ABSTRACT

The outer membrane is an essential structural component of Gram-negative bacteria that is composed of lipoproteins, lipopolysaccharides, phospholipids, and integral β-barrel membrane proteins. A dedicated machinery, called the Lol system, ensures proper trafficking of lipoproteins from the inner to the outer membrane. The LolCDE ABC transporter is the inner membrane component, which is essential for bacterial viability. Here, we report a novel pyrrolopyrimidinedione compound, G0507, which was identified in a phenotypic screen for inhibitors of Escherichia coli growth followed by selection of compounds that induced the extracytoplasmic σE stress response. Mutations in lolC, lolD, and lolE conferred resistance to G0507, suggesting LolCDE as its molecular target. Treatment of E. coli cells with G0507 resulted in accumulation of fully processed Lpp, an outer membrane lipoprotein, in the inner membrane. Using purified protein complexes, we found that G0507 binds to LolCDE and stimulates its ATPase activity. G0507 still binds to LolCDE harboring a Q258K substitution in LolC (LolCQ258K), which confers high-level resistance to G0507 in vivo but no longer stimulates ATPase activity. Our work demonstrates that G0507 has significant promise as a chemical probe to dissect lipoprotein trafficking in Gram-negative bacteria.

KEYWORDS: LolCDE, antibiotic discovery, lipoprotein trafficking, outer membrane biogenesis, phenotypic assay, stress response

INTRODUCTION

The outer membrane (OM) is an essential structural component of Gram-negative bacteria that provides a robust permeability barrier against a wide variety of xenobiotics while allowing the diffusion of necessary nutrients (1). This barrier is an asymmetrical lipid bilayer composed of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the outer leaflet and phospholipids in the inner leaflet (2) with integral β-barrel OM proteins (OMPs) as well as OM lipoproteins. Proteins in the OM not only are important for maintaining the structural integrity of the OM but also play important roles in several aspects of bacterial physiology such as nutrient and protein translocation, adhesion, and signal transduction (1).

The unique components of the OM, specifically LPS, OMPs, and lipoproteins, are each processed and transported by dedicated, multiprotein pathways that are essential for bacterial survival (3). LPS is synthesized by several essential cytoplasmic enzymes, flipped to the periplasm by the essential inner membrane protein MsbA, and transported to its OM location by the essential Lpt system (4–6). Multiple components of this process have been explored as therapeutic targets (7, 8). Folding and insertion of OMPs is catalyzed by the β-barrel assembly (BAM) machinery which contains two essential proteins: BamA and BamD (9, 10). There is evidence of possible therapeutic intervention in this process as well (11). Finally, OM lipoprotein maturation and transport involve eight essential extracytoplasmic proteins, Lgt, LspA, and Lnt, which are integral membrane proteins embedded in the inner membrane and function sequentially to produce mature triacylated lipoproteins (12). A five-protein LolABCDE then traffics OM-destined lipoproteins to the OM (12). Inhibitors of LolCDE were identified in phenotypic screens for inhibition of growth of a permeabilized Escherichia coli strain (13) and for induction of the AmpC β-lactamase reporter (14).

LolCDE form an inner membrane ABC transporter that releases mature lipoproteins from the inner membrane to LolA, which shuttles lipoproteins across the periplasm to LolB, itself an OM lipoprotein, which catalyzes their insertion into the OM (15). Recently, it has been demonstrated that there is an alternate trafficking system that still utilizes LolCDE for the recognition and extraction of lipoproteins from the inner membrane but delivers lipoproteins to the OM via a LolA- and LolB-independent mechanism (16).

The attractiveness of OM biogenesis processes as antibacterial targets is driven in particular by their essentiality, conservation, and extracytoplasmic localization. The ability to identify new chemical matter that specifically targets the processes involved in OM biogenesis thus could provide promising new antibacterial leads and tool compounds that help dissect essential pathways in OM biogenesis. In E. coli and related gammaproteobacteria, the alternative sigma factor σE is induced by stresses that disrupt the integrity of the OM (17). Mutations and inhibitors that inhibit steps in OM biogenesis were shown to activate the σE stress response (18, 19). Here, we report the identification of a novel pyrrolopyrimidinedione compound, G0507, which was identified in a phenotypic screen for inhibitors of E. coli growth, followed by selection of compounds that induced the extracytoplasmic σE stress response. Using various genetic and biochemical assays, we demonstrate that G0507 is an inhibitor of LolCDE. G0507 will be a valuable tool to further interrogate OM lipoprotein maturation and trafficking as a target for the development of antimicrobial agents against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

RESULTS

G0507 is a novel inhibitor of Gram-negative E. coli growth, and mutations in lolCDE genes abrogate the effect of G0507.

G0507 was identified by a phenotypic screen, as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, a primary screen was conducted on a collection of 35,000 structurally diverse synthetic molecules to identify compounds that inhibited the growth of an efflux-deficient (ΔtolC) and an OM-compromised (imp4213) laboratory strain of E. coli MG1655. In a second step, hits from the primary assay were tested for their ability to induce the σE response in an eight-point dose-response assay using a ΔtolC strain harboring the rpoHP3-lacZ reporter (17). G0507 is a pyrrolopyrimidinedione compound (Fig. 1A) with MIC values of 0.5 and 1 μg/ml against the ΔtolC and imp4213 strains, respectively. G0507 activated the σE stress response in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B and C). G0507 was inactive against the wild-type E. coli MG1655 strain and showed no activity against Staphylococcus aureus USA300 (MIC > 64 μg/ml).

FIG 1.

Novel compound inhibits the growth of E. coli and induces the σE stress response. (A) Chemical structure of G0507. (B and C) Induction of the σE stress response by G0507. The σE reporter strain (MG1655 Δlac attB::rpoHP3-lacZ tolC::aph; GNEID1222) was incubated with G0507 ranging from 0 to 100 μM for 4 h (B) or with 3.1 μM G0507 for 0 to 4 h (C). β-Galactosidase activity (measured by Beta-Glo assay reagent) was normalized for cell numbers by dividing activity by the BacTiter-Glo activity, yielding normalized β-galactosidase activity. σE induction equals normalized β-galactosidase activity in the presence of compound divided by normalized β-galactosidase activity in the presence of DMSO. The dotted line shows the level of σE activity in the absence of G0507. Error bars represent the standard deviations of triplicate samples.

To determine the molecular target, we selected for mutants resistant to G0507 at 4× MIC using the E. coli imp4213 strain. Mutants resistant to G0507 appeared with a frequency of 3.3 × 10−8. Similar values were obtained at 8× and 16× MIC (2.6 × 10−8 and 1.6 × 10−8, respectively). Whole-genome sequencing of 10 independent isolates revealed that each of the isolates had a single nonsynonymous point mutation in lolC, lolD, or lolE. This result suggests that at least seven unique amino acid substitutions in LolC, LolD, and LolE proteins are able to confer resistance to G0507 (Fig. 2). For each of the genes in the lolCDE operon, we selected a representative mutant, LolC with a Q258K change (LolCQ258K), LolDP164S, or LolEL371P, and measured its G0507 MIC (Table 1). All three mutants showed high-level resistance to G0507, i.e., a MIC increase of ≥64-fold compared to that of the parental imp4213 strain, but remained susceptible to other classes of antibiotics, including globomycin, a cyclic pentapeptide antibiotic that inhibits the second reaction of the three-step posttranslational lipid modification (20) (Table 1).

FIG 2.

Mutations conferring resistance to G0507 localized to the LolCDE ABC transporter. Topology models for LolC and LolE are based on Yasuda et al. (44). Mutations identified by whole-genome sequencing are highlighted in bold, while the remaining mutations were identified by sequencing the lolCDE operon of additional resistant mutants.

