ABSTRACT

Cryptic species of Aspergillus fumigatus, including the Aspergillus viridinutans species complex, are increasingly reported to be causes of invasive aspergillosis. Their identification is clinically relevant, as these species frequently have intrinsic resistance to common antifungals. We evaluated the susceptibilities of 90 environmental and clinical isolates from the A. viridinutans species complex, identified by DNA sequencing of the calmodulin gene, to seven antifungals (voriconazole, posaconazole, itraconazole, amphotericin B, anidulafungin, micafungin, and caspofungin) using the reference European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) method. The majority of species demonstrated elevated MICs of voriconazole (geometric mean [GM] MIC, 4.46 mg/liter) and itraconazole (GM MIC, 9.85 mg/liter) and had variable susceptibility to amphotericin B (GM MIC, 2.5 mg/liter). Overall, the MICs of posaconazole and the minimum effective concentrations of echinocandins were low. The results obtained by the EUCAST method were compared with the results obtained with Sensititre YeastOne (YO) panels. Overall, there was 67% agreement (95% confidence interval [CI], 62 to 72%) between the results obtained by the EUCAST method and those obtained with YO panels when the results were read at 48 h and 82% agreement (95% CI, 78 to 86%) when the results were read at 72 h. There was a significant difference in agreement between antifungals; agreement was high for amphotericin B, voriconazole, and posaconazole (70 to 86% at 48 h and 88 to 93% at 72 h) but was very low for itraconazole (37% at 48 h and 57% at 72 h). The agreement was also variable between species, with the maximum agreement being observed for A. felis isolates (85 and 93% at 48 and 72 h, respectively). Elevated MICs of voriconazole and itraconazole were cross-correlated, but there was no correlation between the other azoles tested.

KEYWORDS: cryptic species, Aspergillus felis, Aspergillus udagawae, amphotericin B, voriconazole, posaconazole, itraconazole, echinocandins

INTRODUCTION

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is one of the major mold infections, with IA resulting in high fatality rates among severely immunocompromised patients (1). Aspergillus fumigatus is the main etiologic agent of IA (2). Other Aspergillus species belonging to Aspergillus section Fumigati may occasionally cause IA, and most of them have been described in the last 2 decades with the advent of molecular genetic methods (3). These species are frequently referred to as cryptic because they are morphologically similar to each other or to A. fumigatus and are often misidentified using conventional identification techniques (4–6). Misdiagnosis may have important consequences, as these A. fumigatus-related species often display some level of resistance to azoles and other antifungal drugs. Aspergillus lentulus, A. udagawae, A. viridinutans, and A. thermomutatus (Neosartorya pseudofischeri) have been most commonly associated with refractory cases of IA (3). Therefore, accurate species identification and antifungal susceptibility testing are required to guide therapy since the MICs of most antifungal drugs are higher for cryptic species than for A. fumigatus sensu stricto and azole cross-resistance can occur (3, 7, 8).

The A. viridinutans species complex contains morphologically similar, soil-inhabiting species that have been increasingly reported in recent years to be opportunistic human and animal pathogens with a clinical spectrum, including IA, chronic IA, and keratitis in humans, sino-orbital aspergillosis in cats, and disseminated IA in dogs (3, 5, 6, 9). This complex currently encompasses 10 species, and at least 6 of them are clinically relevant (5, 6, 9–13). Compared to the MICs for A. fumigatus, the MICs of a wider variety of antifungal agents for A. viridinutans species complex species are elevated (14). Despite the relatively high number of recently reported clinical cases, the antifungal susceptibly profiles of a large data set of reliably identified species have not been tested.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the in vitro antifungal susceptibility patterns of the A. viridinutans species complex to seven antifungals (voriconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, amphotericin B, anidulafungin, micafungin, and caspofungin). Ninety isolates originating from human and animal specimens and from various environmental sources were tested. The results obtained by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) reference method were compared with those obtained with the widely used commercial Sensititre YeastOne (YO) panels to verify its applicability for antifungal susceptibility testing of cryptic species of A. fumigatus.

RESULTS

Molecular identification of isolates.

