ABSTRACT

We aimed to prospectively validate an optimized combination dosage regimen against a clinical carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) isolate (imipenem MIC, 32 mg/liter; tobramycin MIC, 2 mg/liter). Imipenem at constant concentrations (7.6, 13.4, and 23.3 mg/liter, reflecting a range of clearances) was simulated in a 7-day hollow-fiber infection model (inoculum, ∼107.2 CFU/ml) with and without tobramycin (7 mg/kg q24h, 0.5-h infusions). While monotherapies achieved no killing or failed by 24 h, this rationally optimized combination achieved >5 log10 bacterial killing and suppressed resistance.

KEYWORDS: Acinetobacter baumannii, dynamic hollow-fiber infection model, synergy, mathematical modeling, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, carbapenem resistance, mechanism based, mechanistic

TEXT

Acinetobacter baumannii has an exceptional propensity for emergence of resistance against commonly used antibiotics (1, 2); current treatment options are extremely limited (3, 4). While carbapenems may combat infections by susceptible A. baumannii, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii (CRAB) isolates now comprise more than half of the isolates in the United States and elsewhere (3, 5, 6). Aminoglycosides in monotherapy can achieve substantial bacterial killing; however, this is followed by rapid and extensive regrowth with emergence of resistance (7, 8). Overall, combination therapy holds promise to treat serious infections by CRAB but needs to be optimized.

(Part of this work was presented at the Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy [ICAAC], San Diego, CA, 18 to 21 September 2015.)

We previously designed an imipenem-plus-tobramycin combination dosage regimen against a clinical CRAB isolate based on static concentration time-kill experiments (SCTK), mechanism-based modeling (MBM), and Monte Carlo simulations (9). The optimized regimen was imipenem 4 g/day continuous infusion with a 1-g loading dose combined with tobramycin 7 mg/kg q24h as 0.5-h infusions. Monte Carlo simulations predicted that this combination regimen would achieve >5 log10 killing without regrowth over 7 days in 98.2% of critically ill patients (9).

Very few studies have evaluated β-lactam-plus-aminoglycoside combination regimens against CRAB isolates in the dynamic in vitro hollow-fiber infection model (HFIM) or in in vivo models (10–12). Montero et al. (11) assessed an empirical, nonoptimized imipenem-plus-tobramycin combination in a murine pneumonia model against CRAB. However, no prior study evaluated bacterial killing and resistance suppression of a CRAB isolate for optimized combination dosage regimens in the HFIM.

Our primary objective was to simulate human pharmacokinetics (PK) and evaluate bacterial killing and resistance suppression by a rationally optimized combination dosage regimen against a clinical CRAB isolate. The secondary objective was to assess via MBM the translation from SCTK to the HFIM.

Dynamic hollow-fiber in vitro infection model.

An HFIM (13, 14) was used to simulate the time course of antibiotic concentrations as expected in critically ill patients for the proposed dosage regimen. For imipenem, the median (13.4 mg/liter), 5th percentile (7.6 mg/liter), and 95th percentile (23.3 mg/liter) of the unbound concentrations at steady state during continuous infusion of 4 g/day were simulated. These concentrations were based on Monte Carlo simulations using published population PK models (9, 15, 16). We simulated the two-compartment behavior of tobramycin by changing the pump flow rate at 5 h each day. Our target inoculum of 107.2 CFU/ml was chosen to mirror bacterial densities in severe infections in patients (17–19). Serial viable counts of the total and of resistant populations (on 1.75× and 3× MIC agar plates for imipenem and 3× and 5× MIC plates for tobramycin) were determined over 7 days, and drug concentrations were measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. We developed MBM in S-ADAPT (20–22) and evaluated competing models as described previously (23, 24). Further methodological details are provided in the supplemental material.

Observed PK and viable count profiles.