TABLE 1.

MICs of E. coli imp4213 and isolates resistant to antimicrobial compounds

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli imp4213 | E. coli imp4213_LolCQ258K | E. coli imp4213_LolDP164S | E. coli imp4213_LolEL371P | |

| Vancomycin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Rifampin | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 |

| Erythromycin | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.0078 | 0.0078 | 0.0078 | 0.0078 |

| Bacitracin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tetracycline | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Chloramphenicol | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Globomycin | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 |

| G0507 | 1 | >64 | >64 | >64 |

MICs were determined by microdilution (40).

G0507 causes morphological changes indicative of defects in the lipoprotein maturation/transport pathway.

Inhibition of lipoprotein maturation and transport has been shown to lead to characteristic morphological changes, including swelling of the periplasmic space at the bacterial poles (13). To determine whether G0507 causes similar morphological changes, E. coli imp4213 bacteria were treated with 4× MIC of G0507 for 2 h and then subjected to fluorescence microscopy. To visualize membranes and DNA, cells were stained with the membrane dye Nile red and the fluorescent DNA-intercalating agent 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) prior to microscopy. G0507-treated cells displayed noticeable swelling of the periplasmic space, with intense membrane staining at the poles, similar to cells treated with globomycin (Fig. 3). This result supports the hypothesis that G0507 is an inhibitor of the lipoprotein maturation and transport pathways.

FIG 3.

G0507 causes morphological changes in cells similar to those with treatment with globomycin. MG1655 imp4213 cells in the exponential phase of growth were treated with G0507 and globomycin at 4× MIC for 2 h. Cells were harvested and prepared for confocal microscopy. Cells were stained with the membrane dye Nile Red (red) to visualize membranes and the DNA-intercalating agent DAPI (blue) to label DNA. Images were acquired using confocal fluorescence microscopy at ×100 magnification. Bar, 1 μm.

Deletion of Lpp is a mechanism of resistance against G0507.

In order to understand whether mutations in lolCDE are the only mechanisms to confer resistance to G0507, we sequenced the lolCDE operons of 24 additional mutants resistant to G0507. Nineteen isolates had a single mutation in the lolCDE operon (Fig. 2 and 4), while a further five maintained wild-type lolCDE (Fig. 4). Whole-genome sequencing of the latter group of strains revealed that four of the five mutants had either a genomic deletion encompassing lpp or an insertion in the spacer region between lpp and its promoter (Fig. 4). The lpp gene encodes the most abundant E. coli OM lipoprotein, Lpp, also referred to as Braun's lipoprotein (21). Inhibition of Lpp processing and transport leads to toxic covalent adducts between peptidoglycan and Lpp trapped in the inner membrane, and this toxicity can be alleviated by deletion of Lpp (22). This suggested that the identified mutations affecting lpp confer resistance to G0507 by blocking Lpp expression. Consistent with this hypothesis, all four mutants lost Lpp production, as seen by Western blotting with Lpp-specific antibodies (Fig. 4). Targeted deletion of Lpp resulted in a similar degree of G0507 resistance (MIC for the ΔtolC Δlpp strain [MICΔtolC Δlpp] of >64 μg/ml versus MICΔtolC of 0.5 μg/ml). One mutant had a single nucleotide change in the lpp gene resulting in an amino acid substitution, from a glycine to an aspartate, at position 14 of the Lpp protein (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the LppG14D mutant still produced Lpp, most of which migrated as dimers in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4). An LppG14D substitution was previously found to confer resistance to globomycin (23–25). The glycine-to-aspartate change prevents correct lipoprotein processing; however, the mechanism by which this mutation confers resistance to either G0507 or globomycin remains unclear.

FIG 4.

Loss of Lpp confers resistance to G0507. The schematic represents 24 individual resistance mutants selected against 4× MIC G0507. Nineteen resistant mutants had mutations in lolC, lolD, or lolE. The five remaining mutants with wild-type lolCDE genes had mutations upstream of or in the lpp gene, identified by whole-genome sequencing. Immunoblotting with Lpp-specific polyclonal antibodies shows that four mutants lost expression of Lpp (inset).

G0507 causes retention of Lpp in the inner membrane.

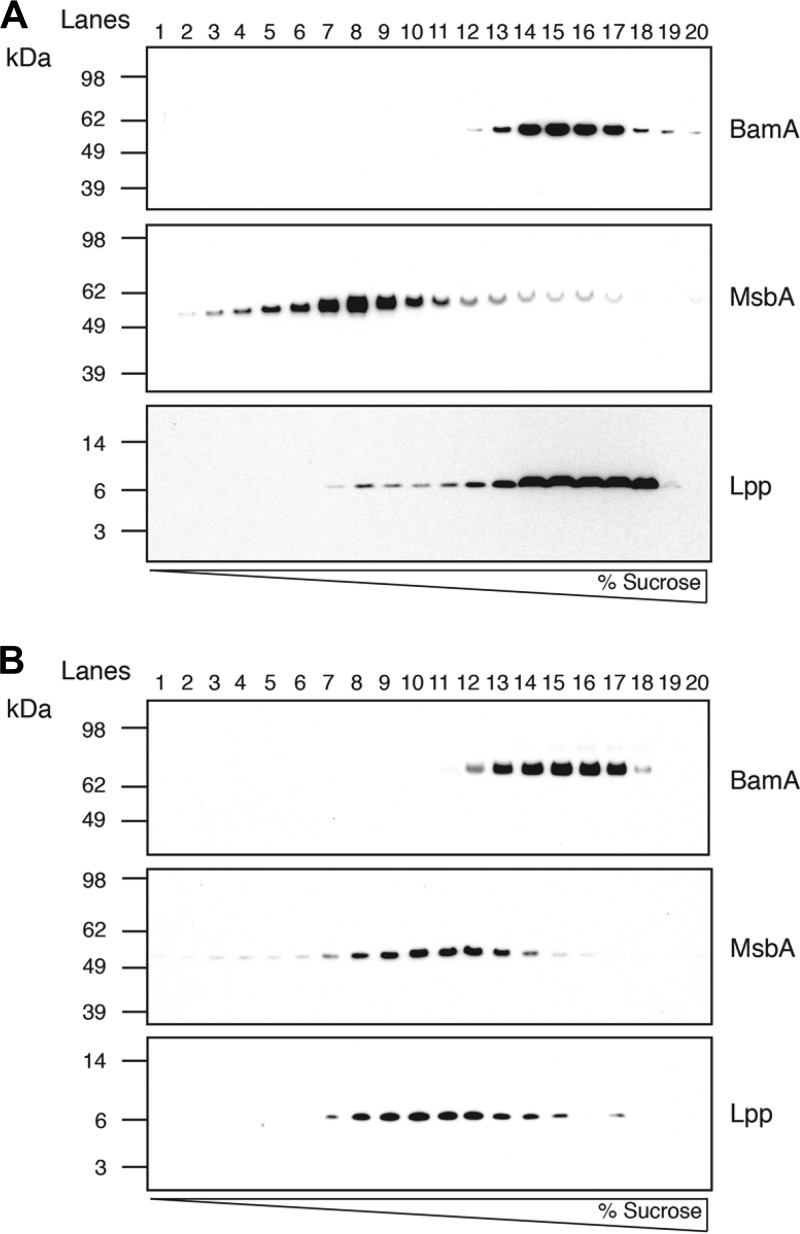

In order to obtain direct evidence that G0507 blocks lipoprotein trafficking from the inner to the outer membrane, we studied the localization of Lpp in G0507-treated cells. To allow monitoring of newly synthesized Lpp, His-tagged Lpp lacking the C-terminal lysine residue (LppΔK58) was expressed from an arabinose-inducible promoter in one of the previously described resistance mutants, which does not produce its endogenous Lpp (GNEID4177 strain) (Table 2). The C-terminal lysine was shown to be required for covalent linkage to the peptidoglycan (21). Total membranes prepared from G0507-treated and untreated cells were subjected to sucrose density gradient centrifugation (Fig. 5A and B). The inner membrane protein MsbA and the outer membrane protein BamA were used as markers for the inner and outer membranes, respectively. The majority of Lpp in untreated cells was present in fractions in which BamA was present, while Lpp in G0507-treated cells appeared in earlier fractions in which the majority of MsbA was present (Fig. 5A and B). This result clearly indicates that G0507 prevents the transport of lipoproteins to the OM and leads to accumulation of Lpp in the inner membrane.

