Abstract

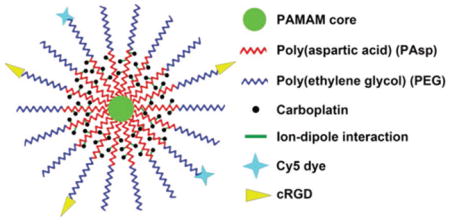

Platinum-based chemotherapy has been widely used to treat cancers including ovarian cancer; however, it suffers from dose-limiting toxicity. Judiciously designed drug nanocarriers can enhance the anticancer efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy while reducing its systemic toxicity. Herein the authors report a stable and water-soluble unimolecular nanoparticle constructed from a hydrophilic multi-arm star block copolymer poly(amidoamine)-b-poly(aspartic acid)-b-poly(ethylene glycol) (PAMAM-PAsp-PEG) conjugated with both cRGD (cyclo(Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Cys) peptide and cyanine5 (Cy5) fluorescent dye as a platinum-based drug nanocarrier for targeted ovarian cancer therapy. Carboplatin is complexed to the poly(aspartic acid) inner shell via pH-responsive ion–dipole interactions between carboplatin and the carboxylate groups of poly(aspartic acid). Based on flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning microscopy analyses, cRGD-conjugated unimolecular nanoparticles exhibit much higher cellular uptake by ovarian cancer cells overexpressing αvβ3 integrin than nontargeted (i.e., cRGD-lacking) ones. Carboplatin-complexed cRGD-conjugated nanoparticles also exhibit higher cytotoxicity than nontargeted nanoparticles as well as free carboplatin, while empty unimolecular nanoparticles show no cytotoxicity. These results indicate that stable unimolecular nanoparticles made of individual hydrophilic multi-arm star block copolymer molecules conjugate with tumor-targeting ligands and dyes (i.e., PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-cRGD/Cy5) are promising nanocarriers for platinum-based anticancer drugs for targeted cancer therapy.

Keywords: cancer chemotherapy, platinum-based drugs, targeted drug delivery, unimolecular nanoparticle

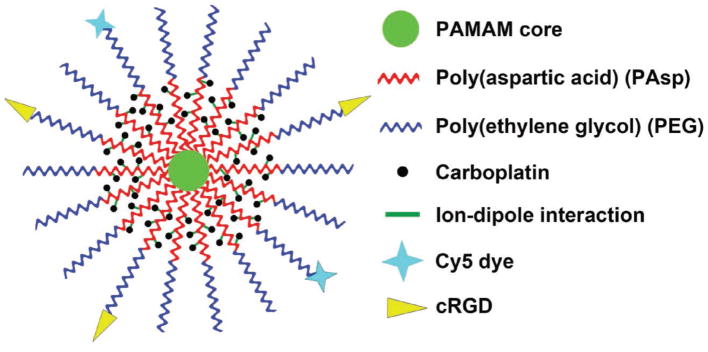

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the seventh most common cancer among women and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among American women.[1] The overall five-year survival rate is 45% in the U.S.[2] These poor outcomes may be attributed to a number of factors, including difficulties in early diagnosis, ease of metastasis, and lack of effective treatment modalities.[3,4] Platinum-based anticancer drugs, such as cisplatin and carboplatin have been widely used to treat various types of cancers clinically, including ovarian cancer.[5–7] However, their utility is limited due to their lack of tumor-targeting abilities,[8,9] low chemical stability (e.g., cisplatin),[10] and poor cellular uptake (e.g., carboplatin),[11,12] as well as their tendency to trigger multi-drug resistance in cancer therapy,[13,14] thereby leading to compromised treatment efficacy and undesirable side effects. All of these challenges can be potentially addressed by judiciously engineered drug nanocarriers.

Drug nanocarriers are desirable for targeted cancer therapy because they can offer both passive and active tumor targeting abilities.[15] Their passive tumor targeting ability is attributed to the enhanced permeability and retention effect.[15,16] Their active tumor targeting ability can be achieved by conjugating ligands on the surface of the nanocarriers that can locate and bind specifically with the receptors overexpressed by the cancer cells.[17,18] In addition, drug nanocarriers can also improve the chemical stability of the encapsulated drug,[19] enhance the cellular uptake of the drug,[11,12] and potentially reduce multi-drug resistance,[20,21] because, unlike free/pure drug, drug nanocarriers are taken up by the cancer cells via endocytosis.

Taking advantage of the desirable characteristics of drug nanocarriers, a number of platinum-based drug nanocarriers have been developed including functionalized inorganic nanoparticles,[22] polymer micelles,[23–25] and vesicles.[26,27] Using the interactions between the platinum (II) atoms and carboxylic groups, poly(methacrylic acid)-coated iron oxide nanoparticles were used to deliver carboplatin.[22] Furthermore, polymeric nanoparticles were also used for the delivery of platinum-based drugs. For example, cisplatin was incorporated into polymeric micelles based on the coordination bonds between the platinum (II) atoms and the pendent carboxylic groups of the polymer chains.[23,25] Cisplatin was also delivered using polymer vesicles to kill the cancer cells in vitro.[26,27] However, the stability of these conventional polymeric micelles or vesicles, both of which are self-assembled from a large number of amphiphilic linear molecules, is affected by a number of factors in vivo including the type and concentration of ions, concentration of the polymers, interactions with serum proteins, and flow stress. Premature disassociation in the blood stream can result in burst drug release, undermining their in vivo tumor targeting capabilities and causing undesirable side effects.[28–30]

Multifunctional unimolecular micelles, formed by individual multi-arm star amphiphilic block copolymer molecules, have been explored as drug nanocarriers for a number of drugs for targeted cancer therapy.[28,29,31–35] In contrast to other commonly investigated drug nanocarriers such as liposomes, polymer micelles and vesicles are self-assembled from a large number of amphiphilic linear molecules. Unimolecular micelles offer a number of advantages, including excellent stability in vitro and in vivo due to their covalent nature that makes them insensitive to polymer concentration, pH, or interaction with other bio-molecules such as serum proteins, a narrower size distribution, a potentially higher drug loading capacity, and a better control of the number of tumor targeting ligands or other agents (e.g., dye molecules) per nanoparticle.[36,37] These properties make unimolecular micelles preferable for both in vitro and in vivo applications.