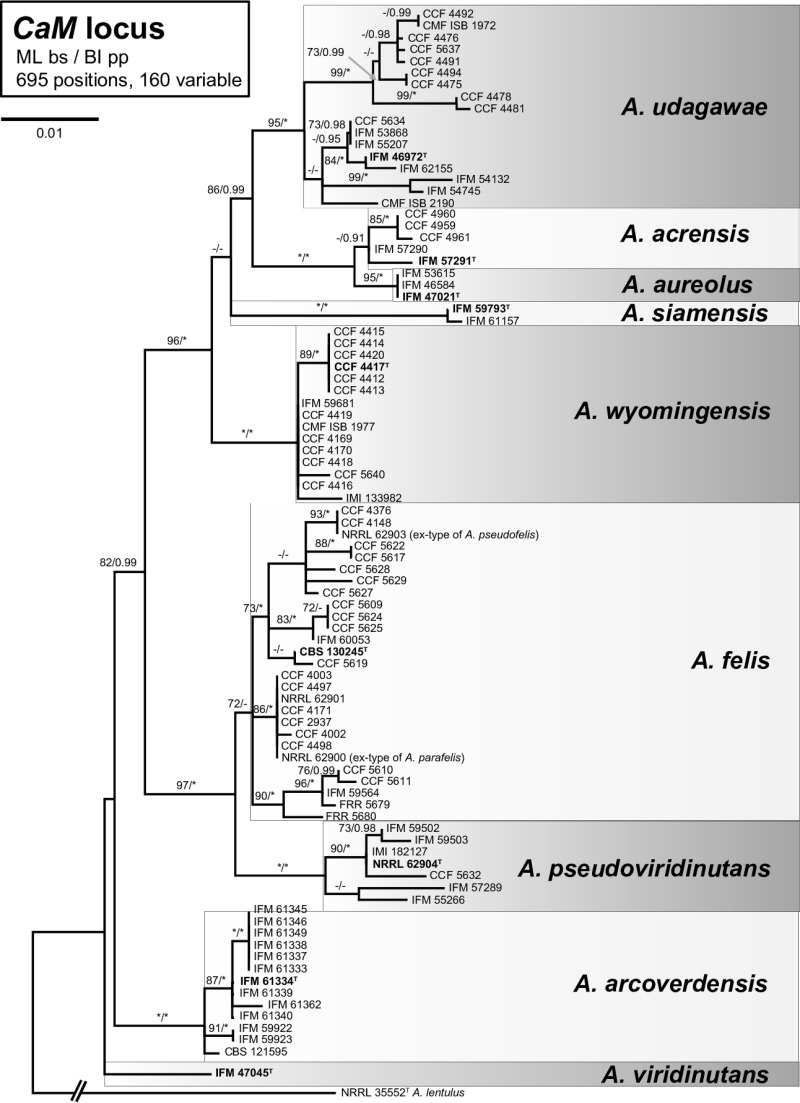

The phylogenetic analyses performed using the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods grouped the 90 isolates into several monophyletic and well-supported clades or single-isolate lineages (Fig. 1) corresponding to A. udagawae (n = 17), A. wyomingensis (n = 15), A. arcoverdensis (n = 13), A. pseudoviridinutans (n = 7), A. aureolus (n = 3), A. siamensis (n = 2), and A. viridinutans (n = 1). Five environmental isolates (IFM 57290, IFM 57291, CCF 4659, CCF 4660, CCF 4661) which did not produce ascomata and had green colonies were clustered as a sister branch to homothallic A. aureolus isolates with yellow colonies. Despite the close phylogenetic relationships, it is unlikely that these strains represent A. aureolus due to significant morphological differences and a heterothallic reproductive strategy. A new species status (A. acrensis sp. nov.) is currently proposed for these strains (49). The ex-type strains of A. felis, A. pseudofelis, and A. parafelis clustered in one robust clade, and the phylogenetic analysis did not allow a clear distinction between these three species. Multiple gene phylogeny and in vitro mating experiment data indicate that these taxa are conspecific (49). Therefore, we considered all isolates belonging to this clade to be A. felis.

FIG 1.

A 50% majority rule consensus maximum likelihood tree based on partial calmodulin gene (CaM) sequences shows the relationships of the 90 tested isolates belonging to the Aspergillus viridinutans complex. The maximum likelihood bootstrap proportion and Bayesian posterior probability are appended to the nodes; only bootstrap proportions of ≥70% and posterior probabilities of ≥90% are shown; lower levels of support are indicated with a hyphen, whereas asterisks indicate full support (a bootstrap proportion of 100% or a posterior probability of 1.00); ex-type strains are designated in boldface with a superscript T. The tree is rooted with A. lentulus NRRL 35552.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The MIC ranges, MIC50s, MIC90s, and geometric mean (GM) MIC values obtained by the EUCAST reference method are shown in Table 1. The majority of the tested strains showed elevated MICs of itraconazole and voriconazole and frequently also elevated MICs of amphotericin B. The GM MIC of voriconazole ranged from 2.52 mg/liter for A. aureolus to 5.81 mg/liter for A. arcoverdensis. One-half of the strains of all species except A. arcoverdensis were inhibited by a voriconazole concentration of ≤4 mg/liter. High MICs were observed for itraconazole, with the GM MIC being 9.85 mg/liter and the MIC50 being >8 mg/liter for all 90 isolates. In contrast, low MICs were determined for posaconazole, the GM MIC of which ranged from 0.16 mg/liter for A. wyomingensis to 0.45 mg/liter for A. arcoverdensis. Susceptibility to amphotericin B was variable across the tested species; half of the isolates of each species were inhibited by a concentration of ≤2 mg/liter, and the highest MICs were obtained for A. udagawae. The minimum effective concentrations (MECs) determined for the echinocandins (anidulafungin, micafungin, and caspofungin) were low for almost all isolates, and the GM MIC was 0.04 mg/liter for anidulafungin, 0.05 mg/liter for caspofungin, and 0.05 mg/liter for micafungin.

TABLE 1.

Antifungal susceptibilities of 90 strains from the Aspergillus viridinutans complex by EUCAST reference method and percent agreement with Sensititre YeastOne panela

| Species (no. of isolates) | Test agent | MIC by EUCAST (mg/liter) |

% agreement with YeastOne panel |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | GM | 50% | 90% | Range at 48 h | 48 h | Range at 72 h | 72 h | ||

| A. felis (27) | VRC | 1 to >8 | 4.79 | 4 | >8 | 0.5 to 4 | 100 | 1 to >8 | 100 |

| ITC | 1 to >8 | 13.3 | >8 | >8 | 0.03 to >16 | 44.4 | 0.25 to >16 | 70.4 | |

| POS | 0.125 to 2 | 0.39 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.03 to 1 | 96.3 | 0.06 to 0.5 | 100 | |

| AMB | 0.25 to 8 | 1.63 | 2 | 8 | 0.25 to 4 | 100 | 1 to 8 | 100 | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.125 | 0.03 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 8 | 0.08 | ≤0.0312 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.0625 | 0.03 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 85.2 | 92.6 | |||||||

| A. udagawae (17) | VRC | 1 to >8 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0.12 to 4 | 76.5 | 0.25 to 8 | 94.1 |

| ITC | 0.25 to >8 | 7.37 | >8 | >8 | 0.03 to >16 | 35.3 | 0.03 to >16 | 52.9 | |

| POS | 0.0625 to 4 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.015 to 0.12 | 58.8 | 0.015 to 0.25 | 82.4 | |

| AMB | 1 to >8 | 3.54 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 to 4 | 76.5 | 0.5 to 8 | 88.2 | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.25 | 0.04 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 2 | 0.07 | ≤0.0312 | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 2 | 0.05 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 61.8 | 79.4 | |||||||

| A. wyomingensis (15) | VRC | 4 to 8 | 4.2 | 4 | 4 | 0.12 to 2 | 33.3 | 0.5 to 2 | 86.7 |

| ITC | 1 to >8 | 9.2 | >8 | >8 | <0.015 to 0.25 | 0 | 0.03 to >16 | 0 | |

| POS | 0.125 to 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.008 to 0.5 | 46.7 | 0.015 to 1 | 80 | |

| AMB | 1 to >16 | 1.3 | 2 | 8 | 0.12 to 4 | 60 | 0.25 to 8 | 73.3 | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.0625 | 0.03 | ≤0.0312 | ≤0.0312 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 0.25 | 0.04 | ≤0.0312 | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.0625 | 0.03 | ≤0.0312 | ≤0.0312 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 35 | 60 | |||||||

| A. arcoverdensis (13) | VRC | 4 to 8 | 5.81 | 8 | 8 | 0.25 to 2 | 53.8 | 1 to 4 | 84.6 |

| ITC | 4 to >8 | 12.3 | >8 | >8 | 0.015 to >16 | 61.5 | 0.5 to >16 | 84.6 | |

| POS | 0.125 to 2 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.008 to 0.25 | 53.8 | 0.06 to 0.5 | 84.6 | |

| AMB | 0.5 to 8 | 1.6 | 2 | 2 | 0.25 to 2 | 84.6 | 1 to 2 | 100 | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.125 | 0.03 | ≤0.0312 | ≤0.0312 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 0.25 | 0.05 | ≤0.0312 | 0.125 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.0625 | 0.03 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 63.5 | 88.5 | |||||||