TABLE 2.

Strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| TOP10 | F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) ϕ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG | ThermoFisher Scientific |

| MG1655 | ATCC 700926; F− lambda− ilvG-rfb-50 rph1 | ATCC |

| BW25113 | lacIq rrnBT14 ΔlacZWJ16 hsdR514 ΔaraBADAH33 ΔrhaBADLD78 | 38 |

| BW tolC | BW25113 tolC::aph; Kanr | 45 |

| GNEID0031 | MG1655 tolC::aph; Kanr | In-house strain |

| GNEID0016 | MG1655 imp4213::aph; Kanr | In-house strain |

| GNEID0092 | MG1655 lptD::aph attB::PBAD-lptD; Kanr, Ampr | In-house strain |

| GNEID0142 | MG1655 bamA101 (EZ-Tn5 insertion 23 bp upstream of the AUG start codon of the bamA gene with a 9-bp chromosomal duplication) | 10 |

| GNEID3536 | MG1655 msbA::aph attB::PBAD-msbA; Kanr, Ampr | In-house strain |

| GNEID1167 | MG1655 lacZYA::aph; Kanr | This study |

| GNEID1179 | MG1655 lacZYA | This study |

| GNEID1183 | MG1655 lacZYA attB::rpoHP3_lacZ; Ampr | This study |

| GNEID1187 | MG1655 lacZYA attB::rpoHP3_rbs-lacZ; Ampr | This study |

| GNEID1222 | MG1655 lacZYA attB::rpoHP3_rbs-lacZ tolC::aph; Kanr, Ampr | This study |

| GNEID4270 | MG1655 tolC lpp::aph; Kanr | This study |

| GNEID4177 | MG1655 tolC::aph lpp (mutant strain 4 that has lost expression of Lpp) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | Cloning vector; Cmr, Tetr | New England Biolabs |

| pBAD24 | Expression vector with arabinose-inducible promoter; Ampr | 46 |

| pCDF-Duet-1 | Expression vector; Strr | Novagen |

| pRSF-Duet-1 | Expression vector; Kanr | Novagen |

| pKD4 | Source of FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance cassette; Ampr | 38 |

| pKD13 | Source of FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance cassette; Ampr | 38 |

| pSIM18 | λ Red recombinase helper plasmid; Hygr | 39 |

| pCP20 | Source of Flp recombinase, temperature-sensitive replicon; Ampr | 38 |

| pLDR9 | Cloning vector for integration into the λ attachment site attB; Ampr, Kanr | 37 |

| pLDR8 | Temperature-sensitive vector expressing lambda integrase | 37 |

| pGNE6 | pLDR9 + rpoHP3_lacZ | This study |

| pGNE7 | pLDR9 + rpoHP3_rbs-lacZ | This study |

| pGNE18 | pACYC184 + rpoHP3-rbs-lacZ | This study |

| pGNE68 | pBAD24 + lpp | This study |

| pGNE69 | pBAD24 + lppΔK58-6×His tag | This study |

| p770999 | pCDF-Duet-1 + lolCD-TEV-8×His tag | This study |

| p771003 | pRSF-Duet-1 + lolE-TEV-Strep tag | This study |

Amp, ampicillin; Kan, kanamycin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Tet, tetracycline; Hyg, hygromycin; Strep, streptomycin.

FIG 5.

Accumulation of Lpp in the inner membrane of cells treated with G0507. Total membranes from untreated cells (A) and cells treated with G0507 (B) were separated by floatation sucrose density gradient centrifugation, followed by fractionation into 20 fractions from the top (35% sucrose) to the bottom (58% sucrose) of the gradient. Each fraction was subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using polyclonal antibodies against BamA, MsbA, and Lpp, as indicated. MsbA is a control protein for inner membrane localization, and BamA is a control protein for outer membrane localization.

The Lpp protein is fully processed in E. coli cells treated with G0507.

The fact that mutations in the lolCDE operon cause resistance to G0507 suggests that G0507 is an inhibitor of LolCDE. However, the cellular phenotypes observed after G0507 treatment could also be caused by inhibitors disrupting an earlier step in the lipoprotein maturation and transport pathways (Fig. 3 and 5). The mutations in the lolCDE genes that rendered the E. coli cells resistant to G0507 could be on-target mutations that either directly interfere with the binding of G0507 to LolCDE or compensate for reduced LolCDE activity resulting from G0507 binding to another site of LolCDE. They could also be off-target mutations that alter the substrate specificity of LolCDE, enabling the complex to recognize and extract immature lipoproteins from the inner membrane. In the latter case, the primary target of G0507 would be an upstream protein in the lipoprotein maturation pathway. In order to distinguish between these two possibilities, we analyzed the Lpp protein that accumulates in G0507-treated cells. If G0507 is an inhibitor of LolCDE, the Lpp protein should be fully processed, with the same molecular mass as Lpp isolated from untreated bacteria (Fig. 6A). If G0507 targets a protein(s) upstream of LolCDE, the Lpp intermediates are expected to exhibit different molecular weights and mobilities on SDS-PAGE gels depending on the presence or absence of the signal peptide and the number of attached acyl chains (Fig. 6A). In order to facilitate the analysis, we used an MG1655 ΔtolC strain in which the endogenous lpp gene was deleted and expressed His-tagged LppΔK58, which cannot be covalently linked to the peptidoglycan (21). LppΔK58 isolated from G0507-treated cells migrated indistinguishably from Lpp isolated from untreated cells (Fig. 6B). Intact protein mass analysis by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) revealed that the LppΔK58 protein isolated from G0507-treated cells resulted in two distinctive peaks with calculated masses of 7,867.2 Da and 7,895.0 Da, which were comparable to those obtained from untreated cells (7,867.1 Da and 7,894.9 Da). Slight deviations from the expected mass for a fully processed, mature LppΔK58 protein (7,879 Da) might reflect some posttranslational modification of the LppΔK58 protein. Nevertheless, the fact that the LppΔK58 protein isolated from G0507-treated cells showed the same molecular mass as that from untreated cells equivocally demonstrates that the LppΔK58 protein isolated from G0507-treated cells is fully processed and that G0507 does not interfere with the lipoprotein maturation processes that are upstream of LolCDE. The LppΔK58 protein isolated from cells treated with 4× MIC of globomycin migrated more slowly in SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 6B) and displayed higher molecular masses in the mass spectrometry analysis than the fully processed protein (9,567.2 Da and 9,599.0 Da). This is consistent with the fact that globomycin inhibits LspA, resulting in the accumulation of lipoproteins with uncleaved signal peptides (Fig. 6A). Our results exclude the possibility that G0507 inhibits a step upstream of LolCDE. Therefore, G0507 does not interfere with the lipoprotein maturation processes, and its primary target is LolCDE.

FIG 6.

