Abstract

Purpose of Review

The intrarenal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAS) is an independent paracrine hormonal system with an increasingly prominent role in hypertension and renal disease. Two enzyme components of this system are angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and more recently discovered ACE2. The purpose of this review is to describe recent discoveries regarding the roles of intrarenal ACE and ACE2 and their interaction.

Recent Findings

Renal tubular ACE contributes to salt-sensitive hypertension. Additionally, the relative expression and activity of intrarenal ACE and ACE2 are central to promoting or inhibiting different renal pathologies including renovascular hypertension, diabetic nephropathy, and renal fibrosis.

Summary

Renal ACE and ACE2 represent two opposing axes within the intrarenal RAS system whose interaction determines the progression of several common disease processes. While this relationship remains complex and incompletely understood, further investigations hold the potential for creating novel approaches to treating hypertension and kidney disease.

Keywords: ACE, CE2, RAS, Hypertension, Kidney

Introduction

The local intrarenal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAS) functions as a paracrine hormonal system, independent from the systemic RAS. For one, all elements of the classical RAS are present and expressed in the kidney. In the kidney, renin is produced not only by the juxtaglomerular apparatus but also by principle cells of the connecting tubules and collecting ducts [1, 2•]. While there is some evidence to suggest that much of renal angiotensinogen (Agt) is produced systemically by the liver, Agt is also generated by the proximal tubule of the nephron [3]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme I (ACE), the enzyme responsible for converting angiotensin I (Ang I) to angiotensin II (Ang II), is similarly present throughout the kidney [4]. Additionally, intrarenal levels of Ang II are 1000-fold higher than its circulating levels in plasma [5, 6•, 7], implying that the majority of intrarenal Ang II is actually generated from within the kidney as a paracrine hormone [8]. A number of studies have further demonstrated the independent effects of the local renal RAS. Transgenic mice that overexpress Agt in the proximal tubule develop marked hypertension [9], and renal cross-transplantation studies have shown that Ang II inducible hypertension occurs only in animals with intact renal angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1R) [6•, 10, 11•].

More recently, several new components of the RAS have been discovered, including the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and the corresponding ACE2/Ang(1–7)/Mas axis, which are also present in the kidney [6•]. These newer RAS pathways have differing and often counterregulatory functions to the classic RAS system. The regulation and respective roles of these different elements of the renal RAS therefore remains an area of ongoing investigation. The focus of this review is to provide an overview of recent advances in understanding the roles of ACE and ACE2 in various pathologic processes in the kidney including what is known regarding the relative interaction of intrarenal ACE and ACE2 in renal pathophysiology.

ACE and ACE 2

The central function of ACE, both systemically and in the kidney, is the conversion of Ang I to Ang II. ACE is encoded by a gene located on chromosome 17q23 [12]. Although traditionally the pulmonary epithelium has been considered the main source of ACE, local intrarenal ACE production is quite abundant in the human kidney, with at least five times more ACE there than what has been found in the human lung [8, 13]. The highest concentrations of renal ACE occur in the brush border of the proximal tubule but ACE expression has also been reported in glomerular endothelium, mesangial cells, podocytes, and distal nephron [4, 11•, 13, 14, 15••, 16]. Intrarenal ACE expression is increased in several models of renal injury and hypertension including Ang II-induced hypertension, Goldblatt hypertension, and diabetic nephropathy, suggesting that ACE plays a critical role in renal injury and hypertension [17, 18].