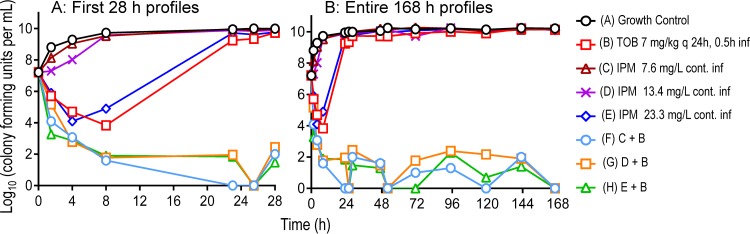

The observed tobramycin concentration-time profiles adequately matched the targeted profiles following administration of 7 mg/kg tobramycin as 0.5-h infusions (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material); unbound peak concentrations for tobramycin were 12.3 mg/liter at 1.2 h, and unbound trough concentrations were 1.37 mg/liter at 23 h. Constant imipenem concentrations of 7.6 (low, 5th percentile) and 13.4 (intermediate, median) mg/liter in monotherapy failed to achieve any killing against isolate FADDI-AB-034 (MIC, 32 mg/liter) at an inoculum of 107.2 CFU/ml. Although 23.3 mg/liter (high, 95th percentile) resulted in 3.1 log10 of killing at 4 h, it was followed by extensive regrowth to ∼10 log10 CFU/ml at 24 h (Fig. 1A). Tobramycin monotherapy (MIC, 2 mg/liter) yielded 3.4 log10 of killing at 8 h followed by extensive regrowth. The combinations of tobramycin with each of the three imipenem concentrations were synergistic, provided near-complete bacterial killing (>5 log10), and prevented regrowth (i.e., total viable counts remained at <2 log10) over 7 days (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Observed viable count profiles (0 to 28 and 0 to 168 h) for the optimized imipenem-plus-tobramycin combination dosage regimen against isolate FADDI-AB034. Imipenem 7.6 (low, 5th percentile), 13.4 (intermediate, median), and 23.3 (high, 95th percentile) mg/liter are 3 clinically relevant imipenem profiles arising from a 4-g/day continuous infusion (with a 1-g loading dose). Observed viable counts below the limit of counting (i.e., <1.0 log10 CFU/ml) were plotted as zero.

Combinations but not monotherapies suppressed resistance.

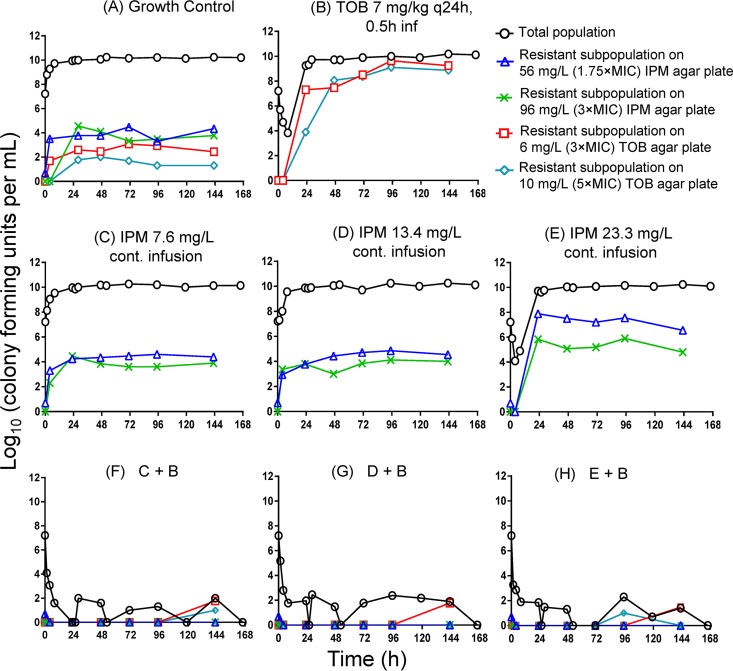

All three combinations of imipenem with tobramycin suppressed resistance over 7 days in the HFIM; only one or two colonies were observed on tobramycin-containing agar plates at 95 and 143 h (Fig. 2F, G, and H). In contrast, tobramycin monotherapy and the high-concentration (23.3-mg/liter) imipenem monotherapy failed, with substantial regrowth and amplification of resistance (Fig. 2B and E). For tobramycin monotherapy, the tobramycin-resistant population at 3× and 5× MIC almost completely replaced the susceptible population by ∼47 h (see Table S1 in the supplemental material and Fig. 2B). Imipenem monotherapy at 23.3 mg/liter created sufficient drug pressure to increase the frequency of the highly resistant subpopulation by 2 to 4 log10 by 23 h (Table S1; Fig. 2E).

FIG 2.