Accumulated Lpp in the inner membrane of G0507-treated cells is fully processed. (A) Schematic depicting the lipoprotein modification and transport pathway showing each step of the process and the expected mass of Lpp intermediates. (B) LppΔK58-6×His was expressed in a strain lacking endogenous Lpp (GNEID4177) and treated with 4× MIC of G0507 or globomycin for 1 h. Total cell lysates were subsequently separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with Lpp-specific polyclonal antibodies.

G0507 stimulates the basal ATPase activity of wild-type LolCDE, while a LolCQ258K substitution abrogates this effect.

LolCDE is an ABC transporter that uses energy derived from hydrolysis of ATP to drive lipoprotein transport (15). To better understand how G0507 inhibits LolCDE function and how mutations in LolCDE confer resistance to G0507, we recombinantly produced wild-type LolCDE (LolCDEWT) and an LolCDE complex harboring a point mutation in LolCQ258K (here referred to as LolCQ258KDE), which led to high-level resistance to G0507 in vivo (Table 1). Proteins were purified in the presence of detergent and reconstituted in amphipol A8-35. Amphipol-reconstituted LolCDEWT and LolCQ258KDE had comparable Km and kcat values (for LolCDEWT, Km = 176 ± 45 μM and kcat = 0.22 ± 0.02 s−1; for LolCQ258KDE, Km = 163 ± 45 μM and kcat = 0.19 ± 0.02 s−1), suggesting that the LolCQ258K substitution does not affect the basal ATPase activity of LolCDE. Moreover, both protein complexes were inhibited by ortho-vanadate with similar 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) (LolCDEWT, 20.9 ± 1.7 μM; LolCQ258KDE, 36.4 ± 1.8 μM). However, there was a noticeable difference in the ability of G0507 in stimulating the basal LolCDE ATPase activity. While the ATPase activity of LolCDEWT was clearly stimulated by G0507, G0507 had only a minor effect on the ATPase activity of LolCQ258KDE (Fig. 7). A surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiment revealed that G0507 binds to LolCDEWT and LolCQ258KDE complexes with comparable affinities with approximate KD values of 1.4 ± 0.5 μM and 0.8 ± 0.3 μM, respectively. Future work will shed light on the detailed mechanism of G0507 interaction with LolCDE and whether the observed stimulatory effect of G0507 on the LolCDE ATPase activity in vitro is responsible for the inhibition of LolCDE function in vivo.

FIG 7.

G0507 stimulates ATPase activity in wild-type LolCDE but not the mutant ABC transporter. The graph shows the changes in the ATPase activity (see Materials and Methods for details of the ATPase assay) of LolCDEWT and LolCQ258KDE in the presence of 0.8 μM and 3.2 μM G0507. Error bars represent standard deviations of duplicate samples from three independent experiments. In all experiments, LolCDEWT and LolCQ258KDE proteins were used at 10 nM.

DISCUSSION

The emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens is threatening the clinical efficacy of available antibiotics (26, 27). There is an urgent need for antibacterial compounds that act on novel targets to circumvent these emerging resistance mechanisms. The proteins involved in Gram-negative bacterial OM biogenesis are attractive potential targets due to the fact that many of them are essential for bacterial survival and are localized extracytoplasmically, thus negating the problems associated with penetrance through the inner membrane. A lack of robust biochemical assays for the processes associated with OM biogenesis might be one reason for the absence of inhibitors of this process. A phenotypic screen interrogating several different OM biogenesis pathways has the potential to not only identify novel inhibitors but also reveal new druggable targets which have traditionally not been amenable to screening in a cell-free system due to challenges in developing suitable assays.

Several phenotypes are associated with defective OM assembly (2). A prototypical phenotype is the increased sensitivity to xenobiotics (28). A recent phenotypic screen that used induction of the AmpC β-lactamase, indicative of peptidoglycan damage, as its readout successfully identified inhibitors of LolCDE and LpxH (14). LpxH catalyzes the fourth step in the biosynthesis of lipid A, the lipid component of LPS (29). Here, we used the induction of the σE stress response as a means to triage E. coli active hits in order to enrich for potential OM biogenesis inhibitors. The σE stress response is universally induced when different pathways involved in OM biosynthesis, such as lipoprotein, LPS, OMP synthesis, and transport pathways, are inhibited (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material). In addition to OM biogenesis inhibitors, the σE stress response is induced by inhibitors of cell wall biogenesis such as fosfomycin and the β-lactam antibiotics cefoxitin and ceftazidime (Fig. S1B). This result corroborates previous findings that OM and cell wall biogenesis are tightly connected (14, 30, 31). Moreover, the σE response was induced by polycationic compounds, including polymyxin B (PMB) and its derivative polymyxin B nonapeptide (PMBN), as well as aminoglycosides, such as amikacin and neomycin (Fig. S1B). Polycationic compounds compromise the OM integrity through competing with the stabilizing divalent cations for the interaction with the anionic LPS components (32). Inhibition of DNA synthesis (ciprofloxacin), protein synthesis (tetracycline), and protein translation (chloramphenicol) did not result in induction of the σE stress response (Fig. S1B). Deletion of tolC, as found in our screening strain (see Materials and Methods), had a minimal effect on the basal level of σE (Fig. S1A).

In addition to σE, four other extracytoplasmic stress responses are known in E. coli: the phage shock protein (Psp) pathway, which is induced by regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP) similar to σE; the phosphorelay signaling pathway system Rcs; and the two-component regulator systems CpxA/R and BaeS/R (33, 34). Although each system appears to be specialized in monitoring specific aspects of envelope biogenesis and maintenance, there is cross talk among different pathways, and an individual stimulus can lead to the induction of more than one pathway (34). Indeed, a previously described inhibitor of LolCDE was shown to induce the extracytoplasmic stress responses CpxA/R and Rcs simultaneously; induction of σE was not observed, likely due to the short 30-min exposure time to the inhibitor (35). Similarly, we observed noticeable induction of CpxA/R, Rcs, and BaeS/R stress responses by G0507 after 30 min of incubation (data not shown), while significant induction of the σE stress response by G0507 was observed only after prolonged incubation (Fig. 1C).

Although G0507 did not demonstrate a measurable MIC for the wild-type MG1655 strain (MIC > 64 μg/ml), medicinal chemistry optimization might lead to compounds with improved wild-type activity. Data from the limited number of G0507 analogs that were commercially available indicate that modification of the thiophene ring at the right-hand side is tolerated (Fig. 8). Indeed, one of the analogs, G0793, had a MIC value of 16 μg/ml against the wild-type MG1655 strain (Fig. 8). G0793 also showed weak activity against the EDTA-treated OM-permeabilized Enterobacter aerogenes strain ATCC 13048, while no activity was observed against the EDTA-treated OM-permeabilized Klebsiella pneumonia ATCC 43816 strain (Fig. 8). G0507 did not exhibit any activity against these two OM-permeabilized Enterobacteriaceae strains (Fig. 8). The resistance profile of G0793 was comparable to that of G0507, i.e., emergence of high-level resistance mutants even at 16× the MIC (data not shown). G0507 and the pyridine-imidazole compound 2, which is a recently identified inhibitor of LolCDE, are structurally dissimilar yet share similar resistance profiles (13), implying that the ability to generate high-level resistance mutants may be a common property of the LolCDE complex. Therefore, while G0507 will be a valuable tool to dissect lipoprotein trafficking in Gram-negative bacteria, G0507 and its structural analogs will unlikely be a candidate for lead optimization.

FIG 8.