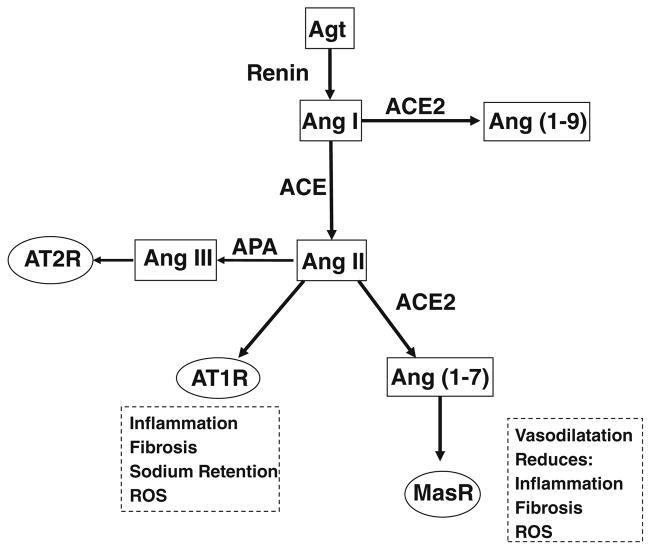

The ACE2 enzyme is a monocarboxypeptidase that was first reported in 2000 and consists of a signal peptide, potential transmembrane domain, and potential metalloproteinase zinc-binding site [19]. ACE2 generally counteracts many of the known functions of the conventional ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis. It degrades Ang II into the vasodilator and anti-proliferative Ang 1–7 and Ang I into the inactive Ang 1–9. Ang 1–7 in turn exerts anti-oxidant, anti-fibrotic, and anti-inflammatory properties through its receptor, known as Mas (MasR) [20, 21] (Fig. 1). ACE2 protein expression has been noted in the circulation as well as various tissues, including kidney, heart, liver, lung, and neurons [19, 22–25]. In the kidney specifically, ACE2 is highly expressed in tubular and glomerular epithelium, vascular smooth muscle cells, the endothelium of interlobular arteries, and glomerular mesangial cells [23, 26]. Similar to ACE, expression of ACE2 is altered in many renal disease states such as diabetic nephropathy [27•, 28•], hypertensive renal disease [29•, 30], Alport syndrome [31, 32], and renal fibrosis [33•, 34•].

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the actions of intrarenal ACE and ACE2. ACE converts Ang I to Ang II which is the ligand for the AT1R and promotes pathologic processes including inflammation, fibrosis, and sodium retention. ACE2 converts Ang I to Ang(1–9) and Ang II to Ang(1–7) which is the ligand for the MasR and counteracts many of the actions of the AT1R

Hypertension

RAS plays a central role in the pathogenesis of hypertension, and one area of recent interest regarding ACE has been its role in salt-sensitive hypertension. Salt sensitivity is one of the leading mechanisms behind hypertension. Renal injury, such as from increased inflammation or oxidative stress, increases RAS activity and impairs sodium excretion [35]. This in turn increases intravascular volume and causes an overall increase in blood pressure [11•]. The mechanistic role of ACE in this process was recently illustrated in an elegant series of experiments using strains of mice with minimal or no renal ACE expression. These mice notably have normal circulating ACE and Ang II levels as well as normal renal development, allowing researchers to determine the independent effects of intrarenal ACE [36••, 37]. In response to Ang II infusion, renal ACE-deficient mice did not develop hypertension and failed to increase renal Ang II or reduce urinary sodium excretion as seen in wild-type mice [37]. This effect was explained through differences in renal sodium handling, with ACE-deficient mice showing decreased activity of NCC and NKCC2 in response to Ang II compared to wild type [37]. To further study the role of intrarenal ACE in salt sensitivity, this model was given the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NAME, an agent that activates renal RAS without increasing systemic RAS activity, followed by high-salt diet. L-NAME alone had previously been shown to cause hypertension in wild-type mice but not in renal ACE-deficient mice [38]. In the setting of L-NAME and high-salt diet, renal ACE-deficient mice did not develop salt-sensitive hypertension, failed to demonstrate an increase in renal RAS activity, and had an amplified natriuretic response to high salt when compared to wild-type mice. These effects also corresponded to a greater reduction in phosphorylation of the sodium chloride cotransporter and expression of α-ENaC than in wild-type controls [36••]. Notably, lack of renal ACE also allowed mice to maintain an elevated GFR in the face of high salt that was lost in wild-type mice treated with L-NAME [36••]. The precise intrarenal location of the ACE activity responsible for salt-sensitive hypertension was further investigated using a mouse lacking ACE only in the tubular epithelial brush border [15••]. This model was also resistant to L-NAME-induced salt sensitivity and did not increase renal Ang II while demonstrating increased natriuresis and similarly decreased renal sodium transporter activity compared to wild type. In contrast, a mouse model that expresses ACE only in renal tubular epithelium developed salt-sensitive hypertension with L-NAME exposure [15••]. Taken together, this series of experiments prove that renal epithelial ACE is a major player in generating salt-sensitive hypertension, independent of systemic RAS activity, by regulating changes in renal sodium transport.