| A. pseudoviridinutans (7) | VRC | 4 to >8 | 5.3 | 4 | >8 | 1 to 4 | 100 | 1 to 8 | 100 |

| ITC | >8 | ND | >8 | >8 | >16 | 100 | >16 | 100 | |

| POS | 0.125 to 1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.12 to 0.25 | 100 | 0.25 to 1 | 100 | |

| AMB | 0.5 to 8 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 to 2 | 100 | 1 to 4 | 85.7 | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.125 | 0.04 | ≤0.0312 | 0.125 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 0.25 | 0.05 | ≤0.0312 | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.125 | 0.04 | ≤0.0312 | 0.125 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 100 | 96.4 | |||||||

| A. acrensis (5) | VRC | 1 to 4 | 3.3 | 4 | 4 | 1 to 4 | 100 | 4 to 8 | 100 |

| ITC | 1 to 4 | 3.3 | 4 | 4 | 0.06 to 0.12 | 0 | 0.12 to >16 | 40 | |

| POS | 0.125 to 1 | 0.38 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.03 to 0.06 | 40 | 0.06 to 0.12 | 80 | |

| AMB | 1 to 8 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 2 to 4 | 100 | 2 to 4 | 100 | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.0625 | 0.04 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.0625 | 0.04 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 60 | 80 | |||||||

| A. aureolus (3) | VRC | 1 to 4 | 2.52 | ND | ND | 0.25 to 1 | ND | 1 to 4 | ND |

| ITC | 8 to >8 | 12.7 | ND | ND | 0.12 to 0.25 | ND | >16 | ND | |

| POS | 0.125 to 0.5 | 0.25 | ND | ND | 0.06 to 0.12 | ND | 0.12 to 0.25 | ND | |

| AMB | 0.5 to 1 | 0.79 | ND | ND | 0.25 to 1 | ND | 1 to 2 | ND | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 1 | 0.1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 0.125 | 0.05 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 1 | 0.1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 66.7 | 100 | |||||||

| A. siamensis (2) | VRC | 4 | 4 | ND | ND | 0.5 to 1 | ND | 1 to 2 | ND |

| ITC | 4 | 4 | ND | ND | 0.03 to 0.12 | ND | 0.06 to 0.25 | ND | |

| POS | 0.125 to 0.25 | 0.18 | ND | ND | 0.03 to 0.06 | ND | 0.03 to 0.12 | ND | |

| AMB | 0.25 to 1 | 0.5 | ND | ND | 1 to 2 | ND | 1 to 4 | ND | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 0.25 | 0.09 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | 0.25 to 0.125 | 0.18 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ND | 0.03 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 37.5 | 50 | |||||||

| A. viridinutans (1) | VRC | 4 | ND | ND | ND | 0.25 | ND | 0.5 | ND |

| ITC | 4 | ND | ND | ND | <0.015 | ND | 0.03 | ND | |

| POS | 0.125 | ND | ND | ND | <0.008 | ND | 0.015 | ND | |

| AMB | 1 | ND | ND | ND | 0.5 | ND | 0.5 | ND | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Total agreement | 25 | 25 | |||||||

| All isolates (90) | VRC | 1 to >8 | 4.46 | 4 | 8 | 0.12 to 4 | 74.4 | 0.25 to >8 | 93.3 |

| ITC | 0.25 to >8 | 9.85 | >8 | >8 | 0.015 to >16 | 36.7 | 0.03 to >16 | 56.7 | |

| POS | 0.0625 to 4 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.008 to 1 | 70 | 0.015 to 1 | 87.8 | |

| AMB | 0.25 to >16 | 2.5 | 2 | 8 | 0.12 to 4 | 85.6 | 0.25 to 8 | 91.1 | |

| AFG | ≤0.0312 to 1 | 0.04 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| CAS | ≤0.0312 to 8 | 0.05 | ≤0.0312 | 0.25 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| MFG | ≤0.0312 to 2 | 0.05 | ≤0.0312 | 0.0625 | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Overall agreement of methods (all antifungals) | 66.7 | 82.2 | |||||||

The GM and percent agreement were calculated only when there was a minimum of 5 isolates for a species. VRC, voriconazole; ITC, itraconazole; POS, posaconazole; AMB, amphotericin B; AFG, anidulafungin; CAS, caspofungin; MFG, micafungin; ND, not determined.

The percent agreement of the results obtained by the EUCAST method and with the YO panels after 48 h (YO48) and 72 h (YO72) is shown in Table 1. Overall, there was 67% agreement (95% confidence interval [CI], 62% to 72%) between the results obtained by the EUCAST method and with the YO panels when they were read at 48 h and 82% agreement (95% CI, 78% to 86%) when they were read at 72 h. The agreement was significantly different for different antifungals (Table 2), with the maximum agreement being observed for voriconazole and amphotericin B (93% and 91%, respectively, at 72 h). For all antifungals, most of the MIC values obtained with YO48 were noticeably lower than those obtained by the reference EUCAST method, and consequently, the percent agreement for voriconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, and amphotericin B when the results were read at 48 h was lower (74.4, 36.7, 70, and 85.6% agreement, respectively) than that when the results were read at 72 h (93.3, 56.7, 87.8, and 91.1% agreement, respectively). The worst correlation was detected for itraconazole in some species, and the lowest agreement with the reference method was detected for A. wyomingensis, i.e., 0% after 48 h and 72 h (Table 1). In contrast, agreement was 100% for all isolates of A. pseudoviridinutans, which had highly elevated MICs of this antifungal agent (MIC > 8 mg/liter), and for A. arcoverdensis (84.6%) after 72 h. Logistic regression results indicated that A. felis isolates had an eight times increased likelihood (odds ratio [OR], 8) of agreement between the results obtained by the EUCAST method and with the YO panels than A. wyomingensis isolates. The likelihood of agreement between the EUCAST method and the YO panels was the lowest for A. siamensis isolates and the highest for A. felis isolates (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Unconditional logistic regression analyses conducted to investigate agreement between EUCAST reference method and Sensititre YeastOne panel for different antifungals and speciesa

| Variable | 48 h |

72 h |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | LSM | SE | OR | 95% CI | LSM | SE | |

| Antifungals | ||||||||

| Amphotericin B | 2.03 | 0.97–4.43 | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.23–2.20 | 0.91 | 0.03 |

| Itraconazole | 0.20 | 0.10–0.37 | 0.37 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.03–0.22 | 0.57 | 0.05 |

| Posaconazole | 0.80 | 0.41–1.54 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.17–1.42 | 0.88 | 0.03 |

| Voriconazoleb | 1.00 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.03 | ||

| Speciesc | ||||||||

| A. felis | 10.68 | 5.15–23.22 | 0.85 | 0.03 | 8.33 | 3.57–21.38 | 0.93 | 0.03 |

| A. acrensis | 2.79 | 1.00–8.16 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 2.67 | 0.86–10.18 | 0.80 | 0.09 |

| A. arcoverdensis | 3.23 | 1.50–7.12 | 0.63 | 0.07 | 5.11 | 1.99–15.00 | 0.88 | 0.04 |

| A. siamensis | 1.11 | 0.21–5.00 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.15–3.06 | 0.50 | 0.18 |

| A. udagawae | 3.00 | 1.47–6.26 | 0.62 | 0.06 | 2.57 | 1.19–5.73 | 0.79 | 0.05 |

| A. wyomingensisb | 1.00 | 0.35 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 0.06 | ||

For the definition of agreement, see Materials and Methods. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LSM, least-squares mean; SE, standard error.