Small hydrophobic drugs are typically loaded into the hydrophobic cores of the unimolecular micelles through hydrophobic interaction and hydrogen bonding. In contrast, platinum-based drugs are loaded into the drug nanocarriers mostly via an ion–dipole interaction or ionic complexation,[22,38] thus new designs of unimolecular nanoparticles are needed for platinum-based drug delivery. Although a number of unimolecular micelles have been reported as nanocarriers for small hydrophobic drugs, reports on unimolecular nanoparticles for platinum-based drug delivery were not found.

Herein, a multifunctional water soluble unimolecular nanoparticle was designed as a nanocarrier for platinum-based drugs for targeted cancer therapy using ovarian cancer as a model. As shown in Scheme 1, the unimolecular nanoparticle was formed by a water soluble multi-arm star block copolymer poly(amidoamine)-b-poly(aspartic acid)-b-poly(ethylene glycol) (PAMAM-PAsp-PEG). cRGD (cyclo(Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Cys) peptide and cyanine5 (Cy5) were selectively conjugated onto the distal ends of PEG, thereby enabling active tumor targeting as well as fluorescence imaging, respectively. αvβ3 integrin plays a key role in both tumor development and tumor metastasis, and it is overexpressed on both the tumor cells and the angiogenic endothelial cells of many types of solid tumors including ovarian, glioblastoma, melanoma, prostate, and breast cancers.[39,40] Furthermore, αvβ3 integrin is also upregulated in tumors following radiotherapy.[41] Strategies to simultaneously kill the tumor neovasculature as well as the tumor cells are highly desirable for targeted cancer therapy. Previous studies demonstrated that cRGD can efficiently target αvβ3 integrin-expressing tumor neovasculature and/or cells.[40,42] The anticancer drug, carboplatin, was complexed into the nanoparticles through a pH-responsive intermolecular ion–dipole interaction.[22] The resulting carboplatin-complexed cRGD-conjugated unimolecular nanoparticles exhibited high aqueous stability, pH-controlled carboplatin release behavior, higher cellular uptake by ovarian cancer cells, and higher cyto-toxicity than nontargeted nanoparticles, as well as free carboplatin. In addition to carboplatin, this unique unimolecular nanoparticle can also be used to deliver other types of platinum-based drugs such as cisplatin, thereby making it a promising nanoplatform for targeted cancer therapies, including ovarian cancer.

Scheme 1.

Illustration of the carboplatin-complexed unimolecular nanoparticles for targeted ovarian cancer therapy.

2. Experiment Section

2.1. Materials

Carboxyl-terminated fourth generation polyamidoamine dendrimer (PAMAM-COOH) (10 wt% in H2O), tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP·HCl), β-benzyl L-aspartate (BLA), Traut’s reagent (2-iminothiolane), sodium bicarbonate powder, and bovine insulin solution were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, USA. Heterobifunctional poly(ethylene glycol) derivatives, including NH2-PEG-maleimide (NH2-PEG-Mal) (molecular weight (Mw): 5000 g mol−1) and NH2-PEG-OCH3 (Mw: 5000 g mol−1), were acquired from JenKem Technology, USA. Cyanine5 amine (Cy5-NH2), a reactive dye, was purchased from Lumiprobe, USA. cyclo(Arg-Gly-Asp-D-Phe-Cys) peptide (cRGD) was bought from Peptides International, USA. N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS) and 1,3-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) were purchased from Acros, USA. Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium 1640 containing phenol red and L-glutamine was purchased from Corning, USA, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4), sodium pyruvate (100 × 10−6 M), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (1 M), trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (trypsin-EDTA) (0.25%), glucose (200 g L−1), Pen/Strep, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Invitrogen, USA. The OVCAR-3 human ovarian carcinoma cells were cultured in a medium prepared by mixing 500 mL RPMI medium 1640, 100 mL FBS, 5 mL sodium pyruvate, 5 mL Pen/Strep, 5 mL HEPES, 10 mL 7.5% sodium bicarbonate, 0.5 mL bovine insulin, and 2.8 mL glucose.

2.2. Synthesis of cRGD-PEG5000-NH2

cRGD peptide (14 mg, 0.05 mmol) and TCEP·HCl (3 mg, 0.01 mmol), a reducing agent, were dissolved in 5 mL deionized water (DI water) at room temperature. Then, 20 mg (0.004 mmol) Mal-PEG5000-NH2 was added to this solution. After the pH of this reaction mixture was adjusted to 6.5, the reaction was carried out under room temperature overnight. The product was purified by dialysis against DI water (molecular weight cut-off (MWCO): 15 kDa) and dried by lyophilization. The product, cRGD-PEG5000-NH2, was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-D6): 7.54–8.50 (18 H, m, cRGD), 3.48–3.50 (450 H, s, OCH2CH2) ppm.

