Abstract

Background

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition is an important process in embryonic development, fibrosis, and cancer metastasis. During the progression of epithelial cancer, activation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition is tightly associated with metastasis, stemness and drug resistance. However, the role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-epithelial cancer is relatively unclear.

Main body

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors are critical in both myeloid and lymphoid development. Growing evidence indicates their roles in cancer cells to promote leukemia and lymphoma progression. The expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors can cause the differentiation of indolent type to the aggressive type of lymphoma. Their up-regulation confers cancer cells resistant to chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and radiotherapy. Conversely, the down-regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors, monoclonal antibodies, induce lymphoma cells apoptosis.

Conclusions

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition transcription factors are potentially important prognostic or predictive factors and treatment targets for leukemia and lymphoma.

Keywords: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Leukemia, Lymphoma

Background

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is the process of epithelial cells transforming into mesenchymal cells. Cells that undergo EMT have typical morphological changes, including disruption of intercellular junctions, loss of cell polarity, reorganization of the cytoskeleton, and increased cell motility [1, 2]. Therefore, in most experimental models, epithelial markers (E-cadherin and α- and β-catenin), mesenchymal markers (N-cadherin, vimentin, and fibronectin) and morphological changes are examined as indicators to confirm the occurrence of EMT. EMT is classified into three types according to the EMT meeting held in 2007 [3]. These three types have different biological processes that lead to a distinct functional consequence. Type 1 EMT is associated with embryogenesis. At the stage of embryogenesis, EMT facilitates successful implantation [4] and gastrulation [1]. Type 2 EMT is associated with wound healing, tissue regeneration, and organ fibrosis. Type 3 EMT develops in epithelial cancer cells, which is associated with tumor invasion and metastasis, resulting in a worse prognosis.

EMT permits cancer cells to acquire migratory, invasive, and stem-like properties [5]. The reverse process of EMT, i.e., mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), is an important process for cancer cell re-differentiation and metastatic colonization [6]. The evidence linked between stemness and EMT is well documented. However, contradictory results have indicated the inhibition of EMT also promotes cancer stemness, which may be explained by the concept of partial EMT [7]. Furthermore, cancer stemness is independent of EMT, implying that EMT-TFs, the critical mediators for EMT, regulate cancer cells stemness separately from EMT in solid tumors [8].

Intriguingly, accumulating evidence supports the involvement of EMT-TFs in hematologic diseases. Twist1 is highly expressed in hematopoietic and leukemic stem cells [9]. The expression of Twist1 is implicated in hematopoiesis. Twist1 confers cancer cell self-renewal and apoptosis resistance both in solid tumors [10] and leukemia [11]. The Snail family also promotes lymphoid development by blocking apoptosis [12]. These findings have led to the investigation of the role of EMT-TFs in hematological malignancies. In this article, we will review the relevant studies on EMT-TFs in hematological malignancies and discuss the potential of EMT-TFs as biomarkers.

EMT-transcription factors

One of the major triggering events for EMT is the activation of EMT-TFs, such as Snail1, Twist1, zinc finger E–box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1), and ZEB2. These EMT-TFs often control the expression of each other and cooperate with other TFs to regulate the expression of target genes; EMT-TFs often function as repressors for epithelial genes and activators for mesenchymal genes [7, 13, 14]. The Twist family consists of Twist1 and Twist2, which are important EMT-TFs. Twist, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor originally recognized in Drosophila, is a master regulator of gastrulation and mesoderm development [15]. In humans, Twist is overexpressed in many types of cancers, such as head and neck cancer [16], hepatocellular carcinoma [17], and breast cancer [18], where it represents a poor prognosis. Twist1 induces EMT with the recruitment of methyltransferases to directly repress the promoter of CDH1 that encodes E-cadherin [19]. Twist1 activates the transcription of BMI1 and cooperates with it to enhance stemness [10]. Twist1 also suppresses let-7i to induce the mesenchymal-type movement of cancer cells [20]. Moreover, down-regulation of let-7i also activates the chromatin modifier AT-rich interacting domain 3B (ARID3B) to promote the expression of stemness genes through histone modifications [21]. To overcome oncogene-mediated senescence, Twist1 cooperates with Myc to override p53 and Rb-dependent programmed cell death [22]. In hypoxic microenvironments, hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1α) directly binds to the promoter of Twist1 to induce EMT [23]. Twist1 is also essential in TNF-α-induced EMT and is up-regulated by nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) directly [24]. Twist2, which shares more than 90% identity with Twist1, also promotes EMT in human cancers. However, the expression pattern of Twist2 differs from that of Twist1 [25].