Reference categories for odds ratios.

The results for three species, A. pseudoviridinutans, A. viridinutans, and A. aureolus, were excluded from this analysis because of zero or low frequencies in cells of the contingency table of species with the agreement outcome.

The azole MIC data cross-tabulated in Table 3 indicate a correlation between the elevated MIC values of voriconazole and itraconazole, since 81 of 90 isolates had elevated MIC values of both drugs and the McNemar test result was significant (P < 0.001). In contrast, no correlation between the MIC values of the other azoles was observed (Table 3); 81 of 87 isolates with low MICs of posaconazole had elevated MICs of itraconazole, and 83 of 87 isolates with low MICs of posaconazole had elevated MICs of voriconazole. This lack of a correlation was confirmed by significant McNemar test results (P < 0.001) and very low kappa values (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Evaluation of cross-correlation of elevated MICs of azolesa

| Species | Antifungal agent | Kappa value (SE) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VRC | ITC | POS | ||

| All species | VRC | 1 | 0.15 (0.17) | 0.0032 (0.002) |

| ITC | 1 | 0.0049 (0.003) | ||

| POS | 1 | |||

| A. felis | VRC | 1 | −0.039 (0.027) | 0.003 (0.004) |

| ITC | 1 | 0.003 (0.004) | ||

| POS | 1 | |||

| A. udagawae | VRC | 1 | −0.097 (0.077) | 0.0078 (0.01) |

| ITC | 1 | 0.026 (0.03) | ||

| POS | 1 | |||

An elevated MIC value was defined as an MIC of ≥2 mg/liter. VRC, voriconazole; ITC, itraconazole; POS, posaconazole.

DISCUSSION

Our data show that species from the A. viridinutans species complex have variable MICs of amphotericin B and elevated MICs of itraconazole and voriconazole (Table 1). The most elevated MICs were observed for itraconazole, while almost all A. viridinutans species complex isolates had low MICs and MECs of posaconazole and echinocandins. Published clinical cases caused by A. viridinutans species complex isolates, the antifungal MICs (or MECs), and the clinical outcome of therapy are reviewed in Table 4. It was demonstrated that many representatives of the complex have elevated MICs of azoles (itraconazole and voriconazole) and amphotericin B (summarized in Table 4) (4, 5, 7–9, 14–31). Howard (32) reviewed data for some cryptic species and designated A. viridinutans and A. felis to be susceptible to amphotericin B, having reduced susceptibility to voriconazole and variable susceptibility to itraconazole, posaconazole, and echinocandins. The detection of elevated MICs of polyenes (amphotericin B), azoles (voriconazole, posaconazole, itraconazole), or echinocandins in A. fumigatus-like isolates during antifungal susceptibility testing may indicate the presence of cryptic species, as the majority of A. fumigatus isolates are susceptible to these antifungals (33, 34), although resistance to azoles has been increasingly reported in some countries (35). Most other investigators have reported low MECs of echinocandins, in accordance with our data (9, 14, 16, 18, 20, 21, 23, 26, 27), with the exception of Yaguchi et al. (7), who reported high MICs of micafungin obtained by the CLSI method (>16 mg/liter). Barrs et al. (9) examined the MICs of 13 A. felis isolates using YO48 and found MICs of itraconazole of less than 1 mg/liter (9). However, as shown in this study, a reading time after only 48 h is associated with a high degree of falsely low MICs (Table 1). Some other authors reported high MICs of itraconazole in isolates from the A. viridinutans complex, in agreement with the findings of our study (Table 4) (5, 16–18, 20, 24). Interestingly, we observed a paradoxical effect for itraconazole with YO48 and YO72 for many of the strains tested. According to the manufacturer's instructions (Trek Diagnostic Systems), this phenomenon should be ignored and the lower MIC should be recorded. However, according to our results, it seems that the phenomenon should not be ignored, because it may indicate elevated MICs of this antifungal.

TABLE 4.

Antifungal susceptibility, treatment response, and outcome for clinical isolates of A. viridinutans complex previously reporteda

| Species (no. of isolates) | MIC or MEC (mg/liter) |

Method | Antifungal agent (response to treatmentb) | Outcome | Reference(s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB | ITC | VRC | POS | AFG | CAS | MFG | |||||

| A. felis (1)c | 1 | 2 | >16 | CLSI | 7 | ||||||

| A. felis (2)d | 0.5 to 1 | 16 | 4 | 0.25 to 0.5 | 1 | 0.03 to 0.2 | CLSI | 16 | |||

| A. felis (1)e | 1 | >16 | 4 | 0.25 | ≤0.016 | ≤0.016 | CLSI | ITC (1), VRC (1), POS + CAS (1), POS (3, 1) | Died | 20 | |

| A. felis (13) | 0.25 to 1 | 0.03 to 1 | 0.25 to 4 | 0.03 to 1 | 0.015 | 0.008 to 2 | 0.008 to 0.015 | YO48 | 9 | ||

| A. felis (1)f | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | CLSI | MFG (1), VRC (1), AMB + CAS (1) | Poor | 24 | ||||

| A. felis (1)g | 0.064 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.064 | Etest | No treatment (1) | Died (cat) | 25 | |||

| A. felis (1) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.5 | <0.03 | 1 | <0.03 | EUCAST | AMB + CAS (1) | Died | 26, 28 |

| A. felis (5)h | 1 to 2 | 8 to >16 | 8 | CLSI | 12 | ||||||

| A. felis (1)/A. pseudoviridinutans (3)i | 0.5j | 2j | 4j | CLSI | 29 | ||||||

| A. felis (1) | 2 | 0.125 | 0.5 | EUCAST | VRC (1), AMB (1) | Died | 30 | ||||

| A. pseudoviridinutans (2)k | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | CLSI | VRC (1), POS + CAS (3) | Survived | 17 | ||