2.3. Synthesis of Cy5-PEG5000-NH2

Each Cy5-NH2 molecule was first modified with one thiol group using Traut’s reagent. To carry out this reaction, 3.2 mg (0.0048 mmol) of Cy5-NH2 dye and 6.5 mg (0.048 mmol) Traut’s reagent were dissolved in a mixture of 1 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 1 mL DI water. A clear solution was formed after the agents dissolved completely in the mixture of solvents and the pH of the resulting reaction solution was adjusted to 8.5 by adding NaOH (1 M) dropwise. The reaction solution was then stirred at room temperature for 4 h. Thereafter, 14 mg (0.05 mmol) of TCEP·HCl, a reducing agent used to remove excessive Traut’s reagent in the system, and 20 mg (0.004 mmol) of Mal-PEG5000-NH2 were added into the above solution whose pH was then adjusted to 6.5 by adding HCl (1 M) dropwise. Further reaction was carried out at room temperature overnight. The product was purified by dialysis against DI water to remove DMSO and other small molecules, and then freeze-dried. The product, Cy5-PEG5000-NH2, was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-D6): 7.90–8.12 (12 H, m, Cy5), 3.48–3.50 (450 H, s, OCH2CH2) ppm.

2.4. Synthesis of β-Benzyl L-Aspartate N-Carboxyanhydride (BLA-NCA)

6.5 g (30 mmol) of BLA was suspended in 40 mL of anhydrous THF at room temperature. Into this solution, 4.5 g (15 mmol) of triphosgene in 10 mL anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) was added drop-wise. Then, the mixture was stirred at 55 °C under nitrogen for about 3 h until a clear solution was observed. Thereafter, the solvent was removed under vacuum and the product, BLA-NCA, was purified by recrystallization using a mixture of THF and hexane (1:1, v/v). The structure of BLA-NCA was confirmed by 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): 7.45–7.3 (5H, m, Ar-H), 6.2 (1H, s, NH), 5.2 (2H, s, CH2), 4.61 (1H, t, CH), and 2.85 (2H, t, CH2) ppm.

2.5. Synthesis of poly(β-benzyl L-aspartate)-poly(ethylene glycol) (PBLA-PEG)

The PEG-PBLA block copolymer was prepared by ring-opening polymerization. Typically, 50 mg (0.02 mmol) PEG-NH2 (NH2-PEG-OCH3, cRGD-PEG-NH2, or Cy5-PEG-NH2), and 115 mg (0.88 mmol) of BLA-NCA were dissolved in 5 mL anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF). The mixture was stirred at 55 °C for 72 h, after that the product was isolated by precipitation in cold diethyl ether three times and dried under vacuum. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-D6): 7.26–7.38 (106 H, m, Ar-H), 5.00–5.10 (46 H, s, CH2-Ar), 4.55–4.68 (21 H, m, NHCHCO), 3.35–3.53 (450 H, m, CH2CH2O from PEG), 2.48–2.90 (45 H, m, COCH2CH) ppm.

2.6. Synthesis of PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-OCH3/cRGD/Cy5

To prepare PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-OCH3/cRGD/Cy5, 1.25 mg (0.0001 mmol) of PAMAM-COOH (G4 with 64 carboxyl terminal groups) and three types of PBLA-PEG block copolymers—namely, cRGD-PEG-PBLA (14.3 mg, 0.00154 mmol), Cy5-PEG-PBLA (7.15 mg, 0.000768 mmol), and CH3O-PEG-PBLA (50.1 mg, 0.0054 mmol)—were dissolved in 5 mL DMF. DCC (1.90 mg, 0.009 mmol) and NHS (1.0 mg, 0.009 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture that was stirred at room temperature. After 24 h, the solution was purified by dialysis against DI water (MWCO 15 kDa). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-D6): 7.70–8.40 (7 H, m, cRGD), 7.30–7.10 (103 H, m, Ar-H), 4.90–5.00 (42 H, s, CH2-Ar), 4.60–4.50 (18 H, m, NHCHCO), 3.22–3.36 (450 H, m, CH2CH2O from PEG), 2.50–2.80 (40 H, m, COCH2CH) ppm. PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-OCH3/Cy5 was prepared following a similar method.

2.7. Synthesis of PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/cRGD/Cy5

First, the benzyl groups on the PBLA block in the PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-OCH3/cRGD/Cy5 multi-arm star copolymer was removed by alkaline hydrolysis. 1 M NaOH aqueous solution was added to PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-OCH3/cRGD/Cy5 dispersed in DI water dropwise to form a solution with a final NaOH concentration of 0.5 M. After 4 h, the solution became clear and its pH was adjusted to neutral by 1 M HCl. The final product was obtained after dialysis (MWCO 15 kDa) against DI water and lyophilization. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): 7.70–8.00 (8 H, m, cRGD), 4.60–4.50 (21 H, m, NHCHCO), 3.58–3.69 (450 H, m, CH2CH2O from PEG), 2.60–2.86 (46 H, m, COCH2CH) ppm. PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5 was prepared following a similar method.

2.8. Preparation of Carboplatin-Complexed Targeted Unimolecular Nanoparticles

A carboplatin solution was prepared by dissolving 0.92 mg of carboplatin in 2 mL DI water under stirring. The PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/cRGD/Cy5 polymer solution prepared by dissolving 3 mg of the polymer in 1 mL DI water followed by pH adjustment (pH of 7) was slowly added to the carboplatin solution and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Thereafter, the solution was dialyzed against DI water and lyophilized. The carboplatin-complexed nontargeted nanoparticles were prepared following a similar method using PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5.