Analogs of G0507 gain wild-type activity. Structures and MIC values (μg/ml) of G0507 and its analogs are shown. MICs were determined against E. coli wild-type MG1655 and imp4213 and ΔtolC strains, Gram-positive S. aureus USA300, and OM-permeabilized E. aerogenes strain ATCC 13048 and K. pneumonia strain ATCC 43816. Permeabilization of OM by 4 mM EDTA was confirmed by increased susceptibility to vancomycin (MICs of 25 μg/ml for E. aerogenes ATCC 13048 and 12.5 μg/ml for K. pneumonia strain ATCC 43816), which is inactive against OM-intact Gram-negative bacteria. Red circles show the area of the molecule where modifications are tolerated, whereas blue circles show areas where modifications lead to loss of activity against E. coli. MICs were determined by microdilution.

Mutations that conferred resistance to G0507 mapped to three different proteins of the ABC transporter LolCDE complex (Fig. 2). Interestingly, a few of the mutations (e.g., LolEL371P and LolEP372L) were also identified to confer resistance to compound 2 (13). All identified mutations in LolC and LolE are in the predicted periplasmic domain or in the periplasm/inner membrane interface (Fig. 2). Since a high-resolution structure of the LolCDE complex is not available, it is unclear whether the amino acids in LolC and LolE that are affected by mutations constitute a distinct pocket in the quaternary structure to which compounds bind. However, the wide range of positions in LolC and LolE that can be mutated suggests that the mutations likely affect the overall function of LolCDE rather than directly affecting compound binding. This notion is corroborated by our SPR data showing that the LolCQ258K substitution does not affect G0507 binding to LolCDE. There are several potential mechanisms for how the LolCQ258K substitution might abrogate the effect of G0507. For instance, it might be possible that G0507 binding to LolCDE leads to futile ATP hydrolysis that might be detrimental to protein function. The LolCQ258K substitution might prevent or suppress futile ATP hydrolysis cycles, thereby restoring the proper function of LolCDE. This notion is consistent with our observation that G0507 binding to LolCDE leads to an increase in LolCDE ATPase activity, while the LolCQ258K substitution abrogates this effect. A previous study demonstrated that a mutation at the extracellular end of a transmembrane helix in the multidrug ABC transporter Pdr5 uncouples ATPase activity from drug transport and renders the transporter nonfunctional (36). It is possible that G0507 binding to LolCDE results in unique conformational changes in the transmembrane domain of LolCDE that lead to an aberrant cross talk between the transmembrane domain and the ATPase domains, resulting in futile ATPase hydrolysis cycles. Mutations in LolD might be able to restore normal ATPase activity, thereby rendering E. coli cells insensitive to G0507. Interestingly, three out of four mutations identified in LolD are in the vicinity of Walker A and Walker B motifs that are involved in binding and hydrolysis of ATP (Fig. 2). Alternatively, G0507 might interfere with lipoprotein binding to LolCDE. Mutations in LolCDE could allow binding of lipoproteins to LolCDE in the presence of bound G0507, thereby allowing proper lipoprotein trafficking. Nevertheless, our data suggest that G0507 is inhibiting the function of LolCDE by a mechanism other than inhibition of its ATPase activity. Future work in the presence of lipoprotein substrates might shed light on how G0507 is interfering with lipoprotein trafficking mediated by LolCDE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All chemicals and reagents were of molecular biology grade and were purchased and used according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Test compounds for the primary cell viability assay were prepared in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 10 mM and screened at a final assay concentration of 20 μM. DNA polymerases (Phusion HF and Taq), restriction endonucleases, DNA modification enzymes, and DNA ladders were from New England BioLabs. Plasmid purification, PCR purification, and DNA gel extraction kits were obtained from Qiagen and used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. DNA samples were analyzed using an E-Gel iBase power system using the appropriate E-Gel agarose gels.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Information on the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study is outlined in Table 2. E. coli K-12 strains MG1655 and BW25113 and their derivatives were used for all the experiments with the exception that E. coli TOP10 cells were used for cloning. Arabinose-inducible strains were constructed as described below. Cultures were grown with aeration at 30°C or 37°C in LB broth (Sigma), unless otherwise stated, with appropriate antibiotics (carbenicillin, 50 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; hygromycin, 100 μg/ml). LB broth was supplemented with arabinose or glucose where indicated. EDTA (4 mM) was added to the LB broth to permeabilize the OMs of E. aerogenes strain ATCC 13048 and K. pneumonia strain ATCC 43816.

Mutant strain construction.

To construct an arabinose-inducible msbA conditional knockout strain (GNEID3536), the msbA open reading frame (ORF) was cloned into the EcoRI/XbaI sites of expression vector pBAD24 using PCR primers msbA-f2 and msbA-r2. Arabinose-inducible msbA was subcloned from pBAD24 into the SacI site of the integration vector pLDR9 using PCR primers PBAD-msbA-f and PBAD-msbA-r. The NotI-digested and religated construct was integrated into the lambda attB site according to a previously described protocol (37). The endogenous msbA gene was then replaced with a promoterless kanamycin marker flanked by Flp recombinase target (FRT) sites, amplified from pKD4 using primers msbA-KO-noPkan-f and msbA-KO-kan-r, and integrated into MG1655 by Red recombinase-mediated homologous recombination (38).

The conditional lptD strain (GNEID0092) was created by inserting PBAD-lptD at the attB site in MG1655, followed by deletion of the native copy of lptD (38, 39). Briefly, lptD was cloned into pBAD24 using standard methods. PBAD-lptD was amplified from pBAD24-lptD and subcloned into pLDR9. pLDR9-PBAD-lptD was digested with XbaI, ligated, and transformed into MG1655 expressing pLDR8. PCR and DNA sequencing confirmed insertion of PBAD-lptD at the attB site. After integration of PBAD-lptD, the native copy of lptD was deleted using λ Red recombination.

Construction of a σE reporter strain.

Chromosomal deletion of the lacZYA operon was generated using the λ Red recombinase system (38), with the aid of the temperature-sensitive pSIM18 red expression vector (39). The operon was completely replaced with a kanamycin resistance cassette amplified from pKD13 (N3P-29 and N3P-30), under the recommended conditions, followed by removal of the cassette using the pCP20 helper plasmid. The reporter strain was created by integration of a transcriptional fusion of the rpoHP3 promoter to the β-galactosidase gene (lacZ) at the lambda attB integration site. Briefly, the rpoHP3 promoter fusion was created by amplifying the lacZ gene with primer pair N3P-25 and N3P-26, whereby the forward primer encoded the rpoHP3 promoter region with a strong ribosome-binding site. The amplified rpoHP3-lacZ product was cloned into BamHI-PstI sites of pLDR9, creating pGNE7. The resulting vector was digested with NotI, and the fragment of interest was ligated and transformed into the MG1655 Δlac strain with pLDR8, expressing the lambda integrase (int) for site-specific integration at the attB site. PCR was used to confirm the upstream and downstream integration sites, and expression of the lacZ gene was tested by a β-galactosidase activity assay. For screening, the new strain, MG1655 Δlac attB::rpoHP3-lacZ (GNEID1187), was made more permeable to small compounds by transducing the tolC efflux mutation (tolC::aph, kanamycin resistance cassette) from the Keio collection, creating MG1655 Δlac attB::rpoHP3-lacZtolC::aph (GNEID1222).

Plasmid construction.

The σE reporter fusion was created by linking the well-characterized σE-specific promoter rpoHP3 to the β-galactosidase gene (lacZ) with a strong ribosome-binding site. The rpoHP3-lacZ gene fusion was amplified using forward primer N3P-076 and reverse primer N3P-077 using pGNE7 (see above for details) as the template DNA and cloned into BamHI-HindIII digested pACYC184 low-copy-number vector (pGNE18).

