INTRODUCTION

Acute cholecystitis is a common medical condition traditionally managed surgically. However, early surgical intervention is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially in patients with multiple comorbidities, advanced age and those with severe cholecystitis based on Tokyo guidelines.[1,2] In cases of increased surgical risk, urgent percutaneous gallbladder drainage (GBD) can be used to temporize the patient's condition until cholecystectomy can safely be performed as definitive therapy.[3] Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an effective therapy for gallbladder decompression, and its use in the Medicare population has increased nearly tenfold from 1994 to 2009.[4,5]

The utility of percutaneous cholecystostomy is counterbalanced by several factors including patient discomfort, and need to manage an external tube as well as associated complications including catheter dislodgement, cellulitis, fistula formation, and infection. For this reason, it best utilized as a temporary solution.[6] While the intent of percutaneous cholecystostomy tube, placement is usually a bridge to cholecystectomy, or for potential removal after clinical improvement, the tube may become permanent when operative risk is excessive due to underlying medical comorbidities and/or factors are present in which there is high-risk of recurrent cholecystitis after drain removal. In these cases, long-term percutaneous drain placement can result in significant pain, inconvenience, and cosmetic disfigurement resulting in a decrease in quality of life.[7]

There are two main endoscopic approaches for the management of gallbladder disease: Endoscopic transpapillary GBD (ETGBD) and EUS-guided transmural GBD (EUS-GBD). When performed by skilled therapeutic endoscopists, both methods can be achieved with technical success rates above 90%.[8] Endoscopic procedures may be a plausible alternative when percutaneous drainage is contraindicated, such as in patients with ascites, coagulopathy or an anatomically inaccessible gallbladder.[9] ETBGD was first described in 1990 with good technical and clinical success rates, however, it can be technically challenging and prohibitively difficult due to tortuosity, stricture, calculus, or malignant cystic duct obstruction.[10] ERCP pancreatitis is a well-known and occasionally serious complication of ETGBD.[11] In addition, the relatively small caliber biliary stents used for transpapillary drainage may become occluded leading to recurrent cholecystitis and need for reintervention.

EUS-GBD, first described in 2007,[12] takes advantage of the anatomic proximity of the gallbladder and the gastrointestinal tract and the visibility of the gallbladder on endosonography. This method bypasses some of the anatomic constraints inherent to ETGBD, the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis, and is associated with significantly less postprocedural pain than percutaneous GBD.[13] While EUS-GBD was initially performed with standard plastic biliary prostheses, the recent availability of self-expandable lumen apposing metal stents (LAMS) has added additional endoscopic options for the management of gallbladder disease. Placement of a LAMS into a gallbladder that has been decompressed with percutaneous cholecystostomy is possible and allows internalization of a percutaneous drain.[14] In this review, we will discuss the use of EUS-GBD as a method of internalizing GBD after percutaneous drain placement, including technical considerations, and future directions of the procedure.

ANATOMIC SITE SELECTION FOR EUS-GALLBLADDER DRAINAGE

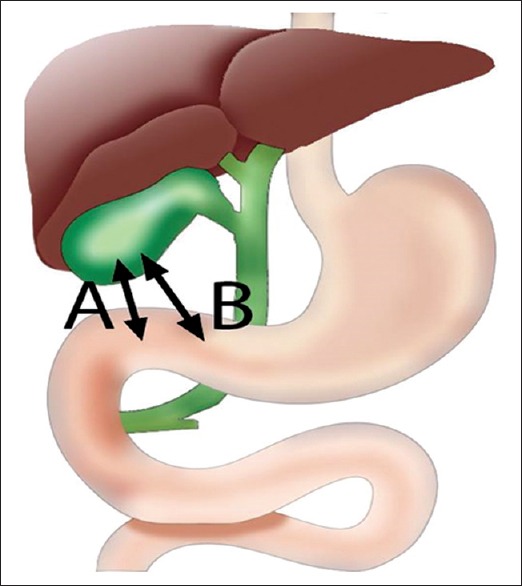

There are two approaches to gallbladder puncture in EUS-GBD: transgastric and transduodenal [Figure 1].[15] Using a curvilinear array echoendoscope in the long position (pushing scope position), the gallbladder is visualized from the duodenal bulb or the antrum of the stomach. The approach will need to be revised if a patient has surgically altered anatomy – such as following gastrojejunostomy, where the gallbladder may be visualized in the second jejunum or following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Figure 1.

Initial puncture site in EUS-guided gallbladder drainage: (A) Duodenal bulb (B) gastric antrum

The health and viability of the gastric mucosa should be considered when selecting an initial puncture site, as interposed gastric or pancreatic cancer may increase the difficulty of the procedure and lead to technical failure and poor clinical outcomes. Malignant tissue is often hypervascular which can increase the risk of procedure-related bleeding. If gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is present, the passage of the echoendoscope into the duodenum may not be possible. In addition, patients with GOO may have retained stomach contents which may increase the procedural difficulty of EUS-GBD, and the risk of serious adverse events and the underlying GOO may need to be addressed endoscopically as well.