The Snail family contains Snail1 (Snail), Snail2 (Slug) and Snail3 (Smuc). The structure of Snail has two highly conserved domains. The C-terminal zinc finger domains are responsible for binding to the promoter of E-cadherin [26], whereas the N-terminal SNAG domain allows for co-repressors and epigenetic remodeling complex binding [27]. Snail1 is phosphorylated by GSK-β leading to ubiquitination of Snail1 [28]. However, in the presence of Wnt signaling, GSK-β is repressed to stabilize Snail1 activity and trigger EMT [29]. Moreover, Snail1 and Twist1 have independent but collaborative effects on EMT [17]. Snail1 induced cancer stemness via activating the expression of IL-8 or miR-146a [30, 31]. Snail1 is an important mediator in the different signaling pathways that induce EMT, such as the Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 (NBS1)-Snail1 axis and the TGF-β/Smads/HMGA2/Snail1 axis [32, 33]. In hypoxia-mediated EMT, Notch directly up-regulates Snail1 [34]. NF-κB also up-regulates and stabilizes Snail1 expression via transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms [35]. Similar to Snail1, Snail2 is also phosphorylated by GSK-β and subsequently ubiquitinated by β-Trcp1 [36]. Snail2 is up-regulated by Notch to induce EMT with an increase of cell migration and loss of cell-cell junctions [37]. Snail2 acts synergistically with Snail1 to down-regulate E-cadherin [38]. Snail2 also activates another EMT-TF, ZEB1, and cooperates with it to promote EMT [39]. Regarding anti-apoptotic activity, both Snail2 and Snail1 repress multiple factors involved in programmed cell death [40]. Among these, Snail2 represses p53 expression, leading to apoptosis resistance [41]. Snail3 plays roles in mesodermal formation during embryogenesis but associated studies are limited [42].

The ZEB family, including ZEB1 and ZEB2 (SIP1), contain two zinc-finger clusters to bind to E-boxes and a central region. ZEB1 down-regulates E-cadherin by binding to its promoter with the recruitment of a C-terminal-binding protein (CtBP) and LDS1 to form the CoREST-CtBP corepressor complex for demethylation [43]. Independent of CtBP, chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1 also cooperates with ZEB1 to repress E-cadherin [44]. Alternatively, ZEB2 directly represses tight junction and desmosome proteins, leading to a loss of cell-cell adhesions [45]. ZEB also plays a role in cell invasion [46], loss of polarity and metastasis [47]. The ZEB family is regulated by other EMT-TFs, both Snail1 and Twist1 can up-regulate and cooperate with ZEB1 to induce EMT [48]. TGF-β signaling induces the expression of ZEB1 through Ets-1 [49]. Other growth factors induce ZEB expression through Ras-MAPK and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways [14]. In contrast, the ZEB family is repressed by the miR-200 family, which forms a feedback loop to regulate ZEB activity post-transcriptionally [50].

Inducers for EMT-TFs

TGF-β is a crucial EMT inducer that up-regulates important transcription factors in EMT. Although TGF-β is indicated as a tumor suppressor, cancer cells can disable the tumor-suppressive arm of the TGF-β pathway to promote advanced stage tumor invasiveness and metastasis through EMT [51, 52]. The “TGF-β Paradox” reflects the dynamic alterations that occur within the developing carcinoma and the composition of tumor microenvironment [51, 53]. In cancer cells, TGF-β that deposited in the surrounding stroma induces the expression of ZEB1 and Snail1 in tumor cells, thereby triggering EMT [54, 55]. With Smad complexes and HMGA2, TGF-β also up-regulates the Twist and Snail families and cooperates with them to promote EMT [56]. NF-κB is also indicated essentially for EMT in Ras- and TGF-β–dependent signaling pathways [57]. Furthermore, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) induce EMT through the PI3K-AKT, ERK, MARK or STAT pathway [58] and platelet-derived growth factors induce EMT by promoting nuclear translocation of β-catenin [59]. Vascular endothelial growth factor and Wnt signaling inhibit GSK-3β to stabilize Snail1 and subsequently induce EMT [29, 60]. Hepatocyte growth factor up-regulates Snail1 through the MAPK/Egr-1 signaling pathway [61]. Notch induces the expression of Twist1 and the Snail family through Delta-like or Jagged ligands [62], and HIF-1α can directly regulate Twist1-mediated EMT in response to hypoxia [16]. These signaling pathways participate in crosstalk for intracellular transduction and active the EMT-TFs play critical role in EMT [63].

EMT-TFs in hematopoiesis

Accumulating evidence demonstrates that EMT-TFs are critical for the regulation of hematopoietic development. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have the potential to generate various lymphoid and myeloid lineages. Meanwhile, EMT-TFs are critical for regulating hematopoietic development. For example, Dong, C.Y. et al. indicated that Twist1 is highly expressed in HSCs and its expression declines with differentiation, but the enforced Twist1 expression in HSCs increases proliferation, differentiation toward myeloid cells, whereas knockdown of Twist1 impairs the ability [9]. The result indicated.

Twist-1 is not only critical in the maintenance of HSCs and self-renewal capacity but also participated in the development of myeloid lineage [9]. Conversely, Twist2, which markedly increases in mature myeloid populations, negatively regulates myeloid development, through inhibiting RUNX1, C/EBPα, proinflammatory cytokines and promoting regulatory cytokines in myeloid cells [64].