To allow us to control the expression of the major lipoprotein, Lpp or Braun's lipoprotein, full-length Lpp or Lpp with the C-terminal lysine removed (ΔK58) and a C-terminal 6×His tag was cloned into pBAD24 under the control of the PBAD arabinose inducible promoter. Full-length Lpp was amplified with primers N3P-162 and N3P-163, and LppΔK58-6×His was amplified with primers N3P-162 and N3P-164 and cloned into pBAD24 (pGEN68 and pGNE69, respectively). The correct sequence of all constructs was verified by DNA sequencing. To allow monitoring of inducible Lpp, Lpp constructs were transformed into a mutant strain that had lost Lpp, as confirmed by Western blotting using Lpp-specific polyclonal antibodies and whole-genome sequencing. Overnight cultures were diluted into fresh LB medium and grown to an A600 of ∼0.4 to 0.5. Lpp was induced with 0.1% arabinose in the presence or absence of compound at 4× MIC and incubated for 1 h. Sample preparation for membrane fractionation or Lpp purification is described below.

Growth inhibition screen.

A subset (∼35,000 compounds) of the Roche/Genentech small-molecule library was screened at 20 μM for growth inhibition of E. coli imp4213, ΔtolC, and wild-type MG1655 strains. The same compounds were also screened for inhibition of wild-type S. aureus USA300. A total of 10 μl of 2 × 105 CFU/ml bacteria in LB medium was dispensed into Greiner-Bio Cellstar 384-well plates containing compounds in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The final concentration of DMSO was 0.4%. Plates were incubated statically at 37°C with humidity for 4 h before addition of an equal volume of BacTiterGlo (BTG) reagent (Promega). After BTG addition, plates were incubated at room temperature for 5 min before luminescence was read with an EnVision Multilabel plate reader. Tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and polymyxin B were used as controls that completely inhibited growth of all tested Gram-negative bacterial strains. A total of 111 hits were selected that showed a luminescence decrease of greater than three standard deviations from a DMSO control mean in the imp4213 and ΔtolC strains. Among the 111 hits, 42 did not show activity against the wild-type S. aureus USA300 strain. Forty-four compounds showed activity against the wild-type E. coli MG1655 strain.

Measurement of σE levels in mutant E. coli strains.

Wild-type K-12 and mutant strains harboring the rpoHP3-lacZ reporter vector pGNE18 were tested for their basal σE levels. Strains harboring the reporter vector were grown overnight at 30°C. As the σE promoter is induced in late exponential phase and stationary phase, β-galactosidase enzyme accumulates within cells during overnight growth. To reduce background β-galactosidase enzyme, cells were back-diluted the next morning to an A600 of ∼ 0.0025. Cultures were grown at 30°C until the A600 was between 0.2 and 0.4; this allowed sufficient time for the accumulated β-galactosidase enzyme to be diluted out. Twenty-microliter aliquots of cells were removed from the cultures and transferred into 96-well white Maxisorp FluoroNunc microplates, and β-galactosidase expression/activity was measured by adding 20 μl of Beta-Glo assay reagent (Promega). Luminescence was detected using a SpectraMax M5 instrument (Molecular Devices). β-Galactosidase activity was normalized for cell numbers by dividing the activity by the A600. σE fold induction in mutant strains was calculated as the β-galactosidase activity of the mutant divided by the β-galactosidase activity of wild-type cells growing under the same condition.

Measurement of σE induction in the presence of small-molecule compounds.

Reporter strains, MG1655 Δlac attB::rpoHP3-lacZ and MG1655 Δlac attB::rpoHP3-lacZ tolC::aph, were grown overnight at 30°C. To reduce background β-galactosidase enzyme levels, cultures were grown for 8 h at 30°C and diluted back multiple times, making sure the cell density never reached an A600 of 0.4. Cells were centrifuged and washed with LB broth and frozen in LB plus 10% glycerol at an A600 of 10 (approximately 4 × 109 CFU/ml).

Compounds were prepared in 100% DMSO at 10 mM. Assay plates with dose points at 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 7.5, 3.7, 1.85, 0.925, and 0.46 μM, in duplicate, were generated by acoustic liquid dispensing using a Labcyte Echo 555 instrument and 384-well assay plates (black with clear, flat bottoms; Corning). Frozen aliquots of the reporter strains (MG1655 Δlac attB::rpoHP3-lacZ or MG1655 Δlac attB::rpoHP3-lacZ tolC::aph) were thawed and diluted 1:4,000 into fresh LB broth, and 10 μl per well was dispensed into the assay plates (approximately 1 × 104 CFU per well); duplicate assay plates were used, one to measure cell viability and one to measure β-galactosidase activity. After 5 h of growth, cell viability was measured using a BacTiter-Glo microbial cell viability assay (Promega), and β-galactosidase expression/activity was measured using a Beta-Glo assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. BacTiter-Glo was used as a measure of cell viability because it allows the measurement of cell numbers that are below the level of detection achievable by measuring optical density (OD). Both assay systems are designed to generate a luminescent signal. Luminescence was detected using an EnVision instrument (PerkinElmer). β-Galactosidase activity was normalized for cell numbers by dividing the activity by the BacTiter-Glo activity. σE induction by small-molecule compounds was calculated as the normalized β-galactosidase activity in the presence of compound divided by the normalized β-galactosidase activity in the presence of DMSO. σE induction assays for antimicrobial compounds, as well as follow-up studies with hit compounds, were conducted in 96-well plates and performed under the same conditions with the exception that the incubation time was 4 h.

MICs and frequency of resistance.

MICs were determined according to a standard protocol from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (40). Briefly, bacteria were harvested from a fresh overnight agar plate and inoculated (approximately 106 CFU · ml−1) into serially diluted antibiotics or compounds in 96-well, round-bottom assay plates (Corning). Assay plates were incubated for 20 h at 37°C, and MICs were determined by visual inspection of the lowest concentration showing the absence of growth.

To determine the frequency of spontaneous resistance, suspensions containing approximately 5 × 108 CFU of bacteria were cultured on LB agar 35-mm plates containing 4-, 8-, or 16-fold the determined agar MIC. Input was calculated in parallel by plating serial dilutions of bacterial suspensions on plates without compound. The frequency of spontaneous resistance was defined as the number of viable colonies able to grow in the presence of compound after growth at 37°C for 2 days divided by the input.

Whole-genome sequencing.

Whole-genome sequencing was carried out on DNA from 10 G0507-resistant mutants using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument with 2- by 75-bp paired reads. All fastq files were filtered for read quality, and reads where at least 70% of the cycles had Phred scores of ≥23 were kept. Filtered reads were aligned to the E. coli K-12 MG1655 reference genome (GenBank accession no. NC_000913) using GSNAP (10 October 2013 version) (41), and variant analysis was performed using the Bioconductor package VariantTools (42). To increase confidence in variant calls, base quality scores of 30 or higher were required. Only mutations present in more than 50% of total reads were considered to be dominant.

For follow-up analysis of additional resistance mutants, the lolCDE operon was sequenced. The primer pair N3P-149/N3P-150 was used to amplify the complete lolCDE operon, and primers N3P-151 through N3P-157 were used for in-house DNA sequencing.

Microscopy.

E. coli MG1655 imp4213 bacteria grown to log phase were treated with 4× MIC of each compound for 2 h before being washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in methanol overnight to fix the cells. The next day cells were washed in PBS and resuspended in PBS supplemented with 10 μg · ml−1 Nile Red (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 5 min. Cells were diluted onto a coverslip and allowed to dry. The coverslip was mounted onto a slide using ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (ThermoFisher Scientific) and cured overnight. Images were acquired using confocal fluorescence microscopy using a 100× oil objective.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Total cell extracts, cellular fractions, and purified protein samples were diluted in SDS sample buffer and heated at 95°C for 5 min, where appropriate. Protein samples were separated by electrophoresis in an XCell Sure Lock system using either 4 to 12% bis-Tris NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) in Novex morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) SDS running buffer or 16% Tricine gels (Invitrogen) in Novex Tricine SDS running buffer. Gels were either stained with Coomassie brilliant blue or electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membrane using an iBlot Dry Blotting system (ThermoFisher Scientific). Immunoblotting was performed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Lpp or MsbA or mouse monoclonal antibodies against BamA. Rabbit-specific and mouse-specific peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were detected by chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Purification of Lpp-His.