To determine the drug loading level of carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles, 0.3 mg carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles were dissolved in 3 mL DI water. The pH of the resulting solution was adjusted to 3 and was stirred at room temperature for 48 h to allow complete release of carboplatin from the nanoparticles. The carboplatin loading level was determined by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a C-18 column with a mobile phase comprised of 50:50 water:acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.6 mL min−1. The UV-absorbance peak located at 227 nm was used to quantify the carboplatin concentration.[43] The carboplatin loading level was also determined by a Perkin Elmer Optima 2000 inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) at the wavelength of 265.945 nm as detailed in the Supporting Information.[44–46]

2.9. Characterization

The 1H NMR spectra were collected on a Bruker Advance 400 NMR spectrometer at 400 MHz using CDCl3, DMSO-D6, or D2O as the solvent and 0.5% tetramethylsilane as the internal standard. The hydrodynamic size and size distribution of the nanoparticles were characterized by a dynamic light scattering (DLS) spectrometer Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS at a 90° detection angle; the zeta-potential study was also performed by Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS. The concentration of the polymer solution used for the DLS measurement was 0.1 mg mL−1. Molecular weights of the multi-arm star copolymers were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) with triple detectors, including a refractive index detector, a viscometer detector, and a light scattering detector (Viscotek, USA). DMF was used as a mobile phase with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Tecnai TF-30, FEI company, USA) was used to observe the morphology and particle size of the dried nanoparticles. To prepare the TEM samples, a drop of unimolecular nanoparticles (0.05 mg mL−1) containing 0.8 wt% phosphotungstic acid was deposited onto a 200 mesh copper grid coated with carbon and dried at room temperature.

2.10. In Vitro Drug Release Study

Carboplatin release studies were performed in a glass apparatus at 37 °C in an acetate buffer (pH 5.5) or phosphate sodium buffer (PBS buffer) (pH 7.4) medium. First, 30 mg of carboplatin complexed PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD unimolecular nanoparticles were dispersed in 5 mL of medium and placed in a dialysis bag with a MWCO of 2 kDa. The dialysis bag was then immersed in 25 mL of release medium and kept in a horizontal laboratory shaker at a constant temperature of 37 °C at a stirring rate of 100 rpm. Samples (2 mL) were periodically collected and replaced by the same volume of fresh medium. The amounts of released drug were analyzed by HPLC. The drug release studies were performed in triplicate.

2.11. Cellular Uptake Assays

Cellular uptake experiments were performed using flow cytometry and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). For flow cytometry, OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells (6.25 × 104 cells cm−2) were seeded in 6-well culture plates and grown overnight. The cells were then treated with either targeted (cRGD-conjugated) or nontargeted (cRGD-lacking) nanoparticles (400 μg mL−1), pure medium (i.e., the control group), or a combination of cRGD-conjugated nanoparticles (400 μg mL−1) and excessive (2 × 10−6 M) free cRGD (i.e., the blocking assay or competitive binding assay) for 120 min. Thereafter, the cells were lifted using trypsin, washed, and fixed. Cellular uptake was analyzed based on Cy5 intensity using an Accuri C6 flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences, USA). A minimum of 10 000 cells were analyzed from each sample with fluorescence intensity shown on a four-decade log scale. For CLSM studies, OVCAR-3 cells (1.15 × 104 cells cm−2) were seeded onto an eight-chamber slide until the confluence of cells reached 80%. Cells were treated with either targeted (cRGD-conjugate) or nontargeted (cRGD-lacking) nanoparticles (400 μg mL−1), pure medium (i.e., the control group), or a combination of cRGD-conjugated nanoparticles and excessive (2 × 10−6 M) free cRGD (i.e., the competitive binding assay) for 2 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 1.5% formaldehyde. After fixing, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride (DAPI) was used to stain the cell nuclei. Cover slips were placed onto glass microscope slides and cellular uptake images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope equipped with Nikon A1R confocal diode lasers. For CLSM imaging, a UV-2E/C filter was used for the cell nuclei and a Y-2E/C filter was used for the nanoparticles.

2.12. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of free carboplatin and carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles was assessed using an 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. OVCAR-3 cells (2.4 × 104 cells cm−2) were seeded onto 96-well plates and grown overnight. Cells were treated with either free carboplatin (15 or 30 μg mL−1), carboplatin-complexed nontargeted nanoparticles, or carboplatin-complexed targeted nanoparticles at equivalent carboplatin concentrations (15 or 30 μg mL−1), or empty (drug-free) targeted or nontargeted nanoparticles (102 or 204 μg mL−1, and equivalent amounts of empty nanoparticles used for the carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles at 15 or 30 μg mL−1 of carboplatin) for 48 h. Thereafter, the cells were treated with fresh media containing 500 μg mL−1 MTT and incubated for another 4 h. After aspirating media containing MTT, 150 μL DMSO was added to dissolve the precipitates. The absorbance at 560 nm was measured by a GloMax-Multi+ Detection System (Promega, USA) with a reference absorbance at 730 nm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD

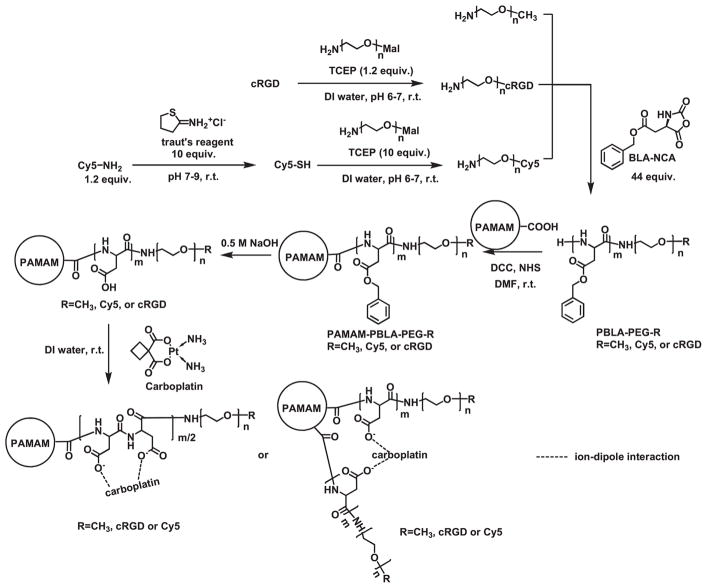

The PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD multi-arm star block copolymers conjugated with Cy5 and cRGD were prepared according to Scheme 2. First, PEG-NH2 with different terminal groups (i.e., NH2-PEG-Cy5 and NH2-PEG-cRGD) was synthesized via a maleimidethiol reaction. Small molecules (Cy5 dyes or cRGD targeting ligands) with active thiol groups were conjugated to PEG5000 with maleimide end groups at room temperature under a neutral pH. Secondly, PBLA-PEG-R (R = Cy5, cRGD, or OCH3) block copolymers were synthesized through ring-opening polymerization of BLA-NCA using PEG-NH2 as the macroinitiator. The degree of polymerization of PBLA was calculated to be 21 based on the relative intensity of the 1H NMR peak at 5.08 ppm, corresponding to the protons of the methylene unit of the benzyl group, and the peak at 3.66 ppm, corresponding to the protons on PEG segment.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis scheme of the hydrophilic PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD multi-arm star block copolymer conjugated with cRGD and Cy5.

The resulting linear PBLA-PEG-R (R=Cy5, cRGD, or OCH3) block copolymers were grafted onto a PAMAM-COOH core via a DCC/NHS catalyzed amidization reaction. The Mn and Mw of the PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-R (R = Cy5, cRGD, or OCH3), determined using a GPC equipped with triple detectors, were 324 364 and 388 716 Da, respectively. The number of arms was calculated to be 34 by Equation (1)

| (1) |

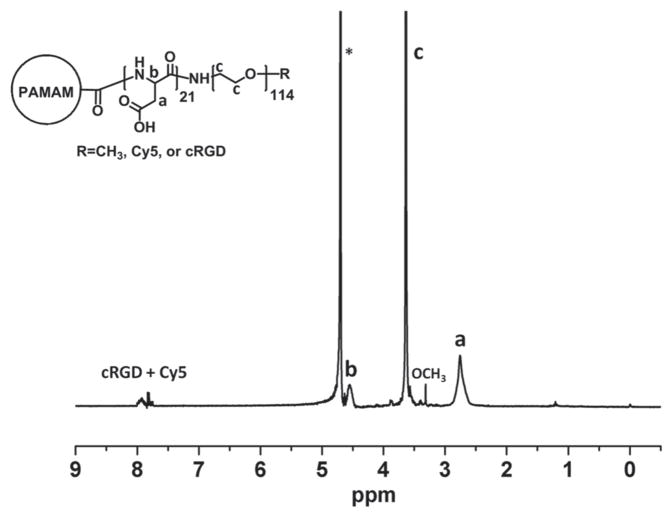

The PBLA segments present in the PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-R (R = Cy5, cRGD, or OCH3) copolymer were converted to poly(aspartic acid) through an alkaline hydrolysis process. It is worth noting that once the hydrophobic PBLA segments were converted to the hydrophilic poly(aspartic acid) segments, the multi-arm star amphiphilic block copolymer PAMAM-PBLA-PEG-R (R = Cy5, cRGD, or OCH3) copolymer became completely water soluble. The degree of conversion from PBLA to PAsp was monitored by NMR. The disappearance of the peaks located at 7.29 and 5.08 ppm confirmed the complete removal of the benzyl ester groups.

cRGD peptide and Cy5 were selectively conjugated to the distal ends of the PEG arms. The molar ratio of cRGD:Cy5:OCH3 conjugated onto the PEG arms was set to 2:1:7. cRGD was used as an active tumor-targeting ligand because it can efficiently bind to tumor marker αvβ3 integrin overexpressed by a number of cancers, including ovarian cancers, thereby enhancing the cellular uptake of the unimolecular nanoparticles. Cy5 dye was conjugated onto the surface of the nanoparticles to enable localization of the nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo via fluorescence imaging. Figure 1 shows the 1H NMR spectrum of the PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD multi-arm star block copolymer.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectrum of the hydrophilic PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD multi-arm star block copolymer conjugated with Cy5 and cRGD. The * represents the solvent residual peak.

3.2. Properties of Carboplatin-Complexed PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD Unimolecular Nanoparticles

Stable carboplatin-complexed unimolecular nanoparticles were formed in an aqueous solution by adding a PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD aqueous solution dropwise to a carboplatin aqueous solution. Carboplatin was complexed with the PAMAM-PAsp-PEG-OCH3/Cy5/cRGD nanoparticles through an intermolecular ion–dipole interaction—a force between the carboxylate groups of poly(aspartic acid) and carboplatin. Such ion–dipole interactions are pH-dependent: at a lower pH, the carboxylate groups are protonated thereby weakening the interaction between the nanoparticle and carboplatin, hence causing a pH-dependent release profile.[22,38]