With the discovery of newer RAS components including ACE2, an important area of ongoing research interest is directed toward the balance between ACE and ACE2 in hypertension. It has generally been understood that the ACE2/Ang(1–7)/Mas axis acts to counterregulate the vasoconstrictive and hypertensive activity of the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis. Recent studies showed that high-salt diet in spontaneously hypertensive rats decreased ACE2 expression while increasing the ACE/ACE2 ratio, glomerular hypertrophy, loss of the podocytes foot processes, and proteinuria [29•]. These effects were attenuated by low salt and normal salt diets which also decreased the ratio of renal ACE/ACE2 expression [29•]. While these findings imply that changes in ACE/ACE2 ratio may be responsible for hypertensive changes, this study unexpectedly found no difference in ACE or ACE2 activity during high salt intake despite an increase in ACE expression [29•]. In a different approach, continuous administration of losartan in spontaneously hypertensive rats decreased blood pressure and increased ACE2 expression, suggesting that increased ACE2/Mas activity could be responsible for reductions in blood pressure. Notably, though there was no increase in the renal ACE2 receptor Mas in this study [39]. Adding further uncertainty, another recent study showed that intrarenal alterations of the ACE2/Ang1–7 complex did not significantly modify the course of malignant hypertension in Cyp1a1-Ren-2 transgenic rats, which have abnormally increased activity of the ACE/Ang II/AT1 pathway [40]. Taken together, these studies not only generally support opposing roles for intrarenal ACE and ACE2 in hypertension but also make clear that further studies are needed to understand the specific interactions between these two axes in the kidney.

Another model that has been used for exploring temporal roles of intrarenal ACE and ACE2 in the development of hypertension has been the 2-kidney 1-clip (2K1C) rodent model of renovascular hypertension. In this model, ACE levels are increased in the clipped kidney. Early in the course of 2K1C hypertension, renal ACE levels are not changed while ACE2 levels decrease. However, at 5 weeks, ACE expression is increased while ACE2 remains suppressed [41•]. This study further revealed that AT1R was initially suppressed in the proximal tubule of the clipped kidney but then increased during the maintenance phase of hypertension [41•]. These data indicate that reductions in ACE2 may be important for initiating hypertension while ACE plays a central role in maintaining elevated blood pressure. At the same time, the simultaneous increase in ACE and AT1R despite known increases in Ang II may further work to sustain renovascular hypertension.

It is also worth noting that Collectrin, an ACE2 homolog that lacks the enzymatic activity of ACE2, is expressed in the proximal tubule and collecting duct and is downregulated in Ang II-induced hypertension via the AT1R [42••]. Collectrin knockout mice are hypertensive and have increased salt sensitivity as well as reduced renal blood flow and renal medullary neuronal nitric oxide synthase dimerization [42••, 43]. Furthermore, in the setting of high-salt diet, wild-type mice that received transplanted kidneys from collectrin knockout mice developed higher blood pressure than knockout mice given wild-type kidneys or wild type alone and these differences correspond to higher levels of the renal sodium-hydrogen antiporter 3 (NHE3) [42••]. Taken together, these results indicate that in addition to the evident roles for renal ACE/Ang II/AT1R and ACE2/Ang(1–7)/Mas in hypertension, modulations in other similar intrarenal RAS components are additional factors contributing to the increasingly complex picture of the intrarenal RAS and hypertension.

Diabetic Nephropathy

RAS is also known to play an important role in diabetic kidney disease and it is well established that ACE inhibition is protective against the development of diabetic nephropathy. Some reports suggested that different polymorphisms of the ACE gene affect renal as well as systemic ACE expression and confer varying degrees risk of diabetic nephropathy [12]. Further work is needed, however, to fully understand the implications of these ACE genetic variations.

Some previous studies have demonstrated that renal glomerular and tubular expression of ACE2 are significantly decreased in experimental and clinical diabetic nephropathy [44] while others have reported increased ACE2 expression in the renal cortex of non-obese mice with diabetes [45]. Nonetheless, subsequent investigation has established a protective role for ACE2 against diabetic nephropathy. ACE2 inhibition in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse model showed increased urine albumin to creatinine ratio as well as expansion of the glomerular matrix relative to mice with diabetes alone [46]. More recently, ACE2 knockout in diabetic mice was associated with increased blood pressure, mesangial matrix expansion, podocytes loss, and renal fibrosis including increased α-SMA accumulation and collagen deposition when compared to wild-type diabetic mice [47, 48••]. Importantly, the protective effects of ACE2 expression have also been found to be specific to the kidney. Enhancement of circulating ACE2 alone in streptozotocin diabetic mice failed to improve glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria, or kidney histology [49]. Meanwhile, enhancement of ACE2 expression in renal tubular epithelial cells reversed high glucose-induced increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and apoptosis. In contrast, increasing ACE2 expression in the renal proximal tubules of diabetic mice decreased fibrosis and albuminuria [28•, 30].