Snail2 is implicated in hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. The stem cell factor c-kit (SCF/c-kit) signaling pathway, critical in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal [65], up-regulates c-Myc and FoxM1 expression, which promotes Snail2 expression [66]. Moreover, Snail2 negatively regulates c-kit by directly interacting with the c-kit promoter. Thus, the balance of Snail2 and c-kit in the SCF/c-kit-Myc/FoxM1/Snail2 pathway controls hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal [67].The Snail family is also involved in lymphoid development. Initially, the E2A-HLF fusion gene was found to transform pro-B lymphocytes by blocking apoptosis [12] and Inukai et al. further discovered that Snail2 was up-regulated by the E2A-HLF oncoprotein in a pre-B cell line [68]. Furthermore, the expression of Snail2 prolonged IL-3 dependent cell survival in the absence of cytokines and promoted pro-B cell malignant transformation, which demonstrates the anti-apoptotic activity of Snail2 in lymphoid development. In contrast, Dahlem et al. found that overexpression of Snail3 suppressed lymphoid cell differentiation [69]. A Snail3-expression retrovirus vector was transduced into irradiated mice, which resulted in normal numbers of hematopoietic precursor cells but impairment of lymphocyte development. The same study also indicated that Snail3 was overexpressed in developing T cells and knockdown of Snail3 alone had no effect on T cell development [69]. These data suggested that Snail2 played a more important role in lymphoid development.

Moreover, ZEB2 is essential for murine embryonic hematopoietic differentiation and mobilization [70]. ZEB1, but not ZEB2, which is highly expressed in T cells from the thymus [71], contains repressor domains that function in T lymphocytes [72].

EMT-TFs in myeloid malignancies

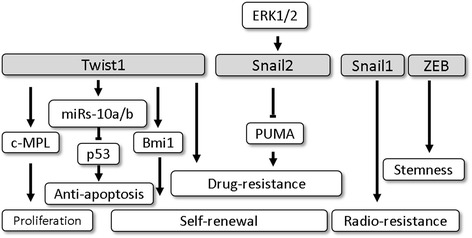

These major EMT-TFs that play a role in myeloid malignancies are summarized in Fig. 1. Twist1 is highly expressed in human leukemia stem cells, which maintain leukemia stem cell function [9, 73]. Twist1 promotes leukemia cell growth and colony formation through the Twist/c-MPL axis, and knockdown of Twist1 inhibits tumor growth [73]. Twist1 also indicated significantly increases in CD34+ myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) cells by regulating the anti-apoptotic activity through the Twist1/ miRs-10a/b/p53 axis, therefore, the expression of Twsit1 is and associated with disease progression [74, 75]. Bmi1, which maintains chromatin silencing through repression of the INK4A–ARF locus [76], is essential in Twist1-induced EMT [10]. Park IL et al. demonstrated that Bmi1 was essential for self-renewal in HSCs and a lack of Bmi1 resulted in marked reduction in HSCs [77]. In leukemia stem cells, Lessard J et al. found that Bmi1 had a key role in regulating the proliferative activity [78], and thus its expression was associated with the progression from MDS to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [79]. In contrast, repression of Bmi1 impaired self-renewal and induced apoptosis in leukemia stem cells [80]. Recently, evidence has indicated that Twist1 confers AML cell self-renewal and apoptosis resistance via a Twist1-Bmi1 axis [11]. Taken together, these studies highlight the importance of the Twist1-Bmi1 axis in the regulation of self-renewal in both hematopoietic and leukemia stem cells.

Fig. 1.

The role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-transcription factors in myeloid malignancies. The major EMT-TFs in myeloid malignancies are Twist1, Snail1, Snail2, and ZEB. Twist1 up-regulates proto-oncogene c-MPL expression to promote leukemia cell growth. The Twist1/miRs-10a/b axis down-regulates p53-mediated cell apoptosis. Twist1 up-regulates and cooperates with Bmi1 to maintain leukemia cell self-renewal. Twist1 expression is also associated with drug resistance to daunorubicin and mitoxantrone in AML and imatinib mesylate in CML. ERK1/2-induced Snail2 expression leads to a down-regulation of PUMA and enhanced drug resistance in AML and CML. Alternatively, overexpression of Snail1 results in anti-apoptotic activity and radio-resistance. ZEB2 is an essential transcription factor for AML cells to maintain stemness