| 2 to 8 | 8 | 2 to 4 | ≤0.016 to 0.5 | 0.06 to 0.25 | VRC (1), AMB + CAS (1), POS (1), POS + CAS + 5FC (1) | Died | 17 | ||||

| A. pseudoviridinutans (1)l | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0.015 | CLSI | FLC + VRC (1), VRC + AMB + NAT + TER (1) | Survived (surgery) | 14 | |||

| A. udagawae (1) | >32 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | Etest | ITC + AMB (1), AMB + CAS (1) | Died (cat) | 19 | |||

| A. udagawae (3) | 1 to 2 | 0.25 to 2 | 0.5 to 2 | 0.125 to 0.25 | CLSI | 8 | |||||

| A. udagawae (4) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.25 | 1 | ≤0.015 | CLSI | VRC (1), VRC + CAS (1), POS (1), AMB + VRC (2), AMB (2), AMB + CAS (3) | Survived | 18 | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | ≤0.015 | ITC (1), POS (3) | Survived | 18 | |||

| 2 | 4 | >16 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.015 | POS (1), VRC + CAS (1), VRC + CAS + AMB + TER + 5FC (1) | Dissemination to brain, died | 18 | |||

| 0.5 to 1 | 1 | 1 to 4 | 0.5 | 0.25 to 0.5 | ≤0.015 | ITC(1), AMB (1), VRC + CAS (1), POS + MFG + AMB + TER (1), CAS (2), VRC + CAS (2) | Dissemination, died | 18 | |||

| A. udagawae (1) | 0.125 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.016 | 0.5 | 0.25 | CLSI | AMB (1), AMB + ITC (1), ITR (2) | Survived (surgery) | 21 |

| A. udagawae (1) | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.016 | CLSI | VRC (3) | Survived | 23 | |||

| A. udagawae (2) | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | CLSI | VRC + CAS (1) | Poor | 24 | ||||

| AMB + MFG + VRC (1) | Poor | 24 | |||||||||

| A. udagawae (1) | >32 | 0.25 | 1 | Etest | ITC (3) | Survived (cat) | 25 | ||||

| A. udagawae (5) | 0.05 to 4 | 0.25 to 1 | 2 to 4 | 0.12 to 0.25 | 0.03 to 0.06 | 0.03 to 2 | 0.03 to 0.12 | EUCAST | 27 | ||

| A. udagawae (9) | 1j | 0.5j | 8j | CLSI | 29 | ||||||

| A. udagawae (1) | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | CLSI | VOR (1) | Died | 31 | ||||

| A. viridinutans (1)m | 1 | 0.5 | >16 | CLSI | 7 | ||||||

| A. viridinutans (1)m | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | CLSI | 12 | ||||||

MEC, minimal effective concentration; AMB, amphotericin B; ITC, itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; POS, posaconazole; AFG, anidulafungin; CAS, caspofungin; MFG, micafungin; 5FC, flucytosine; TER, terbinafine; NAT, natamycin; YO48, Sensititre YeastOne panel after 48 h.

1, none/progressive disease; 2, weak response; 3, clinical improvement.

Isolate IFM 54303, originally listed as A. viridinutans, was reidentified in this study as A. felis.

Strains CM-3147 (= NRRL 62900 = CCF 4895) and CM-4518 (= NRRL 62902), listed as A. viridinutans in the original publication, are A. felis on the basis of current taxonomy.

This strain (NRRL 62901 = CM-5623 = CCF 4896 = CCF 4557) was later reidentified as A. felis by Barrs et al. (9) and was included in the present study.

This strain is A. felis on the basis of current taxonomy.

The strain, listed as A. viridinutans, is A. felis on the basis of current taxonomy.

Isolates of A. pseudofelis and A. parafelis were considered conspecific with A. felis in this study.

The A. viridinutans strains included in the study of Tamiya et al. (29) are A. felis (IFM 54303) and three strains of A. pseudoviridinutans (IFM 55266, IFM 59502, and IFM 59503); all strains were tested in the present study.

The value represents the MIC50.

Isolates NIHAV1 and NIHAV2, listed as A. viridinutans, were subsequently described as A. pseudoviridinutans by Sugui et al. (12).

This strain (IFM 59502), listed as A. viridinutans, was reidentified as A. pseudoviridinutans in the present study.

Ex-type strain of A. viridinutans.

The A. viridinutans species complex belongs to the section Fumigati, and morphological differentiation of these species from A. fumigatus, the most common agent of IA, requires expertise (2, 5, 8, 36). So-called cryptic species may remain unrecognized, especially in laboratories that still predominantly use only phenotypic identification. The frequency of cryptic section Fumigati species in clinical settings has been reported to be between 4 and 5% in some studies that used molecular methods for identification (2, 8). The recognition of cryptic species is important because some of them exhibit susceptibility profiles different from those of their well-known relatives. Cases of human and animal infections due to the A. viridinutans species complex reported previously were mostly attributed to A. udagawae, A. felis, and A. viridinutans (Table 4). The isolates responsible for many of these reported infections showed clinical resistance to antifungal therapy (Table 4), even though in vitro susceptibility testing showed low MICs of these antifungals (17, 18, 20). Some authors published descriptions of a positive clinical effect of therapy with posaconazole, posaconazole plus caspofungin, or amphotericin B plus caspofungin (17, 18, 20, 22). A case of human IA due to A. udagawae was successfully treated using voriconazole, and a feline infection was successfully treated using high doses of itraconazole (23, 25), while in other cases there was little or no effect when voriconazole or itraconazole was used for therapy (14, 17, 18, 20, 24, 25). Coelho et al. (20) reported clinical improvement when using posaconazole at the beginning of therapy, but later the therapy failed and the patient died. This could be due to either an advanced stage of infection or the development of resistance. The latter phenomenon is documented in A. fumigatus infections (37). Voriconazole is recommended for the first-line treatment of IA in humans (38), and when resistance to azoles is detected, therapy is switched to liposomal amphotericin B. If the rate of environmental resistance to A. fumigatus is high (≥10%) in the region, combinations of voriconazole with echinocandin or liposomal amphotericin B are favored as initial therapy (38). Due to the apparent low frequency of cryptic Aspergillus species recognized in clinical practice, there are no solid clinical data to guide therapy (39). However, as antifungal susceptibility varies largely among fungal isolates and species, in vitro susceptibility testing for every isolate of a cryptic species is essential.

Conclusions.