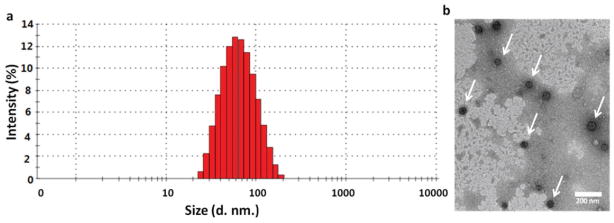

The size distribution of the unimolecular nanoparticles were investigated by DLS. Figure 2A shows the DLS histogram of the unimolecular nanoparticles. The hydrodynamic diameter of the unimolecular nanoparticles ranged from 22 to about 200 nm, with an average diameter of 58 nm, which is suitable for drug nanocarriers. The zeta-potentials of the empty unimolecular nanoparticles and carboplatin-complexed ones were −7.11 and −6.57 mV, respectively, indicating that the surfaces of the nanoparticles were slightly negatively charged.[47] The stability of the unimolecular nanoparticle was determined by measuring the average hydrodynamic diameter of the unimolecular nanoparticles as a function of time in OVCAR-3 cell culture media at 37 °C (Figure S1, Supporting Information). of the nanoparticle size changed only slightly from Day 0 (61 nm) to Day 5 (68 nm), indicating that the unimolecular nanoparticles exhibited excellent stability.

Figure 2.

A) DLS histogram and B) TEM image of the unimolecular nanoparticles. Scale bar: 200 nm.

The morphology of the dried unimolecular nanoparticles was studied by TEM as shown in Figure 2B. The dried nanoparticles had a diameter in the range of 40–60 nm, which was smaller than the hydrodynamic diameter measured by DLS. This can be attributed to the nanoparticles’ excellent water solubility leading to hydration and stretching of the hydrophilic polymer arms.

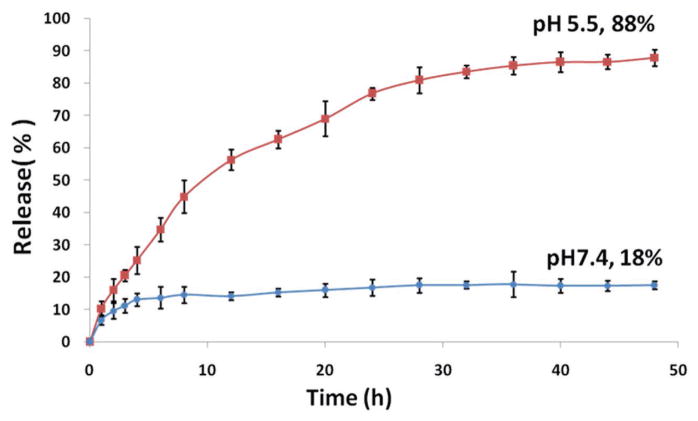

3.3. In Vitro Drug Release

The drug loading level of carboplatin-complexed unimolecular nanoparticles and the drug release behavior was determined by HPLC. Carboplatin-complexed unimolecular nanoparticles were dissolved in water for 48 h with its pH adjusted to 3 to allow complete dissociation of carboplatin. The drug loading content was measured using HPLC in triplicate and was calculated to be 14.7 ± 0.7 wt%. The carboplatin loading level was also analyzed by ICP-AES in quadruplicate and was calculated to be 16.4 ± 0.2 wt%, which was not statistically different from the drug loading content determined by HPLC (p > 0.05 according to a Student t-test). The drug release behavior of the carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles was investigated at 37 °C under physiological conditions (PBS buffer, pH 7.4) and an acidic environment mimicking the acidic endocytic compartments where the nanoparticles reside after being taken up by the cells via an endocytosis process (acetate buffer, pH 5.5). The drug release profile is shown in Figure 3. At pH 5.5, the carboplatin-complexed unimolecular nanoparticles showed a controlled release behavior, with 88% complexed carboplatin released after 40 h. In contrast, at pH 7.4, 18% carboplatin was released after 48 h; thereafter, the drug release curve nearly plateaued. This pH-dependent drug release behavior is highly desirable for drug delivery applications. During circulation in the blood stream (pH ~ 7.4) for in vivo application, the carboplatin encapsulated inside of the nanoparticle is relatively stable. Once the carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles are taken up by the cells via endocytosis, carboplatin can be released quickly under the acidic conditions in the endosomes/lysosomes.

Figure 3.

In vitro drug release profile of carboplatin-complexed unimolecular nanoparticles at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5.

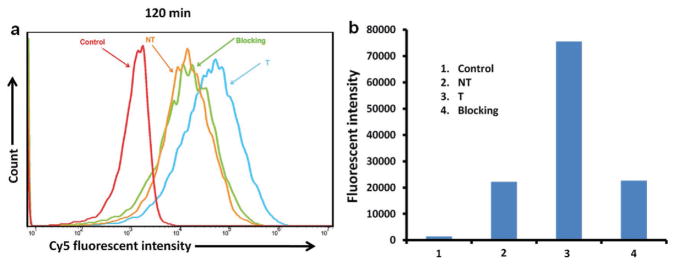

3.4. Cellular Uptake

The effects of cRGD-targeting ligands on the cellular uptake behaviors of the carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles by OVCAR-3 cells were studied using both flow cytometry and CLSM based on the fluorescence intensity of Cy5, which was conjugated onto the unimolecular nanoparticles. As shown in Figure 4, OVCAR-3 cells treated with pure medium were used as a negative control and showed only autofluorescence of the cells. The cellular uptake of cRGD-conjugated (i.e., targeted (T)) unimolecular nanoparticles was 3.4-fold higher than that of the cRGD-lacking (i.e., nontargeted (NT)) nanoparticles. Furthermore, the blocking assay indicates that in the presence of free cRGD, the cellular uptake of cRGD-conjugated (T) unimolecular nanoparticles was similar to that of the NT nanoparticles due to the competitive cRGD binding effect. These results demonstrated that cRGD-conjugation could effectively enhance the cellular uptake of the nanoparticles in cancer cells overexpressing αvβ3 integrin via receptor (i.e., αvβ3 integrin)-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 4.

