ABSTRACT

We characterized the synergistic effect produced between pterostilbene and polymyxin B (fractional inhibitory concentration [FIC] index = 0.156 or 0.188) against MCR-producing Escherichia coli strains of both human and animal origins. The time-killing assays showed that either pterostilbene or polymyxin B failed to eradicate the mcr-1- and NDM-positive E. coli strain ZJ487, but the combination eliminated the strain by 1 h postinoculation. The survival rate of mice after intraperitoneal infections was significantly enhanced from 0% to 60% in the group in which combination therapy was applied.

KEYWORDS: MCR-1, Enterobacteriaceae, polymyxin B, inhibitor, pterostilbene

TEXT

The increasing incidence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in human clinical settings is now recognized as one of the most serious global threats to public health (1). Polymyxins, including polymyxin B and polymyxin E (colistin), are a class of multicomponent polypeptide antibiotics that differ by only one amino acid but display similar pharmacodynamics in vitro (2). They are now considered to be one of the “last-line” treatments for serious infections caused by CRE, most of which carry blaNDM or blaPKC (3). The important role of polymyxins in human clinical medicine has led to the reconsideration and restriction of its extensive usage in livestock (4, 5).

The spread of the plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-1 is breaking down the previous vulnerability of CRE infections to polymyxin administration (6). To date, the mcr-1 gene has mostly been identified in Escherichia coli isolates from animals, humans, and food samples, but it has also been found in isolates belonging to other enterobacterial species from more than 40 countries (7). Critically, the emergence of mcr-1 makes the development of pan-drug resistance by Enterobacteriaceae and the subsequent global dissemination of these “superbugs” highly likely (8). Therefore, a novel and effective strategy is urgently needed to deal with the serious challenges posed by MCR-1. Herein, we describe the identification of a novel MCR-1 inhibitor, pterostilbene (trans-3,5-dimethoxy-4′-hydroxystilbene), which is obtained from fresh leaves or fruits and has been extensively studied for its potent anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities (9), that enhanced the therapeutic effect of polymyxins both in vitro and in vivo experiments.

We applied a broth microdilution checkerboard method (10) to identify potential synergies between different natural compounds (n = 115) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and polymyxin B, and we examined the antibacterial activities of these combinations against both polymyxin-resistant strains (positive for MCR-1) and polymyxin-sensitive strains (negative for MCR-1) after 24 h of incubation at 37°C. Four of the mcr-1-positive E. coli isolates, namely, ZJ478, ZJ69, ZJ378, and DZ2-12R, were collected during our previous studies (11, 12). The mcr-1-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae strain K7 (13), the mcr-1-negative Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 (14), and E. coli strain ATCC 25922 were used as negative-control strains (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

MIC values of the polymyxin B and pterostilbene combination therapy for each of the tested bacterial isolates

| Strain | Source | Reference | mcr-1 confirmationa | Antibiotic compound | MIC (μg/ml [fold change])b |

FIC index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | Combination | ||||||

| E. coli ZJ478 | Human intraabdominal fluid (blaNDM-1 carrying) | 11 | + | Polymyxin B | 8 | 1 (8) | 0.156 |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli ZJ69 | Human urine | 11 | + | Polymyxin B | 8 | 1 (8) | 0.188 |

| Pterostilbene | 512 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli ZJ378 | Human feces | 11 | + | Polymyxin B | 8 | 1 (8) | 0.156 |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli DZ2-12R | Chicken cloacae | 12 | + | Polymyxin B | 8 | 1 (8) | 0.156 |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli DH5α(pUC19-mcr-1) | Laboratory strain (carries an mcr-1 gene that originated from ZJ478) | + | Polymyxin B | 8 | 2 (4) | 0.313 | |

| Pterostilbene | 512 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli DH5α(pUC19) | Laboratory strain | − | Polymyxin B | 0.5 | 0.25 (2) | 0.563 | |

| Pterostilbene | 512 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli W3110(pUC19-mcr-1) | Laboratory strain (carries an mcr-1 gene that originated from ZJ478) | + | Polymyxin B | 8 | 1 (8) | 0.156 | |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli W3110(pUC19) | Laboratory strain | − | Polymyxin B | 0.5 | 0.25 (2) | 0.531 | |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | Laboratory strain | − | Polymyxin B | 0.5 | 0.25 (2) | 0.531 | |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| S. Typhimurium SL1344 | Derived from the virulent strain SL1344 | 14 | − | Polymyxin B | 1 | 1 (1) | 1.031 |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| A. baumannii ATCC 19606 | Laboratory strain | − | Polymyxin B | 2 | 1 (2) | 0.531 | |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| K. pneumoniae K7 | Human | 13 | − | Polymyxin B | 2 | 2 (1) | 1.031 |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 32 | |||||

| E. coli ZJ478 | Human intraabdominal fluid (blaNDM-1 carrying) | + | Colistin | 8 | 2 (4) | 0.266 | |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 16 | |||||

| E. coli W3110(pUC19-mcr-1) | Laboratory strain (carries an mcr-1 gene that originated from ZJ478) | + | Colistin | 16 | 2 (8) | 0.141 | |

| Pterostilbene | 1,024 | 16 | |||||

+, mcr-1-positive strain; −, mcr-1-negative strain.