The Twist1 expression may also cause drug resistance. Nan et al. reported that Twist1 expression was associated with the resistance to daunorubicin and mitoxantrone, which leads to the poor prognosis. However, the molecular and cytogenetic risk was unknown in this study [73]. On the contrary, another study showed that the aggressive disease phenotype of AML with overexpression of Twist1 had a higher response to cytarabine treatment, leading to a favorable outcome [11]. This result indicated that Twist1 overexpression was associated with good molecular/cytogenetic risk, which may explain the better prognosis. On the other hands, the interaction between Twist1 and signaling pathways in a low-risk AML subtype requires further study. Regarding chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), the Twist1 expression level in CD34+ CML cells acted as a prognostic factor and also a biomarker for early detection of tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance irrespective of any other resistance mechanism. Although the link between Twist1 and Bcr-Abl translocation is unclear [81], Twist1 may still serve as an important predictive marker for treatment and prognosis in myeloid malignancies. Twist2, in contrast to Twist1, was identified as a negative regulator of myeloid progenitor cells [64]. Twist2 directly up-regulated p21 expression, which inhibited the growth of AML cells [82]. The frequent hypermethylation of Twist2 in human AML resulted in the inactivation of Twist2 and subsequent tumor growth.

In Bcr-Ablp190 transgenic mice, Pe’rez-Mancera et al. found that Snail2 was up-regulated and essential for promoting leukemogenesis [83]. Snail2 expression also conferred leukemia cell resistance to apoptosis, whereas blocking Snail2 induced apoptosis [84]. The expression of Snail2 is induced by ERK1/2, which leads to down-regulation of p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and subsequent chemoresistance to cytarabine [85] and Adriamycin [86]. In a CML cell line, Mancini et al. showed that Bcr-Ablp210 regulated Snail2 expression via ERK1/2, which led to imatinib mesylate resistance [87]. In Snail1-expressing mice, leukemia formation could be induced and the expression of Snail1 also promoted resistance to programmed cell death resulting in radio-resistance [88]. Taken together, the Snail family, especially Snail2, may control self-renewal, anti-apoptosis and treatment resistance in leukemia, which makes this family a potential target for leukemia treatment. Furthermore, ZEB2 was identified as an essential transcription factor for leukemia cell stemness maintenance, and loss of ZEB2 led to aberrant differentiation and decreased proliferation [89].

EMT-TFs in lymphoid malignancies

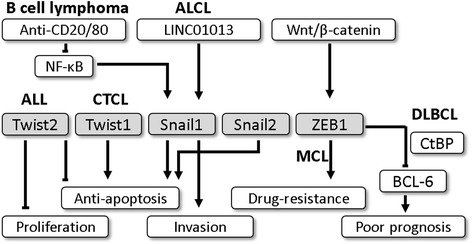

The roles of EMT-TFs in lymphoid malignancies are summarized in Fig. 2. In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Thathia et al. found that inactivation of Twist2 via promoter hypermethylation was common in humans [90]. Re-introduced Twist2 gene expression in an ALL cell line inhibited tumor growth and induced apoptosis to cytotoxic agents. Hence, the expression of Twist2 is a negative regulator of ALL cell survival, which is consistent with its role in AML as mentioned above [82]. These data identify Twist2 as a potential target for drug development for acute leukemia.

Fig. 2.

The role of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-transcription factors in lymphoid malignancies, In lymphoid malignancies, Twist1 is overexpressed in Sezary syndrome (SS), a rare cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL), and its expression may be associated with anti-apoptotic effects. In contrast, the expression of Twist2 inhibits tumor growth and induces apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). In B cell lymphoma, NF-κB and the upregulation of Snail1 promote lymphoma cell resistance to apoptosis, whereas anti-CD20 and anti-CD80 monoclonal antibodies reverse the effect. Moreover, non-coding RNA LINC01013 activates Snail1 and enhances the invasion ability of anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL). Snail2 has anti-apoptotic activity during lymphoid development. In diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway induces the expression of ZEB1, which cooperates with CtBP to inhibit Bcl-6, leading to the poor prognosis of B cell lymphoma. Similarly, Wnt signaling induces ZEB1 expression in a mantle cell lymphoma cell line and makes MCL cells resistant to chemotherapy