Cellular uptake of the unimolecular nanoparticles in ovarian cancer cells. OVCAR-3 cells were treated with medium (Control), targeted (T), or nontargeted (NT) unimolecular nanoparticles, or a combination of targeted nanoparticles and free cRGD (i.e., the blocking assay) for 2 h. A) The fluorescence intensity of Cy5 as represented by flow cytograms. B) The relative fluorescence intensity analyzed by FlowJo 10.0.5 analysis software.

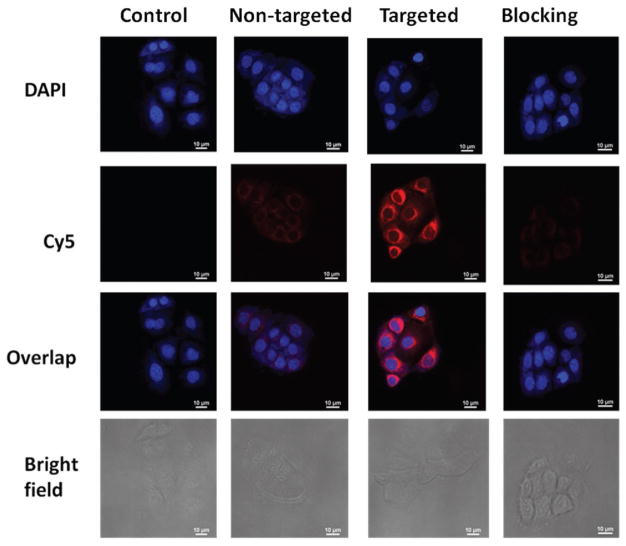

This finding was further confirmed by CLSM analysis. Figure 5 shows that the fluorescent intensity of Cy5 in OVCAR-3 cells treated with cRGD-conjugated nanoparticles was drastically higher than cells treated with either nontargeted nanoparticles or targeted nanoparticles in the presence of free cRGD (i.e., the blocking assay). In addition, it is clear that these carboplatin-complexed unimolecular nanoparticles were largely located in the cytosol of the ovarian cells.

Figure 5.

Cellular uptake of unimolecular nanoparticles. OVCAR-3 cells were treated with medium (Control), targeted (T), or nontargeted (NT) unimolecular nanoparticles, as well as a combination of targeted nanoparticles and free cRGD (i.e., the blocking assay) for 2 h.

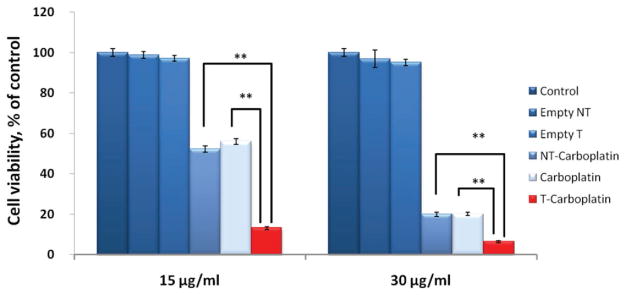

3.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

To determine the cytotoxicity of the unimolecular nanoparticles, an MTT assay was performed to analyze the cell viability of the OVCAR-3 cells treated with targeted and nontargeted unimolecular nanoparticles with or without carboplatin. OVCAR-3 cells treated with either free carboplatin or medium were used as controls. As shown in Figure 6, cells treated with empty targeted or nontargeted unimolecular nanoparticles, even at a relatively high concentration (about 200 μg mL−1), showed similar cell viabilities as the control group treated with medium, indicating that the empty targeted and nontargeted unimolecular nanoparticles were noncytotoxic. The cell viability of the cells treated with carboplatin-complexed targeted unimolecular nanoparticles was significantly lower than that of the cells treated with either free carboplatin or carboplatin-complexed nontargeted nanoparticles. This finding can be attributed to the poor cellular uptake of “free” carboplatin.[11,12] As aforementioned, cRGD-conjugation led to significantly higher cellular uptake of the carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles by ovarian cells via receptor (i.e., αvβ3 integrin)-mediated endocytosis.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxicity of OVCAR-3 cells treated with free carboplatin, carboplatin-complexed cRGD-conjugated (T-carboplatin), or cRGD-lacking (NT-carboplatin) unimolecular nanoparticles, and empty nanoparticles (Empty NT and Empty T) for 48 h at two carboplatin concentrations (15 and 30 μg mL−1). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

4. Conclusions

A unique water soluble unimolecular nanoparticle conjugated with tumor-targeting ligand, cRGD, and fluorescent dye, Cy5, was engineered as a stable platinum-based drug nanocarrier for targeted cancer therapy. The cRGD-conjugated unimolecular nanoparticles were made of individual hydrophilic multi-arm star block copolymers (PAMAM-PAsp-PEG). The unimolecular nanoparticles had a uniform spherical shape and an average hydrodynamic diameter of 58 nm. The carboplatin-complexed nanoparticles exhibited a desirable pH-sensitive drug release profile. The cRGD-conjugated nanoparticles also exhibited much higher cellular uptake (i.e., 3.4-fold) than nontargeted ones in OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells due to αvβ3 integrin-mediated endocytosis, thereby leading to a much higher cytotoxicity than both free carboplatin and carboplatin-complexed nontargeted nanoparticles. Thus, these cRGD-conjugated unimolecular nanoparticles are promising platinum-based drug nanocarriers that could enable targeted chemotherapy to treat a number of cancers overexpressing αvβ3 integrin, including ovarian cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the NIH (1K25CA166178 and R21CA196653 to S. Gong).