In this study, most A. viridinutans species complex isolates demonstrated elevated MICs of itraconazole and voriconazole in vitro, and susceptibility to amphotericin B was variable. In contrast, posaconazole and echinocandins had potent in vitro activity against A. viridinutans species complex isolates. There were no clear antifungal susceptibility patterns between species, and intraspecific variation was usually high. This fact highlights the need to use reliable methods for MIC determinations over correct identification to a species level. However, the identification to a level of species complex and differentiation from A. fumigatus are also important due to different susceptibility patterns. The agreement between the Senstititre YeastOne commercial method and the EUCAST method was high, especially for the most clinically important species in the A. viridinutans complex, i.e., A. felis, A. udagawae, and A. pseudoviridinutans, in contrast to infrequently pathogenic or nonpathogenic species, such as A. wyomingensis and A. siamensis. Better agreement between the methods was usually achieved with a reading time of 72 h than with one of 48 h. Importantly, however, the YeastOne panel frequently did not detect elevated MICs of itraconazole.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antifungal agents.

Anidulafungin and voriconazole in powder form were procured from Pfizer Pharmaceutical Group (New York, NY, USA), micafungin from Astellas Pharma Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), caspofungin and posaconazole from Merck Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories (Rahway, NJ, USA), and itraconazole and amphotericin B from Sigma-Aldrich (Prague, Czech Republic).

Organisms.

A total of 90 Aspergillus isolates from the A. viridinutans species complex were collected from various environmental and clinical sources worldwide. All the ex-type strains of currently described species in the A. viridinutans complex were also examined. Information on the isolation source of all isolates is provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Molecular methods.

An ArchivePure DNA yeast and Gram2+ kit (5 Prime Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used for DNA isolation from 7-day-old cultures according to the manufacturer's instructions, as updated by Hubka et al. (40). The calmodulin gene (CaM) was amplified using forward primer CF1M or CF1L and reverse primer CF4 (41). The PCR conditions were those described by Hubka et al. (42). PCR product purification followed the protocol of Réblová et al. (43). Automated sequencing was performed at the Macrogen Sequencing Service (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) using both terminal primers.

Sequences were inspected and assembled using the BioEdit (v.7.2.5) program (www.mbio.ncsu.edu/BioEdit/bioedit.html). Alignment was performed using the G-INS-i option implemented in the MAFFT (v.7) program (44). The alignment was trimmed and then analyzed using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses. The analyses involved 91 nucleotide sequences and 695 positions, of which 160 were variable and 104 were parsimony informative. Suitable partitioning scheme and substitution models (according to the Bayesian information criterion) for analyses were selected using the greedy strategy implemented in the PartitionFinder (v.1.1.1) program (45) with settings allowing introns, exons, and codon positions to be independent data sets. The optimal partitioning scheme for ML analysis divided the data set into four partitions with the following substitution models: K80+G substitution models were proposed for CaM introns, the F81 model was proposed for the 1st codon positions, the F81 model was proposed for the 2nd codon positions, and the HKY model was proposed for the 3rd codon positions. The ML tree was constructed with the IQ-TREE (v.1.4.4) program (46), with nodal support being determined by nonparametric bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates. Aspergillus lentulus NRRL 35552 was used as the outgroup. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated using the MrBayes (v.3.2.6) program (47). Optimal partitioning scheme and substitution models were selected as described above. The optimal partitioning scheme for BI analysis divided the data set into four partitions with the following substitution models: K80+G substitution models were proposed for CaM introns, the F81 model was proposed for the 1st codon positions, the F81 model was proposed for the 2nd codon positions, and the HKY model was proposed for the 3rd codon positions. The analyses ran for 107 generations, two parallel runs with four chains each were used, every 1,000th tree was retained, and the first 25% of the trees was discarded as burn-in.

Susceptibility testing.

The broth microdilution method was performed according to EUCAST document E.Def 9.3 (48). The isolates were incubated at 35°C on potato dextrose agar (Trios, Prague, Czech Republic). Inoculum suspensions were prepared from 7- to 14-day-old colonies (to achieve acceptable sporulation), the suspensions were filtered using sterile nylon filters with an 11-μm pore size (Merck, Prague, Czech Republic), and a spectrophotometer (model Spekol 11; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used to adjust the suspension to a concentration of 2 × 106 to 5 × 106 conidia/ml (optical density, 0.09 to 0.11), equivalent to a McFarland 0.5 standard. Microplates were incubated at 35°C in ambient air for 48 h. MICs were determined for amphotericin B and the azoles, and minimum effective concentrations (MECs) were determined for the echinocandins.

Assays with Sensititre YeastOne (YO) panels (Trek Diagnostic System Ltd., East Grinstead, UK) were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The MICs for Aspergillus species were determined to be the lowest concentration with a blue color. The MICs of amphotericin B, voriconazole, itraconazole, and posaconazole were evaluated with YO panels after 48 h (YO48) and after 72 h (YO72) of incubation. Echinocandins were not evaluated with the YO panels because MEC endpoints should be determined after 24 h according to the manufacturer's instructions. Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and Candida krusei ATCC 6258 were used as quality control strains.

Data analysis.

For the EUCAST method, MIC ranges and the corresponding GM MIC values were determined for each species, antifungal drug, and incubation time. The MIC50s and MIC90s were determined for species represented by at least five isolates in our data set. Discrepancies among MIC endpoints of no more than 2-fold dilutions were used to calculate the percent agreement that was determined for each combination of isolate, drug, and incubation time for species represented by at least five isolates in our data set.

Statistical analysis.

Descriptive statistics were calculated using Microsoft Excel software. Further statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (v.9.4) software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.). For GM MIC calculation, MIC values of <0.015 mg/liter were set at 0.008 mg/liter and MIC values of >16 mg/liter were set at 32 mg/liter, while MEC values of <0.008 mg/liter were set at 0.004 mg/liter and MEC values of >8 mg/liter were set at 16 mg/liter. For calculation of agreement between the results obtained with the YO panel and by the EUCAST method, extreme values were treated similarly. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to evaluate differences in agreement between species and antifungals. Odds ratios (ORs), their 95% confidence intervals, least-squares means, and standard errors were determined. The correlation of elevated MIC values between azoles was tested by analyzing the MIC values for each pair of antifungal drugs. For this purpose, since no interpretive breakpoints are established, elevated MIC values were defined as MICs of ≥2 mg/liter. A cross-correlation between the MICs of different azoles was estimated by cross-tabulating the data, conducting McNemar tests, and calculating kappa statistics. All P values reported here are two-sided. Differences were considered statistically significant at a P value of ≤0.05.

Accession number(s).

The sequences generated in this study were deposited into the EMBL (European Molecular Biology Laboratory) database under the accession numbers listed in Table S1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the projects of the Charles University Grant Agency (GAUK 1130214), Charles University Research Centre program no. 204069, and project BIOCEV (CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0109), provided by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic and ERDF. Additional support was obtained from research grant no. IGA_LF_2017_031 and RVO: 61989592 (Palacky University, Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic), and by a Thompson Fellowship from the University of Sydney.