ACE2 can be measured in the urine and there is good evidence that its levels may serve as a marker for monitoring disease progression and metabolic state [22]. In the setting of hyperglycemia, an ACE2 ectodomain is cleaved by “a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17” (ADAM17) and PKC-δ in the apical membrane of the proximal tubule and shed in the urine [50, 51•]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that the urinary ACE2/Cr ratio positively correlated with metabolic parameters including fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, triglyceride, and total cholesterol [52]. Additionally, urinary ACE2 level is predictive of urinary nephrin level, a marker of podocyte health [53]. There is also some evidence to suggest that blocking renal shedding of ACE2 could be therapeutic. Studies giving paricalcitol to non-obese mice with type 1 diabetes demonstrated decreased ADAM17 expression and increased renal ACE2 expression compared to untreated diabetic mice [45]. These studies suggested that ACE2 levels may be increased by preventing its renal shedding. These findings raise the question as to whether urinary ACE2 could be a measure of disease progression as well as a marker of response to treatment.

Similar to hypertension, there is increasing evidence that the relative increase in renal activity of the classic ACE/Ang II/AT1R versus ACE2/Ang(1–7)/Mas pathway is key to the progression of diabetic nephropathy. The AT1R antagonist candesartan, a well-accepted therapy in diabetic nephropathy, has recently been shown to improve renal tubular damage and albuminuria, partially through upregulation of ACE2/AT2R/Mas axis activity in the kidney [27•]. Conversely, treatment of diabetic rats with calcitriol reduced renal ACE levels and increased renal ACE2 expression, thus decreasing the ACE/ACE2 ratio, and associated with a reduction in proteinuria [54•]. Interestingly, in this study, reductions in ACE were mediated by the p38MAPK pathway, while ACE2 was upregulated via the ERK signaling pathway [54•]. Systemic use of recombinant human ACE2 in diabetic mice similarly attenuated kidney injury while reducing blood pressure and decreasing NADPH oxidative activity [55]. In vitro investigations of this effect in high glucose or Ang II-treated renal mesangial cells demonstrated that the reduction in oxidative stress with ACE2 occured, at least in part, through a reduction in Ang II that was mediated by increasing its conversion to Ang1–7 [55]. Further support for the cross talk between renal ACE and ACE2 was demonstrated by the finding of increased renal ACE expression during ACE2 inhibition [46]. However, at least one recent study using the ACE2 knockout mouse found that while ACE2 deletion increased systemic ACE expression and worsened nephropathy, renal cortical ACE was in fact decreased [48••]. These findings emphasize the importance of the ongoing investigations into interactions of ACE and ACE2 in diabetic kidney disease.

Chronic Kidney Disease and Renal Fibrosis

While the ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis is known to contribute to chronic renal injury, the protective effects of ACE2/Ang(1–7)/Mas are becoming evident as well. ACE2 deficiency enhances kidney inflammation and renal fibrosis and exacerbates the progression of chronic kidney disease [56]. Conversely, administration of Ang(1–7) significantly reduced the inflammatory markers in the plasma and kidney, including IL-6, TNF-α, CRP, and MCP-1 in high-fat diet-fed mice, modulated renal lipid metabolism through the LDLr-SREBP2-SCAP pathway, and as a result, reduced renal damage induced by lipid [57•]. Similarly, rACE2 supplementation in ApoE KO mice reduced expression of IL-1beta, IL-6, IL-17A, TNF-alpha, TGF-beta and collagen I, and renal structural injury via modulation of the mTOR/ERK signaling pathway and renal Ang(1–7)/Ang II balance [33•, 56]. In a recent study, administration of the GLP-1 analog exendin-4, a renoprotective agent, in the setting of unilateral ureteral obstruction, reversed ACE upregulation and increased ACE2 expression while reducing renal fibrosis and expression of Ang II and profibrotic factors TGF-β/Smad3 [34•]. There was also a trend toward improved expression of the ACE2 product Ang(1–7) with exendin, but this did not reach statistical significance [34•]. These results nonetheless emphasize the importance of the relative activity of ACE and ACE2 in the progression of renal fibrosis.