All MICs were determined in triplicates.

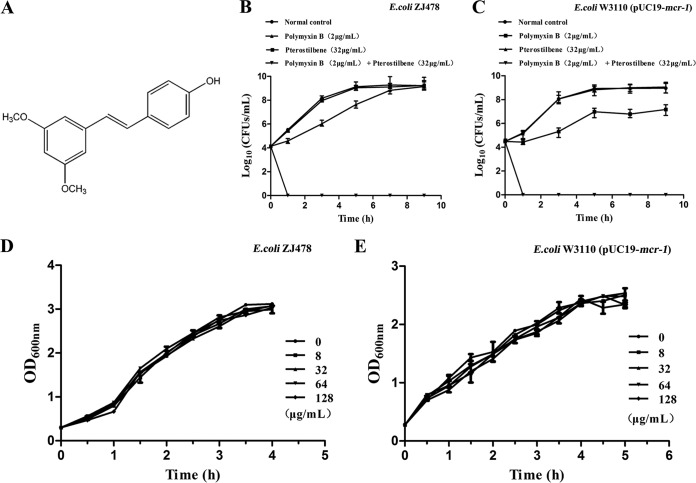

The MIC assay using the CRE strain ZJ478 was performed to screen the efficacies of all tested compounds, and a fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) value of ≤0.5 was defined as indicating a synergistic effect for the combination of the tested natural compound and polymyxin B (15). One of the tested natural compounds, pterostilbene, was identified as having a synergistic effect with polymyxin B (Fig. 1A). The results from an assay applying the broth microdilution checkerboard method further confirmed the synergistic effect between pterostilbene and polymyxin B in mcr-1-positive clinical strains (FIC = 0.156 or 0.188), with an 8-fold decrease in the MIC of polymyxin B (from 8 to 1 μg/ml) in the presence of 32 μg/ml pterostilbene, whereas no synergy was observed in any of the tested polymyxin-sensitive strains (Table 1). Additionally, a synergistic effect between pterostilbene and colistin was also observed in mcr-1-carrying strains (Table 1). The potential bactericidal effect of pterostilbene (32 μg/ml) combined with polymyxin B (2 μg/ml) was then evaluated using time-killing assays (16). This combination had an efficient bactericidal effect against clinical strain ZJ478, killing the bacteria by 1 h postinoculation (Fig. 1B and C). The results from a growth curve assay (17) show that pterostilbene with various concentrations from 0 to 128 μg/ml did not affect the growth of the original mcr-1-positive strain ZJ478 or of W3110 carrying pUC19-mcr-1 (Fig. 1D and E). These findings suggest that pterostilbene could affect the function of MCR-1 and restore the antibacterial activity of polymyxin B.

FIG 1.

Effects of pterostilbene on carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli ZJ478 and E. coli W3110(pUC19-mcr-1) in vitro. (A) Chemical structure of pterostilbene. Time-killing curves of polymyxin B, pterostilbene, polymyxin B plus pterostilbene, and a control treatment (only medium without drug or natural compound) against E. coli ZJ478 (B) and E. coli W3110(pUC19-mcr-1) (C). Growth curves for E. coli ZJ478 (D) and E. coli W3110(pUC19-mcr-1) (E) cultured with various concentrations (0 to 128 μg/ml) of pterostilbene. The data are the means plus standard errors from three independent experiments.