In T cell lymphoma, Sezary syndrome (SS) is a rare cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) with aggressive characteristics, whereas mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of CTCL with an indolent course. By identifying more than 100 genes, Doorn et al. found significantly increased Twist1 gene expression in CD4+ T cells from the peripheral blood of SS patients compared with that from skin lesions of MF patients [91]. Using qPCR for validation, Twist1 mRNA was consistently up-regulated in SS patients but almost undetectable in control samples. Vermeer et al. demonstrated that part of Twist1 overexpression was due to the gain of a chromosomal region that harbors the Twist1 gene [92]. Other mechanisms of Twist1 overexpression in SS have also been reported. For instance, Wong et al. found the genome-wide and Twist1 promoter hypomethylation led to the aberrant expression of Twist1 in SS [93]. Goswami et al. further demonstrated that the frequency and intensity of Twist1 expression by IHC were correlated to clinical stages of SS. The co-expression of Twist1, c-Myc, and p53 suggest that the role of Twist1 in SS progression may be associated with anti-apoptotic activity [94]. With accumulating evidence demonstrating the importance of Twist1 in SS, Michael L. suggested expressing a combination of four genes, including Twist1, to make early, reliable diagnoses of SS [95]. Taken together, these data addressed the critical role of Twist1 in SS. The value of Twist1 in pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic target needs further investigation. Alternatively, Twist2 is involved in Sezary cell apoptosis. Koh et al. found that Twist2 directly repressed the activity of the CD7 promoter via chromatin acetylation, which resulted in resistance to galectin-1-induced apoptosis [96]. Limited data have been reported on EMT-TFs in other types of T cell lymphoma. In anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), Chung et al. found that a long non-coding RNA, LINC01013, activated Snail1 and downstream fibronectin to enhance the invasion of an ALCL cell line [97]. In diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Lemma et al. indicated that ZEB1 and Slug expression correlated with adverse disease presentation, and the nuclear expression of ZEB1 seems to be the major one that associated with unfavorable outcomes [98]. The previous study showed that ZEB1 and CtBP formed a complex to repress the promoter of B-cell lymphoma 6 protein (Bcl-6), a proto-oncogene that serves as a good prognostic factor in DLBCL [99]. This finding may explain the poor prognosis of ZEB1 expression in DLBCL.

ZEB1 also serves as a poor prognostic factor in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) [100, 101]. Sanchez-Tillo et al. demonstrated that ZEB1 expression in MCL cells was induced by Wnt signaling pathway, and the Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay further confirmed that Beta-catenin binds to the promoter of ZEB1 to regulate its expression [101]. The activation of ZEB1 regulates genes involved in proliferation,apoptosis, and determines a differential response to chemotherapy drugs [101]. These data suggest that ZEB1 is a potential biomarker for prognosis and a therapeutic target for MCL [101]. In B cell lymphoma, anti-CD20 is widely used to treat CD20+ B cell lymphoma through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and sensitization to chemotherapy or TRAIL-mediated apoptosis [102]. Furthermore, Baritaki et al. found anti-CD20 inhibited NF-κB activity and subsequent Snail1 down-regulation, which led to PTEN expression and AKT inactivation [103]. After transfection with Snail1 siRNA, cells were resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. However, knockdown of Snail1 showed opposite results. Similarly, Snail1 also plays a role in B cell lymphoma with anti-CD80 monoclonal antibody treatment [104]. CD80 is a member of B7 co-stimulators expressed on the surface of T cells and activated B cells. Martinez-Paniagua et al. found that anti-CD80 down-regulated NF-κB and downstream protein expression, which suppressed the expression of Snail1 and YY1, leading to the increase of cisplatin- and TRAIL-induced apoptosis of CD80+ Burkitt’s B-NHL cell lines. Therefore, Snail1 may be a novel target for enhancing the response of monoclonal antibodies and cytotoxic agents.

Conclusions

EMT has received increasing attention in hematological malignancies. As in solid tumors, EMT-TFs are also implicated in cancer proliferation, stemness, anti-apoptosis and drug resistance in hematological malignancies. Notably, evidence shows that EMT-TFs are related to chemotherapy and radiotherapy resistance in both myeloid and lymphoid malignancies. These findings make them potential targets for combination with conventional treatments. Determining the diagnostic and prognostic value of EMT-TFs is worthy of future study.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX107-10622BI), Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V107C-071), and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Center of Excellence for Cancer Research (MOHW106-TDU-B-211-144-003).

Abbreviations

- ADCC

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- ALL

-

ac

Ute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- BCL-6

B-cell lymphoma 6 protein

- Bmi1

B cell-specific Moloney murine leukemia virus integration site 1

- ChIP

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CML

Chronic myelogenous leukemia

- CTCL

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma

- DLBCL

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- EMT-TFs

epithelial-mesenchymal transition-transcription factors

- GSK-β

Glycogen synthase kinas-β

- HSCs

Hematopoietic stem cells

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCL

Mantle cell lymphoma

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndromes

- MET

Mesenchymal-epithelial transition

- MF

Mycosis fungoides

- NBS1

Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- PUMA

p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis

- RTKs

Receptors tyrosine kinases

- SCF/c-kit

stem cell factor/c-kit signaling pathway

- Snail1

Snail family zinc finger 1

- SS

Sezary syndrome

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-β

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- Twist1

Twist family bHLH transcription factor 1

- ZEB1

Zinc finger E–box binding homeobox 1

- ZEB2

Zinc finger E–box binding homeobox 2

Authors’ contributions

SCC wrote the manuscript with the help of TTL and MHY. MHY supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

San-Chi Chen, Email: sunkist.chen37@gmail.com.

Tsai-Tsen Liao, Email: tenanmilk@gmail.com.

Muh-Hwa Yang, Phone: 886-228267000, Email: mhyang2@vghtpe.gov.tw.