Similar to findings in diabetes, there is also evidence that elevated urinary ACE2 levels may signal worsening kidney disease. Rats with subtotal nephrectomy not only had increased kidney cortical ACE and reduced cortical and medullary ACE2 activities but also showed increased urinary ACE2 levels which correlated positively with urinary protein excretion, and negatively with creatinine clearance [58]. In a similar manner, while circulating, ACE2 activity is significantly decreased in patients with stage 3–5 (CKD3–5) and on dialysis (CKD5D), urinary ACE2 is significantly higher in CKD3–5 patients and correlates with urine albumin/creatinine ratio [59, 60]. These data suggest that shedding of ACE2 in the urine may be a marker of decreased renal and systemic ACE2 activity and progression of chronic kidney disease.

Alport Syndrome

ACE2 may also represent a novel marker of Alport syndrome (AS)-associated kidney injury. In 7-week old type IV collagen α3 gene knockout (Col4A3−/−) mice, there was decreased expression and activity of renal ACE2 and the urinary excretion rate of ACE2 paralleled the decline in tissue expression [31]. Recombinant exogenous ACE2 treatment partially reversed these changes by decreasing expression of collagen I mRNA, TGF-β signaling, TNF-α-converting enzyme, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and macrophage infiltration, leading to attenuation of the progression of Alport syndrome-related nephropathy [61].