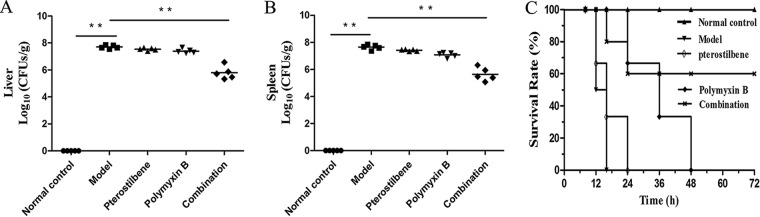

The results of in vivo treatment experiments further illustrate the synergy of pterostilbene in combination with polymyxin B. A total of 85 female 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally with a lethal dose of E. coli ZJ478 (2 × 108 CFU) to cause a systemic infection, and the effects of pterostilbene or polymyxin B monotherapy or of the combination therapy were evaluated. The 68 infected mice were subcutaneously administered polymyxin B (5 mg/kg of body weight, n = 17), pterostilbene (80 mg/kg, n = 17), a combination (n = 17) of pterostilbene (80 mg/kg) and polymyxin B (5 mg/kg), or solvent (n = 17) on the same schedule at 30 min postinfection. An additional 17 mice were used for a blank control. All these mice were monitored for survival until day 3 postinfection. To determine the liver and spleen bacterial loads and perform histopathological experiments, the mice were infected intraperitoneally with a dose of 1 × 108 CFU of E. coli ZJ478 and treated with the same therapeutics. The spleens and livers were harvested at 24 h postinfection. The combination treatment led to significant remission of liver and spleen pathological damage, as demonstrated by histopathology (see Fig. S1, black arrows). Additionally, the combination therapy significantly reduced the bacterial loads in the spleen and liver following subcutaneous administration (P < 0.01). A reduction in CFU counts of more than one order of magnitude was observed, on average, in the livers and spleens of the mice in the combination therapy group compared with those in the organs of groups treated with pterostilbene or polymyxin B alone (Fig. 2A and B). The administration of the combination therapy significantly improved the survival rate, with survival increasing from 0% (solvent-treated controls) to 60% (combination therapy group) (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, neither pterostilbene nor polymyxin B alone was able to prevent lethality following infection with E. coli ZJ478. Together, these results indicate that the combination of polymyxin B and pterostilbene may be efficient for treating infections caused by mcr-1-positive and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae.

FIG 2.

Effects of pterostilbene and polymyxin B combination therapy in vivo. Mice were infected with carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli ZJ478 after treatment with pterostilbene, polymyxin B, pterostilbene combined with polymyxin B (combination), or a control solvent (model) or were left uninfected (normal control). Bacterial loads in the livers (A) and spleens (B). **, P < 0.01. (C) The survival of the mice was monitored for 3 days postinfection. The data are the means from three separate experiments using 5, 6, and 6 mice for the first, second, and third assays, respectively, for a total of 17 mice used for each group.

Here, we propose the use of pterostilbene, an MCR-1 inhibitor, in combination with polymyxins as a treatment against colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (18). Pterostilbene reportedly exhibits antibacterial activity against drug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus without exerting unacceptable cytotoxicity (0.01, 0.05, and 0.125 mM) on mammalian cells (19), and the oral administration of a high dose (3,000 mg/kg/day) of pterostilbene for approximately 30 days is not associated with significant local or systemic toxicity in mice (20). Pterostilbene is also generally safe for human consumption at doses of up to 250 mg per day and functions as a dietary supplement to decrease the risk of coronary heart disease (21). All these results indicate that this natural compound is likely to be safe if applied in human clinical practice. However, the exact mode of MCR-1 inhibition by pterostilbene still needs to be further examined.

In addition to the global spread of mcr-1, another widely disseminated mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-3, has been found in European countries and China (22, 23). Our preliminary experiments in one mcr-3-positive strain demonstrated that pterostilbene is equally effective in combination with polymyxin B against this novel mcr-carrying strain (see Table S2), suggesting the potential inhibitory function of the combination therapy on other mcr variant-carrying isolates. However, further studies on the synergistic mechanism and the potential effect of this combination therapy on other MCR-3-producing strains are still needed.