We thank Milada Chudíčková and Alena Gabrielová for their invaluable assistance in the laboratory and Alena Nováková, Alena Kubátová, Stephen W. Peterson, Mark Wilson, Adrian Zelazny, and Maria Dolores Pinheiro for providing some cultures. We also thank Pfizer Pharmaceutical Group (New York, NY, USA) for providing voriconazole and anidulafungin, Astellas Pharma Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) for providing micafungin, and Merck Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories (Rahway, NJ, USA) for providing caspofungin and posaconazole.

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01927-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin SJ, Schranz J, Teutsch SM. 2001. Aspergillosis case-fatality rate: systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 32:358–366. doi: 10.1086/318483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Mellado E, Peláez T, Pemán J, Zapico S, Alvarez M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Cuenca-Estrella M, FILPOP Study Group. 2013. Population-based survey of filamentous fungi and antifungal resistance in Spain (FILPOP study). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3380–3387. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00383-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamoth F. 2016. Aspergillus fumigatus-related species in clinical practice. Front Microbiol 7:683. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balajee SA, Gribskov JL, Hanley E, Nickle D, Marr KA. 2005. Aspergillus lentulus sp. nov., a new sibling species of A. fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 4:625–632. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.3.625-632.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugui JA, Vinh DC, Nardone G, Shea YR, Chang YC, Zelazny AM, Marr KA, Holland SM, Kwon-Chung KJ. 2010. Neosartorya udagawae (Aspergillus udagawae), an emerging agent of aspergillosis: how different is it from Aspergillus fumigatus? J Clin Microbiol 48:220–228. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01556-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nováková A, Hubka V, Dudová Z, Matsuzawa T, Kubátová A, Yaguchi T, Kolařík M. 2014. New species in Aspergillus section Fumigati from reclamation sites in Wyoming (USA) and revision of A. viridinutans complex. Fungal Divers 64:253–274. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0262-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yaguchi T, Horie Y, Tanaka R, Matsuzawa T, Ito J, Nishimura K. 2007. Molecular phylogenetics of multiple genes on Aspergillus section Fumigati isolated from clinical specimens in Japan. Jpn J Med Mycol 48:37–46. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.48.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balajee SA, Kano R, Baddley JW, Moser SA, Marr KA, Alexander BD, Andes D, Kontoyiannis DP, Perrone G, Peterson S, Brandt ME, Pappas PG, Chiller T. 2009. Molecular identification of Aspergillus species collected for the transplant-associated infection surveillance network. J Clin Microbiol 47:3138–3141. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01070-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrs VR, van Doorn TM, Houbraken J, Kidd SE, Martin P, Pinheiro MD, Richardson M, Varga J, Samson RA. 2013. Aspergillus felis sp. nov., an emerging agent of invasive aspergillosis in humans, cats, and dogs. PLoS One 8:e64871. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eamvijarn A, Manoch L, Chamswarng C, Piasai O, Visarathanonth N, Luangsaard JJ, Kijjoa A. 2013. Aspergillus siamensis sp. nov. from soil in Thailand. Mycoscience 54:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2013.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrs V, Beatty J, Dhand NK, Talbot J, Bell E, Abraham L, Chapman P, Bennett S, van Doorn T, Makara M. 2014. Computed tomographic features of feline sino-nasal and sino-orbital aspergillosis. Vet J 201:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sugui JA, Peterson SW, Figat A, Hansen B, Samson RA, Mellado E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Kwon-Chung KJ. 2014. Genetic relatedness versus biological compatibility between Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. J Clin Microbiol 52:3707–3721. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01704-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsuzawa T, Takaki GMC, Yaguchi T, Okada K, Abliz P, Gonoi T, Horie Y. 2015. Aspergillus arcoverdensis, a new species of Aspergillus section Fumigati isolated from Caatinga soil in state of Pernambuco, Brazil. Mycoscience 56:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2014.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shigeyasu C, Yamada M, Nakamura N, Mizuno Y, Sato T, Yaguchi T. 2012. Keratomycosis caused by Aspergillus viridinutans: an Aspergillus fumigatus-resembling mold presenting distinct clinical and antifungal susceptibility patterns. Med Mycol 50:525–528. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.658875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz ME, Dougall AM, Weeks K, Cheetham BF. 2005. Multiple genetically distinct groups revealed among clinical isolates identified as atypical Aspergillus fumigatus. J Clin Microbiol 43:551–555. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.551-555.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alcazar-Fuoli L, Mellado E, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL. 2008. Aspergillus section Fumigati: antifungal susceptibility patterns and sequence-based identification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:1244–1251. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00942-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinh DC, Shea YR, Jones PA, Freeman AF, Zelazny A, Holland SM. 2009. Chronic invasive aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus viridinutans. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1292–1294. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.090251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinh DC, Shea YR, Sugui JA, Parrilla-Castellar ER, Freeman AF, Campbell JW, Pittaluga S, Jones PA, Zelazny A, Kleiner D, Kwon-Chung KJ, Holland SM. 2009. Invasive aspergillosis due to Neosartorya udagawae. Clin Infect Dis 49:102–111. doi: 10.1086/599345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kano R, Itamoto K, Okuda M, Inokuma H, Hasegawa A, Balajee SA. 2008. Isolation of Aspergillus udagawae from a fatal case of feline orbital aspergillosis. Mycoses 51:360–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coelho D, Silva S, Vale-Silva L, Gomes H, Pinto E, Sarmento A, Pinheiro MD. 2011. Aspergillus viridinutans: an agent of adult chronic invasive aspergillosis. Med Mycol 49:755–759. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.556672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posteraro B, Mattei R, Trivella F, Maffei A, Torre A, De Carolis E, Posteraro P, Fadda G, Sanguinetti M. 2011. Uncommon Neosartorya udagawae fungus as a causative agent of severe corneal infection. J Clin Microbiol 49:2357–2360. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00134-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrs VR, Halliday C, Martin P, Wilson B, Krockenberger M, Gunew M, Bennett S, Koehlmeyer E, Thompson A, Fliegner R, Hocking A, Sleiman S, O'Brien C, Beatty JA. 2012. Sinonasal and sino-orbital aspergillosis in 23 cats: aetiology, clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes. Vet J 191:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gyotoku H, Izumikawa K, Ikeda H, Takazono T, Morinaga Y, Nakamura S, Imamura Y, Nishino T, Miyazaki T, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, Yasuoka A, Yaguchi T, Ohno H, Miyzaki Y, Kamei K, Kanda T, Kohno S. 2012. A case of bronchial aspergillosis caused by Aspergillus udagawae and its mycological features. Med Mycol 50:631–636. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2011.639036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escribano P, Peláez T, Muñoz P, Bouza E, Guinea J. 2013. Is azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus a problem in Spain? Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2815–2820. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02487-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kano R, Shibahashi A, Fujino Y, Sakai H, Mori T, Tsujimoto H, Yanai T, Hasegawa A. 2013. Two cases of feline orbital aspergillosis due to Aspergillus udagawae and A. viridinutans. J Vet Med Sci 75:7–10. doi: 10.1292/jvms.12-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelaez T, Alvarez-Perez S, Mellado E, Serrano D, Valerio M, Blanco JL, Garcia ME, Munoz P, Cuenca-Estrella M, Bouza E. 2013. Invasive aspergillosis caused by cryptic Aspergillus species: a report of two consecutive episodes in a patient with leukaemia. J Med Microbiol 62:474–478. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.044867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Alcazar-Fuoli L, Cuenca-Estrella M. 2014. Antifungal susceptibility profile of cryptic species of Aspergillus. Mycopathologia 178:427–433. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9775-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Álvarez-Pérez S, Mellado E, Serrano D, Blanco JL, Garcia ME, Kwon M, Munoz P, Cuenca-Estrella M, Bouza E, Peláez T. 2014. Polyphasic characterization of fungal isolates from a published case of invasive aspergillosis reveals misidentification of Aspergillus felis as Aspergillus viridinutans. J Med Microbiol 63:617–619. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.068502-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamiya H, Ochiai E, Kikuchi K, Yahiro M, Toyotome T, Watanabe A, Yaguchi T, Kamei K. 2015. Secondary metabolite profiles and antifungal drug susceptibility of Aspergillus fumigatus and closely related species, Aspergillus lentulus, Aspergillus udagawae, and Aspergillus viridinutans. J Infect Chemother 21:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chong GM, Vonk AG, Meis JF, Dingemans GJH, Houbraken J, Hagen F, Gaajetaan GR, van Tegelen DWE, Simons GFM, Rijnders BJA. 2017. Interspecies discrimination of A. fumigatus and siblings A. lentulus and A. felis of the Aspergillus section Fumigati using the AsperGenius® assay. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 87:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seki A, Yoshida A, Matsuda Y, Kawata M, Nishimura T, Tanaka J, Misawa Y, Nakano Y, Asami R, Chida K, Kikuchi K, Arai T. 2017. Fatal fungal endocarditis by Aspergillus udagawae: an emerging cause of invasive aspergillosis. Cardiovasc Pathol 28:14–17. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howard SJ. 2014. Multi-resistant aspergillosis due to cryptic species. Mycopathologia 178:435–439. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diekema DJ, Messer SA, Hollis RJ, Jones RN, Pfaller MA. 2003. Activities of caspofungin, itraconazole, posaconazole, ravuconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against 448 recent clinical isolates of filamentous fungi. J Clin Microbiol 41:3623–3626. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3623-3626.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sabatelli F, Patel R, Mann PA, Mendrick CA, Norris CC, Hare R, Loebenberg D, Black TA, McNicholas PM. 2006. In vitro activities of posaconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against a large collection of clinically important molds and yeasts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2009–2015. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00163-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Linden JW, Arendrup MC, Warris A, Lagrou K, Pelloux H, Hauser PM, Chryssanthou E, Mellado E, Kidd SE, Tortorano AM, Dannaoui E, Gaustad P, Baddley JW, Uekötter A, Lass-Flörl C, Klimko N, Moore CB, Denning DW, Pasqualotto AC, Kibbler C, Arikan-Akdagli S, Andes D, Meletiadis J, Naumiuk L, Nucci M, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2015. Prospective multicenter international surveillance of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1041–1044. doi: 10.3201/eid2106.140717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gautier M, Normand AC, Ranque S. 2016. Previously unknown species of Aspergillus. Clin Microbiol Infect 22:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verweij PE, Zhang J, Debets AJ, Meis JF, van de Veerdonk FL, Schoustra SE, Zwaan BJ, Melchers WJ. 2016. In-host adaptation and acquired triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a dilemma for clinical management. Lancet Infect Dis 16:e251–e260. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verweij PE, Ananda-Rajah M, Andes D, Arendrup MC, Brüggemann RJ, Chowdhary A, Cornely OA, Denning DW, Groll AH, Izumikawa K, Kullberg BJ, Lagrou K, Maertens J, Meis JF, Newton P, Page I, Seyedmousavi S, Sheppard DC, Viscoli C, Warris A, Donnelly JP. 2015. International expert opinion on the management of infection caused by azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus. Drug Resist Updat 21:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nedel WL, Pasqualotto AC. 2014. Treatment of infections by cryptic Aspergillus species. Mycopathologia 178:441–445. doi: 10.1007/s11046-014-9811-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubka V, Nováková A, Kolařík M, Jurjević Ž, Peterson SW. 2015. Revision of Aspergillus section Flavipedes: seven new species and proposal of section Jani sect. nov. Mycologia 107:169–208. doi: 10.3852/14-059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson SW. 2008. Phylogenetic analysis of Aspergillus species using DNA sequences from four loci. Mycologia 100:205–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hubka V, Lyskova P, Frisvad JC, Peterson SW, Skorepova M, Kolarik M. 2014. Aspergillus pragensis sp. nov. discovered during molecular re-identification of clinical isolates belonging to Aspergillus section Candidi. Med Mycol 52:565–576. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myu022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Réblová M, Hubka V, Thureborn O, Lundberg J, Sallstedt T, Wedin M, Ivarsson M. 2016. From the tunnels into the treetops: new lineages of black yeasts from biofilm in the Stockholm metro system and their relatives among ant-associated fungi in the Chaetothyriales. PLoS One 11:e0163396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SY, Guindon S. 2012. PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol 29:1695–1701. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol 61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arendrup MC, Guinea J, Cuenca-Estrella M, Meletiadis J, Mouton JW, Lagrou K, Howard SJ, and the Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). 2015. EUCAST method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for conidia forming moulds version 9.3. EUCAST, Växjö, Sweden, https://www.aspergillus.org.uk/sites/default/files/pictures/Lab_protocols/EUCAST_E_Def_9_3_Mould_testing_definitive_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hubka V, Barrs V, Dudová Z, Sklenář F, Kubátová A, Matsuzawa T, Yaguchi T, Horie Y, Nováková A, Frisvad JC, Talbot JJ, Kolařík M. Unravelling species boundaries in the Aspergillus viridinutans complex (section Fumigati): opportunistic human and animal pathogens capable of interspecific hybridization. Persoonia, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.