Conclusion

While RAS has long been identified as a major player in renal pathophysiology, our conception of the intrarenal RAS and its role continues to evolve. As newer components of RAS are discovered, this picture continues to grow in complexity. The interplay between intrarenal ACE and ACE2 is now clearly central to any understanding of how RAS promotes or prevents various pathologic processes involving the kidney. At the same time, the precise ways in which these two important members of the RAS interact and regulate one another is far from resolved. Better characterization of this relationship will likely have significant implications for our future detection and treatment of hypertension and kidney disease.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions All authors contributed to the manuscript writing. The authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest Drs. Culver, Li, and Siragy declare no conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Rohrwasser A, Morgan T, Dillon HF, Zhao L, Callaway CW, Hillas E, et al. Elements of a paracrine tubular renin-angiotensin system along the entire nephron. Hypertension. 1999;34:1265–74. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.6.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2•.Yang T, Xu C. Physiology and pathophysiology of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: an update. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:1040–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016070734. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016070734A recent review on the function and regulation of the intrarenal RAS in contrast with systemic RAS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsusaka T, Niimura F, Shimizu A, Pastan I, Saito A, Kobori H, et al. Liver angiotensinogen is the primary source of renal angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1181–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121159. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2011121159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casarini DE, Boim MA, Stella RC, Krieger-Azzolini MH, Krieger JE, Schor N. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme activity in tubular fluid along the rat nephron. Am J Phys. 1997;272:F405–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.272.3.F405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishiyama A, Seth DM, Navar LG. Renal interstitial fluid angiotensin I and angiotensin II concentrations during local angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2207–12. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000026610.48842.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Carey RM. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in hypertension. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22:204–10. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.11.004. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2014.11.004A review of recent advances in understanding of the intrarenal RAS as well as the role of newer RAS pathways in hypertension. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey RM, Siragy HM. Newly recognized components of the renin-angiotensin system: potential roles in cardiovascular and renal regulation. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:261–71. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0001. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2003-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdos EG, Skidgel RA. Structure and functions of human angiotensin I converting enzyme (kininase II) Biochem Soc Trans. 1985;13:42–4. doi: 10.1042/bst0130042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang SL, Liu F, Hsieh TJ, Brezniceanu ML, et al. RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1016–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Herrera MJ, Ruiz P, Griffiths R, Kumar AP, et al. Angiotensin II causes hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through its receptors in the kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17985–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605545103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Giani JF, Shah KH, Khan Z, Bernstein EA, Shen XZ, McDonough AA, et al. The intrarenal generation of angiotensin II is required for experimental hypertension. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;21:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.01.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2015.01.002This study shows that mice lacking renal ACE fail to generate intrarenal Ang II or develop hypertension when treated with Ang II or L-NAME. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rahimi Z. The role of renin angiotensin aldosterone system genes in diabetic nephropathy. Can J Diabetes. 2016;40:178–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.08.016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernstein KE, Giani JF, Shen XZ, Gonzalez-Villalobos RA. Renal angiotensin-converting enzyme and blood pressure control. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:106–12. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000441047.13912.56. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mnh.0000441047.13912.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Billet S, Kim C, Satou R, Fuchs S, Bernstein KE, et al. Intrarenal angiotensin-converting enzyme induces hypertension in response to angiotensin I infusion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:449–59. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010060624. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2010060624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Giani JF, Eriguchi M, Bernstein EA, Katsumata M, Shen XZ, Li L, et al. Renal tubular angiotensin converting enzyme is responsible for nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced salt sensitivity. Kidney Int. 2017;91:856–67. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.007. This study uses a mouse model with no renal tubular ACE and another with ACE only in the renal tubular epithelium to demonstrate that renal tubular ACE is critical for development of salt sensitivity in response to L-NAME. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebau MC, Lang D, Bohm J, Endlich N, Bek MJ, Witherden I, et al. Functional expression of the renin-angiotensin system in human podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F710–9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00475.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Satou R, Ohashi N, Semprun-Prieto LC, Katsurada A, Kim C, et al. Intrarenal mouse renin-angiotensin system during ANG II-induced hypertension and ACE inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F150–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00477.2009. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00477.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vio CP, Jeanneret VA. Local induction of angiotensin-converting enzyme in the kidney as a mechanism of progressive renal diseases. Kidney Int Suppl. 2003;86:S57–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s86.11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, Godbout K, Gosselin M, Stagliano N, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ Res. 2000;87:E1–9. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Padda RS, Shi Y, Lo CS, Zhang SL, Chan JS. Angiotensin-(1–7): a novel peptide to treat hypertension and nephropathy in diabetes? J Diabetes Metab. 2015:6. doi: 10.4172/2155-6156.1000615. doi: https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6156.1000615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Shi Y, Lo CS, Padda R, Abdo S, Chenier I, Filep JG, et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) prevents systemic hypertension, attenuates oxidative stress and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and normalizes renal angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and Mas receptor expression in diabetic mice. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015;128:649–63. doi: 10.1042/CS20140329. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20140329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao F, Burns KD. Measurement of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity in biological fluid (ACE2) Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1527:101–15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6625-7_8. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6625-7_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lely AT, Hamming I, van Goor H, Navis GJ. Renal ACE2 expression in human kidney disease. J Pathol. 2004;204:587–93. doi: 10.1002/path.1670. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuba K, Imai Y, Rao S, Gao H, Guo F, Guan B, et al. A crucial role of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in SARS coronavirus-induced lung injury. Nat Med. 2005;11:875–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osterreicher CH, Taura K, De Minicis S, Seki E, Penz-Osterreicher M, Kodama Y, et al. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme 2 inhibits liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:929–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.23104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.23104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu CX, Hu Q, Wang Y, Zhang W, Ma ZY, Feng JB, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) 2 overexpression ameliorates glomerular injury in a rat model of diabetic nephropathy: a comparison with ACE inhibition. Mol Med. 2011;17:59–69. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00111. https://doi.org/10.2119/molmed.2010.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27•.Callera GE, Antunes TT, Correa JW, Moorman D, Gutsol A, He Y, et al. Differential renal effects of candesartan at high and ultra-high doses in diabetic mice-potential role of the ACE2/AT2R/Mas axis. Biosci Rep. 2016;36:e00398. doi: 10.1042/BSR20160344. This study demonstrates that the renoprotective effects of the Candesartan occur with upregulation of the ACE2/AT2R/Mas axis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28•.Huang YF, Zhang Y, Liu CX, Huang J, Ding GH. microRNA-125b contributes to high glucose-induced reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis in HK-2 renal tubular epithelial cells by targeting angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:4055–62. This in vitro study shows that blocking microRNA-125b mediated downregulation of ACE2 in renal tubular epithelial cells and prevents high glucose-mediated ROS production and apoptosis. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Berger RC, Vassallo PF, de Crajoinas RO, Oliveira ML, Martins FL, Nogueira BV, et al. Renal effects and underlying molecular mechanisms of long-term salt content diets in spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141288. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141288This study describes the effects of high- and low-salt diets on ACE/ACE2 ratio and associated renal injury. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan J, Lo CS, Shi Y, Chenier I, Zhang SL. Os 25-03 overexpression of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F prevents systemic hypertension and kidney injury and normalizes renal renin-angiotensin system genes expression in type 2 diabetic Db/db transgenic mice. J Hypertens. 2016;34(Suppl 1):e245. ISH 2016 Abstract Book. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.hjh.0000500552.89974.b8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bae EH, Konvalinka A, Fang F, Zhou X, Williams V, Maksimowski N, et al. Characterization of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in experimental Alport syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:1423–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.01.021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross MJ, Nangaku M. ACE2 as therapy for glomerular disease: the devil is in the detail. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1269–71. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Chen LJ, Xu YL, Song B, Yu HM, Oudit GY, Xu R, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 ameliorates renal fibrosis by blocking the activation of mTOR/ERK signaling in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Peptides. 2016;79:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2016.03.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2016.03.008This study demonstrates that recombinant ACE2 prevents Ang II-mediated fibrosis in ApoE knockout mice via upregulation Ang(1–7) and inhibition of mTOR/ERK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Le Y, Zheng Z, Xue J, Cheng M, Guan M, Xue Y. Effects of exendin-4 on the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system and interstitial fibrosis in unilateral ureteral obstruction mice: exendin-4 and unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2016;17:1470320316677918. doi: 10.1177/1470320316677918. This study demonstrates that exendin-4 reduces renal fibrosis in the setting of ureteral obstruction while increasing ACE2 and decreasing ACE expressions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Franco M, Johnson RJ. Impaired pressure natriuresis is associated with interstitial inflammation in salt-sensitive hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2013;22:37–44. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835b3d54. https://doi.org/10.1097/MNH.0b013e32835b3d54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36••.Giani JF, Bernstein KE, Janjulia T, Han J, Toblli JE, Shen XZ, et al. Salt sensitivity in response to renal injury requires renal angiotensin-converting enzyme. Hypertension. 2015;66:534–42. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05320. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05320This study demonstrates that mice lacking renal ACE fail to develop salt sensitivity following treatment with L-NAME due to reduced intrarenal Ang II production and alterations in renal sodium channel activity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Villalobos RA, Janjoulia T, Fletcher NK, Giani JF, Nguyen MT, Riquier-Brison AD, et al. The absence of intrarenal ACE protects against hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2011–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI65460. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI65460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giani JF, Janjulia T, Kamat N, Seth DM, Blackwell WL, Shah KH, et al. Renal angiotensin-converting enzyme is essential for the hypertension induced by nitric oxide synthesis inhibition. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:2752–63. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013091030. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2013091030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klimas J, Olvedy M, Ochodnicka-Mackovicova K, Kruzliak P, Cacanyiova S, Kristek F, et al. Perinatally administered losartan augments renal ACE2 expression but not cardiac or renal Mas receptor in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2015;19:1965–74. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12573. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.12573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huskova Z, Kopkan L, Cervenkova L, Dolezelova S, Vanourkova Z, Skaroupkova P, et al. Intrarenal alterations of the angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2/angiotensin 1-7 complex of the renin-angiotensin system do not alter the course of malignant hypertension in Cyp1a1-Ren-2 transgenic rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016;43:438–49. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12553. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1681.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Kim YG, Lee SH, Kim SY, Lee A, Moon JY, Jeong KH, et al. Sequential activation of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system in the progression of hypertensive nephropathy in Goldblatt rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311:F195–F206. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00001.2015. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00001.2015This study describes the temporal changes in ACE and ACE2 expression in the 2K1C model and hypothesizes their relative contribution to the generation and maintenance of hypertension. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42••.Chu PL, Gigliotti JC, Cechova S, Bodonyi-Kovacs G, Chan F, Ralph DL, et al. Renal collectrin protects against salt-sensitive hypertension and is downregulated by angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:1826–37. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016060675. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2016060675This study demonstrates through cross-transplantation of collectrin knockout kidneys into wild-type mice that collectrin protects against salt-sensitive hypertension via downregulation of the NHE3 sodium transporter. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cechova S, Zeng Q, Billaud M, Mutchler S, Rudy CK, Straub AC, et al. Loss of collectrin, an angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 homolog, uncouples endothelial nitric oxide synthase and causes hypertension and vascular dysfunction. Circulation. 2013;128:1770–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003301. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ye M, Wysocki J, William J, Soler MJ, Cokic I, Batlle D. Glomerular localization and expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and angiotensin-converting enzyme: implications for albuminuria in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3067–75. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soler MJ, Wysocki J, Ye M, Lloveras J, Kanwar Y, Batlle D. ACE2 inhibition worsens glomerular injury in association with increased ACE expression in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Kidney Int. 2007;72:614–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiota A, Yamamoto K, Ohishi M, Tatara Y, Ohnishi M, Maekawa Y, et al. Loss of ACE2 accelerates time-dependent glomerular and tubulointerstitial damage in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:298–307. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.231. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clotet S, Soler MJ, Rebull M, Gimeno J, Gurley SB, Pascual J, et al. Gonadectomy prevents the increase in blood pressure and glomerular injury in angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 knockout diabetic male mice. Effects on renin-angiotensin system. J Hypertens. 2016;34:1752–65. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001015. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48••.Wysocki J, Ye M, Khattab AM, Fogo A, Martin A, David NV, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 amplification limited to the circulation does not protect mice from development of diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1336–46. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.032. This study finds that increasing systemic ACE2 with recombinant ACE2 does not prevent diabetic changes in GFR, albuminuria, or glomerular histopathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao F, Zimpelmann J, Agaybi S, Gurley SB, Puente L, Burns KD. Characterization of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 ectodomain shedding from mouse proximal tubular cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085958. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0085958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xiao F, Zimpelmann J, Burger D, Kennedy C, Hebert RL, Burns KD. Protein kinase C-delta mediates shedding of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 from proximal tubular cells. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:146. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2016.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51•.Liang Y, Deng H, Bi S, Cui Z, AL, Zheng D, et al. Urinary angiotensin converting enzyme 2 increases in patients with type 2 diabetic mellitus. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2015;40:101–10. doi: 10.1159/000368486. https://doi.org/10.1159/000368486This study demonstrates a correlation between urinary ACE2 to creatinine ratio and various measures metabolic markers of disease including hemoglobin A1C, cholesterol, and blood glucose. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mariana CP, Ramona PA, Ioana BC, Diana M, Claudia RC, Stefan VD, et al. Urinary angiotensin converting enzyme 2 is strongly related to urinary nephrin in type 2 diabetes patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48:1491–7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-016-1334-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-016-1334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riera M, Anguiano L, Clotet S, Roca-Ho H, Rebull M, Pascual J, et al. Paricalcitol modulates ACE2 shedding and renal ADAM17 in NOD mice beyond proteinuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;310:F534–46. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00082.2015. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00082.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54•.Lin M, Gao P, Zhao T, He L, Li M, Li Y, et al. Calcitriol regulates angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin converting-enzyme 2 in diabetic kidney disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2016;43:397–406. doi: 10.1007/s11033-016-3971-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-016-3971-5This study demonstrates that calcitriol reduces the renal ACE to ACE2 ratio in diabetic rats with reduction in proteinuria. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oudit GY, Liu GC, Zhong J, Basu R, Chow FL, Zhou J, et al. Human recombinant ACE2 reduces the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2010;59:529–38. doi: 10.2337/db09-1218. https://doi.org/10.2337/db09-1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin HY, Chen LJ, Zhang ZZ, Xu YL, Song B, Xu R, et al. Deletion of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 exacerbates renal inflammation and injury in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice through modulation of the nephrin and TNF-alpha-TNFRSF1A signaling. J Transl Med. 2015;13:255. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0616-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-015-0616-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57•.Zheng Y, Tang L, Huang W, Yan R, Ren F, Luo L, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Ang-(1-7) in ameliorating HFD-induced renal injury through LDLr-SREBP2-SCAP pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136187. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136187This study demonstrates that administration of Ang(1–7) reduces lipid-induced renal injury, inflammation, and lipid deposition through the LDL receptor, SREBP-2, and SCAP pathway. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Velkoska E, Patel SK, Griggs K, Pickering RJ, Tikellis C, Burrell LM. Short-term treatment with diminazene aceturate ameliorates the reduction in kidney ACE2 activity in rats with subtotal nephrectomy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118758. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118758. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anguiano L, Riera M, Pascual J, Valdivielso JM, Barrios C, Betriu A, et al. NEFRONA study. Circulating angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in patients with chronic kidney disease without previous history of cardiovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1176–85. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv025. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfv025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abe M, Maruyama N, Oikawa O, Maruyama T, Okada K, Soma M. Urinary ACE2 is associated with urinary L-FABP and albuminuria in patients with chronic kidney disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2015;75:421–7. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2015.1054871. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365513.2015.1054871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bae EH, Fang F, Williams VR, Konvalinka A, Zhou X, Patel VB, et al. Murine recombinant angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 attenuates kidney injury in experimental Alport syndrome. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1347–61. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]