Effect of monotherapies (B to E) and combinations (F to H) on the total bacterial population and resistant populations (quantified on agar plates containing 1.75× or 3× the imipenem MIC and 3× or 5× the tobramycin MIC). While tobramycin monotherapy and imipenem monotherapy at 23.3 mg/liter led to extensive emergence of resistance, all combinations suppressed resistance over 3 days. All four types of antibiotic-containing agar plates were determined for the combinations; most counts were zero on these antibiotic-containing agar plates (F to H).

Mechanism-based modeling.

MBM simultaneously described all treatments and the growth control (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The coefficient of correlation for the observed versus individual (population) fitted log10 viable counts was 0.995 (0.968). Synergy due to imipenem killing the tobramycin-resistant population and vice versa (i.e., subpopulation synergy) was not sufficient to characterize the time course of bacterial killing and regrowth for the combinations. Inclusion of mechanistic synergy with tobramycin enhancing the target site concentration of imipenem was greatly beneficial (P < 0.0001, likelihood-ratio test) (Fig. S2). Tobramycin was modeled to permeabilize the outer bacterial membrane toward imipenem against the imipenem-intermediate and tobramycin-resistant population (i.e., population 3 in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Mechanistic synergy was expressed as a 70-fold decrease (P < 0.0001) of the imipenem concentration resulting in half-maximal killing of population 3 (KC50,IR,IPM) in the presence of at least 1.15 mg/liter (estimated) tobramycin (Table 1); the KC50,IR,IPM was 112 mg/liter in the absence of and 1.60 mg/liter in the presence of at least 1.15 mg/liter tobramycin (Table 1). For populations 1 and 2 in Fig. S4, mechanistic synergy was estimated to be small or absent.

TABLE 1.

Population mean parameter estimates for the imipenem-plus-tobramycin combination model against isolate FADDI-AB034

| Parametera | Symbol (unit) | Population mean value (relative SE, SE %) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial inoculum (log10 CFU/ml) | logCFU0 | 7.29 (2.4) |

| Maximum population size (log10 CFU/ml) | logCFUmax | 10.1 (1.1) |

| Replication rate constant (h−1) | k21 | 50 (fixed) |

| Mean generation time (min) | ||

| IPMS/TOBS | k12,SS−1 | 33.7 (9.9)c |

| IPMR/TOBI | k12,RI−1 | 63.2 (11.0) |

| IPMI/TOBR | k12,IR−1 | 33.7 (9.9)c |

| Log10 mutation frequencies at 0 h | ||

| IPM | logMUT,IPMb | −5.59 (4.9) |

| TOB | logMUT,TOB | −3.22 (7.8) |

| Killing by IPM | ||

| Maximum killing rate constant (h−1) | Kmax,IPM | 1.74 (19.0) |

| Imipenem concn causing 50% of Kmax,IPM (mg/liter) | ||

| IPMS/TOBS | KC50,SS,IPM | 0.175 (29.4) |

| IPMR/TOBI | KC50,RI,IPM | 645 (17.8) |

| IPMI/TOBR | KC50,IR,IPM | Monotherapy, 112 (17.9); combination (TOB ≥1.15 mg/liter), 1.60 (41.2) |

| Hill coefficient for imipenem | HILLIPM | 3.0 (fixed)d |

| Killing by TOB | ||

| Maximum killing rate constant (h−1) | ||

| IPMS/TOBS | Kmax,TOB,SS | 4.69 (14.7)e |

| IPMR/TOBI | Kmax,TOB,RI | 0.992 (9.5) |

| IPMI/TOBR | Kmax,TOB,IR | 4.69 (14.7)e |

| Tobramycin concn causing 50% of Kmax,TOB (mg/liter) | ||

| IPMS/TOBS | KC50,SS,TOB | 0.156 (49.4) |

| IPMR/TOBI | KC50,RI,TOB | 0.316 (25.6) |

| IPMI/TOBR | KC50,IR,TOB | 27.7 (10.7) |

| Tobramycin concn required for mechanistic synergy (mg/liter) | TOBcut | 1.15 (20.5) |

| SD of residual error on log10 scale | SDCFU | 0.304 (10.7) |

IPM, imipenem; TOB, tobramycin; S, susceptible; R, resistant; I, intermediate.

MUT, mutant.

Mean generation time (transition from state 1 to state 2) was assumed to be the same for the SS and IR populations. Estimation as separate values yielded no benefit.

It was beneficial to include a Hill coefficient for imipenem. Following a sensitivity analysis involving different Hill coefficient values, the Hill coefficient was fixed at 3.0.