The LppΔK58-His6 expression vector was transformed into a mutant strain that had lost the ability to produce wild-type Lpp. These cells were grown to an A280 of 0.5, and 4× MIC of compound was added to block the lipoprotein biosynthetic pathway, followed by 0.1% arabinose to induce the expression of LppΔK58-6×His for 1 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5 with EDTA-free Complete protease inhibitor [Roche)], and broken using an LV1 Microfluidizer homogenizer (Microfluidics). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 4,000 × g, and total membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation at 260,000 × g for 1 h. Membranes were solubilized in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 1% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (DDM) for 1 h at room temperature. His-tagged protein was purified on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose (Qiagen) using wash buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.05% DDM) and eluted with 250 mM imidazole. Intact mass analysis of protein samples was performed by LC-MS by JadeBio (La Jolla).

Separation of inner and outer membranes by sucrose floatation gradient.

Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, plus Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Cells were disrupted by two passages through an LV1 Microfluidizer homogenizer (Microfluidics). The cell lysate was supplemented with 10 μg/ml of DNase I, and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 4,000 × g. Membranes were collected by ultracentrifugation at 260,000 × g for 1 h and washed once with HEPES buffer. Membranes were resuspended in 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and sucrose was dissolved to achieve >60% (wt/wt) saturation. The inner and outer membranes were separated by floatation in a sucrose gradient for 40 h at 230,000 × g at 10°C as described elsewhere (43). Fractions were removed and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with appropriate antibodies.

Cloning, expression, and purification of E. coli LolCDE complex.

The E. coli LolC and LolD cDNAs were synthesized and cloned into the pCDF-Duet-1 vector (Novagen) containing a C-terminal tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site and an octahistidine tag (p770999). The E. coli LolE gene was synthesized and cloned into the pRSF-Duet-1 vector (Novagen) with a C-terminal TEV protease cleavage site followed by a Strep tag (p771003). Plasmids were cotransformed into BL21(DE3) with the appropriate antibiotic selection. Cultures were grown in Terrific Broth autoinduction medium (Millipore Sigma), and protein production was induced by incubation at 16°C for 64 h. All remaining steps were performed at 4°C unless otherwise indicated. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer and lysed using a Microfluidizer (Microfluidics). A crude membrane-containing pellet fraction was isolated by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 30 min. Membranes were solubilized in solubilization buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 5 mM ATP, 1% DDM containing protease inhibitors [Complete EDTA-free; Roche]) for 2 h with gentle stirring. The solubilized protein was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 45 min, and the supernatant was retained. The LolCDE complex was then isolated by immobilized nickel affinity chromatography (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by resolution on a Superose 6 gel filtration column in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, and 0.01% DDM. Fractions containing the LolCDE complex were pooled and concentrated to 2 mg/ml using a 100,000-molecular-weight-cutoff (MWCO) concentrator (Millipore Sigma), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. To reconstitute the LolCDE complex in amphipol A8-35, amphipol was added at a ratio of 1:2 (milligrams of protein per milligrams of amphipol) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The sample was then resolved on a Superose 6 gel filtration column in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5)–100 mM NaCl. Fractions containing LolCDE complex were pooled, concentrated to 2 mg/ml as described previously, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Protein identity was confirmed by mass spectrometry.

LolCDE ATPase assay.

The ATPase activities of LolCDEWT and LolCQ258KDE were measured using a Transcreener ADP2 FP assay (BellBrook Labs, Madison, WI, USA) at room temperature. Compounds were incubated with 2× LolCDE enzyme solution for 10 min, followed by addition of 2× ATP solution to initiate the ATPase reaction. The final condition of the ATPase reaction mixture is 10 nM LolCDE in DDM, 50 μM ATP in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% glycerol, 0.1% BGG, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.007% Brij 35, and 1% DMSO. The reaction was quenched after 1 h by the addition of Transcreener detection buffer when about 5% ATP was hydrolyzed to ADP. The IC50s were determined by fitting the inhibition dose-response curve with a nonlinear four-parameter inhibition model (GraphPad Prism).

Km and kcat values were determined using a real-time Transcreener format that allowed continuous monitoring of the ATPase reaction. Enzyme (10 nM) was incubated with various ATP concentrations, and linear initial velocity was measured from the time course of the ATPase reaction using ADP standard curves to calculate the amount of ADP produced. A plot of the initial velocity versus ATP concentration was fitted to a hyperbolic function to determine Km and kcat values.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis.

Binding studies were preformed on a Biacore T200 system maintained at 20°C. The streptavidin (SA) sensor chip was docked, and the system was primed with running buffer (RB) composed of 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350, and 4.5% DMSO. LolCDE protein at 0.30 mg/ml in RB was injected at a rate of 5 μl/min for 100 s, capturing 3,000 RU of mutant LolCDE onto channel 2 and 4,000 RU of WT LolCDE onto channel 4. Compounds were injected at a flow rate of 100 μl/min for 5 s with dissociation for 20 s (five serial 3-fold dilutions of compound in RB). Each dose-response series was performed in duplicate and double referenced against responses obtained from both a noncoated surface and a blank sample injection. An affinity isotherm was fitted to the resulting binding response curves using BIAevaluation. KD (equilibrium dissociation constant) values are necessarily approximate owing to the narrow effective concentration range used.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jeremy Stinson for the Illumina sequencing and members of Genentech Infectious Diseases Department for valuable feedback on this research.

Jessica V. Hankins is currently employed at the FDA, Silver Spring, Maryland, USA.

