair NA, Yue SK, Singh R, et al. (2005) Depictions of substance use in reality television: a content analysis of The Osbournes. Br Med J 331:1517–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant J, Oliver MB (2009) Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research.

- Chozick A. (2013) Longing to stay wanted, MTV turns its attention to younger viewers. The New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/18/business/media/longing-to-stay-wanted-mtv-turns-its-attention-to-younger-viewers.html?mcubz=0 (4 September 2017, date last accessed); Archived at http://www.webcitation.org/6tE156Tew (4 September 2017, date last accessed).

- Cranwell J, Britton J, Bains M (2017) ‘F* ck It! Let’s Get to Drinking—Poison our Livers!’: a Thematic Analysis of Alcohol Content in Contemporary YouTube MusicVideos. Int J Behav Med 24:66–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell J, Murray R, Lewis S, et al. (2015) Adolescents’ exposure to tobacco and alcohol content in YouTube music videos. Addiction 110:703–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell J, Opazo-Breton M, Britton J (2016. a) Adult and adolescent exposure to tobacco and alcohol content in contemporary YouTube music videos in Great Britain: a population estimate. J Epidemiol Community Health 70:488–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell J, Whittamore K, Britton J, et al. (2016. b) Alcohol and tobacco content in UK video games and their association with alcohol and tobacco use among young people. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 19:426–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Worth KA, Dalton MA, et al. (2008) Youth exposure to alcohol use and brand appearances in popular contemporary movies. Addiction 103:1925–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diageo (2016) Diagio Marketing Code (Rule 3f) [Online]. https://www.drinkiq.com/PR1102/media/19297/dmc_us_2016.pdf (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Diageo (2017) About us [Online]. https://www.diageo.com/en/our-business/who-we-are/ (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Drift P. (2013) MTV Summer Smirnoff Ice [Online]. http://www.mtv.co.uk/smirnoff-nightlife-exchange/news/smirnoff-nightlife-exchange (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- DuRant RH, Rome ES, Rich M, et al. (1997) Tobacco and alcohol use behaviors portrayed in music videos: a content analysis. Am J Public Health 87:1131–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey Goose (2015) Corporate Social Responsibility Policy [Online]. https://www.greygoose.com/uk/en/global-content/social-responsibility.html (4 September 2017, date last accessed).

- Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD, Hunt K, et al. (2014) Portrayal of alcohol consumption in movies and drinking initiation in low-risk adolescents. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD, Poelen EA, et al. (2012) Alcohol consumption in movies and adolescent binge drinking in 6 European countries. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Tanski SE, Sargent JD (2007) Exposure to alcohol use in motion pictures and teen drinking in Germany. Int J Epidemiol 36:1068–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings G, Brooks O, Stead M, et al. (2010) Failure of self regulation of UK alcohol advertising. Br Med J 340:b5650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heineken (2015) Corporate Responsibility [Online]. https://www.heineken.co.uk/corporate-responsibility (4 January 2017, date last accessed).

- Interbrand (2017) Smirnoff [Online]. http://interbrand.com/best-brands/best-global-brands/2015/ranking/smirnoff/ (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Lyons A, McNeill A, Britton J (2013) Alcohol imagery on popularly viewed television in the UK. J Public Health (Bangkok) 36:426–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, McNeill A, Gilmore I, et al. (2011) Alcohol imagery and branding, and age classification of films popular in the UK. Int J Epidemiol 40:1411–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MTV (2010) Smirnoff Nightlife Exchange [Online]. http://www.mtv.co.uk/smirnoff-nightlife-exchange/news/smirnoff-nightlife-exchange (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- MTV (2017) Geordie Shore [Online]. http://www.mtv.co.uk/geordie-shore (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Ofcom (2016. a) The Ofcom Broadcasting Code [Online]. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/about-ofcom/what-is-ofcom (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Ofcom (2016. b) What is Ofcom? [Online]. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/about-ofcom/what-is-ofcom (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Portman Group (2015) Lead, Regulate, Challenge [Online]. http://www.portmangroup.org.uk/ (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Ross CS, Maple E, Siegel M, et al. (2014) The relationship between brand‐specific alcohol advertising on television and brand‐specific consumption among underage youth. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38:2234–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell CA, Russell DW (2009) Alcohol messages in prime‐time television series. J Consum Aff 43:108–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Foxcroft DR (2009) The effect of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behaviour in young people: systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health 9:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista (2016) TV Channels That Generated the Greatest Volume of Tweets per Program in the UK From June 2012 to May 2013 [Online]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/314466/favorite-media-brands-of-young-people-uk (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Syncforce (2016) Rankings per Brand [Online]. http://www.rankingthebrands.com/Brand-detail.aspx?brandID=362 (16 August 2017, date last accessed).

- Tanski SE, McClure AC, Li Z, et al. (2015) Cued recall of alcohol advertising on television and underage drinking behavior. JAMA Pediatr 169:264–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood H. (2017) The politics of hyperbole on Geordie Shore: class, gender, youth and excess. Eur J Cult Stud 20:39–55. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.