The maximum rate of bacterial killing by tobramycin (Kmax,TOB) was assumed to be the same for the SS and IR population. Estimation as separate values yielded no benefit.

Validation of novel combination dosing strategies.

This study is the first to demonstrate that a rationally optimized imipenem-plus-tobramycin combination dosage regimen can achieve extensive (>5 log10) synergistic bacterial killing and suppress resistance of a CRAB isolate in the HFIM over 7 days. When combined with tobramycin, synergy was achieved by imipenem concentrations as low as 7.6 mg/liter (equivalent to 24% of the MIC of 32 mg/liter) in the dynamic in vitro HFIM system. This was in complete absence of an immune system. We further showed that translational predictions from MBM Monte Carlo simulations based on SCTK data were successfully validated in the HFIM (9). This MBM was subsequently refined to characterize the HFIM data.

Both tobramycin and the highest-studied imipenem concentration (23.3 mg/liter, 95th percentile) in monotherapy achieved slightly more than 3 log10 bacterial killing; however, this was followed by rapid and extensive emergence of high-level resistance in our CRAB isolate (Fig. 2). The proposed optimized combination dosage regimen achieved rapid and extensive bacterial killing with near-complete suppression of resistance (Fig. 2).

This combination regimen proved robust when we used the HFIM to simulate the median, 5th, and 95th percentiles of concentrations expected to occur in critically ill patients; the Monte Carlo simulations were performed for a continuous infusion of imipenem 4 g/day with a 1-g loading dose. In combination with tobramycin 7 mg/kg q24h, all three imipenem concentration-time profiles yielded synergistic killing and resistance suppression over 7 days even for patients with the 5th percentile of the imipenem (7.6 mg/liter) concentration.

For tobramycin 7 mg/kg q24h (as a 0.5-h infusion) against this CRAB isolate, the area under the unbound concentration-time curve over 24 h divided by the MIC (fAUC/MIC) was 51.5, and the free maximum unbound concentration over MIC (fCmax/MIC) was 8.9. Note that the unbound imipenem concentrations were below the MIC during the entire therapy (i.e., fT>MIC, 0%), even for the 95th percentile of imipenem concentrations arising from an imipenem 4-g continuous infusion with a 1-g loading dose. For this rationally optimized dosage regimen, the imipenem concentrations were 24% (7.6 mg/liter), 42% (13.4 mg/liter), and 73% (23.3 mg/liter) of the MIC (32 mg/liter); these concentrations achieved enhanced killing and resistance suppression in combination with tobramycin against this CRAB isolate.

In the past, low-inoculum checkerboard and SCTK studies showed synergy for imipenem plus tobramycin against A. baumannii isolates (25, 26); however, no study assessed this combination in the HFIM. Cefepime plus amikacin was studied in HFIM and murine models against CRAB (10, 12), but extensive regrowth occurred in the HFIM. Empirical, nonoptimized imipenem-plus-aminoglycoside combinations were studied at a single time point (i.e., 24 or 48 h) against CRAB in murine and guinea pig pneumonia models (11, 27, 28). The present prospective HFIM validation study evaluated bacterial killing, regrowth, and resistance in a CRAB isolate over 7 days.

A limitation of this study was the use of a single CRAB isolate that was assessed by translational MBM. We only studied one replicate of each dosage regimen, although the results were robust and consistent for our combinations, which used three imipenem concentrations. Our observed tobramycin concentrations fell within the range of concentrations found in critically ill patients (15). While it is a limitation of this study that imipenem concentrations were not measured, we precisely achieved the targeted imipenem concentrations after continuous infusions in previous HFIM studies. Tobramycin monotherapy failed, with rapid and extensive resistance at the studied high inoculum (Fig. 2B). Although we found extensive synergy against a tobramycin-susceptible CRAB isolate, synergy may be less pronounced or absent in tobramycin-resistant CRAB isolates. However, we previously showed in SCTK and a mouse thigh infection model that rationally optimized imipenem-plus-tobramycin combinations yielded extensive synergistic killing without resistance emergence in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate resistant to both imipenem (MIC, 16 mg/liter) and tobramycin (MIC, 32 mg/liter) (29, 30).

Moreover, the present study was not designed to identify the PK/pharmacodynamic index for tobramycin that best predicts outer membrane permeabilization. Future studies are required to investigate this question. The synergy mechanism proposed by our MBM is in agreement with electron micrographs of ultrastructural damage and loss of cytosolic green fluorescent protein from a P. aeruginosa strain (31); tobramycin 0.25 mg/liter disrupted the outer membrane of this P. aeruginosa strain, which was in the range of the estimate (1.15 mg/liter) in the present study.