LUMEN-APPOSING METAL STENT PLACEMENT IN EUS-GALLBLADDER DRAINAGE

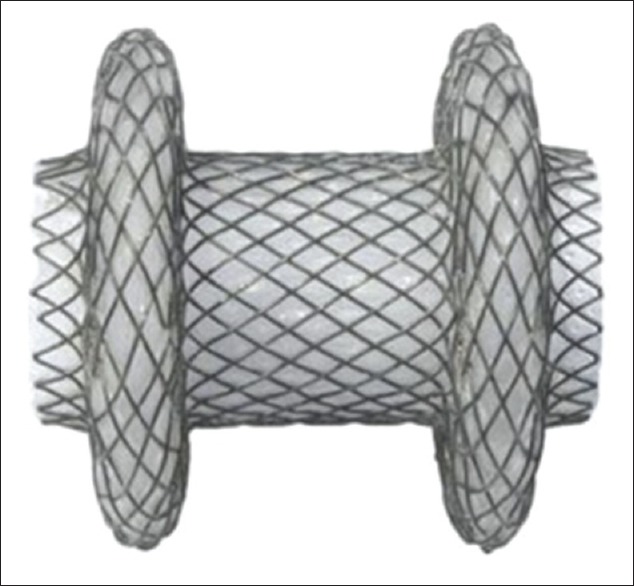

The first LAMS used for EUS-GBD was a 15 mm diameter, 10 mm long fully covered stent (AXIOS™, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). The development of the AXIOS-EC™, an electrocautery-enabled access catheter enhanced AXIOS Stent (commonly referred to as “Hot Axios”), has the potential to eliminate the need for initial needle puncture and guidewire placement as well as the need for tract dilation, and as a result, may avoid loss of guidewire access. The AXIOS-EC™ consists of a fully covered metal stent with bilateral anchoring flanges [Figure 2]. Other LAMS are available outside the USA including the SPAXUS™ stent and Nagi™ stents (TaeWooong Medical, Seoul, South Korea). LAMS placement adheres the gallbladder wall against either the duodenal or gastric wall to maintain attachment of the two structures. If the distance to the gallbladder from the gastrointestinal lumen is longer than 1 cm, conventional fully covered biliary self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) can be used. At present, the Axios is available in diameters of 10 and 15 mm [Figure 2]. It is unclear if there is a need for a diameter >10 mm, and it is possible that larger diameters facilitate entry of food into the stent and represent a potential source of stent occlusion. Indeed it is believed that gastric placement also predisposes to food entry and occlusion (personal communication, Anthony Teoh).

Figure 2.

AXIOS stent (Boston scientific)

EUS-GALLBLADDER DRAINAGE PROCEDURE DESCRIPTION

The linear echoendoscope is advanced transorally to either the stomach or duodenum and the gallbladder is visualized endosonographically. It is important to note that in cases of EUS-GBD for drain internalization, the gallbladder is often decompressed at the time of the procedure. Injection of saline with or without contrast can distend the gallbladder to increase the target, though if the cystic duct is patent this benefit may be short lasting. A 19-gauge needle is inserted either transduodenally or transgastrically into the gallbladder under EUS visualization, followed by injection under fluoroscopic guidance to confirm positioning although this is not always necessary based on endoscopist comfort level. A guidewire, typically 450 cm long, 0.025–0.035 inch, is inserted through the needle and allowed to coil in the gallbladder.

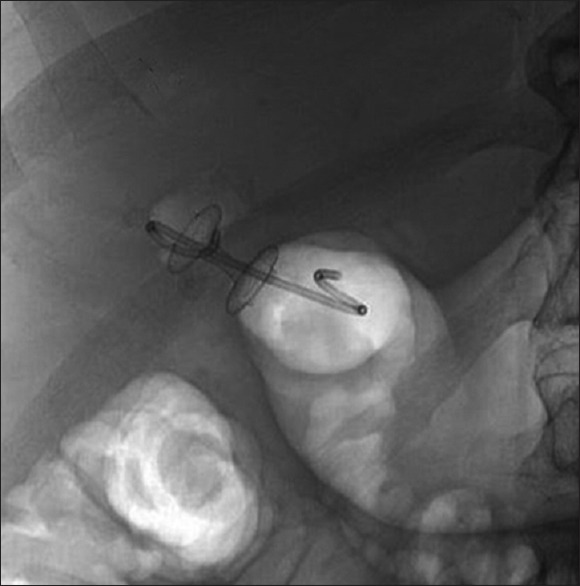

The next steps of the procedure vary based on the type of SEMS available. In the case of stents without an available electrocautery delivery system, dilating catheters and/or electrocautery devices followed by balloon dilation up to 6 mm are advanced through the transmural fistula for dilation. The SEMS is advanced over the guidewire and through the puncture site into the gallbladder. The distal stent flange is first deployed and abutted against the gallbladder wall under EUS guidance, followed by proximal flange deployment in the duodenum or stomach, creating a cholecystoduodenostomy or cholecystogastrostomy, respectively. If the AXIOS-EC™ stent is employed for EUS-GBD, the electrocautery enhanced tip is directly advanced into the gallbladder using pure cutting current either “freehand” or over a guidewire placed after needle puncture. We almost always place a single 7 Fr double pigtail plastic stent through any SEMS to prevent occlusion by food impaction, stones, or luminal abutment as the gallbladder collapses [Figure 3]. In the event, the proximal LAMS flange is mis-deployed within the extraluminal space; it may be possible to salvage the fistulous tract by placing a biliary SEMS within the LAMS lumen. The absence of a peritoneal leak and the final position of the stent may be confirmed by injection of water-soluble contrast.