References

- 1.Hay ED. An overview of epithelio-mesenchymal transformation. Acta Anat. 1995;154:8–20. doi: 10.1159/000147748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieto MA. Epithelial plasticity: a common theme in embryonic and cancer cells. Science. 2013;342:1234850. doi: 10.1126/science.1234850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acloque H, Thiery JP, Nieto MA. The physiology and pathology of the EMT. Meeting on the epithelial–Mesenchymal transition. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:322–326. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vicovac L, Aplin JD. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition during trophoblast differentiation. Acta Anat. 1996;156:202–216. doi: 10.1159/000147847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieto MA, Huang RY, Jackson RA, Thiery JP. Emt: 2016. Cell. 2016;166:21–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonnomet A, et al. A dynamic in vivo model of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions in circulating tumor cells and metastases of breast cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31:3741–3753. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao TT, Yang MH. Revisiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer metastasis: the connection between epithelial plasticity and stemness. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:792–804. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck B, et al. Different levels of Twist1 regulate skin tumor initiation, stemness, and progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong CY, et al. Twist-1, a novel regulator of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and myeloid lineage development. Stem cells. 2014;32:3173–3182. doi: 10.1002/stem.1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang MH, et al. Bmi1 is essential in Twist1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:982–992. doi: 10.1038/ncb2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CC, et al. Favorable clinical outcome and unique characteristics in association with Twist1 overexpression in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Blood cancer journal. 2015;5:e339. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inaba T, et al. Reversal of apoptosis by the leukaemia-associated E2A-HLF chimaeric transcription factor. Nature. 1996;382:541–544. doi: 10.1038/382541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Craene B, Berx G. Regulatory networks defining EMT during cancer initiation and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:97–110. doi: 10.1038/nrc3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thisse B, Stoetzel C, Gorostiza-Thisse C, Perrin-Schmitt F. Sequence of the twist gene and nuclear localization of its protein in endomesodermal cells of early Drosophila embryos. EMBO J. 1988;7:2175–2183. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang MH, et al. Direct regulation of TWIST by HIF-1alpha promotes metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:295–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang MH, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the independent effect of twist and snail in promoting metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2009;50:1464–1474. doi: 10.1002/hep.23221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang J, et al. Twist, a master regulator of morphogenesis, plays an essential role in tumor metastasis. Cell. 2004;117:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang F, et al. SET8 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and confers TWIST dual transcriptional activities. EMBO J. 2012;31:110–123. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang WH, et al. RAC1 activation mediates Twist1-induced cancer cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:366–374. doi: 10.1038/ncb2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao TT, et al. Let-7 modulates chromatin configuration and target gene repression through regulation of the ARID3B complex. Cell Rep. 2016;14:520–533. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valsesia-Wittmann S, et al. Oncogenic cooperation between H-twist and N-Myc overrides failsafe programs in cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:625–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang MH, Wu KJ. TWIST activation by hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1): implications in metastasis and development. Cell cycle. 2008;7:2090–2096. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.14.6324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li CW, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by TNF-alpha requires NF-kappaB-mediated transcriptional upregulation of Twist1. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1290–1300. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ansieau S, et al. Induction of EMT by twist proteins as a collateral effect of tumor-promoting inactivation of premature senescence. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cano A, et al. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Shi J, Chai K, Ying X, Zhou BP. The role of snail in EMT and tumorigenesis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:963–972. doi: 10.2174/15680096113136660102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinas-Castells R, et al. The hypoxia-controlled FBXL14 ubiquitin ligase targets SNAIL1 for proteasome degradation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3794–3805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.065995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yook JI, et al. A Wnt-Axin2-GSK3beta cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1398–1406. doi: 10.1038/ncb1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang WL, et al. SNAIL regulates interleukin-8 expression, stem cell-like activity, and tumorigenicity of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:279–291. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang WL, et al. MicroRNA-146a directs the symmetric division of snail-dominant colorectal cancer stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:268–280. doi: 10.1038/ncb2910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang MH, et al. Overexpression of NBS1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and co-expression of NBS1 and snail predicts metastasis of head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:1459–1467. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thuault S, et al. HMGA2 and Smads co-regulate SNAIL1 expression during induction of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33437–33446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802016200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahlgren C, Gustafsson MV, Jin S, Poellinger L, Lendahl U. Notch signaling mediates hypoxia-induced tumor cell migration and invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6392–6397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802047105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu Y, et al. Stabilization of snail by NF-kappaB is required for inflammation-induced cell migration and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu ZQ, et al. Canonical Wnt signaling regulates slug activity and links epithelial-mesenchymal transition with epigenetic breast Cancer 1, early onset (BRCA1) repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:16654–16659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205822109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leong KG, et al. Jagged1-mediated notch activation induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through slug-induced repression of E-cadherin. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2935–2948. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Castro Alves C, et al. Slug is overexpressed in gastric carcinomas and may act synergistically with SIP1 and snail in the down-regulation of E-cadherin. J Pathol. 2007;211:507–515. doi: 10.1002/path.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wels C, Joshi S, Koefinger P, Bergler H, Schaider H. Transcriptional activation of ZEB1 by slug leads to cooperative regulation of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition-like phenotype in melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1877–1885. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kajita M, McClinic KN, Wade PA. Aberrant expression of the transcription factors snail and slug alters the response to genotoxic stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7559–7566. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7559-7566.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu WS, et al. Slug antagonizes p53-mediated apoptosis of hematopoietic progenitors by repressing puma. Cell. 2005;123:641–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katoh M, Katoh M. Identification and characterization of human SNAIL3 (SNAI3) gene in silico. Int J Mol Med. 2003;11:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang J, et al. Opposing LSD1 complexes function in developmental gene activation and repression programmes. Nature. 2007;446:882–887. doi: 10.1038/nature05671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanchez-Tillo E, et al. ZEB1 represses E-cadherin and induces an EMT by recruiting the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling protein BRG1. Oncogene. 2010;29:3490–3500. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vandewalle C, et al. SIP1/ZEB2 induces EMT by repressing genes of different epithelial cell–cell junctions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6566–6578. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Comijn J, et al. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spaderna S, et al. The transcriptional repressor ZEB1 promotes metastasis and loss of cell polarity in cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:537–544. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dave N, et al. Functional cooperation between Snail1 and twist in the regulation of ZEB1 expression during epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12024–12032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.168625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shirakihara T, Saitoh M, Miyazono K. Differential regulation of epithelial and mesenchymal markers by deltaEF1 proteins in epithelial mesenchymal transition induced by TGF-beta. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3533–3544. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brabletz S, Brabletz T. The ZEB/miR-200 feedback loop--a motor of cellular plasticity in development and cancer? EMBO Rep. 2010;11:670–677. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miettinen PJ, Ebner R, Lopez AR, Derynck R. TGF-beta induced transdifferentiation of mammary epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells: involvement of type I receptors. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:2021–2036. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor MA, Lee YH, Schiemann WP. Role of TGF-beta and the tumor microenvironment during mammary tumorigenesis. Gene Expr. 2011;15:117–132. doi: 10.3727/105221611x13176664479322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Korpal M, Lee ES, Hu G, Kang Y. The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14910–14914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zavadil J, Bottinger EP. TGF-beta and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene. 2005;24:5764–5774. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thuault S, et al. Transforming growth factor-β employs HMGA2 to elicit epithelial–mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:175–183. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huber MA, et al. NF-kappaB is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a model of breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:569–581. doi: 10.1172/JCI21358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang L, Lin C, Liu ZR. P68 RNA helicase mediates PDGF-induced epithelial mesenchymal transition by displacing Axin from beta-catenin. Cell. 2006;127:139–155. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wanami LS, Chen HY, Peiro S, Garcia de Herreros A, Bachelder RE. Vascular endothelial growth factor-a stimulates snail expression in breast tumor cells: implications for tumor progression. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2448–2453. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grotegut S, von Schweinitz D, Christofori G, Lehembre F. Hepatocyte growth factor induces cell scattering through MAPK/Egr-1-mediated upregulation of snail. EMBO J. 2006;25:3534–3545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Z, Li Y, Kong D, Sarkar FH. The role of notch signaling pathway in epithelial-Mesenchymal transition (EMT) during development and tumor aggressiveness. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:745–751. doi: 10.2174/138945010791170860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moustakas A, Heldin CH. Signaling networks guiding epithelial-mesenchymal transitions during embryogenesis and cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1512–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharabi AB, et al. Twist-2 controls myeloid lineage development and function. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilson A, et al. C-Myc controls the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2747–2763. doi: 10.1101/gad.313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perez-Losada J, et al. Zinc-finger transcription factor slug contributes to the function of the stem cell factor c-kit signaling pathway. Blood. 2002;100:1274–1286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Z, et al. A novel slug-containing negative-feedback loop regulates SCF/c-kit-mediated hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Leukemia. 2017;31:403–413. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Inukai T, et al. SLUG, a ces-1-related zinc finger transcription factor gene with antiapoptotic activity, is a downstream target of the E2A-HLF oncoprotein. Mol Cell. 1999;4:343–352. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dahlem T, Cho S, Spangrude GJ, Weis JJ, Weis JH. Overexpression of Snai3 suppresses lymphoid- and enhances myeloid-cell differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1038–1043. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goossens S, et al. The EMT regulator Zeb2/Sip1 is essential for murine embryonic hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell differentiation and mobilization. Blood. 2011;117:5620–5630. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-300236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Postigo AA, Dean DC. Differential expression and function of members of the zfh-1 family of zinc finger/homeodomain repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6391–6396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Postigo AA, Dean DC. Independent repressor domains in ZEB regulate muscle and T-cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7961–7971. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.7961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang N, et al. TWIST-1 promotes cell growth, drug resistance and progenitor clonogenic capacities in myeloid leukemia and is a novel poor prognostic factor in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2015;6:20977–20992. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li X, Marcondes AM, Gooley TA, Deeg HJ. The helix-loop-helix transcription factor TWIST is dysregulated in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2010;116:2304–2314. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-242313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li X, et al. Transcriptional regulation of miR-10a/b by TWIST-1 in myelodysplastic syndromes. Haematologica. 2013;98:414–419. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.071753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Valk-Lingbeek ME, Bruggeman SW, van Lohuizen M. Stem cells and cancer; the polycomb connection. Cell. 2004;118:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park IK, et al. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:302–305. doi: 10.1038/nature01587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mihara K, et al. Bmi-1 is useful as a novel molecular marker for predicting progression of myelodysplastic syndrome and patient prognosis. Blood. 2006;107:305. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rizo A, et al. Repression of BMI1 in normal and leukemic human CD34(+) cells impairs self-renewal and induces apoptosis. Blood. 2009;114:1498–1505. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cosset E, et al. Deregulation of TWIST-1 in the CD34+ compartment represents a novel prognostic factor in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:1673–1676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang X, et al. Regulation of p21 by TWIST2 contributes to its tumor-suppressor function in human acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2015;34:3000–3010. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perez-Mancera PA, et al. SLUG in cancer development. Oncogene. 2005;24:3073–3082. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dorn DC, Kou CA, Png KJ, Moore MA. The effect of cantharidins on leukemic stem cells. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2186–2199. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu GJ, et al. Knockdown of ERK/slug signals sensitizes HL-60 leukemia cells to Cytarabine via upregulation of PUMA. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:3802–3809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wei CR, Liu J, Yu XJ. Targeting SLUG sensitizes leukemia cells to ADR-induced apoptosis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:22139–22148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mancini M, et al. Zinc-finger transcription factor slug contributes to the survival advantage of chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Signal. 2010;22:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Perez-Mancera PA, et al. Cancer development induced by graded expression of snail in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3449–3461. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li H, et al. The EMT regulator ZEB2 is a novel dependency of human and murine acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;129:497–508. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-714493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thathia SH, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of TWIST2 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia modulates proliferation, cell survival and chemosensitivity. Haematologica. 2012;97:371–378. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.049593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van Doorn R, et al. Aberrant expression of the tyrosine kinase receptor EphA4 and the transcription factor twist in Sezary syndrome identified by gene expression analysis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5578–5586. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vermeer MH, et al. Novel and highly recurrent chromosomal alterations in Sezary syndrome. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2689–2698. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wong HK, et al. Promoter-specific Hypomethylation is associated with overexpression of PLS3, GATA6, and TWIST1 in the Sezary syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2084–2092. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Goswami M, Duvic M, Dougherty A, Ni X. Increased twist expression in advanced stage of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:500–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2012.01883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Michel L, Jean-Louis F, Begue E, Bensussan A, Bagot M. Use of PLS3, twist, CD158k/KIR3DL2, and NKp46 gene expression combination for reliable Sezary syndrome diagnosis. Blood. 2013;121:1477–1478. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-460535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koh HS, et al. Twist2 regulates CD7 expression and galectin-1-induced apoptosis in mature T-cells. Molecules and cells. 2009;28:553–558. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chung IH, et al. The long non-coding RNA LINC01013 enhances invasion of human anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Sci Rep. 2017;7:295. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00382-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lemma S, et al. Biological roles and prognostic values of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition-mediating transcription factors twist, ZEB1 and slug in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Histopathology. 2013;62:326–333. doi: 10.1111/his.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Papadopoulou V, Postigo A, Sanchez-Tillo E, Porter AC, Wagner SD. ZEB1 and CtBP form a repressive complex at a distal promoter element of the BCL6 locus. Biochem J. 2010;427:541–550. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim Y, McLaughlin N, Lindstrom K, Tsukiyama T, Clark DJ. Activation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae HIS3 results in Gcn4p-dependent, SWI/SNF-dependent mobilization of nucleosomes over the entire gene. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:8607–8622. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00678-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sanchez-Tillo E, et al. The EMT activator ZEB1 promotes tumor growth and determines differential response to chemotherapy in mantle cell lymphoma. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:247–257. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jazirehi AR, Huerta-Yepez S, Cheng G, Bonavida B. Rituximab (chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) inhibits the constitutive nuclear factor-{kappa}B signaling pathway in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma B-cell lines: role in sensitization to chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:264–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Baritaki S, et al. The anti-CD20 mAb LFB-R603 interrupts the dysregulated NF-kappaB/snail/RKIP/PTEN resistance loop in B-NHL cells: role in sensitization to TRAIL apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:1683–1694. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Martinez-Paniagua MA, et al. Galiximab signals B-NHL cells and inhibits the activities of NF-kappaB-induced YY1- and snail-resistant factors: mechanism of sensitization to apoptosis by chemoimmunotherapeutic drugs. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:572–581. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]