We employed the latest MBM to describe the antibacterial effects of the imipenem and tobramycin concentration-time profiles in monotherapy and combination; the final model contained three preexisting bacterial populations of different susceptibility (Fig. S4; Table 1). Both subpopulation synergy and mechanistic synergy (i.e., tobramycin enhancing the outer membrane penetration of imipenem) were needed to adequately describe the HFIM data (32).

The outer membrane of A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa isolates presents a formidable penetration barrier (33–36), and its disruption may enhance the target site penetration of imipenem (9, 37–39). Mechanistic synergy in our model is supported by studies that demonstrated disruption of the outer membrane of P. aeruginosa by albumin-conjugated aminoglycosides (40, 41) and the outer membrane permeabilizing effect of aminoglycoside hybrid antibiotics (42, 43).

In our previous SCTK studies, imipenem 8 mg/liter achieved synergistic killing and resistance suppression in combination with tobramycin against the studied CRAB isolate, as observed in the HFIM (Fig. 2F) (9). Imipenem 4 g/day continuous infusion was predicted to achieve an unbound steady-state concentration of at least 7.6 mg/liter in 95% of Monte Carlo-simulated critically ill patients (9). For patients with low or intermediate imipenem clearance, slightly lower doses should be sufficient to achieve the desired imipenem exposure, especially if therapeutic drug management is employed (44, 45).

In summary, the proposed rationally optimized imipenem-plus-tobramycin combination dosage regimen demonstrated synergistic killing and suppressed resistance at clinically relevant exposure profiles of both antibiotics. This is the first study to report the prospective evaluation of an optimized combination regimen against a CRAB isolate in the HFIM over 7 days. Synergy was explained by tobramycin disrupting and thereby permeabilizing the outer membrane toward imipenem. Future animal infection models and ultimately clinical studies are warranted to evaluate this highly promising combination regimen, which was rationally optimized by translational mechanism-based modeling.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grants (APP1045105 to J.B.B., C.B.L., R.L.N., and J.D.B. and APP1101553 to C.B.L., J.B.B., and R.L.N.). The project reported here was partly supported by award R01AI130185 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (J.B.B. and J.D.B.).

R.Y. thanks the Australian Government, Monash Graduate Education for providing a Monash Graduate Scholarship and Research Training Program fees Offset Scholarship. C.B.L. is the recipient of an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1062509) and J.B.B. of an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship level 2 (APP1084163).