In conclusion, this study shows that the combination of polymyxins with pterostilbene is a promising alternative treatment option for combating infections caused by MCR-positive carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Selectively targeting MCR using the natural compound pterostilbene is an attractive strategy, as this approach may not exert the direct selective pressure associated with current antimicrobial agents. Further studies, including preclinical investigations of inhibitor-antibiotic combinations, are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of this combination against additional MCR-producing bacterial species.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0501500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31422055 and 81661138002), and the National Key Technology R&D Program (no. 2016YFD 05013).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02146-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Psichogiou M, Tassios PT, Daikos GL. 2012. Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:682–707. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05035-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwa A, Kasiakou SK, Tam VH, Falagas ME. 2007. Polymyxin B: similarities to and differences from colistin (polymyxin E). Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 5:811–821. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mende K, Beckius ML, Zera WC, Onmusleone F, Murray CK, Tribble DR. 2017. Low prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among wounded military personnel. US Army Med Dep J 2017:12–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser T, Finstermeier K, Hantzsch M, Faucheux S, Kaase M, Eckmanns T, Bercker S, Kaisers UX, Lippmann N, Rodloff AC, Thiery J, Lubbert C. 2018. Stalking a lethal superbug by whole-genome sequencing and phylogenetics: influence on unraveling a major hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Am J Infect Control 46:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pogue JM, Lee J, Marchaim D, Yee V, Zhao JJ, Chopra T, Lephart P, Kaye KS. 2011. Incidence of and risk factors for colistin-associated nephrotoxicity in a large academic health system. Clin Infect Dis 53:879–884. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tian G, Dong B, Huang X. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Zhao X, Che J, Xiong Y, Xu Y, Zhang L, Lan R, Xia L, Walsh TR, Xu J. 2017. Detection and dissemination of the colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, from isolates and faecal samples in China. J Med Microbiol 66:119–125. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giamarellou H. 2016. Epidemiology of infections caused by polymyxin-resistant pathogens. Int J Antimicrob Agents 48:614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roupe KA, Remsberg CM, Yanez JA, Davies NM. 2006. Pharmacometrics of stilbenes: seguing towards the clinic. Curr Clin Pharmacol 1:81–101. doi: 10.2174/157488406775268246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espinel-Ingroff A, Colombo AL, Cordoba S, Dufresne PJ, Fuller J, Ghannoum M, Gonzalez GM, Guarro J, Kidd SE, Meis JF, Melhem TM, Pelaez T, Pfaller MA, Szeszs MW, Takahaschi JP, Tortorano AM, Wiederhold NP, Turnidge J. 2015. International evaluation of MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff value (ECV) definitions for Fusarium species identified by molecular methods for the CLSI broth microdilution method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:1079–1084. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02456-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Tian GB, Zhang R, Shen Y, Tyrrell JM, Huang X, Zhou H, Lei L, Li HY, Doi Y, Fang Y, Ren H, Zhong LL, Shen Z, Zeng KJ, Wang S, Liu JH, Wu C, Walsh TR, Shen J. 2017. Prevalence, risk factors, outcomes, and molecular epidemiology of mcr-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae in patients and healthy adults from China: an epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:390–399. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Zhang R, Li J, Wu Z, Yin W, Schwarz S, Tyrrell JM, Zheng Y, Wang S, Shen Z, Liu Z, Liu J, Lei L, Li M, Zhang Q, Wu C, Zhang Q, Wu Y, Walsh TR, Shen J. 2017. Comprehensive resistome analysis reveals the prevalence of NDM and MCR-1 in Chinese poultry production. Nat Microbiol 2:16260. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu J, Liu X, Li Y, Han W, Lei L, Yang Y, Zhao H, Gao Y, Song J, Lu R, Sun C, Feng X. 2012. A method for generation phage cocktail with great therapeutic potential. PLoS One 7:e31698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulig PA, Curtiss R III. 1987. Plasmid-associated virulence of Salmonella Typhimurium. Infect Immun 55:2891–2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma L, Wang Y, Wang M, Tian Y, Wei K, Liu H, Hui W, Jie D, Zhou C. 2016. Effective antimicrobial activity of Cbf-14, derived from a cathelin-like domain, against penicillin-resistant bacteria. Biomaterials 87:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen PJ, Labthavikul P, Jones CH, Bradford PA. 2006. In vitro antibacterial activities of tigecycline in combination with other antimicrobial agents determined by chequerboard and time-kill kinetic analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 57:573–576. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Dong J, Qiu JZ, Wang JF, Luo MJ, Li HE, Leng BF, Ren WZ, Deng XM. 2011. Peppermint oil decreases the production of virulence-associated exoproteins by Staphylococcus aureus. Molecules 16:1642–1654. doi: 10.3390/molecules16021642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King AM, Reidyu SA, Wang W, King DT, Pascale GD, Strynadka NC, Walsh TR, Coombes BK, Wright GD. 2014. AMA overcomes antibiotic resistance by NDM and VIM metallo-β-lactamases. Nature 510:503–506. doi: 10.1038/nature13445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang SC, Tseng CH, Wang PW, Lu PL, Weng YH, Yen FL, Fang JY. 2017. Pterostilbene, a methoxylated resveratrol derivative, efficiently eradicates planktonic, biofilm, and intracellular MRSA by topical application. Front Microbiol 8:1103. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz MJ, Fernández M, Picó Y, Mañes J, Asensi M, Carda C, Asensio G, Estrela JM. 2009. Dietary administration of high doses of pterostilbene and quercetin to mice is not toxic. J Agric Food Chem 57:3180–3186. doi: 10.1021/jf803579e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riche DM, McEwen CL, Riche KD, Sherman JJ, Wofford MR, Deschamp D, Griswold M. 2013. Analysis of safety from a human clinical trial with pterostilbene. J Toxicol 2013:463595. doi: 10.1155/2013/463595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin W, Li H, Shen Y, Liu Z, Wang S, Shen Z, Zhang R, Walsh TR, Shen J, Wang Y. 2017. Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. mBio 8:e00543–17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00543-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kluytmans J. 2017. Plasmid-encoded colistin resistance: mcr-one, two, three and counting. Euro Surveill 22:pii=30588. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.31.30588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.