The views expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the views of the FDA or the United States.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02151-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nikaido H. 2003. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikaido H, Vaara M. 1985. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev 49:1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silhavy TJ, Kahne D, Walker S. 2010. The bacterial cell envelope. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000414. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Z, White K, Polissi A, Georgopoulos C, Raetz CR. 1998. Function of Escherichia coli MsbA, an essential ABC family transporter, in lipid A and phospholipid biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 273:12466–12475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruiz N, Gronenberg LS, Kahne D, Silhavy TJ. 2008. Identification of two inner-membrane proteins required for the transport of lipopolysaccharide to the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:5537–5542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801196105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bos MP, Tefsen B, Geurtsen J, Tommassen J. 2004. Identification of an outer membrane protein required for the transport of lipopolysaccharide to the bacterial cell surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:9417–9422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402340101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClerren AL, Endsley S, Bowman JL, Andersen NH, Guan Z, Rudolph J, Raetz CR. 2005. A slow, tight-binding inhibitor of the zinc-dependent deacetylase LpxC of lipid A biosynthesis with antibiotic activity comparable to ciprofloxacin. Biochemistry 44:16574–16583. doi: 10.1021/bi0518186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivas N, Jetter P, Ueberbacher BJ, Werneburg M, Zerbe K, Steinmann J, van der Meijden B, Bernardini F, Lederer A, Dias RL, Mission PE, Henze H, Zumbrunn J, Gombert FO, Obrecht D, Hunziker P, Schauer S, Ziegler U, Käch A, Eberl L, Riedel K, DeMarco SJ, Robinson JA. 2010. Peptidomimetic antibiotics target outer-membrane biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Science 327:1010–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.1182749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu T, Malinverni J, Ruiz N, Kim S, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. 2005. Identification of a multicomponent complex required for outer membrane biogenesis in Escherichia coli. Cell 121:235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aoki SK, Malinverni JC, Jacoby K, Thomas B, Pamma R, Trinh BN, Remers S, Webb J, Braaten BA, Silhavy TJ, Low DA. 2008. Contact-dependent growth inhibition requires the essential outer membrane protein BamA (YaeT) as the receptor and the inner membrane transport protein AcrB. Mol Microbiol 70:323–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagan CL, Wzorek JS, Kahne D. 2015. Inhibition of the β-barrel assembly machine by a peptide that binds BamD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:2011–2016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415955112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okuda S, Tokuda H. 2011. Lipoprotein sorting in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:239–259. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeod SM, Fleming PR, MacCormack K, McLaughlin RE, Whiteaker JD, Narito S, Mori M, Tokuda H, Miller AA. 2015. Small-molecule inhibitors of Gram-negative lipoprotein trafficking discovered by phenotypic screening. J Bacteriol 197:1075–1082. doi: 10.1128/JB.02352-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nayar AS, Dougherty TJ, Ferguson KE, Granger BA, McWilliams L, Stacey C, Leach LJ, Narita S, Tokuda H, Miller AA, Brown DG, McLeod SM. 2015. Novel antibacterial targets and compounds revealed by a high-throughput cell wall reporter assay. J Bacteriol 197:1726–1734. doi: 10.1128/JB.02552-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yakushi T, Masuda K, Narita S, Matsuyama S, Tokuda H. 2000. A new ABC transporter mediating the detachment of lipid-modified proteins from membrane. Nat Cell Biol 2:212–218. doi: 10.1038/35008635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowicz M, Silhavy TJ. 2017. Redefining the essential trafficking pathway for outer membrane lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:4769–4774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702248114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mecsas J, Rouviere PE, Erickson JW, Donohue TJ, Gross CA. 1993. The activity of sigma E, an Escherichia coli heat-inducible sigma-factor, is modulated by expression of outer membrane proteins. Genes Dev 7:2616–2628. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tam C, Missiakas D. 2005. Changes in lipopolysaccharide structure induce the σE-dependent response of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 55:1403–1412. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima S, Guo MS, Chaba R, Gross CA, Sauer RT. 2013. Dual molecular signals mediate the bacterial response to outer-membrane stress. Science 340:837–841. doi: 10.1126/science.1235358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain M, Ozawa Y, Ichihara S, Mizushima S. 1982. Signal peptide digestion in Escherichia coli, effect of protease inhibitors on hydrolysis of the cleaved signal peptide of the major outer-membrane lipoprotein. Eur J Biochem 129:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb07044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V, Bosch V. 1972. Sequence of the murein-lipoprotein and the attachment site of the lipid. Eur J Biochem 28:51–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1972.tb01883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yakushi T, Tajima T, Matsuyama S, Tokuda H. 1997. Lethality of the covalent linkage between mislocalized major outer membrane lipoprotein and the peptidoglycan of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 179:2857–2862. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2857-2862.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee N, Yamagata H, Inouye M. 1983. Inhibition of secretion of a mutant lipoprotein across the cytoplasmic membrane by the wild-type lipoprotein of the Escherichia coli outer membrane. J Bacteriol 155:407–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu HC, Hou C, Lin JJ, Yem DW. 1977. Biochemical characterization of a mutant lipoprotein of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 74:1388–1392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.4.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin JJ, Kanazawa H, Ozols J, Wu HC. 1978. An Escherichia coli mutant with an amino acid alteration within the signal sequence of outer membrane prolipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 75:4891–4895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doi Y, Park YS, Rivera JI, Adams-Haduch JM, Hingwe A, Sordillo EM, Lewis JS II, Howard WJ, Johnson LE, Polsky B, Jorgensen JH, Richter SS, Shutt KA, Peterson KL. 2013. Community-associated extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 56:641–648. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, Doi Y, Tiang G, Dong B, Huang X, Yu LF, Gu D, Ren H, Chen X, Lv L, He D, Zhou H, Liang Z, Liu JH, Shen J. 2016. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong Q, Yang J, Liu Q, Alamuri P, Roland KL, Curtiss R 3rd. 2011. Effect of deletion of genes involved in lipopolysaccharide core and O-antigen synthesis on virulence and immunogenicity of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect Immun 79:4227–4239. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05398-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raetz CR, Revnolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. 2007. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem 76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Typas A, Banzhaf M, van den Berg van Saparoea B, Verheul J, Biboy J, Nichols RJ, Zietek M, Beilharz K, Kannenberg K, von Rechenberg M, Breukink E, den Blaauwen T, Gross CA, Vollmer W. 2010. Regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis by outer membrane proteins. Cell 143:1097–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paradis-Bleau C, Markovski M, Uehara T, Lupoli TJ, Walker S, Kahne DE, Bernhardt TG. 2010. Lipoprotein cofactors located in the outer membrane activate bacterial cell wall polymerases. Cell 143:1110–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaara M. 1992. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol Rev 56:395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bury-Moné S, Nomane Y, Reymond N, Barbet R, Jacquet E, Imbeaud S, Jacq A, Bouloc P. 2009. Global analysis of extracytoplasmic stress signaling in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet 5:e1000651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babu M, Díaz-Mejía JJ, Vlasblom J, Gagarinova A, Phanse S, Graham C, Yousif F, Ding H, Xiong X, Nazarians-Armavil A, Alamgir M, Ali M, Pogoutse P, Pe'er A, Arnold R, Michaut M, Parkinson J, Golshani A, Whitfield C, Wodak SJ, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Greenblatt JF, Emili A. 2011. Genetic interaction maps in Escherichia coli reveal functional crosstalk among cell envelope biogenesis pathways. PLoS Genet 7:e1002377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenz C, Dougherty TJ, Lory S. 2016. Transcriptional responses of Escherichia coli to a small-molecule inhibitor of LolCDE, an essential component of the lipoprotein transport pathway. J Bacteriol 198:3162–3175. doi: 10.1128/JB.00502-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sauna ZE, Bohn SS, Rutledge R, Dougherty MP, Cronin S, May L, Xia D, Ambudkar SV, Golin J. 2008. Mutations define cross-talk between the N-terminal nucleotide-binding domain and transmembrane helix-2 of the yeast multidrug transporter Pdr5: possible conservation of a signaling interface for coupling ATP hydrolysis to drug transport. J Biol Chem 283:35010–35022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806446200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diederich L, Rasmussen LJ, Messer W. 1992. New cloning vectors for integration in the lambda attachment site attB of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Plasmid 28:14–24. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(92)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan W, Costantino N, Li R, Lee SC, Su Q, Melvin D, Court DL, Liu P. 2007. A recombineering based approach for high-throughput conditional knockout targeting vector construction. Nucleic Acids Res 35:e64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2007. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 17th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S17. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu TD, Nacu S. 2010. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics 26:873–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrence M, Degenhardt J, Gentleman R. 2016. VariantTools: tools for working with genetic variants. R package version 1.14.1. https://bioconductor.statistik.tu-dortmund.de/packages/3.3/bioc/html/VariantTools.html.

- 43.Robichon C, Vidal-Ingigliardi D, Pugsley AP. 2005. Depletion of apolipoprotein N-acyltransferase causes mislocalization of outer membrane lipoproteins in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 280:974–983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yasuda M, Iguichi-Yokoyama A, Matsuyama S, Tokuda H, Narita S. 2009. Membrane topology and functional importance of the periplasmic region of ABC transporter LolCDE. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 73:2310–2316. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J Bacteriol 177:4121–4130. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.