The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02053-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong D, Nielsen TB, Bonomo RA, Pantapalangkoor P, Luna B, Spellberg B. 2017. Clinical and pathophysiological overview of Acinetobacter infections: a century of challenges. Clin Microbiol Rev 30:409–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peleg AY, Hooper DC. 2010. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N Engl J Med 362:1804–1813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0904124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perez F, Hujer AM, Hujer KM, Decker BK, Rather PN, Bonomo RA. 2007. Global challenge of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3471–3484. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mera RM, Miller LA, Amrine-Madsen H, Sahm DF. 2010. Acinetobacter baumannii 2002-2008: increase of carbapenem-associated multiclass resistance in the United States. Microb Drug Resist 16:209–215. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2010.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frieden T. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milatovic D, Braveny I. 1987. Development of resistance during antibiotic therapy. Eur J Clin Microbiol 6:234–244. doi: 10.1007/BF02017607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peleg AY, Franklin C, Bell JM, Spelman DW. 2006. Emergence of carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii recovered from blood cultures in Australia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 27:759–761. doi: 10.1086/507012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav R, Landersdorfer CB, Nation RL, Boyce JD, Bulitta JB. 2015. Novel approach to optimize synergistic carbapenem-aminoglycoside combinations against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2286–2298. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04379-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim TP, Ledesma KR, Chang KT, Hou JG, Kwa AL, Nikolaou M, Quinn JP, Prince RA, Tam VH. 2008. Quantitative assessment of combination antimicrobial therapy against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:2898–2904. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01309-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montero A, Ariza J, Corbella X, Domenech A, Cabellos C, Ayats J, Tubau F, Borraz C, Gudiol F. 2004. Antibiotic combinations for serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a mouse pneumonia model. J Antimicrob Chemother 54:1085–1091. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan Z, Ledesma KR, Singh R, Hou J, Prince RA, Tam VH. 2010. Quantitative assessment of combination antimicrobial therapy against multidrug-resistant bacteria in a murine pneumonia model. J Infect Dis 201:889–897. doi: 10.1086/651024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicasio AM, Bulitta JB, Lodise TP, D'Hondt RE, Kulawy R, Louie A, Drusano GL. 2012. Evaluation of once-daily vancomycin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a hollow-fiber infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:682–686. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05664-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuji BT, Bulitta JB, Brown T, Forrest A, Kelchlin PA, Holden PN, Peloquin CA, Skerlos L, Hanna D. 2012. Pharmacodynamics of early, high-dose linezolid against vancomycin-resistant enterococci with elevated MICs and pre-existing genetic mutations. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2182–2190. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conil JM, Georges B, Ruiz S, Rival T, Seguin T, Cougot P, Fourcade O, Houin G, Saivin S. 2011. Tobramycin disposition in ICU patients receiving a once daily regimen: population approach and dosage simulations. Br J Clin Pharmacol 71:61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakka SG, Glauner AK, Bulitta JB, Kinzig-Schippers M, Pfister W, Drusano GL, Sorgel F. 2007. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of continuous versus short-term infusion of imipenem-cilastatin in critically ill patients in a randomized, controlled trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3304–3310. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01318-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konig C, Simmen HP, Blaser J. 1998. Bacterial concentrations in pus and infected peritoneal fluid–implications for bactericidal activity of antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 42:227–232. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S, Kwon KT, Kim HI, Chang HH, Lee JM, Choe PG, Park WB, Kim NJ, Oh MD, Song DY, Kim SW. 2014. Clinical implications of cefazolin inoculum effect and b-lactamase type on methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Microb Drug Resist 20:568–574. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drusano GL, Corrado ML, Girardi G, Ellis-Grosse EJ, Wunderink RG, Donnelly H, Leeper KV, Brown M, Malek T, Hite RD, Ferrari M, Djureinovic D, Kollef MH, Mayfield L, Doyle A, Chastre J, Combes A, Walsh TJ, Dorizas K, Alnuaimat H, Morgan BE, Rello J, Torre CAM, Jones RN, Flamm RK, Woosley L, Ambrose PG, Bhavnani S, Rubino CM, Bulik CC, Louie A, Vicchiarelli M, Berman C. 2018. Dilution factor of quantitative bacterial cultures obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage in patients with ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:pii=e01323-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01323-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer RJ, Guzy S, Ng C. 2007. A survey of population analysis methods and software for complex pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic models with examples. AAPS J 9:E60–E83. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0901007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulitta JB, Landersdorfer CB. 2011. Performance and robustness of the Monte Carlo importance sampling algorithm using parallelized S-ADAPT for basic and complex mechanistic models. AAPS J 13:212–226. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bulitta JB, Bingolbali A, Shin BS, Landersdorfer CB. 2011. Development of a new pre- and post-processing tool (SADAPT-TRAN) for nonlinear mixed-effects modeling in S-ADAPT. AAPS J 13:201–211. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9257-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bulitta JB, Duffull SB, Kinzig-Schippers M, Holzgrabe U, Stephan U, Drusano GL, Sorgel F. 2007. Systematic comparison of the population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperacillin in cystic fibrosis patients and healthy volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:2497–2507. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01477-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuji BT, Okusanya OO, Bulitta JB, Forrest A, Bhavnani SM, Fernandez PB, Ambrose PG. 2011. Application of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling and the justification of a novel fusidic acid dosing regimen: raising Lazarus from the dead. Clin Infect Dis 52(Suppl 7):S513–S519. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marques MB, Brookings ES, Moser SA, Sonke PB, Waites KB. 1997. Comparative in vitro antimicrobial susceptibilities of nosocomial isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii and synergistic activities of nine antimicrobial combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:881–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sung H, Choi SJ, Yoo S, Kim MN. 2007. In vitro antimicrobial synergy against imipenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Korean J Lab Med 27:111–117. (In Korean.) doi: 10.3343/kjlm.2007.27.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernabeu-Wittel M, Pichardo C, Garcia-Curiel A, Pachon-Ibanez ME, Ibanez-Martinez J, Jimenez-Mejias ME, Pachon J. 2005. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic assessment of the in vivo efficacy of imipenem alone or in combination with amikacin for the treatment of experimental multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect 11:319–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez-Hernandez MJ, Pachon J, Pichardo C, Cuberos L, Ibanez-Martinez J, Garcia-Curiel A, Caballero FJ, Moreno I, Jimenez-Mejias ME. 2000. Imipenem, doxycycline and amikacin in monotherapy and in combination in Acinetobacter baumannii experimental pneumonia. J Antimicrob Chemother 45:493–501. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadav R, Bulitta JB, Nation RL, Landersdorfer CB. 2017. Optimization of synergistic combination regimens against carbapenem- and aminoglycoside-resistant clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates via mechanism-based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01011-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yadav R, Bulitta JB, Wang J, Nation RL, Landersdorfer CB.. 2017. Evaluation of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model-based optimized combination regimens against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a murine thigh infection model by using humanized dosing schemes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:pii=e01268-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yadav R, Bulitta JB, Schneider EK, Shin BS, Velkov T, Nation RL, Landersdorfer CB.. 2017. Aminoglycoside concentrations required for synergy with carbapenems against Pseudomonas aeruginosa determined via mechanistic studies and modeling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:pii=e00722-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landersdorfer CB, Ly NS, Xu H, Tsuji BT, Bulitta JB. 2013. Quantifying subpopulation synergy for antibiotic combinations via mechanism-based modeling and a sequential dosing design. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2343–2351. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00092-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obara M, Nakae T. 1991. Mechanisms of resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Antimicrob Chemother 28:791–800. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.6.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato K, Nakae T. 1991. Outer membrane permeability of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and its implication in antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 28:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakaye B, Dubus A, Joris B, Frere JM. 2002. Method for estimation of low outer membrane permeability to beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:2901–2907. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2901-2907.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugawara E, Nikaido H. 2012. OmpA is the principal nonspecific slow porin of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Bacteriol 194:4089–4096. doi: 10.1128/JB.00435-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulitta JB, Ly NS, Landersdorfer CB, Wanigaratne NA, Velkov T, Yadav R, Oliver A, Martin L, Shin BS, Forrest A, Tsuji BT. 2015. Two mechanisms of killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by tobramycin assessed at multiple inocula via mechanism-based modeling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2315–2327. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04099-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yadav R, Bulitta JB, Schneider EK, Shin BS, Velkov T, Nation RL, Landersdorfer CB. 2017. Aminoglycoside concentrations required for synergy with carbapenems against Pseudomonas aeruginosa determined via mechanistic studies and modeling. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:pii=e00722-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00722-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yadav R, Bulitta JB, Wang J, Nation RL, Landersdorfer CB. 2017. Evaluation of pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model-based optimized combination regimens against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a murine thigh infection model using humanized dosing schemes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:pii=e01268-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01268-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kadurugamuwa JL, Clarke AJ, Beveridge TJ. 1993. Surface action of gentamicin on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 175:5798–5805. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5798-5805.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadurugamuwa JL, Lam JS, Beveridge TJ. 1993. Interaction of gentamicin with the A band and B band lipopolysaccharides of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its possible lethal effect. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 37:715–721. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.4.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorityala BK, Guchhait G, Fernando DM, Deo S, McKenna SA, Zhanel GG, Kumar A, Schweizer F. 2016. Adjuvants based on hybrid antibiotics overcome resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and enhance fluoroquinolone efficacy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 55:555–559. doi: 10.1002/anie.201508330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gorityala BK, Guchhait G, Goswami S, Fernando DM, Kumar A, Zhanel GG, Schweizer F. 2016. Hybrid antibiotic overcomes resistance in P. aeruginosa by enhancing outer membrane penetration and reducing efflux. J Med Chem 59:8441–8455. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel BM, Paratz J, See NC, Muller MJ, Rudd M, Paterson D, Briscoe SE, Ungerer J, McWhinney BC, Lipman J, Roberts JA. 2012. Therapeutic drug monitoring of beta-lactam antibiotics in burns patients–a one-year prospective study. Ther Drug Monit 34:160–164. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31824981a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pea F, Cojutti P, Sbrojavacca R, Cadeo B, Cristini F, Bulfoni A, Furlanut M. 2011. TDM-guided therapy with daptomycin and meropenem in a morbidly obese, critically ill patient. Ann Pharmacother 45:e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.