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the authors.

Contributor Information

Yuyuan Wang, Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery, Madison, WI 53715, USA.

Liwei Wang, Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Guojun Chen, Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery, Madison, WI 53715, USA.

Shaoqin Gong, Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Wisconsin Institutes for Discovery, Madison, WI 53715, USA. Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

References

- 1.Zhang D, Holmes WF, Wu S, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. J Cell Physiol. 2000;185:1. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200010)185:1<1::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Ovary Cancer. NCI; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC, Ledermann JA. Lancet. 2014;384:1376. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang S, Balch C, Chan MW, Lai HC, Matei D, Schilder JM, Yan PS, Huang THM, Nephew KP. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4311. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go RS, Adjei AA. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg B. Interdiscip Sci Rev. 1978;3:134. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheate NJ, Walker S, Craig GE, Oun R. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:8113. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00292e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannigan EV, Green S, Alberts DS, O’Toole R, Surwit E. Oncology. 1993;50:2. doi: 10.1159/000227253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zutphen Sv, Reedijk J. Coord Chem Rev. 2005;249:2845. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Timmer-Bosscha H, Mulder NH, de Vries EG. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:227. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yonezawa A, Masuda S, Yokoo S, Katsura T, Inui K-i. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:879. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Los G, Verdegaal E, Noteborn HPJM, Ruevekamp M, deGraeff A, Meesters EW, Ten Bokkel Huinink D, McVie JG. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:357. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90723-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kartalou M, Essigmann JM. Mutat Res, Fundam Mol Mech Mutagen. 2001;478:23. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart DJ. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63:12. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langer R. Nature. 1998;392:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis ME, Chen Z, Shin DM. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:771. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne JD, Betancourt T, Brannon-Peppas L. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2008;60:1615. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brannon-Peppas L, Blanchette JO. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2004;56:1649. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganta S, Devalapally H, Shahiwala A, Amiji M. J Controlled Release. 2008;126:187. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emilienne Soma C, Dubernet C, Bentolila D, Benita S, Couvreur P. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Wang YC, Dou S, Xiong MH, Sun TM, Wang J. ACS Nano. 2011;5:3679. doi: 10.1021/nn200007z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu S, Chow GM. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:2781. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nishiyama N, Okazaki S, Cabral H, Miyamoto M, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y, Nishio K, Matsumura Y, Kataoka K. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Q, Qi R, Cai J, Kang X, Sun S, Xiao H, Jing X, Li W, Wang Z. RSC Adv. 2015;5:83343. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishiyama N, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y, Kataoka K. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1035. doi: 10.1023/a:1010908916184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirbin SJ, Ladewig K, Fu Q, Klimak M, Zhang X, Duan W, Qiao GG. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:2463. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu Q, Xu J, Ladewig K, Henderson T, Qiao G. Polym Chem. 2015;6:35. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabaharan M, Grailer JJ, Pilla S, Steeber DA, Gong S. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3009. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prabaharan M, Grailer JJ, Pilla S, Steeber DA, Gong S. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5757. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen G, Jaskula-Sztul R, Harrison A, Dammalapati A, Xu W, Cheng Y, Chen H, Gong S. Biomaterials. 2016;97:22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Grailer JJ, Pilla S, Steeber DA, Gong S. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:496. doi: 10.1021/bc900422j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen G, Wang L, Cordie T, Vokoun C, Eliceiri KW, Gong S. Biomaterials. 2015;47:41. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaskula-Sztul R, Xu W, Chen G, Harrison A, Dammalapati A, Nair R, Cheng Y, Gong S, Chen H. Biomaterials. 2016;91:1. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brinkman AM, Chen G, Wang Y, Hedman CJ, Sherer NM, Havighurst TC, Gong S, Xu W. Biomaterials. 2016;101:20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo J, Hong H, Chen G, Shi S, Nayak TR, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W, Gong S. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:21769. doi: 10.1021/am5002585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu W, Burke JF, Pilla S, Chen H, Jaskula-Sztul R, Gong S. Nanoscale. 2013;5:9924. doi: 10.1039/c3nr03102k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu W, Siddiqui IA, Nihal M, Pilla S, Rosenthal K, Mukhtar H, Gong S. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5244. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim YS, Song R, Chung HC, Jun MJ, Sohn YS. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98:98. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai W, Niu G, Chen X. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2943. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai W, Chen X. Anti-Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2006;6:407. doi: 10.2174/187152006778226530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdollahi A, Griggs DW, Zieher H, Roth A, Lipson KE, Saffrich R, Gröne HJ, Hallahan DE, Reisfeld RA, Debus J. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6270. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang X, Hong H, Grailer JJ, Rowland IJ, Javadi A, Hurley SA, Xiao Y, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Nickles RJ, Cai W, Steeber DA, Gong S. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4151. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mittal A, Chitkara D, Kumar N. J Chromatogr B. 2007;855:211. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torgov VG, Korda TM, Demidova MG, Gus’kova EA, Bukhbinder GL. J Anal At Spectrom. 2009;24:1551. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dominici C, Alimonti A, Caroli S, Petrucci F, Castello MA. Clin Chim Acta. 1986;158:207. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(86)90284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Waal WAJ, Maessen FJMJ, Kraak JC. J Chromatogr A. 1987;407:253. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)92623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clogston JD, Patri AK. In: Characterization of Nanoparticles Intended for Drug Delivery. McNeil SE, editor. Humana Press; New York: 2011. pp. 63–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.