Figure 3.

Placement of the lumen apposing metal stents creating a cholecystoduodenostomy. A 7F catheter, 4-cm double pigtail plastic stent was placed within the lumen apposing metal stents to serve as an anchor

There is not an agreed on timeframe for percutaneous catheter removal although immediate removal of a mature percutaneous tract (3–4 weeks after initial placement) following endoscopic drainage has been described without significant adverse events. The timing of percutaneous catheter removal should be individualized and dictated by perceived treatment success (i.e., good positioning), multidisciplinary input, and duration of external catheter placement.

TECHNICAL CHALLENGES

In most cases of primary EUS-GBD for the treatment of acute cholecystitis, the gallbladder is distended and serves as an easily visualized target, allowing for straightforward access and LAMS placement. In contrast, secondary EUS-GBD is technically challenging due to reduced endosonographic visualization, difficulty coiling the guidewire within a smaller gallbladder, transmural tract creation and LAMS deployment. In addition, chronic cholecystitis may lead to a thick-walled, fibrotic gallbladder which makes it difficult to pass a dilating balloon and/or electrocautery device without causing a separation between the gallbladder and gastrointestinal tract. The limited mechanical advantage inherent in secondary EUS-GBD may be overcome by grasping the transmurally placed guidewire from within the gallbladder using forceps passed through the percutaneous tract, either under fluoroscopic visualization or through a cholangioscope. This additional traction on both ends of the guidewire markedly improves the mechanical advantage, and eliminates the possibility of guidewire loss. These technical constraints in secondary EUS-GBD may be decreased with electrocautery-enhanced LAMS as the electrocautery tip greatly reduces the friction of the enteric and gallbladder walls, reducing the need for traction as the force of insertion is applied.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS OF GALLBLADDER DRAIN INTERNALIZATION

EUS-guided conversion of percutaneous GBD to internal drainage through cholecystoenterostomy or cholecystogastrostomy using a LAMS is technically feasible, though is generally more challenging than primary EUS-guided transmural GBD. Further study of endoscopic drainage techniques and device modifications are essential to resolving the technical challenges encountered in this patient population. In addition, studies on patient-reported outcomes following the procedure and the effect of drain internalization on quality of life have not yet been conducted.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Baron is a consultant and speaker for Boston Scientific and Olympus. Dr. James is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32DK07634).

REFERENCES

- 1.Glenn F. Cholecystostomy in the high risk patient with biliary tract disease. Ann Surg. 1977;185:185–91. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197702000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Ko CY, et al. A current profile and assessment of North American cholecystectomy: Results from the American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:176–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman M, Nudelman IL, Fuko Z, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy: Effective treatment of acute cholecystitis in high risk patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:331–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopra S, Dodd GD, 3rd, Mumbower AL, et al. Treatment of acute cholecystitis in non-critically ill patients at high surgical risk: Comparison of clinical outcomes after gallbladder aspiration and after percutaneous cholecystostomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1025–31. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.4.1761025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duszak R, Jr, Behrman SW. National trends in percutaneous cholecystostomy between 1994 and 2009: Perspectives from medicare provider claims. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9:474–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatzidakis AA, Prassopoulos P, Petinarakis I, et al. Acute cholecystitis in high-risk patients: Percutaneous cholecystostomy vs. conservative treatment. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:1778–84. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamata K, Kitano M, Komaki T, et al. Transgastric EUS (EUS)-guided gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41(Suppl 2):E315–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Widmer J, Alvarez P, Sharaiha RZ, et al. Endoscopic gallbladder drainage for acute cholecystitis. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:411–20. doi: 10.5946/ce.2015.48.5.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis in whom percutaneous transhepatic approach is contraindicated or anatomically impossible (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:455–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pannala R, Petersen BT, Gostout CJ, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage: 10-year single center experience. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2008;54:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feretis CB, Manouras AJ, Apostolidis NS, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary drainage of gallbladder empyema. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:523–5. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(90)71134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baron TH, Topazian MD. Endoscopic transduodenal drainage of the gallbladder: Implications for endoluminal treatment of gallbladder disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:735–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang JW, Lee SS, Song TJ, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural and percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage are comparable for acute cholecystitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:805–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law R, Grimm IS, Stavas JM, et al. Conversion of percutaneous cholecystostomy to internal transmural gallbladder drainage using an endoscopic ultrasound-guided, lumen-apposing metal stent. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:476–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoi T, Itokawa F, Kurihara T. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gallbladder drainage: Actual technical presentations and review of the literature (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:282–6. doi: 10.1007/s00534-010-0310-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]